Abstract

Importance

Accumulating evidence indicates that common carcinogenic pathways may underlie digestive system cancers. Physical activity may influence these pathways, yet no previous study has evaluated the role of physical activity in overall digestive system cancer risk.

Objective

To examine the association between physical activity and digestive system cancer risk, accounting for amount, type (aerobic versus resistance), and intensity of physical activity.

Design

A prospective cohort study followed from 1986 to 2012.

Setting

Male health professionals living in the general community in the US

Participants

Eligible participants were 40 years or older, were free of cancer, and reported physical activity. Out of 51,529 individuals, 43,479 were followed-up, with follow-up rates exceeding 90% in each 2-year cycle.

Exposures

The amount of total physical activity expressed in metabolic equivalent of task [MET]-hours/week

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incident cancer of the digestive system encompassing the digestive tract (mouth, throat, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colorectum) and digestive accessory organs (pancreas, gallbladder, and liver).

Results

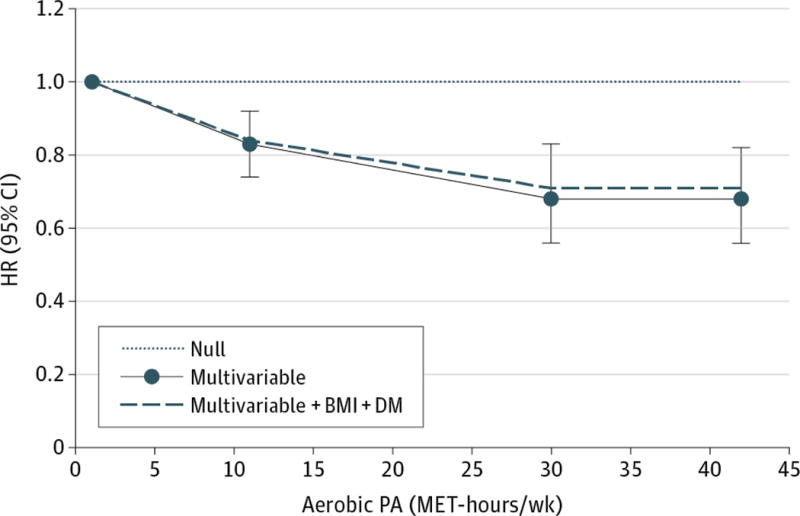

Over 686,924 person-years, we documented 1,370 incident digestive system cancers. Higher levels of physical activity were associated with lower digestive system cancer risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74 for 63+ versus ≤8.9 MET-hours/week; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-0.93; P for trend, .003). The inverse association was more evident with digestive tract cancers (HR, 0.66 for 63+ versus ≤8.9 MET-hours/week; 95% CI, 0.51-0.87) than with digestive accessary organ cancers. Aerobic exercise was particularly beneficial against digestive system cancers, with the optimal benefit observed at approximately 30 MET-hours/week (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56-0.83; Pnon-linearity, 0.02). Moreover, as long as the same level of MET-hour score was achieved from aerobic exercise, the magnitude of risk reduction was similar regardless of intensity of aerobic exercise.

Conclusion and Relevance

Physical activity, as indicated by MET-hours/week, was inversely associated with the risk of digestive system cancers, particularly digestive tract cancers, in men. The optimal benefit was observed through aerobic exercise of any intensity at the equivalent of energy expenditure of approximately 10 hours/week of walking at average pace. Future studies are warranted to confirm our findings and to translate them into clinical and public health recommendation.

Introduction

Digestive system cancers (DSC) include cancers of the digestive tract (mouth, throat, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colorectum) and cancers of digestive accessory organs (pancreas, gallbladder, liver). While individual DSC are etiologically heterogeneous, accumulating evidence suggests potential presence of common carcinogenic pathways underlying DSC. The most substantiated is the pro-inflammatory pathway mediated by cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 enzyme. For instance, a functional polymorphism in COX-2 gene was associated with an increased risk of DSC, particularly.1 Furthermore, observational studies and randomized controlled trials consistently observed that aspirin, which inhibits COX-2, was notably protective against DSC.2,3 Thus, factors that affect the COX-2 pathway may modify the risk of overall DSC. One potential candidate is physical activity (PA), which is shown to reduce the COX-2 pro-inflammatory pathway.4 Additionally, the benefit of PA on colorectal cancer survival was confined to COX-2 positive cancers.5

Currently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) advises that adults engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate PA, or 75 minutes of vigorous PA, or an equivalent combination per week for cancer prevention.6 However, this guideline was not specifically designed for DSC and potential interactions between domains of PA (overall energy expenditure, type, and intensity) remain to be investigated to help refine the recommendations. Considering that PA is a modifiable lifestyle factor and that DSC accounted for an estimated 18% of cancer incidence and 26% of cancer deaths excluding non-melanoma skin cancer in the U.S. in 2012,7 investigating the relationship between PA and DSC risk accounting for diverse domains of PA has an important public health implication.

Methods

Study Population

The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study is an ongoing cohort study that began in 1986, enrolling 51,529 U.S. male health professionals aged 40-75 years.8 Participants completed a baseline questionnaire and biennial follow-up questionnaires, with follow-up rates exceeding 90% in each 2-year cycle. The study was approved by the human subjects committees at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and all participants provided written informed consent.

For this analysis, the baseline was defined as 1986 when PA was first assessed. At baseline, we excluded men having a prior cancer diagnosis(No=2,000) or missing data on PA(No=216), body mass index (BMI)(No=2,090), or dietary information(No=1,595). To minimize potential bias from reverse causation, we also excluded men reporting difficulty with walking or stair climbing at any point during the follow-up since 1988(No=2,149), the first year when this information was collected. The final analytic cohort included 43,479 men.

Assessment of PA

In 1986 and every two years thereafter, participants reported average time spent per week in the previous year at each of the following nine PA: walking, jogging, running, bicycling including stationary machine, lap swimming, tennis, squash/racket ball, calisthenics/rowing, and outdoor work. Participants also reported their usual walking pace as easy, average, brisk, or very brisk and number of flights of stairs climbed per day. Questions on weight lifting were added in 1990 and asked every two years thereafter. Each PA was asked in 10 response categories ranging from none to 11-20 hours/week.

For each PA, weekly energy expenditure was estimated by multiplying the typical intensity expressed in Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET, the ratio of metabolic rate during the activity to metabolic rate at rest)9 by the reported hours spent per week. For walking, we assigned 2, 3, 4, and 4.5 MET to casual, normal, brisk, and very brisk pace, respectively and assumed 3 MET for pace missing. Across PA, the weekly MET-hour scores were summed to derive our primary exposure (total weekly energy expenditure attributable to overall discretionary PA in unit of MET-hours/week).

By type of PA, aerobic PA included walking at least at average pace, jogging, running, bicycling, swimming, tennis, squash/racket ball, calisthenics/rowing, and stair climbing; resistance PA was marked by weight lifting.

The questionnaire was validated against four single-week activity diaries administered across four different seasons (correlation=0.65) and against resting heart rate (correlation=–0.45); had 0.41 for the test-retest correlation in a 2 year span.10

Assessment of covariates

A validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires listing over 130 food items11,12 was administered every four years to assess dietary intake over the past year. Biennial questionnaires collected information on potential cancer risk factors including age, race, smoking status, history of diabetes mellitus (DM), family history of cancer, screening physical examination, endoscopy, aspirin use, and multivitamin use. BMI was calculated using self-reported height and weight. Missing values were handled by carrying forward information from the previous cycle or using missing category, but the proportion of missing was negligible for most covariates(<1%).

Ascertainment of incident cancer

Our primary endpoint was incident DSC as defined in the introduction, which was reported through biennial follow-up questionnaires through 2012. Physicians blinded to the participants’ exposure status reviewed medical records to confirm self-reported cancer diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated with Cox proportional hazards models using age as the underlying time scale.13 Person-time of follow-up was accrued from the return date of the baseline questionnaire (1990 questionnaire for analyses involving weight lifting) until the date of cancer diagnosis, death from any cause, or analysis end (2012) as determined by availability of data ready for analysis, whichever came first. To reduce potential bias from reverse causation, we added a 2-year latency period between PA and cancer incidence. Potential confounders in multivariable analyses were determined a priori from established and suspected risk factors for DSC. To better represent the long-term average and to minimize random within-person variation, values PA and potential confounders were updated using cumulative average whenever new information was obtained from the follow-up questionnaires.

For categorical analysis of total PA, we created five categories (≤8.9, 9-20.9, 21-41.9, 42-62.9, and 63+ MET-hours/week). The cut-offs were chosen in multiples of 3 MET-hours/week (equivalent to 1 hour/week of walking at average pace) so that each category represents PA in terms of the most popular and safest type of exercise in a realistic and achievable range (≤0.3, 0.4-0.9, 1-1.9, 2-2.9, and 3+ hours/day of walking at average pace), which facilitates translation of our findings into public health recommendations. A potential linear trend was examined by assigning each exposure category the median value and by treating this variable as a continuous variable. Because obesity and DM may be potential intermediates,14-17 our primary multivariable analysis did not control for them. Yet, to estimate the degree to which the association of PA with cancer incidence was explained by obesity and DM, we ran another multivariable model additionally including these variables. Potential heterogeneity in the relationship by digestive tract cancers versus digestive accessory organ cancers was checked using competing Cox proportional hazards model with a data augmentation method.18 As sensitivity analyses to examine potential influence of residual confounding, we ran the primary multivariable analyses across strata of potential confounders; after excluding health conscious individuals as indicated by having family history of cancer or undergoing screening physical examination. There was no evidence of departure from the proportional hazard assumption, given P>0.05 from the Wald test performed for an additionally added interaction term between continuous PA and continuous age.

Given the same amount of energy expenditure from PA, the effect of PA on DSC may vary by PA type (aerobic versus resistance). Thus, we examined the joint association of amount and type, using weekly MET-hour scores from aerobic PA or weight lifting and participation in weight lifting.

For aerobic PA, the dominant type of PA in our study population, we ran more detailed analyses. First, the dose-response relationship was examined with restricted cubic splines.19 To reduce the influence of extreme values, we excluded individuals above the 95th percentiles of aerobic PA level. Three knots were fixed at the 5th, 50th, 95th percentiles of the remaining aerobic PA level and reference was set to 1 MET-hours/week. The potential for non-linearity was evaluated using the likelihood ratio test comparing the fit of two nested multivariable models: linear and non-linear models. Second, to explore if achieving a level of energy expenditure through intense exercise was more beneficial, we examined the joint association of amount and intensity of aerobic PA. In this analysis, activities included were restricted to walking at least at average pace, jogging, and running, which represent similar styles of aerobic PA with different intensity. Amount was estimated by weekly MET-hour scores from the three PA; intensity was estimated by average MET of the three PA weighted by hours spent for each PA. We dichotomized the intensity score at 4.5, with ≤4.5 representing mostly walking inclusive of all walking paces and >4.5 representing more intense aerobic PA.

For all the joint analyses, <3 relevant MET-hour score irrespective of type or intensity of PA was set as the reference, as it represents a negligible level of PA. All the statistical tests were two-sided and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The 43,479 men contributed 686,924 person-years from 1986 to 2012 and 1,370 incident cases of DSC (1,070 digestive tract cancers, 300 digestive accessory organ cancers) from 1988 to 2012. Across all levels of total PA, men accumulated total MET-hours/week primarily through aerobic PA. Yet, physically more active men engaged in more intense aerobic PA and more weight lifting. They also tended to be older, leaner, never smokers, and non-diabetics; to have a family history of cancer, to undergo physical examinations for screening, to take aspirin and multivitamins, and to consume higher levels of total calories, alcohol, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age-standardized Characteristics of Person-years by Level of Total Physical Activity in HPFS over 1986-2012

| Total Physical Activity (MET-hours/week)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristicsa | ≤ 8.9 | 9-20.9 | 21-41.9 | 42-62.9 | 63+ |

| No. of person-years | 153,020 | 172,674 | 196,381 | 96,922 | 67,927 |

| Selected physical activity, mean (SD), MET-hours/week | |||||

| Total physical activity | 4.2(2.7) | 14.8(3.5) | 30.4(5.9) | 51.3(6.0) | 88.5(33.1) |

| Aerobic physical activity | 3.4(2.5) | 12.0(4.5) | 24.5(8.4) | 41.3(13.1) | 72.7(37.7) |

| Weight lifting | 0.2(0.7) | 0.8(2.1) | 1.7(3.5) | 2.7(4.7) | 4.3(7.4) |

| Walking at average/brisk/very brisk pace | 2.2(2.1) | 6.3(4.7) | 10.8(8.5) | 16.2(13.9) | 20.6(16.9) |

| Jogging | 0.2(0.8) | 1.0(2.4) | 2.0(4.1) | 3.1(6.1) | 5.4(11.5) |

| Running | 0.1(0.5) | 0.9(2.8) | 3.5(7.1) | 7.5(12.8) | 19.0(28.8) |

| Average MET score, b mean (SD), MET | 3.1(1.6) | 4.1(1.7) | 4.6(2.0) | 5.0(2.2) | 5.6(2.4) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 60.0(10.0) | 61.6(9.9) | 62.6(10.0) | 63.3(10.1) | 63.1(10.2) |

| Caucasian, % | 93 | 95 | 95 | 96 | 95 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.2(3.7) | 25.8(3.2) | 25.4(2.9) | 25.3(3.0) | 25.0(3.0) |

| Smoking status, % | |||||

| Never smokers | 45 | 47 | 48 | 50 | 51 |

| Past smokers | 42 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 40 |

| Current smokers | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| History of diabetes, % | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Family history of cancer,c % | 33 | 36 | 39 | 38 | 38 |

| Physical examination for screening purpose, % | 42 | 53 | 57 | 57 | 56 |

| Current aspirin use, % | 41 | 51 | 56 | 55 | 55 |

| Current multivitamin use, % | 34 | 44 | 48 | 49 | 49 |

| Dietary intake, mean (SD) | |||||

| Total calories, kcal/day | 1897(565) | 1929(537) | 1984(541) | 2044(558) | 2121(579) |

| Alcohol, g/day | 10.1(15.0) | 10.6(13.4) | 11.1(13.1) | 11.7(13.4) | 11.5(13.3) |

| Red/processed meat, servings/day | 1.2(0.8) | 1.1(0.7) | 1.0(0.7) | 1.0(0.7) | 1.0(0.8) |

| Whole grains, servings/day | 1.3(1.1) | 1.4(1.1) | 1.5(1.1) | 1.6(1.2) | 1.8(1.3) |

| Fruit, servings/day | 2.1(1.4) | 2.3(1.4) | 2.5(1.4) | 2.8(1.5) | 3.1(1.7) |

| Vegetables, servings/day | 2.8(1.5) | 3.1(1.5) | 3.3(1.5) | 3.5(1.6) | 3.8(1.8) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task

Note: Smoking status does not sum up to 100% due to missing category.

All values, except age, are standardized to the age distribution of the study population during follow-up.

Weighted average of MET values of walking (at normal, brisk, or very brisk pace), jogging, and running using weekly hours spent for each activity as the weight.

Family history of cancer was defined based on colorectal, pancreatic, lung, prostate, breast, and skin cancers among father, mother, and siblings.

Total PA was inversely associated with DSC risk, which was largely driven by digestive tract cancers (Table 2). The age-adjusted and multivariable results were similar, with multivariable HR comparing 63+ versus ≤8.9 MET-hours/week being 0.74 (95% CI, 0.59-0.93; Ptrend, .003) for DSC and 0.66 (95% CI, 0.51-0.87; Ptrend, .003) for digestive tract cancers. The corresponding results for digestive accessory organ cancers were 1.02 (95% CI, 0.66, 1.58; Ptrend, .46), but heterogeneity in the linear association across digestive tract cancers and digestive accessory organ cancers was not statistically significant (Pheterogeneity, .47). The results were not altered appreciably after additional adjustments for BMI and DM. Within digestive tract cancers, a strong association was observed for cancers of the upper digestive tract from mouth to small intestine (HR for 63+ versus ≤8.9 MET-hours/week, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30-0.85; Ptrend, .03) and persisted independent of BMI and DM. An inverse relationship was consistently observed for individual cancers of the digestive tract (see eTable 1 in the Supplement), in stratified analyses by potential confounders (see eFigure 1 in the Supplement), and after excluding those with family history of cancer or screening physical examination (see eTable 2 in the Supplement), although its statistical significance was sensitive to case numbers in each analysis. For colorectal cancer, statistical significance of an inverse trend was lost when BMI was additionally adjusted for, but further adjustment for DM had little influence on the results.

Table 2.

HR and 95% CI of Total and Site-specific Digestive System Cancers by Total Physical Activity

| Total Physical Activity (MET-hours/week)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites of Digestive System Cancers | ≤ 8.9 | 9-20.9 | 21-41.9 | 42-62.9 | 63+ | Plinear trend |

|

Total Digestive System

|

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 343 | 361 | 373 | 182 | 111 | 1,370 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 0.90(0.78,1.05) | 0.80(0.69,0.94) | 0.77(0.64,0.93) | 0.70(0.56,0.87) | <.001 |

| Multivariablea | 1(reference) | 0.94(0.80,1.09) | 0.85(0.73,0.99) | 0.81(0.67,0.98) | 0.74(0.59,0.93) | .003 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 0.95(0.82,1.11) | 0.87(0.74,1.01) | 0.84(0.69,1.01) | 0.77(0.61,0.97) | .01 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 1(reference) | 0.95(0.82,1.11) | 0.87(0.75,1.02) | 0.85(0.70,1.02) | 0.78(0.62,0.98) | .01 |

|

| ||||||

|

Digestive Tract

|

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 274 | 281 | 288 | 150 | 77 | 1070 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 0.89(0.75,1.06) | 0.80(0.67,0.94) | 0.82(0.67,1.01) | 0.63(0.49,0.81) | <.001 |

| Multivariablea.d | 1(reference) | 0.93(0.78,1.10) | 0.84(0.70,1.00) | 0.86(0.70,1.06) | 0.66(0.51,0.87) | .003 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 0.94(0.79,1.11) | 0.86(0.72,1.02) | 0.89(0.72,1.10) | 0.69(0.53,0.90) | .01 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 1(reference) | 0.94(0.79,1.12) | 0.86(0.72,1.03) | 0.89(0.72,1.11) | 0.70(0.54,0.91) | .01 |

|

| ||||||

| Upper Digestive Tract (Mouth/Pharynx to Small Intestine) |

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 86 | 74 | 85 | 44 | 20 | 309 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 0.74(0.54,1.01) | 0.72(0.53,0.98) | 0.74(0.51,1.07) | 0.49(0.30,0.80) | .01 |

| Multivariablea | 1(reference) | 0.75(0.54,1.03) | 0.74(0.54,1.02) | 0.76(0.52,1.12) | 0.50(0.30,0.83) | .02 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 0.75(0.55,1.04) | 0.75(0.54,1.03) | 0.78(0.53,1.14) | 0.51(0.30,0.85) | .03 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMb | 1(reference) | 0.76(0.55,1.04) | 0.75(0.54,1.04) | 0.78(0.53,1.15) | 0.51(0.31,0.85) | .03 |

|

| ||||||

| Colorectum

|

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 188 | 207 | 203 | 106 | 57 | 761 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 0.97(0.79,1.18) | 0.83(0.68,1.02) | 0.86(0.67,1.09) | 0.69(0.51,0.94) | .01 |

| Multivariablea | 1(reference) | 1.02(0.83,1.25) | 0.89(0.72,1.10) | 0.92(0.71,1.18) | 0.76(0.55,1.03) | .05 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 1.03(0.84,1.27) | 0.92(0.74,1.13) | 0.95(0.74,1.23) | 0.79(0.58,1.08) | .12 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMb | 1(reference) | 1.04(0.85,1.27) | 0.92(0.75,1.14) | 0.96(0.75,1.24) | 0.80(0.59,1.10) | .13 |

|

| ||||||

|

Digestive Accessory Organs

|

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 69 | 80 | 85 | 32 | 34 | 300 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 0.94(0.68,1.30) | 0.84(0.60,1.16) | 0.61(0.40,0.93) | 0.95(0.62,1.45) | .26 |

| Multivariablea,d | 1(reference) | 0.98(0.71,1.37) | 0.90(0.64,1.26) | 0.65(0.42,1.01) | 1.02(0.66,1.58) | .46 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 0.99(0.71,1.39) | 0.91(0.65,1.28) | 0.67(0.43,1.04) | 1.05(0.68,1.64) | .56 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 1(reference) | 1.00(0.72,1.40) | 0.92(0.66,1.29) | 0.68(0.44,1.06) | 1.08(0.69,1.68) | .63 |

|

| ||||||

| Pancreas

|

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 54 | 66 | 66 | 24 | 25 | 235 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 1.00(0.69,1.43) | 0.84(0.58,1.22) | 0.59(0.36,0.96) | 0.90(0.55,1.46) | .15 |

| Multivariablea | 1(reference) | 1.01(0.70,1.47) | 0.87(0.60,1.28) | 0.62(0.37,1.02) | 0.95(0.57,1.57) | .28 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 1.01(0.70,1.47) | 0.88(0.60,1.28) | 0.62(0.38,1.03) | 0.96(0.58,1.60) | .31 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 1(reference) | 1.02(0.71,1.48) | 0.88(0.60,1.30) | 0.64(0.38,1.05) | 0.99(0.59,1.64) | .36 |

|

| ||||||

| Liver+Gallbladder

|

||||||

| No. of incident cases | 15 | 14 | 19 | 8 | 9 | 65 |

| Age-adjusted | 1(reference) | 0.74(0.35,1.54) | 0.83(0.41,1.65) | 0.68(0.28,1.64) | 1.14(0.49,2.66) | .78 |

| Multivariablea | 1(reference) | 0.85(0.40,1.79) | 1.00(0.49,2.05) | 0.80(0.32,1.98) | 1.30(0.53,3.16) | .61 |

| Multivariable+BMIb | 1(reference) | 0.89(0.42,1.89) | 1.07(0.52,2.22) | 0.88(0.35,2.17) | 1.43(0.58,3.51) | .47 |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 1(reference) | 0.90(0.42,1.90) | 1.08(0.52,2.24) | 0.89(0.36,2.22) | 1.45(0.59,3.57) | .45 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazards ratio; MET, metabolic equivalent task

Multivariable analyses were stratified by age (continuous) and questionnaire cycle; adjusted for Caucasian (yes vs. no), smoking (never, past, current 1-14.9 cigarettes/day, current 15-24.9 cigarettes/day, current 25+ cigarettes/day, unknown status), family history of cancer (yes vs. no), history of physical examination for screening purpose (yes vs. no), current aspirin use (yes vs. no), current multivitamin use (yes vs. no), and intakes of total calories (quintiles), alcohol (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-29.9, 30+ g/day), red and processed meat (quintiles), whole grains (quintiles), fruits (quintiles), and vegetables (quintiles); analysis for mouth/pharynx to small intestine cancers was additionally adjusted for history of upper endoscopy (yes vs. no); analysis for colorectal cancer was additionally adjusted for history of endoscopy and polyps (no endoscopy+no polyp detection, endoscopy+no polyp detection, endoscopy+polyp detection, unknown status).

Multivariable analyses were additionally adjusted for BMI (<23, 23-24.9, 25-29.9, 30-34.9, 35+ kg/m2).

Multivariable analyses were additionally adjusted for history of DM (yes vs. no).

P value for heterogeneity in the linear association across digestive tract cancers and digestive accessory organ cancers was .47.

By type of PA comparing aerobic PA versus weight lifting (Table 3), the greatest reduction in DSC risk occurred in the most active group exclusively engaging in aerobic PA (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.41-0.72). The dose-response curve controlled for weight lifting and other confounders suggested that most of the benefit on DSC risk occurred up to approximately 30 MET-hours/week of aerobic PA, with little incremental benefit thereafter (Pnon-linearity =0.02) (Figure 1). Compared to the risk at 1 MET-hours/week, the risk reduced by 32% at 30 MET-hours/week (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56-0.83). Regarding intensity of aerobic PA, as long as the same MET-hour score was achieved from walking at least at average pace, jogging, and running, participation in more intense one did not lead to a greater reduction in DSC risk (Table 4). The dominant benefit of aerobic PA, non-linearity of curve, and irrelevance of intensity (see eTable 3, eFigure 2, eTable 4, respectively, in the Supplement) were more consistently observed with digestive tract cancers than with digestive accessory organ cancers.

Table 3.

HR and 95% CI for Joint Associations of Amount of Aerobic Exercise/Weight Lifting and Participation in Weight Lifting with Digestive System Cancers

| Aerobic Exercise/Weight Lifting (median, MET-hours/week)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 3 | 3+ | |||

|

|

||||

| Reference (1.4) | Q1 (8.9) | Q2 (22.4) | Q3 (47.5) | |

|

Participation in Weight Lifting

|

||||

| No | ||||

| No. of incident cases (person-years) | 221(102,919) | 158(76,642) | 104(52,933) | |

| Multivariableb | 0.64(0.50,0.80) | 0.59(0.46,0.76) | 0.54(0.41,0.72) | |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 105(31,865) | 0.65(0.51,0.82) | 0.61(0.47,0.78) | 0.57(0.43,0.76) |

| 1 (reference) | ||||

| Yes | 1 (reference) | |||

| No. of incident cases (person-years) | 82(39,423) | 112(66,288) | 152(90,096) | |

| Multivariableb | 0.77(0.57,1.04) | 0.61(0.46,0.81) | 0.61(0.47,0.80) | |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMc | 0.79(0.59,1.07) | 0.64(0.48,0.85) | 0.65(0.50,0.85) | |

The cut-off for the reference group was chosen to represent the minimal among multiples of 3 MET-hours/week; non-reference group was categorized based on tertiles to balance data across joint categories, which helps obtain reliable estimates.

Multivariable analyses were adjusted for the same set of variables as denoted in Table 2.

Multivariable analyses were adjusted for the same set of variables as denoted in Table 2.

Figure 1. Relationship between Aerobic Physical Activity and Digestive System Cancer Risk.

HR (95% CI) was adjusted for participation in weight lifting (yes versus no) and the same set of variables as denoted in Table 2; was 0.83 (0.74, 0.92) at 11 MET-hours/week, 0.68 (0.56, 0.83) at 30 MET-hours/week, and 0.68 (0.56, 0.82) at 42 MET-hours/week. P value comparing the fit of non-linear versus linear model was 0.02; P value for overall significance of curve was <0.001.

Table 4.

HR and 95% CI for Joint Associations of Amount of Walking/Jogging/Running and Intensity with Digestive System Cancers

| Walking/Jogging/Running (median, MET-hours/week)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 3 | 3+ | |||

|

|

||||

| Reference (1.0) | Q1 (5.4) | Q2 (13.5) | Q3 (31.5) | |

|

Average METb

|

||||

| ≤ 4.5 | ||||

| No. of incident cases (person-years) | 291(140,093) | 251(113,428) | 196(80,015) | |

| Multivariablec | 0.85(0.72,1.00) | 0.80(0.67,0.95) | 0.79(0.66,0.95) | |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMd | 324(140,748) | 0.86(0.73,1.01) | 0.82(0.69,0.97) | 0.82(0.68,0.99) |

| 1 (reference) | ||||

| > 4.5 | 1 (reference) | |||

| No. of incident cases (person-years) | 37(28,916) | 78(57,662) | 123(90,782) | |

| Multivariablec | 0.76(0.54,1.07) | 0.83(0.64,1.07) | 0.80(0.64,0.99) | |

| Multivariable+BMI+DMd | 0.79(0.56,1.11) | 0.87(0.67,1.12) | 0.85(0.69,1.06) | |

The cut-off for the reference group was chosen to represent the minimal among multiples of 3 MET-hours/week; non-reference group was categorized based on tertiles to balance data across joint categories, which helps obtain reliable estimates.

Weighted average of MET values of walking (at normal, brisk, or very brisk pace), jogging, and running using weekly hours spent for each activity as the weight

Multivariable analyses were adjusted for the same set of variables as denoted in Table 2

Multivariable analyses were adjusted for the same set of variables as denoted in Table 2

Discussion

In men, a higher level of total PA as indicated by MET-hours/week was associated with a lower risk of DSC, particularly digestive tract cancers. By type of PA, aerobic PA rather than resistance PA underlay the inverse association, with its benefit plateauing after about 30 MET-hours/week. Moreover, as long as the same level of MET-hour score was achieved from aerobic PA, the magnitude of risk reduction was similar regardless of intensity of aerobic PA.

Several mechanisms may explain our findings. PA is associated with reduced levels of circulating insulin and bioavailable insulin-like growth factor-I, the two major mitogenic hormones implicated in carcinogenesis.20 PA is also known to enhance anti-cancer immune function and anti-oxidant defenses.20 Some mechanisms may be more specific to digestive tract cancers. The COX-2 is overexpressed in several digestive tract cancers21-24 and PA reduces COX-2 mediated inflammatory response.4 Additionally, PA reduces exposure of the digestive tract to carcinogens by stimulating gastrointestinal motility and thereby reducing gastrointestinal transit time.20 Finally, a higher predicted score of plasma 25-hydroxy-vitamin D level was largely associated with a reduced incidence for digestive tract cancers but not for other cancers in our cohort.25 PA, particularly outdoor PA, may reduce digestive tract cancer risk by improving vitamin D status through sun exposure.

Despite the aforementioned biological plausibility, our current understanding on the relationship between PA and DSC risk is largely limited. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research expert panel judged that the evidence for a causal effect of PA is convincing only for colon cancer.26 Our study provide additional insight into digestive tract cancers that an inverse association of PA with upper digestive tract cancers was strong and independent of BMI and DM, whereas that with colorectal cancer was partially explained by BMI. The differential degree to which BMI explains the associations is in part attributable to the fact that excess adiposity is an established risk factor for colorectal cancer,16 while it forms divergent relationships with upper digestive tract cancers.16,27 Alternatively, in light that primary exposure to foods containing carcinogens or pro-oxidants occurs along the upper digestive tract, reduced gastrointestinal transit time and enhanced anti-oxidant defense promoted by PA20 might be particularly relevant to upper digestive tract cancers. Indeed, in our stratified analyses, an inverse association was pronounced among unhealthy eaters more likely vulnerable to carcinogenic and oxidative damage (see eFigure 2 in the Supplement). A recent meta-analysis also found an inverse relation of PA with gastroesophageal cancers independent of adiposity.28

Aerobic and resistance exercises represent two major types of PA. While both forms help regulate blood levels of glucose and lipids, aerobic PA is particularly effective at improving cardiorespiratory fitness whereas resistance PA is at increasing muscular strength.29 To date, the relative importance of aerobic versus resistance PA in relation to cancer risk has not been a focus of study, but our findings suggest those with low overall PA prioritize aerobic PA over resistance PA to achieve a greater reduction in DSC risk. As a potential explanation, cardiorespiratory fitness, which has been inversely associated with DSC mortality,30 may be the relevant parameter. Additionally, aerobic PA may be more beneficial to gastrointestinal motility31 and anti-oxidant defenses,20 important determinants of DSC risk.

Our finding that intensity of aerobic PA does not matter as much as amount of aerobic MET-hour scores achieved supports the PA guideline for cancer prevention.6 The two exercise regimes by ACS, while based on different intensity and duration of PA, translate into a recommendation to accumulate roughly at least 11 MET-hours/week.6 Our dose-response curve estimates that individuals meeting the guideline through aerobic PA can reduce DSC risk at least by 17%, with the optimal benefit achieved at around 30 MET-hours/week. Given the irrelevance of intensity of aerobic exercise, walking about 90 minutes/day at average pace, an exercise regime that can be readily incorporated into everyday life, may be sufficient to reap the optimal benefit of PA against DSC.

There are several limitations in our study. First, we might have underestimated the true benefit of PA against DSC because of measurement error in self-reported PA. Yet, our use of the cumulative average of PA assessed at multiple time points reduced the degree of measurement error. Second, our total MET-hour score might have underestimated overall PA as the questionnaire included select activities. Nevertheless, previous studies from our cohort wherein self-reported PA predicted diverse disease outcomes32-34 provide qualitative evidence for the capability of our questionnaire to discriminate PA levels. Third, lower MET-hours/week for weight lifting than for aerobic exercise may have contributed to greater benefit observed with aerobic exercise. Yet, the degree of weight lifting in our cohort was sufficient to predict other diseases35,36 and to form even a stronger association than aerobic exercise with waist circumference maintenance.32 Finally, due to heterogeneity in the magnitude of the association by cancer site, our findings are not generalizable to a population with a markedly different distribution of DSC incidence.

Yet, our study has strengths. We examined potential interactions between diverse domains of PA in relation to DSC risk. By cumulatively updating PA, we reflected a long-term average likely more relevant to the carcinogenic process spanning several decades. While our cohort consisting of primarily male white health professionals may limit the representativeness of the findings, our estimates are less susceptible to confounding by health-conscious lifestyles and socioeconomic status. Furthermore, as risk factors vary across DSC, they form a weaker association with a composite endpoint, which reduces the degree of confounding in our analyses. Also, given the large effect size, the observed association from our multivariable analyses is unlikely to be entirely attributable to confounding.

In conclusion, PA, as indicated by MET-hour score may be inversely associated with the risk of DSC, particularly digestive tract cancers, in men, with the optimal benefit observed through aerobic exercise of any intensity at the equivalent of energy expenditure of approximately 10 hours/week of walking at average pace. Future studies are warranted to further investigate etiological mechanism underlying the optimal dose, type, and intensity of exercise and to evaluate preventive potential of exercise against overall DSC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the HSPF for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (UM1 CA167552). Dr Bao is funded by the National Institutes of Health (U54 CA155626, P30 DK046200, and KL2 TR001100).

Role of the Funders/Sponsors: None of the funders/sponsors had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication

Footnotes

Article Contributions: Dr Keum had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Keum, Smith-Warner, Orav, Giovannucci.

Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: All authors

Drafting of the manuscript: Keum

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Statistical analysis: Keum, Bao, Orav, Smith-Warner, Giovannucci

Study supervision: Giovannucci.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors declared no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Dong J, Dai J, Zhang M, Hu Z, Shen H. Potentially functional COX-2-1195G>A polymorphism increases the risk of digestive system cancers: a meta-analysis. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2010 Jun;25(6):1042–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. The Lancet Oncology. 2012 May;13(5):518–527. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langley RE, Rothwell PM. Aspirin in gastrointestinal oncology: new data on an old friend. Current opinion in oncology. 2014 Jul;26(4):441–447. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YY, Yang YP, Huang PI, et al. Exercise suppresses COX-2 pro-inflammatory pathway in vestibular migraine. Brain research bulletin. 2015 Jul;116:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Imamura Y, et al. Physical Activity, Tumor PTGS2 Expression, and Survival in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2013 Jun;22(6):1142–1152. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):30–67. doi: 10.3322/caac.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GLOBOCAN. Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, et al. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in men. Lancet. 1991 Aug 24;338(8765):464–468. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90542-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of Physical Activities - Classification of Energy Costs of Human Physical Activities. Med Sci Sport Exer. 1993 Jan;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology. 1996 Jan;7(1):81–86. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199601000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, et al. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1993 Jul;93(7):790–796. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91754-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. American journal of epidemiology. 1992 May 15;135(10):1114–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. ; discussion 1127-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. London; New York: Chapman and Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu F. Obesity Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon CY, Lokken RP, Hu FB, van Dam RM. Physical activity of moderate intensity and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes care. 2007 Mar;30(3):744–752. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The U.S. National Cancer Institute Obesity and Cancer Risk. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/obesity. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- 17.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes care. 2010 Jul;33(7):1674–1685. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ML, Spiegelman D, Kuchiba A, et al. Statistical methods for studying disease subtype heterogeneity. Statistics in medicine. 2016 Feb 28;35(5):782–800. doi: 10.1002/sim.6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Statistics in medicine. 1989 May;8(5):551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedenreich CM, Orenstein MR. Physical activity and cancer prevention: etiologic evidence and biological mechanisms. The Journal of nutrition. 2002 Nov;132(11 Suppl):3456S–3464S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urade M. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 as a potent molecular target for prevention and therapy of oral cancer. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2007;44:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmermann KC, Sarbia M, Weber AA, Borchard F, Gabbert HE, Schror K. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999 Jan 1;59(1):198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ristimaki A, Honkanen N, Jankala H, Sipponen P, Harkonen M. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997 Apr 1;57(7):1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eberhart CE, Coffey RJ, Radhika A, Giardiello FM, Ferrenbach S, DuBois RN. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression in human colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology. 1994 Oct;107(4):1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006 Apr 5;98(7):451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Cancer Research Fund /American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Report. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. 2011 http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/cancer_resource_center/downloads/cu/Colorectal-Cancer-2011-Report.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2015.

- 27.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008 Feb 16;371(9612):569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrens G, Jochem C, Keimling M, Ricci C, Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. The association between physical activity and gastroesophageal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of epidemiology. 2014 Mar;29(3):151–170. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9895-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock ML, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. AHA Science Advisory. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: benefits, rationale, safety, and prescription: An advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association; Position paper endorsed by the American College of Sports Medicine. Circulation. 2000 Feb 22;101(7):828–833. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.7.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peel JB, Sui X, Matthews CE, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and digestive cancer mortality: findings from the aerobics center longitudinal study. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2009 Apr;18(4):1111–1117. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YS, Song BK, Oh JS, Woo SS. Aerobic exercise improves gastrointestinal motility in psychiatric inpatients. World J Gastroentero. 2014 Aug 14;20(30):10577–10584. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mekary RA, Grontved A, Despres JP, et al. Weight training, aerobic physical activities, and long-term waist circumference change in men. Obesity. 2015 Feb;23(2):461–467. doi: 10.1002/oby.20949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chomistek AK, Chiuve SE, Jensen MK, Cook NR, Rimm EB. Vigorous physical activity, mediating biomarkers, and risk of myocardial infarction. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2011 Oct;43(10):1884–1890. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821b4d0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Chan JM. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Feb 20;29(6):726–732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grontved A, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Andersen LB, Hu FB. A prospective study of weight training and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 Sep 24;172(17):1306–1312. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanasescu M, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Exercise type and intensity in relation to coronary heart disease in men. Jama. 2002 Oct 23–30;288(16):1994–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.