Abstract

Background:

Association of neutrophil function abnormalities with localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP) has been reported in Indian population. There are no published studies on the familial aggregation of aggressive periodontitis (AP) and neutrophil function abnormalities associated with it in Indian population. The present study aimed to assess neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and microbicidal activity in AP patients and their family members of Indian origin, who may or may not be suffering from AP.

Materials and Methods:

Eighteen families with a total of 51 individuals (18 probands, 33 family members) were included. Neutrophil chemotaxis was evaluated against an alkali-soluble casein solution using Wilkinson's method. Phagocytosis and microbicidal activity assay were performed using Candida albicans as an indicator organism.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The magnitude of association between the presence of defective neutrophil function and LAP or GAP was calculated using odds ratio and relative risk. Total incidence of AP, and in particular, LAP in the families attributable to the presence of defective neutrophil function was calculated by attributable risk.

Results:

The association between depressed neutrophil chemotaxis and presence of AP and LAP or GAP in all the family members (n = 51) was found to be significant (P < 0.05) while that for phagocytic and microbicidal activity were observed to be nonsignificant.

Conclusion:

The results of the present study suggest high incidence of AP (LAP and GAP) within families was associated with depressed neutrophil chemotaxis. High prevalence of depressed neutrophil chemotaxis in the family members (61%) of LAP probands exhibiting depressed chemotaxis suggests that the observed abnormalities in neutrophil functions may also be inherited by the family members.

Keywords: Abnormal neutrophil function, familial aggregation, Indian population, localized aggressive periodontitis

INTRODUCTION

Neutrophils form the first line of defense against the invading microorganisms and play an essential part in the host's inflammatory response. In aggressive periodontitis (AP), the characteristic clinical findings include tissue destruction, which is not commensurate with the amount of plaque present. Furthermore, one of the distinguishing laboratory features between localized AP (LAP) and generalized AP (GAP) is a robust serum antibody response in LAP patients. Collectively, this suggests that some form of increased host susceptibility may form an important aspect of etiology for this group of diseases.[1] Several systemic diseases associated with a defective neutrophil number or function, such as cyclic neutropenia,[2] Chediak–Higashi Syndrome,[3] leukocyte adhesion deficiency,[4] Papillon–Lefevre Syndrome,[5] and Down's Syndrome[6] are also associated with severe forms of periodontal destruction, further corroborating the evidence for association between neutrophil dysfunction and host susceptibility to destructive form of periodontal disease like AP.

The current paradigm of etiopathogenesis suggests greater role of host (genetic and immunological) factors that may predispose to altered inflammatory or immunological processes.[7,8] However, there are still many uncertainties regarding the genetic etiologic factors, as not only the gene/s involved are still unclear,[9,10] but even the mode of inheritance remains under discussion.[7,11,12,13,14] Furthermore, the racial predilection and preponderance of occurrence in one sex varies with the population studies being reported.[15,16]

The role of neutrophil function in LAP may serve as a model system to understand periodontal pathology as a result of host-related functional abnormalities while presenting a local phenomenon in which neutrophil-mediated tissue injury occurs.[17,18] The neutrophil functions associated with increased susceptibility to LAP[17,18] include neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and intracellular killing of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, superoxide generation, surface receptor expression, leukotriene B4 (LTB4) synthesis, and signal transduction.

The prevalence of LAP in Indian population is reported to vary from 0.1%[15] and 6.83%[19] to 35%.[16] Very few studies have investigated the association of neutrophil function abnormalities with LAP in Indian population.[20] However, there are no published data on the familial aggregation of AP and neutrophil function abnormalities associated with it in Indian population. Hence, the present study aimed to assess neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and microbicidal activity in patients with AP and their family members of Indian origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of patients

Ethical approval for the present study was obtained from the local research ethics review committee. All the family members participating in the present study signed informed consent form. In case of minors, consent form was signed either by parents or elder sibling above the age of 18 years.

Test group

A total of 18 families (51 participants; 42 females: nine males), each consisting of the proband and at least one other sibling, participated in the present study. The proband for each family (18 participants; 16 females: two males) and their family members were selected based on their periodontal conditions. Two separate investigators assigned the clinical diagnosis of AP based on the criteria suggested by Lang et al.[1] Individuals over the age of 30 years provided previous case records and radiographs to assign a diagnosis of AP.

The exclusion criteria included clinical signs of periodontal disease other than AP, history of known systemic diseases, past periodontal and/or orthodontic treatment, and history of smoking or use of tobacco in any form.

The family members were then divided into three groups based on their periodontal diagnosis. These groups were

Group I – LAP

Group II – GAP

Group III – Healthy without any form of periodontal disease.

A case history pro forma was designed containing complete past and present medical history, past dental history, and past and present personal history, clinical and radiographical evaluation (orthopantomogram and/or intraoral radiographs) along with clinical laboratory examination (complete hemogram and random blood sugar analysis) performed blind to the clinical diagnosis.

Control group

Controls, recruited from the outpatient department of periodontics, were age and sex matched to the test participants. The family members of the controls were also examined, and only those individuals whose family members did not present with clinical signs of AP were recruited. All the controls were systemically healthy without any form of periodontal disease other than mild gingivitis. Informed consent was obtained from the controls.

Collection of blood samples

Six milliliters of whole blood were drawn under strict aseptic condition from the antecubital vein of each participant in two separate vials, one of which contained heparin (15 IU/ml blood) and transported to the laboratory. The vials were coded for easy identification of participants.

Preparation of cells

Neutrophils

After a total and differential count of white blood cells, neutrophils were separated from whole blood by the dextran sedimentation technique described in detail in our previous publication.[20] All the tests were done in the duplicates and controls were simultaneously tested.

Candida albicans

C. albicans organism was grown on Sabouraud's 2% dextrose broth for 48 h at 37°C. This helped obtain organisms in yeast phase, which was used in phagocytosis and microbicidal assays.

Neutrophil function assays

Chemotaxis assay

Chemotaxis assay[21] assembly consisted of two compartments – a lower compartment filled with the chemoattractant casein (in Hank's balanced salt solution, HiMedia Labs, Mumbai, India) and an upper compartment containing neutrophil cell suspension. The upper compartment was made up of a syringe with 5-μm pore size calcium acetate filter paper glued at one end. The upper compartment was inverted over the lower compartment, and the whole assembly was allowed to stand undisturbed for an hour at room temperature. Once time elapsed, the cell contents from upper compartment were emptied. The calcium acetate filter paper end was immersed in 70% methanol to melt the glue and the filter paper strip was carefully removed, stained with hematoxylin, and fixed on glass slides for microscope observation.

Phagocytosis assay

For the phagocytosis assay,[21,22] C. albicans cells were mixed with the neutrophil-rich cell suspension and kept undisturbed for 30 min at 37°C. The whole assembly was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and smears were prepared from the sediment. The smears were air-dried and stained with Giemsa stain for microscopic observation.

Candidacidal assay

The sediment, from phagocytosis assay, was mixed with 2.5% sodium deoxycholate (HiMedia Labs, Mumbai, India) that lysed the leukocytes without any damage to Candida cells. After about 5 min, four ml of 0.01% methylene blue was added to the tubes and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and wet smears were prepared from the sediment for immediate microscopic observation in modified Neubauer's chamber.[21]

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS

The 18 families recruited in the present study comprised of a total of 51 individuals (42 females: 9 males), among them 4 mothers and 47 siblings. Total 18 probands (16 females; 2 males) represented the first patient in each family. Neutrophil functions were evaluated in the individual family members using neutrophil function tests, and defective functions were defined as being two standard deviation above or below (±2 standard deviation) the mean readings for the healthy controls tested concurrently.[20,23]

Distribution of LAP and GAP in the probands and in the rest of the family members is presented in Table 1 and Graphs 1-4.

Table 1.

Distribution of localized aggressive periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis among the probands and the family members

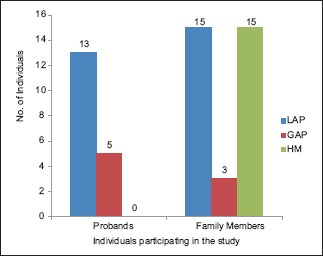

Graph 1.

Distributions of localized aggressive periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis in the probands and the rest of the family members participating in the study. LAP – Localized aggressive periodontitis, GAP – Generalized aggressive periodontitis, HM – Healthy members

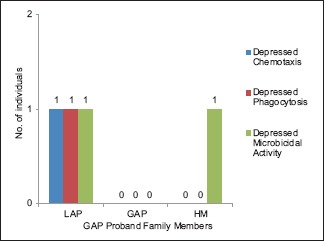

Graph 4.

Distribution of defective neutrophil functions in family members of the probands with generalized aggressive periodontitis and respective neutrophil function defect. LAP – Localized aggressive periodontitis, GAP – Generalized aggressive periodontitis, HM – Healthy members

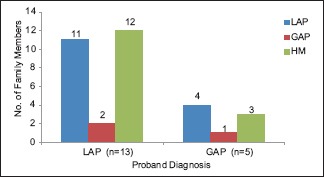

Graph 2.

Prevalence of localized aggressive periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis among the family members of the respective probands. LAP – Localized aggressive periodontitis, GAP – Generalized aggressive periodontitis, HM – Healthy members, n - sample size

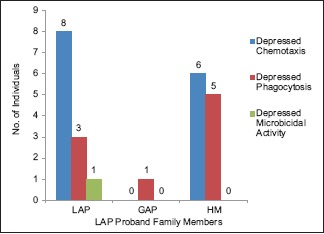

Graph 3.

Distribution of defective neutrophil functions in family members of the probands with localized aggressive periodontitis and respective neutrophil function defect. LAP – Localized aggressive periodontitis, GAP – Generalized aggressive periodontitis, HM – Healthy members

Distribution of abnormal neutrophil function among the studied groups is presented in Table 2. Out of 13 probands with LAP, 12 had depressed chemotaxis, eight showed reduced phagocytosis and two showed reduced microbicidal activity. Among the five GAP probands, two showed chemotactic depression while reduced phagocytic and microbicidal activity was observed in one proband each.

Table 2.

Distribution of abnormal neutrophil functions among all the participating family members

Among the 33 family members, depressed neutrophil chemotaxis was reported in 17 members, reduced phagocytosis in 11 members, and reduced microbicidal activity in 6 family members.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test

The association between depressed neutrophil chemotaxis activity and presence of AP in all the family members is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association between defective neutrophil functions and aggressive periodontitis among the participating individuals tested by Chi-square test at 1° freedom

Among the family members with both AP and abnormal neutrophil functions, the association between the depressed chemotaxis and presence of LAP or GAP is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Association between defective neutrophil functions and localized aggressive periodontitis or generalized aggressive periodontitis among the individuals with aggressive periodontitis tested by Chi-square test at 1° freedom

Odds ratio

It calculated the odds of having AP among all the family members and LAP or GAP among the individuals suffering from AP given that a neutrophil defect is present [Tables 5 and 6].

Table 5.

Magnitude of association between depressed neutrophil chemotaxis and occurrence of aggressive periodontitis calculated by odds ratio and relative risk. Influence of depressed neutrophil chemotaxis on occurrence of aggressive periodontitis calculated by attributable risk

Table 6.

Magnitude of association between depressed neutrophil chemotaxis and occurrence of localized aggressive periodontitis calculated by odds ratio and relative risk. Influence of depressed neutrophil chemotaxis on the occurrence of localized aggressive periodontitis calculated by attributable risk

Relative risk

Measured the association between AP in family members (n = 51) and depressed neutrophil chemotaxis [Table 5] while that for LAP and GAP in family members with AP is presented in Table 6.

Attributable risk

It represents the portion of the incidence of a disease in the exposed individuals that is due to the exposure. The attributable risk for AP in family members that is attributable to the presence of depressed neutrophil chemotaxis is presented in Table 5. Similarly, the total incidence of LAP among the AP members attributed to the presence of depressed neutrophil chemotaxis is presented in Table 6.

DISCUSSION

Unlike other forms of periodontal disease, AP has been associated with various abnormalities in host cell functions. Most of the reports have emphasized the role of defective neutrophil functions as a predisposing factor for AP, in particular, LAP.

The present study comprised of total 18 probands (16 females, 2 males) recruited on the basis of their clinical diagnosis of either LAP or GAP and their family members. The high prevalence of AP (70.59%), especially LAP (54.90%) in the AP families and their preponderance in female sex in the present study may be an overestimate as not all the members in the families were examined. The observed high prevalence in females may also be due to ascertainment bias and in general unwillingness of the male members in the families to participate in the study.

Literature reports neutrophil chemotaxis defects in almost 70–75% of LAP patients.[13,24,25] The present study reported high incidence of AP (LAP and GAP) associated with depressed neutrophil chemotaxis, which corroborated the findings from the earlier studies.[11,23,26,27,28,29,30] The high prevalence of depressed chemotaxis in members affected with LAP (78.5%) as well as in the family members (61%) of LAP probands correlated well with the high prevalence of LAP ascertained clinically. Hence, the present study also suggests that the observed abnormalities in neutrophil functions may also be inherited by the family members.

Research in the underlying mechanisms for depressed neutrophil chemotaxis in LAP have emphasized on various mechanisms that include intrinsic cellular or cytoskeletal defect of neutrophils,[4,13,31] reduced receptor density for chemoattractants such as N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine complement fragment C5a[32,33] and LTB4,[22,34] abnormal signal transduction after receptor-ligand interaction, as measured by decreased influx of extracellular calcium,[35] defective calcium influx factor activity,[36] reduced levels of protein kinase C (PKC),[37] reduced diacylglycerol (DAG) kinase and increased DAG levels,[31,38,39] reduced levels of surface glycoprotein GP110,[40,41] and elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 in serum.[42]

Neutrophil phagocytosis and microbicidal activity were assessed using C. albicans as an indicator organism as it distinguishes between the attached and ingested yeast cells that is not possible with the use of either zymosan or bacteria. The association between reduced phagocytosis and microbicidal activity and presence of AP within the family members was nonsignificant (P > 0.05) suggesting that the presence of AP may not be associated with defective neutrophil phagocytic and microbicidal activity in studied population. The results of the present study were in accord with the results of the earlier studies.[27,43,44]

The mechanisms underlying defective phagocytosis and intracellular killing, though not thoroughly studied, have been attributed to intrinsic cellular or cytoskeletal defects of neutrophils,[45] interference of A. actinomycetemcomitans with phagosome and lysosome fusion by LAP neutrophils and suppression of lactoferrin release[27] along with elevation of superoxide production and signal transduction abnormalities such as chronic PKC activation due to elevated levels of DAG.[46]

Thus, in the present family study, high prevalence of AP, especially LAP was reported among the family members of 18 probands.

Contrasting observations from different laboratories, regarding an association between presence of abnormal neutrophil function and AP, may be attributed to variations in experimental techniques and interpretation of data; lack of definitive diagnostic criteria and insufficient documentation for retrospective diagnosis, lack of sufficient multigenerational data, and sex, age, and racial differences[47] among the population studied.

The limitations of the present study included small sample size that is nonrepresentative of the Indian population and noninclusion of immunological findings in the diagnosis of LAP and GAP. The neutrophil chemotaxis assay in the present study was performed using a single concentration of casein (5 mg/ml), whereas more than one concentration could have elucidated neutrophil response to different gradients of chemoattractants. Furthermore, all the family members were evaluated for abnormal neutrophil functions only once. The day-to-day variations in normal neutrophil functions warranted evaluation of all family members on more than one occasion, on different days repetitively, which was not clinically or practically viable.

CONCLUSION

These intriguing findings favor the notion that defects in neutrophil function such as chemotaxis associated with AP and may serve as predisposing factors for AP, specifically for LAP in individuals of Indian origin. The findings also support the hypothesis that suggests that defects in neutrophil chemotaxis may also be inherited along with the clinical occurrence of AP. However, further studies with a bigger sample size are required to elaborate more on the cause-and-effect association of microbiological, immunological, and genetic factors predisposing to AP and the molecular aspects underlying the etiopathogenesis of AP.

As the complexity in etiopathogenesis of AP resolves, the future therapeutic interventions would focus on correcting the host-related inherited defects either through genetic regulation of neutrophil subcellular mechanisms, anti-bacterial lipopolysaccharide immunization or use of lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins stable analogs to regulate the primed or hyperactive neutrophils in AP.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Colgate Pharmaceuticals India Pvt. Ltd.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the teaching staff at department of Microbiology, Maratha Mandal's Dental College & research Centre, Belgaum, the Dean, GDC & H, Nagpur and Dr. Vaibhav Karemore, Asso. Prof., department of Periodontics, GDC & H Nagpur, for their cooperation and support during this research study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lang N, Murakami S, Bartold M, Cullinan M, Jeffcoat M, Mombelli A, et al. International classification workshop: Consensus on aggressive periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen DW, Morris AL. Periodontal manifestations of cyclic neutropenia. J Periodontol. 1961;32:159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tempel TR, Kimball HR, Kakenashi S, Amen CR. Host factors in periodontal disease: Periodontal manifestations of Chediak-Higashi syndrome. J Periodontal Res. 1972;10:26–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page RC, Beatty P, Waldrop TC. Molecular basis for the functional abnormality in neutrophils from patients with generalized prepubertal periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:182–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dyke TE, Taubman MA, Ebersole JL, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Smith DJ, et al. The Papillon-fevere syndrome: Neutrophil dysfunctions with severe periodontal disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1984;31:419–29. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(84)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan AJ, Evans HE, Glass L, Skin YH, Almonte D. Defective neutrophil chemotaxis in patients with Down's syndrome. J Pediatr. 1975;87:87–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalowicz BS. Genetic and heritable risk factors in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1994;65:479–88. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.5s.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stabholz A, Soskolne WA, Shapira L. Genetic and environmental risk factors for chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010;53:138–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boughman JA, Halloran SL, Roulston D, Schwartz S, Suzuki JB, Weitkamp LR, et al. An autosomal-dominant form of juvenile periodontitis: Its localization to chromosome 4 and linkage to dentinogenesis imperfecta and gc. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1986;6:341–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart TC, Marazita ML, McCanna KM, Schenkein HA, Diehl SR. Reevaluation of the chromosome 4q candidate region for early onset periodontitis. Hum Genet. 1993;91:416–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00217764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marazita ML, Burmeister JA, Gunsolley JC, Koertge TE, Lake K, Schenkein HA, et al. Evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance and race-specific heterogeneity in early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1994;65:623–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart TC, Kornman KS. Genetic factors in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:202–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Xu L, Hasturk H, Kantarci A, DePalma SR, Van Dyke TE, et al. Localized aggressive periodontitis is linked to human chromosome 1q25. Hum Genet. 2004;114:291–7. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:39–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miglani DC, Sharma OP. Report of the enquiry “incidence of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis and periodontosis” among cases seen at the government hospital, madras. J All India Dent Assoc. 1965;37:183–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall-Day CD, Shourie KL. A roentgenographic survey of periodontal disease in India. J Am Dent Assoc. 1949;39:572–88. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1949.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kantarci A, Oyaizu K, Van Dyke TE. Neutrophil-mediated tissue injury in periodontal disease pathogenesis: Findings from localized aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:66–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryder MI. Comparison of neutrophil functions in aggressive and chronic periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010;53:124–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao SS, Tewani SV. Prevalence of periodontitis among Indians. J Periodontol. 1968;39:27–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.1968.39.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhansali RS, Yeltiwar RK, Bhat KG. Assessment of peripheral neutrophil functions in patients with localized aggressive periodontitis in the Indian population. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:731–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.124485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson PC. Assays of leukocyte locomotion and chemotaxis. J Immunol Methods. 1998;216:139–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehrer RI, Cline MJ. Interaction of Candida albicans with human leukocytes and serum. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:996–1004. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.3.996-1004.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki JB, Collison BC, Falkler WA, Jr, Nauman RK. Immunologic profile of juvenile periodontitis. II. Neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis and spore germination. J Periodontol. 1984;55:461–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.8.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Dyke TE, Levine MJ, Tabak LA, Genco RJ. Reduced chemotactic peptide binding in juvenile periodontitis: A model for neutrophil function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;100:1278–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalmar JR, Arnold RR, van Dyke TE. Direct interaction of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans with normal and defective (LJP) neutrophils. J Periodontal Res. 1987;22:179–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1987.tb01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albandar JM. Prevalence of incipient radiographic periodontal lesions in relation to ethnic background and dental care provisions in young adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:625–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Dyke TE, Horoszewicz HU, Cianciola LJ, Genco RJ. Neutrophil chemotaxis dysfunction in human periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1980;27:124–32. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.124-132.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López NJ. Clinical, laboratory, and immunological studies of a family with a high prevalence of generalized prepubertal and juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1992;63:457–68. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakagawa M, Kurihara H, Nishimura F, Isoshima O, Arai H, Sawada K, et al. Immunological, genetic, and microbiological study of family members manifesting early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:254–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimura F, Nagai A, Kurimoto K, Isoshima O, Takashiba S, Kobayashi M, et al. A family study of a mother and daughter with increased susceptibility to early-onset periodontitis: Microbiological, immunological, host defensive, and genetic analyses. J Periodontol. 1990;61:755–62. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.12.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page RC, Vandesteen GE, Ebersole JL, Williams BL, Dixon IL, Altman LC, et al. Clinical and laboratory studies of a family with a high prevalence of juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:602–10. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.10.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dyke TE, Horoszewicz HU, Genco RJ. The polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMNL) locomotor defect in juvenile periodontitis. Study of random migration, chemokinesis and chemotaxis. J Periodontol. 1982;53:682–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.11.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Dyke TE, Levine MJ, Tabak LA, Genco RJ. Juvenile periodontitis as a model for neutrophil function: Reduced binding of the complement chemotactic fragment, C5a. J Dent Res. 1983;62:870–2. doi: 10.1177/00220345830620080301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Offenbacher S, Scott SS, Odle BM, Wilson-Burrows C, Van Dyke TE. Depressed leukotriene B4 chemotactic response of neutrophils from localized juvenile periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 1987;58:602–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.9.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daniel MA, McDonald G, Offenbacher S, Van Dyke TE. Defective chemotaxis and calcium response in localized juvenile periodontitis neutrophils. J Periodontol. 1993;64:617–21. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibata K, Warbington ML, Gordon BJ, Kurihara H, Van Dyke TE. Defective calcium influx factor activity in neutrophils from patients with localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:797–802. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurihara H, Murayama Y, Warbington ML, Champagne CM, Van Dyke TE. Calcium-dependent protein kinase C activity of neutrophils in localized juvenile periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3137–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3137-3142.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurttia HM, Pelto LM, Leino L. Evidence of an association between functional abnormalities and defective diacylglycerol kinase activity in peripheral blood neutrophils from patients with localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:401–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tyagi SR, Uhlinger DJ, Lambeth JD, Champagne C, Van Dyke TE. Altered diacylglycerol level and metabolism in neutrophils from patients with localized juvenile periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2481–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2481-2487.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Dyke TE, Warbington M, Gardner M, Offenbacher S. Neutrophil surface protein markers as indicators of defective chemotaxis in LJP. J Periodontol. 1990;61:180–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.3.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Dyke TE, Wilson-Burrows C, Offenbacher S, Henson P. Association of an abnormality of neutrophil chemotaxis in human periodontal disease with a cell surface protein. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2262–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2262-2267.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal S, Suzuki JB, Riccelli AE. Role of cytokines in the modulation of neutrophil chemotaxis in localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1994;29:127–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paknejad M, Rokn AR, Touhid AH. An investigation on chemotaxis activity, respiratory explosion and the phagocytosis of peripheral blood neutrophils in patients affected with early-onset periodontitis. J Dent (Tehran) 2004;1:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vandesteen GE, Williams BL, Ebersole JL, Altman LC, Page RC. Clinical, microbiological and immunological studies of a family with a high prevalence of early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1984;55:159–69. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.3.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cainciola LJ, Genco RJ, Patters MR, McKenna J, van Oss CJ. Defective polymorphonuclear leukocyte function in a human periodontal disease. Nature. 1977;265:445–7. doi: 10.1038/265445a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Dyke TE, Lester MA, Shapira L. The role of the host response in periodontal disease progression: Implications for future treatment strategies. J Periodontol. 1993;64:792–806. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.8s.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schinkein HA, Best AM, Gunsolley JC. Influence of race and periodontal clinical status on neutrophil chemotactic response. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:272–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]