Abstract

Background:

Osteoporosis is particularly high in females, the early identification of which remains a challenge. Panoramic radiographs are routinely advised to detect periodontal diseases and can be used to predict low bone mineral density (BMD). Hence, this investigation was aimed to identify the risk of osteoporosis in pre- and postmenopausal periodontally healthy and chronic periodontitis women with digital panoramic radiographs.

Materials and Methods:

The study population consisted of 120 patients equally divided as Group I - Premenopausal periodontally healthy, Group II - Premenopausal periodontitis, Group III - Postmenopausal periodontally healthy, and Group IV - Postmenopausal periodontitis. Clinical parameters were recorded, and digital panoramic radiographs were used to record the mental index (MI), panoramic mandibular index (PMI), and mandibular cortical index (MCI) scores.

Results:

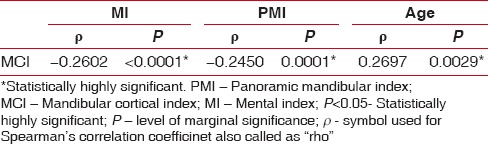

MI was found to be varied, and the differences were highly significant among Group III and IV (P = 0.0003) and Group II and IV (P = 0.0007), and significant difference was found between Group I and Group II (P = 0.0113). MCI evaluation showed a greater prevalence of C2 and C3 patterns among postmenopausal women. MCI correlation with MI (P < 0.0001), PMI (P < 0.0001) and age (P = 0.0029) indicated a highly significant variance.

Conclusion:

The positive association between MCI and chronic periodontitis in postmenopausal women confirms the high risk of osteoporosis in them. Furthermore, an increased percentage of patients with undetected decrease in BMD may be identified by screening with digital panoramic radiographs which are done on a routine basis for periodontal and other dental diseases and thus could be used as an effective aid to quantify bone density in future.

Keywords: Bone mineral density, chronic periodontitis, menopause, osteoporosis, panoramic radiography

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disease characterized by reduced bone mass with an increased susceptibility toward bone fragility and fracture risk. The risk factors for such an occurrence include nonmodifiable ones such as sex, age, early menopause, thin or small body frame, race, and heredity,[1] while the modifiable factors are lack of calcium intake, lack of exercise, alcohol, and smoking.[2,3] The prevalence of osteoporosis is particularly high in females, owing to the changing hormonal levels regulating metabolic processes in the body. A major challenge in combating this disorder lies in the early diagnosis before the occurrence of clinical consequences.

Chronic periodontitis on the other hand is one of the most common inflammatory diseases caused by specific microorganisms, leading to progressive destruction of the connective tissue and alveolar bone.[4,5] Although microbial plaque is considered to be a prerequisite for the initiation and progression of chronic periodontitis, the advanced destruction many a times, it cannot be explained exclusively on the basis of quantitative and/or qualitative analysis of microbial deposits. Reduced bone mass associated with microarchitectural deterioration, as seen in osteoporosis may have a compounding influence on the inflammation-mediated alveolar bone destruction.

Since both osteoporosis and periodontal diseases involve bone resorption as a manifestation of expression and both have common risk factors, it has been hypothesized that osteoporosis could be a risk indicator for progression of periodontal disease.[6,7] Given the complexity and multifactorial nature of periodontal disease, certain systemic conditions including osteoporosis may not only predispose an individual to this disease but also lead to a rapid progression of the disease, creating an even more fragile state.[8] This relationship, though appears to be logical, has not been fairly established owing to contradictory observations. Some studies have obtained a positive and significant relationship between the two conditions;[9,10] however, other have failed to do so.[11,12]

Digital panoramic radiographs have been extensively used in screening and treatment planning for patients affected with periodontal diseases and have been shown to play a critical role in identification and evaluation of osteoporotic patients or those with low mineral density.[13,14] A number of mandibular cortical indices, including the mandibular cortical index (MCI), mental index (MI) and panoramic mandibular index (PMI) have been developed to assess and quantify the quality of mandibular bone mass and to observe signs of resorption on panoramic radiographs. The best established of these is MI which is the mean of the widths of the lower border cortex below the two mental foramina. Osteopenia can be identified by the thinning of the cortex at the lower border of the mandible. A thin mandibular cortical width has been shown to be correlated with reduced skeletal bone mineral density (BMD).[15] MCI describes the porosity of the mandible and is related to the mandibular BMD. The index is found to be a useful method of osteoporosis screening.[16] PMI described by Benson et al. evaluates the cortical thickness normalized for the mandibular size which could be used for the assessment of local bone loss.[17]

Considering these facts, the present study was aimed to identify the risk of osteoporosis in pre- and postmenopausal periodontally healthy and chronic periodontitis women by digital panoramic radiographs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population consisted of 120 female patients visiting the Department of Periodontics and Implantology in our institute from June 2015 to May 2017. The patients were equally allotted to four groups, with the prescribed inclusion criteria.

Group I: Thirty premenopausal periodontally healthy controls in the age range of 30–45 years exhibiting gingival index (GI) score = 0 and probing pocket depth (PPD) ≤3 mm

Group II: Thirty premenopausal chronic periodontitis patients in the age range of 30–45 years exhibiting GI ≥1 and PPD and clinical attachment level (CAL) ≥5 mm and radiographic evidence of bone loss

Group III: Thirty postmenopausal periodontally healthy controls in the age range of 45–65 years[18] exhibiting GI = 0 and PPD ≤3 mm

Group IV: Thirty postmenopausal chronic periodontitis patients in the age range of 45- 65 years exhibiting GI ≥1 and PPD and CAL ≥5 mm and radiographic evidence of bone loss.

Patients who had not undergone hysterectomy or oophorectomy with natural history of menopause were included in postmenopausal group.[18]

The exclusion criteria for the study were all patients who had undergone any sort of periodontal treatment in the past 6 months of the study, with a history of any metabolic disease and using medications, which are likely to have effects on bone metabolism.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The participants signed an informed consent form only after which they were included in the study.

Data collection procedures

All the study participants were required to answer a questionnaire related to socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors, age, race, education level, physical activity, smoking habit, alcohol consumption, age of menarche, and age of menopause.

The participants were then taken up for clinical periodontal examination which included PPD, CAL, plaque index (PI),[19] and GI.[20] Digital panoramic radiograph was obtained for each participant for assessment of the following radiographic indices which were done with the help of a software (KODAK 8000C Digital Panoramic and Cephalometric System and KODAK Dental Imaging Software).

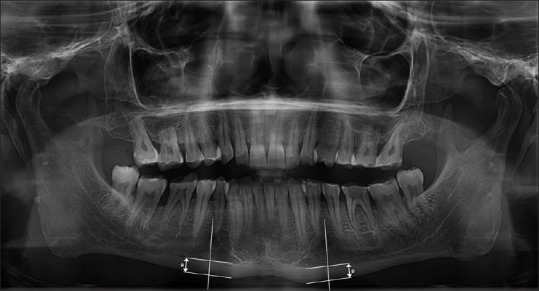

MI: cortical thickness of mandible on a line perpendicular to the bottom of mandible at the center of mental foramen (normal value ≥3.5 mm) [Figure 1][21]

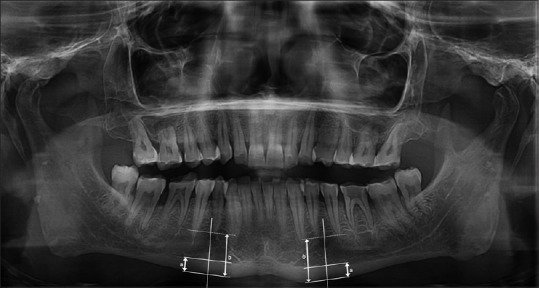

PMI: measured as the ratio of cortical thickness of mandible on perpendicular line to the bottom of mandible at the center of mental foramen to the distance between inferior aspect of mandibular cortex and mandibular bottom (normal value ≥0.3) [Figure 2][21]

-

MCI: it is the division of morphological appearance of inferior mandibular cortex distal to mental foramen as:

- C1 - Endosteal margin is even and sharp on either sides of mandible

- C2 - Endosteal margin with semilunar defects (areas of resorption) and cortical residues one or three layers thick on one or both sides of mandible

- C3 - Endosteal margin consists of thick cortical residues and is amply porous.

Figure 1.

Measurement of the mental index. a: Cortical thickness of mandible on a line perpendicular to the bottom of mandible at the center of mental foramen

Figure 2.

Measurement of panoramic mandibular index (a/b). a: Cortical thickness of mandible on a line perpendicular to the bottom of mandible at the center of mental foramen; b: Distance between inferior aspect of mandibular cortex and mandibular bottom

All the clinical parameters were recorded by a single examiner and the radiographic index evaluation by other examiner. These examiners were calibrated before the study and were blinded to each other's measurements.

Statistical analysis

Demographic, clinical, and radiographic parameters (MI and PMI) were presented as mean standard deviation. Categorical variable (MCI) was expressed in actual numbers and percentages. MI and PMI were compared between two groups by performing unpaired t-test. Association of MCI and four groups were performed by Pearson's Chi-square test. Correlation of age with MI and PMI was assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient (r). Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to assess the correlation between MCI and age and also between MI and PMI. Clinical parameters were compared by unpaired t-test. Statistical software STATA version 14.0, (STATA Corp LLC 4905. Lakeway Drive College Station, Texas 7784545 Lakeway Drive College Station, Texas) was used for data analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 120 female study population, patients were assigned to respective groups and had a mean age of 35.13 ± 4.06, 36.93 ± 3.90, 49.76 ± 3.20, and 53.33 ± 5.22 years from Group I to Group IV, respectively. The clinical periodontal variables demonstrated a significant difference among the study population of all the four groups. The mean PPD was 2.43 ± 0.46 mm, 5.36 ± 0.44 mm, 2.47 ± 0.41 mm, and 6.25 ± 0.71 mm, and the mean CAL observed was 0 mm, 5.67 ± 0.41 mm, 0 mm, and 6.84 ± 0.70 mm for Group I, II, III, and IV, respectively. It was evident that the values of PPD and CAL were significantly greater in periodontally diseased groups as compared to healthy groups in pre- and postmenopausal study patients. The PI and GI also showed similar trends indicating their positive influence over the initiation and progression of periodontal disease.

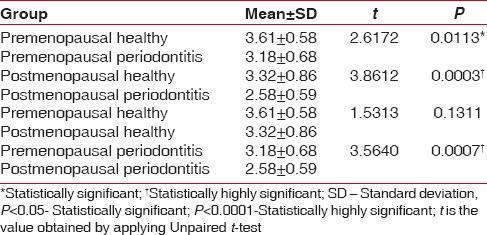

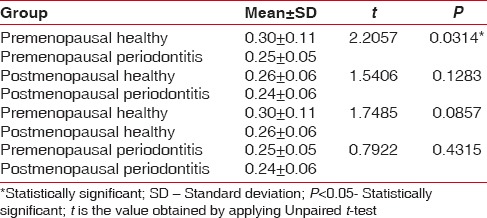

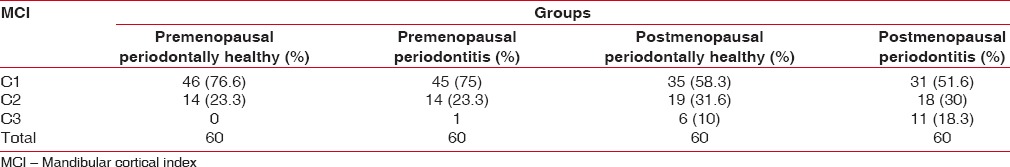

MI was observed to be varied in all the groups with significant differences observed in Group I and Group II, while the differences were highly significant in Group III and Group IV and Group II and Group IV [Table 1]. The mean PMI values differed minimally among the groups, but these differences were not significant [Table 2]. MCI evaluation demonstrated a higher prevalence of C1 pattern in all the study groups, but the incidence of C2 and C3 pattern was found to increase in the postmenopausal population [Table 3].

Table 1.

Comparison of mental index between pre- and postmenopausal groups

Table 2.

Comparison of panoramic mandibular index between pre- and postmenopausal groups

Table 3.

Correlation of mandibular cortical index in pre- and postmenopausal groups

MCI correlation with MI, PMI, and age indicated a highly significant variance [Table 4].

Table 4.

Correlation of mandibular cortical index with mental index, panoramic mandibular index, and age

DISCUSSION

Menopause remains one of the universal milestones in the life cycle of woman and proclaims metamorphosis with a culmination of reproductive years. As is evident with most of the biological phenomenon, differences observed during menopausal transition have possibilities of origin in varied genetics, differing lifestyles and cultures, and many other factors. This transition not only disrupts the menstrual periods but also affects other glands influencing different metabolic processes in the body, thus increasing the risk of various pathologies, including osteoporosis which remains one of the important ones among them. The beginning of menopause in women is accompanied by a number of changes such as reduced salivation, the thinning of the oral mucous membrane, gingival recession, increased prevalence of periodontitis, and alveolar process resorption.[22] With this background, the present study incorporated study groups with and without chronic periodontitis belonging to pre- and postmenopausal status, thus examining the severity of alveolar bone destruction in these groups.

As panoramic radiographic examinations are convenient and informative and are common in odontological practice, we expect this study to serve as an impetus for the advancement of diagnostic and clinical collaboration between dental practitioners and other medical professionals in predicting low general bone mineral index. Due to its feasibility and low exposure time, a large number of digital dental panoramic radiographs have been used for examination of dental and periodontal diseases.[23,24] In fact, in the present study, patients were diagnosed of periodontal disease based on the recommendations of the Madianos et al.,[25] which incorporates clinical as well as radiographic changes. The clinical parameters indicated substantial differences between the healthy controls and periodontitis patients in both pre- and postmenopausal groups. The differences between PPD and CAL in pre- and postmenopausal periodontitis patients were found to be statistically highly significant (P < 0.0001), indicating a greater severity of disease in postmenopausal patients. These findings were also corroborated with a higher score of PI and GI in these patients.

Mandibular bone tissue is a part of the general skeletal bone structure. Various bones are analyzed in studies on BMD. Jagelaviciene et al. performed a study to investigate the relationship between BMD in calcaneus (as determined by dual X-ray and laser osteodensitometry indices). They found statistically significant correlation between the two.[26]

In our study, it was revealed that MI and PMI values in digital panoramic radiographs were reduced in patients affected with periodontitis. These values were further reduced in postmenopausal periodontitis group when compared with premenopausal periodontitis, thus indicating an increase in the severity of the alveolar bone loss. The differences in the MI measurements were highly significant (P = 0.0007), whereas those for PMI did not reach the levels of statistical significance. The results are in agreement with those obtained by Halling et al.[27] and are suggestive of decrease in the cortical bone thickness in gonial region which might be associated with osteoporosis.[28] However, these results also indicate a reduced influence of PMI in predicting a risk of osteoporosis or alveolar bone resorption as have been stated by Alonso et al.[29]

Klemetti et al. suggested that a thin and/or abraded inferior cortex of the mandible is an indicator of alterations in the alveolar bone and is useful in identifying undetected low skeletal BMD or osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.[12] Our study revealed the thickness and shape of mandibular cortex with C1 pattern was 76.6%, 75%, 58.3%, and 51.6% in Group I, Group II, Group III, and Group IV patients, respectively. The patients demonstrating C1 pattern were more in premenopausal group as compared to postmenopausal patients. Furthermore, there was a gross difference and reduction between the percentage of C1 pattern in pre- and postmenopausal periodontitis patients, indicating a more severe erosion of the mandibular cortex in the postmenopausal patients. These findings are in accordance to the findings of Peycheva et al.[24] and Alapati et al.[30]

The present study stands apart from the previous investigations because of the fact that the study population comprised of women belonging to the pre- as well as postmenopausal status, which makes it possible to draw specific conclusions. One of the key factor being minimal difference in mean age groups of patients belonging to the premenopausal (Group I and Group II) and postmenopausal (Group III and Group IV) status. This enabled the authors to remove the empirical confounding bias of higher age among Group I and Group II and Group III and Group IV. Hence, the enhanced periodontal destruction observed in postmenopausal groups cannot only be attributed to the cumulative nature of periodontal destruction but also to the systemic condition prevalent in these patients. The results of our study demonstrated the increased level of significance of MCI in identification of risk group. This finding is in agreement with the study performed by Dagistan and Bilge who investigated and found an association between MCI and osteoporosis.[31] The greater percentage of C2 and C3 pattern of the mandibular cortex observed in postmenopausal healthy controls and periodontitis patients is a pointer toward an unknown influence in the resorption of alveolar bone which most likely is due to the systemic impact. This is more of a concern considering the fact that a longitudinal study on the postmenopausal women showed a positive association between rate of progression of alveolar bone resorption and low systemic BMD.[32]

We used panoramic images which have limitation of magnification. However, we tried to overcome this limitation by applying uniform magnification for all images using the same panoramic machine for screening which had inbuilt system magnification of 1.14. Furthermore, it has been seen that BMD varies with race and ethnicity, and hence, these results may not be considered as universal.

CONCLUSION

The results supported the fact that bone density reduces in postmenopausal women, and the positive association between MCI and chronic periodontitis in postmenopausal women confirms the high risk of osteoporosis in them. Furthermore, it must be emphasized that an increased percentage of patients with undetected decrease in BMD may be identified by screening with digital panoramic radiographs which are done on a routine basis for periodontal and other dental diseases and thus could be used as an effective aid to quantify bone density in future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee BD, White SC. Age and trabecular features of alveolar bone associated with osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holbrook TL, Barrett-Connor E, Wingard DL. Dietary calcium and risk of hip fracture: 14-year prospective population study. Lancet. 1988;2:1046–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cumming RG, Thomas M, Szonyi G, Salkeld G, O’Neill E, Westbury C, et al. Home visits by an occupational therapist for assessment and modification of environmental hazards: A randomized trial of falls prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1397–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LJ, Löe H. Prevalence, extent, severity and progression of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 1993;2:57–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1993.tb00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pischon N, Pischon T, Kröger J, Gülmez E, Kleber BM, Bernimoulin JP, et al. Association among rheumatoid arthritis, oral hygiene, and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2008;79:979–86. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tezal M, Wactawski-Wende J, Grossi SG, Ho AW, Dunford R, Genco RJ, et al. The relationship between bone mineral density and periodontitis in postmenopausal women. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1492–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.9.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inagaki K, Kurosu Y, Yoshinari N, Noguchi T, Krall EA, Garcia RI, et al. Efficacy of periodontal disease and tooth loss to screen for low bone mineral density in Japanese women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77:9–14. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia RI, Henshaw MM, Krall EA. Relationship between periodontal disease and systemic health. Periodontol 2000. 2001;25:21–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.22250103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Wowern N, Klausen B, Kollerup G. Osteoporosis: A risk factor in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1994;65:1134–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.12.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persson RE, Hollender LG, Powell LV, MacEntee MI, Wyatt CC, Kiyak HA, et al. Assessment of periodontal conditions and systemic disease in older subjects. I. Focus on osteoporosis. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:796–802. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elders PJ, Habets LL, Netelenbos JC, van der Linden LW, van der Stelt PF. The relation between periodontitis and systemic bone mass in women between 46 and 55 years of age. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:492–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klemetti E, Collin HL, Forss H, Markkanen H, Lassila V. Mineral status of skeleton and advanced periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:184–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bollen AM, Taguchi A, Hujoel PP, Hollender LG. Case-control study on self-reported osteoporotic fractures and mandibular cortical bone. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:518–24. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.107802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drozdzowska B, Pluskiewicz W, Tarnawska B. Panoramic-based mandibular indices in relation to mandibular bone mineral density and skeletal status assessed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and quantitative ultrasound. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:361–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devlin H, Karayianni K, Mitsea A, Jacobs R, Lindh C, van der Stelt P, et al. Diagnosing osteoporosis by using dental panoramic radiographs: The OSTEODENT project. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:821–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White SC, Taguchi A, Kao D, Wu S, Service SK, Yoon D, et al. Clinical and panoramic predictors of femur bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:339–46. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson BW, Prihoda TJ, Glass BJ. Variations in adult cortical bone mass as measured by a panoramic mandibular index. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:349–56. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taneja P, Meshramkar R, Guttal KS. Assessment of bone mineral density in pre- and post-menopausal women using densitometric software: A pilot study. J Interdiscip Dent. 2015;5:125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taguchi A, Asano A, Ohtsuka M, Nakamoto T, Suei Y, Tsuda M, et al. Observer performance in diagnosing osteoporosis by dental panoramic radiographs: Results from the osteoporosis screening project in dentistry (OSPD) Bone. 2008;43:209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carranza FA, Takei HH. Clinical diagnosis. In: Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, editors. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 541–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koh KJ, Kim KA. Utility of the computed tomography indices on cone beam computed tomography images in the diagnosis of osteoporosis in women. Imaging Sci Dent. 2011;41:101–6. doi: 10.5624/isd.2011.41.3.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peycheva S, Lalabonova H, Daskalov H. Early detection of osteoporosis in patients with 55 using orthopantomography. J IMAB. 2012;18:229–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madianos PN, Bobetsis GA, Kinane DF. Is periodontitis associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease and preterm and/or low birth weight births? J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(Suppl 3):22–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.29.s3.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagelaviciene E, Kubilius R, Krasauskiene A. The relationship between panoramic radiomorphometric indices of the mandible and calcaneus bone mineral density. Medicina (Kaunas) 2010;46:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halling A, Persson GR, Berglund J, Johansson O, Renvert S. Comparison between the klemetti index and heel DXA BMD measurements in the diagnosis of reduced skeletal bone mineral density in the elderly. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:999–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1796-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikebe K, Morii K, Kashiwagi J, Nokubi T, Ettinger RL. Impact of dry mouth on oral symptoms and function in removable denture wearers in Japan. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:704–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso MB, Cortes AR, Camargo AJ, Arita ES, Haiter-Neto F, Watanabe PC, et al. Assessment of panoramic radiomorphometric indices of the mandible in a Brazilian population. ISRN Rheumatol. 2011;2011:854287. doi: 10.5402/2011/854287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alapati S, Reddy RS, Tatapudi R, Kotha R, Bodu NK, Chennoju S, et al. Identifying risk groups for osteoporosis by digital panoramic radiography. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:S253–7. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.166833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dagistan S, Bilge OM. Comparison of antegonial index, mental index, panoramic mandibular index and mandibular cortical index values in the panoramic radiographs of normal males and male patients with osteoporosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010;39:290–4. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/46589325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geurs NC, Lewis CE, Jeffcoat MK. Osteoporosis and periodontal disease progression. Periodontol 2000. 2003;32:105–10. doi: 10.1046/j.0906-6713.2003.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]