Abstract

Correct diagnosis of white lesions of the oral cavity is sometimes difficult, because some oral white lesions behave differently and tend to change their appearance with time. Clinicians often wrongly diagnose such lesions as oral leukoplakias and treat simply. Lesions recur and turn malignant. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is a distinct form of oral leukoplakia characterized by a high recurrence rate and high rate of transformation into oral squamous cell carcinoma. We present herein a case of PVL which was misdiagnosed as oral leukoplakia and progressed to oral carcinoma.

Keywords: Malignant, multifactorial, multifocal, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Leukoplakia is the most common premalignant, potentially malignant, or precancerous lesion of the oral mucosa. Leukoplakia is generally defined by as a predominantly white lesion of the oral mucosa that cannot be characterized as any other definable lesion.[1] Having a prevalence of 1.5%–4.3%, leukoplakia lesions exhibit varying clinical features of smooth or wrinkled surface and appearing as white or yellowish white patch. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) lesions have always been difficult to diagnose since their first description by Hansen et al.[2] Simple surgical excision of the PVL lesions almost always is followed by recurrence and ultimately malignant change.[3] Therefore, earlier recognition and early aggressive treatment may control the PVL lesion and improve the outcome. This case report discusses the factors that led to the incorrect diagnosis of this lesion.

CASE REPORT

A 38-year-old male patient reported to the department of periodontology with the complaint of whitish discoloration in the lower left back tooth region. The patient first noticed the discoloration 1 year back which gradually attained its present size in due course. Family and medical histories were noncontributory. The patient had a history of taking both smoke and smokeless tobacco for the past 17 years. The patient smoked 8–10 bidies per day. He used to chew gutkha once or twice daily on an occasional basis. Clinical examination revealed irregular keratotic growth on the gingival and alveolar mucosa extending anteroposteriorly from the mandibular right central incisor to the mandibular left second molar [Figures 1 and 2]. Growth was nontender, sessile, moderately firm in consistency, and without bleeding on provocation. On the basis of history and clinical examination, the lesion was diagnosed as oral leukoplakia. Surgical excision of the complete lesion was performed. A small portion of the lesion (0.8 cm × 0.5 cm) from a single site was sent for histological examination. Histopathology of the excised specimen revealed hyperkeratosis with few foci of mild dysplastic cells.

Figure 1.

Irregular keratotic growth involving gingiva and alveolar mucosa [anterior extension of growth]

Figure 2.

Irregular keratotic growth involving gingiva and alveolar mucosa [Posterior extension of growth]

The patient was followed up every 6 months. At 6-month follow-up, recurrence was observed on the marginal gingiva of the left mandibular first and second premolars [Figure 3]. Complete excision of the lesion was planned, but the patient denied treatment. At 1 year follow-up, no new recurrence or lesion was observed.

Figure 3.

Recurrence of the lesion over marginal gingiva of the mandibular left first and second premolars

One and half years after the surgery, another new recurrence was noticed on the gingiva in relation to the mandibular left lateral incisor and canine regions, with appearance similar to speckled type of leukoplakia [Figure 4]. Regional lymph nodes were not palpable. Panoramic radiographic view revealed no loss of bone in the regions of 32 and 33 [Figure 5]. The lesion was excised [Figure 6] and sent for histopathological examination. Histopathology revealed moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [Figure 7]. The periodic acid–Schiff-stained section confirmed the breach in continuity of basement membrane with few keratin pearls [Figure 8].

Figure 4.

New recurrence in relation to teeth number 32 and 33

Figure 5.

Panoramic radiographic view revealing no loss of bone in the regions of 32 and 33

Figure 6.

Excision of the lesion

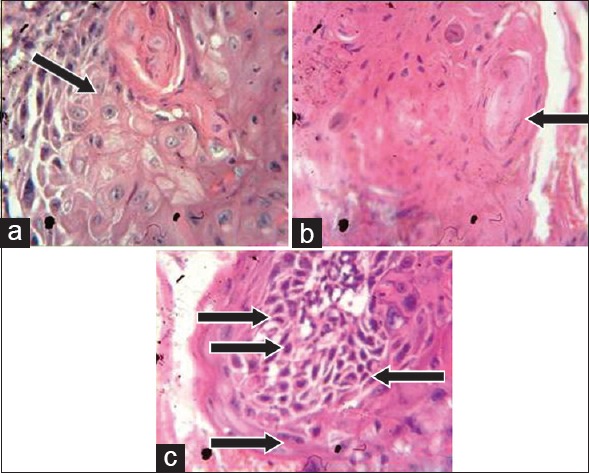

Figure 7.

(a) Histopathological section showing increased mitotic figures (×40); (b) presence of keratin pearls; (c) increased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, cellular pleomorphism, loss of cohesiveness, and hyperchromatic nuclei

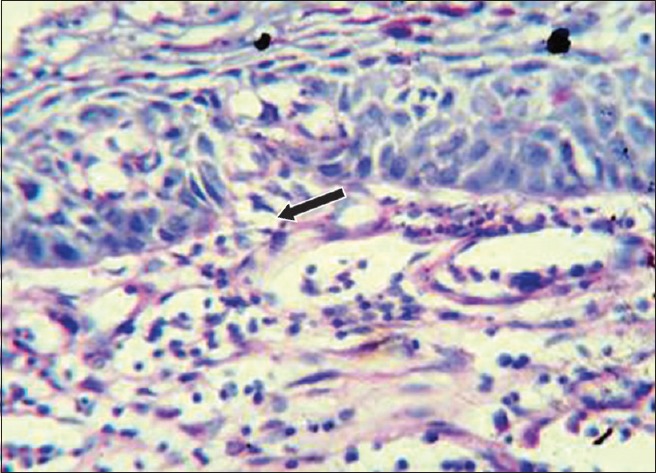

Figure 8.

The periodic acid–Schiff-stained section confirms the breach in continuity of basement membrane

DISCUSSION

SCC is the most common oral cancer comprising about 90% of all oral cavity cancers that may involve any oral site. Gingival involvement accounts for 6.3% of cases.[4] SCC can arise from normal-looking mucosa or from precancerous red, white, or mixed red and white lesions. Nearly 0.13%–17.5% of leukoplakic lesions transform into cancers, whereas PVL lesions progress to malignancies very frequently, indicating very high potential for uncontrolled growth.[5] Also known for high recurrence rate than conventional leukoplakia, the lesions of PVL do not respond to simple surgical excision and tend to recur, therefore early recognition and aggressive treatment is recommended to control the lesion and to prevent malignant change.[6] Recent reviews about the treatment of PVL show that PVL is unresponsive to almost all forms of excisional therapies, radiation, and chemotherapy.[7] Around 71.2% of recurrence rate after interventions with multiple approaches is indicative of recalcitrant nature of this entity.[8] Local block resection may limit the disease progression and stop recurrence, but sufficient evidence needs to be available to apply this extensive surgical modality.[9] The lesion in our patient recurred after surgical excision and progressed to carcinoma. Observing the aggressive and recurrent behavior and the potential of this lesion to become cancer, we changed the initial diagnosis to PVL.

Due to lack of experience and familiarity with these lesions, because PVL lesions are not common entities, and also similarity in the appearance of PVL lesions and oral leukoplakia, especially in the initial stages, clinicians usually make the diagnosis of leukoplakia (misdiagnosis) which leads to less aggressive treatment and ultimately recurrence and malignant change.[10] In majority of the studies, retrospective diagnosis of PVL has been reported.[2] Females are more frequently affected by PVL than males, with female-to-male ratio as high as 4:1.[8] A recent retrospective study by Borgna et al.[11] reports that males and females are affected by equal frequency with this lethal form of oral leukoplakia.

Despite advances in the molecular biology, the etiology of PVL still remains unknown. Multiple etiological factors are involved in the development of PVL lesions. For oral leukoplakia, tobacco is the major etiological factor, but available evidence reports that only few patients who develop PVL smoke.[10] The current literature reports that only 34.78% of patients diagnosed with PVL were smokers.[8] An unclear association with human papillomavirus has also been reported. Together, all these factors favored the diagnosis of nonhomogeneous leukoplakia of the present case.

Histopathology of PVL also varies differently, with areas exhibiting mild hyperkeratosis to areas showing dysplastic change even in one patient.[12] Absence of single defining histopathological feature warrants multiple biopsies that show some disease progression over time from simple hyperkeratosis to verrucous hyperplasia with or without dysplasia to verrucous carcinoma and finally SCC.[8] Therefore, any white lesion presenting as widespread growth should be biopsied from multiple sites. Due to lack of awareness and knowledge (specialty of the professional) about the varying histological changes that can be seen in the lesions of PVL, only a small portion of the lesion from the area of mandibular left premolars was sent for histopathology. Had we gone for the histological examination of the entire lesion or multiple biopsies from different sites, we could have obtained important clues.

Consistent with the location of the PVL in our case, mandibular gingiva is reported to be the most frequently involved site by the PVL.[5] PVL lesions are also seen on the buccal mucosa and tongue. Duration of 4.4–11.5 years is the time taken by the PVL to become malignant in majority of the studies reported.[13,14] In a systematic review by Abadie, 63.9% of PVL lesions turned into malignancy after a mean follow-up period of 7.4 years.[8] In contrast to the present case, Borgna et al. reported in a study that widespread gingival lesions had the lowest risk of malignant transformation compared to multifocal lesions of PVL. The lesion progressed to malignancy after about 1½ years in the present case. The reason for this early transformation is not known, but the possible role of genetic factors, aneuploidy, and p53 overexpression has been reported.

Another important finding was that SCC had already invaded the buccal bony plate (two-dimensional radiograph did not reveal bone loss) by the time it was first observed, suggestive of rapid invasion. Since the survival from SCC improves if the lesion is diagnosed before it invades,[4] it points out that clinicians should remain vigilant about certain features of white lesions indicative of malignant change. Patients with white lesions, especially widespread, need to be monitored at short-time intervals so that early changes can be detected. Treatment modalities for treating oral leukoplakias differ in their effectiveness, therefore patients should be followed up for evaluating response to treatment and to detect any recurrence and/or new growth. About 3–6-month follow-up interval for early premalignant lesions (mild-to-moderate epithelial dysplasia) has been reported, whereas lesions exhibiting severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ require early follow-ups.[15,16]

The present case report highlights the importance of timely and correct diagnosis of white lesions of the oral cavity which may look innocuous to the clinicians. Due to the resemblance of PVL lesions to leukoplakia and the absence of characteristic features, especially during early stage, and also the negative history of tobacco use in some cases, clinicians are faced with the challenge to correctly diagnose this variety of white lesions.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians should examine their patients carefully to inspect any potential precancerous lesions. If PVL lesions are not aggressively treated, they will recur and may progress to SCC or verrucous carcinoma. Unfortunately, many treatment modalities have proven ineffective in limiting the uncontrolled growth of PVL.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen LS, Olson JA, Silverman S., Jr Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:285–98. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salati NA. Clinic-pathologic evaluation and medical treatment of oral leukoplakia. Int J Pharm Sci Invent. 2014;3:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seoane J, Varela-Centelles PI, Walsh TF, Lopez-Cedrun JL, Vazquez I. Gingival squamous cell carcinoma: Diagnostic delay or rapid invasion? J Periodontol. 2006;77:1229–33. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandolfo S, Castellani R, Pentenero M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A potentially malignant disorder involving periodontal sites. J Periodontol. 2009;80:274–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghazali N, Bakri MM, Zain RB. Aggressive, multifocal oral verrucous leukoplakia: Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia or not? J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:383–92. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capella DL, Gonçalves JM, Abrantes AA, Grando LJ, Daniel FI. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Diagnosis, management and current advances. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;83:585–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abadie WM, Partington EJ, Fowler CB, Schmalbach CE. Optimal management of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A Systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:504–11. doi: 10.1177/0194599815586779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fettig A, Pogrel MA, Silverman S, Jr, Bramanti TE, Da Costa M, Regezi JA, et al. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:723–30. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.108950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phattarataratip E. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A literature review. CU Dent J. 2005;28:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgna SC, Clarke PT, Schache AG, Lowe D, Ho MW, McCarthy CE, et al. Management of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Justification for a conservative approach. Head Neck. 2017;39:1997–2003. doi: 10.1002/hed.24845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabay RJ, Morton TH, Jr, Epstein JB. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its progression to oral carcinoma: A review of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:255–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A follow-up study of 54 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:154–7. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagan JV, Jimenez Y, Sanchis JM, Poveda R, Milian MA, Murillo J, et al. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: High incidence of gingival squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:379–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodus NL, Kerr AR, Patel K. Oral cancer: Leukoplakia, premalignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58:315–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Cascarini L, McCaul JA, Kerawala CJ, Coombes D, Godden D, et al. How should we manage oral leukoplakia? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:377–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]