Abstract

Background:

Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP) arising from the mediastinal pleura may be confused with primary mediastinal tumors. We studied the computerized tomographic (CT) findings of patients with SFTP that could suggest a diagnosis of SFTP.

Materials and Methods:

At our hospital from January 1995 to June 2012, 39 patients with histologically confirmed SFTP were surgically treated; seven of them abutting the mediastinal pleura. The study group included seven patients aged between 53 and 81 years. Baseline CT scans were retrospectively reviewed to identify radiological findings suggestive of SFTP including: (1) smooth and sharply delineated contours; (2) obtuse, acute, or tapering angles between the lesion and the mediastinum depending on the size; (3) homogeneous soft-tissue attenuation; (4) “geographic pattern” due to the contemporary presence of large vessels, necrosis, and calcifications; (5) displacement of the lung parenchyma; (6) presence of a cleavage plane; and (7) absence of lymphadenopathy or pleural methastasis.

Results:

All tumors formed acute angles with the pleura. Six out of the seven presented smoothly tapering margins, three had a “geographic pattern” of attenuation and displaced the anterior junction line; one showed an outside junction line development. Four cases had a clear pleural origin.

Conclusions:

The possibility of SFTP should be taken into account when a mass abuts the mediastinum projecting inside the thoracic cavity in the presence of an intense and “geographical pattern” of enhancement without lymphoadenopathy or pleural metastasis. These findings assume greater significance in the presence of discrepancy between the size of the lesion and the clinical presentation.

KEY WORDS: Computed tomography, differential diagnosis mediastinum, mediastinal neoplasms, pleural tumors, solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura, thymic neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura (SFTP) are rare neoplasms originating from submesothelial primitive mesenchymal cells, unrelated to asbestos exposure, first described by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931.[1] Most of the tumors present as pleural-based masses but have also been reported in other locations including the mediastinum, lung, as well as in extrathoracic sites.[2,3,4] Although SFTP is usually benign, approximately 10%–20% are malignant or locally aggressive.[5] SFTP abutting the mediastinum can mimic primary mediastinal tumors.[6,7] The aim of this study was to evaluate retrospectively whether preoperative computed tomography (CT) could suggest the correct diagnosis a mediastinal SFTP and would like to emphasize the importance of considering SFTP in the differential diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 1995 and June 2012, 39 consecutive patients, between 40 and 81 years of age (average age, 64.9 years; median age, 68 years) underwent surgical resection for SFTP at our institution. Seven (18%) patients with a tumor abutting the mediastinum were identified.

The study group included four women and three men, aged 53-81 (mean 70) years. The symptoms dyspnea, and cough in three patients and hemoptysis in one case. Whereas other patients were asymptomatic. Surgical resection was complete in all patients and all had an uncomplicated postoperative outcome. Median follow-up was 40 months (range 3–78 months). Local recurrence of the tumor was recognized in the CT scan of one patient 57 months after surgery. Pleural location, type of surgery, and demographic data of the seven SFTP cases are presented in Table 1. CT scans, performed before surgical resection, were retrospectively reviewed.

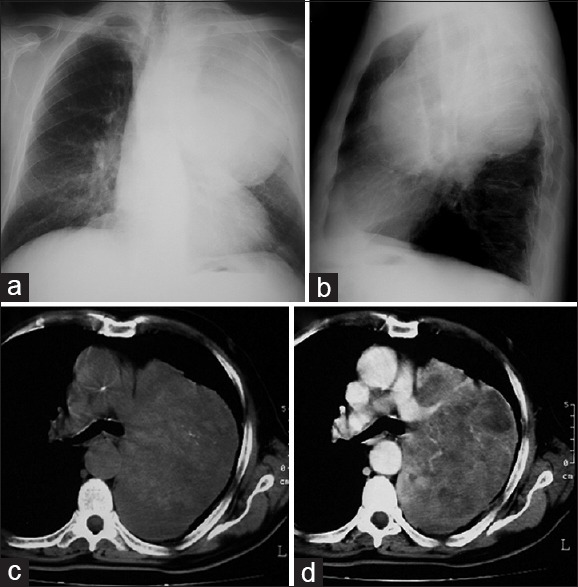

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of seven patients with SFTP abutting the mediastinum (LUL: left upper lobe, LLL: left lower lobe)

For each lesion, the CT features recorded included as follows: (1) relationship with mediastinal surface (type of angle forming to the adjacent pleura); (2) morphologic features and shape (lobulated, smooth or with ill-defined borders); (3) attenuation pattern (homogeneous, heterogeneous); (4) relationship with anterior junction line if present; (5) presence of a cleavage plane (fat plane between the tumor and adjacent mediastinal structures); (6) associated signs (lymphadenopathy or pleural metastasis).

Those tumors originating from paravertebral space were excluded from this study.

No lesion had lymphadenopathy or metastasis. In only three cases, multiplanar reformation (MPR) reconstruction was available. The characteristics that may help to differentiate putative origin of the mass are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics that may help to differentiate putative origin of the mass (interface lung-chest wall or lung-mediastinum)

RESULTS

Considering the relationship between the mass and the mediastinal surface, all the lesions showed acute angles, most of them (six out of seven) with smooth tapering margins. One lesion showed obtuse angles with the thymic compartment. All lesions presented well-defined, lobulated borders, and heterogeneous enhancement. In three out of six cases with heterogeneous enhancement, a typical “geographical pattern” was detected after contrast medium. A clear cleavage plane with mediastinal structures was not identifiable in four cases. In one case, we detected a mass effect on the anterior junction line. In another one, there was an outside junction line development without any shift. A pleural origin of the tumor was clearly visible in four of the seven cases.

The details of the characteristics of these lesions are as follows:

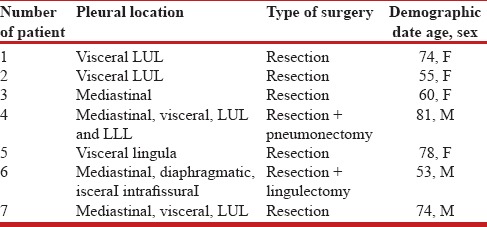

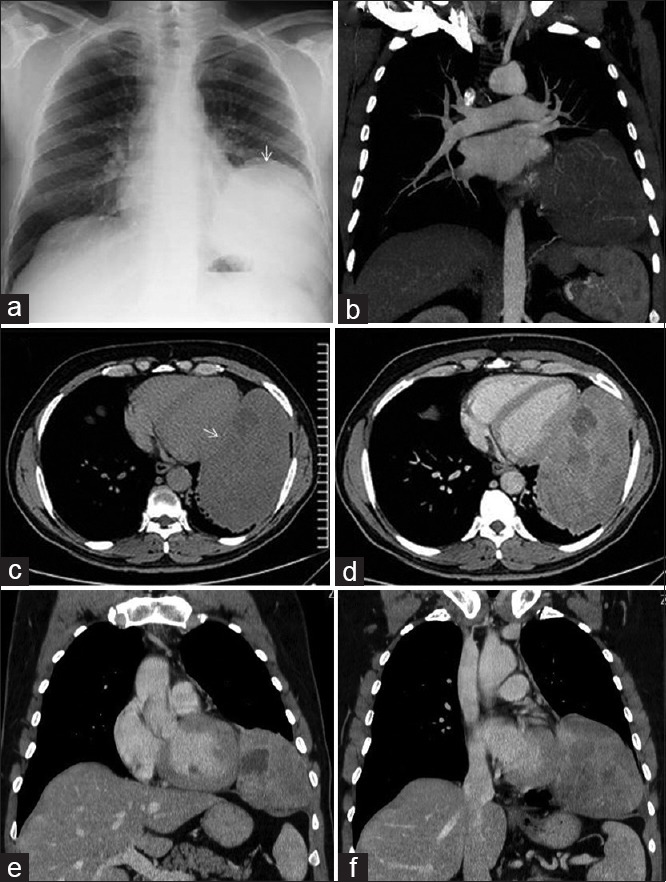

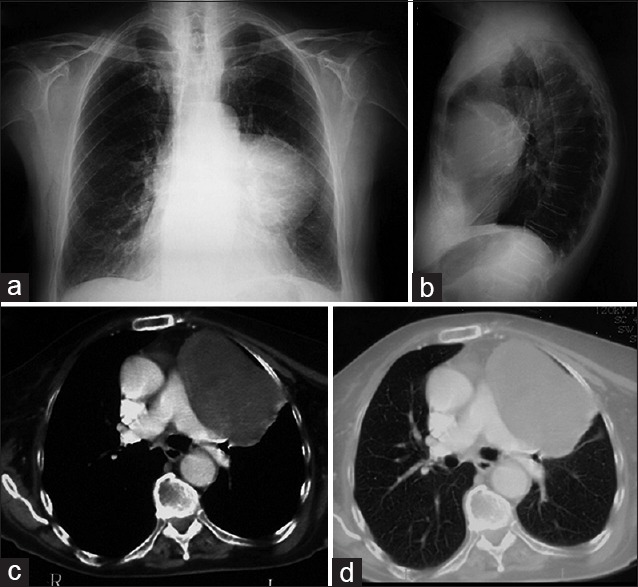

Patient No. 4 [Figure 1]: The large mass, at thoracotomy, was completely intra-pleural with well-defined margins closely adherent to the lung parenchyma. Despite the large size of the lesion, no mass effect was present at the level of the mediastinum. Another argument in favor of an SFTP is the “geographical pattern” after intravenous iodine contrast medium injection

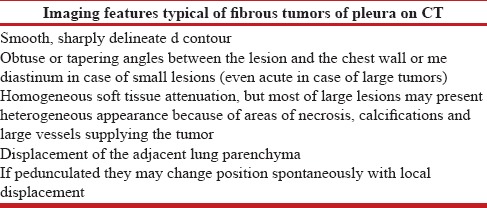

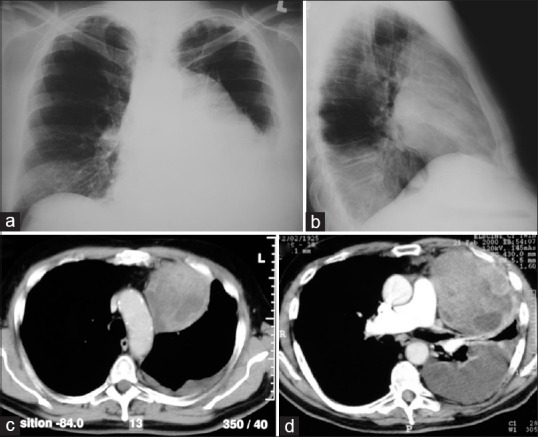

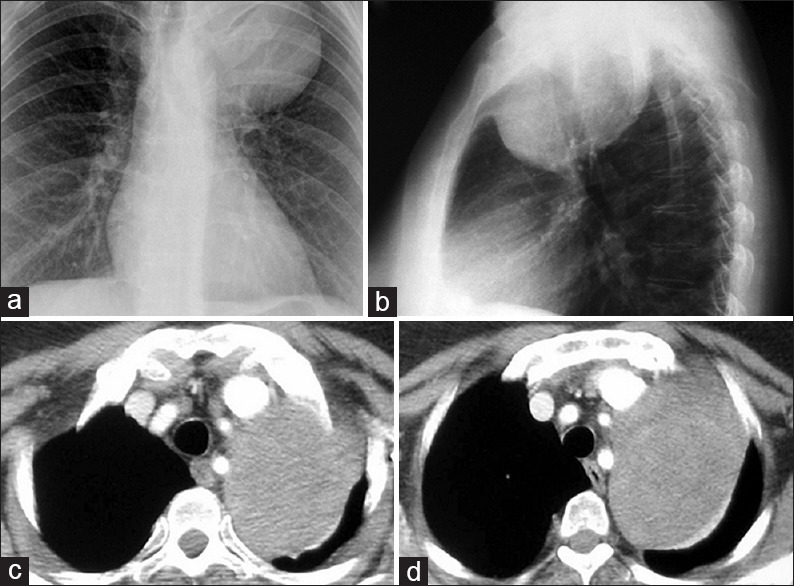

Patient No. 5 [Figure 2]: The mass, after left pleurotomy was performed, seemed to develop from the subpleural space, displaced in the opposite side the anterior junction line. This characteristic is suggestive of a pleural origin

Patient No. 6 [Figure 3]: In this paracardiac mass, a pedunculated thymoma as a potential differential diagnosis was considered. However, MPR reformation demonstrated the absence of any elongated pedicle starting from thymic compartment

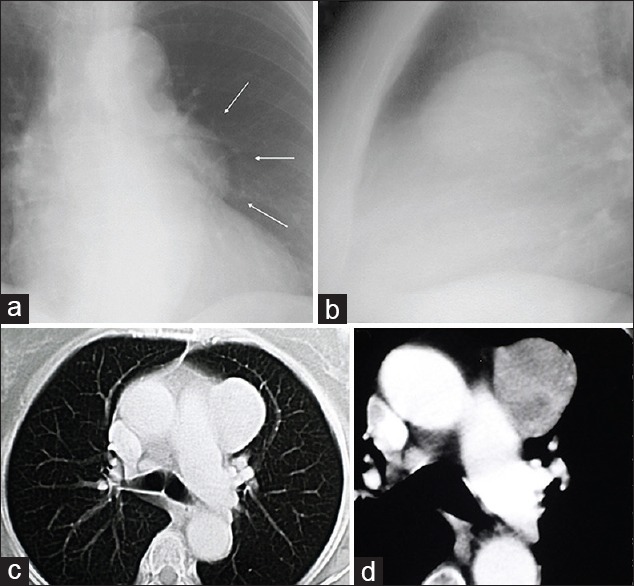

Patient No. 7 [Figure 4]: The mass was closely adherent to the superior lobe and to the lateral chest wall protruding deeply into the pleural cavity with a heterogeneous enhancement after intravenous iodine contrast medium injection. Table 3 summarizes the CT findings.

Figure 1.

An 81-year-old man with cough and dyspnea underwent chest radiographs which revealed a left upper lobe mass. The chest x-ray demonstrated a well defined large mass located in the left upper lobe which seemed adherent to the heart border (a and b). Computer tomography scans showed an intrathoracic large mass, with well-defined margins, without a cleavage plane with mediastinum and pulmonary artery (c and d). Despite the large size of the lesion no mass effect was present at the level of the mediastinum. Contrast-enhanced scans showed heterogeneous density with serpiginous branching linear areas of enhancement due to intralesional vessels, forming a “geographical pattern.” At thoracotomy the bulky lesion (15 cm in size) was occupying the whole left upper lobe and a portion of the lower and was characterized by nodules distributed deep down to the mediastinum. It was closely adherent to lung parenchyma. To obtain complete resection, left pneumonectomy was required

Figure 2.

A 55-year-old woman, with a history of total thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid carcinoma, underwent a routine chest X-ray (a and b) that demonstrated a well-defined oval-in-shape lesion located in the anterior mediastinal space (5 cm). Enhanced CT scan showed a well-defined mass, arising from the anterior mediastinum, with no signs of infiltration of adjacent structures, characterized by a subtle heterogeneous enhancement (c and d). The lesion was adherent to the superior mediastinum but seems displaces the anterior junction line to the opposite side compressing the superior mediastinum. Cervicotomy and manubriotomy with wedge resection showed that the lesion originated from the visceral pleura of mediastinal side of the left superior lobe. No lesion was found in the anterosuperior mediastinum. The left pleural cavity was opened and a pedunculated tumor arising from the visceral pleura of the left upper lobe was resected with a wedge resection of the lung

Figure 3.

A 53-year-old man presented with a history of several months of worsening dyspnea. A chest radiograph showed a mass with sharp margins located at the left pulmonary base (a). CT scans showed a large mass occupying the left inferior lobe, without a cleavage plane with the mediastinal profile, the chest wall and the diaphragm (c). Contrast-enhanced scans showed heterogeneous density of the lesion with central areas of low attenuation (b and d). Coronal reformation improves the topographical visualization of the mass and the relationship with the mediastinum showing an acute smoothly tapering margin (e and f). Left postero-lateral thoracotomy revealed a 18 cm pleural mass supplied by five vascular pedicles. The lesion originated from the mediastinal pleura in proximity of the phrenic nerve. At thoracotomy, the tumor presented as a lobulated mass, attached to the mediastinal pleura by several vascular pedicles. The pedicles were ligated and transected, and the tumor was removed from the left hemithorax

Figure 4.

A 74-year-old man with cough and respiratory distress. Chest X-ray showed an anterior bulky mass, located in the left superior lobe associated to pleural effusion (a and b). Chest CT demonstrated a lesion with heterogeneous like “mosaic” enhancement, in broad contact with the anterior junction line and chest wall, from which a clear cleavage plane cannot be identified; also a significant pleural effusion is present (c and d). Median sternotomy with excision was performed: the mass was closely adherent to the superior lobe and to the lateral chest wall, with macro and microscopic infiltration of mediastinal pleura and lung parenchyma. It was not possible to establish with certainty the origin from visceral or parietal pleura. En bloc extrapleural resection of the mass with a wedge resection of the lung was performed.

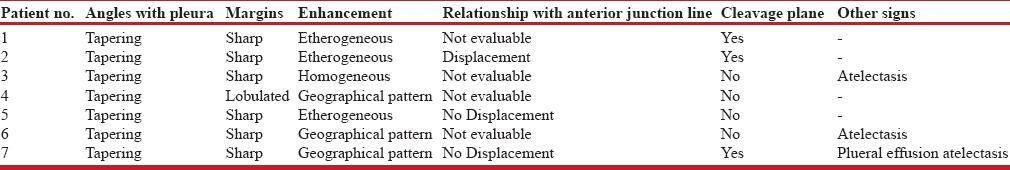

Table 3.

Summary of CT findings of the examined lesions

DISCUSSION

It is important to note that a mass, arising from the mediastinal surface, developing in the pleural cavity, presenting regular margins, without evidence of any mass effect on mediastinal structures should be regarded as having a high probability of pleural or pulmonary origin. Furthermore, a lesion abutting the anterior junction line with contralateral displacement, must be considered as starting from the border between the lung and mediastinum, i.e., from the pleura.

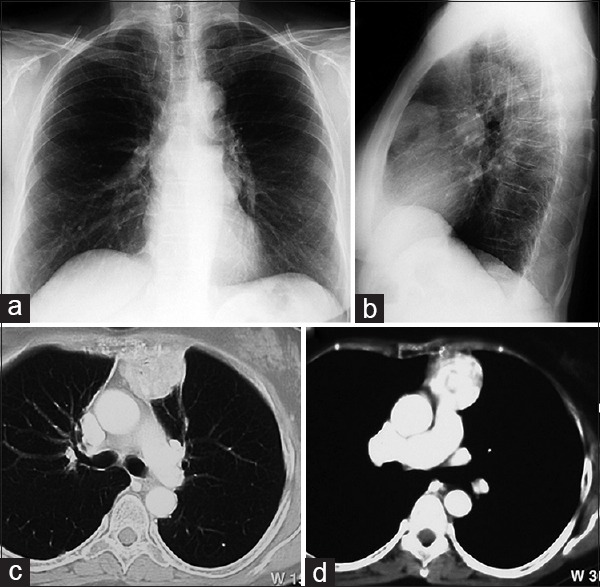

Small SFTP usually appears as homogeneous, well-defined, noninvasive, lobular, soft-tissue masses which abut the pleural surface and may form obtuse angles against adjacent pleura surfaces.

Large tumors appear as heterogeneous soft tissue masses and form an acute angle with the pleura surface with smoothly tapering margins.[4,5,6,7,8,9] The finding of an acute smoothly tapering margin seems to be a more reliable sign of the pleural origin of the larger masses, as reported by Briselli et al.[8] The enhancement of large lesions is typically intense and heterogeneous following a “geographical pattern” with areas of low attenuation, which have been shown to correlate with: myxoid change, hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystic degeneration and areas of enhancement containing serpiginous branching linear hyperdensities consistent with intralesional vessels.[3,4,9,10,11,12] In this study, our goal was to identify the characteristics when SFTP develops from mediastinal pleura. Imaging features, such as location and relationships to adjacent structures, are extremely useful for making a preliminary evaluation about the putative origin of the tumor, highlighting the difficulties of choosing an appropriate surgical approach.

SFTPs that arise from mediastinal pleura can easily resemble a mediastinal tumor[13] and often radiological findings may not allow differential diagnosis [Figures 5-7]. Indeed, according to Mendelson et al.,[14] the possibility of SFTP should be considered in the differential diagnosis when lesions abut the mediastinum, in addition to as thymic neoplasms, dysembriogenetic tumors, or lymphomas. The interface of the lung-chest wall or lung-mediastinum affects the growth of the lesion and can indicate the origin between pleural, mediastinal, and lung masses [Table 2].

Figure 5.

A 74-year-old woman presented with a 2-month history of episodic blood streaking of the sputum. Chest radiographs (a and b) showed a well-defined, homogeneous density opacity projecting anterior the left hilum (arrows in a). CT scans demonstrated a 5.5 x 4.2 x 4 cm mass with well-delineated lobular contour abutting the mediastinal surface (c). After the administration of intravenous contrast material, CT scans showed moderately heterogeneous enhancement of the mass (d). During surgery, a segmental resection of the left upper lobe revealed a 48-gram pedunculated mass, originated from the visceral pleura

Figure 7.

A 78-year-old woman with fever underwent a chest X-ray that showed a large opacity localized in the retro-sternal space (a and b). Enhanced CT scans demonstrated a well-defined round lesion (10 x 9 cm), heterogeneous, without signs of infiltration of mediastinum which occupies part of the thymic lodge extending in the pleural cavity (c and d). Left lateral thoracotomy with wedge resection was performed; the large mass was pedunculated, growing up from the lingular visceral pleura.

Figure 6.

A 60-year-old woman underwent routine health screening examinations. Chest radiographs showed a well-defined, rounded mass occupying the left pulmonary apex without a cleavage plane with the mediastinum (a and b). CT scans in c demonstrated a large lesion (11 x 8 cm) arising from the mediastinum, in contact with aorta and epiaortic vessels protruding in the upper lung cavity forming a smooth tapering angle with the mediastinal pleura characterized by a very subtle heterogeneous enhancement (d). Left upper lobectomy was performed: the lesion was growing up from the mediastinal pleura with strict adherence with lung parenchyma close to the origin of the subclavian artery. At thoracotomy, the mass presented as a lobulated tumor arising from the mediastinal pleura and densely adhering to the left upper lobe. To achieve complete resection, a lobectomy of the upper lobe was required

A lung mass forms acute angles against adjacent pleural surfaces while pleural and mediastinal lesions appear as masses with their maximum diameter abutting the mediastinal pleural surface: These lesions form obtuse, straight, or acute angles but with tapering connecting angles.[5,10]

True mediastinal lesions open wide the “anterior junction line” producing asymmetric/symmetric bulging of the lateral boundaries which are a key factor that can help in differential diagnosis.

On the contrary, pleural lesions usually displace the anterior junction line medially. Sometimes, this is not very evident because the anterior mediastinal space maintains its normal appearance [Figure 2].

Relating to the contrast medium, all mediastinal tumors as thymic neoplasms, disembriogenetic tumors or lymphomas may show cystic or necrotic degeneration with heterogeneous enhancement not allowing a differential diagnosis on radiologic appearances alone.[15,16,17]

A challenge regarding the interpretation of chest imaging is some thymomas that grow outside the mediastinum inside the pleural cavity. Although originating inside the thymic lodge, they demonstrate the appearance of “intrapleural growing mass.” This happens for a migration of thymic tissue along the pericardium, under the parietal pleura (also defined as “pedunculated thymoma”).[18,19] These tissues may present as masses completely located in the thoracic cavity still connected to the anterosuperior mediastinum by a pedicle.[18,19] One possible explanation of this is that it is due to anatomical features of the anterior mediastinal compartment limited on the one side by the sternocostal plan and on the other by heart and large vessels. For this reason, some thymomas tend to grow inside the thoracic cavity where the pressure is less.

Typical thymomas are closely related to the superior pericardium that is anterior to the aorta, main pulmonary artery, and the superior vena cava. The tumor is usually well-defined, round, or lobulated, homogenous and enhances after contrast injection.[20,21,22,23]

Nevertheless, it can be heterogeneous, or even cystic because of areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.[20,21,22,23] The tumor can be partially or completely outlined by fat and may contain punctuate course, or curvilinear calcifications.[20,21,22,23] The analysis of our cases shows that most of the lesions have some features that can suggest the possibility of a pleural mass on the basis of CT findings. For the other lesions, radiological findings are unspecific and cannot allow differentiation from true mediastinal masses. Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for SFTP. The choice of the operative approach is driven by location, size, and putative origin (pleural, pulmonary, or mediastinal) of the mass as well as by the surgeon's preference.

Indeed, three-dimensional CT angiography has been shown to be a valuable adjunct for treatment planning and safe resection in patients with large tumors by accurately delineating the blood supply and identifying the origin of the tumor.[24]

One limitation of our study was the retrospective analysis. Other methodological limitations were the limited number of patients (note that the neoplasms in itself are not frequent) and the use of equipment which in some cases was not the most recent technology.

CONCLUSIONS

SFTP can be a diagnostic challenge for radiologists, because, CT findings may not allow differentiation from a mediastinal lesion. The possibility of SFTP should be taken into consideration when there is a mass abutting the mediastinum projecting completely inside the pleural cavity without lymphadenopathy or pleural metastasis and in the presence of intense and heterogeneous enhancement following a “geographical pattern.”

The use of MPR reconstruction is mandatory to evaluate the relationship between the mass and the mediastinal lines.

This possibility is more significant in the presence of a discrepancy between the size of the lesion and the clinical presentation without lymphadenopathy or pleural metastasis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klemperer P, Coleman BR. Primary neoplasms of the pleura. A report of five cases. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22:1–31. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanau CA, Miettinen M. Solitary fibrous tumor: Histological and immunohistochemical spectrum of benign and malignant variants presenting at different sites. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:440–9. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Perrot M, Fischer S, Bründler MA, Sekine Y, Keshavjee S. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:285–93. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardinale L, Allasia M, Ardissone F, Borasio P, Familiari U, Lausi P, et al. CT features of solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura: Experience in 26 patients. Radiol Med. 2006;111:640–50. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0062-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Abbott GF, McAdams HP, Franks TJ, Galvin JR. From the archives of the AFIP: Localized fibrous tumor of the pleura. Radiographics. 2003;23:759–83. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardinale L, Cortese G, Familiari U, Perna M, Solitro F, Fava C, et al. Fibrous tumour of the pleura (SFTP): A proteiform disease. Clinical, histological and atypical radiological patterns selected among our cases. Radiol Med. 2009;114:204–15. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luciano C, Francesco A, Giovanni V, Federica S, Cesare F. CT signs, patterns and differential diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. J Thorac Dis. 2010;2:21–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briselli M, Mark EJ, Dickersin GR. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: Eight new cases and review of 360 cases in the literature. Cancer. 1981;47:2678–89. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810601)47:11<2678::aid-cncr2820471126>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dedrick CG, McLoud TC, Shepard JA, Shipley RT. Computed tomography of localized pleural mesothelioma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:275–80. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferretti GR, Chiles C, Choplin RH, Coulomb M. Localized benign fibrous tumors of the pleura. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:683–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.3.9275877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chick JF, Chauhan NR, Madan R. Solitary fibrous tumors of the thorax: Nomenclature, epidemiology, radiologic and pathologic findings, differential diagnoses, and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:W238–48. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu X, Zhang L, Xue Z, Ren Z, Sun YE, Wang M, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: An analysis of forty patients. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:146–54. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.01.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yashiro T, Shiba M, Sato K, Matsuzaki O, Iizasa T, Otsuji M, et al. Huge localized fibrous tumor of the pleura resembling a mediastinal tumor: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:58–61. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendelson DS, Meary E, Buy JN, Pigeau I, Kirschner PA. Localized fibrous pleural mesothelioma: CT findings. Clin Imaging. 1991;15:105–8. doi: 10.1016/0899-7071(91)90156-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juanpere S, Cañete N, Ortuño P, Martínez S, Sanchez G, Bernado L, et al. Adiagnostic approach to the mediastinal masses. Insights Imaging. 2013;4:29–52. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santana L, Givica A, Camacho C Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Best cases from the AFIP: Thymoma. Radiographics. 2002;22:S95–102. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc12s95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suehisa H, Yamashita M, Komori E, Sawada S, Teramoto N. Solitary fibrous tumor of the mediastinum. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:205–8. doi: 10.1007/s11748-009-0510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fava C, Maggi G. Radiological diagnosis of thymoma: Consideration on 52 cases (author's transl) Radiol Med. 1977;63:527–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan IL, Swayne LC, Widmann WD, Wolff M. CT demonstration of “ectopic” thymoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1988;12:1037–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198811000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marom EM. Imaging thymoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:S296–303. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f209ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Restrepo CS, Pandit M, Rojas IC, Villamil MA, Gordillo H, Lemos D, et al. Imaging findings of expansile lesions of the thymus. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2005;34:22–34. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priola AM, Priola SM, Di Franco M, Cataldi A, Durando S, Fava C, et al. Computed tomography and thymoma: Distinctive findings in invasive and noninvasive thymoma and predictive features of recurrence. Radiol Med. 2010;115:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Priola AM, Priola SM, Cardinale L, Cataldi A, Fava C. The anterior mediastinum: Diseases. Radiol Med. 2006;111:312–42. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usami N, Iwano S, Yokoi K. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: Evaluation of the origin with 3D CT angiography. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:1124–5. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815ba277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]