In this issue of AJPH, an article published by He et al. (p. 241) highlights the issue of hearing loss and low rates of hearing aid use in older adults in China, a condition that receives little attention around the world and particularly in East Asian and developing countries. The authors demonstrate that rates of hearing aid use among those who could benefit is 6.5%, which is far lower than rates observed in countries such as the United States and Australia and throughout Western Europe.

OBJECTIVE AUDIOLOGICAL TESTING

The investigators are to be commended for the rigor of their study, which involved an initial cohort of over 45 000 individuals recruited at 144 sites throughout China, who then had objective audiological testing using established World Health Organization (WHO) protocols. All too often, epidemiological studies of hearing rely solely on self-report questions, which can lead to vastly different reported rates of “hearing loss” in the literature. However, even those studies using objective audiological assessments often use disparate definitions of hearing loss based on different frequencies, threshold values, and reference ear (better ear, worse ear, or average of both) rather than established WHO definitions, as were used in this study. Likewise, inexpensive yet rigorous methods to objectively measure hearing in the field without the need of a sound booth or specialized equipment are also now possible with tablets and smartphones. These approaches, coupled with applying standardized protocols for measuring and defining hearing, have the potential to vastly improve our public health understanding of hearing loss.

HEARING AND DEMENTIA

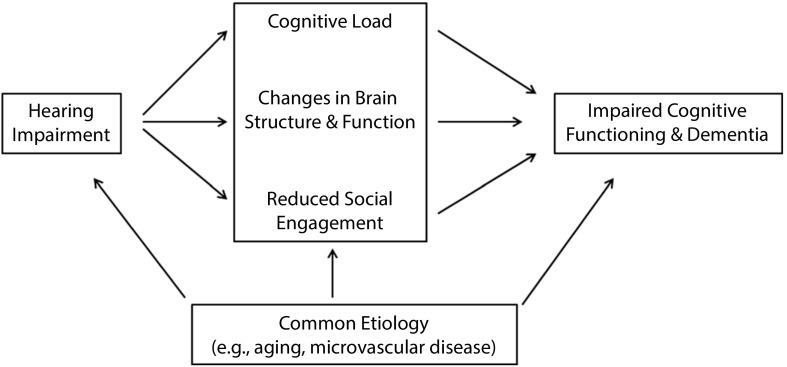

A broader question pertains to the public health relevance of addressing hearing loss compared with other chronic conditions that affect older adults. Given its high prevalence, hearing loss is often perceived as an unfortunate but relatively inconsequential aspect of aging, despite hearing serving as the foundation for nearly all daily activities (e.g., our ability to effortlessly talk to friends and family, listen to TV and music). Epidemiological research over the past several years has begun to overturn this perception, with studies demonstrating independent associations of hearing loss with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia, health care costs, falls, and other critical health outcomes. Importantly, causal pathways may underlie these observed associations, suggesting that hearing interventions could potentially lower the risk of these outcomes. For example, mechanisms underlying the associations between hearing and dementia include cognitive load from impoverished auditory encoding by the cochlea, reduced auditory stimulation contributing to faster brain atrophy, and social isolation (Figure 1).1 Indeed, a convened Lancet commission report on dementia released in July 2017 concluded that among all known risk factors for dementia, hearing loss is the single modifiable risk factor carrying the greatest population-attributable risk, exceeding the risk conferred individually by hypertension and other factors.2 An ongoing, large-scale randomized controlled trial—The ACHIEVE (Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders) Study, sponsored by the National Institute on Aging—will definitively determine whether treating hearing loss in older adults reduces the risk of cognitive decline and dementia (clinicaltrials.gov; identifier: NCT03243422).

FIGURE 1—

Conceptual Model of Hypothesized Mechanistic Pathways Linking Hearing Loss With Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Older Adults

CURRENT BARRIERS TO UPTAKE OF HEARING CARE

As in other epidemiological studies of hearing aid uptake, He et al. investigated potential reasons for not using a hearing aid. Importantly, these issues must be considered in the broader context of the multiple barriers (affordability, accessibility, awareness, and technology design) that currently limit uptake of hearing care.

Affordability: regulations in most countries specify that hearing aids can only be sold by a licensed provider; as a result, hearing aid costs are often bundled together with the provider’s time and services for programming the hearing aids, which may not always be needed. Consequently, the average cost for hearing aids is approximately $47003 and could represent the third largest material purchase in life for many Americans, after a house and a car.

Accessibility: hearing aid provision and other related services remain clinic based, and individuals with hearing loss (nearly two thirds of all adults aged 70 years or older) must make repeated trips to a clinician simply to obtain a hearing aid, irrespective of the severity or complexity of their hearing loss.

Awareness and understanding: health providers and individuals in society are poorly informed or lack knowledge about the manifestations and consequences of hearing loss or how to access hearing care.

Hearing technology design and utility: more than 95% of the world hearing aid market is controlled by six hearing aid companies, thereby limiting the pace of innovation. For example, hearing aid features such as connectivity with smartphones and rechargeable batteries are all considered features to be sold at a higher cost despite these features being introduced long ago. By contrast, in any analogous consumer technology field (e.g., smartphones), innovative new features are often sold at a premium initially but then quickly become standard features within a matter of months.

ADDRESSING BARRIERS TO HEARING CARE

Systematically addressing these barriers requires a top-down approach. In the United States, a cascade of national initiatives to confront the barriers that limit broader uptake of hearing care has followed in the wake of epidemiological research linking hearing with dementia and other adverse outcomes in older adults. The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) published a report on hearing loss in October 2015,4 which was then followed by the National Academies convening a consensus study from 2015 to 20163 to provide recommendations on how to improve the accessibility and affordability of hearing care for adults. A key recommendation of both the PCAST and National Academies reports was for the Food and Drug Administration to create a new regulatory classification for over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids. This recommendation resulted in the introduction of bipartisan legislation (OTC Hearing Aid Act of 2017; HR 1652, S. 670), which was passed by Congress and signed into law in August 2017 and will mandate OTC hearing aids by 2020. The availability of such devices (which will allow for companies such as Samsung, Apple, and Bose to begin selling hearing aids) has substantive ramifications for access to hearing care. OTC devices could potentially reduce all four barriers to hearing care simultaneously through lowering costs, improving access, and bringing higher-profile visibility and functionality to hearing aids with consumer technology integration. Importantly, availability of these devices would leverage market forces and the innovations that are happening at lightning speed in the consumer technology industry to fundamentally shift how hearing care is perceived, accessed, and delivered.

RESILIENCE AND SUCCESSFUL AGING

Public health progress over the past century that has contributed to greater life expectancy around the world can broadly be attributed to overcoming the era of infectious disease at the beginning of the 20th century and, now, to increasing control of chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis and hypertension. As we move forward, public health advances to improve the lives of older adults need increasingly to also focus on approaches to promote resilience and successful aging. Efforts to enhance the ability of older adults to remain socially engaged and reduce the functional impact of hearing loss hold substantive potential to improve the lives of older adults and potentially to reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes such as dementia. However, reducing the multiple barriers to hearing care will require a concerted top-down approach and joint efforts across researchers, industry, and policymakers, as evidenced by recent efforts in the United States leading to the passage of federal legislation for OTC hearing aids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author received funding from the National Institutes of Health (grants R01AG055426, R33DC015062, U01HL096812, and P30AG048773) and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation. He is a consultant to Cochlear and Amplfon.

Footnotes

See also He et al., p. 241.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin FR, Albert M. Hearing loss and dementia—who is listening? Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(6):671–673. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liverman C, Domnitz S, editors. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Hearing Health Care: Priorities for Improving Access and Affordability. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Aging America & Hearing Loss: Imperative of Improved Hearing Technologies. 2015. Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST/pcast_hearing_tech_letterreport_final.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2017.