Abstract

In vivo evaluation of [18F]BMS-754807 binding in mice and rats using microPET and biodistribution methods is described herein. The radioligand shows consistent binding characteristics, in vivo, in both species. Early time frames of the microPET images and time activity curves of brain indicate poor penetration of the tracer across the blood brain barrier (BBB) in both species. However, microPET experiments in mice and rats show high binding of the radioligand outside the brain to heart, pancreas and muscle, the organs known for higher expression of IGF1R/1R. Biodistribution analysis 2 h after injection of [18F]BMS-754807 in rats show negligible [18F]defluorination as reflected by the low bone uptake and clearance from blood. Overall, the data indicate that [18F]BMS-754807 can potentially be a radiotracer for the quantification of IGF1R/IR outside the brain using PET.

Keywords: IGF1R, IR, Insulin, Radiotracer, MicroPET

The insulin like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) is a member of the class of tyrosine kinase receptors (TKR), binds endogenous growth hormones such as insulin like growth factors 1 and 2 (IGF-1 and IGF-2) and IGF binding protein (IGF-BP).1–4 Drugs that block IGF1R can treat cancers, metabolic disorders, endocrine disorders, and possibly a variety of neurodegenerative disorders.5–11 IGF1R is overexpressed in malignant tissues where it has an antiapoptotic effect by enhancing cell survival, growth and anabolic effects.1–3 Noninvasive in vivo imaging methods have the potential for early detection and monitor progression of diseases, and response during therapy. Noninvasive Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging of the IGF1R can both quantify IGF1R binding during illness and its occupancy by therapeutic antagonists.

To date, five major classes of ligands have been evaluated for IGF1R imaging, including proteins, antibodies, peptides, affibodies and small molecule-based TKRI ligands. Initial molecular imaging studies were performed with 125I-radiolabeled IGF-I and its truncated analogues using SPECT.12,13 However, due to high protein binding, in vivo de-iodination and rapid clearance from normal tissues, these ligands are not effective imaging agents of IGF1R. In vivo imaging of 111In labeled synthetic IGF1R (E3R) in breast cancer xenograft tumor mouse model using SPECT shows good tumor contrast and a strong linear correlation of IGF1R expression levels with tracer uptake in vivo.14 R1507, a well studied IGF1R monoclonal antibody (mAB) in human, was radiolabeled with SPECT and PET isotopes (111In, and 89Zr) and tested in tumor model.15–18 Tumor uptake was higher for 111In-R1507 and 89Zr-R1507 in comparison to that of 125I-R1507. 111In-R1507 SPECT has also been utilized to predict the response to anti-IGF1R therapy in human bone sarcoma xenografts.18 Although, antibody-based imaging is successful in mouse models, its research and clinical usefulness is limited by slow kinetics and poor target/non-target contrast due to the level of expression of IGF1R in normal tissues. There have been unsuccessful attempts to image IGF1R antibodies with quantum dots.19 IGF1R based protein nucleic acids (PNA) conjugated with 64Cu and 99mTc were tested in IGF1R overexpressing breast cancer xenografts in mice.20,21 A few radioligands based on IGF1R selective affibodies have been labeled with 111In and they showed modest tumor uptake and tumor-to-blood ratio.22 However, 64Cu labeled IGF1R affibodies showed better tumor to tissue ratios in gliomas and prostate cancer xenografts.23 Although some of the ligands listed above showed promise for imaging IGF1R binding, these molecules do not cross the BBB due to their polar nature and are limited to imaging outside the brain. Evaluation of potential therapeutic compounds that bind to IGF1R in brain requires development and testing of selective non-peptide PET ligands with high receptor affinity and selectivity and adequate lipophilicity. TKR inhibitors of IGF1R are suitable candidates for PET radioligands for in vivo imaging. We screened many TKRIs for this purpose and selected BMS-754807, a small molecule dual inhibitor of IGF1R/IR (IC50 = <2 nM),24,25 in phase III clinical trials for a variety of human cancers, as one of the candidate ligands for imaging using PET.26–29 BMS-754807 also exhibit significant affinity to MET (IC50 = 5.6 nM), ALK (IC50 = 5.7 nM) AurA (IC50 = 9 nM), TrkA (IC50 = 7.4 nM) and TrkB (IC50 = 4.1 nM), however shows >100 fold selectivity over various other kinases.24 Cellular growth and receptor autophosphorylation studies showed a higher selectivity BMS-754807 over MEK and TrkA and TrkB.24,33 We synthesized [18F] BMS-754807, measured its logP as 2.8 and tested the proof of concept of IGF1R imaging in surgically removed and pathologically identified grade IV-glioblastoma, breast cancer and pancreatic tumor using autoradiography (see Fig. 1).30 To the best of our knowledge [18F]BMS-754807 is the only small molecule radiotracer candidate reported so far for imaging IGF1R that has been derived from TKRIs. Subsequently, we evaluated the potential of [18F]BMS-754807 for in vivo imaging and the findings in rats and mice with microPET and biodistribution are described here.

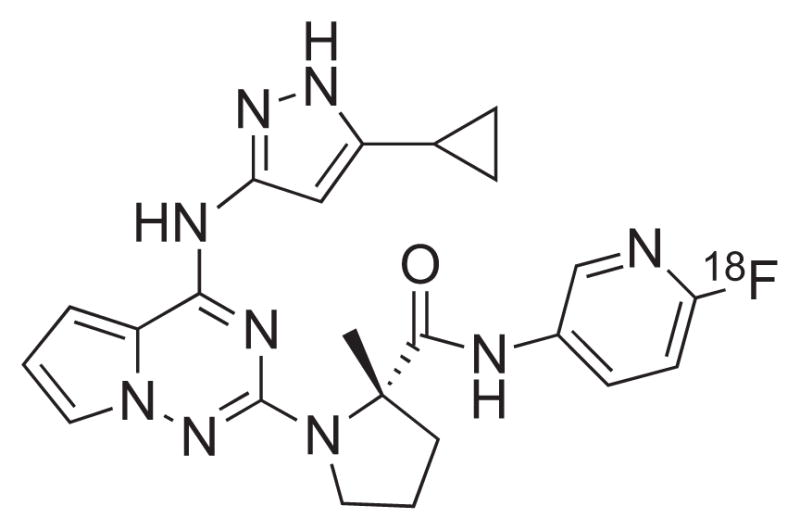

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of [18F]BMS-754807.

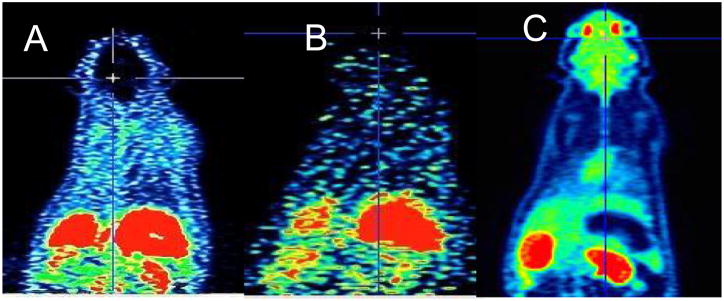

Synthesis of the reference standard BMS-754807 and its precursor and radiosynthesis of [18F]BMS-754807 are accomplished by our previously reported procedure.30 Briefly, [18F]BMS-754807 was obtained in 8 ± 4% yield with >95% radiochemical purity and 2 ± 0.5 Ci/μmol specific activity (N = 6). The radioproduct was formulated in 5% ethanol and normal saline solution and filtered through a 0.22 μm sterile filter into a sterile vial for further studies. MicroPET imaging of [18F]BMS-754807 (200 ± 50 μCi, 200 μL) was performed in anesthetized male Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 2) and C57BL/6 mice (N = 2) using Inveon microPET camera (Siemens).31 Our initial focus was to test the in vivo potential of [18F]BMS-754807 to image brain IGF1R/IR levels in rodents. The radioactivity in the early time frame (1–10 min, Fig. 2A) and the later time frame (81–90 min, Fig. 2B) of the microPET images in rats show that the radioligand accumulation is negligible in brain, in contrast to the uptake of [18F]FDG (Fig. 2C) in brain. This negligible uptake in the brain may be attributed to lack of sufficient IGF1R in control brain or likely due to rapid efflux of [18F]BMS-754807 by p-GP/MDR.

Fig. 2.

Representative rat microPET coronal images of [18F]BMS-754807 (A and B) and [18F]FDG (C). A: Sum of 0–10 min; B: sum of 81–90 min; C: sum of 0–10 min.

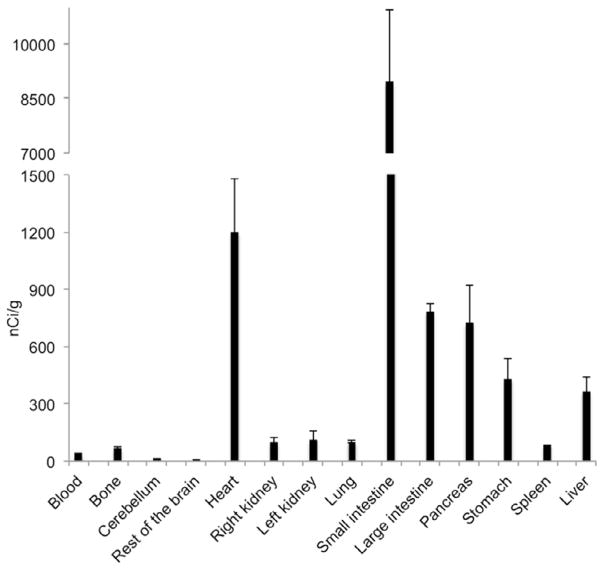

We performed biodistribution studies of [18F]BMS-754807 in rats 120 min post injection (Fig. 3) and observed low levels of radioactivity in brain. The radioligand had largely cleared from blood at 120 min and minimal formation of [18F]fluoride via defluorination of radiotracer was observed as evident by no bone uptake (Fig. 3). There was significant uptake of the radiotracer in heart and pancreas. The unusually higher uptake of [18F]BMS-754807 in small intestine, and moderate uptake in large intestine and liver may be due to possible radioactive metabolites. We found low binding of [18F]BMS-754807 in stomach and negligible binding in spleen, lung and kidneys in biodistribution experiments.

Fig. 3.

Average biodistribution of [18F]BMS-754807 in rats at 120 min.

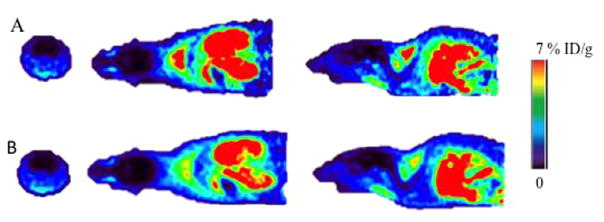

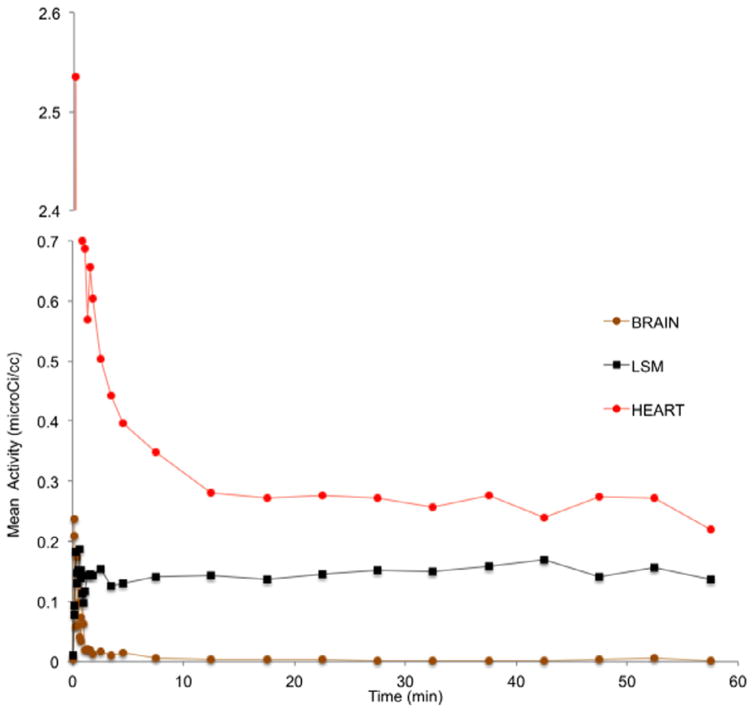

Next, we examined the in vivo binding of [18F]BMS-754807 in mice with microPET. Consistent with the results obtained in rats, there was no noticeable brain activity of the radiotracer in mice (Fig. 4). Time activity curves did not support an initial influx of the radiotracer into brain (see Fig. 5). The brain level of activity peaked at less than 1 min post-injection followed by fast washout. Typically, radiotracers that cross the BBB show the highest signal in brain around 2–4 min, followed by quick washout if there is insufficient binding sites in brain. High uptake of [18F]BMS-754807 was observed in heart and muscles of mice, the organs known for high expression of IGF1R/IR (see Fig. 5).2 The binding of [18F]BMS-754807 in mouse is consistent with the results of rat microPET and biodistribution experiments.

Fig. 4.

Sum of 0–10 min (A) and 0–60 min (B) microPET images of [18F]BMS-754807 in a representative mouse. First column: Axial; second column: Coronal; third column: Transaxial.

Fig. 5.

Time activity curves of [18F]BMS-754807 in a representative mouse (brain; LSM: lymph skeletal muscle; THA: thalamus).

In summary, microPET studies of [18F]BMS-754807 in rats and mice showed significant binding to heart and pancreas, where IGF1R is known to be present. The radioligand exhibited negligible brain uptake in both species, possibly due to a pGP/MDR effect or due to lack of sufficient amount of IGF1R proteins in control animals to be detectable by PET. We also like to cite the human protein atlas here, which shows very low score for IGF1R protein expression in brain.32 In a recent report, BMS-754807 did not show significant survival benefit in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPGs) mice models due to the low drug concentration in tumor. Pharmacokinetic analysis also demonstrates low concentration of BMS-754807 in tumor tissue suggesting poor BBB permeability likely due to pGP/MDR inhibition of drug.33 However, we found 5.25 times higher binding of [18F]BMS-754807 in grade IV glioblastoma (GBM) in comparison to control brain tissues by autoradiography method. 30 Therefore, imaging experiments in disease rodent models where IGF1R is overexpressed such as GBM or other neurological disorders may confirm the potential of [18F]BMS-754807 to detect brain IGF1R when tumor BBB is compromised. Ex vivo biodistribution studies also support the results of microPET imaging with lack of sufficient brain radioactivity, limited [18F]defluorination and minimal accumulation of [18F]BMS-754807 in blood in rats. Biodistribution experiments showed the binding of the radioligand in heart and pancreas where IGF1R/IR is known to be present, consistent with the microPET images. Furthermore, since [18F] BMS-754807 shows high uptake in heart, pancreas and muscle, it might not be amenable for imaging breast and pancreatic cancer. However, this tracer may be useful for imaging metabolic, endocrine disorders. Future experiments such as in vivo competition assays, radiometabolite analyses with arterial input functions and imaging studies in rodent disease models would demonstrate the suitability of [18F]BMS-754807 as a PET imaging agent for IGF1R/IR in normal and pathological conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Health grant R01 CA160700 (W.P.).

References

- 1.Maki RG. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4985–4995. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yee D, editor. Insulin-like Growth Factors. IOS Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conover CA. Endocr J. 1996:S43–S48. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.43.suppl_s43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foulstone E, Prince S, Zaccheo O, et al. J Pathol. 2005;205:145–153. doi: 10.1002/path.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gualberto A, Pollak M. Oncogene. 2009;28:3009–3021. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeRoith, editor. Insulin-line Growth Factors and Cancer: From Basic Biology to Therapeutics. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yee D. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2012;104:975–981. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duarte AI, Moreira PI, Oliveira PRJ. J Aging Res. 2012:384017. doi: 10.1155/2012/384017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moll L, Zemva J, Schubert M. Role of central insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signalling in ageing and endocrine regulation. In: Akin F, editor. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology Up-to-Date. InTech; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aleman IT. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41:395–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freude S, Schilbach K, Schubert M. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:213–223. doi: 10.2174/156720509788486527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun BF, Kobayashi H, Le N, et al. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:318–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun BF, Kobayashi H, Le N, et al. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2754–2759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Cai W. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2012;2:248–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelissen B, McLarty K, Kersemans V, Reilly RM. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heskamp S, van Laarhoven HW, Molkenboer-Kuenen JD, et al. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1565–1572. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.075648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleuren ED, Versleijen-Jonkers YM, van de Luijtgaarden AC, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7693–7703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.England CJ, Kamkaew A, Im HJ, et al. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:958–966. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H, Zeng X, Li Q, Gaillard-Kelly M, Wagner CR, Yee D. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:71–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian X, Aruva MR, Zhang K, et al. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1699–1707. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian X, Aruva MR, Qin W, et al. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:2070–2082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolmachev V, Malmberg J, Hofstrom C, et al. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:90–97. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.090829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xinhui S, Kai C, Yang L, Xiang H, Shuxian M, Zhen C. Amino Acids. 2015;47:1409–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-1975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carboni JM, Wittman M, Yang Z, et al. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3341–3349. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wittman MD, Carboni JM, Yang Z, et al. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7360–7363. doi: 10.1021/jm900786r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King ER, Wong KK. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2012;7:14–30. doi: 10.2174/157489212798357930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halvorson KG, Barton KL, Schroeder K, et al. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scagliotti GV, Novello S. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franks SE, Jones RA, Briah R, Murray P, Moorehead RA. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:134. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1919-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majo VJ, Arango V, Simpson NR, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:4191–4194. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.microPET biodistribution studies of [18F]BMS-754807 in rodents: All animal handling and experimental procedures were performed under an IACUC approved protocol of The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Northshore-LIJ and Vanderbilt University). MicroPET imaging of [18F]BMS-754807 were performed in anesthetized male Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 2) and C57BL/6 mice (N = 2) using Inveon microPET camera (Siemens). Transmission scans were acquired with 68germanium point source and used attenuation correction. [18F]BMS-754807 (0.2 ± 0.05 mCi) was injected into the tail vein and initiated camera acquisition. List-mode data were collected 90 min for rats and 60 min for mice and reconstructed using attenuation correction and Fourier rebinning. The dynamic images were reconstructed using a filtered back-projection algorithm and interpolated to give nCi/cc (microPET Manager, Inveon Microsystems Inc.). The regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn on the PET images. Time activity curves were generated for ROIs including heart, muscles and brain. Biodistribution studies were performed in the same rats (N = 2) at 2 h after the microPET scanning. Briefly, the rats were decapitated and organs were removed (brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidney, spleen, small intestine, bone and blood etc) and serum half-life were calculated as percentages of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g tissue). Tracer uptakes in the tissues were measured using a γ-counter and expressed nCi/g.

- 32.http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000140443-IGF1R/tissue.

- 33.Halvorson KG, Barton KE, Schroeder K, et al. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]