Abstract

Background

COPD assessment test (CAT) is a short, easy-to-complete health status tool that has been incorporated into the multidimensional assessment of COPD in order to guide therapy; therefore, it is important to understand the factors determining CAT scores.

Methods

This is a post hoc analysis of a cross-sectional, observational study conducted in respiratory medicine departments and primary care centers in Spain with the aim of identifying the factors determining CAT scores, focusing particularly on the cognitive status measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and levels of depression measured by the short Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Results

A total of 684 COPD patients were analyzed; 84.1% were men, the mean age of patients was 68.7 years, and the mean forced expiratory volume in 1 second (%) was 55.1%. Mean CAT score was 21.8. CAT scores correlated with the MMSE score (Pearson’s coefficient r=−0.371) and the BDI (r=0.620), both p<0.001. In the multivariate analysis, the usual COPD severity variables (age, dyspnea, lung function, and comorbidity) together with MMSE and BDI scores were significantly associated with CAT scores and explained 45% of the variability. However, a model including only MMSE and BDI scores explained up to 40% and BDI alone explained 38% of the CAT variance.

Conclusion

CAT scores are associated with clinical variables of severity of COPD. However, cognitive status and, in particular, the level of depression explain a larger percentage of the variance in the CAT scores than the usual COPD clinical severity variables.

Keywords: COPD, CAT, Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE, Beck Depression Inventory, BDI

Introduction

COPD assessment test (CAT) is a short, easy-to-complete health status tool that has been developed to help patients and their clinicians assess and quantify the symptoms and impact of COPD and enable better communication between patients and physicians about the consequences of the disease.1 The CAT has demonstrated its reliability and validity in quantifying disease states in COPD and correlates strongly with other measures of COPD-specific health-related quality of life, such as the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.1–3 In addition, the CAT score is a good predictor of the risk of exacerbation,4 of outcomes during and after exacerbations,5,6 and even of the risk of death.7

The Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has incorporated the CAT score into the multidimensional assessment of COPD and the algorithm of pharmacologic treatment of COPD as a measure of symptom intensity, together with the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale.8 There is some debate about the use of either CAT or mMRC to classify patients into low and high symptom levels because several studies have argued that the classification of a given patient may differ according to the scale used.7,9 In addition, it is important to understand the factors determining CAT scores because some of them, such as comorbidities, may not be influenced by specific COPD medications.10

In this study, we have analyzed data from a large population of patients with COPD enrolled in primary care and specialized clinics in order to investigate the determinants of the CAT scores, paying special attention to the impact of cognitive status and depression. The results may help the clinician in the interpretation of CAT results and their impact on the therapeutic management of the disease.

Methods

Study population, design, and assessments

This is a secondary analysis of a cross-sectional, observational study conducted in respiratory medicine departments and primary care centers in Spain, aimed at investigating the prevalence and impact of depression in COPD.11 The study population comprised ambulatory COPD patients who were at least 40 years of age, current or former smokers of at least 10 pack-years, and had stable disease (confirmed by post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] <0.7 and absence of exacerbations in the previous 3 months). All patients who correctly completed the assessments of quality of life, depression, and cognitive function were included in the current analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain) and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed the written informed consent form before inclusion in the study.

Investigators recorded patients’ sociodemographic data and clinical information, including post-bronchodilator spirometric parameters and history of exacerbations. COPD severity was evaluated by the mMRC dyspnea scale12 and the BODEx (Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exacerbations) index,13 whereas comorbidity was rated by the Charlson index.14 Physical activity was measured by patients’ self-reported average minutes walked every weekday, as previously described.15

CAT questionnaire

The CAT is a disease-specific questionnaire to assess the health status in individuals with COPD. The questionnaire consists of eight items: cough, expectoration, dyspnea, chest tightness, going up hills/stairs, confidence leaving home, activity limitations at home, quality of sleep, and levels of energy, each presented on a five-point scale, providing a total score of 0 (floor) to 40 (ceiling), indicating the impact of the disease.1,2 When one or two items are missing, their scores can be set to the average of the non-missing scores; when more than two responses are missing in the CAT, a score cannot be calculated.1,2 We used the validated Spanish version of the CAT.1

Measurement of depressive and cognitive status

Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the short Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). This tool is a 13-item, self-administered questionnaire that evaluates affective, cognitive, motivational, and vegetative symptoms of depression; items are rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (extreme form of each symptom).16 We used the established cutoff points for stratifying depression severity: 0–4= no depression, 5–7= mild depression, 8–15= moderate depression, and >15= severe depression.17

Cognitive status was assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),18,19 which is widely used to screen for cognitive impairment. This instrument explores spatial and temporal orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, language, and visual construction in 12 items and 30 questions. The correct answer to a question scores 1 point (total from 0 to 30). A score <27 indicates cognitive impairment.20

Statistical analysis

CAT scores of 0–10, 11–20, 21–30, and 31–40 were defined for mild, moderate, severe, and very severe clinical impact, respectively. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and SD. Categorical values are described as absolute and relative frequencies. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of qualitative variables, whereas the analysis of variance test was used to determine the relationship between quantitative variables by group. Univariate associations between CAT scores and MMSE and BDI scores were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Stepwise forward multiple regression analyses were performed to examine the relative contributions of different variables to the CAT score. In order to establish the contribution of the neuropsychiatric condition, a first model was developed with CAT score as the dependent variable and depression and cognitive status as the only independent variables (Model 1), together and by each variable. Model 2 also included relevant demographic and clinical variables such as age, sex, post-bronchodilator FEV1 (%), history of exacerbations (dichotomized as yes/no according to the presence of any exacerbation the previous year), dyspnea, and comorbidity as independent variables. Model 3 was developed with a stepwise automatic selection of variables with a p-value <0.15. Finally, the independent contribution of post-bronchodilator FEV1 (%) and FEV1/FVC of CAT variance was also calculated. p-values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 Service Pack 3 software.

Results

Sample characteristics and distribution by CAT score

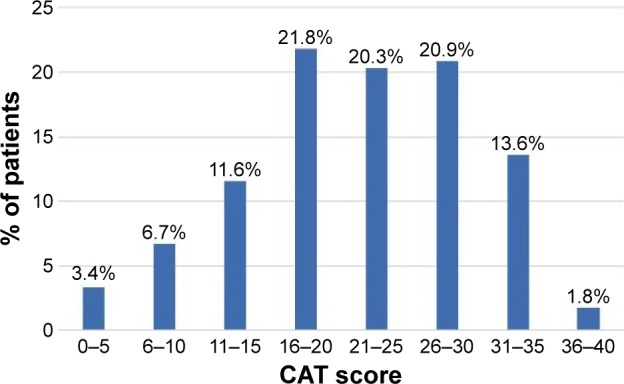

A total of 1,273 patients were screened, of whom 372 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria (6 were younger than 40 years, 48 were never smokers or smoked <10 pack-years, 146 did not provide spirometry, 148 did not have airflow obstruction, and 24 had severe cognitive impairment). Of the remaining 901 patients, 684 (76%) provided complete data for all the requested questionnaires and were considered valid for the analysis. Baseline characteristics of the patients with or without completed questionnaires were not significantly different (data not shown). Mean age was 68.7 years (SD =9.3 years), and 570 (84.1%) patients were men. The mean CAT score was 21.8 (SD =8.6), and 57% had a CAT score >20. Distribution of CAT scores by five-point intervals is presented in Figure 1. Patients in primary care had a worse mean CAT score compared with patients in specialized care (23.2 [SD =7] versus 20.5 [SD =8.5], p<0.001), despite showing a better mean FEV1 (%) (54.7% [SD =17.2%] versus 51.3% [SD =16.6%], p=0.017). Patients with higher CAT scores were significantly older, had longer COPD duration, poorer lung function and more severe dyspnea, presented more frequent exacerbations in the preceding year, and more often received domiciliary oxygen therapy. Similarly, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and comorbidity burden were significantly higher in patients with higher CAT scores (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of CAT scores among participants.

Abbreviation: CAT, COPD assessment test.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

| Variable | CAT score category

|

All (N=684) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10 (n=69) | 11–20 (n=228) | 21–30 (n=282) | 31–40 (n=105) | ||

| Age (years) | 65.8±10.5 | 68.7±9.4 | 69.5±9.1* | 68.8±8.9 | 68.7±9.3 |

| Sex (men) | 57 (82.6) | 197 (87.6) | 227 (81.4) | 89 (85.8) | 570 (84.1) |

| Active smoker | 16 (23.2) | 44 (19.5) | 60 (21.6) | 25 (24.3) | 145 (21.4) |

| COPD duration (years) | 7.6±6.2 | 10.1±7.6 | 12.1±6.6 | 15.8±9.4*** | 11.5±7.7 |

| FVC (mL) | 3,291±824 | 2,959±883 | 2,812±927 | 2,858±994*** | 2,917±922 |

| FVC (%) | 78.5±16.9 | 69.8±16.1 | 69.2±17.4 | 68.4±18.1*** | 70.2±17.2 |

| FEV1 (mL) | 1,876±616 | 1,725±739 | 1,630±719 | 1,619±759*** | 1,685±725 |

| FEV1 (%) | 58.0±15.3 | 53.5±15.8 | 51.4±16.6 | 48.6±17.5*** | 52.3±16.3 |

| FEV1/FVC | 56.5±11.8 | 55.8±11.2 | 53.5±12.3 | 53.0±13.8** | 5.5±12.2 |

| Cough (yes) | 34 (49.3) | 171 (76.7) | 255 (91.7) | 102 (97.1)*** | 562 (83.3) |

| Expectoration (yes) | 30 (43.5) | 137 (62.0) | 222 (89.4) | 93 (89.4)*** | 482 (72.3) |

| Dyspnea (yes) | 56 (81.2) | 220 (96.5) | 279 (99.6) | 105 (100)*** | 660 (96.8) |

| Exacerbations in the previous year (yes) | 47 (68.1) | 192 (84.2) | 268 (95.0) | 91 (86.7)*** | 598 (87.4) |

| Oxygen therapy at home (yes) | 3 (4.6) | 29 (13.4) | 87 (32.0) | 39 (40.2)*** | 158 (24.3) |

| BODEx | 1.4±1.4 | 2.2±1.5 | 3.4±1.8 | 4.2±1.6*** | 3.0±1.9 |

| MMSE | 28.8±1.8 | 27.0±3.5 | 25.7±4.0 | 23.9±5.7*** | 26.2±4.2 |

| BDI score | 3.5±3.3 | 6.0±3.9 | 10.8±5.5 | 14.4±7.4*** | 9.0±6.2 |

| Depression (yes) | 18 (26.1) | 142 (62.3) | 255 (90.4) | 101 (96.2)*** | 516 (75.4) |

| Severe depression (yes) | 1 (1.4) | 9 (3.9) | 54 (19.1) | 40 (38.1)*** | 104 (15.2) |

| Charlson index | 0.8±1.1 | 1.0±1.0 | 1.6±1.4 | 2.4±2.0*** | 1.4±1.4 |

| Minutes walked per day | 78.4±39.3 | 69.9±49.8 | 56.9±41.5 | 40.8±29.8*** | 61.2±44.2 |

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Differences in age were significant for the comparison between CAT 0–10 and CAT 21–30, p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 (Fisher’s test or ANOVA).

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BODEx, body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exacerbations; CAT, COPD assessment test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Depressive and cognitive status and correlations with CAT scores

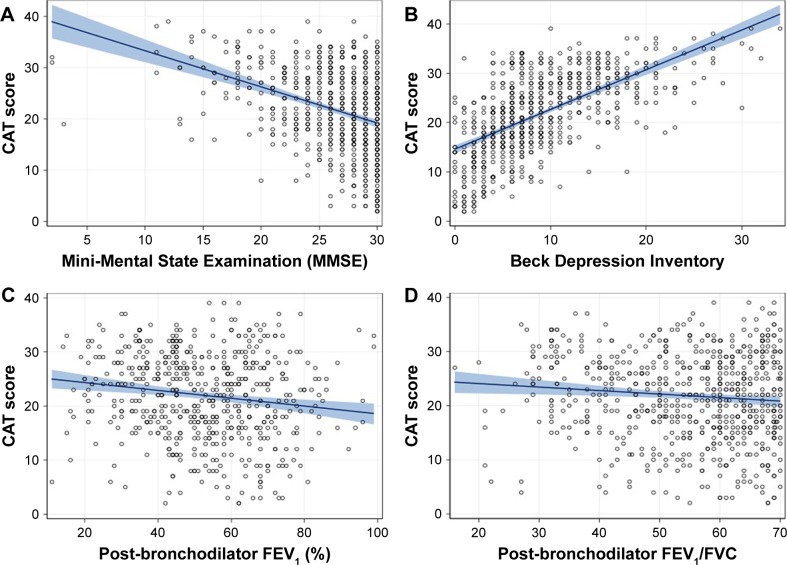

Global mean MMSE and BDI scores were 26.2 (SD =4.2) and 9.0 (SD =6.2), respectively. A total of 516 patients (75.4%) had some degree of depression, and 104 (20.2%) had severe depression. Correlations of the CAT score with MMSE score, BDI score, FEV1 (%), and FEV1/FVC are depicted in Figure 2. The CAT score correlated significantly with the MMSE score (Pearson’s r coefficient =−0.371, p<0.0001) and the BDI score (r=0.620, p<0.0001). Both FEV1 (%) and FEV1/FVC also correlated significantly with the CAT score, with Pearson’s r values of −0.151 and −0.100 (both p<0.001), respectively. All items of CAT correlated significantly with the BDI scores, with “having energy” showing the strongest correlation (r=0.59, p<0.0001), followed by “confidence leaving the house” (r=0.57, p<0.0001) and “chest tightness” showing the weakest correlation (r=0.37, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Correlation between CAT score and MMSE scores (A), BDI scores (B), post-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted) (C), and post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC (D).

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CAT, COPD assessment test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Factors associated with CAT scores – multivariate analysis

In the multivariate analysis, Model 1 showed that both cognitive status and depression were associated with the CAT score, with a good fit of the model (p<0.001) and explained 40% of the full variance of CAT score (Table 2). Model 2, which also included the most relevant demographic and clinical variables, explained 43% of the CAT variance, although several variables emerged as not significantly related with CAT score. Model 3 with a stepwise automatic selection of variables – MMSE score, BDI score, post-bronchodilator FVC (%), post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC, degree of dyspnea, and Charlson Index – explained nearly 45% of the CAT full variance (Table 2). When the variables were tested independently, MMSE score alone explained almost 14% of the CAT variance and BDI score alone explained 38% of it. In contrast, FEV1 (%) alone explained 2% of the CAT score variance, whereas FEV1/FVC explained 1% of it (Table 3).

Table 2.

Multivariate regression analysis for CAT score variance

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI score | 0.73 (0.04)*** | 0.65 (0.04)*** | 0.68 (0.05)*** |

| MMSE score | −0.23 (0.06)*** | −0.14 (0.06) | −0.13 (0.07)* |

| Age | 0.006 (0.02) | −0.07 (0.03)** | |

| Sex | −0.31 (0.66) | ||

| Post-bronchodilator | NA | −0.06 (0.02)*** | |

| FVC (%) | |||

| Post-bronchodilator | −0.03 (0.02) | ||

| FEV1 (%) | |||

| Post-bronchodilator | NA | −0.9 (0.02)*** | |

| FEV1/FVC | |||

| Dyspnea | −6.90 (1.35)*** | −6.60 (1.44)*** | |

| Previous exacerbations | −1.20 (0.72) | ||

| Charlson index | 0.66 (0.18)** | 0.60 (0.20)** | |

| r2 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.45 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Notes: Data are presented as beta value (SE).

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001. Model 1 only includes BDI and MMSE scores; Model 2 includes the whole set of variables, except FVC and FEV1/FVC due to collinearity; Model 3 stepwise automatic selection of variables with a p-value <0.15.

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CAT, COPD assessment test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NA, not assessed; SE, standard error.

Table 3.

Univariate regression analysis for CAT score variance

| Variable | Beta value (SE) | r2 |

|---|---|---|

| BDI score | 0.80 (0.04)*** | 0.38 |

| BODEx | 2.06 (0.15)*** | 0.23 |

| MMSE score | −0.70 (0.07)*** | 0.14 |

| Charlson index | 1.99 (0.19)*** | 0.13 |

| Minutes walked per day | −0.04 (0.007)*** | 0.07 |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1 (%) | −0.07 (0.02)*** | 0.02 |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | −0.07 (0.02)** | 0.01 |

Note:

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BODEx, body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exacerbations; CAT, COPD assessment test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SE, standard error.

Discussion

The CAT questionnaire is a very useful tool for quantifying the impact of COPD in patients with this disease.1,9 It was designed as a simple questionnaire that can be used in everyday clinical practice to understand the health status of patients and facilitate communication between patients and physicians.1 Due to its excellent psychometric characteristics and its predictive value for different outcomes in COPD, the GOLD has incorporated the CAT score into the algorithm of pharmacologic treatment of COPD as a measure of symptom intensity, together with the mMRC dyspnea scale.8 However, the CAT is more than a scale of intensity of symptoms; CAT scores correlate very well with the scores of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, the most widely used disease-specific, health-related quality of life questionnaire in COPD,1,21 suggesting that this tool provides information that goes beyond the level of symptoms.

The multivariate model developed with all the study variables demonstrated the association of CAT scores with the usual characteristics of COPD severity (age, lung function impairment, degree of dyspnea, and comorbidity) and with the MMSE and BDI scores. This model explained up to 45% of CAT variability. However, a model including only MMSE and BDI scores explained 40% and the BDI alone explained 38% of CAT variability.

The relationship between CAT scores and depression has been demonstrated in previous studies. Lee et al,22 in a study of 803 patients with COPD, using the patient health questionnaire-9 to assess depressive symptoms found a significant correlation between both questionnaires (r=0.631, p<0.001) and that the patient health questionnaire-9 score explained 45% of the variance of CAT. Morishita-Katsu et al,21 in a study on 109 patients with COPD, found a correlation coefficient of 0.464 between CAT and the depression score of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), even higher than −0.393 found between CAT and the 6-minute walk distance. In a stepwise multiple regression analysis, only depression in HADS and baseline dyspnea index were significantly associated with CAT scores and together explained 36% of the variance.21 Similarly, Dodd et al23 found a correlation coefficient between HADS depression score and CAT of 0.36 among 261 COPD patients included in a rehabilitation program. Finally, another study in Japan with 336 COPD patients found a significant association between CAT and depressive symptoms on HADS (HADS depression score ≥11); other comorbidities significantly associated with CAT scores were gastroesophageal reflux disease, arrhythmia, and anxiety.10 It is interesting to compare the correlation observed between CAT scores and scores of the depression questionnaires (0.620 in our study and between 0.36 and 0.63 in other publications, depending on the population and the questionnaires used) with those observed between CAT and COPD-specific physiologic measures, such as FEV1 (−0.15 in our study and between −0.17 and −0.23 in other large studies).1,23,24

The relationship between CAT and depression has also been investigated in a small case–control study in patients with COPD and mild hypoxemia. As in our study, the authors used the BDI and found a similar correlation between BDI and CAT in their selected population (r=0.56, p<0.00001). The BDI score alone explained 31% of the variance of CAT, and a cutoff of 20 units identified major depression with an odds ratio of 7.88.25

Models developed to try to identify demographic and clinical determinants of CAT scores have provided reasonably consistent results. Models including mMRC dyspnea scale, exacerbations rate/year, and either FEV1 (% predicted) or total lung capacity (% predicted) explained 36% of the CAT variance.9 The prediction of CAT scores at COPD diagnosis was associated with post-bronchodilator FEV1 and exacerbations/year with an r2 of 0.49.26 Similarly, our best model had an r2 of 0.45, but interestingly, the model including only the MMSE and BDI had already an r2 of 0.40.

The isolated impact of cognitive status on health status is not so clear. In our population, the relationship between cognitive status and CAT scores was weaker than that observed for depression. However, it was stronger than the association between CAT scores and spirometric parameters. Several studies using different methods to evaluate cognitive status did not find an impaired health-related quality of life associated with increased cognitive impairment,27–30 although only one used the CAT to evaluate quality of life.30 In a previous analysis of our population, we found a prevalence of cognitive impairment of 39.4%, and this impairment was significantly associated with lower educational level and impaired generic health-related quality of life measured by the EuroQol-5 dimensions questionnaire. CAT scores were not significant in the multivariate analysis, probably due to collinearity with the EuroQol-5 dimensions scores. In the univariate analysis, patients with cognitive impairment had significantly worse CAT scores (25.2 [SD =6.9] versus 19.3 [SD =8.7], p<0.001).31 It is important to point out that patients with severe cognitive impairment that prevents them from understanding and completing the questionnaires were not included in the study.

The CAT questionnaire was developed to provide clinicians and patients with a simple and reliable measure of overall COPD-related health status for the assessment and long-term follow-up of individual patients; however, the GOLD strategy uses the CAT threshold of 10 units to differentiate patients into groups A, C or B, D, and as such, to guide the need to step up or step down COPD treatment. Although CAT scores are predictive of most COPD outcomes, it is important to be aware of the strong association between CAT scores and depression in order to make the appropriate conclusions and take the right course of action.

Our study has some limitations; since spirometry was not one of the main outcomes of the study, no formal validation of spirometric values was conducted beyond the elimination of those values that were out of range or inconsistent. The results presented here are derived from a post hoc analysis of the original study,11 and finally, the majority of patients included were men, consistent with the epidemiological characteristics of COPD in Spain,32,33 and therefore, extrapolation of these results to women must be made with caution.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate the strong association between CAT scores and depression in COPD patients. Since the CAT is proposed as a tool to guide pharmacologic treatment in COPD, this association must be taken into account to help make the right therapeutic decisions in daily practice.

Acknowledgments

The DEPREPOC study has been funded by Grupo Ferrer (Barcelona, Spain). The authors would like to acknowledge the role of Saned (Barcelona, Spain) in monitoring of the study and statistical analysis of data, and the participation of the following investigators in the DEPREPOC study: Ada Luz Andreu, Adolfo García Molné, Ahmad Khalaf Ayash, Alberto Saura Vinuesa, Alejandra Marín Arguedas, Alejandro García Huete, Alejandro Muñoz Fernández, Alfons Torrego Fernández, Alfonso Van Der Eynde Collado, Alfredo González Panizo, Alfredo Pérez Cortada, Alicia Catalán Salelles, Alicia Marín Tapia, Alicia Taboada Duro, Alvaro Ortega Gutierrez, Alvaro Pérez Gómez, Amin Shubbi Shehebar, Amparo Alaban Ibáñez, Ana Boldova Loscertales, Ana Fortuna Gutierrez, Ana Luisa Kersul, Andrés Huete Martos, Andres Sánchez Barón, Angel Lara Font, Angels Puigdollers Rovellat, Antoni Riba Blanch, Antonio Bosquet Álamo, Antonio Camps Selles, Antonio Cuesta Sánchez, Antonio Hernández Ruiz, Antonio Pablo Arenas Vacas, Antonio Rodríguez Celaya, Antonio Tafalla Martín, Antonio Torras Picón, Armand Izquierdo Martínez, Bassam Darwich Muhti, Benigno Del Busto De Lorenzo, Berta Avilés Huertos, Carlos A Aguado Hernández, Carlos Martín Carrasco, Carlos Martínez Rivera, Carlos Millan Sánchez, Carme Santiveri Gilabert, Carmen Soto Fernández, Casimir Money Sánchez, Ceferino Pico López, Celedonio Sobera Echezarreta, Cesar Vidal González, Cesáreo López Rodríguez, Claudio Vidal De Mesa, Concepción Pérez Domínguez, Concepción Plans Bolibar, Concepción Rodríguez Fernández, Dámaso Escribano Sevillamo, David Blanques Escribano, David Herrero I Barrera, David Orts Giménez, Demetrio González Vergara, Deopatria Esteban Fresno, Diego Ferrer Marín-Blazquez, Domingo Fernández García, Eloy López Neira, Emilio Viudes Plazas, Encarnación Fernández Robledo, Enrique Alvarez-Llaneza García, Enrique José Pérez Parra, Enrique López De Briñas Y Banacloy, Enrique Sardaña Álvarez, Erika Tavera Gómez, Esperanza Martín Zapatero, Faustino Vega Pérez, Felipe Nicolau Pastríe, Félix Martín Santos, Fernando De Arriba Frade, Fernando Dolz Andrés, Fernando L Sancho Villanova, Fernando Marco Cardona, Fernando Martí-Vivaldi Martínez, Fernando Mayo Ferreiro, Fernando Sánchez-Toril López, Francisco De Pablo Cillero, Francisco Durán Hernández, Francisco Javier Balda Jau-regui, Francisco Javier Bartolomé Resano, Francisco Javier Fernández De Frutos, Francisco Javier Guerra Ramos, Francisco Javier Rodríguez Argüeso, Francisco Javier Tamayo Sicilia, Francisco Luis Gil Muñoz, Francisco Manuel Balaguer Montesinos, Francisco Martos Torres, Francisco Risco Sánchez, Francisco Samuel Fernández Escribano, Francisco Sangenis Biosca, Francisco Vaques Arias, Froilan Sáncez Sánchez, Gador Ramos Villalobos, Gemma Martínez Almagro, Gerardo Estruch Catalá, Germán Fernández López, German Saez Roca, Gonzalo Carles Hueso, Guadalupe Fernández Esteve, Guillermo Pérez Toledo, Gustavo Solince Gallardo, Hugo Dante García Ibarra, Ignacio Abascal Carey, Ignacio J Pérez De Diego, Inés Gil Gil, Irene De Lorenzo García, Isabel Lledó Fillol, Isidro Rodoreda Meillán, Jaime Creixell Sánchez, Javier Amiama Ruiz, Javier Antón Ortega, Javier Gallego Borrego, Javier Gallego Borrego, Jesús Armando Montero Abramonte, Jesús Castillo Ballesteros, Jesús Chamorro Romero, Jesús De La Fuente Pérez, Jesús Pastor Antón, Jesús Picazo Moreno, Jesús Zumeta Fustero, Joan Carle Caballero Dome-nech, Joan Clotet Solsona, Joan Cornet Sisquella, Joan Juvanteny Gorgals, Joan Ribot Pérez, Joan Ventosa Rodón, Joaquín Ferrandiz Miquel, Joaquín Salazar Vargas, Jorge Jorge Abad Capa, Pascual Bernabeu, José Antonio Carratalá Torregrosa, José Antonio Gómez Marco, José Antonio Martín Bernal, José Antonio Martín Soledad, José Berrocal Del Rio, José Burillo Arias, José Celdrán Gil, José Enrique Gavela García, José Enrique Lezcano Devesa, Jose Ignacio González Castellano, José Luis Colomer Martí, José Luis Del Rio Pedrosa, José Luis Fernández Menéndez, José Luis Rojas Box, José Maldonado Díaz De Losada, José Manuel Bretones Rodríguez, José Manuel Lorente Iniesta, José Manuel Muñoz Malagarriga, José María Esteve Ribelles, José María Jiménez Páez, José María Sánchez Mariscal, José Mario Salabert Rius, José Miguel Durán Durán, José Miguel Durán Durán, José Miguel Grima Barbero, José Pruñonosa Piera, José Sánchez Aldeguer, José Sanz Santos, José Vicente Campos Cristobal, Josep Comerma Barcelo, Josep María Alsina Martín, Josep María Benet Martí, Josep Maria Cuatrecasas Ardid, Josep María Jové Ysanta, Juan Abreu González, Juan Antonio Chavez Plasencia, Juan Antonio Lloret Queraltó, Juan Antonio Martínez Carbonell, Juan Antonio Royo Prats, Juan Antonio Sánchez Palau, Juan B Navarro González, Juan Barón Carrillo, Juan Carles Clara Riart, Juan Carlos Martín La Foz, Juan Enrique Luces Macias, Juan Francisco Andrade Bellido, Juan Francisco De Vega García, Juan Gil Carbonell, Juan Guallar Ballester, Juan Guijo Castro, Juan Hilanderas Jiménez, Juan Jiménez Guillén, Juan José Linares Linares, Juan José Martínez De La Torre, Juan Luis De La Torre Alvaro, Juan Luis García Rivero, Juan Manuel Acosta Méndez, Juan Manuel Meseguer Gil, Juan Manuel Nieto Somoza, Juan Manuel Verdeguer Miralles, Juan Miguel Sampol Company, Juan Ortiz De Saracho Y Boho, Juan Pablo García Muñoz, Juan Ramis Alemany, Juan Suárez Antelo, Juan Viles Valentí, Julia Vazquez Vazquez, Julián Ramón Garrido Jiménez, Julio Antonio García Cañizares, Julio Aurelio Gorriz Nuñez, Julio Portela Carreiro, Justo Grau Delgado, Khaled A Bdeir Egnyem, Larraitz Garcia Echeberria, Lirios Sacristán Bou, Lorenzo Jiménez Alfonso, Lucia Díaz Cañaveral, Lucia Díaz Cañaveral, Luis Antonio González Rodriguez, Luis Camara Cabrerizo, Luis Carlos Aguilar Martínez, Luis Emilio Del-gado Torices, Luis M Entrenas Costa, Luis Rodríguez Pas-cual, Luis Toca Enrique, Luisa Valladares Rodríguez, Maite Andreu Sabdell, Maite Gómara Urdiain, Manuel Carlos Barreiro Mourentan, Manuel Castilla Martínez, Manuel Cervera Del Pino, Manuel Mª Liñares Stolle, Manuel Mar-tínez Riaza, Manuel Miquel Palasi, Manuel Ocaña Torres, Manuel Pastor Rull, Manuel Salcedo Espinosa, Manuel Tor-res Pascual, Manuel Vicente Chincilla, Manuel Vila Justribó, Manuel Vila Justribó, Marc Bonnin Vilapalan, María Begoña Salinas Lasa, María Belén Alonso Ortiz, María Del Carmen Victoria López, Maria Del Pilar Ortega Castillo, María Dolores Gallardo García, María Dolores Mota Godoy, María Eugenia Casado López, María Isabel Parra Parra, María Jesús Avilés Inglés, María José Pericón Puyal, María Lucia Gascón Pedrola, Maria Luisa Moreno Tores, María Luisa Rivera Ortun, María Martínez Ceres, María Rosa Calderer Cardona, Mariano Muñoz Llanez, Marina C Rodríguez Hernández, Marta Palop Cervera, Miguel A Martín Pérez, Miguel Ángel Ciscar Vilanova, Miguel Angel García González, Miguel Angél López Aranda Miguel Angel Palomino Medina, Mireia Vila Santiago, Mishail Dahdouh Kuri, Mónica Cañero Torrecillas, Monserrat Llop Moreno, Monserrat Llordes Llordes, Narciso Fernández Carbajo, Natalia Carretero Suero, Nestor Almeida Pérez, Nur El-Homssi Jarsa, Nuria Castejón Pina, Pascual Llop Usó, Pascual Mañes Vicente, Patricia Lloberes Canadell, Patricia Mata Calderón, Pau Llacér Iborra, Pedro Penela Penela, Pedro Baños Hidalgo, Pedro J Romero Palacios, Pedro José De La Paz Gutierre, Pedro José López Villalba, Pedro Martínez Brugada, Pedro Pinto González, Pedro Vicioso Ranz, Pilar Lázaro Gracia, Pilar Marín Martínez, Rafael Belenguer Prieto, Rafael Calvet Madrigal, Rafael Castrodeza Sanz, Rafael Giménez Dome-nech, Rafael Lama Rodríguez, Rafael Machín Ramírez, Rafael Matoses Marco, Rafael Saez Valls, Rafael V Lluch Mota, Ramón Magarolas Jordá, Ramón Manuel Hernández Sadurní, Ramón Martínez Bretones, Ramón Tarrés Gimferrer, Raquel Llera Guerra, Roberto Veiga Gallego, Rodrigo Abad Rodríguez, Rosa María López Lisbona, Rosa Maria Pérez Nava, Rosario Cortina Rodríguez, Rosario Vargas González, Rossana Satorre Tomás, Rubén Andújar Espinosa, Rubén Saurent Helman, Salvador Bertran Folqué, Salvador Ruso Pacheco, Santiago Carrizo Sierra, Santiago Otaduy Bengoa, Sebastiana Pérez Rodríguez, Sergio Campos Téllez, Sergio Gallego Piote, Sergio Salvadó Vives, Silvia Molina Aguileras, Sonia Martínez Sáez, Teresa López Sangil, Teresa Peña Miguel, Tomás Lloret Pérez, Valentin Atxotegui Iraolagoitia, Valentina Moggi Zafferani, Vicente Gallego Rodríguez, Vicente Gomar Andrés, Vicente José Roig Figueroa, Vicente López Escrivá, Vicente Penades Vaya, Vicente Poveda Gran, Victor Jiménez Castro, Victor Vera Campillo, Virginia Serrano Gutierrez, Xavier Alfaro Rodriguez, Xavier Arnal Marcé, Xavier Casals Reynals, Xavier Martínez Álvarez, Xavier Ureta I Boixadera, Xavier Vilá Giralte, Xavier Vila Reyner, and Yolanda Galea Colón.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Marc Miravitlles has received speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Teva, Grifols, and Novartis and consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Gebro Pharma, CLS Behring, Cipla, MediImmune, Mereo Biopharma, Teva, Novartis, and Grifols. Carlos Roncero has received fees to give talks for Janssen-Cilag, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ferrer-Brainfarma, Pfizer, Reckitt Benckiser, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Lilly, GSK, Rovi, and Adamed. He has received financial compensation for his participation as a member of the Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, and Shire boards and conducted the PROTEUS project, which was funded by a grant from Reckitt-Benckisert. Anna Campuzano and Joselín Pérez are full-time employees of Grupo Ferrer (Barcelona, Spain). José Antonio Quintano has received speaker fees from Almirall, Bayer, Boehringuer, Ferrer, GSK, Novartis, Menarini, and TEVA; consulting fees from Almirall, Boehringuer, Ferrer, Menarini, Novartis, Mundipharma; and registration support for medical congresses from Almirall, Pfizer, Gebro, GSK, Mundipharma, Novartis, and ROVI. Jesús Molina has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Mundifarma, and Pfizer and consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Gebro Pharma, Mundifarma, and GlaxoSmithKline. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Author contributions

MM wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed toward the study design, planning and interpretation of data analysis, and critically revising the paper; they approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Jones PW, Brusselle G, Dal Negro RW, et al. Properties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European study. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(1):29–35. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00177210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648–654. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Pinto LM, Morogan A, Bourbeau J. The COPD assessment test: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(4):873–884. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00025214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miravitlles M, García-Sidro P, Fernández-Nistal A, et al. The chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test (CAT) improves the predictive value of previous exacerbations for poor outcomes in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulm on Dis. 2015;10:2571–2579. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S91163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.García-Sidro P, Naval E, Martínez Rivera C, et al. The CAT (COPD Assessment Test) questionnaire as a predictor of the evolution of severe COPD exacerbations. Respir Med. 2015;109(12):1546–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Rivero JL, Esquinas C, Barrecheguren M, et al. Risk factors of poor outcome after admission for a COPD exacerbation. Multivariate logistic predictive models. COPD. 2017;14(2):164–169. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1260538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casanova C, Marin JM, Martinez-Gonzalez C, et al. Differential Effect of Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea, COPD assessment test, and clinical COPD questionnaire for symptoms evaluation within the new GOLD staging and mortality in COPD. Chest. 2015;148(1):159–168. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martínez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(1):128–149. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karloh M, Fleig Mayer A, Maurici R, Pizzichini MM, Jones PW, Pizzichini E. The COPD assessment test: what do we know so far?: a systematic review and meta-analysis about clinical outcomes prediction and classification of patients into GOLD stages. Chest. 2016;149(2):413–425. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyazaki M, Nakamura H, Chubachi S, et al. Keio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR) Group Analysis of comorbid factors that increase the COPD assessment test scores. Respir Res. 2014;15:13. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miravitlles M, Molina J, Quintano JA, et al. DEPREPOC Study Investigators Factors associated with depression and severe depression in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2014;108(11):1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bestall J, Paul E, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones P, Wedzicha J. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581–586. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MÁ, Sánchez LS, Tordera MP, Sánchez PR. Severe exacerbations and BODE index: two independent risk factors for death in male COPD patients. Respir Med. 2009;103(5):692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramon MA, Esquinas C, Barrecheguren M, et al. Self-reported daily walking time in COPD: relationship with relevant clinical and functional characteristics. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1173–1181. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S128234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, Kraus A, Sauer H. On the validity of the beck depression inventory. A review. Psychopathology. 1998;31(3):160–168. doi: 10.1159/000066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobo A, Saz P, Marcos G, et al. Revalidation and standardization of the cognition mini-exam (first Spanish version of the Mini-Mental Status Examination) in the general geriatric population. Med Clin (Barc) 1999;112(20):767–774. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villeneuve S, Pepin V, Rahayel S, et al. Mild cognitive impairment in moderate to severe COPD: a preliminary study. Chest. 2012;142(6):1516–1523. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morishita-Katsu M, Nishimura K, Taniguchi H, et al. The COPD assessment test and St George’s respiratory questionnaire: are they equivalent in subjects with COPD? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1543–1551. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S104947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YS, Park S, Oh YM, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test can predict depression: a prospective multi-center study. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(7):1048–1054. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.7.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodd JW, Hogg L, Nolan J, et al. The COPD assessment test (CAT): response to pulmonary rehabilitation. A multicentre, prospective study. Thorax. 2011;66(5):425–429. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.156372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dal Negro RW, Bonadiman L, Turco P. Sensitivity of the COPD assessment test (CAT questionnaire) investigated in a population of 681 consecutive patients referring to a lung clinic: the first Italian specific study. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2014;9(1):15. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva Júnior JL, Conde MB, de Sousa Corrêa K, da Silva C, da Silva Prestes L, Rabahi MF. COPD assessment test (CAT) score as a predictor of major depression among subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and mild hypoxemia: a case-control study. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papaioannou M, Pitsiou G, Manika K, et al. COPD assessment test: a simple tool to evaluate disease severity and response to treatment. COPD. 2014;11(5):489–495. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2014.898034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Torres I, Valenza MC, Torres-Sánchez I, Cabrera-Martos I, Rodriguez-Torres J, Moreno-Ramírez MP. Changes in cognitive status in COPD patients across clinical stages. COPD. 2016;13:327–332. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1081883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dulohery MM, Schroeder DR, Benzo RP. Cognitive function and living situation in COPD: is there a relationship with self-management and quality of life? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1883–1889. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S88035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schure MB, Borson S, Nguyen HQ, et al. Associations of cognition with physical functioning and health-related quality of life among COPD patients. Respir Med. 2016;114:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleutjens FAHM, Spruit MA, Ponds RWHM, et al. Cognitive impairment and clinical characteristics in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2017 Jan 1; doi: 10.1177/1479972317709651. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roncero C, Campuzano A, Quintano JA, Molina J, Pérez J, Miravitlles M. Cognitive status among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulm on Dis. 2016;11:543–551. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S100850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calle M, Casamor R, Miravitlles M. Identification and distribution of COPD phenotypes in clinical practice according to Spanish COPD Guidelines: the FENEPOC study. Int J Chron Obst Pulm Dis. 2017;12:2373–2383. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S137872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calle Rubio M, Alcazar Navarrete B, Soriano JB, et al. Clinical audit of COPD in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain: the EPOCONSUL study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:417–426. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S124482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]