Abstract

Purpose

To define the genetic spectrum and relative gene frequencies underlying clinical frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

Methods

We investigated the frequencies and mutations in neurodegenerative disease genes in 121 consecutive FTD subjects using an unbiased, combined sequencing approach, complemented by cerebrospinal fluid Aβ1-42 and serum progranulin measurements. Subjects were screened for C9orf72 repeat expansions, GRN and MAPT mutations, and, if negative, mutations in other neurodegenerative disease genes, by whole-exome sequencing (WES) (n = 108), including WES-based copy-number variant (CNV) analysis.

Results

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic mutations were identified in 19% of the subjects, including mutations in C9orf72 (n = 8), GRN (n = 7, one 11-exon macro-deletion) and, more rarely, CHCHD10, TARDBP, SQSTM1 and UBQLN2 (each n = 1), but not in MAPT or TBK1. WES also unraveled pathogenic mutations in genes not commonly linked to FTD, including mutations in Alzheimer (PSEN1, PSEN2), lysosomal (CTSF, 7-exon macro-deletion) and cholesterol homeostasis pathways (CYP27A1).

Conclusion

Our unbiased approach reveals a wide genetic spectrum underlying clinical FTD, including 11% of seemingly sporadic FTD. It unravels several mutations and CNVs in genes and pathways hitherto not linked to FTD. This suggests that clinical FTD might be the converging downstream result of a delicate susceptibility of frontotemporal brain networks to insults in various pathways.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, frontotemporal dementia, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, whole-exome sequencing

Introduction

The term “frontotemporal dementia” (FTD) describes a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders sharing progressive degeneration of frontotemporal networks as a common hallmark. Clinically, FTD comprises behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), the semantic variant (svPPA), and the nonfluent variant (nfPPA) of primary progressive aphasia.1, 2, 3 However, behavioral and aphasic presentations of frontotemporal network degeneration can also be caused by underlying amyloid pathology, e.g., in behavioral variant AD (bvAD)4 and logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA).3 This is in line with several postmortem studies demonstrating that clinically and neuropathologically diagnosed FTD can result from different underlying pathologies (e.g., tau, TDP-43, or amyloid pathology), indicating that multiple pathogenic pathways might result in converging and/or overlapping clinical phenotypes.5

Corresponding with this complex pathological architecture of FTD, genes in manifold pathways have recently been implicated in its molecular pathogenesis.6 However, the full spectrum of neurodegenerative disease (NDD) genes and the relative proportions in which each contributes to the complex genetic architecture of FTD have not yet been systematically explored in a strictly consecutive series and using unbiased sequencing approaches. Here, we provide a systematic analysis of the frequencies and mutations in genes known to contribute to FTD/ALS and other NDDs in a consecutive series of 121 subjects with clinical FTD syndromes, combining successive Sanger sequencing, C9orf72 repeat primed polymerase chain reaction (PCR), whole-exome sequencing (WES) and WES-based copy-number variation (CNV) analysis. We hypothesized that mutations are found in a substantial proportion of clinical FTD subjects, even in the absence of a positive family history, and also in genes hitherto not linked to FTD phenotypes.

Materials and methods

Subjects, clinical phenotyping, and biomarker analysis

A strictly consecutive series of 121 unrelated FTD subjects of Caucasian ancestry (over 90% from Southern Germany) was recruited at the Department for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Center for Neurology, Tübingen, Germany, from 2009 to 2014. All subjects were clinically diagnosed with FTD according to international consensus criteria.1, 2 Family history was positive for NDD in 33.9% (n = 41), as defined by the presence of one or more first- or second-degree relatives affected by any type of NDD. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Tübingen, and written consent was obtained from all participants and their legal representatives.

All subjects received a systematic neurological assessment and, when possible, routine brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (for further methods on clinical phenotyping, see Supplementary Material S1 online, for summary of the clinical features on the group level, see Table 1; for details of each subject, see Supplementary Material S2). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid-beta-42 (Aβ1-42), and serum progranulin levels were determined using commercially available ELISA sets for all individuals when CSF and serum, respectively, were available (CSF Aβ1-42 available for 97/121; serum progranulin available for 45/121) (for further methods, see Supplementary Material S1). This allowed investigation of the biomarker changes associated with both mutation-positive and mutation-negative clinical FTD.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the FTD cohort.

| Total number of subjects | 121 |

|---|---|

| Clinical syndrome | |

| bvFTD | 58 (47.9%) |

| nfPPA | 48 (39.7%) |

| svPPA | 7 (5.8%) |

| lvPPA | 8 (6.6%) |

| Additional features | |

| ALS | 16 (13.2%) |

| Parkinsonism | 12 (9.9%) |

| Family history of neurodegenerative disease | |

| Familial | 41 (33.9%) |

| Sporadic | 73 (60.3%) |

| Unknown | 7 (5.8%) |

| Average age of onset | |

| All subjects | 62.7 (range 30–84) years |

| Familial subjects | 59.2 (range 30–81) years |

| Sporadic subjects | 64.1 (range 32–83) years |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; bvFTD, behavioral variant; lvPPA, logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia; nfPPA, nonfluent primary progressive aphasia; svPPA, semantic variant primary progressive dementia.

Genetic screening strategy and methods

A two-step genetic screening strategy was geared toward identifying a causal variant in as many subjects as possible, starting with the presumably common genetic causes in step 1, and continuing to rarer genetic causes in step 2 (Supplementary Material S3). In step 1, all subjects were tested for the presumably most common genetic causes of FTD in central Europe at the time of sequencing (2014), namely for repeat expansions in C9orf72 (repeat lengths ≥30 considered pathogenic) as well as for variants in GRN and MAPT. The two latter genes were sequenced either selectively by Sanger sequencing or as part of a high-coverage high-throughput Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) SureSelect panel including 23 FTD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and selected other early-onset dementia genes (for a complete list of the genes see Supplementary Material S4; for details on the genetic panel method, see Supplementary Material S1).

In step 2, all 108 subjects that were tested negative for repeat expansions in C9orf72 and for pathogenic mutations in GRN and MAPT (or any other gene covered by the panel) were investigated by WES (Supplementary Material S4). Genes of interest were selected based on previous NDD gene searching7 and additional systematic literature review in search of genes implicated in FTD/ALS and other types of dementia. In total, 94 genes previously associated with FTD/ALS and other dementias (the set created based on existing literature in December 2015) were selected for analysis (for a full list of genes, see Supplementary Material S4). Quality control, gene-based and impact-score annotations, and population database frequencies were assigned to the variants, using ANNOVAR. Variants were filtered for (i) nonsynonymous coding variants (missense and loss of function (LOF) variants) and variants overlapping with putative splice sites (up to 25 bp of exon–intron junctions), that were (ii) absent or extremely rare (minor allele frequency <0.0005) in the public databases ExAC (version 0.3.1) and ESP6500 (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), and (iii) predicted pathogenic by at least one of the following in silico software algorithms: SIFT (J. Craig Venter Institute, La Jolla, CA), Polyphen-2, LRT, CADD (University of Washington and HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL) (Phred score ≥20) and DANN (Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine, CA) (score ≥0.98). The pathogenicity of the resulting variants was determined via a conservative multistep case-by-case analysis using the following criteria: (i) bioinformatic results on disease allele frequency and in silico predictions (same tools as for filtering), (ii) existing literature on these variants, (iii) manual curation on mutation type, domain location, and frequency in public databases, (iv) segregation analysis (where available), and (v) functional biomarkers known to be altered for pathogenic variants in the respective genes (e.g., progranulin for GRN, Aβ1-42 for PSEN, cholesterol metabolites for CYP27A1, arylsulfatase A activity for ARSA variants).

WES-based CNV analysis was applied using eXome-Hidden Markov Model (XHMM) software8 (for further details, see Supplementary Material S1). Positively curated CNVs were validated using quantitative PCR (qPCR) or multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. In total 112 subjects were investigated by at least one next-generation sequencing technique (panel: n = 33; WES: n = 108; n = 29 by both), thus also allowing simultaneous identification of possible multiple variants in several genes of interest in the majority of the included subjects.

Results

Overview of the identified genetic variants

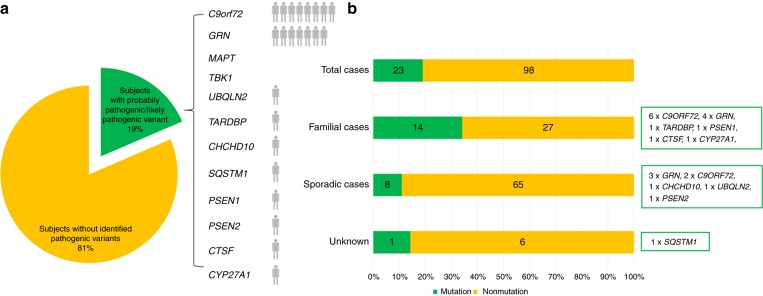

Our combined sequencing approach yielded a total of 87 variants in the 94 analyzed FTD/ALS and other dementia genes, identified in 66 different individuals (for an overview of these 87 variants, see Supplementary Material S5). Twenty-four of the 87 variants, identified in 23 different individuals and affecting 10 distinct genes, were considered pathogenic or likely pathogenic (14 single nucleotide variants, eight C9orf72 repeat expansions and two CNVs, one subject carrying two compound heterozygous variants) (Table 2 and Figure 1a), with nine variants being novel, i.e., not previously associated with human disease (for an overview, see Supplementary Material S5). This gives a total frequency of 23/121 (19%) mutation carriers with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. Family history in pathogenic/likely pathogenic mutation carriers was positive for NDD in 61% (14/23) subjects, while it was sporadic or unknown in 39% (9/23) of subjects. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations (for the criteria, see “Materials and Methods”) were found in 11% (8/73) of sporadic subjects, encompassing largely the same gene spectrum as observed in the familial subjects (Figure 1b). Age of onset was significantly lower in the mutation carrier group than in the non-mutation carrier group (56.4 (SD = 11.5) vs. 64.2 (SD = 9.8) years, Mann-Whitney U test, two-tailed P < 0.0078).

Table 2. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants identified in 121 clinical frontotemporal dementia subjects.

| Gene, no. of mutation carriers (percentage) (n = 121) | Subject | Phenotype | Variant | Amino acid change | Mutation class | MAF in ExAC | SIFT | Polyphen-2 | LRT | CADD | DANN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C9orf72, 8 (6.6%) | 16265 | nfPPA | Repeat expansion | n.a. | Repeat expansion | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 18890 | nfPPA | ||||||||||

| 19115 | nfPPA | ||||||||||

| 19750 | bvFTD | ||||||||||

| 20879 | bvFTD | ||||||||||

| 21899 | bvFTD | ||||||||||

| 22181 | nfPPA | ||||||||||

| 29999 | bvFTD | ||||||||||

| GRN, 7 (5.8%) | 13413 | bvFTD | Exon7:c.T687G | Y229X | Stopgain | 0 | . | . | . | 35 | 0.995 |

| 18167 | bvFTD | Exon 2–12 deletion | n.a. | Deletion (see Figure 2a) | . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 19869 | nfPPA | Exon10:c.985_986insAC | p.D329fs | Frameshift insertion | 0 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 21804 | bvFTD | Exon7:c.708+1G>A | n.a. | Splicing | 8.28E−6 | . | . | . | 26.3 | 0.996 | |

| 21895 | bvFTD | Exon10:c.C1117T | p.P373S | Missense | 0 | D | P | D | 24.5 | 0.998 | |

| 23603 | nfPPA | Exon4:c.C328T | p.R110X | Stopgain | 0 | . | . | . | 29.4 | 0.994 | |

| 23812 | svPPA | Exon8:c.759_760del | p.C253fs | Frameshift deletion | 0 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| UBQLN2, 1 (0.8%) | 18527 | bvFTD | Exon1:c.C845T | p.A282V | Missense | 0 | D | D | D | 24.7 | 0.999 |

| CHCHD10, 1 (0.8%) | 21854 | bvFTD | Exon2:c.C176T | p.S59L | Missense | 0 | D | P | D | 34 | 0.999 |

| SQSTM1, 1 (0.8%) | 22531 | bvFTD | Exon8:c.C1174G | p.P392A | Missense | 0 | D | D | D | 26.8 | 0.995 |

| TARDBP, 1 (0.8%) | 22458 | bvFTD | Exon6:c.G1144A | p.A382T | Missense | 0 | T | B | N | 13.06 | 0.98 |

| PSEN1, 1 (0.8%) | 18439 | bvFTD | Exon9:c.869-2A>G | N/A | Splicing | 0 | . | . | . | 24.9 | 0.995 |

| PSEN2, 1 (0.8%) | 18506 | lvPPA | Exon8:c.T713C | p.L238P | Missense | 0 | D | D | D | 26.8 | 0.999 |

| CYP27A1, 1 (0.8%) | 23660 | bvFTD | Exon6:c.C1183A | p.R395S | Missense (homozygous) | 8.25E−6 | D | D | D | 34 | 0.998 |

| CTSF, 1 (0.8%) | 19566 | bvFTD | Exon13:c.T1394G | p.L465W | Missense + | 0 | D | D | D | 27.1 | 0.966 |

| 19566 | bvFTD | Exons 1–6 deletion | Deletion (see Figure 2b) | . | . | . | . | . | . |

B, benign; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; CADD, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; D, deleterious or probably damaging; DANN, deleterious annotation of genetic variants using neural networks; ExAC, Exome Aggregation Consortium database; LRT, likelihood ratio test; lvPPA, logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia; MAF, minor allele frequency; N, neutral; n.a, not applicable; nfPPA, nonfluent primary progressive aphasia; P, possibly damaging; SIFT, predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm; svPPA, semantic variant primary progressive aphasia; T, tolerant;

Figure 1.

Relative frequencies of mutations in neurodegenerative disease (NDD) genes in a consecutive series of 121 subjects with clinical frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Twenty-three subjects carried mutations, which were distributed across common FTD genes (C9orf72 repeat expansion, GRN, but surprisingly not MAPT or TBK1), less common FTD genes (CHCHD10, SQSTM1, TARDBP, UBQLN2), and also NDD genes not commonly linked to FTD (PSEN1, PSEN2, CTSF, CYP27A1) (a). Mutations were found not only in 34% of familial subjects, but also in 11% of sporadic subjects (b).

Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in established FTD genes

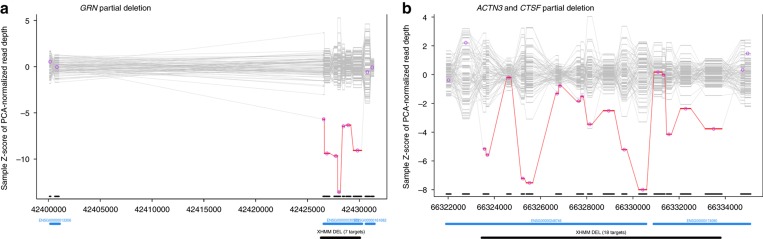

The most frequent finding was C9orf72 repeat expansions, observed in eight subjects (8/121 (6.6%)), followed by pathogenic GRN variants in seven subjects (7/121 (5.7%)). Six of these seven GRN subjects carried truncating GRN variants (two frameshifts (c.759_760del:p.C253fs and c.985_986insAC:p.D329fs), two stop mutations (c.C328T:p.R110X and c.T687G:p.Y229X), one splicing variant (c.708+1G>A), and even one macro-deletion, spanning exon 2–13 (3.5 kb) (Figure 2a, confirmed by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification)). For three of the six subjects with truncating variants (one frameshift, one stop, and the large deletion), CSF and serum progranulin levels were available, all showing severely reduced progranulin levels (median CSF progranulin level: 1.8 ng/ml, median serum progranulin level: 10.4 ng/ml), for individual levels, see Supplementary Material S2), corroborating their pathogenicity. In addition to these six pathogenic LOF GRN variants, we identified one missense variant in GRN (c.C1117T:p.P373S, in subject 21862). For the following reasons, this variant might be pathogenic: it segregates with disease, is absent in ExAC, is predicted to be damaging by all five algorithms, affects an amino acid highly conserved through evolution, and is associated with reduced CSF progranulin levels, decreased to the same range as in LOF mutation carriers (CSF progranulin level in subject 21862: 2.4 ng/ml), thus indicating progranulin haploinsufficiency in the central nervous system compartment (for a detailed discussion of these findings, see Wilke et al.9). In contrast to previous reports on genetic FTD, we did not identify any pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in MAPT or TBK1, despite good average coverage with >35x of the exonic regions.

Figure 2.

Copy-number variants in GRNand CTSF detected by whole-exome sequencing. Two deletions were identified, affecting exons 2–12 of GRN in subject 18167 (a) and exons 1–6 of CTSF (plus exons 8–21 of ACTN3) in subject 19566 (b), respectively. The start and end points of both deletions were located in regions captured by the exome and the exact start and end points could be determined by visualizing the sequence data in the integrative genomics viewer (GRN deletion chr17:42,426,438–42,430,018; CTSF deletion chr11:66,323,324–66,333,606 (hg19)).

In addition to variants in these presumed common FTD genes, we also identified four likely pathogenic variants in four less common FTD genes: UBQLN2 (c.C845T:p.A282V), TARDBP (c.G1144A:p.A382T), SQSTM1 (c.C1174G:p.P392A), and CHCHD10 (c.C176T:p.S59L). As the UBQLN2 and TARDBP variants have been described in detail elsewhere10, 11 (for functional proof of pathogenicity of the TARDPB A382T see Mutihac et al.12 Orru et al.13) we focus here on the SQSTM1 and CHCHD10 variants. Both variants are likely pathogenic for the following reasons: they are absent in ExAC, predicted to be damaging by all five algorithms, change an amino acid highly conserved through evolution, and affect the very same amino acid as do other already established pathogenic SQSTM1 and CHCHD10 mutations.

The SQSTM1 variant affects the same amino acid as does another well-established, frequent SQSTM1 mutation, namely the p.P392L mutation.14 The p.P392L mutation has almost exclusively been associated with FTD phenotypes complicated by either ALS14 or Paget disease of bone,15 or with ALS phenotypes, presenting the most common SQSTM1 variant in ALS subjects from the United Kingdom.16 In contrast, the subject identified here (22531) presented with a pure bvFTD phenotype without signs of either ALS or parkinsonism, demonstrating that also pure FTD phenotypes can be part of the ALS-FTD phenotype spectrum caused by p.P392 SQSTM1 amino acid changes. This subject showed no clinical signs of bone disease.

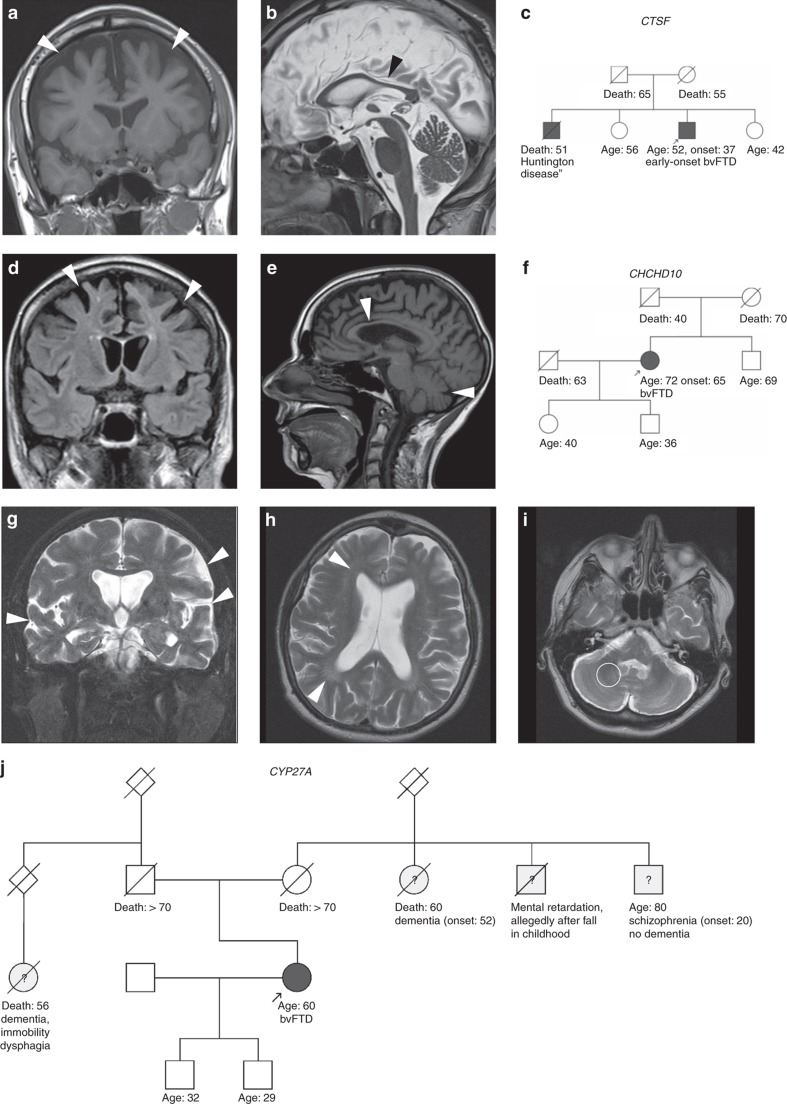

The p.S59L CHCHD10 variant has been associated with a variety of syndromes, including motor neuron disease and/or (unspecified) dementia plus, in some subjects, cerebellar ataxia.17 Here we identified this variant in a bvFTD subject (21854) without signs of ALS or other NDD, thus reporting the first pure FTD phenotype of the p.S59L CHCHD10 variant, and demonstrating that insults in mitochondrial proteins can lead to pure FTD (for MRI and pedigree, see Figure 3d–f; for a more detailed subject description, see Supplementary Material S6).

Figure 3.

Examples of rare genetic causes of clinical frontotemporal dementia (FTD): brain imaging and pedigrees of CTSF,CHCHD10 and CYP27A1 mutation carriers. (a–c) CTSF subject. MRI of the CTSF subject (19566) showed frontotemporal atrophy (a) and thinning of the corpus callosum (b), but no definite white matter hyperintensity, demonstrating that CTSF mutations can present even with only unspecific FTD brain imaging changes. Family history revealed adult-onset behavioral change and cognitive decline in the deceased brother who was diagnosed with “Huntington disease” (c). (d–f) CHCHD10 subject. MRI of the CHCHD10 subject (21854) revealed bilateral frontal atrophy (d), mild cerebellar atrophy (e), and thinning of the corpus callosum (e). This subject appeared to be sporadic, but family history was incomplete owing to early death of the father (f). (g–j) CYP27A1 subject. The MRI of the CYP27A1 subject (23660) also showed predominantly temporal and frontal atrophy (g), and only unspecific, mild periventricular white matter changes (h), but no characteristic signal alterations of the dentate nucleus (i). This demonstrates that CYP27A mutations can also present with only unspecific FTD brain imaging changes, and can thus easily be overlooked in clinical practice. Clinical workup was at first misdirected by the presumed autosomal–dominant pattern of inheritance of a neuropsychiatric disease (j), before next-generation sequencing unraveled clearly pathogenic autosomal–recessive CYP27A1 mutations in the index subject, indicating that there must be other causes for the neuropsychiatric diseases in the other family members (for a more detailed discussion of the subject’s family history, see Supplementary Material S7).

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in genes not commonly associated with clinical FTD

While variants in PSEN1 and PSEN2 have been linked to clinical FTD phenotypes before, reports on this association are still rare.18 In the present study we identified one pathogenic PSEN1 splicing variant (c.869-2A>G; subject 19495) and one likely pathogenic PSEN2 missense variant (c.T713C:p.L238P; subject 18506). In addition to the in silico data (see Supplementary Material S5), the pathogenicity of both PSEN variants was further corroborated by the finding of reduced CSF Aβ1-42 in both subjects (19495: 199 pg/ml; 18506: 440 pg/ml; for an earlier, detailed discussion of these findings, see Blauwendraat et al.19).

Surprisingly, we also observed one homozygous variant in CYP27A1 (c.C1183A:p.R395S). This established mutation has been demonstrated to lead to alternative pre-mRNA splicing and decreased sterol 27-hydroxylase activity, thereby causing cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis.20 To confirm the pathogenicity of this variant, we confirmed the characteristic reduction of 27-OH-cholesterol (below the detection threshold), a sterol 27-hydroxylase product, and compensatory increases of 7-alpha-OH-cholesterol (1372 ng/ml) and cholestanol (3410 ng/dl) in our patient. This subject presented with impulsivity, disinhibition, apathy, and executive deficits at the age of 49 years, associated with pyramidal signs (for pedigree see Figure 3j; for more subject and pedigree details, see Supplementary Material S7). Remarkably, routine MRI revealed unspecific frontotemporal atrophy, but no specific cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis imaging changes (Figure 3g–i), demonstrating that this treatable condition can easily be overlooked in unexplained FTD subjects, even if caused by clearly pathogenic CYP27A1 mutations.

In one subject (19566) we also found compound heterozygous mutations in the recently identified lysosomal lipofuscinosis gene CTSF.21 These include a missense variant (c.T1394G:p.L465W) located in trans with the first ever reported macro-deletion in this gene (10kb deletion spanning exons 6–13) (Figure 2b, deletion confirmed by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification). The missense variant is likely pathogenic as it is absent in ExAC, is predicted to be damaging by four of the five algorithms, and affects an amino acid highly conserved through evolution. This is the first report of a clinical FTD phenotype caused by CTSF mutations. The subject presented at the age of 37 years with an early-onset bvFTD phenotype comprising executive deficits, apathy, reduced empathy, and mild disinhibition, as well as clinical evidence of pyramidal involvement and mild apraxia. In contrast to previously described CTSF mutation carriers, the disease in this subject was not complicated by epileptic seizures, neither prior to dementia onset nor during the further course of the disease. Routine MRI revealed unspecific frontotemporal atrophy, but no specific imaging changes, demonstrating also that this condition can easily be overlooked in clinical practice (for MRI and pedigree, see Figure 3a–c; for a detailed subject description, see Supplementary Material S8). For more details of the identified variants, see Table 2 and Supplementary Material S5.

Variants of uncertain significance, and deconstructing pathogenicity of the T410I ARSA variant

In addition, the WES filter settings (see “Materials and Methods”) yielded 63 variants of uncertain significance (VUS), which might be pathogenic, but for which strict evidence is currently lacking to classify them as potentially causative, according to our conservative variant interpretation approach. The observed VUS include changes in the genes APP, ATXN2, CCNF, PRPH (duplication), and TBK1 (for a more detailed genetic and clinical discussion of the variants in these genes, see Supplementary Material S9).

The need for such a conservative, cautious approach when interpreting VUS in NDD genes is exemplified by the observed missense ARSA variant (c.C1229T:p.T410I). This variant, identified here in a homozygous state, is currently assumed to be pathogenic, reportedly causing “metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) presenting with a late-onset neuropathy,”22 and listed as pathogenic in ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/3092/). However, the subject identified here (20103) (i) presented with a clear bvFTD phenotype with age at onset of 65 years, which would be untypical for ARSA-associated disease/MLD; (ii) repeated detailed MRI at 67 and 71 years did not reveal any evidence for even subtle MLD changes; and, most importantly; (iii) repeated testing of arylsulfatase A activity was normal (1.43 IU/106 cells, norm: >0.4 IU/106 cells) (for a more detailed description, see Supplementary Material S10). These three findings provide evidence that the claim of pathogenicity for the p.T410I ARSA variant needs to be revised.

Cerebrospinal fluid and serum biomarker findings

We observed a CSF Aβ42 reduction <550 pg/ml23 not only in the two PSEN subjects, but also in two individuals with clearly pathogenic GRN mutations (13413 and 18167) (Supplementary Material S11). Similarly, a serum progranulin reduction below the established <110 ng/ml threshold for GRN LOF mutations24, 25 was found not only in all the GRN LOF carriers for whom progranulin measurements were available but also in the CHCHD10 missense carrier (Supplementary Material S11). These findings indicate that alterations in Aβ42 and progranulin levels are not restricted to AD and FTD-GRN subjects, respectively, but are a recurrent finding in other FTD subjects, representing possible downstream effects of mutations in other FTD genes (here: GRN/CHCHD10) and/or concomitant age-related amyloid/progranulin pathology.

Discussion

The genetic spectrum of clinical FTD: frequencies in a strictly consecutive series

Our study presents a systematic genetic in-depth study of a strictly consecutive series of clinical FTD subjects. Such a consecutive series, in which all subjects are either finally genetically solved or at least characterized as C9orf72 repeat- and WES-negative, including WES-based CNV analysis, is crucial for unraveling the frequencies and distributions of genetic defects in clinical FTD. Other current frequency studies usually exclude subjects in whom a genetic defect has been found before (e.g., C9orf72 expansions, GRN, or MAPT), describe nonconsecutive series based on prior explicit or implicit selection criteria, or study only single genes or a small set of genes, without screening all genes associated with neurodegenerative dementias, and thus do not provide an unbiased, representative estimate of the full genetic landscape of clinical FTD.15, 26, 27

In total, we identified 24 different pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations in 23 subjects (23/121 (19%)), including eight seemingly sporadic subjects, and damaging ten different genes. This demonstrates that an unbiased genetic sequencing approach might allow the explanation of a substantial proportion of clinical FTD subjects, even in the absence of a positive family history. These numbers probably represent an underestimate, given that we identified 63 additional potentially pathogenic variants in FTD/ALS and other dementia genes and pathways, for which we took a conservative approach by classifying them as VUS. The negative family history in the mutation carriers with sporadic FTD (8/73 (11%) of all sporadic patients) might be explained by death of the parental generations before onset of disease; by underappreciated NDD in previous generations; and in particular by the incomplete penetrance which has been reported for almost all FTD genes. The fact that 9/23 (39%) of the subjects who had a positive family history for NDD did not show an obvious causal mutation demonstrates a still substantial amount of “missing heritability” in FTD genetics. This indicates the need for more advanced genetic techniques (e.g., whole-genome sequencing combined with RNA sequencing) allowing the capture of genetic variation in regulatory regions, RNA genes, and noncoding intronic regions.

Frequencies of “standard” FTD genes

While the frequency of C9orf72 repeat expansions (6.6%) and of GRN variants (5.8%) is in concordance with the reported European frequencies,28, 29 indicating that our subject cohort was broadly comparable to other FTD screening cohorts, we did not detect any probable pathogenic variants in MAPT and TBK1. Pan-European frequencies are reported at about 8% for MAPT29 and 0.4% for TBK1,30 with frequencies up to 17.8% for MAPT31 and 1.7% for TBK132 in Dutch and Belgian populations, respectively. These findings add further evidence for substantial differences in mutation frequencies of common FTD genes, depending on the European population, with only very rare occurrences of MAPT mutations having been reported e.g., also in a Finnish cohort.33 These population differences have to be interpreted with caution, as they might also be partly influenced by between-center and between-country differences in subject recruitment. Nevertheless, they have to be accounted for when providing frequency numbers in the general public and for epidemiological studies, and when planning future observation and treatment studies in FTD.

While 15 of 121 (12.4%) subjects were thus explained by mutations in one of these assumed as common FTD genes that are frequently sequenced in clinical routine (C9orf72, GRN, MAPT, and TBK1), 8 (6.6%) of the FTD subjects could be explained by mutations in other genes. This has important implications for clinical practice and genetic diagnostics. It shows that manifold genetic causes of FTD are missed if only the FTD genes assumed as frequent are tested in the routine workup. Our approach thus exemplifies the power of unbiased next-generation sequencing, capturing all standard, non-standard FTD genes, including CNV analyses, and the need to introduce it into clinical practice. This will allow appreciating the extensive genetic background of clinical FTD syndromes.

The wide genetic spectrum of clinical FTD: novel “nonstandard” FTD genes

Our unbiased genetic approach also allowed us to substantially extend the genetic spectrum underlying clinical FTD, unraveling several genes that have traditionally not been considered as FTD genes. For example, as shown here and elsewhere,18 mutations in PSEN1 and PSEN2 can present with a behavioral FTD syndrome, in which the clinical syndromes of bvFTD and behavioral variant AD4 become almost clinically indistinguishable (for more extensive discussions of these two mutation carriers see Blauwendraat et al.19). However, we now show that nonstandard dementia genes and models of autosomal-recessive inheritance also need to be considered in the workup and pathogenesis of clinical FTD syndromes. Our finding of a homozygous CYP27A1 subject adds to the increasing list of unusual adult-onset cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis phenotypes34 and more specifically, adds support for FTD as a recurrent phenotype, as hypothesized by several single-case reports.35, 36

CTSF mutations have recently been identified as causing type B Kufs disease, an adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, associated with a severe, early-onset neuropsychiatric phenotype with early epileptic seizures,21, 37 and more recently one family with early-onset AD phenotype has been reported.38 We now show that an adult-onset FTD phenotype, without seizures, can also be caused by CTSF mutations, thus extending the genetic and molecular basis of clinical FTD. This finding adds to the increasingly appreciated notion of insults in lysosomal pathways as an important contributor to the molecular architecture of FTD.39 Homozygous GRN mutations have already been shown to cause adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis39 and a pathobiochemical overlap of FTD and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis has been shown for Grn(−/−) mice (as a model for progranulin pathology) and, vice versa, also for Ctsd(−/−) mice (as a model for ceroid lipofuscinosis pathology) with progranulin being involved in the regulation of different cathepsin proteins.39 Our findings also extend the mutational spectrum of CTSF disease, by unraveling the first macro-deletion in CTSF. This shows the need to complement future genetic routine diagnostics of CTSF with CNV analyses that would not be captured by routine Sanger sequencing or standard WES analysis. In both subjects (CYP27A1, CTSF) MRI showed only unspecific frontotemporal atrophy, but no disease-specific changes (Figure 3), indicating that these conditions might easily be overlooked in subjects with unexplained FTD.

At the same time, our findings also revise some of the reported extended genotype–phenotype relations. The p.T410I variant in the MLD gene ARSA has been reported and to cause a mild, very late-onset neuropathy phenotype.22 We here report the first subject with this variant in a homozygous state, showing neither neuropathy nor MLD, and in particular exhibiting normal ARSA activity, thus casting doubt on the pathogenicity of this variant and thus of the reported ARSA phenotype. This finding illustrates the importance of constant critical clinical reanalysis of the manifold genetic variants produced by WES, which needs to include (as shown here) also variants previously reported to be pathogenic.

Clinical FTD: a converging downstream result of manifold pathways?

Our findings of both classic and nonstandard dementia genes as causing clinical FTD syndromes also provide important insights into the molecular pathophysiology of FTD. They indicate that genetic insults contributing to this pathophysiology occur not only in pathways commonly linked to FTD (e.g., TDP-43, progranulin), but also in a wide variety of other pathways, e.g., mitochondrial (CHCHD10), amyloid (PSEN1, PSEN2), lipofuscinosis (CTSF), and cholesterol homeostasis (CYP27A1) pathways. This suggests that clinical FTD might be the converging downstream result of manifold pathways, arising from a delicate susceptibility of frontotemporal brain networks to genetic insults in these pathways. This notion is supported by recent gene coexpression network studies demonstrating that multiple disease mechanisms contribute to the pathology in the frontotemporal cortex in FTD subjects.40

Some of the defects in these pathways might be overlapping or converging when leading to the shared downstream clinical syndrome of FTD. Our findings provide preliminary indications that reductions in Aβ1-42 or progranulin might represent such partial overlaps or at least concomitant contributions to FTD disease etiology. Aβ1-42 reductions were observed not only in PSEN mutation carriers (where they would be expected), but also in GRN mutation carriers; and progranulin reductions were observed not only in GRN mutation carriers (where they are expected), but also in a CHCHD10 mutation carrier. This notion of progranulin reduction as a shared feature across FTD subjects receives broader support from our recent finding that progranulin reductions are common even in FTD subjects without GRN mutations.9

In summary, we present here a genetic in-depth study of clinical FTD, unraveling mutations and CNVs in several genes hitherto not linked to FTD and, moreover, providing relative frequencies of a strictly consecutive series with clinical FTD. It demonstrates that genetic defects in various pathways contribute to the pathogenesis of clinical FTD, even including 11% of seemingly sporadic subjects. This suggests that comprehensive in-depth genetic screening might be considered in all FTD patients, even if family history is negative. Moreover, these findings indicate that clinical FTD is the converging downstream result of genetic insults in manifold pathways, arising from a delicate susceptibility of frontotemporal brain networks to insults in these pathways.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Else-Kröner Fresenius Stiftung (to M.S.), the Hans und Ilse-Breuer Stiftung (stipend to A.R.) the EU Joint Programme-Neurodegenerative Diseases JPND project RiMod-FTD by contribution of the BMBF (to P.H.), the NOMIS Foundation (to C.H. and P.H.), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the framework of the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (EXC 1010 SyNergy).

We thank the included subjects and their families for their valuable contributions and for supporting this research, and Ingeborg Krägeloh-Mann, Samuel Groeschel, and Stefanie Beck-Wödl for discussing with us the subject with the ARSA p.T410I variant. DNA samples were obtained from the Neuro-Biobank of the University of Tübingen, Germany (http://www.hih-tuebingen.de/ueber-uns/core-facilities/biobank/). This biobank is supported by the University of Tübingen, the Hertie Institute, and the DZNE. A section of the results provided in this paper were presented as a poster at the 10th International Conference on Frontotemporal Dementias, Munich, Germany; 31 August–2 September, 2016.

Footnotes

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/gim

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

M.S. has received honoraria from Actelion Pharmaceuticals, unrelated to this work. C.H. is an adviser to F. Hoffmann–La Roche. The authors declare no conflict of interest related to the present work.

Supplementary Material

References

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998;51:1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011;76:1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossenkoppele R, Pijnenburg YA, Perry DC et al. The behavioural/dysexecutive variant of Alzheimer's disease: clinical, neuroimaging and pathological features. Brain 2015;138(Pt 9):2732–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol 2006;59:952–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley T, Rohrer JD, Mead S, Revesz T. Review: an update on clinical, genetic and pathological aspects of frontotemporal lobar degenerations. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2015;41:858–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalls MA, Bras J, Hernandez DG et al. NeuroX, a fast and efficient genotyping platform for investigation of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36:1605.e1607–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyatake S1, Koshimizu E1, Fujita A1 et al. Detecting copy-number variations in whole-exome sequencing data using the eXome Hidden Markov Model: an 'exome-first' approach. J Hum Genet 2015;60:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke C, Gillardon F, Deuschle C et al. Cerebrospinal fluid progranulin, but not serum progranulin, is reduced in GRN-negative frontotemporal dementia. Neurodegener Dis 2016;17:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik M, Born C, Rominger A et al. Targeted high-throughput sequencing identifies a TARDBP mutation as a cause of early-onset FTD without motor neuron disease. Neurobiol Aging 2014;35:1212.e1211–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik M, Maetzler W, Grehl T et al. Screening in ALS and FTD patients reveals 3 novel UBQLN2 mutations outside the PXX domain and a pure FTD phenotype. Neurobiol Aging 2012;33:2949.e2913–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutihac R, Alegre-Abarrategui J, Gordon D et al. TARDBP pathogenic mutations increase cytoplasmic translocation of TDP-43 and cause reduction of endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2)(+) signaling in motor neurons. Neurobiol Dis 2015;75:64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orru S, Coni P, Floris A et al. Reduced stress granule formation and cell death in fibroblasts with the A382T mutation of TARDBP gene: evidence for loss of TDP-43 nuclear function. Hum Mol Genet 2016;25:4473–4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurin N, Brown JP, Morissette J, Raymond V. Recurrent mutation of the gene encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1/p62) in Paget disease of bone. Am J Hum Genet 2002;70:1582–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Guerreiro R et al. SQSTM1 mutations in French patients with frontotemporal dementia or frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA neurol 2013;70:1403–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok CT, Morris A, de Belleroche JS. Sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1) sequence variants in ALS cases in the UK: prevalence and coexistence of SQSTM1 mutations in ALS kindred with PDB. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22:492–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannwarth S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Chaussenot A et al. A mitochondrial origin for frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis through CHCHD10 involvement. Brain 2014;137(Pt 8):2329–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raux G, Gantier R, Thomas-Anterion C et al. Dementia with prominent frontotemporal features associated with L113P presenilin 1 mutation. Neurology 2000;55:1577–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwendraat C, Wilke C, Jansen IE et al. Pilot whole-exome sequencing of a German early-onset Alzheimer’s disease cohort reveals a substantial frequency of PSEN2 variants. Neurobiol Aging 2016;37:208.e211–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Kubota S, Ujike H, Ishihara T, Seyama Y. A novel Arg362Ser mutation in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene (CYP27): its effects on pre-mRNA splicing and enzyme activity. Biochemistry 1998;37:15050–15056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Dahl HH, Canafoglia L et al. Cathepsin F mutations cause type B Kufs disease, an adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:1417–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comabella M, Waye JS, Raguer N et al. Late-onset metachromatic leukodystrophy clinically presenting as isolated peripheral neuropathy: compound heterozygosity for the IVS2+1G—>A mutation and a newly identified missense mutation (Thr408Ile) in a Spanish family. Ann Neurol 2001;50:108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder SD, van der Flier WM, Verheijen JH et al. BACE1 activity in cerebrospinal fluid and its relation to markers of AD pathology. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;20:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch N, Baker M, Crook R et al. Plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutation status in frontotemporal dementia patients and asymptomatic family members. Brain 2009;132(Pt 3):583–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Glionna M, Franzoni M, Binetti G. Low plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 2008;71:1235–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottier C, Bieniek KF, Finch N et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals important role for TBK1 and OPTN mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration without motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol 2015;130:77–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattante S, Le Ber I, Camuzat A et al. TREM2 mutations are rare in a French cohort of patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:2443.e2441–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majounie E, Renton AE, Mok K et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Guerreiro R, Vandrovcova J et al. The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 2009;73:1451–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee J, Gijselinck I, Van Mossevelde S et al. TBK1 Mutation Spectrum in an Extended European Patient Cohort with Frontotemporal Dementia and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Hum Mutat 2017;38:297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzu P, Van Swieten JC, Joosse M et al. High prevalence of mutations in the microtubule-associated protein tau in a population study of frontotemporal dementia in the Netherlands. Am J Hum Genet 1999;64:414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijselinck I, Van Mossevelde S, van der Zee J et al. Loss of TBK1 is a frequent cause of frontotemporal dementia in a Belgian cohort. Neurology 2015;85:2116–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaivorinne AL, Kruger J, Kuivaniemi K et al. Role of MAPT mutations and haplotype in frontotemporal lobar degeneration in Northern Finland. BMC Neurol 2008;8:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie S, Chen G, Cao X, Zhang Y. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyant-Marechal L, Verrips A, Girard C et al. Unusual cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with fronto-temporal dementia phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 2005;139A:114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Kimura A, Chen W et al. Frontal lobe dementia with abnormal cholesterol metabolism and heterozygous mutation in sterol 27-hydroxylase gene (CYP27). J Inherit Metab Dis 2001;24:379–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio R, Moro F, Pestillo L et al. Pseudo-dominant inheritance of a novel CTSF mutation associated with type B Kufs disease. Neurology 2014;83:1769–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bras J, Djaldetti R, Alves AM et al. Exome sequencing in a consanguineous family clinically diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease identifies a homozygous CTSF mutation. Neurobiol Aging 2016;46:236.e231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzl JK, Mori K, Damme M et al. Common pathobiochemical hallmarks of progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:845–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R, Forabosco P, Vandrovcova J et al. Frontotemporal dementia: insights into the biological underpinnings of disease through gene co-expression network analysis. Mol Neurodegener 2016;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.