This is the tenth article in our series on population healthcare.

The mission of healthcare is not only to improve the health of individuals but also to improve population health. The focus in years past has been on reducing mortality and increasing life expectancy, but increasingly the focus is shifting to healthy life expectancy, although reducing the eight-year difference in life expectancy between the wealthiest and the most deprived sectors of our population remains a top priority.

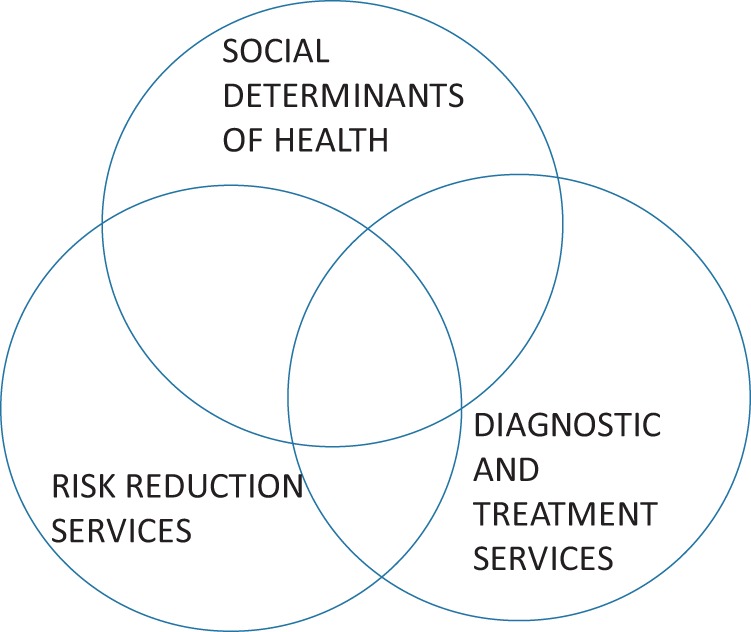

There are three factors that determine the health of a population, whether measured in terms of life expectancy or healthy life expectancy. These are:

the social environment, for example, the degree of inequality and the prevalence of poverty and bad housing;

public health risk reduction services, for example tobacco taxation, smoking cessation support, immunisation and screening;

the diagnostic and treatment services for that population, their healthcare.

When listed, it is important to remember that there is no agreed order of importance – although the evidence is stronger that the social determinants of health are the most influential – the key fact is that they are intrinsically linked:

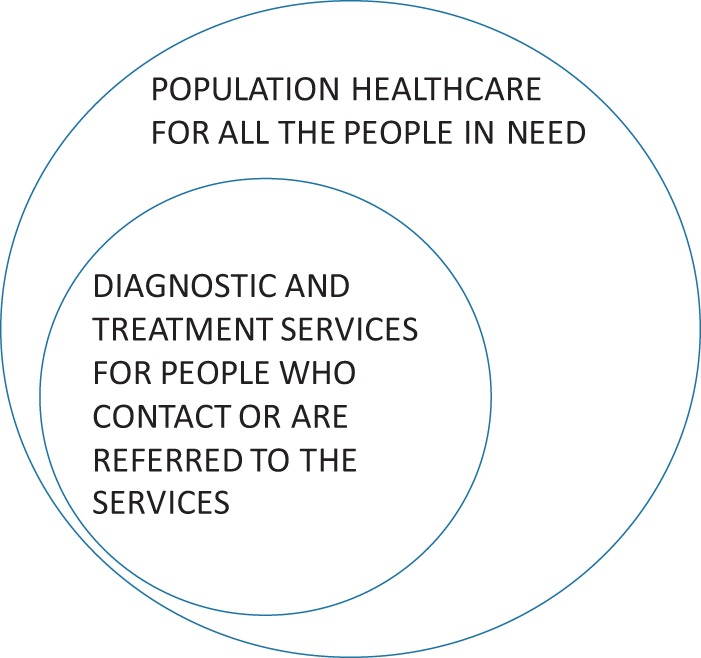

The diagnostic and treatment services for that population need to be judged by not only the effectiveness, quality and safety of the clinical services delivered to the people who make contact with the service, often called the patients, but also by the effectiveness with which the service relates to and serves all the people in need in the population as well as the cost. This embraces the clinical service but is a broader approach called population healthcare.

With need and demand growing faster than resources, it is crucial to take into account the needs of the entire population in decision-making if value is to be optimised.

The development of the new approach requires cultural change not bureaucratic reorganisation. It is, however, important to acknowledge the contribution that bureaucracy has made to health improvement.

The bureaucratic triumph

The Northcote-Trevelyan reforms of the English Civil Service were of fundamental importance in the first healthcare revolution, the public health revolution. From an era of nepotism and corruption, a modern bureaucracy emerged and without an uncorrupt and efficient bureaucracy, the prevention of water-borne diseases would have been impossible. In the second half of the 19th century, many countries reformed their public services allowing public health measures to be implemented. Whether the bureaucracy chose a direct tax-based approach as in the United Kingdom or went down the insurance route as Bismarck did in Germany, it was bureaucracy that improved health, together with the railways. Before the railway system, it was very difficult for the central government to control a wayward local authority, but when it took only a few hours to travel from London to the furthest part of the country to discipline or replace a local authority, it was possible to implement national public health policies.

In the 19th century, the present pattern of services for diagnosis and treatment also emerged with the delivery of healthcare through four major types of institution – general practice, hospital care, specialised mental health services and domiciliary health and social care. What developed was an archipelago of distinct islands of care as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Healthcare Archipelago.

From about 1960 on, dramatic changes took place which can be considered to comprise a second healthcare revolution with new interventions arising such as transplantation, hip replacement and chemotherapy.

The bureaucracies that ran health services became more effective and more efficient as part of this revolution and in parallel a large industrial complex grew developing new drugs and equipment, but the basic pattern of delivery is virtually unchanged since the 19th century. The modern bureaucracies are epitomised by the great buildings of the modern hospitals, which were in many cities the landmark building expressing the triumph of healthcare, like the railway stations were the landmark buildings of the first industrial revolution. The bureaucracies became increasingly sophisticated introducing styles of management that encouraged evidence-based decision-making and quality improvement, and all of this in an era in which resources were growing steadily in every developed country.

This has been a wonderful period, but we are now at the end of the second healthcare revolution.

More of the same is necessary but not sufficient

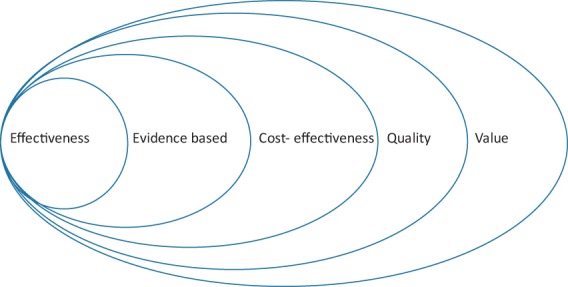

It is vitally important that we continue with the four activities that have dominated decision-making in the last 50 years, namely

prevention, the highest value healthcare;

evidence-based decision-making, namely decisions based on strong evidence from high-quality research epitomised by the work of NICE;

quality and safety improvement, learning from industry to improve outcomes;

cost reduction.

Evidence-based decision-making and quality improvement both increase the probability of a good outcome and increase efficiency but even increased efficiency is not sufficient to allow us to meet the challenge posed by increasing need and demand in an era in which there will not be a commensurate increase in resources. However, the challenge we face cannot be met by increased investment alone, although the crisis created by Lehman Brothers collapse and its consequences has played a part in revealing the need for a new paradigm.

The ideas, first promoted by Wennberg1 and Donabedian,2 that there could be overuse healthcare or medicine took some time to be accepted. Fortunately in the first decade of the 21st century, the issue of overuse – over-diagnosis and over-treatment – emerged as a key issue led by a number of different groups, for example the British Medical Journal’s Too Much Medicine Campaign, the Choosing Wisely Campaign,3 the work done in Dartmouth College in New Hampshire4,5 and developments in the UK, notably Prudent Healthcare in Wales, Realistic Medicine in Scotland and in England the programmes called RightCare and GIRFT (Getting It Right First Time).

The evolution of value-based healthcare

The work of Wennberg and Donabedian raised the issue of overuse and unwarranted variation, but without the disruption resulting from the global financial collapse, it is probable that healthcare would have carried on at least for another decade based on the bureaucratic structure, inherited from the 19th century and developed in the 20th century. More of the same is essential, so we still need evidence-based decision-making and quality improvement but although low-quality care is of low value, high-quality care is not necessarily of high value. We need to shift from measuring healthcare only by the impact on the patients who reach healthcare but also to focus on the impact of our investment on the population as a whole to focus on value. As always, the new paradigm embraces and enfolds the previous paradigms.

There are two aspects of value – population and personalised

From the point of view of the population served, it is necessary to optimise both the allocation and use of resources.

Allocative value or allocative efficiency, the economists’ term, is determined by the outcome of resource allocation to different subgroups of the population, people with cancer or people with mental health problems, for example. This is one reason why the term value has a different meaning in the United States where resources are not explicitly allocated in this way. The second difference between the United States and countries with universal health coverage is that the value in these countries has to include not only the efficiency with which patients are treated – outcomes related to costs – but also the possibility that some people in need in the population served may not have been referred. Sometimes they are in even greater need than those who have been referred and there are often social reasons related to referral, with poor people less likely to be referred, of which the most significant is deprivation. Payers in countries with universal health coverage have to ensure that their assessment of value includes equity.

Personalised value is the second aspect of value. Population healthcare and personalised value are two sides of the one coin. As we increase the amount of resources in a population group, not only does the return on investment for the population as whole change as people who are less severely affected are treated, because there is diminishing return in terms of benefit but increasing harm from the inevitable side effects of even high-quality healthcare balance which is a phenomenon first described by Donabedian in 1980. The individual person offered treatment by the individual clinician also changes with treatment being offered to individuals who are less severely affected. For such an individual, the maximum benefit that they could enjoy is less than the benefit enjoyed by someone who is severely affected, but the risk and magnitude of harm are the same.

Good bureaucracy is necessary but not sufficient

Throughout the 20th century, there has been increasing criticism of bureaucracy with the adjective of bureaucratic now being a term of contempt. However, as Charles Perrow has emphasised,6 bureaucracies have a very important function to play and only those who have lived in countries without uncorrupt and efficient bureaucracies can appreciate the importance of a good bureaucracy, providing it sticks to the type of tasks of which bureaucracies have been designed, for example the fair and open employment of staff and the management of money. What is clear is that bureaucracies are not the organisational form best suited to function such as

delivering services to all the people in a population with headache or epilepsy; or

ensuring that everyone in the last year of life receives sufficient, compassionate high value care.

For these, a new form of organisation is required – a complex adaptive system delivered by a network.7,8 The 20th century was the century of the hospital and the health centre; the 21st century is the century of the system and the network. The 20th century was the century of the doctor; the 21st century is the century of the person we call the patient, and digital opportunities play a key part in both these transitions as part of the third healthcare revolution.9

The future of healthcare is not hospital-based or primary care-based, neither is it genomic or digital; it is personalised and population healthcare.

| Here are the 10 key principles of this new approach. |

| • The primary focus of a 21st century health service is value. |

| • Value embraces effectiveness, efficiency, quality and safety and is determined by both the allocation and use of resources. |

| • Value is subjective and the most important perspectives of value are the perspectives of the population served and of the individual, which are two sides of the same coin. |

| • Personalised healthcare is the other side of the same coin as population healthcare. |

| • Effective bureaucracies are essential for the good governance of resources but neither bureaucracies nor markets can tackle complex problems and need to be complemented by systems and networks. |

| • The delivery of care will be through population-based programmes and, within each programme, systems. |

| • A system is a set of activities with a common set of objectives and an annual report presented to the people with the problem. |

| • Systems are delivered by networks of clinical and patient organisations. |

| • The optimum population size is determined by the prevalence of the condition and the need for expensive capital or specialist skills. |

| • Clinicians need to be the stewards of the resources, accountable to the population served and not just to the patients who have been referred. |

The creation of population healthcare needs neither political fiat not bureaucratic reorganisation of the health service. It needs transformational leadership, defined first by James McGregor Burns

the great American political scientist (and biographer of F.D. Roosevelt), James McGregor Burns. In his magisterial Leadership (first published in 1978) he drew the distinction between ‘transactional leadership’, which was all about interpersonal influence and persuasiveness, and ‘transformational leadership’ which concerned destinations as well.10

The destination is clear – higher value for both populations and individuals, so too is the route.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Guarantor

MG.

Contributorship

MG did the first draft.

Acknowledgements

None

Provenance

Not commissioned; editorial review

References

- 1.Wennberg JH. Tracking Medicine. A Researcher’s Quest to Understand Health Care, New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donabedian A. Explorations in Quality Assessment & Monitoring (3 vols), Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 3.www.choosingwisely.co.uk (last checked 22 December 2017).

- 4.Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ 2010; 341: c5146–c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Mulley A, Chris Trimble T, Glyn Elwyn G. Patients’ Preferences Matter; Stop the Silent Misdiagnosis, London: King’s Fund, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrow C. Complex Organizations: A Critical Essay, 3rd edn New York: McGraw-Hill Inc., 1972, pp. 147–147. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney K. Complexity in Primary Care. Understanding its Value, Oxon: Radcliffe Publishing, 2006, pp. 71–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JAM. How to Build Healthcare Systems, Oxford: Offox Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castells M. The Network Society, Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mant A. Intelligent Leadership, London: Allen & Unwin, 1999, pp. 24–24. [Google Scholar]