Abstract

Currently, over 1 million Syrian and Palestinian refugees have fled Syria to take refuge in Lebanon. Among this vulnerable population, elder refugees warrant particular concern, as they shoulder a host of additional health and safety issues that require additional resources. However, the specific needs of elder refugees are often overlooked, especially during times of crisis. Our study used a semi-structured interview to survey the needs of elder refugees and understand their perceived support from Lebanese fieldworkers. Results indicate a high prevalence of depression and cognitive deficits in elder refugees, who expressed concerns surrounding illness, loneliness, war, and instability. Elders highlighted the importance of family connectedness in fostering security and normalcy and in building resilience during times of conflict. Elders spoke of their role akin that of the social workers with whom they interacted, in that they acted as a source of emotional support for their communities. Overall, this study clarifies steps to be taken to increase well-being in elder refugee populations and urges the response of humanitarian organisations to strengthen psychological support structures within refugee encampments.

Keywords: Syria, elders, refugees, Lebanon, psychosocial, needs assessment, empathy

1. Introduction

After accepting more than 1 million refugees from Syria since the beginning of the Syrian conflict, Lebanon now has the highest concentration of refugees per person in the world (M.T., 2015). Though the number of elder refugees in Lebanon remains unknown, global reports show older persons to constitute 8.5% of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) Population of Concern (Strong, Varady, Chahda, Doocy, & Burnham, 2015). This number is, in fact, greater than the estimated over-60 population of Syria, which has been recorded at 5.8% (International Programs, n.d.). These statistics bring about unique concerns, as older persons are most vulnerable during displacement and face a variety of unique stressors during times of conflict due to age-specific disadvantages and disabilities (Shayda, Sayah, Strong, & Varady, n.d.). Among those who migrate, impairments in mobility, vision, hearing, memory, and cognition are common (Gillam, 2014). Due to pre-existing chronic ailments, elders often lack the strength to perform physical work and can grow dependent on their younger family members (Bazzi & Chemali, 2016).

It is exactly in these perilous times that one must recognise the crucial role elders play in Middle Eastern society, and the extent to which the Syrian community relies on them (Bazzi & Chemali, 2016; Kariuki, 2015; ‘Sahrawi and Afghan Children’, n.d.). Middle Eastern cultures prioritise the family in their predominantly patriarchal culture even in times of peace, with elders serving as the pillar of these extensive family units. In understanding the leadership role elder refugees hold in family networks, one expects that elders would engage in similar positions for refugee communities. The elders’ roles benefit these communities while providing a sense of agency to elders, especially for those who have lost connections in their family networks (Bazzi & Chemali, 2016). Given elders’ wisdom and the community’s respect of their ideas, elders have the ability to play a crucial role in peace building and constructive cooperation with host communities. Still, we know very little about elder refugees’ needs. As we continue to support elders in building leadership roles, it is imperative to conduct research to assess and address their needs and to attend to their rights (Bazzi & Chemali, 2016; ‘Forgotten Voices’, 2013; Strong et al., 2015).

Following the influx of Syrian refugees into Lebanon, the Lebanese Ministry of Social Affairs (MOSA) and its social and fieldworkers provided critical humanitarian services within refugee encampments. These services included distributing food, tents, heating materials, blankets, and clothing to help alleviate suffering in refugee communities (‘Syria Emergency’, n.d.). In addition to providing resources, social workers help refugees to register with UNHCR and work towards permanent resettlement. As such, this study initially sought to assess the feasibility of stress reduction and mindfulness training for social and fieldworkers in Lebanon, training a host of social workers from different regions across Lebanon (‘The Benson Henry Institute’, n.d.; Chemali et al., 2017). In doing so, this work uncovered hidden realities pertaining to the needs of elder refugees, as many fieldworkers sought to uplift the voices of this vulnerable population. During one field visit, elder refugees were chosen as a target for trainees’ fieldwork assignment. In understanding the important role elders play in refugee communities, this assessment sought to examine four distinct factors: first, the unmet needs of elder refugees; second, the overall quality of life for elder refugees; third, the connection – or lack thereof – between refugees and social workers; and fourth, the role of social workers in refugee communities, as it is perceived by elder refugees.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

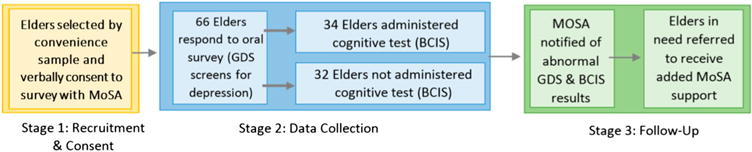

In this study, elderly participants were recruited from refugee encampments in El-Marj and Bar Elias in Lebanon. The social and fieldworkers administered semi-structured qualitative surveys and cognitive tests to assess the needs of elder refugee communities (see Appendix). As part of the implementation focus of this study, elders whose testing revealed symptoms of depression or cognitive impairment were referred to receive further support from MOSA workers, a measure to which they consented at the start of the study (Figure 1). Participants were not compensated for their involvement in this study. The Lebanese Ministry of Social Affairs, Syrian Project committee, and the Institutional Review Board at Massachusetts General Hospital (2015P000489) approved the study (see Appendix).

Figure 1.

Study design.

2.2. Study sample

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling in the form of word of mouth. MOSA fieldworkers utilised encampment chiefs as intermediaries; the chiefs announced the project and asked interested elders to enlist directly with the MOSA regional field director. Elders were defined as members of the refugee community who self-identified as at least 65 years old. Beyond this age requirement, this study had no exclusion criteria. In total, 66 elders expressed oral consent to take part in the study.

2.3. Data collection procedures

Data collection occurred throughout the month of December 2015. Following elders’ verbal consent with MOSA, MOSA fieldworkers who had been trained in mindfulness procedures administered semi-structured oral surveys, supervised by an on-site psychiatrist. Participant responses were recorded manually by the fieldworkers and later translated from Arabic to English. Roughly half of participants also completed a brief cognitive test following this survey, which was administered by an on-site psychiatrist. Participants were selected for this assessment in an alternating fashion, with every other participant receiving the test. Prior to the survey, the psychiatrist and the MOSA team introduced themselves to the elders and briefed them on the plan for the day, describing that MOSA trainees would assess their needs and refer them to additional support if necessary. The team also introduced the survey and cognitive battery, noting that the visits would be timed. Following this introduction, they began conducting the surveys. Visits were conducted privately in each participant’s respective tent or personal area, and lasted between 10 and 15 minutes in total. Following each visit, MOSA fieldworkers were debriefed on elders who required additional evaluation for their mood and cognitive function, as demonstrated in the survey and cognitive testing. Elders with demonstrated depressive symptomatology and cognitive difficulties were referred to MOSA workers to receive heightened community and interpersonal support, the furthest extent of mental health care possible in a system that does not often prioritise or address mental health needs. Based on the refugees’ reports and comments, recommendations were submitted to MOSA to address these gaps and attend to elder refugees’ well-being.

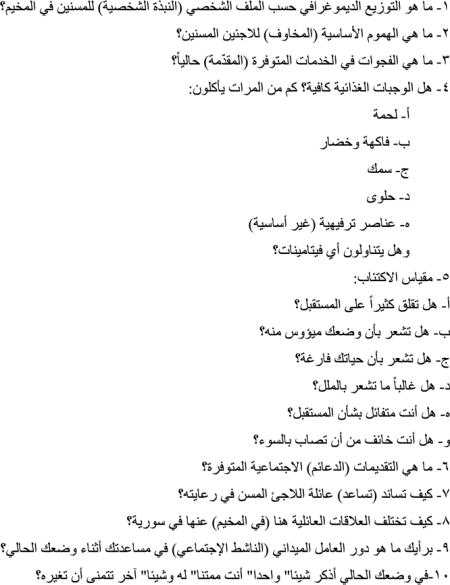

2.4. Study measures

Data were collected using a semi-structured interview, which included qualitative and quantitative questions on participants’ personal well-being and deficits in their care, regarding both social support and official humanitarian services. Six questions were derived from an Arabic translation of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), an assessment of depressive symptomology that is validated in Arabic and often implemented in comprehensive evaluations of geriatric health (Chaaya et al., 2008). General questions and those related to the GDS were administered to all participants. Half of the participants were also tested using the Brief Cognitive Impairment Scale (BCIS), a short assessment battery for executive functioning, language, and memory. The BCIS is often used as a screening tool for moderate to severe cases of dementia and was chosen for this study due to its utility as a basic cognitive screen for participants with limited education (Allen, 2011). As this measure was translated to Arabic, it was also overviewed by MOSA to ensure that the language was culturally relevant and coherent. Following MOSA’s overview, it was translated back to English by an official interpreter to ensure that the meaning of each question was upheld. Both the GDS and BCIS were chosen to evaluate quality of life for elder refugees, as depression and cognitive impairment are two aspects of physical and mental health that impact well-being (Abrams, Lachs, McAvay, Keohane, & Bruce, 2002).

2.5. Data analysis

All quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23.0. Descriptive statistics including frequencies/percentages and means/standard deviations were computed for all study variables, and all continuous variables were assessed for normality. Bivariate relationships were investigated using an independent t test, Pearson chi-square test, and a one-way analysis of variance. Comparisons were conducted using Pearson chi-square test for dichotomous variables and independent samples t tests and one-way analysis of variance for interval-level variables.

For the qualitative data, a summative content analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. First, researchers’ interview notes were grouped according to interview question and translated from Arabic to English. As many elder refugees discussed similar themes under each question, overlapping responses were examined and quantified, and concurrently ranked from most to least common. Using the quantified scores for each response, word clouds were generated with qualitative software to visualise these data. Following this quantification of themes, outliers in the data were examined as part of a wider analysis of the underlying context for these data. Final interpretations of the qualitative data were the product of analyses regarding both the content and context of interview responses.

2.5. Limitations

The primary limitations of this study were the limited convenience sample and the lack of strong training among MOSA fieldworkers on qualitative methods. As this study only sampled elders from two different refugee encampments, these data may not reflect the experiences faced in all encampments across Lebanon. Hence, one must exercise caution in generalising these results to all refugees. This is especially true for elder refugees, for whom minimal research has been done to date. In addition to this, the study only recruited elders who directly expressed their interest in the study to MOSA staff. Not all elders were screened for this study, and even those who were recruited were not forced to answer every question asked. As such, non-response bias may affect the validity of these data. It is possible that the elders who responded to these questions were those most vocal against fieldworkers, or, conversely, most lenient with them. This study was also limited by the lack of registration among refugees in these encampments. Recruitment inherently favours registered refugees, as these refugees are eligible for support that unregistered refugees are not and therefore have greater motivation to discuss resource distribution. However, numerous unidentified factors may further impede or facilitate non-registered refugees’ participation in research. In either case, we note that this sample may not accurately reflect the demographics of each encampment. For many elder refugees, cognitive impairments were another limiting facet of this study. Limited cognition may have biased our results, as some of the study’s questions may have been answered without being fully understood. Several study questions also relied on selective memory processes to quantify resources, which may have been lacking in some elders. Additionally, fieldworkers’ limited training in qualitative methods constrained our ability to synthesise and analyse the data gathered.

Lastly, as social workers themselves collected this information, the effect of social desirability should not be ignored in one’s interpretation of these data. This phenomenon is highly relevant for the sensitive content of the study’s survey, specifically in questions regarding the role of social workers. It is a basic human instinct, particularly in vulnerable populations, to withhold negative or unwelcome responses in favour of positive ones. However, it should be noted that roughly 25% of responses about social workers indicated an unfavourable view, signifying that some respondents were comfortable sharing negative feedback. Overall, the dearth of available research in this setting is what impedes on our ability to objectively compare our results.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The average overall age of participants was 65.88, ±7.26 years. 59.1% of participants identified as female, and 40.9% identified as male. Many participants reported being currently or previously married, with 62.2% married at the time of the study. Participants travelled to Lebanon from 14 distinct regions of Syria, including Homs, Rural or Central Idlib, and Rural Damascus. Other regions of origin not listed in Table 1 include Golan, Jouber, Kassir, Hajar Aswad, Daraya, Alza’, Sayeda Zaynab, and Douma.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Total participants (N = 66) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| (SD) | |

| Age | 65.88 (7.26) (N = 66) |

| Geriatric Depression Score (X/6) | 4.82 (1.227) (N = 66) |

| BCIS (X/15) | 9.32 (3.062) (N = 34) |

| N (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 39 (59.1%) |

| Male | 27 (40.9%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 23 (62.2%) |

| Widowed | 9 (24.3%) |

| Divorced | 3 (8.1%) |

| Single | 2 (5.4%) |

| Region | |

| Homs | 15 (31.3%) |

| Idlib/Rural Idlib | 9 (18.8%) |

| Rural Damascus | 6 (12.5%) |

| Cham | 5 (10.4%) |

| Bab Amir | 3 (6.3%) |

| Other | 10 (20.8%) |

| UNHCR registration status | |

| Registered | 31 (59.6%) |

| Refused by UNHCR | 13 (25.0%) |

| Not registered | 8 (15.4%) |

| Level of education | |

| Illiterate | 18 (78.3%) |

| Some education | 5 (21.7%) |

While the majority of participants had attempted to register with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), only 59.6% were registered, with many having been refused registration due to the lack of official documentation. Literacy also varied among participants, with 78.3% illiterate and the remaining having only one to five years of education. In a baseline survey using the GDS (scored from 0 to 6, with >3 signifying depressive symptoms), participants scored an average of 4.82 ± 1.227. In the BCIS (scored from 0 to 15, with 15 representing normal mental status) participants had an average cognitive score of 9.32 ± 3.062 (see Table 1).

3.2. Quantitative data

There were no significant mean differences on the GDS between males and females (t = 0.628, p = .532), literacy levels (t = −0.340, p = .737), and registration status (F = 1.826, p = .172). When examining the BCIS, there was a significant mean difference between cognitive scores and gender (t = −3.376, p = .002) where men had statistically significant higher mean cognitive scores than woman 11.42 (2.594) vs. 8.18 (2.811). We examined literacy levels by gender and these two variables were not significantly related (Fisher’s exact test = .608, p = .605). There was also no significant mean difference between the BCIS and literacy levels (t = −1.040, p = .311) or with registration status (F = 1.208, p = .317).

3.3. Qualitative data

The following questions and themes from the semi-structured interview were examined in the qualitative analysis:

How often do elders receive different food and luxury resources?

What are elders’ greatest concerns?

What services and resources are available to elder refugees? What are not?

From elders’ points of view, what is the role of social workers in their current situation?

How does elders’ support in Lebanon differ from their support in Syria?

In elders’ current situations, what is one thing they are grateful for? What is one thing they would change?

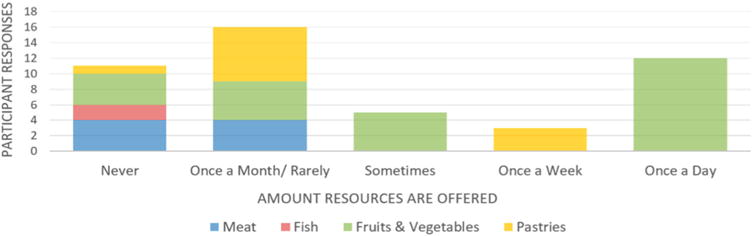

As part of the semi-structured interview, elders provided information on the services and resources available to their family or household. Fruits and vegetables were the only food resource available daily, and even these were only available to a handful of participants questioned. While pastries and meat were reported to be offered on rare occasions, several elders reported never receiving these resources, and no participant reported ever-receiving fish (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Availability of food resources.

Despite the high prevalence of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke among elder Syrian refugees in Lebanon (Strong et al., 2015), participants reported little to no distribution of medications. While vitamins were seldom available to elders, a handful of participants did report receiving calcium and iron supplements. Elders were also provided with a few luxury items, such as television, playing cards, and tobacco. None of these items were available at all times, however, and all items were only accessible to a minority of refugees surveyed.

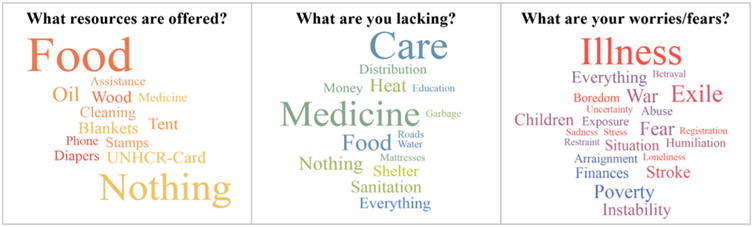

When asked about the resources available to them, many elders described food as their primary source of aid, also citing the availability of grains, cans, and food stamps. However, several discussed that food resources were ‘not sufficient’, with the second largest majority of participants reporting having access to ‘nothing’ or ‘barely nothing’ since arriving in Lebanon. While a handful of participants mentioned receiving items for heat and shelter, only one participant discussed ever-receiving medication, and even this was on rare occasions. When asked about their primary needs, the majority of elders surveyed discussed a need for personal care items or medication. This need reflected the primary fears of elder refugees, whose main worries revolved around illness, stroke, and death in exile. Taken together, elders’ fears of illness, lack of medication, and heightened prevalence of health disorders represent a major area for improvement in humanitarian efforts. Financial instability also ranked among the primary sources of anxiety for participants, as many discussed a lack of resources despite the aid provided by UNHCR. Several cited distribution problems as the cause of these issues; while some elders did receive the food and shelter they so urgently required, others with equal need did not have access to the same resources (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Worries, needs, and available resources.

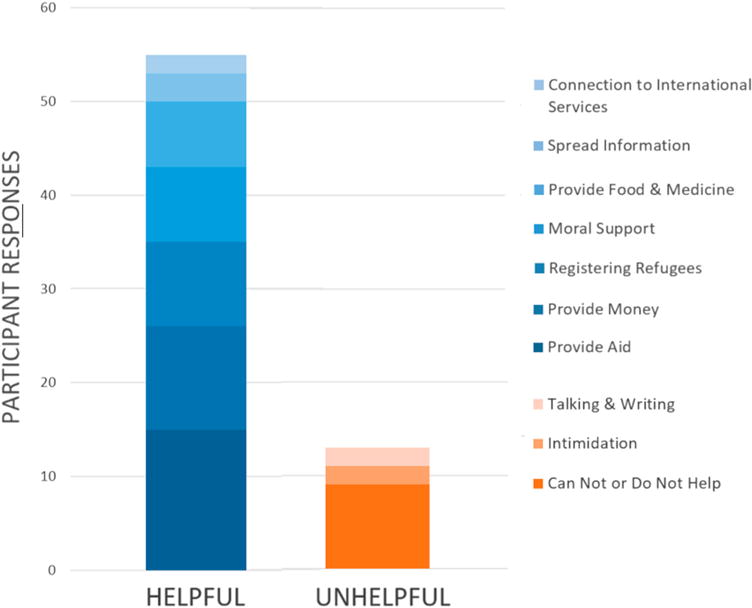

Despite issues with distribution and the limited availability of resources, the majority of participants held social workers in high esteem. Many cited the helpfulness of social workers in providing access to money, food, and medicine when available, while others reported workers to have a vital role in registering refugees with UNHCR and providing general moral support. Those who disapproved of social workers largely agreed that, due to the overall challenges of the Syrian refugee crisis, social workers occupied a role in which it was ‘impossible to help’, with one claiming that ‘some help, [but] some don’t’ (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Perception of the role of social workers in helping elder refugees.

During the qualitative interview, participants were also asked to compare their previous life in Syria with their current situation as a refugee in Lebanon. Many reflected fondly on the familial connections and support they received in Syria, discussing how the neighbourhoods and communities in which they lived provided them with adequate personal, medical, and emotional support in their old age. One elder described the foreign nature of social assistance in Lebanon, saying, ‘We don’t need anyone when in Syria.’ As another described, ‘We worry for each other.’ Upon elders’ displacement in Lebanon, many participants were separated from these familial and community connections. As a result, participants discussed loneliness and a lack of socialisation as the hallmarks of their time in Lebanon, with one claiming that ‘here, I see no one’. Elder refugees did not just lose their homes when forced to leave Syria; they lost their medical and social support structures, thrown into a turbulent and unfamiliar community through which they receive limited access to external support.

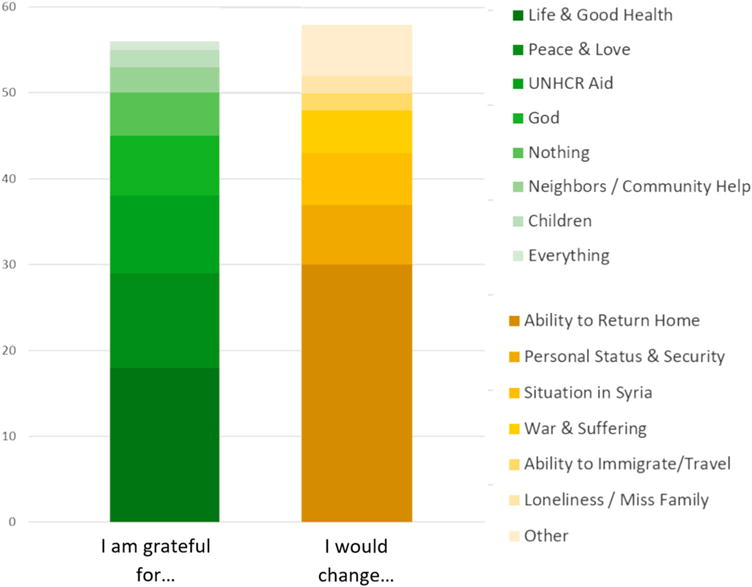

At the end of each interview, participants were asked to describe one thing they were grateful for, as well as one thing they would change. Participants offered many sources of gratitude; elders were grateful for the aid provided to them through UNHCR, for God, and, primarily, for their lives and good health. When asked what they would change, more than half wished simply to return home to Syria. Others wished to change the situation in Syria, the overall atmosphere of war and suffering, and their personal status and security. Again, the theme of family connections surfaced, with one participant wishing for ‘my security and that of my children’ and another simply grateful that ‘my children are next to me’ (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

What elder refugees are grateful for and what they would change.

Overall, familial connections were among the most important aspects of elders’ daily lives. Elders enjoyed telling stories to family members, participating in simple chores, and fostering a sense of normalcy for their community members. The more loving and supportive the family members were, the more resilient and confident the elders. Elders spoke of their role in the community as being similar to that of the social workers with whom they interacted. Although they expressed gratitude to the social workers for providing them with tangible services needed in their everyday lives such as tents and food, they expressed a desire to be a source of emotional support and a community cornerstone for those around them.

4. Discussion

This research is one of the few studies targeting elder refugees, one of the most vulnerable populations among refugees. This work uncovers the myriad fears of elder refugees, not least among them being illness and war. The disintegration of family life is of major concern to elders, who often struggle personally with displacement-related disruption of interpersonal relationships. Clear issues also surfaced regarding uneven distribution of food and medications in refugee encampments, which raises the question if similar issues are present in other encampments across Lebanon. The noted lack in access to medications is particularly alarming to them, as illness and death, especially dying in exile, rightfully ranked among elders’ primary fears. Participants expressing such concerns were given access to information on how to access health services and had their concerns referred to the MOSA Syrian Project Desk. Additionally, while the majority of elders surveyed held social workers in high esteem, a notable portion did regard their work to be ineffectual. Taken together, these limited data indicate several areas for improvement in the provision of humanitarian aid to meet the needs and overcome the access barriers faced by elderly persons.

Although elders were limited in their ability to care for themselves and others by their underfunded and under-resourced environments – a sentiment echoed by Lebanese social workers – they highlight the importance of social and family ties during chaotic times, likening their role in the community to that of the social workers who help them. While social workers are more equipped to help with tangible things such as food, shelter, and UNHCR registration, elders play an equally important role in emotional support for their communities.

From a clinical perspective, it is clear that depression and its comorbid cognitive disorders impact a person’s well-being, family attachment, and social functioning (Adams & Moon, 2009). These disorders become increasingly alarming, however, in the case of elder refugees. While this needs assessment points to the presence of depression and cognitive deficits in this community, it is impossible to compare the significance of these data against other countries affected by displacement, as no other research has been conducted in similar contexts using these batteries. Still, these limited data underscore the lack of budgeting for mental health services by UNHCR and the Lebanese medical system (El Chammay, Kheir, & Alaouie, 2013; ‘Lebanon needs $2.6 billion’, 2013; ‘Reforming mental health’, n.d.). A notable contributing factor to refugees’ resilience is family connectedness, which both elders and fieldworkers in our research confirm is alarmingly fragile during times of war. Warmth in family connections, in conjunction with a regular schedule of school, work, housework, and storytelling, fosters a sense of normalcy that allows elders to heal (Ajdukovic, 2004; ‘Resilience in Palestinian adolescents’, 2017). This leads us to make important conclusions about how to remove obstacles to family connectedness and reinforce actions that support it.

This research builds from a multi-faceted concept of resilience, shedding some light on the role and wishes of elders to be positive forces in their communities, including those in refugee encampments. These elders are key to preserving the core values of Arab society in the Mediterranean – values like family connections, good food, and prayer. These values are vital to community support structures and should be strengthened in the hardship of displacement.

4. Conclusions

Despite the multiple limitations in our study, we believe that it could be used as a springboard to start a much-needed discussion on elders’ needs, especially during hardship. For that, we invite all actors in the field to be aware of elders’ unique needs, especially in refugee populations. For UNHCR, we recommend the use of a new registration system that is lenient to elders above 65 years old, who often face barriers in filling out and misplacing paperwork, or frankly forgetting to have their paperwork with them. For the Lebanese government, we recommend prioritising family reunification and facilitating visa procedures to keep families united, especially when elders are involved. In doing so, they can help preserve the wise and peaceful role of the elders as head of the family. For all humanitarian agencies on the ground, including UNHCR, MOSA, the Syrian Project Desk, and NGOs, we recommend taking the time to train fieldworkers in resilience and self-care so that they can better respond to the needs of elder refugees (Chemali et al., 2017). While improvements can be made to the distribution of food, toiletries, and medicine, resources must also surpass tangible needs to address the health and well-being of refugees, extending to include interventions that strengthen psychosocial support structures. In this vein, we urge actors such as the Lebanon Health Working Group’s Mental Health & Psychosocial Support Task Force (MHPSS TF) and the National Mental Health Programme to make use of our data in their work. By giving a voice to elders and empowering their positive social roles in refugee communities, we are making steps towards change and, ultimately, a lasting peace.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Ministry of Social Affairs Staff and the Syrian Project Desk; the Lebanese fieldworkers from all regions and especially fieldworkers from El-Marj and Rachaya, and Mr Hussein Salem, region director. Their wonderful and compassionate work on a daily basis to alleviate suffering and support communities through the horrible realities of war and trauma is outstanding. We would also like to thank the elder Syrian refugees who talked to us and shared with us their thoughts and daily lives. Without them, our work could not see the light.

Funding

This work was supported by Philanthropy-Peace in Medicine Sundry Fund [grant number 217556].

Appendix

Study forms

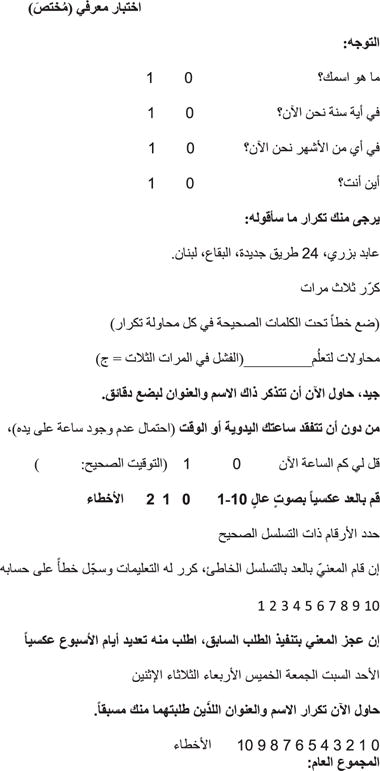

Semi-structured qualitative survey with Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) questions

MOSA fieldwork survey – Concentrating on elders

Demographic profile for elders in the encampment

Greatest concerns of elder refugees?

What are the current gaps in services provided?

- Is diet adequate? How often do they eat:

- Meat

- Fruit and vegetable

- Fish

- Sweets

- Luxury items

- Do they take any vitamins?

- GDS

- Do you frequently worry about the future?

- Do you feel that your situation is hopeless?

- Do you feel that your life is empty?

- Do you often get bored?

- Are you hopeful about the future?

- Are you afraid something bad is going to happen to you?

What social support is available?

How do refugee families shoulder the burden of elder care?

Who is family in Syria and who is family here?

In your mind, what is the role of fieldworkers (social workers) who help you out in your current situation?

In your situation today, could you think of one thing you are grateful for? One thing you would like to change?

MOSA fieldwork survey- Concentrating on elders

MOSA

MOSA

Brief Cognitive Impairment Scale (BCIS) (adapted)

Short (Adapted) Cognitive Test

| Orientation | ||

| What is your name | 0 | 1 |

| What year is it now? | 0 | 1 |

| What month? | 0 | 1 |

| Where are you? | 0 | 1 |

Please repeat after me

Abed Bizri, 24 Tarik Jdideh, Bekaa, Loubnan

Repeat 3 times

(Underline words repeated correctly in each trial)

Trials to learning: ________ (can’t do in 3 trials = C)

Good, now remember that name and address for a few minutes.

Without looking at your watch or clock (they may not have any),

Tell me about what time it is: 0 1 (correct time: ___________)

Count aloud backwards 10 to 1: 0 1 2 errors

Mark correctly sequenced numerals

If subject starts counting forward or forgets the task, repeat instructions and score 1 error

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

If cannot count, try days of the week backwards

Sun Sat Fri Thurs Wed Tues Mon

Repeat the name and address I asked you to remember.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 errors

Total score:

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abrams RC, Lachs M, McAvay G, Keohane DJ, Bruce ML. Predictors of self-neglect in community-dwelling elders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1724–1730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KB, Moon H. Subthreshold depression: Characteristics and risk factors among vulnerable elders. Aging and Mental Health. 2009;13(5):682–692. doi: 10.1080/13607860902774501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdukovic D. Social contexts of trauma and healing. Medicine, Conflict and Survival. 2004;20(2):120–135. doi: 10.1080/1362369042000234717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DN. Brief cognitive rating scale. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2011:446–447. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi L, Chemali Z. A conceptual framework of displaced elderly Syrian refugees in Lebanon: Challenges and opportunities. Global Journal of Health Science. 2016;8(11):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- The Benson Henry Institute 3RP SMART Program. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.bensonhenryinstitute.org/training-apply-for-certification/

- Chaaya M, Sibai A, Roueiheb ZE, Chemaitelly H, Chahine LM, Al-Amin H, Mahfoud Z. Validation of the Arabic version of the short geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) IPG International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;20(03) doi: 10.1017/s1041610208006741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemali Z, Borba CPC, Johnson KA, Hock RS, Parnarouskis L, Henderson DC, Fricchione GL. Humanitarian space and wellbeing: Effectiveness of training on a psychosocial intervention for host community-refugee interaction. Medicine, Conflict, and Survival. 2017 doi: 10.1080/13623699.2017.1323303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Chammay R, Kheir W, Alaouie H. Assessment of mental health and psychosocial support services for Syrian refugees in Lebanon. 2013 Retrieved from data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=4575.

- Forgotten Voices. An insight into older persons among refugees from Syria in Lebanon. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.alnap.org/resource/8693.

- Gillam S. Hidden victims: New research on older, disabled and injured Syrian refugees. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.helpage.org/newsroom/latest-news/hidden-victims-new-research-on-older-disabled-and-injured-syrian-refugees/

- Kariuki F. Conflict resolution by elders in Africa: Successes, challenges and opportunities. Kariuki Muigua & Co. Advocates; 2015. Retrieved from https://www.ciarb.org/docs/default-source/centenarydocs/speaker-assets/francis-kariuki.pdf?sfvrsn=0. [Google Scholar]

- Lebanon needs $2.6 billion to counter Syria war impact. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-meast-investment-lebanon-budget-idUSBRE99T0YJ20131030.

- M T. Amos: Syrian refugees make up 25 to 30 percent of Lebanon’s population. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.naharnet.com/stories/en/170438.

- Reforming mental health in Lebanon amid refugee crises. :564–565. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.030816. n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Resilience in Palestinian adolescents living in Gaza: Correction to Aitcheson et al. (2016) Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2017;9(1):125–125. doi: 10.1037/tra0000175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahrawi and Afghan Children and Adolescents. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://forcedmigration.org/research-resources/expert-guides/sahrawi-and-afghan-children-and-adolescents/alldocuments.

- Shayda N, Sayah H, Strong J, Varady JC. Forgotten voices. An insight into older persons among refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Caritas Lebanon Migrant Center. n.d. Retrieved from www.caritasmigrant.org.lb.

- Strong J, Varady C, Chahda N, Doocy S, Burnham G. Health status and health needs of older refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Conflict and Health Confl Health. 2015;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s13031-014-0029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syria Emergency. (n.d.) Retrieved from unhcr.org/en-us/syria-emergency.html.