Abstract

Objective

Little is known about Latino parents’ perceptions of weight-related language in English or Spanish, particularly for counseling obese youth. We sought to identify English and Spanish weight counseling terms perceived by Latino parents across demographic groups as desirable for providers to use, motivating, and inoffensive.

Methods

Latino parents of children treated at urban safety-net clinics completed surveys in English or Spanish. Parents rated the desirable, motivating, or offensive properties of terms for excess weight using a 5-point scale. We compared parental ratings of terms and investigated the association of parent and child characteristics with parent perceptions of terms.

Results

A total of 525 surveys met inclusion criteria (255 English, 270 Spanish). English survey respondents rated “unhealthy weight” and “too much weight for his/her health” the most motivating and among the most desirable and least offensive terms. Spanish survey respondents found “demasiado peso para su salud” highly desirable, highly motivating, and inoffensive, and respondents valued its connection to the child’s health. Commonly used clinical terms “overweight”/“sobrepeso” and “high BMI [body mass index]”/“índice de masa corporal alta” were not as desirable or as motivating. “Chubby,” “fat,” “gordo,” and “muy gordo” were the least motivating and most offensive terms. Parents’ ratings of commonly used clinical terms varied widely across demographic groups, but more desirable terms had less variability.

Conclusions

“Unhealthy weight,” “too much weight for his/her health,” and its Spanish equivalent, “demasiado peso para su salud,” were the most desirable and motivating, and the least offensive terms. Latino parents’ positive perceptions of these terms occurred across parent and child characteristics, supporting their use in weight counseling.

Keywords: Hispanic Americans, Latino/Latina, pediatric obesity, Spanish, terms, weight counseling

Pediatric Health Care providers are tasked with providing motivating, inoffensive, and linguistically and culturally appropriate pediatric weight counseling.1–6 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that primary care providers assess and treat childhood overweight/obesity by providing family counseling, in addition to assessing medical and behavioral risk factors and using a stepwise approach to treatment.7 Incorporating culturally tailored content and using language that parents identify as desirable, motivating, and inoffensive can improve child health outcomes8,9 and increase family engagement during weight counseling. However, educational, linguistic, and cultural barriers continue to impede the delivery of preventive counseling.10,11 English speakers are up to 1.6 times more likely to receive diet and physical activity counseling than Spanish speakers,12,13 and non-Latino children are 2 times more likely to receive obesity counseling than Latino children14 despite Latino youth being disproportionately affected by childhood obesity.15

Providers’ lack of self-efficacy in counseling, provider–parent language incongruence, and provider uncertainty in what weight counseling terms to use influence how providers discuss child weight status.16,17 Multiple studies highlight the importance of avoiding derogatory and colloquial terms during weight counseling, but there is no consensus on what terms to use.1,16,18–24 In a study by Puhl et al,1 parents rated the terms “weight,” “unhealthy weight,” and “weight problem” the most desirable and motivating terms for use in pediatric weight counseling. However, the study included only English-speaking parents with Internet access and did not distinguish Latino from non-Latino parents. We have previously reported that English-speaking Latino parents in focus groups found “unhealthy weight” and “weight problem” confusing, as these phrases potentially could refer to an underweight or overweight child.25 However, these parents did not identify alternative terms to use instead. Spanish-speaking Latino parents suggested that the phrase “demasiado peso para su salud” (too much weight for his/her health) was more motivating than the commonly used clinical term “sobrepeso” (overweight), as it communicated that the child’s health was at risk.25

The challenge of providing pediatric weight counseling is further complicated by evidence that parent demographics, child age, and child weight status influence how providers communicate weight counseling, how parents react to weight counseling discussions, and how parents perceive weight counseling terms.1,16,18,26,27

The primary aim of this survey study was to identify English and Spanish weight counseling terms that are viewed as desirable, motivating, and inoffensive by Latino parents. The secondary aim was to investigate the association of parent and child characteristics with parent perception of weight counseling terms. To maximize clinical utility of our results, we sought to identify terms that might elicit a consistently motivating and inoffensive response across the demographic groups studied. Finally, we used qualitative methods to evaluate written comments from survey respondents to better understand our primary aim.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

Denver Health (DH) is Colorado’s largest safety-net health care system.28 Ninety-eight percent of DH primary care patients report income below 200% of the federal poverty level. Of all DH pediatric patients aged 2 to 19 years, 19% are obese, compared to 16.9% nationally.15 Sixty-three percent (approximately 34,000) of DH pediatric patients or their parents identify as Hispanic or Latino; of those, 50% prefer the Spanish language. Of the Latino pediatric patients cared for by this health system, 38% are obese or overweight.

Survey Methods

Recruitment and Eligibility

Bilingual research assistants administered a survey in English or Spanish to a convenience sample of self-identified Latino parents of pediatric patients aged 2 to 18 years at 4 urban safety-net clinics. Research assistants approached parents in clinic waiting rooms to assess eligibility and interest in completing the survey before and after their scheduled clinic appointment. Parents were eligible for the survey if they were age 18 or older, self-identified as Latino or Hispanic, and provided informed consent. The research assistants were available to answer questions, assist participants with limited literacy, and supervise the collection of the surveys. Parents chose whether to take the survey in either English or Spanish. Participants received a $10 grocery store gift card.

The target sample size of 230 participants within each language group was estimated on the basis of demographic characteristics, explaining at least 20% of the variability in term preference with 85% power.

Survey Design

The survey was designed to complement the approach of Puhl et al,1 who assessed preference for terms to describe child weight status in an exclusively English-speaking population.3 Using exploratory sequential methodology,29 we used findings from our previously conducted focus groups with Latino parents to prioritize weight counseling terms and additional measures for inclusion in this survey.25 The survey was piloted with 30 parents who matched inclusion criteria and gave feedback on survey language and layout. This feedback was incorporated into the final version of the survey.

Key survey components are listed in Table 1. The survey presented a hypothetical scenario to parents, modified from previous studies.1,18 Parents were asked to then rate the desirable, motivating, and offensive qualities of weight counseling terms using 5-point Likert scales. English surveys included a list of 12 English terms, which included 10 terms previously studied by Puhl et al,1 plus 2 additional phrases based on our previous parent and health care provider focus groups.25 The Spanish surveys listed 11 terms identified in our previous parent and health care provider focus groups.25 Spanish terms that are direct translations of English terms (and vice versa) (ie, “obese” and “obeso”) were included in the surveys only if they were suggested during the prior focus groups.25 To assist in explaining results, an open-ended question embedded within the survey29 prompted parents to clarify why they ranked terms at either extreme of the desirability scale.

Table 1.

Survey Components

| Scenario*: “Imagine you have brought your child into the doctor for a routine checkup. The nurse has measured your child. He/she weighs much more than recommended for a child of his/her age. Your doctor will be in shortly to talk with you and your child. You like your doctor and believe he/she cares about your child’s health. Because doctors can use different words to talk about weight, please tell us, “If your child weighed more than recommended…” | |

| Term desirability | “How much would you like or not like the doctor to use the following words to describe your child’s weight?” Scale: 1 = Not at all, 2 = Not very much, 3 = Undecided, 4 = A little, 5 = Very much Open-ended question: “For any word you marked that you would like it ‘not at all’ or ‘very much,’ please write in why you would really like or not like that word or phrase.” |

| Term motivation | “How much would each of these words or phrases make you want to help your child lose weight?” Scale: 1 = Not at all, 2 = Not very much, 3 = Undecided, 4 = A little, 5 = Very much |

| Term offensiveness | “How likely do you think each of these words or phrases would make your child feel badly about themselves?” Scale: 1 = Definitely no, 2 = Probably no, 3 = Undecided, 4 = Probably yes, 5 = Definitely yes |

| English Survey Terms | Spanish Survey Terms |

|---|---|

| Weight† | Peso‡ |

| Too much weight for his/her health‡ | Demasiado peso para su salud‡ |

| Too much weight for his/her age‡ | Demasiado peso para su edad‡ |

| High BMI† | Indice de masa corporal alta‡ |

| Overweight† | Sobrepeso‡ |

| Obese† | Obeso‡ |

| Fat† | Gordo‡ |

| Chubby† | Gordito‡ |

| Heavy†,§ | |

| Weight problem†,§ | |

| Unhealthy weight†,§ | |

| Extremely obese†,§ | |

| Engordando‡,‖ (Getting fatter) | |

| Muy gordito‡,‖ (Very chubby) | |

| Muy gordo‡,‖ (Very fat) |

Additional survey components included the following: 1) demographic questions about the parent (survey respondent) and the child presenting for care on the day of the survey (if the parent indicated that the clinic visit was for more than 1 child, characteristics for child listed first on the survey were used), 2) a validated (in English and Spanish) 1-item screen for health literacy,30–32 3) 5 language-use questions from the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH),33,34 and 4) questions to query past experiences with weight-related bullying for the parent and child.32,34 Parents also reported their own weight and height, from which parental body mass index (BMI) and weight status were later calculated. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institution Review Board.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics of participants who took the survey in English or Spanish. For our primary aim, parent ratings of the desirable, motivating, and offensive qualities of the terms (12 English terms, 11 Spanish terms) were evaluated by language group with means and 95% confidence intervals.

For our secondary aim, we selected 4 terms from each language (Fig. 1) to examine in our regression models on the basis of the following criteria: 1) terms that had been rated highly desirable, motivating, and preferred in this study or prior studies,1,18,25 and 2) terms used commonly in clinic visits, based on our health care personnel focus groups25 and on our clinical experience. First, we conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses to estimate the unadjusted associations between parent and child characteristics with the outcome of parental ratings of these weight counseling terms. As described in Figure 1, parent and child characteristics were included in the models if previous studies showed the characteristic had significant effect on term perception,1,18 or if previous studies showed no significant effect on term perception1,18 but we perceived strong rationale to retest in a low-income Latino population (eg, parent educational achievement), or the characteristic had not been previously examined and there was strong interest among the authors in exploring its effects among this low-income Latino population (eg, country of birth and confidence filling out medical forms). As a result of the limited variability of acculturation scores within language groups, acculturation was not examined in these models. For each of the included parent and child characteristics, 24 bivariate models were run, representing a model for each of the desirable, motivating, and offensive qualities of 4 English and 4 Spanish terms. Then we conducted multivariable logistic regression models to examine the independent association between each parent and child characteristic and term preference while adjusting for all other listed parent and child characteristics.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model and rationale for components of regression analysis.

On the basis of the response distributions of parent ratings for all the terms, we defined a response of 4 or 5 as strong parental perception of the desirable, motivating, or offensive quality of term. In both the unadjusted and multivariable models, the outcome was dichotomized as choosing 4 or 5 (vs 1, 2, or 3) on the 1 to 5 scale. We used the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests to assess adequate fit of each model to the data.35,36 For multivariable models, we calculated each model’s R2 value to describe the degree of variance accounted for by the parent and child characteristics we measured. We also assessed multicollinearity of parent and child characteristics in the multivariable models and determined a priori that any variables with a tolerance below 0.40 would indicate further assessment for possible removal from the model.37

All quantitative analyses were conducted by SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

To further understand parents’ perception of terms as desirable, parents’ responses to the open-ended question were entered into an Access (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) database for qualitative analysis. A bilingual study team member and certified interpreter (SR) then translated Spanish-language responses while preserving the original syntax. The responses were reviewed by the qualitative expert (AKR) to create the initial codebook with detailed definitions; this codebook was then presented to the team for comments and revisions. Using Atlas.ti software, all parent responses were coded and discussed until 2-coder (SK, AC) consensus was reached. Additional codes were created ad hoc during the analysis as needed. The qualitative team (AKR, SK, AC) then conducted a focused analysis of codes. Results were summarized first by term and then categorized by interpretation of parent response.

Results

Of 534 surveys administered, 529 (99%) were completed and 525 (98%) met the inclusion criteria (255, 49%, English; 270, 51%, Spanish) (Table 2). Over 80% of respondents reported Medicaid coverage for their child. More English survey respondents reported attending some college or higher. Over 80% of respondents reported an annual household income of $30,000 or less. Among Spanish survey respondents, 87% reported being born in Mexico, and 96% had a low degree of acculturation as measured by the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics.33,34 Ten percent of all respondents reported low confidence in filling out medical forms, suggesting low health literacy.30–32 Forty percent of responding parents were obese, consistent with national obesity prevalence for Hispanic or Latino adults.15

Table 2.

Description of Survey Participants (Parents) by Language

| Characteristic | English (n = 255) |

Spanish (n = 270) |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Characteristics | ||

| Parent age, y | (n = 244) | (n = 223) |

| Mean (SD) | 32.02 (8.83) | 34.6 (7.17) |

| Median (5th, 95th percentiles) | 30.5 (21,50) | 34 (24, 46) |

| Parent gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 231 (90.6) | 237 (87.8) |

| Male | 21 (8.2) | 30 (11.1) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| Parent education level, n (%) | ||

| Less than 9th grade (no high school) | 49 (19.2) | 131 (48.5) |

| Some high school (did not graduate) | 62 (24.3) | 51 (18.9) |

| Graduated from high school or completed GED | 68 (26.7) | 51 (18.9) |

| Some higher education (college, technical school, or higher) | 72 (28.2) | 28 (10.4) |

| Not reported | 4 (1.6) | 9 (3.3) |

| Household income, n (%) | ||

| Less than $10,000 per year | 135 (52.9) | 105 (38.9) |

| $10,001–$30,000 per year | 71 (27.8) | 118 (43.7) |

| $30,001–$70,000 per year | 25 (9.8) | 23 (8.5) |

| Not reported | 24 (9.4) | 24 (8.9) |

| Parent country of birth, n (%) | ||

| United States | 216 (84.7) | 23 (8.5) |

| Mexico | 38 (14.9) | 235 (87.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 10 (3.7) |

| Not reported | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Parent acculturation score, n (%) | ||

| Less acculturated (<3) | 38 (14.9) | 259 (95.9) |

| More acculturated (≥3) | 216 (84.7) | 7 (2.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.5) |

| Parent confidence filling out medical forms,* n (%) | ||

| Confident | 228 (89.4) | 246 (91.1) |

| Not confident | 26 (10.2) | 24 (8.9) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Parent weight status,† n (%) | ||

| Underweight | 3 (1.2) | 6 (2.2) |

| Normal | 65 (25.5) | 53 (19.6) |

| Overweight | 58 (22.7) | 77 (28.5) |

| Obese | 121 (47.5) | 109 (40.4) |

| Not reported | 8 (3.1) | 25 (9.3) |

| Parent history of history of weight-based teasing or discrimination, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 70 (27.45) | 58 (21.48) |

| No | 173 (67.84) | 203 (75.19) |

| Not reported | 12 (4.71) | 9 (3.33) |

| Child Characteristics‡ | ||

| Child’s age, y | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.49 (4.44) | 7.97 (4.33) |

| Median (5th, 95th percentiles) | 6 (2, 16) | 7 (2, 16) |

| Child gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 133 (52.2) | 124 (45.9) |

| Male | 115 (45.1) | 140 (51.9) |

| Not reported | 7 (2.8) | 6 (2.2) |

| Health insurance of child/children, n (%) | ||

| Medicaid | 221 (86.7) | 226 (83.7) |

| CHIP | 23 (9.0) | 26 (9.6) |

| Other | 9 (3.5) | 15 (5.6) |

| Missing | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) |

| Child overweight or obese,§ n (%) | ||

| Yes | 94 (36.9) | 95 (35.2) |

| No | 147 (57.6) | 160 (59.3) |

| Not reported | 14 (5.5) | 15 (5.6) |

| Child history of teasing, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 50 (19.61) | 41 (15.19) |

| No | 192 (75.29) | 217 (80.37) |

| Not reported | 13 (5.10) | 12 (4.44) |

SD indicates standard deviation; GED, General Educational Development; BMI, body mass index; and CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program.

“How confident are you filling out forms by yourself?” Confident = 1 (Extremely confident), 2 (Quite a bit confident), and 3 (Somewhat confident). Not confident = 4 (A little bit confident), and 5 (Not at all confident). If the parent answered 1, 2, or 3, he or she was categorized as confident; if the parent answered 4 or 5, he or she was categorized as not confident.

Parent weight status was determined from parent BMI calculated on the basis of self-reported weight and height.

If the parent indicated that the clinic visit was for more than 1 child, child characteristics for the first child were used.

Child overweight or obese status was based on BMI calculated from medical assistant–recorded height and weight values on day of survey.

Overall Mean Term Ratings

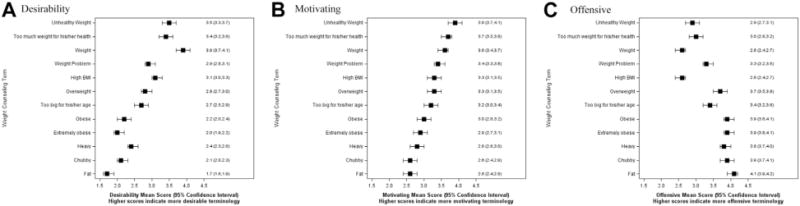

The mean desirable, motivating, and offensive ratings of the English and Spanish terms are presented in Figures 2 and 3. The most motivating English terms were “unhealthy weight” and “too much weight for his/her health.” The most motivating Spanish terms were “demasiado peso para su salud” and “demasiado peso para su edad.” Each of these 4 most motivating terms was also among the most desirable and least offensive. While the general terms of “weight” and its Spanish equivalent, “peso,” were rated the most desirable and least offensive, they were not rated as highly on motivating properties. The commonly used clinical terms “high BMI”/“índice de masa corporal alta” and “overweight”/“sobrepeso” were not rated to be as desirable or motivating. “Chubby,” “fat,” “gordo,” and “muy gordo” were the least desirable, least motivating, and most offensive terms.

Figure 2.

Parental perceptions (mean ratings) of weight counseling terms in English. (A) Desirability: “How much would you like or not like the doctor to use the following words to describe your child’s weight?” (B) Motivating: “How much would each of these words or phrases make you want to help your child lose weight?” (C) Offensive: “How likely do you think each of these words or phrases would make your child feel badly about themselves?”

Figure 3.

Parental perceptions (mean ratings) of weight counseling terms in Spanish. (A) Desirability: “How much would you like or not like the doctor to use the following words to describe your child’s weight?” (B) Motivating: “How much would each of these words or phrases make you want to help your child lose weight?” (C) Offensive: “How likely do you think each of these words or phrases would make your child feel badly about themselves?”

Logistic Regression

Because we reasoned that providers would find it useful to know if using a term for high weight status would elicit variable responses from parents of differing demographics, we explored associations of parent and child characteristics with perceptions of terms in bivariate and multivariable logistic regression. Bivariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated significant associations of multiple parent and child characteristics with parental perceptions of the weight terms (Tables 3 and 4). We assessed for inflation of variance due to possible multicollinearity. None of the models contained a variable with a tolerance of <0.40, so we did not remove any variables due to collinearity. For all but one model, the Hosmer-Lemeshow tests indicated adequate model fit. The model for desirability ratings of the term “high BMI” did not have adequate fit (P = .024), and those adjusted results are not reported. For the 30 multivariable logistic models adjusting for all listed parent/child characteristics, R2 ranged from 0.0649 to 0.3650.

Table 3.

Parental Rating of English Terms as Desirable, Motivating, and Offensive†

| Too Much Weight for His/Her Health

|

Unhealthy Weight

|

High BMI

|

Overweight

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

||

| Characteristic | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR‡ | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | |

| Parent Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Parent age, y | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) |

1.00 (0.96–1.05) |

1.01 (0.97–1.04) |

0.98 (0.94–1.01) |

0.98 (0.94–1.03) |

1.00 (0.97–1.04) |

‡ | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) |

1.01 (0.96–1.06) |

0.99 (0.95–1.03) |

1.00 (0.96–1.04) |

0.96 (0.92–1.00) |

|

| Parent gender (female vs male) | 1.04 (0.32–3.41) |

0.59 (0.16–2.13) |

1.45 (0.45–4.67) |

0.52 (0.16–1.73) |

1.11 (0.30–4.14) |

1.98 (0.61–6.43) |

‡ | 1.24 (0.40–3.89) |

5.15 (0.59–44.91) |

1.51 (0.45–5.12) |

0.89 (0.28–2.84) |

1.06 (0.26–4.24) |

|

| Parent education (reference: less than 9th grade [no high school]) | |||||||||||||

| Some high school (did not graduate) | 0.68 (0.24–1.94) |

1.19 (0.41–3.43) |

0.86 (0.32–2.31) |

0.63 (0.23–1.69) |

0.61 (0.20–1.87) |

0.60 (0.23–1.59) |

‡ | 1.64 (0.58–4.59) |

0.74 (0.20–2.75) |

1.42 (0.49–4.10) |

2.63 (0.96–7.25) |

0.66 (0.18–2.40) |

|

| Graduated from high school or completed GED | 0.89 (0.31–2.60) |

1.70 (0.57–5.10) |

1.27 (0.47–3.43) |

0.87 (0.31–2.44) |

1.23 (0.36–4.18) |

0.42 (0.16–1.16) |

‡ | 2.42 (0.85–6.91) |

0.9 (0.25–3.21) |

5.09 (1.71–15.15)* |

6.24 (2.11–18.40)* |

0.41 (0.12–1.47) |

|

| Some higher education (college, technical school, or higher) | 0.58 (0.20–1.67) |

1.79 (0.62–5.16) |

0.82 (0.30–2.24) |

0.61 (0.23–1.67) |

0.94 (0.20–2.97) |

0.35 (0.13–0.96)* |

‡ | 2.32 (0.84–6.45) |

0.58 (0.15–2.22) |

1.75 (0.60–5.09) |

4.30 (1.52–12.15)* |

0.24 (0.07–0.82)* |

|

| Household income (reference: less than $10,000 per year) | |||||||||||||

| Between $10,001 and $30,000 per year | 0.73 (0.34–1.56) |

0.64 (0.29–1.41) |

0.97 (0.47–1.99) |

0.84 (0.41–1.75) |

0.70 (0.31–1.62) |

0.72 (0.34–1.50) |

‡ | 0.86 (0.41–1.78) |

1.44 (0.56–3.71) |

1.89 (0.90–3.97) |

1.25 (0.59–2.66) |

0.81 (0.35–1.86) |

|

| Between $30,001 and $70,000 per year | 0.80 (0.25–2.59) |

0.32 (0.10–1.09) |

0.84 (0.27–2.62) |

0.69 (0.22–2.21) |

2.32 (0.42–12.65) |

0.93 (0.30–2.93) |

‡ | 1.09 (0.35–3.44) |

2.20 (0.54–9.04) |

1.34 (0.42–4.29) |

0.42 (0.13–1.33) |

1.6 (0.41–6.16) |

|

| Parent US born? (yes vs no) | 0.39 (0.13–1.18) |

0.85 (0.32–2.29) |

1.06 (0.42–2.66) |

1.10 (0.44–2.76) |

0.6 (0.20–1.84) |

1.70 (0.66–4.37) |

‡ | 0.45 (0.17–1.18) |

0.67 (0.22–2.09) |

0.33 (0.13–0.87)* |

0.43 (0.16–1.19) |

6.63 (2.39–18.38)* |

|

| Parent confidence filling out medical forms§: confident vs reference: not confident | 0.30 (0.08–1.17) |

1.28 (0.41–3.94) |

2.93 (0.83–10.30) |

1.16 (0.39–3.47) |

2.29 (0.72–7.23) |

1.93 (0.64–5.83) |

‡ | 0.86 (0.28–2.60) |

1.26 (0.28–5.62) |

0.79 (0.24–2.57) |

1.93 (0.61–6.10) |

0.42 (0.09–1.87) |

|

| Parent overweight or obese? (yes vs no)‖ | 0.91 (0.43–1.91) |

0.67 (0.30–1.45) |

1.10 (0.54–2.23) |

0.86 (0.42–1.76) |

0.86 (0.37–1.96) |

1.50 (0.73–3.09) |

‡ | 0.78 (0.38–1.59) |

1.07 (0.42–2.70) |

1.39 (0.66–2.93) |

1.32 (0.66–2.65) |

1.12 (0.49–2.53) |

|

| Parent with history of weight-based teasing or discrimination? (yes vs no) | 0.52 (0.23–1.19) |

1.27 (0.52–3.07) |

2.13 (0.95–4.74) |

2.9 (1.17–7.21)* |

1.84 (0.68–5.02) |

1.66 (0.73–3.09) |

‡ | 0.94 (0.42–2.11) |

0.68 (0.22–2.08) |

0.93 (0.41–2.12) |

1.4 (0.60–3.23) |

1.17 (0.46–2.98) |

|

| Child Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Child age, y | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) |

1.01 (0.92–1.10) |

0.99 (0.91–1.08) |

1.04 (0.96–1.13) |

1.01 (0.92–1.11) |

1.02 (0.94–1.11) |

‡ | 1.00 (0.92–1.00) |

0.98 (0.88–1.09) |

1.07 (0.98–1.16) |

1.02 (0.94–1.11) |

1.03 (0.94–1.12) |

|

| Child gender (female vs male) | 0.70 (0.37–1.34) |

0.48 (0.24–0.96)* |

1.12 (0.60–2.08) |

1.23 (0.65–2.31) |

0.55 (0.26–1.18) |

0.83 (0.45–1.55) |

‡ | 0.95 (0.51–1.78) |

0.57 (0.25–1.31) |

0.95 (0.50–1.82) |

1.32 (0.69–2.51) |

0.56 (0.27–1.17) |

|

| Child insured through Medicaid? (yes vs no) | 0.65 (0.22–1.96) |

0.45 (0.13–1.53) |

0.95 (0.34–2.64) |

0.48 (0.15–1.53) |

0.56 (0.13–2.44) |

0.62 (0.22–1.78) |

‡ | 0.34 (0.11–1.02) |

0.35 (0.11–1.13) |

1.27 (0.43–3.72) |

0.42 (0.13–1.35) |

2.35 (0.76–7.31) |

|

| Child overweight or obese? (yes vs no)¶ | 0.93 (0.47–1.86) |

1.11 (0.54–2.29) |

1.13 (0.58–2.20) |

1.06 (0.54–2.09) |

1.02 (0.46–2.25) |

0.96 (0.50–1.85) |

‡ | 1.49 (0.76–2.93) |

0.49 (0.19–1.22) |

1.01 (0.50–2.02) |

1.32 (0.66–2.65) |

0.95 (0.44–2.06) |

|

| Child with history of weight-based teasing or discrimination? (yes vs no) | 1.20 (0.49–2.93) |

0.58 (0.23–1.48) |

0.80 (0.33–1.93) |

0.25 (0.10–0.64)* |

0.64 (0.23–1.78) |

1.12 (0.47–2.65) |

‡ | 0.86 (0.35–2.15) |

1.78 (0.54–5.87) |

0.75 (0.30–1.88) |

0.45 (0.18–1.13) |

0.58 (0.22–1.53) |

|

aOR indicates adjusted odds ratio; GED, General Educational Development; and BMI, body mass index.

Ninety-five percent confidence intervals presented below each aOR.

Statistically significant.

aORs adjust for all other listed parent and child characteristics. Outcome for aORs was 4 or 5 on 5-point scale. For the Desirability and Motivating questions, outcome was 4 = A little or 5 = Very much. For the Offensive questions, outcome was 4 = Probably yes or 5 = Definitely yes. Sample sizes for individual analyses range from 183 to 191 for adjusted models. Survey responses with missing information on any of the parent/child characteristics were excluded from the models.

Hosmer-Lemeshow tests indicated that the model for desirability ratings of the term “High BMI” did not have adequate fit (P = .024), and those adjusted results are not reported.

“How confident are you filling out forms by yourself?” Confident = 1 (Extremely confident), 2 (Quite a bit confident), and 3 (Somewhat confident). Not confident = 4 (A little bit confident), and 5 (Not at all confident). If the parent answered 1, 2, or 3, he or she was categorized as confident; if the parent answered 4 or 5, he or she was categorized as not confident.

Parent weight status was determined from parent BMI calculated on the basis of self-reported weight and height.

Child overweight or obese status was based on BMI calculated from medical assistant–recorded height and weight values on day of survey.

Table 4.

Parental Rating of Spanish Terms as Desirable, Motivating, and Offensive†

| Demasiado Peso Para Su Salud

|

Demasiado Peso Para Su Edad

|

Indice de Masa Corporal Alta

|

Sobrepeso

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

Desirable

|

Motivating

|

Offensive

|

||

| Characteristic | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | |

| Parent Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Parent age, y | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) |

0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

1.00 (0.94–1.05) |

0.99 (0.94–1.05) |

1.01 (0.96–1.06) |

0.94 (0.89–1.00)* |

0.92 (0.87–0.98)* |

0.98 (0.93–1.04) |

0.98 (0.94–1.04) |

0.97 (0.92–1.02) |

0.99 (0.94–1.04) |

|

| Parent gender (female vs male) | 2.61 (0.87–7.84) |

4.62 (1.47–14.60)* |

3.35 (0.85–13.14) |

2.65 (0.87–8.04) |

2.78 (0.83–9.30) |

2.54 (0.72–8.93) |

6.10 (1.45–24.95)* |

12.22 (2.78–53.81)* |

1.02 (0.33–3.18) |

2.71 (0.79–9.37) |

2.56 (0.75–8.75) |

2.41 (0.79–7.35) |

|

| Parent education (reference: less than 9th grade [no high school]) | |||||||||||||

| Some high school (did not graduate) | 1.37 (0.56–3.35) |

1.41 (0.54–3.66) |

0.30 (0.12–0.78)* |

1.26 (0.52–3.04) |

1.92 (0.72–5.15) |

0.67 (0.28–1.62) |

2.44 (0.99–5.98) |

3.79 (1.42–10.11)* |

0.52 (0.20–1.30) |

1.25 (0.53–2.92) |

1.39 (0.58–3.32) |

0.8 (0.35–1.86) |

|

| Graduated from high school or completed GED | 2.29 (0.92–5.74) |

1.66 (0.93–7.59) |

0.64 (0.28–1.44) |

1.63 (0.69–3.86) |

2.54 (0.95–6.81) |

1.19 (0.53–2.67) |

3.18 (1.32–7.63)* |

1.73 (0.73–4.07) |

0.66 (0.28–1.56) |

1.39 (0.62–3.14) |

1.49 (0.65–3.43) |

0.73 (0.33–1.64) |

|

| Some higher education (college, technical school or higher) | 2.21 (0.70–6.96) |

3.37 (0.87–13.07) |

0.57 (0.20–1.62) |

3.47 (1.04–11.57)* |

5.10 (1.05–24.88)* |

0.94 (0.34–2.63) |

19.97 (4.56–87.47)* |

16.55 (3.48–78.73)* |

1.21 (0.44–3.34) |

11.30 (2.78–45.83)* |

6.94 (1.76–27.30)* |

0.8 (0.29–2.22) |

|

| Household income (reference: less than $10,000 per year) | |||||||||||||

| Between $10,001 and $30,000 per year | 0.83 (0.40–1.71) |

1.14 (0.53–2.47) |

1.27 (0.64–2.54) |

0.79 (0.39–1.60) |

1.36 (0.63–2.92) |

0.74 (0.38–1.47) |

0.77 (0.37–1.62) |

1.08 (0.52–2.26) |

1.31 (0.64–2.68) |

0.78 (0.39–1.54) |

1.09 (0.55–2.16) |

1.34 (0.69–2.59) |

|

| Between $30,001 and $70,000 per year | 0.57 (0.17–1.90) |

0.78 (0.18–3.42) |

1.8 (0.49–6.64) |

0.53 (0.16–1.75) |

1.44 (0.33–6.25) |

1.28 (0.37–4.46) |

0.88 (0.23–3.35) |

3.26 (0.58–18.16) |

1.58 (0.44–5.68) |

1.28 (0.36–4.54) |

3.69 (0.83–16.31) |

1.29 (0.40–4.18) |

|

| Parent US born? (yes vs no) | 0.26 (0.07–0.90)* |

0.49 (0.13–1.79) |

0.92 (0.23–3.71) |

0.26 (0.08–0.90)* |

0.33 (0.09–1.23) |

0.9 (0.23–3.49) |

0.58 (0.15–2.26) |

0.46 (0.11–1.91) |

1.02 (0.25–4.07) |

0.26 (0.06–1.12) |

0.46 (0.12–1.73) |

1.09 (0.31–3.85) |

|

| Parent confidence filling out medical forms‡: confident vs reference: not confident | 2.71 (0.75–9.75) |

3.6 (0.95–13.63) |

13.89 (1.61–119.93)* |

1.17 (0.34–4.08) |

3.81 (0.99–14.58) |

11.9 (1.40–101.53)* |

4.98 (0.88–28.14) |

10.68 (1.50–75.84)* |

10.13 (1.21–85.14)* |

1.46 (0.39–5.46)* |

0.93 (0.25–3.50) |

1.04 (0.30–3.60) |

|

| Parent overweight or obese? (yes vs no)d§ | 1.03 (0.46–2.31) |

0.44 (0.16–1.18) |

0.8 (0.37–1.73) |

1.59 (0.72–3.51) |

1.15 (0.48–2.75) |

0.91 (0.43–1.93) |

1.73 (0.75–4.03) |

0.82 (0.34–1.95) |

1.26 (0.57–2.78) |

0.6 (0.28–1.31) |

1.04 (0.47–2.32) |

0.96 (0.45–2.03) |

|

| Parent with history of weight-based teasing or discrimination? (yes vs no) | 0.94 (0.41–2.13) |

0.87 (0.37–2.08) |

1.00 (0.46–2.15) |

0.92 (0.42–2.01) |

1.76 (0.68–4.57) |

0.85 (0.39–1.82) |

1.14 (0.48–2.67) |

0.6 (0.25–1.42) |

0.83 (0.37–1.87) |

0.96 (0.44–2.08) |

2.43 (1.06–5.54)* |

1.42 (0.67–2.99) |

|

| Child Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Child age, y | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) |

0.99 (0.90–1.09) |

0.99 (0.90–1.07) |

0.98 (0.90–1.06) |

1.01 (0.92–1.10) |

0.94 (0.96–1.06) |

1.01 (0.92–1.10) |

1.13 (1.02–1.24)* |

0.94 (0.86–1.02) |

0.98 (0.90–1.07) |

1.05 (0.97–1.15) |

0.98 (0.90–1.06) |

|

| Child gender (female vs male) | 1.06 (0.54–2.06) |

1.26 (0.61–2.57) |

1.04 (0.54–2.01) |

1.19 (0.61–2.30) |

1.11 (0.54–2.29) |

1.33 (0.70–2.52) |

0.66 (0.33–1.35) |

1.2 (0.59–2.46) |

1.14 (0.59–2.21) |

1.29 (0.68–2.44) |

0.94 (0.49–1.81) |

1.66 (0.90–3.07) |

|

| Child insured through Medicaid? (yes vs no) | 2.02 (0.77–5.26) |

0.96 (0.32–2.91) |

1.81 (0.63–5.22) |

1.62 (0.62–4.20) |

0.85 (0.27–2.71) |

0.62 (0.24–1.61) |

0.55 (0.18–1.63) |

0.97 (0.31–3.04) |

0.81 (0.31–2.15) |

1.04 (0.39–2.78) |

1.84 (0.67–5.02) |

0.53 (0.21–1.38) |

|

| Child overweight or obese? (yes vs no)‖ | 1.04 (0.52–2.07) |

0.99 (0.48–2.07) |

0.99 (0.51–1.92) |

1.41 (0.71–2.79) |

1.05 (0.49–2.24) |

1.1 (0.57–2.10) |

0.79 (0.39–1.63) |

0.40 (0.19–0.84)* |

0.85 (0.43–1.68) |

0.99 (0.51–1.91) |

1.05 (0.54–2.06) |

0.97 (0.51–1.82) |

|

| Child with history of weight-based teasing or discrimination? (yes vs no) | 1.37 (0.50–3.66) |

0.92 (0.34–2.46) |

1.25 (0.50–3.13) |

0.8 (0.32–1.97) |

1.1 (0.38–3.22) |

1.49 (0.60–3.69) |

3.03 (1.07–8.57)* |

1.00 (0.36–2.75) |

1.35 (0.52–3.52) |

1.4 (0.57–3.44) |

0.58 (0.23–1.47) |

1.08 (0.45–2.57) |

|

aOR indicates adjusted odds ratio; GED, General Educational Development; and BMI, body mass index.

Ninety-five percent confidence intervals presented below each aOR.

Statistically significant.

aORs adjust for all other listed parent and child characteristics. Outcome for aORs was 4 or 5 on 5-point scale. For the Desirability and Motivating questions, outcome was 4 = A little or 5 = Very much. For the Offensive questions, outcome was 4 = Probably yes or 5 = Definitely yes. Sample sizes for individual analyses range from 183 to 191 for adjusted models. Survey responses with missing information on any of the parent/child characteristics were excluded from the models.

“How confident are you filling out forms by yourself?” Confident = 1 (Extremely confident), 2 (Quite a bit confident), and 3 (Somewhat confident). Not confident = 4 (A little bit confident), and 5 (Not at all confident). If the parent answered 1, 2, or 3, he or she was categorized as confident; if the parent answered 4 or 5, he or she was categorized as not confident.

Parent weight status was determined from parent BMI calculated on the basis of self-reported weight and height.

Child overweight or obese status was based on BMI calculated from medical assistant–recorded height and weight values on day of survey.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Results—English Terms

Of all the tested English and Spanish terms, parental ratings of “too much weight for his/her health” varied the least by parent or child demographics in adjusted models. The sole significant difference in ratings was that parents of girls responding to the English survey had lower odds of finding “too much weight for his/her health” motivating compared to parents with a boy. The term “unhealthy weight” had lower odds of offending the most educated parents, higher odds of being rated as desirable by parents who had experienced weight-based teasing or discrimination, but lower odds being rated desirable by parents of children who had been teased about their weight. We found no effects of the parent and child characteristics on parent rating of the motivating or offensive properties of “high BMI,” and the model for desirability of this term did not have adequate fit (data not shown). The term “overweight” had higher odds of being desired by parents who were high school graduates, higher odds of motivating parents who were high school graduates and those who completed some college, and lower odds of offending parents who completed some college, but less desirable and more offensive among English respondents born in the United States.

There was no demonstrated effect in any adjusted model of the following variables on any parental ratings of English terms: parent age, parent gender, household income, parent confidence in filling out forms, parent weight status, child age, child Medicaid coverage, and child weight status. Conversely, parent education and birth in the United States affected multiple ratings.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Results—Spanish Terms

For “demasiado peso para su salud,” respondents born outside the United States (91% of respondents) had higher odds of finding it desirable, and female caregivers had higher odds of finding it motivating. Parents with some high school education had lower odds of finding the phrase offensive, while parents who were confident in completing medical forms, a brief marker of health literacy, had much higher odds of finding the phrase offensive. For the phrase “demasiado peso para su edad,” respondents born outside the United States and those with education beyond high school had higher odds of finding the phrase desirable. Parents who reported being confident filling out medical forms had much higher odds of finding “demasiado peso para su edad” offensive.

Of all the terms tested, the parent ratings of the desirable, motivating, and offensive qualities of “índice de masa corporal alta” varied by the largest number of parent and child characteristics. This Spanish phrase for high BMI had higher odds of being viewed as desirable and motivating among younger, female, and more educated parents. It had higher odds of being both motivating and offensive to those with confidence completing medical forms. Child characteristics also influenced parents’ ratings of this term; “índice de masa corporal alta” had higher odds of being desired by parents of children who had experienced weight-related teasing, lower odds of motivating parents of overweight/obese children, but higher odds of motivating parents of older children.

The term “sobrepeso” had higher odds of being desirable and motivating to parents with more than high school education, and of being seen as motivating by parents who had a personal history with weight-based discrimination.

There was no demonstrated effect in adjusted models of the following variables on any parental ratings of Spanish terms: household income, parent weight status, child gender, and child Medicaid coverage. However, parent age, gender, education, birth in the United States, and confidence filling out medical forms significantly affected the perception of multiple Spanish terms.

Explanatory Analysis of Open-Ended Survey Question

Of all English and Spanish survey respondents, 163 (64%) English survey respondents and 213 (79%) Spanish survey respondents wrote in responses to the open-ended question asking for explanations for term desirability ratings of 1 = Not at all and 5 = Very much. The response rate to this question was 70% among English respondents and 81% among Spanish respondents who rated desirability of a term 1 or 5. Fifty-two percent of English respondents and 80% of Spanish respondents who appropriately provided a qualitative response reported feeling “extremely confident” or “quite a bit confident” in completing medical forms. Overall, 17 responses (7 English, 10 Spanish) were excluded after 2 reviewers (SK and AC) established that the meaning of the response could not be discerned.

Analysis of parents’ explanations for their desirability ratings yielded 3 key interpretations to explain parental ratings of terms across both Spanish and English survey respondent cohorts: 1) terms linking weight status to health (“too much weight for his/her health,” “unhealthy weight,” “demasiado peso para su salud”) are likely to be motivating and easily understood; 2) although “weight” and its Spanish equivalent, “peso,” are inoffensive, they may not be meaningful when used alone without further context; and 3) despite their common use in clinical settings, “overweight”/“sobrepeso” and “obese”/“obeso” may be offensive to Latino parents and their children. These interpretations, with illustrative quotes, are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Findings Based on Parents’ Free Text Explanations of Term Preferences

| Finding | English | Spanish |

|---|---|---|

| Finding 1. Terms linking weight status to health are both motivating and easily understood. | Too much weight for his/her health 1. “Having the word healthy makes it more appropriate and educational giving a chance for parents to explain to kids to eat more healthy.” Unhealthy weight 2. “Letting the child know there are concerns without hurting their feelings.” 3. “Teens can accept it better and understand it.” |

Demasiado peso para su salud 12. “Me gusta porque cuando hablen de salud uno pone más atención.” (I like it because when talking about health people pay more attention). 13. “Me gusta porque se explica más y suena menos ofensivo.” (I like it because it is self-explanatory and sounds less offensive). |

| Finding 2. While “weight” and its Spanish equivalent, “peso,” are nonblaming, neither may be effective in isolation. | Weight 4. “‘Weight’ is just a general word.” 5. “‘Weight’ is a general term.” |

Peso 14. “No se usa o no se entiende.” (Do not use [the term peso] or is not understandable). 15. “Se escucha mejor que le digan que está aumentando de peso, y que le expliquen sobre el peso.” (It would sound better if they said that he/she is gaining weight and they explain about the weight). |

| Finding 3. Despite common use in clinical settings, “overweight”/“sobrepeso” and “obese”/“obeso” may be poorly received by Latino parents. | Overweight 6. “Insulting and can put a complex on the kid.” 7. “Makes me feel as if I am doing bad.” 8. “Worry [it would] make my child insecure.” Obese 9. “I don’t like the word, sounds like for an animal.” 10. “Just sound [sic] demeaning.” 11. “Unprofessional, insensitive.” |

Sobrepeso 16. “Hará que mi niño se sienta mal…Afecta el autoestima.” (It would make my child feel bad…It would affect their self-esteem). Obeso 17. “Me suena a una persona adulta.” (It sounds more like it would be referring to an adult). 18. “No me gusta a mi porque el paciente se puede sentir herido y podría causarle traumas psicológicos.” (I do not like it because the patient might feel hurt and it may cause psychological problems). |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study was the first to assess Latino parents’ perceptions of weight counseling terms in Spanish and English. Parent rating of English and Spanish terms’ desirable, motivating, and offensive qualities, which we further examined by parent and child characteristics, can guide clinicians toward selecting optimal weight counseling terms. In English, “unhealthy weight” and “too much weight for his/her health” were rated by parents as the most motivating and among the most desirable and least offensive terms. Additionally, parent perceptions of the phrase “too much weight for his/her health” varied minimally across parent and child demographics, suggesting it could be perceived favorably by many Latino families.

Latino parents completing the Spanish survey rated “demasiado peso para su salud” and “demasiado peso para su edad” as the most motivating and among the most desirable and least offensive terms studies. In the adjusted multivariable models, perception of these terms did vary across a few parent characteristics, indicating that some parents may endorse different perceptions of these terms. However, there was no obvious pattern to the results (there was no dose effect for education, for example, or consistency among one subset of parents). Meanwhile, the analysis of the open-ended question from this survey and our previous focus groups findings can provide context for interpreting these quantitative results.25 Both highlight parental interest in having weight counseling terms and phrases connect to the child’s health, suggesting that the phrase “demasiado peso para su salud” is likely to be received as desirable, motivating, and inoffensive when used in child weight counseling with Spanish-speaking Latino families.

None of the English or Spanish clinical terms referring to body mass index (“high BMI” or “índice de masa corporal alta”) or growth chart weight categories (“overweight,” “obese,” “extremely obese” and “sobrepeso” and “obeso”) were rated as motivating or desirable. In several multivariable models, we found that higher parent educational attainment was associated with viewing some terms more favorably (as more desirable, more motivating, and/or less offensive). This was particularly true for “overweight” and “índice de masa corporal alta,” further suggesting that these terms may not be optimal terms for use in broader Latino populations.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, this is a survey study using a hypothetical scenario rather than assessing parental reactions to the use of terms in an actual encounter. This hypothetical framework asked parents to imagine their child as overweight and may have been understood differently by some parents. Further, many factors, such as the quality and length of provider–parent interactions and relationship, provider–parent language concordance, and use of motivational interviewing were not captured in this study. Second, our participant sample was almost exclusively low-income families of Mexican origin; other diverse Latino populations may have different perceptions of these terms. The high concordance between language preference and responses to the SASH acculturation measure limited our ability to analyze the relationship between acculturation and language-specific term preference.33,34 Also, our ability to detect small differences in term preference by parent and child characteristics may have been limited by our sample size, though our a priori sample size projection was achieved. Although we examined perceptions of 23 terms, our lists were not exhaustive, and additional terms in both languages may warrant examination. Last, although our project used a mixed-methods exploratory sequential study design to use focus groups to inform survey design, additional explanatory qualitative analysis of survey responses was limited to a single open-ended question on the survey itself, thus limiting the depth of interpretation to only what the parent noted about that specific term.

Despite these limitations, our results can help guide providers in counseling Latinos of Mexican background and provide an approach that can be used to identify appropriate and effective terms for speakers of other languages. Future research should also consider assessing the effect of using well-received terms on parent and child motivation and on child BMI outcomes.

Conclusions

The commonly used clinical terms “overweight” and “high BMI,” as well as their Spanish equivalents, “sobrepeso” and “índice de masa corporal alta,” were not rated as highly motivating or desirable among Latino parents, suggesting that these terms may not be optimal choices for weight counseling. Latino parents rated “too much weight for his/her health,” “unhealthy weight,” and “demasiado peso para su salud” as desirable for providers’ use, highly motivating, and inoffensive. Parents explained that terms that link weight status to health are motivating and easily understood, echoing our previous focus group findings25 and further supporting the conclusion that “demasiado peso para su salud” may be the most effective choice for pediatric weight counseling among Spanish-speaking Latino families. Likewise, the English equivalent, “too much weight for his/her health” varied minimally by parent and child characteristics, suggesting it may also be perceived favorably by many Latino families.

What’s New.

Latino parents prefer health care providers use the motivating and inoffensive phrases “unhealthy weight” and “too much weight for his/her health” in English and “demasiado peso para su salud” in Spanish during pediatric weight counseling.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the Kaiser Permanente Colorado Community Benefit Program and in-kind support from Denver Health. Ms Knierim received support from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Scholars Program, funded by Agency for Healthcare Research Quality R24 grant 4R24HS022143, and a Primary Care Research Fellowship, funded by Health Resources and Services Administration grant 5, for analysis and document preparation. During the article’s preparation, Dr Haemer was receiving support from K23 DK104090-01.

Dr Hambidge has received royalties unrelated to this study from Elsevier for editing a general pediatric textbook.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Parental perceptions of weight terminology that providers use with youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e786–e793. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, et al. Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(suppl 4):S229–S253. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgibbon ML, Beech BM. The role of culture in the context of school-based BMI screening. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 1):S50–S62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3586H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Minority Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. The National CLAS Standards. 2013 Available at: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=53. Accessed September 16, 2017.

- 6.Bender MS, Clark MJ. Cultural adaptation for ethnic diversity: a review of obesity interventions for preschool children. Calif J Health Promot. 2011;9:40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow SE, Expert Committee Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(suppl 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkin SL, Gesell SB, Po’e EK, et al. Culturally tailored, family-centered, behavioral obesity intervention for Latino-American pre-school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:445–456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falbe J, Cadiz AA, Tantoco NK, et al. Active and healthy families: a randomized controlled trial of a culturally tailored obesity intervention for Latino children. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Mitchell KF, et al. Parental perceptions of overweight counseling in primary care: the roles of race/ethnicity and parent overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1794–1801. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hambidge SJ, Emsermann CB, Federico S, et al. Disparities in pediatric preventive care in the United States, 1993–2002. Arch Pediatr Acad Med. 2007;161:30–36. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Quintero C, Berry EM, Neumark Y. Limited English proficiency is a barrier to receipt of advice about physical activity and diet among Hispanics with chronic diseases in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1769–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breitkopf CR, Egginton JS, Naessens JM, et al. Who is counseled to lose weight? Survey results and anthropometric data from 3,149 lower socioeconomic women. J Commun Health. 2012;37:202–207. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9437-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branner CM, Koyama T, Jensen GL. Racial and ethnic differences in pediatric obesity-prevention counseling: national prevalence of clinician practices. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:690–694. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2001–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikhailovich K, Morrison P. Discussing childhood overweight and obesity with parents: a health communication dilemma. J Child Health Care. 2007;11:311–322. doi: 10.1177/1367493507082757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turer CB, Montano S, Lin H, et al. Pediatricians’ communication about weight with overweight Latino children and their parents. Pediatrics. 2014;134:892–899. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadden TA, Didie E. What’s in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:1140–1146. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tailor A, Ogden J. Avoiding the term “obesity”: an experimental study of the impact of doctors’ language on patients’ beliefs. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolling C, Crosby L, Boles R, et al. How pediatricians can improve diet and activity for overweight preschoolers: a qualitative study of parental attitudes. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutton GR, Tan F, Perri MG, et al. What words should we use when discussing excess weight? J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:606–613. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.05.100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eneli IU, Kalogiros ID, McDonald KA, et al. Parental preferences on addressing weight-related issues in children. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46:612–618. doi: 10.1177/0009922807299941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volger S, Vetter ML, Dougherty M, et al. Patients’ preferred terms for describing their excess weight: discussing obesity in clinical practice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:147–150. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puhl R, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Motivating or stigmatizing? Public perceptions of weight-related language used by health providers. Int J Obes. 2013;37:612–619. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knierim SD, Rahm AK, Haemer M, et al. Latino parents’ perceptions of weight terminology used in pediatric weight counseling. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turer CB, Barlow SE, Montano S, et al. Discrepancies in communication versus documentation of weight-management benchmarks: analysis of recorded visits with Latino children and associated health-record documentation. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017;4 doi: 10.1177/2333794X16685190. 2333794X16685190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turer CB, Upperman C, Merchant Z, et al. Primary-care weight-management strategies: parental priorities and preferences. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabow P, Eisert S, Wright R. Denver Health: a model for the integration of a public hospital and community health centers. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:143–149. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-2-200301210-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell J. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, et al. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh R, Coyne LS, Wallace LS. Brief screening items to identify Spanish-speaking adults with limited health literacy and numeracy skills. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:374. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace PM, Pomery EA, Latimer AE, et al. A review of acculturation measures and their utility in studies promoting Latino health. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32:37–54. doi: 10.1177/0739986309352341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, et al. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allison PD. Logistic Regression Using SAS: Theory and Application. 2nd. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosmer DW, Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allison PD. Logistic Regression Using the SAS System: Theory and Application. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]