Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a complex psychiatric condition with high heritability, the genetic architecture of which likely comprises both common variants of small effect and rare variants of higher penetrance, the latter of which are largely unknown. Extended families with high density of illness provide an opportunity to map novel risk genes or consolidate evidence for existing candidates, by identifying genes carrying pathogenic rare variants. We performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) in 15 BD families (117 subjects, of whom 72 were affected), augmented with copy number variant (CNV) microarray data, to examine contributions of multiple classes of rare genetic variants within a familial context. Linkage analysis and haplotype reconstruction using WES-derived genotypes enabled exclusion of false-positive single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), CNV inheritance estimation, de novo variant identification and candidate gene prioritization. We found that rare predicted pathogenic variants shared among ≥3 affected relatives were overrepresented in postsynaptic density (PSD) genes (P = 0.002), with no enrichment in unaffected relatives. Genome-wide burden of likely gene-disruptive variants was no different in affected vs. unaffected relatives (P = 0.24), but correlated significantly with age of onset (P = 0.017), suggesting that a high disruptive variant burden may expedite symptom onset. The number of de novo variants was no different in affected vs. unaffected offspring (P = 0.89). We observed heterogeneity within and between families, with the most likely genetic model involving alleles of modest effect and reduced penetrance: a possible exception being a truncating X-linked mutation in IRS4 within a family-specific linkage peak. Genetic approaches combining WES, CNV and linkage analyses in extended families are promising strategies for gene discovery.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a common, complex psychiatric condition characterized by recurrent fluctuations of mood, often accompanied by psychotic features1. Age of onset is typically in the teenage years or early 20s, although episodes may also first appear in mid-life2. Despite twin and family studies providing evidence for high heritability (H2∼80%)3, the specific genetic factors that increase risk remain largely elusive. Historically, linkage studies of multiplex families failed to identify replicable linkage signals across families, indicating genetic heterogeneity and a complex underlying genetic architecture. More recently, large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have implicated common variants in CACNA1C, ANK3 and ODZ4 as being significantly associated with BD4–6. However, the effect sizes of these common disease-associated variants are small, and when the cumulative effect of thousands of common variants are considered under an additive model they explain only one-fourth of the variance in liability7, suggesting that heritable factors not captured by GWAS may contribute to disease etiology. BD genetic architecture is thus likely to comprise a combination of common and rare variants, across multiple classes of variation, including single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variants (CNVs) and de novo variants, although the relative contribution of each class of variants is unclear. The role of rare CNVs in BD risk is still controversial8–11, and although large rare CNVs (>100 kb) have been implicated in BD susceptibility, their effects seem marginal when compared with schizophrenia10,12.

The rapid development of next-generation sequencing technology has facilitated studies examining the impact of rare SNVs in multiplex or extended BD families, shedding light on pathways and genes that may be implicated in the disease13–18. Ament and colleagues employed a candidate gene and pathway approach, using 41 BD families from the NIMH Genomics Initiative (n = 200 subjects)16, finding rare segregating variants enriched in neuronal ion-channel genes, and discovering rare variant associations with existing candidates (ANK3 and CACNA1C). Goes and colleagues sequenced eight multiplex BD families (n = 36 cases), identifying enrichment of genes harboring damaging SNVs in those genes previously reported to carry de novo mutations in schizophrenia or autism18. Georgi and colleagues sequenced 18 parent–child trios from a large single Old Order Amish pedigree of 388 relatives, finding no convergence of risk loci on particular pathways14. In a study of 79 trios by Kataoka and colleagues, de novo variants were associated with earlier age of onset, and were enriched in previously associated psychiatric risk genes19, consistent with earlier reports of de novo variation playing a role in sporadic cases of autism and schizophrenia20,21. No study has thus far simultaneously examined all classes of DNA variation in a familial context.

We therefore performed a comprehensive analysis of multiple classes of rare DNA variants in 15 Australian multiplex and extended families with a high density of illness (≥4 cases per family) using whole-exome sequencing (WES), augmented by CNV and linkage analysis in order to identify genes and pathways that may contribute to the pathophysiology of BD. We considered: (i) predicted pathogenic SNVs and likely gene-disruptive variants shared in ≥3 affected relatives, as compared with those shared in unaffected relatives; (ii) the impact of genome-wide burden of likely gene-disruptive variants on BD; (iii) de novo variants in familial BD; (iv) the role of rare CNVs; and (v) rare variants with potential higher penetrance under top linkage peaks for individual families.

Materials and methods

Bipolar family and subject selection

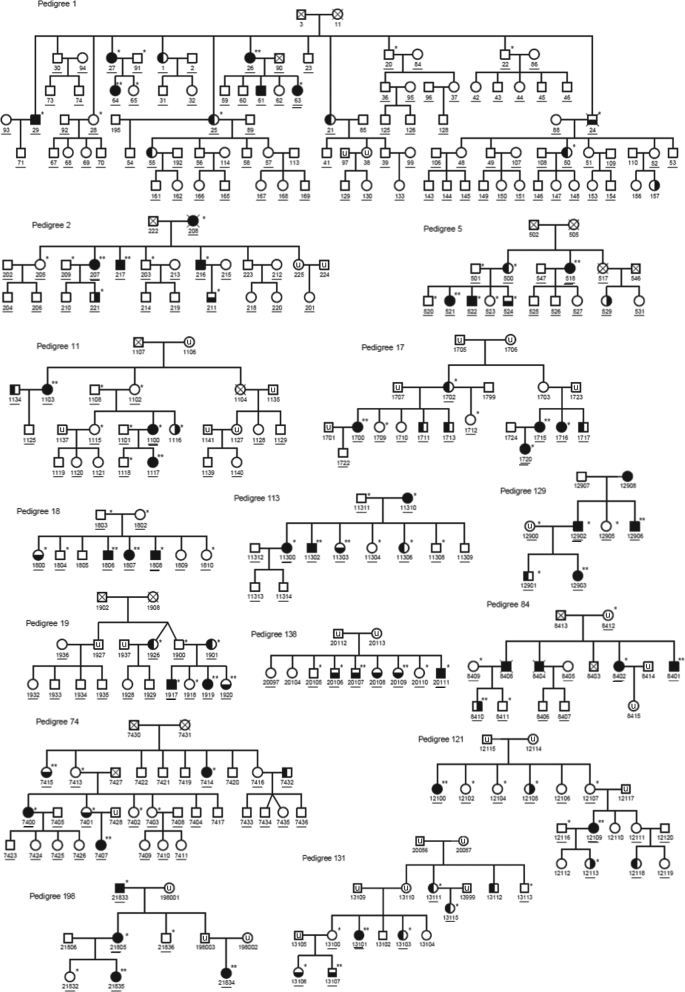

From our collection of 65 multiplex BD families22, we selected 15 extended families of European descent with a high density of illness, as defined by ≥4 first- or second-degree relatives with BD-I, BD-II or schizoaffective disorder-manic type (SZMA) (Fig. 1). Individuals were selected for WES based on diagnostic phenotype, availability and quality of DNA, and pedigree structure using ExomePicks (http://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/ExomePicks). The sequenced sample included 117 subjects: 72 affected relatives, 28 unaffected relatives and 17 unaffected parents. Details on clinical assessments are provided in Supplementary Information (Section 1). Multidimension scaling (MDS) analysis to derive ethnicity from genotype data, examination of genetic relatedness (identity-by-descent (IBD)) analysis to confirm inheritance models and common polygenic risk estimation (PRS) are provided in Supplementary Information (Section 2).

Fig. 1. Structure of the 15 pedigrees examined in our study.

Males are indicated with squares, females with circles, and psychiatric diagnoses are shown by dark shading (full shading = bipolar disorder type I (BD-I), right shading = bipolar disorder type II (BD-II, left shading = recurrent unipolar depression (RUD), bottom shading = schizoaffective disorder-manic type (SZMA), unshaded = unaffected, u = unknown). Individuals included in the exome study are indicated by single asterisks, and subjects with both WES and CytoScanHD array data are indicated by double asterisks. All subjects with DNA available are underlined, and subjects with chip-based genotype data from which multidimensional scaling analysis and polygenic risk scores were generated are indicated with a second underline

Exome capture, sequencing and alignment

Exome enrichment, template sequencing and initial variant calling were performed at the Lotterywest State Biomedical Facility (Perth, Australia). AmpliSeq exome enrichment and Ion Proton sequencing were performed as previously described23. Alignment to human reference genome (hg19:GRCh37.p5) and initial variant calling was performed separately for each individual using Torrent Suite V4.2 (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by a backfilling procedure within Torrent Variant Caller v4.2.3, with ‘hotspot’ parameter set to force genotype calling at all variant sites across all subjects. The mean read depth was very high at 112×, and on average, 92% of bases captured were covered by >10 reads.

Rare variant selection and prediction of pathogenicity

Rare variants were defined as having a European minor allele frequency (MAF) <1% in Exome Variant Server (EVS, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), dbSNP 138 and 1000 genomes Phase I integrated call set. Intersection with Refseq gene models was assessed using Plink-Seq (http://atgu.mgh.harvard.edu/plinkseq/download.shtml), which indicates the ‘worst’ (most damaging) class of functional change where more than one gene model overlaps the variant of interest. Missense variants were annotated using Polyphen 2 HVAR and SIFT from dbNSFP v2.824,25. Polyphen 2 and SIFT scores were combined into a CAROL score, in order to improve effect prediction for nonsynonymous coding variants26, and variants with CAROL ≥0.99 were selected as potentially pathogenic. Likely gene-disruptive variants were defined as nonsense, indels leading to frameshift, canonical splice variants and start-lost.

WES-based linkage analysis, haplotype reconstruction and validation

Genotypes were called from aligned reads using samtools pileup and filtered to include haplotype-informative markers (HapMap CEU population) using LINKDATAGEN27. WES-derived genotypes were used to confirm familial relationships by pair-wise IBD using PLINK28, and also to perform haplotype phasing and linkage analysis in each family under both parametric and non-parametric models using Merlin29. Parameters for linkage analysis, as well as linkage results and SNV colocalization analyses are provided in Supplementary Material (Section 3).

Reconstructed haplotypes were visualized using HaploPainter30, and used to compare against inheritance of all rare potentially pathogenic variants in each family: those inconsistent with underlying haplotype (or where haplotype was uninformative) were validated by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

CNV analysis

Genome-wide CNV analysis was performed via CytoScan® HD Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in two affected relatives per family (n = 30 individuals). All rare CNVs (MAF < 0.05) spanning at least 25 kb (minimum of 25 probes) were considered. We also considered WES-derived genotypes for consecutive Mendelian inconsistencies to identify likely CNV deletions. Additional support of CNVs and pedigree segregation was provided via three complementary methods: (i) analysis of SNP array data (Illumina 660 quad, one patient per family) with PennCNV31; (ii) CNVs derived from WES read depth using EXCAVATOR32; and (iii) using haplotypes to infer CNV segregation among relatives. All CNVs were validated through quantitative PCR (qPCR). Full details of CNV study methods are provided in Supplementary Information in Section 4.

De novo variant analysis

We selected all nuclear families from within the 15 extended families for whom we had WES for both parents and their offspring, regardless of diagnosis. This yielded 32 offspring individuals from 9 of the 15 families for de novo assessment, 22 of which were affected offspring and 10 unaffected offspring (represented in Supplemental Figure S7). All variants with potential Mendelian error from WES genotypes were screened for adequate read depth (AD > 20), and manual checking of reads in both parents and offspring, plus any additional relatives, using IGV v2.3.34 to confirm each putative de novo variant. All putative de novo variants then underwent validation by Sanger sequencing. Full details of de novo study methods are provided in Supplementary Information in Section 6.

Statistical and bioinformatic analyses

Enrichment of genes carrying potentially pathogenic shared rare variants were tested against all gene ontology (GO) categories, and were corrected for multiple testing. In a second analysis, we performed an enrichment analysis against gene sets potentially related to disease pathophysiology, namely: genes encoding postsynaptic density (PSD) proteins33, FMRP interactor targets34, de novo variants in autism, schizophrenia and intellectual disability20, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (NMDARs)20, activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (ARC) complex20, and nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins35. Both analyses were performed by: (i) matching genes carrying potentially etiologic variants to genes with sufficient sequence coverage (>10×) randomly drawn from the genome, after approximate matching on coding-sequence length and genic constraint missense Z-score (http://exac.broadinstitute.org)36; and (ii) calculating an empirical p-value for observed data for each functional category, using a null distribution of overlap counts from 10,000 randomly drawn gene sets. Empirical p-values that exceed Bonferroni correction for multiple testing for were considered significant.

Non-parametric and mixed-model tests were performed to assess differences in the number and distribution of likely gene-disruptive variants between BD patients and their unaffected relatives. Spearman’s correlation was performed to assess the relationship between likely gene-disruptive variants and age of onset (n = 58 subjects).

Genes expressed in the brain were determined from RNA-seq data downloaded from the developmental transcriptomics data, generated across 13 developmental stages in 8–16 brain structures (http://www.brainspan.org/rnaseq/search/index.html). Normalized expression values were examined, using reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM), and those genes with an average RKPM > 1 across all samples (either across all ages and brain tissues, or limited to only prenatal or adult expression) were considered brain expressed.

Evidence of gene-level association with BD and schizophrenia was derived from summary statistics from Psychiatric Genomics Consortium GWAS6,37, with VEGAS2 (https://vegas2.qimrberghofer.edu.au/). Additional methods for enrichment and linear regression analyses is provided in Supplementary Material in Section 5.

Results

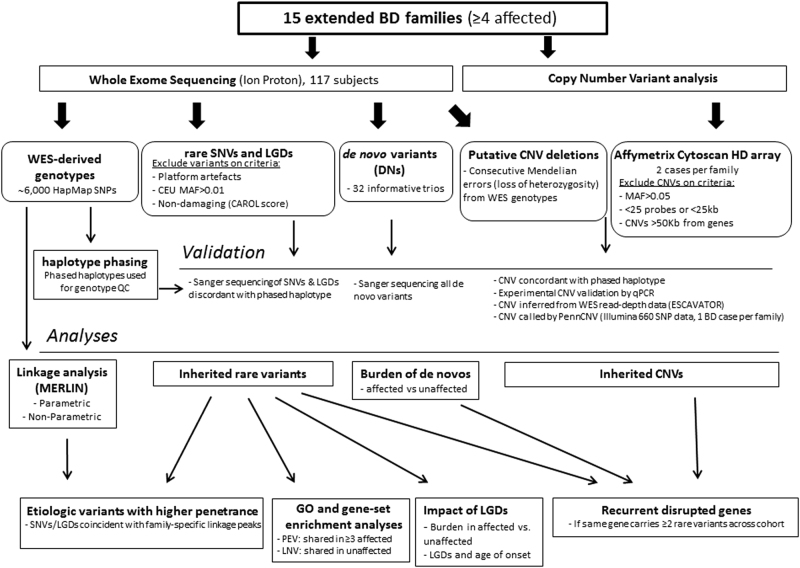

WES was performed on 117 individuals from 15 Australian multiplex and extended BD families of European origin with a high density of illness, as defined by ≥4 relatives with BD-I, BD-II or SZMA (Fig. 1). Familial relationships between sequenced subjects were all confirmed at the sequence level using WES-derived genotypes and performing genome-wide IBD analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). Caucasian ethnicity was confirmed by multidimensional scaling analysis of genotype data, as shown in Figure S8. We used a comprehensive analysis approach, examining a range of rare variant classes for their potential role in familial BD: (i) selecting rare (MAF < 0.01) SNVs and likely gene-disruptive variants segregating with BD; (ii) identifying de novo variants; and (iii) examining CNVs (MAF < 0.05, within 50 kb from any coding gene) using combined analyses of CNV microarray and WES-based loss-of-heterozygosity and read depth data plus familial segregation inference. The workflow is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Workflow overview for the current study.

Exclusion and inclusion filters and prioritization criteria for selection of the final pool of rare single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variants (CNVs) and de novo (DN) variants are described. WES whole-exome sequencing, NPL non-parametric linkage, QC quality control, LGDs likely gene-disruptive variants, GO gene ontology, PEV potentially etiologic variant, LNV likely neutral variant

Selection of inherited rare SNVs and enrichment analysis

As penetrance of rare alleles and degree of polygenicity is heterogeneous for psychiatric disease, ranging from an oligogenic model comprising a small number of highly penetrant variants to a fully polygenic model comprising a larger number of less penetrant genes, we considered different degrees of rare variant sharing to identify potentially etiologic variants under both models. For each family, we considered two categories of rare variants: (1) SNVs or likely gene-disruptive variants shared in a minimum of three affected relatives and a maximum of one unaffected relative, which are potentially etiologic variants; and (2) SNVs shared in up to three unaffected relatives and a maximum of one affected relative, which are randomly shared, likely non-pathogenic variants, henceforth described as likely neutral variants. Under these models, 532 potentially etiologic variants (85% missense, 6.5% indel-frameshift, 5% nonsense, 3% splice-site and 0.5% start-lost) and 541 likely neutral variants (86% missense, 5% indel-frameshift, 4.5% nonsense, 4% splice-site and 0.5% start-lost) were identified (Supplementary Table S1).

To assess whether the pool of potentially etiologic variants were overrepresented in genes potentially involved in BD pathogenesis, we performed an enrichment analysis with gene sets previously implicated in studies of schizophrenia and BD18,20,38. The same analysis was performed with likely neutral variants as a control gene pool. Genes containing potentially etiologic variants were found to be enriched in the PSD33 (empirical P = 0.002, Bonferroni corrected P = 0.024), which was the only gene set showing significant enrichment after correction for gene length, genic tolerance and sequence coverage (Table 1). As expected, likely neutral variants were not enriched for any gene sets. GO analysis of potentially etiologic variants genes found interesting functions in the top enriched categories after correction for gene length, genic tolerance and sequence coverage (e.g., ligand-gated sodium channel activity, uncorrected empirical P = 0.0092), but none were significant after multiple testing correction (data available upon request).

Table 1.

Enrichment analysis of predicted pathogenic rare variants shared in affected or unaffected relatives, after combining data across 15 Australian BD families

| PEVs (498 genes) | LNVs (495 genes) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene set (n genes) | O (E) | P-val (corr P-val) | O (E) | P-value (corr P-val) |

| PSD (1445) | 59 (41.5) | 0.002 (0.024) | 40 (38.5) | 0.423 (1) |

| FMRP targets (837) | 44 (39.6) | 0.218 (1) | 44 (38.2) | 0.143 (1) |

| De novo PSY (1627) | 71 (66.2) | 0.254 (1) | 67 (68.7) | 0.627 (1) |

| NMDARs (61) | 2 (1.7) | 0.527 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.321 (1) |

| ARC (27) | 0 (0.5) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.7) | 0.541 (1) |

| Mitochondrial (1124) | 22 (24.3) | 0.727 (1) | 21 (22.6) | 0.679 (1) |

Hypergeometic p-value, examining hits per category unadjusted for gene length, genic intolerance or sequence coverage of reference genes; AdjP-value, examining hits per category after adjustment for gene length, genic intolerance and sequence coverage of reference genes; AdjP-values that exceed Bonferroni correction for 12 independent tests are indicated in bold

PEVs potentially etiologic variants, which were shared in ≥3 affected relatives ± one unaffected relative (Supplementary Table S1), LNVs likely neutral variants were shared in 1 to 3 unaffected ± an affected relative (Supplementary Table S1), O number of genes observed in this category, E number of genes expected in this category, PSD genes expressed in the postsynaptic density33, De novo PSYCH de novo variants found in autism, schizophrenia and intellectual disability20, NMDARs N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor gene set20, ARC activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein gene set20, Mitochondrial autosomal genes encoding mitochondrial localized proteins35

Although recessive rare variants were not expected (or observed) in these non-consanguineous families, we did observe compound heterozygous variants in two genes: two missense SNVs (rs200385024 and rs199673743) were observed in HYDIN gene in a single BD-I patient (PED_74-7400); and two frameshift-indels leading to a knock-out of DNAH14 were observed in two affected relatives (PED_19-1917 and PED_19-1920, BD-I and SZMA, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S2).

Impact of likely gene-disruptive SNVs on BD diagnosis and age of onset

To understand whether genome-wide burden of truncating variants plays a role in BD, we selected all likely gene-disruptive variants for each individual, independently of their familial segregation (n = 546 variants). Using a non-parametric test, we examined differences in the genome-wide burden of likely gene-disruptive variants between affected and unaffected relatives (Supplementary Figure S3). We found no significant difference in the total number of likely gene-disruptive variants between the two groups (mean ± SD = 13.1 ± 3.21 and 13.8 ± 3.17, respectively; Mann–Whitney U-test = 1361, two-tailed P = 0.24), nor when we restricted to those variants in brain-expressed genes (P = 0.17). Mixed-model analyses showed similar results (total, P = 0.33; brain expressed, P = 0.26). Furthermore, although underpowered for statistical analysis, of the 15 subjects with full GWAS data for whom polygenic risk scores (PRSs) could be calculated using previously identified common BD risk variants (most of which are noncoding), we observed no obvious relationship between the number of likely gene-disruptive variants and BD polygenic risk score (PRS in top 50% vs. bottom 50%: mean ± SD = 13.42 ± 4.61 vs. 13.12 ± 2.79, respectively; quintiles: mean ± SD = 14.75 ± 5.85 vs. 12.33 ± 3.06).

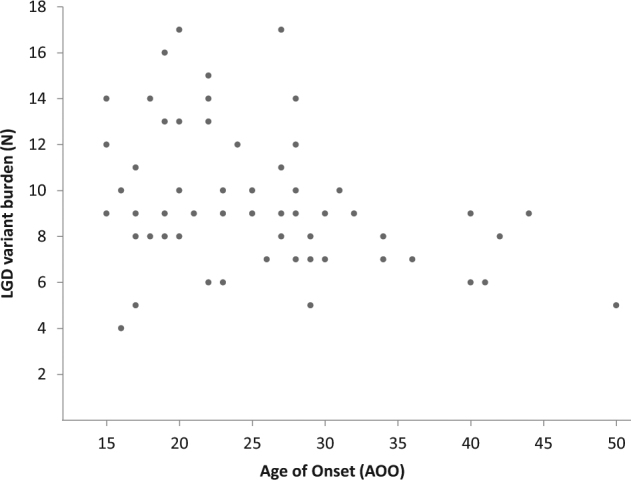

We next investigated whether earlier manifestation of symptoms correlated with an accumulation of likely gene-disruptive variants in brain-expressed genes. A Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between the number of likely gene-disruptive variants and age of onset. In 58 cases with broadly defined BD and typical onset (15–50 years)2, we found age of onset was negatively correlated with the number of brain-expressed likely gene-disruptive variants (rs(58) = –0.312; P = 0.017), with a higher burden of variants in patients with earlier symptom onset (Fig. 3). Similar findings were obtained when limiting analysis to patients with more severe forms of illness (BD-I/SZMA, n = 48; rs = –0.325; P = 0.024).

Fig. 3. Higher burden of disruptive variants in brain-expressed genes relates to earlier age of onset.

Correlation analysis was performed examining relationship between age of onset (AOO, x axis) and genome-wide burden of likely gene-disruptive (LGD) variants in brain-expressed genes (y axis). A total of 58 individuals affected with BD-I (n = 36), SZMA (n = 12), BD-II (n = 4) or RUD (n = 6), with typical age of onset (15–50 years) were considered

Role of inherited CNVs in familial BD

To assess whether structural variants contribute to risk of BD, we performed high-density array-based CNV analysis in two relatives per family, augmented with deletions from WES-derived genotype data. We then inferred familial segregation using phased haplotypes, and validated CNVs with SNP array data, read depth information and finally qPCR. We found 17 rare inherited CNVs in 15 loci across the genome (Supplementary Table S2). Three families harbored CNVs affecting the protocadherin alpha (PCDHA) gene cluster (Supplementary Figure S4), and two families with CNVs affecting the contiguous PRODH and DGCR5 genes. Although not segregating closely with BD, we identified CNVs affecting intronic regions of candidate genes previously implicated in psychiatric disorders (i.e., NLGN1, CNTNAP2, KCNB2 and CNTN5), each in different families. These data provide additional corroborating evidence of their potential role in disease.

Potentially etiologic SNVs and CNVs co-incident with linkage peaks

Linkage analysis using WES-derived genotypes may refine genomic intervals to identify putative highly penetrant etiologic variants. Thus, we performed parametric and non-parametric linkage for each family (Supplementary Information), and examined potentially etiological variants and CNVs, which coincide with family-specific linkage peaks to identify candidate genes for BD.

We found CNV duplications segregating with BD under the highest family-specific linkage peak in two families: one spanning PDZD2 and GOLPH3 (PED_5, hg19/chr5:32109541-32170613bp); the other spanning AMICA1, MPZL3, MPZl2 and CD3E (PED_121, hg19/chr11:118081344-118195313bp) (Supplementary Table S2). The evidence of family-specific linkage at each SNV site is described in detail in Supplementary Material Section 3. In summary, the most promising etiological variants co-incident with family-specific linkage peaks (logarithm of the odds of linkage (LOD) ≥ 1.5) were: (1) a missense variant (rs61746994) in TNS1 (PED_2, parametric LOD = 1.79); (2) an indel-frameshift variant (rs577236284) in the penultimate exon of DLEC1 (PED_5, non-parametric ExLOD = 1.78); (3) a missense variant (rs9332239) in CYP2C9 (PED_5, non-parametric ExLOD = 1.79); and finally, (4) a novel nonsense mutation (p.891 R > X, hg19/chrX:107976904 bp) in IRS4 (PED_138, parametric LOD = 1.5) (Supplementary Figure S5A). The IRS4 protein-truncating variant was genotyped by Sanger sequencing in all available family members, and found in all five affected siblings, as well as the youngest of three unaffected siblings (Supplementary Figure S5). Using immortalized lymphocyte cell lines from this family, we found that nonsense-mediated mRNA decay did not degrade the mutant transcript (Supplementary Figure S6).

De novo variant load in familial BD

De novo variants may explain some of the missing heritability in sporadic cases19, but their impact in the context of familial BD is largely unexplored. Thus, we examined de novo variant load in 32 sequenced parent–child trios, which included 22 BD and 10 unaffected offspring (Supplementary Figure S7). We found 63 putative de novo variants, of which 45 (73%) validated by Sanger sequencing, including 31 coding variants (Supplementary Table S3) and 14 noncoding variants of unknown functional impact. We found no difference in the coding of de novo variant load between affected and unaffected offspring (n = 20/22 vs 11/10 coding variants; Mann–Whitney U-test P = 0.89, average of 0.97 observed per individual). Interestingly, we identified non-conservative de novo variants in a number of genes, including the PC gene (nuclear-encoded mitochondrial pyruvate carboxylase) (p.384Ala > Thr) and MAP4 (microtubule-associated protein 4) (p.425Ile > Met), in a BD-I and SZMA patient respectively. We also identified variants in BD offspring, which included a nonsense de novo mutation in BMP1, and a missense predicted pathogenic variant in transcription factor PHTF1.

Gene convergence across all variant classes

To identify potential candidate genes accumulating recurrent rare mutations across different variant classes, we examined genes harboring ≥2 putative damaging rare variants, which were shared in ≥3 affected relatives. These data were integrated with additional evidence for involvement in BD pathogenesis, including brain expression and gene-based evidence of common variant association with BD6 or schizophrenia37 as calculated using VEGAS2 (Table 2). Genes accumulating more evidence of putative involvement in BD were members of the protocadherin alpha cluster. Two genes, which are expressed in the PSD, also had recurrent mutations: the nuclear mitochondrial proline dehydrogenase gene PRODH and the extracellular matrix protein gene TNC.

Table 2.

Recurrent SNV, CNV, de novo and likely gene-disruptive variations, found at least twice per gene

| Gene | ExAC (z-score) | PED (N) | N variants (type) | N aff (unaff) relatives | PGC1-BD VEGAS P | PGC2-SCZ VEGAS P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANGPTL5 NB | −1.85 | 2 | 1 SNV (mis) | 6 (2) | 0.045 | 0.863 |

| DGCR5 | ND | 2 | 2 CNVs (dup, del) | 8 (2) | 0.611 | 0.125 |

| DNAH14 NB | −0.68 | 1 | 2 SNVs (fs) | 4 (1) | 0.201 | 0.338 |

| FAT2 | −1.01 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 6 (2) | 0.791 | 0.22 |

| HECTD4 | 6.77 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 7 (1) | 0.367 | 0.146 |

| HYDIN | ND | 3 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 9 (2) | 0.651 | 0.009 |

| KIAA1731 | −0.18 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 8 (1) | 0.654 | 0.955 |

| MAP4 | −0.94 | 3 | 1 SNV (mis); 1 DN (mis) | 5 (1) | 0.61 | 0.032 |

| MIA3 | −1.43 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 6 (0) | 0.111 | 0.027 |

| MUC5B NB | 6.3 | 5 | 6 SNVs (mis) | 10 (8) | 0.254 | 0.08 |

| NEB NB | −3.74 | 3 | 4 SNVs (mis) | 9 (3) | 0.098 | 0.033 |

| NRG1 | 0.62 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 6 (1) | 0.232 | 0.47 |

| OBSCN | −1.17 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 6 (2) | 0.947 | 0.289 |

| PCDHA8 | 2.24 | 3 | 3 CNVs (del) | 9 (1) | 0.022 | 6.10E-05 |

| PCDHA9 | 2.28 | 3 | 3 CNVs (del) | 9 (1) | 0.02 | 7.20E-05 |

| PCDHA10 | 1.2 | 2 | 2 CNVs (del) | 7 (1) | 0.023 | 8.30E-05 |

| PCDH15 | −2.88 | 3 | 3 SNVs (mis) | 9 (2) | 0.101 | 0.042 |

| PRODH | 0.77 | 2 | 1 SNV; 2 CNVs (dup, del) | 9 (3) | 0.934 | 0.451 |

| PRUNE2 | −1.48 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 7 (0) | 0.427 | 0.728 |

| SCN10A NB | −1.8 | 2 | 4 SNVs (mis) | 7 (4) | 0.291 | 0.089 |

| SETX | −1.62 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 8 (1) | 0.085 | 0.479 |

| SLC5A10 | 0.23 | 1 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 3 (1) | 0.061 | 0.002 |

| SOGA1 | 2.17 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 7 (1) | 0.358 | 0.089 |

| TNC | −0.12 | 3 | 3 SNVs (mis) | 8 (3) | 0.367 | 0.055 |

| TTN NB | −4.93 | 7 | 13 SNVs (mis) | 19 (7) | 0.014 | 0.16 |

| VMAC | 0.81 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 7 (1) | 0.002 | 0.32 |

| XDH NB | −2.01 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis) | 6 (0) | 0.466 | 0.434 |

| ZNF506 | 0.09 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis, fs) | 6 (1) | 0.43 | 0.221 |

| ZNF812 NB | −4.76 | 2 | 2 SNVs (mis, fs) | 7 (1) | 0.851 | 0.639 |

For each gene, a measure of functional constraint in the form of ExAC missense z-score36 is provided. The number of pedigrees (PED N) with converging evidence for each gene is given, along with the number and type of variant identified (SNV single-nucleotide variant, CNV copy number variant, DN de novo variant, mis missense, fs frameshift, dup duplication, del deletion). The total number of affected relatives (N aff) and total number of unaffected relatives (N unaff) who carry a variant in the gene are indicated. Evidence of gene-level association with BD and schizophrenia was derived from summary statistics from Psychiatric Genomics Consortium GWAS6,37 with VEGAS2, where p-values < 0.05 are indicated in bold text. Postsynaptic density (PSD) gene names33 are indicated in bold. NB, genes with negligible expression in the brain (RPKM < 1 in developmental transcriptomics RNA-seq data; http://www.brainspan.org/rnaseq/search/index.html). Further information on variants described above is reported in Supplementary Table S1, S2 and S3

Discussion

Sequencing studies of extended BD families have recently suggested that rare variants contribute to the genetic architecture of this complex heritable condition13–18. To further elucidate novel genes and pathways important in disease risk, we performed WES in 15 extended and multiplex families with BD, selected for highly penetrant forms of illness. We extensively assessed the impact of inherited SNVs, likely gene-disruptive variants and CNVs, in conjunction with family-specific linkage, as well as examining the role of de novo variants in familial BD.

The pool of genes containing inherited single-nucleotide potentially etiologic variants, shared in three or more affected relatives, was enriched among those expressed in the PSD33, a structure with biological significance for BD. This enrichment was absent in the comparator likely neutral variant gene pool, potentially indicating specificity of enrichment to BD diagnosis. PSD regulates synaptic plasticity and crosstalk in glutamate-dopamine neurotransmission39,40. The PSD genes are extremely sequence conserved, and comprise scaffolding proteins, such as SHANK3 and NRXN1 genes, which are recurrently described with mutations in autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia41–43. Another PSD gene, ANK3, is one of the most replicated associations for BD6,44. Furthermore, pathway analysis of common variants from GWAS data have implicated PSD genes as having a prominent role in schizophrenia and BD45,46. Therefore, our data add to growing evidence that cumulative pathogenic rare variants in several PSD genes may impair synaptic homeostasis, with effects across multiple psychiatric conditions.

Consistent with early linkage studies, we did not observe clear examples of variants of large effect that co-segregate precisely with BD. Taking the findings from the current and previous studies13–18, the most plausible genetic model would implicate the additive effect of both common and rare variants from a large number of genes, with risk alleles not fully penetrant and not perfectly segregating with disease. Futhermore, we see little relationship between polygenic risk score and the numbers of putative rare variants identified, although our analysis was limited to PRS from a single member of each family and thus only allowed for descriptive assessment of this relationship. As expected in non-consanguineous families, we found little evidence of rare recessive variants, but did observe interesting compound heterozygous likely gene-disruptive variants in DNAH14, although this gene is not highly brain expressed. Although recessive rare genotypes should not be discarded, they are unlikely to play a significant role in BD, as suggested from previous studies in schizophrenia47–49.

Recent sequencing studies in autism spectrum disorder showed a higher burden of de novo or inherited likely gene-disruptive variants both in trios or multiplex families50–53, and overall burden of severe gene-disruptive mutations has been correlated with disease severity52. The impact of likely gene-disruptive variant burden in severity of BD is relatively unexplored, but a study of 79 sporadic parent–child trios showed that increased gene-disruptive de novo variant load was associated with greater symptom severity and earlier age of onset of BD19. Although we found no difference in the total number of de novo variants between BD affected vs. unaffected offspring, a tendency toward a higher rate for predicted pathogenic de novo variants in affected offspring suggests that further studies are needed to understand the implications for de novo variants in BD, both in apparently sporadic and familial contexts. Our observed de novo rate (∼0.97) was in line with rates reported previously (∼0.89–0.94)19,20. Our very high sequence converge (120×) may have resulted in our de novo rate lying in the upper range of those previously reported values. We did not attempt to replicate the analysis of Kataoka et al.19 in regards to de novo variant load and symptom severity in BD, due to the low power of our sample (22 cases).

Interestingly, we observed convergence of evidence of involvement of MAP4, a PSD gene, which is also an FMRP target, for which de novo missense variant has previously been reported in ASD20. In MAP4, we observed both a missense de novo variant and an inherited pathogenic missense variant in patients with schizoaffective disorder. Another de novo variant was found in the PC gene, which maps to 1 of the 30 loci with significant BD association from the second Psychiatric Genomics Consortium GWAS (rs7122539, p = 3.80E-08)54, and produces a protein, which catalyzes the carboxylation of pyruvate to oxaloacetate, and is involved in insulin secretion and synthesis of the neurotransmitter glutamate.

Early age of onset is one of the clinical features often used to measure disease severity in BD and schizophrenia. Recent studies suggested that early-onset BD cases may be significantly influenced by genetics: increased risk of BD in offspring of parents with early onset55, and an overall heritability of 33% for age of onset in schizophrenia56. Intriguingly, we find that the burden of likely gene-disruptive variants in brain-expressed genes may exert age of onset effects, with higher numbers of disrupted genes among those with earlier onset. This finding is consistent with previous studies that correlated higher rates of CNVs, another class of gene-disruptive variants, with early age of onset in BD8,9,11. It is unclear whether brain-expressed likely gene-disruptive variants represent bona fide etiologic variants for BD, or whether a high burden of this variant class may reduce resilience (e.g., negatively impacting cognitive capacity or plasticity)57, resulting in anticipation.

CNVs represent another class of highly disrupting genomic variants considered herein. We did not examine de novo CNVs in our study, but our data do not support a model involving highly penetrant inherited CNVs with perfect disease segregation in any family, although we do find examples of potentially pathogenic CNVs in affected individuals, which may add to the genomic landscape of risk in BD.

When rare variants of all classes are combined with linkage evidence for each family, the most intriguing result was a protein-truncating mutation in the X-linked gene insulin receptor substrate 4 (IRS4) gene, found in PED_138. The IRS4 mutation was present in all five siblings affected with BP-I or SZMA, as well as the youngest of three unaffected siblings. This may reflect reduced penetrance, although it should be noted that this unaffected IRS4 p.R891X mutation carrier was aged 2 years younger than the average age of onset in this family at the time of her clinical assessment. Nonsense-mediated RNA decay prevents dominant-negative effects by degrading abnormal transcripts with premature stop mutations58, although single exon genes, like IRS4, are expected to escape nonsense-mediated decay59—which we experimentally confirmed. Although there is little evidence that common variants on the X chromosome are strongly associated with BD60, the contribution of rare X-linked variants has been poorly studied. Several lines of evidence suggest that IRS4 may be a novel candidate for BD: (i) IRS4 is highly conserved, and truncating mutations extremely rare (freq = 4.6E-05; ExAC); (ii) IRS4 expression in the brain is sexually dimorphic61, and largely restricted to the amygdala and ventral hypothalamus62,63, regions responsible for emotional regulation, fear response and nurturing behaviors; (iii) IRS4 stimulates phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/AKT pathway signaling and interacts with ErbB264, a gene significantly associated with BD60; and (iv) insulin-related signaling regulating postsynaptic spine formation has been implicated in obsessive-compulsive disorder65, a psychiatric condition with shared genetic contributors to BD and schizophrenia66. When knocked out, female IRS4-/- mice show reduced nurturing behavior61,67, although extensive behavioral, neuroanatomical and pharmacological response assessments are yet to be made.

Finally, we observed several rare recurrent variations in two interesting loci relevant to BD: the protocadherin alpha (PCDHA) gene cluster, and proline dehydrogenase 1 (PRODH). The PCDHA cluster, expressed in serotonergic neurons68, lies in a 200 kb LD block, which was significantly associated with schizophrenia in the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium GWAS of 36,989 cases and 113,075 controls (max SNP-based p = 4.85E-08)37. Futhermore, several PCDHA members are regulated by miR-1908, a microRNA that was independently associated with BD69, and may suggest functional convergence. PRODH encodes a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein, involved in the catabolism of proline to l-glutamate, which acts as neuromodulator of dopaminergic synaptic transmission. CNVs spanning PRODH are significantly associated with schizophrenia12, and microdeletions including PRODH at 22q11.2 are associated with DiGeorge syndrome70, in which ~30% of patients develop psychotic symptoms and 25% develop schizophrenia71. Furthermore, common functional variants in PRODH have been associated with alterations in prefrontal–striatal brain circuits affecting working memory and cognitive gating72. Therefore, our study provides corroborating evidence of putative involvement of PRODH in BD.

In conclusion, genetic approaches that combine WES-derived SNV, CNV and linkage analyses in extended families are effective in pinpointing genes and pathways that may contribute to the pathophysiology of BD. Our results show rare putatively functional variants in genes previously implicated by GWAS, as well as novel genes whose role in BD is yet to be fully elucidated.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Australian National Medical and Health Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant 1063960 and supported by NHMRC Project Grant 1066177, and Program Grant 1037196. We gratefully acknowledge the Janette Mary O’Neil Research Fellowship (to JMF) and Mrs. Betty Lynch for supporting this work. DNA was extracted by Genetic Repositories Australia (GRA; www.neura.edu.au/GRA), an Enabling Facility that was supported by NHMRC Enabling Grant 401184. Samples were prepared and sequenced at the Lottery State Biomedical Genomics Facility, University of Western Australia. We thank our MooDs consortium collaborators Sven Cichon (University of Basel, Switzerland), Franziska Degenhardt and Markus Nöthen (University of Bonn, Germany) for genotyping the Australian BD sample on Illumina 660 quad, which used for CNV calling and polygenic risk score generation. We are grateful to all participants and their families, as well as clinical collaborators who were originally involved in collecting and phenotyping these families, including Laila Tabassum, Adam Wright and Andrew Frankland (UNSW). We would also like to thank Barbara Toson (NeuRA) for support in statistical analyses.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Claudio Toma, Alex D. Shaw.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41398-018-0113-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mitchell PB, et al. Bipolar disorder in a national survey using the World Mental Health Version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview: the impact of differing diagnostic algorithms. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013;127:381–393. doi: 10.1111/acps.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellivier F, et al. Age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder in the USA and Europe. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;15:369–376. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.639801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merikangas KR, Low NC. The epidemiology of mood disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sklar P, et al. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira MA, et al. Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/ng.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Lee SH, et al. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:984–994. doi: 10.1038/ng.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D, et al. Singleton deletions throughout the genome increase risk of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:376–380. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Priebe L, et al. Genome-wide survey implicates the influence of copy number variants (CNVs) in the development of early-onset bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:421–432. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green EK, et al. Copy number variation in bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:89–93. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malhotra D, et al. High frequencies of de novo CNVs in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuron. 2011;72:951–963. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, et al. A pilot study on commonality and specificity of copy number variants in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e824. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruceanu C, et al. Family-based exome-sequencing approach identifies rare susceptibility variants for lithium-responsive bipolar disorder. Genome. 2013;56:634–640. doi: 10.1139/gen-2013-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgi B, et al. Genomic view of bipolar disorder revealed by whole genome sequencing in a genetic isolate. PLoS. Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss KA, et al. A population-based study of KCNH7 p.Arg394His and bipolar spectrum disorder. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6395–6406. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ament SA, et al. Rare variants in neuronal excitability genes influence risk for bipolar disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3576–3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424958112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao AR, Yourshaw M, Christensen B, Nelson SF, Kerner B. Rare deleterious mutations are associated with disease in bipolar disorder families. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;22:1009–1014. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goes FS, et al. Exome sequencing of familial bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:590–597. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kataoka M, et al. Exome sequencing for bipolar disorder points to roles of de novo loss-of-function and protein-altering mutations. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:885–893. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fromer M, et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature. 2014;506:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders SJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fullerton JM, Donald JA, Mitchell PB, Schofield PR. Two-dimensional genome scan identifies multiple genetic interactions in bipolar affective disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todd EJ, et al. Next generation sequencing in a large cohort of patients presenting with neuromuscular disease before or at birth. Orphanet. J. Rare. Dis. 2015;10:148. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0364-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:894–899. doi: 10.1002/humu.21517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFPv2.0: a database of human nonsynonymous SNVs and their functional predictions and annotations. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:E2393–E2402. doi: 10.1002/humu.22376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes MC, et al. A combined functional annotation score for non-synonymous variants. Hum. Hered. 2012;73:47–51. doi: 10.1159/000334984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith KR, et al. Reducing the exome search space for mendelian diseases using genetic linkage analysis of exome genotypes. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R85. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-9-r85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiele H, Nurnberg P. HaploPainter: a tool for drawing pedigrees with complex haplotypes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1730–1732. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K, et al. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magi A, et al. EXCAVATOR: detecting copy number variants from whole-exome sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R120. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayes A, et al. Characterization of the proteome, diseases and evolution of the human postsynaptic density. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:19–21. doi: 10.1038/nn.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darnell JC, et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calvo SE, Clauser KR, Mootha VK. MitoCarta2.0: an updated inventory of mammalian mitochondrial proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1251–D1257. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lek M, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sequeira A, et al. Mitochondrial mutations in subjects with psychiatric disorders. PLoS. ONE. 2015;10:e0127280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Bartolomeis A, Buonaguro EF, Iasevoli F, Tomasetti C. The emerging role of dopamine-glutamate interaction and of the postsynaptic density in bipolar disorder pathophysiology: implications for treatment. J. Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:505–526. doi: 10.1177/0269881114523864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Migaud M, et al. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature. 1998;396:433–439. doi: 10.1038/24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leblond CS, et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK mutations in autism spectrum disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS. Genet. 2014;10:e1004580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gauthier J, et al. De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7863–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906232107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Genovese G, et al. Increased burden of ultra-rare protein-altering variants among 4,877 individuals with schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1433–1441. doi: 10.1038/nn.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muhleisen TW, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals two new risk loci for bipolar disorder. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3339. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pathway Analysis Subgroup of Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Psychiatric genome-wide association study analyses implicate neuronal, immune and histone pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:199–209. doi: 10.1038/nn.3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akula N, Wendland JR, Choi KH, McMahon FJ. An integrative genomic study implicates the postsynaptic density in the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:886–895. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rees E, et al. Analysis of exome sequence in 604 trios for recessive genotypes in schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry. 2015;5:e607. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curtis D. Investigation of recessive effects in schizophrenia using next-generation exome sequence data. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2015, 10.1111/ahg.12109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Ruderfer DM, et al. No evidence for rare recessive and compound heterozygous disruptive variants in schizophrenia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;23:555–557. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Roak BJ, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuen RK, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of quartet families with autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Med. 2015;21:185–191. doi: 10.1038/nm.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toma C, et al. Exome sequencing in multiplex autism families suggests a major role for heterozygous truncating mutations. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:784–790. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krumm N, et al. Excess of rare, inherited truncating mutations in autism. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:582–588. doi: 10.1038/ng.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stahl, E. et al. Genomewide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. bioRxiv 2017, 10.1101/173062.

- 55.Preisig M, et al. The specificity of the familial aggregation of early-onset bipolar disorder: a controlled 10-year follow-up study of offspring of parents with mood disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;190:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hare E, et al. Heritability of age of onset of psychosis in schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010;153B:298–302. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ganna A, et al. Ultra-rare disruptive and damaging mutations influence educational attainment in the general population. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1563–1565. doi: 10.1038/nn.4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurosaki T, Maquat LE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans at a glance. J. Cell. Sci. 2016;129:461–467. doi: 10.1242/jcs.181008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khajavi M, Inoue K, Lupski JR. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates clinical outcome of genetic disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:1074–1081. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou L, et al. Genome-wide association study of 40,000 individuals identifies two novel loci associated with bipolar disorder. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:3383–3394. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu X, et al. Modular genetic control of sexually dimorphic behaviors. Cell. 2012;148:596–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Numan S, Russell DS. Discrete expression of insulin receptor substrate-4 mRNA in adult rat brain. Brain. Res. Mol. Brain. Res. 1999;72:97–102. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(99)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li JY, et al. Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing protein 4 (Asb-4) colocalizes with insulin receptor substrate 4 (IRS4) in the hypothalamic neurons and mediates IRS4 degradation. Bmc. Neurosci. 2011;12:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ikink GJ, Boer M, Bakker ER, Hilkens J. IRS4 induces mammary tumorigenesis and confers resistance to HER2-targeted therapy through constitutive PI3K/AKT-pathway hyperactivation. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13567. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van de Vondervoort I, et al. An integrated molecular landscape implicates the regulation of dendritic spine formation through insulin-related signalling in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41:280–285. doi: 10.1503/jpn.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Costas J, et al. Exon-focused genome-wide association study of obsessive-compulsive disorder and shared polygenic risk with schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e768. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fantin VR, Wang Q, Lienhard GE, Keller SR. Mice lacking insulin receptor substrate 4 exhibit mild defects in growth, reproduction, and glucose homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;278:E127–E133. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.1.E127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katori S, et al. Protocadherin-alpha family is required for serotonergic projections to appropriately innervate target brain areas. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9137–9147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5478-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Forstner AJ, et al. Genome-wide analysis implicates microRNAs and their target genes in the development of bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2015;5:e678. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu H, et al. Genetic variation at the 22q11 PRODH2/DGCR6 locus presents an unusual pattern and increases susceptibility to schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3717–3722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042700699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jolin EM, Weller RA, Weller EB. Psychosis in children with velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome) Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kempf L, et al. Functional polymorphisms in PRODH are associated with risk and protection for schizophrenia and fronto-striatal structure and function. PLoS. Genet. 2008;4:e1000252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.