ABSTRACT

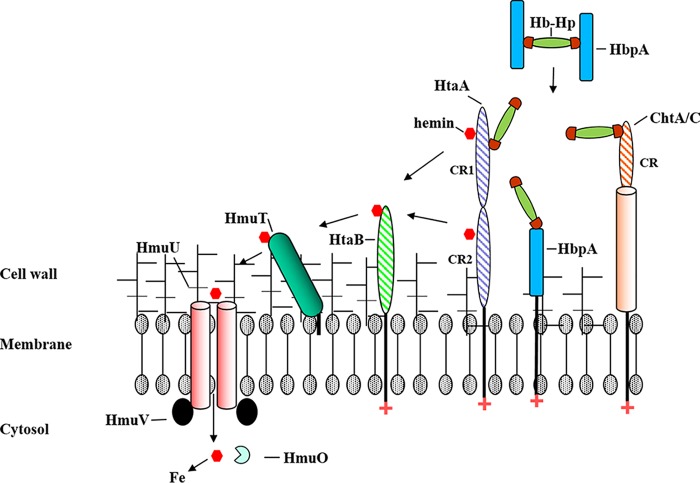

Corynebacterium diphtheriae utilizes various heme-containing proteins, including hemoglobin (Hb) and the hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex (Hb-Hp), as iron sources during growth in iron-depleted environments. The ability to utilize Hb-Hp as an iron source requires the surface-anchored proteins HtaA and either ChtA or ChtC. The ability to bind hemin, Hb, and Hb-Hp by each of these C. diphtheriae proteins requires the previously characterized conserved region (CR) domain. In this study, we identified an Hb-Hp binding protein, HbpA (38.5 kDa), which is involved in the acquisition of hemin iron from Hb-Hp. HbpA was initially identified from total cell lysates as an iron-regulated protein that binds to both Hb and Hb-Hp in situ. HbpA does not contain a CR domain and has sequence similarity only to homologous proteins present in a limited number of C. diphtheriae strains. Transcription of hbpA is regulated in an iron-dependent manner that is mediated by DtxR, a global iron-dependent regulator. Deletion of hbpA from C. diphtheriae results in a reduced ability to utilize Hb-Hp as an iron source but has little or no effect on the ability to use Hb or hemin as an iron source. Cell fractionation studies showed that HbpA is both secreted into the culture supernatant and associated with the membrane, where its exposure on the bacterial surface allows HbpA to bind Hb and Hb-Hp. The identification and analysis of HbpA enhance our understanding of iron uptake in C. diphtheriae and indicate that the acquisition of hemin iron from Hb-Hp may involve a complex mechanism that requires multiple surface proteins.

IMPORTANCE The ability to utilize host iron sources, such as heme and heme-containing proteins, is essential for many bacterial pathogens to cause disease. In this study, we have identified a novel factor (HbpA) that is crucial for the use of hemin iron from the hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex (Hb-Hp). Hb-Hp is considered one of the primary sources of iron for certain bacterial pathogens. HbpA has no similarity to the previously identified Hb-Hp binding proteins, HtaA and ChtA/C, and is found only in a limited group of C. diphtheriae strains. Understanding the function of HbpA may significantly increase our knowledge of how this important human pathogen can acquire host iron that allows it to survive and cause disease in the human respiratory tract.

KEYWORDS: Corynebacterium, haptoglobin, hemoglobin, htaA, iron acquisition

INTRODUCTION

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is the cause of the severe human respiratory disease diphtheria. The bacterium colonizes and replicates in the upper respiratory tract and elaborates the potent exotoxin diphtheria toxin (DT), which is responsible for much of the morbidity associated with this disease (1–3). Transcription of the tox gene, which encodes DT, is regulated by iron with optimal expression occurring in low-iron environments, a condition that is predicted to exist at the site of colonization in the host (2, 4). The iron regulation of tox transcription is mediated by the DtxR repressor, which similarly controls the expression of numerous genes in C. diphtheriae, many of which are involved in iron transport and metabolism (5–8).

The acquisition and utilization of iron are essential for the growth of almost all bacteria and are required by most pathogens to cause disease (9–11). Although essential for virulence, iron is not easily available to invading bacterial pathogens since much of it is sequestered intracellularly by heme, which is bound primarily by hemoglobin (12). In the extracellular environment, much of the iron is bound by the host glycoproteins transferrin and lactoferrin (13, 14). To survive in the iron-limited environment of the host, bacteria have evolved a variety of iron- and heme-scavenging systems, including high-affinity siderophore iron transporters as well as receptor-mediated mechanisms to import hemin through the cell wall and into the cytosol (11, 15, 16).

Bacterial heme transport systems were first identified and characterized in Gram-negative pathogens, such as Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio cholerae, and Neisseria meningitidis, where it was shown that TonB-dependent receptors in the outer membrane could bind hemin or various hemoproteins and mobilize the hemin through the outer membrane into the periplasm (17–20). Once in the periplasmic space, hemin-specific solute binding proteins would bind hemin and deliver it to its cognate ABC transporter in the cytoplasmic membrane (19). Hemin-specific ABC transport systems facilitate the uptake of hemin into the cell, where the heme or heme iron is then made available for cellular metabolism (12). In addition to membrane-binding protein-dependent uptake systems, some Gram-negative bacteria, such as Serratia marcescens and various Pseudomonas species, secrete heme binding proteins, known as hemophores. Hemophores bind to hemoproteins in the extracellular medium, where they extract the heme and deliver it to receptors on the bacterial cell surface (21). The genes encoding many of the different heme uptake systems in Gram-negative bacteria are transcriptionally regulated by iron, which is mediated by the Fur protein, a global iron-dependent regulatory factor that functions in a manner similar to that of DtxR (22).

Hemin transport in Gram-positive bacteria shares some similarities to that of Gram-negative organisms in that both use ABC-type hemin uptake systems to transport hemin through the bacterial membrane (12). However, the binding of hemin and hemoproteins at the cell surface is remarkably different between these groups of bacteria. The most notable difference is that since Gram-positive bacteria lack outer membrane receptors, they interact with hemin and hemoproteins through surface proteins that are tethered to the bacteria either through a covalent linkage to the cell wall that is mediated by sortases or through anchoring to the cytoplasmic membrane by a C-terminal transmembrane domain (12, 23, 24). The hemin transport system in Staphylococcus aureus has been extensively studied and shown to utilize seven surface proteins, designated iron-regulated surface determinants (Isd), to transport hemin (25). The surface-exposed IsdB and IsdH proteins are initially involved in binding hemoglobin (Hb) and the hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex (Hb-Hp) at the surface of the bacteria using unique binding regions known as NEAT (near iron transporter) domains (12, 25–28). These proteins extract the hemin from hemoproteins, where the hemin is subsequently moved through the cell wall by a relay mechanism that involves the cell wall-anchored proteins IsdA and IsdC (29, 30). IsdC transfers hemin to the ABC hemin-specific transporter IsdDEF, which facilitates the movement of hemin into the cytosol (31). Intracellular hemin is either incorporated into heme-containing proteins or is degraded by the heme-degrading mono-oxygenase enzymes IsdG and IsdI, where hemin iron is made available for cellular metabolism (32). The IsdH, IsdB, IsdA, and IsdC proteins are all covalently anchored to the cell wall through the action of sortases (25, 33). The IsdH and IsdB proteins contain multiple NEAT domains that bind either hemin or Hb, while the single NEAT domains in IsdA and IsdC have specificity only for hemin (27, 34–36). Other bacteria that utilize Isd-like proteins for hemin transport include Bacillus anthracis, Listeria monocytogenes, and Streptococcus pyogenes, which express the surface heme-binding proteins Shr and Shp (23, 37–40).

In C. diphtheriae, the acquisition of hemin iron requires the hmu region, which carries genes encoding the ABC-type hemin transporter, HmuTUV, and two hemin-binding proteins, HtaA and HtaB (24, 41). HtaA (61 kDa) is a surface-exposed protein that is tethered to the cytoplasmic membrane through a C-terminal transmembrane region and contains two conserved regions (CR1 and CR2) that bind hemin, Hb, and various other hemoproteins (42, 43). Mutations in htaA and in the hmuTUV genes result in reduced ability of C. diphtheriae to utilize Hb as an iron source (24) but do not fully abolish hemin iron uptake from Hb, which indicates that an alternate mechanism for hemin iron acquisition exists. The binding of hemin and Hb to the CR domains requires a conserved histidine and two conserved tyrosine residues; all three of these residues are also associated with the hemin iron utilization function of HtaA (42). Hemin transfer studies showed that HtaA acquired hemin from Hb in vitro and that the hemin bound to HtaA can be subsequently transferred to HtaB (42). The HtaB protein (36 kDa) contains a single hemin-binding CR domain, and a recent study proposed that HtaB functions as an intermediate in the transport of hemin through the cell wall (24, 42). While the CRs found in Corynebacterium share functional similarities with the NEAT domains present in the Isd proteins and to the Shr or Shp proteins in streptococcal species (24), they lack any significant sequence similarity to the NEAT domains.

We recently described the iron-regulated chtA-chtB and cirA-chtC genetic regions, which are organized as two-gene operons that encode hemin and Hb-binding membrane proteins with sequence similarity to HtaA and HtaB (44). The ChtA and ChtC proteins (83.9 kDa and 74.3 kDa, respectively) contain an N-terminal secretion signal and a C-terminal anchoring region like that found in HtaA (44). Cell fractionation studies show that ChtA and ChtC are present on the membrane and exposed on the cell surface; however, they are also found in the supernatant, suggesting that these proteins are secreted, which could be due to a weak association with the membrane or to natural shedding of the membrane during growth. Both ChtA and ChtC harbor a single N-terminal CR domain that is essential for hemin and Hb binding. The two proteins exhibit significant sequence homology to each other; however, similarity of ChtA and ChtC to HtaA is observed only in the CR domain (44).

A recent study that examined the ability of C. diphtheriae to use various hemoproteins as iron sources showed that C. diphtheriae utilized Hb-Hp, human serum albumin (HSA), and myoglobin (Mb) as hemin iron sources for growth in low-iron medium (43). A deletion mutant of htaA was unable to use Hb-Hp-iron and showed significantly reduced ability to use hemin iron from HSA and Mb. Deletion of the chtA or chtC genes had no effect on the ability of C. diphtheriae to use any of these host iron sources for growth under iron-starved conditions; however, a chtA chtC double mutant was significantly reduced in its ability to use Hb-Hp as an iron source (43). The double mutant was not affected in its ability to use heme iron from Hb, HSA, or Mb. These findings demonstrated that the use of Hb-Hp iron required both HtaA and either ChtA or ChtC (ChtA/C). The mechanism as to how HtaA and ChtA/C function to scavenge hemin iron from Hb-Hp is not known, although it was proposed that these large surface-anchored proteins may form a complex on the cell surface to facilitate the extraction of hemin from the Hb-Hp complex (43). The question as to whether ChtA and ChtC have redundant functions with regard to Hb-Hp iron utilization was not addressed in these earlier reports.

In this study, we have identified an iron-regulated protein, HbpA (previously DIP2330), that is involved in the utilization of Hb-Hp as an iron source. We show that this novel protein is produced in large quantities during growth in low-iron medium and is found on the cell surface and in the culture supernatant. HbpA does not possess a hemin or Hb-binding CR domain but can bind both Hb and the Hb-Hp complex. Surprisingly, recombinant HbpA is unable to bind hemin, a characteristic that is unique among all other previously characterized Hb-binding proteins involved in hemin iron transport. HbpA has sequence homology to proteins found only in certain strains of C. diphtheriae and appears to represent a new class of Hb- and Hb-Hp binding protein.

RESULTS

Identification of a novel Hb-Hp binding protein in C. diphtheriae.

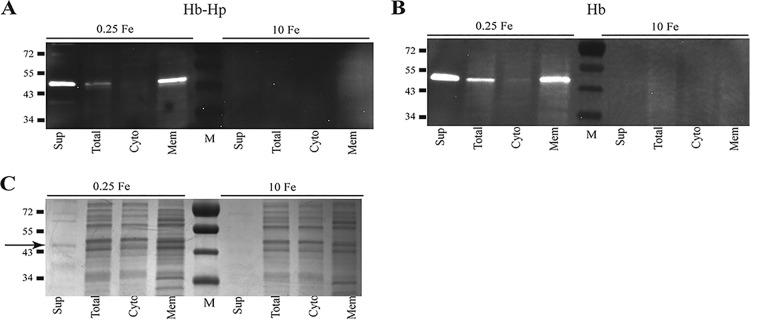

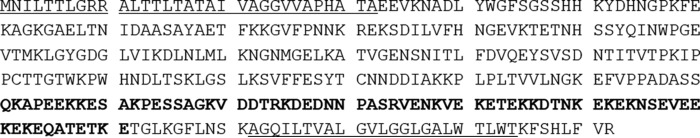

To further understand the interaction of Hb and Hb-Hp with C. diphtheriae surface proteins, we performed studies in which either Hb or Hb-Hp was incubated in situ with C. diphtheriae proteins that had been separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Both Hb and Hb-Hp bound strongly to a single band that migrated at approximately 40 kDa, and this binding was present predominantly in the membrane and supernatant fractions from bacteria grown under low-iron conditions (Fig. 1A and B). Lysates of bacteria grown under high-iron conditions did not bind to either Hb or Hb-Hp (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG 1.

In situ binding of Hb-Hp (A) and Hb (B) to immobilized proteins following cell fractionation of C. diphtheriae 1737. Cellular fractions are indicated as follows: supernatant (Sup), total cell lysate (Total), cytosolic (Cyto), and membrane (Mem). C. diphtheriae 1737 was grown in mPGT medium under low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) and high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) conditions. The binding of Hb-Hp was detected by anti-Hp antibodies and Hb binding was detected using anti-Hb antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE gel containing cell fractions obtained from C. diphtheriae 1737 following growth in low- and high-iron mPGT medium. The arrow indicates the approximately 40-kDa protein band that was excised from the gel and used for LC-MS/MS analysis. Protein sizes are indicated to the left of the gel in kilodaltons, and M represents the molecular mass marker. Experiments were repeated multiple times with similar results; a representative experiment is shown.

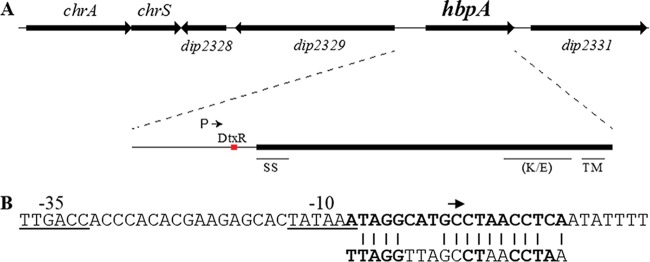

A protein of approximately 40 kDa, which corresponds to the Hb-Hp-binding protein in Fig. 1A, was detected in the supernatant fraction in low-iron cultures following Coomassie blue staining of proteins separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C, band indicated by an arrow). This 40-kDa band was excised from the gel and subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Peptide analysis of the LC-MS/MS results indicated that two putative membrane proteins with a predicted size of approximately 38 kDa were the most likely candidates for the Hb-Hp binding protein; these two proteins are annotated in the genome sequence of C. diphtheriae strain NCTC13129 (45) as DIP2330 and DIP0659 (Table 1). Sequence analysis of the two genes and their upstream regions revealed that only dip2330 (designated hbpA) contained a putative DtxR binding site upstream of the predicted open reading frame, suggesting that hbpA is iron regulated (Fig. 2), which is consistent with the expression observed for the 40-kDa Hb-Hp-binding protein identified in the in situ studies (Fig. 1A).

TABLE 1.

LC-MS/MS results

| Corresponding genea | Protein name (if known) | Description | Score | Coverage (%) | No. of unique peptides | Molecular mass (kDa) | Calculated pI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dip2330 | HbpA | Putative membrane protein | 568.68 | 52.56 | 22 | 38.5 | 6.74 |

| dip0659 | Putative membrane protein | 258.37 | 51.65 | 18 | 38.7 | 5.02 | |

| dip2069 | Putative secreted protein | 54.05 | 17.51 | 6 | 41.9 | 4.79 | |

| dip0522 | ChtC | Putative membrane protein | 17.74 | 10.18 | 5 | 74.3 | 5.49 |

| dip2116 | Putative membrane-anchored protein | 35.00 | 10.67 | 4 | 56.8 | 5.58 |

Gene annotation from C. diphtheriae strain NCTC13129. Genes in boldface were deemed the most likely candidates to encode Hb-Hp-binding proteins.

FIG 2.

(A) Genetic map of hbpA and adjacent genes. The intergenic region upstream of hbpA contains the putative promoter region for hbpA (P) and a DtxR binding site. The signal sequence (SS), the transmembrane region (TM), and the lysine-glutamic acid-rich region (K/E) are also shown. (B) The DNA sequence of the −10 and −35 promoter elements (underlined) and the putative DtxR binding site (bold) upstream of the hbpA gene are shown. The arrow indicates the start site for transcription as determined by 5′ RACE. The 19-bp consensus DtxR binding site is shown below the hbpA DtxR binding site; the most highly conserved residues in the consensus sequence are indicated in bold.

The hbpA promoter is regulated by DtxR and iron.

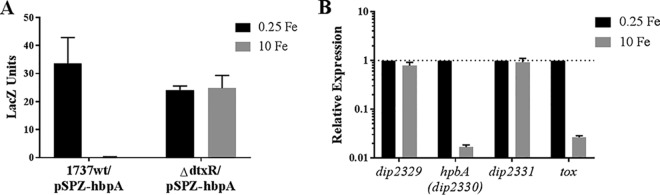

To determine if transcription of hbpA is regulated by iron levels, we moved a DNA fragment containing the hbpA upstream intergenic region into the promoter probe plasmid pSPZ to construct pSPZ-hbpA. Plasmid pSPZ-hbpA was assessed for promoter activity in the C. diphtheriae 1737 wild-type strain and in the isogenic dtxR mutant strain by determining β-galactosidase activity following growth in high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) and low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) medium. The LacZ activity in the wild-type strain showed that transcription was strongly repressed under high-iron conditions and that iron-dependent repression was alleviated in the dtxR mutant strain, a finding consistent with DtxR-mediated regulation of transcription (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Transcription of hbpA is regulated by iron. (A) LacZ activity was measured from cultures of C. diphtheriae wild-type strain 1737 (1737wt) and strain 1737ΔdtxR carrying the promoter probe plasmid pSPZ-hbpA. Strains were grown in high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) and low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) mPGT medium. (B) qPCR was used to directly measure transcription of hbpA and adjacent genes (dip2329 and dip2331) by assessing mRNA levels of C. diphtheriae 1737wt grown under low- or high-iron conditions as described above for the LacZ assays. Analysis of the tox gene was used as a positive control for iron regulation. Expression observed under low-iron conditions is normalized to a value of 1 (shown by a dotted line) for each gene to assess relative expression. Experiments were done at least three times; graphs show means with standard deviations.

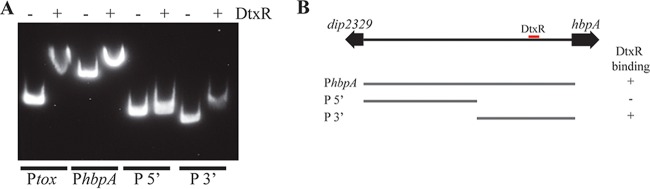

Transcription of hbpA was directly measured by isolating RNA from the wild-type strain grown under high- and low-iron conditions and using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) to assess relative RNA levels for hbpA and adjacent genes. The qPCR findings showed an ∼60-fold reduction in hbpA mRNA when bacteria were grown in high-iron medium compared to growth in low-iron medium (Fig. 3B). The adjacent genes dip2329 and dip2331 were also probed by qPCR and did not show any regulation by iron, indicating that hbpA is likely a monocistronic gene (Fig. 2A). The tox gene, which served as a positive control for iron regulation, was strongly repressed under high-iron conditions, as expected. Further analysis of the hbpA promoter region by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) showed that transcription of hbpA initiates at a C residue located within the DtxR binding site (Fig. 2B). Putative −10 and −35 promoter elements were present at appropriate distances upstream from the transcription start site. Analysis of the DtxR binding site showed that it matched with 14/19 bases of the consensus sequence, which includes most of the highly conserved residues (Fig. 2B). We used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to confirm the binding of DtxR to the hbpA promoter region. Purified DtxR bound to the full-length intergenic region (377 bp, PhbpA) as well as the 3′ 175-bp fragment (P3′) that is predicted to harbor the DtxR binding site, but DtxR failed to bind to the 205-bp fragment in the 5′ region (P5′) (Fig. 4). A DNA fragment carrying the tox promoter (Ptox) served as a positive control for DtxR binding. Together these data indicate that hbpA transcription is regulated in response to iron levels in a DtxR-dependent manner.

FIG 4.

DtxR binds to the hbpA promoter region. (A) EMSA shows that DtxR is able to bind to DNA fragments carrying the putative DtxR binding site upstream of the hbpA gene (PhbpA and P3′). The Ptox DNA fragment was used as a positive control and carries the DtxR binding site for the tox promoter. The presence (+) or absence (−) of DtxR in the binding reaction mixture is indicated above the gel. (B) DNA fragments that were used in the EMSA are shown below a genetic map of the hbpA-dip2329 intergenic region. The location of the DtxR binding site is indicated (red box). The ability or inability of the DNA fragments to bind to DtxR is indicated by a plus sign or a minus sign, respectively.

We observed that hbpA is located near the genes encoding the ChrS/ChrA (ChrS/A) heme-responsive two-component signal transduction system (Fig. 2A). Since the hbpA gene product appears to be associated with Hb and Hb-Hp binding, we analyzed the transcription of hbpA in the presence of Hb, a factor known to activate the regulatory functions of the ChrS/A system (46). While the presence of Hb in the growth medium strongly activated transcription of the hrtAB promoter, a known heme-activated promoter (47), Hb had no effect on transcription from the hbpA promoter on plasmid pSPZ-hbpA, suggesting that transcription of hbpA is not regulated by Hb and likely not affected by the ChrS/A system (data not shown).

HbpA is associated with the membrane and secreted into the medium.

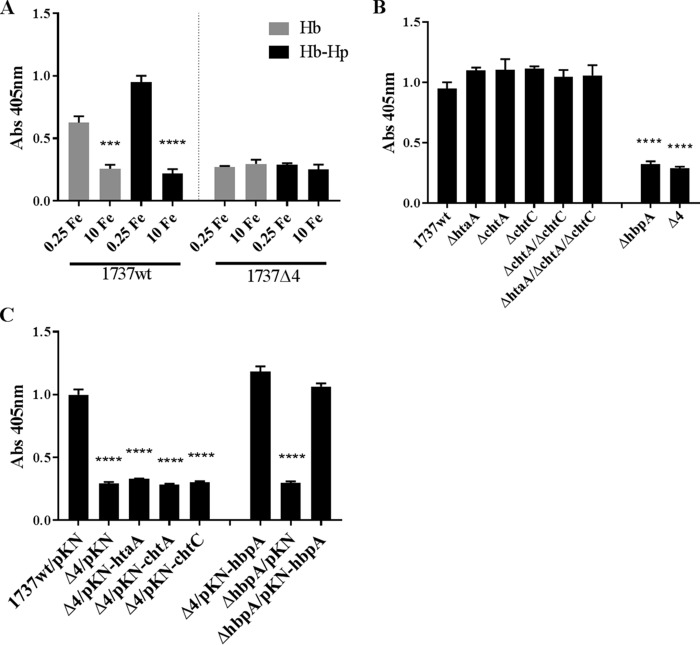

Sequence analysis of HbpA indicates that it contains an N-terminal secretion signal and a putative C-terminal transmembrane region (Fig. 5), a structural organization that is similar to those of other C. diphtheriae Hb-Hp-binding proteins, including HtaA, ChtA, and ChtC. However, unlike these other known Hb-Hp-binding proteins in C. diphtheriae, HbpA does not contain a CR domain, a region required for binding hemin, Hb, and Hb-Hp by HtaA, ChtA, and ChtC. BLAST analysis indicates that HbpA shows sequence similarity only to proteins in a limited number of C. diphtheriae strains, and a Pfam assessment indicates that HbpA does not contain any known conserved functional motifs. While the amino acid sequences required for binding to hemoproteins by HbpA are not known, HbpA does contain in its C terminus a highly charged region of unknown function that contains numerous lysine and glutamic acid residues; 41/71 amino acids in this region are charged residues (Fig. 5; indicated in bold).

FIG 5.

Predicted amino acid sequence for HbpA. The N-terminal secretion signal and C-terminal transmembrane region are underlined. Bold residues indicate a highly charged region near the C terminus.

To better understand the cellular localization and function of HbpA, we cloned the hbpA gene into an expression vector and purified the recombinant HbpA protein. Purified HbpA was used to produce polyclonal antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Protein localization studies showed that HbpA, which is expressed only under low-iron conditions, is both secreted into the extracellular medium and associated with the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 6A). We constructed a nonpolar deletion mutant of hbpA in the C. diphtheriae 1737 wild-type strain, designated 1737ΔhbpA. The deletion in 1737ΔhbpA was confirmed by the absence of HbpA in mutant strain 1737ΔhbpA grown in low-iron medium (Fig. 6B). The cloned hbpA gene on pKN-hbpA restored expression of HbpA in 1737ΔhbpA, and the recombinant HbpA protein was localized in the same cellular fractions and exhibited iron-dependent expression similar to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 6B).

FIG 6.

(A) Protein fractionation studies were done with C. diphtheriae 1737wt grown in low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) or high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) mPGT medium. Proteins present in various cellular fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, and HbpA was detected by Western blotting using anti-HbpA antibodies. Strain 1737wt carried the pKN2.6Z vector (pKN). Cell fractions are the same as those described for Fig. 1A. Purified recombinant Strep-tag-tagged HbpA is also shown (Pure HbpA). (B) Protein fractionation was done with 1737ΔhbpA carrying pKN2.6Z or pKN-hbpA grown in low- or high-iron medium. (C) Total cell lysates from 1737wt and 1737ΔhbpA that were grown in mPGT at the indicated iron levels were bound with Hb in situ. Hb binding was detected using anti-Hb antibodies. Purified HbpA is also shown. The right panel shows the Coomassie blue-stained gel of the total cell lysates and purified HbpA. (D) In situ binding with Hb-Hp was performed with the same 1737wt cell lysates and purified HbpA as those described for panel C; Hb-Hp binding was detected using anti-Hp antibodies. Experiments were repeated multiple times with similar results; a representative experiment is shown.

Whole-cell extracts from 1737ΔhbpA failed to bind Hb or Hb-Hp in situ, which confirms that HbpA is responsible for the strong binding to both hemoproteins (Fig. 6C; data not shown for Hb-Hp). Whole-cell extracts from wild-type strain 1737 grown under either low- or high-iron conditions are shown as positive controls for HbpA binding to Hb in situ (Fig. 6C). The purified recombinant HbpA protein that was electrophoresed using SDS-PAGE or native gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose was able to bind Hb and Hb-Hp in situ (Fig. 6C and D; not shown for native gels).

HbpA is involved in the utilization of Hb-Hp as an iron source.

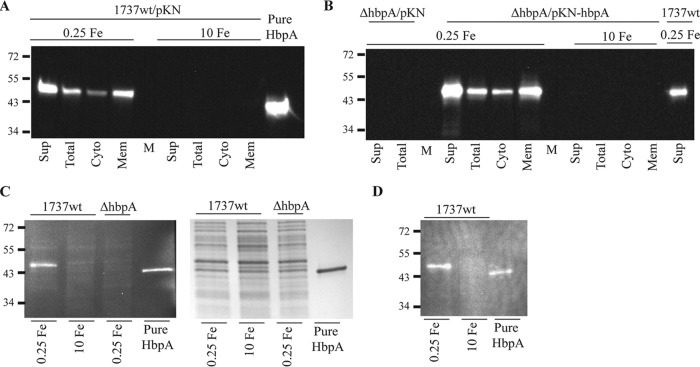

To determine if the hbpA deletion mutant, 1737ΔhbpA, was affected in its ability to utilize iron from various hemin sources, wild-type strain 1737 and 1737ΔhbpA were grown in iron-depleted medium in which either Hb, Hb-Hp, or hemin was provided as the sole iron source. Strain 1737ΔhbpA showed wild-type levels of growth when FeCl3 or hemin was used as an iron source, but the mutant exhibited significantly reduced growth relative to the wild type when Hb-Hp was used as the sole iron source (Fig. 7A). A small but statistically significant reduction in growth was observed for 1737ΔhbpA with Hb; however, the biological relevance of this decrease is unclear. These observations indicate that HbpA is involved in the acquisition of iron from Hb-Hp but is not required for the use of iron from hemin and has little if any function in the use of Hb-iron.

FIG 7.

(A) Growth assays were done with 1737wt and 1737ΔhbpA in mPGT medium containing either FeCl3 (0.25 μM), hemin (0.5 μM), Hb (4.7 μg/ml), or Hb-Hp (4.7 and 8.75 μg/ml); **, P < 0.0001; *, P < 0.02 compared to 1737wt. (B) Growth assays were done with Hb-Hp (4.7 and 8.75 μg/ml) provided as the sole iron source to the 1737 strains indicated below the graph. Vector pKN2.6Z is indicated as pKN. **, P < 0.004 compared to both 1737wt/pKN and 1737ΔhbpA/pKN-hbpA. Experiments were done at least three times; graphs show means with standard deviations.

The cloned hbpA gene on pKN-hbpA restored the ability of the hbpA mutant to use Hb-Hp as an iron source to wild-type levels of growth (Fig. 7B). Strain 1737Δ4, which carries deletions for the genes encoding all four Hb-Hp-binding proteins (HtaA, ChtA, ChtC, and HbpA), was unable to use Hb-Hp as an iron source, and the presence of the cloned hbpA gene had no effect on growth of the mutant, as expected (Fig. 7B).

We previously reported that strain 1737 with deletion of htaA showed little if any growth when Hb-Hp was the sole iron source; however, strains with mutation in either chtA or chtC showed wild-type levels of growth when Hb-Hp was used as an iron source (43). Surprisingly, a chtA chtC double mutant exhibited very poor growth in the presence of Hb-Hp, similar to the growth levels observed with the htaA mutant (43). We showed in an experiment illustrated in Fig. 7B that growth of the chtA chtC double mutant with Hb-Hp as the sole iron source can be restored to wild-type levels by either the cloned chtA or chtC gene, indicating that ChtA and ChtC have similar if not identical functions with regard to the use of Hb-Hp as an iron source. Together, these findings indicate that in C. diphtheriae strain 1737, HtaA, ChtA or ChtC (ChtA/C), and HbpA are all required for wild-type levels of growth when Hb-Hp is provided as the sole iron source.

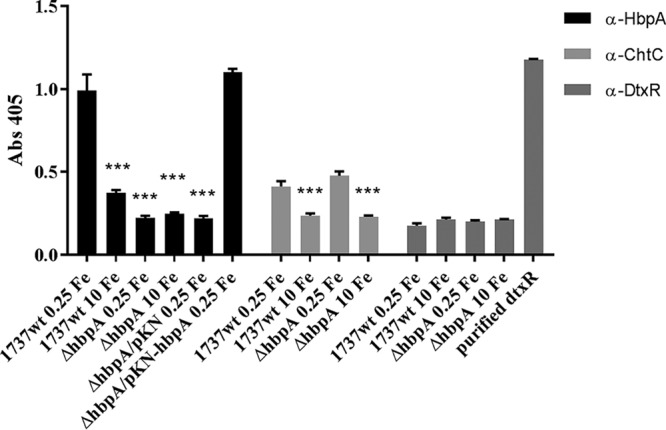

HbpA is exposed on the bacterial surface and is able to bind Hb-Hp.

Whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) studies that utilized C. diphtheriae 1737 cultures grown in either high- or low-iron medium showed that HbpA can be detected on the cell surface with antibodies directed against the HbpA protein. In the wild-type strain, HbpA was detected at significantly higher levels after growth under low-iron than high-iron conditions (Fig. 8). Only low levels were observed in the hbpA deletion mutant, and detection of HbpA was restored in 1737ΔhbpA in the presence of the cloned hbpA gene on pKN-hbpA. Control experiments using antibodies specific to ChtC or DtxR confirmed previous results (44) showing that ChtC is surface exposed and repressed under high-iron conditions, while DtxR is an intracellular protein that is not exposed on the cell surface (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Whole-cell ELISA studies indicate that HbpA is surface exposed. C. diphtheriae 1737strains were grown in either high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) or low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) mPGT medium and then transferred to a 96-well ELISA plate, where they were further incubated in PBS and processed as described in Materials and Methods. HbpA was detected using anti-HbpA antibodies. ***, P < 0.001 compared to 1737wt under low-iron conditions. ChtC and DtxR were detected with anti-ChtC and anti-DtxR antibodies, respectively. A single well on the ELISA plate was coated with purified DtxR as a control for anti-DtxR antibodies. Alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibodies were used for detection. Experiments were done at least three times; graphs show means with standard deviations.

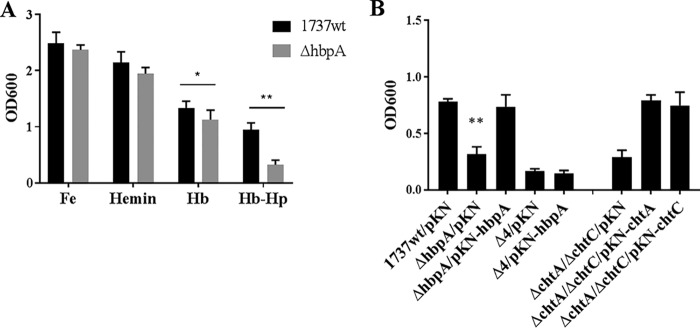

We also used whole-cell ELISAs to assess whether Hb or Hb-Hp can bind to the surface of wild-type and various mutant strains of C. diphtheriae 1737. Bacteria that were grown in high- and low-iron media were incubated with either Hb or Hb-Hp and then examined for the presence of bound hemoprotein using antibodies directed against either Hp (to detect Hb-Hp) or Hb (to detect Hb). Using the wild-type strain 1737, we showed (Fig. 9A) that Hb and Hb-Hp bind strongly to bacteria that were grown under low-iron conditions. Moreover, in the 1737Δ4 mutant, the binding of these hemoproteins to the cell surface under low-iron conditions is significantly reduced from the levels observed in the wild-type strain. The binding of Hb or Hb-Hp in high-iron medium is similar for 1737Δ4 and for the wild type.

FIG 9.

Hb and Hb-Hp bind to the surface of C. diphtheriae 1737. (A) Whole-cell ELISAs were used to assess binding of Hb and Hb-Hp to 1737wt and 1737Δ4 that were grown in either high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) or low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) mPGT medium. Cells were prepared for ELISAs as described for Fig. 8. Hb or Hb-Hp was detected with antibodies directed against Hb or Hp, respectively. Significance compared to low-iron conditions: ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) 1737 strains shown below the graph were grown in low-iron mPGT medium and tested by whole-cell ELISA for Hb-Hp binding. ****, P < 0.001 compared to 1737wt. (C) 1737wt, 1737ΔhbpA, and 1737Δ4 carrying the indicated plasmid were grown under low-iron conditions and tested for Hb-Hp binding as described above. ****, P < 0.0001 compared to 1737wt/pKN. Alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibodies were used for detection. Experiments were done at least three times; graphs show means with standard deviations.

To assess the impact of Hb-Hp binding by each of the four binding proteins whose genes are deleted in 1737Δ4, we examined the Hb-Hp binding profiles of individual mutants. We found that with deletion of htaA, chtA, or chtC, the double mutant 1737 ΔchtA/ΔchtC or the triple mutant 1737ΔhtaA/ΔchtA/ΔchtC showed wild-type levels of binding to Hb-Hp (Fig. 9B). Only 1737ΔhbpA and 1737Δ4 showed a reduction in binding to Hb-Hp. The presence of the cloned htaA, chtA, or chtC genes in 1737Δ4 did not significantly increase binding to Hb-Hp above the levels detected in 1737Δ4 carrying the vector only (Fig. 9C); however, the presence of the cloned hbpA gene restored binding to Hb-Hp to wild-type levels in 1737Δ4 and 1737ΔhbpA.

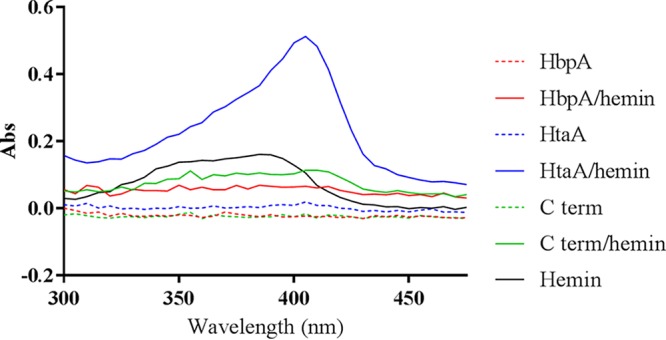

HbpA does not bind hemin.

All previously characterized Hb binding proteins in C. diphtheriae can also bind hemin (24, 44). We noted in Fig. 5 that HbpA does not harbor a CR domain, a region shown to be essential for the binding of Hb, Hb-Hp, and hemin in other hemoprotein binding proteins in C. diphtheriae. We used UV-visible spectroscopy to determine if purified HbpA is able to bind hemin. Purified HbpA in the presence of 5 μM hemin did not show a peak absorbance in the 400-nm range, a spectral region that is characteristic of hemin binding by proteins (25) (Fig. 10). The hemin-binding protein HtaA, which shows a significant increase in the 400-nm range in the presence of hemin, was used as a hemin-binding control for these studies (24). The ChtA C-terminal region (C term), which does not bind hemin (44), was used as a negative control and exhibits a spectral profile similar to that of HbpA. These findings provide strong evidence that HbpA is unable to bind hemin.

FIG 10.

UV-visible spectroscopy was used to assess hemin binding to protein. Proteins at 5 μM concentration were incubated for 20 min at room temperature with or without 5 μM hemin and then dialyzed against PBS to remove free hemin. Experiments were done multiple times; a representative experiment is shown.

DISCUSSION

The release of the Hb tetramer following lysis of erythrocytes results in the formation of the Hb dimer methemoglobin, which is rapidly, and virtually irreversibly, bound by the acute-phase serum protein Hp (48). The binding of Hb to Hp greatly reduces the toxicity of Hb and facilitates the removal of Hb from circulation through binding and uptake of the Hb-Hp complex by macrophages that contain the Hb-Hp receptor, CD163 (48, 49). The Hb-Hp complex is one of the primary host iron sources used by certain bacterial pathogens (50). While the nature of the host heme sources available to C. diphtheriae during infection is not known, it is likely that various heme compounds are used as iron sources during infection. In respiratory diphtheria, the bacteria colonize the pharyngeal mucosa and adjacent regions in the upper respiratory tract, which results in the formation of the characteristic pseudomembrane, an inflammatory necrotic lesion that appears as an adherent, fibrinous structure (2). The deleterious effects of diphtheria toxin occur at the site of colonization in the respiratory tract and at distant organs, most notably in cardiac muscle and neural tissue (4). The presence of the bacteria and the activity of the toxin result in localized inflammation, tissue destruction, and an associated serosanguinous discharge that generates an environment at the site of colonization that likely results in the accumulation of host serum proteins, including the hemoprotein Hb-Hp. In this study, we have identified HbpA as a novel iron-regulated Hb- and Hb-Hp-binding protein in C. diphtheriae that is found both anchored to the membrane and present in the extracellular medium. A C. diphtheriae mutant that carries a nonpolar deletion of the hbpA gene shows reduced ability to utilize Hb-Hp as an iron source, suggesting that HbpA functions in the utilization of hemin iron from Hb-Hp. Together with HtaA and ChtA/C, HbpA is the fourth Hb-Hp-binding protein in C. diphtheriae that is involved in the use of hemin iron from Hb-Hp.

The acquisition of hemin from Hb in Gram-positive bacteria, such as S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, is proposed to utilize a surface-anchored protein in which a unique region of the protein, such as a NEAT domain, binds to Hb, resulting in the release of hemin (37). The extracted hemin is thought to bind to a separate hemin-binding domain on the same protein, as proposed for the Shr protein in S. pyogenes and IsdB and IsdH in S. aureus (51, 52). B. anthracis utilizes the hemophores IsdX1 and IsdX2 and the cell surface receptor Hal in the utilization of Hb as an iron source (53, 54). IsdX2 is unusual in that it contains 5 NEAT domains, all of which bind Hb with various affinities, and all but the NEAT2 domain also bind hemin (55). IsdX2 is proposed to function as a secreted hemophore that binds Hb and hemin in the extracellular medium and then delivers hemin to proteins, such as IsdC, on the bacterial surface (53). However, it was shown that approximately 20% of IsdX2 is cell associated, where it may also function as a surface receptor for Hb and hemin (53, 55). The C-terminal region of IsdX2 contains a transmembrane sequence that is very similar to the putative membrane-anchoring region present in the Hb-Hp-binding proteins in C. diphtheriae (HtaA, ChtA/C, and HbpA) and to the Shr protein in S. pyogenes (56). It was not determined whether this C-terminal region in IsdX2 is responsible for anchoring the protein to the bacterial membrane.

While the use of Hb-Hp as an iron source has been described for several Gram-positive bacteria, the identification of specific proteins that are required for wild-type levels of growth when Hb-Hp is used as the sole iron source has been reported only for C. diphtheriae (43). A study that examined the role of S. aureus IsdH, a protein known to bind Hb-Hp, showed that an isdH mutant exhibited growth equivalent to that of the wild-type strain when Hb-Hp was the sole iron source (57), suggesting that either IsdH is not involved in the use of Hb-Hp or that other proteins may also be involved in the acquisition of hemin iron from Hb-Hp. While IsdB and Shr are known to bind Hb-Hp (28, 38), their involvement in the use of the hemoprotein as an iron source has not been reported; both proteins are active in the use of Hb as an iron source (23, 36). It has not been determined whether the IsdX1, IsdX2, and Hal proteins in B. anthracis can bind Hb-Hp or utilize this hemoprotein as an iron source. A recent study reported that the S. aureus IsdH and IsdB proteins can bind Hb-Hp in vitro, but only IsdH was shown to remove hemin from Hb-Hp and to inhibit binding of Hb-Hp to its cellular receptor, CD163 (28). IsdH was also shown to inhibit the uptake of Hb-Hp by CD163-expressing cells, a function that IsdB was unable to perform. The authors proposed that a function for IsdH, in addition to hemin transport, may be to limit the removal of Hb-Hp from circulation by blocking binding to CD163, which may allow higher concentrations of Hb-Hp to be available as an iron source for the pathogen (28). With regard to Gram-positive bacteria, only the C. diphtheriae HtaA, ChtA/C, and HbpA proteins are known to be involved in the use of Hb-Hp as an iron source. It has not been determined if any of these Hb-Hp-binding proteins from C. diphtheriae can inhibit binding of Hb-Hp to the CD163 receptor. In contrast to the limited studies regarding Hb-Hp iron use in Gram-positive bacteria, the use of hemin iron from Hb-Hp has been well studied in Gram-negative pathogens, including Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis (37).

While the specific mechanism utilized by C. diphtheriae strain 1737 to obtain iron from Hb-Hp is not known, it appears to require three surface components for wild-type levels of growth when Hb-Hp is the sole iron source. We showed previously that HtaA and ChtA/C are essential for growth with Hb-Hp; either a single mutation in htaA or the double mutant in chtA and chtC resulted in little if any growth when Hb-Hp was the sole iron source (43). Based on this observation, we proposed that HtaA and ChtA/C may form a complex on the surface that initially binds Hb-Hp, which is followed by removal of hemin from the hemoprotein, by an unknown mechanism, and then transfer of hemin to other hemin-binding CR domains on HtaA and/or HtaB. We also recognize that the initial steps in the use of Hb-Hp may be a sequential process; for example, rather than formation of a complex between HtaA and ChtA/C, Hb-Hp may bind initially to ChtA/C, where Hb or hemin is extracted, and then hemin or Hb (or even Hb-Hp) binds to HtaA.

In this report, we show that an hbpA mutant exhibits approximately 65% reduction in growth relative to the wild type with Hb-Hp, suggesting that HbpA facilitates or enhances the use of iron from Hb-Hp, but does not exhibit the same requirement for growth as HtaA. There are several features of HbpA that set it apart from other Hb- and Hb-Hp-binding surface proteins, including (i) the inability to bind hemin, (ii) its relatively small size (38 kDa), (iii) the lack of conserved functional motifs (such as a CR or NEAT domain) or any significant sequence homology to known proteins, and (iv) the presence of high levels of HbpA in the culture supernatant and in the membrane. The inability of HbpA to bind hemin suggests that HbpA may function early in the heme uptake process through its capacity to bind Hb-Hp. HbpA is present at approximately 2-fold-higher levels in the supernatant than the amount of HbpA associated with the cell (M. P. Schmitt and L. R. Lyman, unpublished observation). The abundance of HbpA in the extracellular environment may allow it to scavenge Hb-Hp and present it to the surface receptors HtaA and/or ChtA/C. Alternatively, HbpA may be part of a complex on the bacterial surface, where it functions with the other receptors in the binding of Hb-Hp and assists in the subsequent release of heme. A dual function for HbpA on the bacterial surface and in the supernatant is also possible, similar to the function proposed for the B. anthracis IsdX2 protein (53, 55). However, it is clear from the whole-cell binding studies that HbpA does not require the presence of the other known receptors to bind Hb-Hp on the cell surface, and it seems likely that the reason HbpA is responsible for much of the binding to Hb-Hp at the bacterial surface and in the supernatant is the abundance of the HbpA protein in both of these fractions. A model depicting the utilization of Hb-Hp as an iron source by C. diphtheriae and the possible role of HbpA and other surface proteins is shown in Fig. 11.

FIG 11.

Model of hemin uptake from Hb-Hp in C. diphtheriae strain 1737. Secreted HbpA binds to Hb-Hp in the extracellular environment, and HbpA is proposed to then facilitate the binding of Hb-Hp to surface receptors ChtA/C, HtaA, and HbpA. Alternatively, Hb-Hp may bind directly to surface receptors, bypassing the need for the secreted HbpA. Following the binding of Hb-Hp to the surface receptors, it is proposed that hemin is extracted from Hb-Hp by an unknown mechanism and transported into the cytosol by a protein relay system that may involve HtaA, HtaB, and HmuT. HmuT is a lipid-anchored hemin binding protein that is associated with the hemin ABC transporters HmuU and HmuV. Once in the cytosol, hemin is degraded by the heme oxygenase, HmuO, and the hemin-bound iron is made available for cellular metabolism.

In a previous report, we sought to determine the distribution of the htaA, chtA, and chtC genes among diverse C. diphtheriae strains (44). Our analysis included 19 strains, of which 11 strains contained all three of the genes, 1 strain lacked only chtA, and 7 strains lacked functional copies of all three genes. The complete genome sequence was known for only 14 of these strains. A phylogenetic analysis of the 14 sequenced C. diphtheriae strains indicates that strains that contain the htaA, chtA, or chtC genes show a much higher overall genetic similarity to each other than they do to strains that lack the genes (58). A review of these 19 strains revealed the presence of the hbpA gene only in those strains that also contained functional copies of htaA, chtA, and chtC. None of these four genes are genetically linked on the C. diphtheriae chromosome. Moreover, C. diphtheriae strains that were associated with a clonal group of isolates that dominated the diphtheria outbreak in the 1990s in the Former Soviet Union (FSU) also contained functional genes htaA, chtA, chtC, and hbpA (44). Table 2 shows the distribution of the hbpA genes among a diverse collection of 23 C. diphtheriae strains; the data presented show a correlation between the presence of hbpA and the presence of htaA, chtA, and chtC. While proteins involved in the acquisition of heme iron from host hemoproteins are known to be important virulence factors, additional studies are needed to determine if these C. diphtheriae Hb-Hp-binding proteins have a role in the virulence of this important human pathogen.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of HbpA and other Hb-Hp-binding proteins in C. diphtheriae strains

| Strain | Origin/description | Presence of gene(s): |

Amino acid identity (%)a | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chtA, chtC, htaA | hbpA | ||||

| 1737 | FSU/epidemic strain | + | + | 100 | 67 |

| NCTC13129 | FSU/epidemic strain | + | + | 100 | 45 |

| 1716 | FSU/epidemic strain | + | + | 100 | 67 |

| 1718 | FSU/epidemic strain | + | + | 100 | 67 |

| 1897 | FSU/epidemic strain | + | + | 100 | 67 |

| 1751 | FSU | −b | − | 67 | |

| G4193 | FSU | −b | − | 67 | |

| C7 | USA/research | − | − | 68 | |

| PW8 | USA/vaccine | − | − | 69 | |

| CDCE8392 | CDC | − | − | 8 | |

| INCA402 | Brazil | − | − | 8 | |

| BH8 | Brazil | − | − | 8 | |

| 31A | Brazil | − | − | 8 | |

| 241 | Brazil | + | + | 96 | 8 |

| HC01 | Brazil | + | + | 96 | 8 |

| HC02 | Brazil | +c | + | 54 | 8 |

| HC03 | Brazil | + | + | 54 | 8 |

| VA01 | Brazil | + | + | 44 | 8 |

| HC04 | Brazil | + | + | 44 | 8 |

| ISS4749 | Italy | + | + | 54 | 70 |

| ISS4746 | Italy | + | + | 53 | 70 |

| ISS4060 | Italy | − | − | 70 | |

Percent amino acid identity to HbpA in strain 1737.

The status of htaA is not known for strains 1751 and G4193.

The chtA gene is deleted in strain HC02.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Table 3 lists Escherichia coli and C. diphtheriae strains used in this study. Bacterial stocks were maintained in 20% glycerol at −80°C, and routine cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium for E. coli or heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) containing 0.2% Tween 80 (HIBTW) for C. diphtheriae strains. Modified PGT (mPGT) is a semidefined medium used for low-iron growth conditions for C. diphtheriae and has been previously described (59). Antibiotics were used at 50 μg/ml for kanamycin, 100 μg/ml for spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml for ampicillin, and 10 μg/ml for nalidixic acid. Antibiotics, ethylenediamine di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid) (EDDA), Tween 80, and Hp (human, Hp1-1) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., and purified Hb (human) was purchased from MP BioMedicals.

TABLE 3.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics or usea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| C. diphtheriae strains | ||

| 1737 | Wild type, Gravis biotype, tox+ | 67 |

| 1737ΔhtaA | Deletion of htaA in 1737 | 24 |

| 1737ΔchtA | Deletion of chtA in 1737 | 44 |

| 1737ΔchtC | Deletion of chtC in 1737 | 44 |

| 1737ΔchtA/ΔchtC/ΔhtaA | Deletion of chtA, chtC, and htaA in 1737 | 44 |

| 1737ΔchtA/ΔchtC | Deletion of chtA and chtC in 1737 | 44 |

| 1737ΔhbpA | Deletion of hbpA in 1737 | This study |

| 1737Δ4 | Deletion of chtA, chtC, htaA, and hbpA in 1737 | This study |

| 1737ΔdtxR | Deletion of dtxR in 1737 | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| BL21(DE3) | Protein expression | Novagen |

| DH5α | Cloning strain | Invitrogen |

| S17-1 | RP4 mobilization functions | 61 |

| EPI400 | Cloning strain | Lucigen |

| One Shot TOP10 | Cloning of PCR fragments | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET24(a)+ | Expression vector, Knr | Millipore |

| pET-hbpA | Strep-tag coding sequence-tagged hbpA cloned into pET24(a)+ | This study |

| pKN2.6Z | C. diphtheriae shuttle vector, Knr | 41 |

| pET-htaA | Strep-tag coding sequence-tagged htaA cloned into pET24(A)+ | 42 |

| pET-Cterm | Strep-tag-tagged C-terminal domain of ChtA in pET24(a)+ | 44 |

| pKN-htaA | pKN2.6Z carrying the htaA gene | 24 |

| pKN-chtC | pKN2.6Z carrying the chtC gene | 43 |

| pKN-hbpA | pKN2.6Z carrying the hbpA gene | This study |

| pK18mobsacB | C. diphtheriae shuttle vector, Knr | 62 |

| pSPZ | Promoter probe vector, Spcr | 60 |

| pSPZ-hbpA | pSPZ with hbpA promoter region | This study |

| pCR-Blunt-II-TOPO | Cloning of PCR fragments, Knr | Invitrogen |

| pMS298 | Encodes C. diphtheriae dtxR under T7 control, Ampr | 63 |

| pGP1-2 | Encodes temp-inducible T7 RNA polymerase, Knr | 71 |

Kn, kanamycin; Spc, spectinomycin; Amp, ampicillin.

Plasmid construction.

Table 3 lists the plasmids used in this study, and Table 4 lists the primers used for PCR amplification. C. diphtheriae wild-type strain 1737 was used as the source of genomic DNA for all plasmid constructs that utilized PCR unless otherwise noted. The promoter probe vector pSPZ contains a promoterless lacZ gene and was used to construct an hbpA promoter-LacZ fusion to measure expression of the hbpA promoter (60). The 377-bp intergenic region upstream of the hbpA start codon was amplified by PCR and cloned into pSPZ to construct plasmid pSPZ-hbpA. The pET-hbpA expression plasmid was constructed by ligating a PCR-derived 873-bp fragment that harbors a portion of the hbpA coding region into the vector pET24(a+). The pET-hbpA construct includes an N-terminal Strep-tag and carries deletions of the N-terminal secretion signal and the C-terminal transmembrane region of HbpA. Plasmid pKN-hbpA contains the complete coding region and the upstream promoter region for hbpA on a PCR-derived 1,436-bp fragment in vector pKN2.6Z (41).

TABLE 4.

Primers used in this study

| Primer use and name | Amplified region | Approximate size (bp) | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | |||

| RTDIP2330_1 | hbpA | 152 | CTCTCGGGTGGAGAACAAAG |

| RTDIP2330_2 | CTGCCTTGGAGTTGAGGAAG | ||

| RTDIP2329_1 | dip2329 | 226 | CTGATCCGCCAACAAGGTAT |

| RTDIP2329_2 | TGTGGATTTGGCTGTGGTTA | ||

| RTDIP2331_1 | dip2331 | 234 | ACGAACCACTGGGTGTTCTC |

| RTDIP2331_2 | CGGAAAGGATTGTCTCGGTA | ||

| RTgyrB1 | gyrB | 166 | GGTCTGACCATTACGCTGGT |

| RTgyrB2 | TCTTCTCGCGTTTCTTTGGT | ||

| RTtox1 | tox | 224 | GAACAGGCGAAAGCGTTAAG |

| RTtox2 | TTTTTGATAGGGCCATGCTC | ||

| EMSA | |||

| P2330 Fwd1 biotin | PhbpA | 377 | Biotin-CCCCCCCGTTTCCTCCGGTGAAATAATTA |

| P2330 Rev1 biotin | Biotin-CCCCCCATTCAAGATTGATTCCTTTGAGGG | ||

| P2330 Fwd2 biotin | P3′ hbpA | 175 | Biotin- CCCCCCGGCCCCTAACTGACAAATTAG |

| P2330 Rev1 biotin | Biotin-CCCCCCATTCAAGATTGATTCCTTTGAGGG | ||

| P2330 Fwd1 biotin | P5′ hbpA | 205 | Biotin-CCCCCCCGTTTCCTCCGGTGAAATAATTA |

| P2330 Rev2 biotin | Biotin-CCCCCCGCCTATTTTTCCTATATGCAAAGG | ||

| Ptox Fwd biotin | tox | 232 | Biotin-CCCCCCCTCATTGAGGAGTAGGTCCC |

| Ptox Rev biotin | Biotin-CCCCCCCATGGGCTGAAGGTGGGG | ||

| Promoter fusion | |||

| P2330 Fwd | hbpA | 377 | GCACGTCGACCGTTTCCTCCGGTGAAATAATTA |

| P2330 Rev | GATCGGATCCATTCAAGATTGATTCCTTTGAGGG | ||

| Complement clone | |||

| P2330 Fwd | hbpA pKN2.6Z | 1,436 | GCACGTCGACCGTTTCCTCCGGTGAAATAATTA |

| 2330 compl Rev | GACTGGATCCTGGGGCTTAACGCACGAAC | ||

| Expression clone | |||

| 2330 streptag Fwd | hbpA pET24(a)+ | 873 | GATCGCTAGCTGGAGCCACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAG |

| GGTGCAGCAGAAGAAGTAAAAAATGCCG | |||

| 2330 Rev | GATGAAGCTTTTATGCCTTGGAGTTGAGGAAGC | ||

| Deletion mutants | |||

| 2330 5′ KO Fwd | Up hbpA | 744 | GATGGGATCCACAAGGTATTCACGTTCTCCG |

| 2330 5′ KO Rev | GGTGGTCAGGATATTCAAGATTG | ||

| 2330 3′ KO Fwd | Down hbpA | 762 | CAATCTTGAATATCCTGACCACCCATTTGTTC |

| GTGCGTTAAGCC | |||

| 2330 3′ KO Rev | GTTCGTCGACGTTGACTAGGAGGCCTTCG |

Restriction sites are underlined, and the Strep-tag sequence is indicated in bold type.

Deletion mutant construction.

A nonpolar allelic replacement technique previously described (61) was used to create a deletion mutant of hbpA in C. diphtheriae 1737. The 5′ and 3′ ends of the hbpA gene, including regions upstream and downstream of the coding region, were amplified by PCR, purified by gel extraction, and then used as a template in a second PCR, which resulted in a single DNA fragment containing the deleted region. This fragment was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, ligated into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and then excised from the TOPO vector and ligated into pK18mobsacB (62). The pK18mobsacB vector contains an origin of replication that functions in E. coli but not in C. diphtheriae. The resulting pK18mobsacBΔhbpA plasmid was transformed into E. coli S17-1 and then mated into C. diphtheriae 1737 wild-type and 1737ΔhtaA/ΔchtA/ΔchtC strains. The deletion of hbpA in the 1737 strains was confirmed by PCR. Deletion of the dtxR gene in 1737 was done using the same procedure and plasmid constructs as those previously used to make the dtxR deletion in strain C7 (47).

Protein analysis and antibody production.

Purification of DtxR was performed as described previously with modifications (44, 63). C. diphtheriae DtxR was purified using the two-plasmid system in E. coli DH5α. An overnight culture grown at 30°C with appropriate antibiotics was diluted into fresh LB medium and grown to mid-logarithmic growth phase. Expression of DtxR was induced by heat shock at 42°C for 30 min and growth at 37°C for 3 h. Bacterial cells were pelleted, resuspended in lysis buffer (42 mM NaH2PO4, 58 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and lysed by sonication. Following sonication, cell debris was removed through centrifugation, and the clarified lysate was run through nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA)–agarose (Qiagen). The Ni-NTA–agarose was washed using lysis buffer, and protein was eluted using elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Fractions containing DtxR were dialyzed twice against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and once against PBS with 15% glycerol. Protein samples were stored at −20°C prior to use.

E. coli strain BL21(DE3) was used to express recombinant Strep-tagged HbpA using a previously described method (42) with the following modifications. Isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction was done at 27°C, and the bacteria were lysed using the FastPrep cell lysis system (MP Biomedical) (64) followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C. Lysis was done in buffer W (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl) as recommended by the manufacturer for purification of Strep-tag-tagged proteins. Strep-tag-tagged HbpA present in the cell extract was purified using a Strep-Tactin Sepharose column (IBA Life Sciences) as per the manufacturer's instructions and eluted in buffer E (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM desthiobiotin). The HbpA protein recovered after elution from the column was dialyzed against PBS and then against PBS with 20% glycerol and stored at −20°C. The purified HbpA protein was used to generate antibodies in guinea pigs using standard methods (Cocalico Biologicals, Inc.). For cell fractionation analyses, cell lysates were prepared with the FastPrep system as described above, with the exception that lysis was done in PBS. Following lysis (total protein), 500-μl samples were centrifuged for 90 min at 65,000 rpm in a Beckman Optima TLX ultracentrifuge at 4°C. The supernatant contains cytosolic proteins, while the pellet, which was resuspended in 100 μl of PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBST), contains the membrane fraction.

Proteins that were stained with Coomassie blue and excised from SDS-PAGE gels were identified using LC-MS/MS analysis, which was performed by the FDA/CBER core facility.

Heme iron utilization assays.

Iron utilization was assessed using a growth assay as previously described (43). Briefly, C. diphtheriae strains were grown overnight at 37°C in HIBTW and then diluted 1:2 with HIBTW and incubated for 1 to 2 h. Following the incubation, 500 μl of culture was centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml mPGT containing 1 μM FeCl3 and grown for 4 to 6 h at 37°C until the cultures had reached log phase. The log-phase cultures were used to inoculate fresh mPGT medium that contained FeCl3 (at 0.25 or 10 μM), hemin (0.5 μM), Hb (4.7 μg/ml), or Hb-Hp (prebound at room temperature for 30 min with Hb at 4.7 μg/ml and Hp at 8.75 μg/ml) to a predicted optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.03. After 16 to 18 h of growth, the OD600 was measured. GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis of growth.

Beta-galactosidase assays.

C. diphtheriae strains containing the pSPZ-promoter fusion constructs were incubated as described above for the iron utilization assays. The final overnight cultures were grown in 0.25 or 10 μM FeCl3 in mPGT, following which LacZ activity was assessed as previously described (44). Assays to assess the impact of Hb on hbpA promoter activity were done in HIBTW medium. The final overnight cultures in HIBTW contained either no added supplements, Hb at 325 μg/ml, EDDA at 18 μg/ml, or both Hb and EDDA.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

For Western blot analysis, cell lysates or purified proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (65) and stained with Bio-Safe Coomassie blue (Bio-Rad) or transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a semidry transfer cell (24). Western blot procedures were performed as described previously (24). Anti-HbpA (Cocalico Biologics, Inc.), anti-Hb, and anti-Hp (Sigma Chemical Co.) antibodies were used at a 1:10,000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (Sigma) were used at 1:50,000 to detect binding of the primary antibody per established procedures (24).

For the in situ binding study to identify proteins that bind Hb or Hb-Hp, the Western blot procedure was modified as follows: after nitrocellulose membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) with 5% blotting grade blocking powder (Bio-Rad), an additional incubation step was done in Hb (10.1 μg/ml in TBS-T) or Hb-Hp (prebound for 30 min at room temperature with Hb at 10.1 μg/ml and Hp at 8.75 μg/ml in TBS-T) for 1 h at 37°C. Following the 1-h incubation, membranes were washed three times with TBS-T for 5 to 15 min before proceeding with the primary antibody step.

The following procedure was used to assess HbpA binding to Hb-Hp under nondenaturing conditions: Tris-glycine gels with 10% acrylamide-bis (30% solution, 29:1; Bio-Rad) were hand cast and used with native sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and 1× Tris-glycine running buffer to separate proteins. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described above for in situ binding analysis. HbpA was not subjected to boiling or high temperatures, reducing conditions, or any detergents such as SDS during this procedure.

Identification of surface proteins and hemoprotein binding studies using whole cells.

To verify the surface exposure of various proteins and to assess binding of Hb-Hp, a whole-cell ELISA was used. A previously described protocol was followed to determine surface exposure of proteins in whole cells (44). Briefly, bacterial cultures were grown to stationary phase under low-iron (0.25 μM FeCl3) or high-iron (10 μM FeCl3) conditions in mPGT medium. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS, and then incubated overnight at 37°C in microtiter plates. The plates were then washed, followed by incubation with blocking buffer (5% blotting grade blocking powder [Bio-Rad] in PBST). The bacteria were then incubated with protein-specific primary antibodies, followed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-linked secondary antibodies. All antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer, and all incubation steps were done at 37°C for 1 h. Substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP; Sigma Chemical Co.) was used to develop the signal, which was read at 405 nm on a Multiskan FC from Thermo Scientific.

To assess Hb-Hp binding to cell surface proteins, a similar ELISA protocol was followed. Microtiter plates were coated with bacterial cultures and blocked as described above. Following the blocking step, the plates were incubated with Hb-Hp (prebound for 30 min at room temperature with Hb at 10.1 and Hp at 8.75 μg/ml in PBST) for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation with Hb-Hp, an additional set of three washes in PBST were done, and the assay proceeded as described above for the whole-cell ELISA. Anti-haptoglobin antibodies were used to detect Hb-Hp bound to the cells' surface.

UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Purified Strep-tag-tagged HbpA was analyzed for hemin binding by UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy using a Genesys 10S UV-Vis system from Thermo Scientific. Purified Strep-tag-tagged HtaA (42) was used as a positive control, and the purified Strep-tag-tagged C-terminal domain of ChtA (C term) (44) was used as a negative binding control. Proteins at 5 μM in PBS buffer with 20% glycerol were incubated at room temperature with 5 μM hemin for 20 min, dialyzed three times against PBS to remove free hemin, and then analyzed by UV-visible absorption scan using wavelengths from 200 to 600 nm. Baseline absorbance was established using samples containing only PBS buffer.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Purified DtxR was incubated at room temperature for 15 min with biotinylated DNA fragments in DtxR binding buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05 μg/μl sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 0.5 mM FeSO4, and 10% glycerol [pH 7.0]). Samples were separated by gel electrophoresis in 5% acrylamide with 20 mM Na2HPO4 and 1 mM DTT, pH 7.0, at 4°C for 70 min. Following gel electrophoresis, transfer of samples was done at 4°C onto a nylon membrane (Invitrogen) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE; Bio-Rad). Biotinylated DNA fragments were detected by the LightShift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Thermo Scientific).

RNA isolation and qPCR.

Wild-type C. diphtheriae was grown to mid-logarithmic phase in mPGT with either 0.25 or 10 μM FeCl3; 95% ethanol and 5% phenol were added at a 1:10 dilution to cells prior to centrifugation. Following centrifugation, cells were suspended in PBS with 5% ethanol, 0.5% phenol, and 14.3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were lysed in Matrix B (MP Biomedicals); 750 μl of TRIzol LS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the lysate, and samples were briefly vortexed and then centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min to remove cell debris. Approximately 700 μl of supernatant was collected and processed according to the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit instructions (Zymo Research). Total RNA was treated using the Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion). The ProtoScript II first strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England BioLabs, Inc.) was used to generate cDNA, and the Luna Universal qPCR master mix (New England BioLabs, Inc.) was used for detection. Primers were designed using Primer 3 (66). Data were collected by a LightCycler 96 system (Roche) and analyzed using the ΔΔCq method (where Cq is quantification cycle). Normalization of Cq values was done against gyrB.

RACE assays.

Total RNA isolated from wild-type C. diphtheriae strain 1737 grown under iron-limited conditions was subjected to Ambion Turbo DNase I treatment (Invitrogen). An hbpA-specific primer (DIP2330_GSP1, TGG TGC ATG GAG GAA TTT TTG G) was used to prime reverse transcription from the total RNA following directions using the 5′ RACE system for rapid amplification of cDNA ends, version 2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific). A poly(C) tail was added to the product and used to prime PCR in conjunction with a second hbpA-specific primer (DIP2330_GSP2, TGA TGA CTA ATC CAT CCC CAT AC). The product was purified using the Geneclean kit (MP Biomedicals) and submitted for sequencing (Macrogen).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the intramural research program at the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration.

We thank Scott Stibitz and Paul Carlson for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zasada AA. 2015. Corynebacterium diphtheriae infections currently and in the past. Przegl Epidemiol 69:439–444, 569–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadfield TL, McEvoy P, Polotsky Y, Tzinserling VA, Yakovlev AA. 2000. The pathology of diphtheria. J Infect Dis 181(Suppl 1):S116–S120. doi: 10.1086/315551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collier RJ. 2001. Understanding the mode of action of diphtheria toxin: a perspective on progress during the 20th century. Toxicon 39:1793–1803. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes RK. 2000. Biology and molecular epidemiology of diphtheria toxin and the tox gene. J Infect Dis 181(Suppl 1):S156–S167. doi: 10.1086/315554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd J, Oza MN, Murphy JR. 1990. Molecular cloning and DNA sequence analysis of a diphtheria tox iron-dependent regulatory element (dtxR) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:5968–5972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitt MP, Holmes RK. 1991. Iron-dependent regulation of diphtheria toxin and siderophore expression by the cloned Corynebacterium diphtheriae repressor gene dtxR in C. diphtheriae C7 strains. Infect Immun 59:1899–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunkle CA, Schmitt MP. 2003. Analysis of the Corynebacterium diphtheriae DtxR regulon: identification of a putative siderophore synthesis and transport system that is similar to the Yersinia high-pathogenicity island-encoded yersiniabactin synthesis and uptake system. J Bacteriol 185:6826–6840. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.23.6826-6840.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trost E, Blom J, de Castro Soares S, Huang IH, Al-Dilaimi A, Schroder J, Jaenicke S, Dorella FA, Rocha FS, Miyoshi A, Azevedo V, Schneider MP, Silva A, Camello TC, Sabbadini PS, Santos CS, Santos LS, Hirata R Jr, Mattos-Guaraldi AL, Efstratiou A, Schmitt MP, Ton-That H, Tauch A. 2012. Pangenomic study of Corynebacterium diphtheriae that provides insights into the genomic diversity of pathogenic isolates from cases of classical diphtheria, endocarditis, and pneumonia. J Bacteriol 194:3199–3215. doi: 10.1128/JB.00183-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. 2008. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778:1781–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skaar EP. 2010. The battle for iron between bacterial pathogens and their vertebrate hosts. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheldon JR, Laakso HA, Heinrichs DE. 2016. Iron acquisition strategies of bacterial pathogens. Microbiol Spectr 4(2). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0010-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choby JE, Skaar EP. 2016. Heme synthesis and acquisition in bacterial pathogens. J Mol Biol 428:3408–3428. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otto BR, Verweij-van Vught AM, MacLaren DM. 1992. Transferrins and heme-compounds as iron sources for pathogenic bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol 18:217–233. doi: 10.3109/10408419209114559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgenthau A, Pogoutse A, Adamiak P, Moraes TF, Schryvers AB. 2013. Bacterial receptors for host transferrin and lactoferrin: molecular mechanisms and role in host-microbe interactions. Future Microbiol 8:1575–1585. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM (ed). 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammer ND, Skaar EP. 2011. Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus iron acquisition. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:129–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyckoff EE, Mey AR, Payne SM. 2007. Iron acquisition in Vibrio cholerae. Biometals 20:405–416. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai PJ, Nzeribe R, Genco CA. 1995. Binding and accumulation of hemin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun 63:4634–4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stojiljkovic I, Hantke K. 1994. Transport of haemin across the cytoplasmic membrane through a haemin-specific periplasmic binding-protein-dependent transport system in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol 13:719–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson DP, Payne SM. 1994. Characterization of the Vibrio cholerae outer membrane heme transport protein HutA: sequence of the gene, regulation of expression, and homology to the family of TonB-dependent proteins. J Bacteriol 176:3269–3277. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3269-3277.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cescau S, Cwerman H, Letoffe S, Delepelaire P, Wandersman C, Biville F. 2007. Heme acquisition by hemophores. Biometals 20:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troxell B, Hassan HM. 2013. Transcriptional regulation by ferric uptake regulator (Fur) in pathogenic bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:59. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouattara M, Cunha EB, Li X, Huang YS, Dixon D, Eichenbaum Z. 2010. Shr of group A Streptococcus is a new type of composite NEAT protein involved in sequestering haem from methaemoglobin. Mol Microbiol 78:739–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen CE, Schmitt MP. 2009. HtaA is an iron-regulated hemin binding protein involved in the utilization of heme iron in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Bacteriol 191:2638–2648. doi: 10.1128/JB.01784-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazmanian SK, Skaar EP, Gaspar AH, Humayun M, Gornicki P, Jelenska J, Joachmiak A, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. 2003. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 299:906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1081147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilpa RM, Robson SA, Villareal VA, Wong ML, Phillips M, Clubb RT. 2009. Functionally distinct NEAT (NEAr Transporter) domains within the Staphylococcus aureus IsdH/HarA protein extract heme from methemoglobin. J Biol Chem 284:1166–1176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu H, Xie G, Liu M, Olson JS, Fabian M, Dooley DM, Lei B. 2008. Pathway for heme uptake from human methemoglobin by the iron-regulated surface determinants system of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 283:18450–18460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801466200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saederup KL, Stodkilde K, Graversen JH, Dickson CF, Etzerodt A, Hansen SW, Fago A, Gell D, Andersen CB, Moestrup SK. 2016. The Staphylococcus aureus protein IsdH inhibits host hemoglobin scavenging to promote heme acquisition by the pathogen. J Biol Chem 291:23989–23998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.755934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiedemann MT, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. 2012. Multiprotein heme shuttle pathway in Staphylococcus aureus: iron-regulated surface determinant cog-wheel kinetics. J Am Chem Soc 134:16578–16585. doi: 10.1021/ja305115y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muryoi N, Tiedemann MT, Pluym M, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. 2008. Demonstration of the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) heme transfer pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 283:28125–28136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802171200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grigg JC, Vermeiren CL, Heinrichs DE, Murphy ME. 2007. Haem recognition by a Staphylococcus aureus NEAT domain. Mol Microbiol 63:139–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skaar EP, Gaspar AH, Schneewind O. 2004. IsdG and IsdI, heme-degrading enzymes in the cytoplasm of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 279:436–443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazmanian SK, Liu G, Ton-That H, Schneewind O. 1999. Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science 285:760–763. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fonner BA, Tripet BP, Eilers BJ, Stanisich J, Sullivan-Springhetti RK, Moore R, Liu M, Lei B, Copie V. 2014. Solution structure and molecular determinants of hemoglobin binding of the first NEAT domain of IsdB in Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry 53:3922–3933. doi: 10.1021/bi5005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres VJ, Pishchany G, Humayun M, Schneewind O, Skaar EP. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus IsdB is a hemoglobin receptor required for heme iron utilization. J Bacteriol 188:8421–8429. doi: 10.1128/JB.01335-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pishchany G, Sheldon JR, Dickson CF, Alam MT, Read TD, Gell DA, Heinrichs DE, Skaar EP. 2014. IsdB-dependent hemoglobin binding is required for acquisition of heme by Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 209:1764–1772. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheldon JR, Heinrichs DE. 2015. Recent developments in understanding the iron acquisition strategies of Gram positive pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39:592–630. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates CS, Montanez GE, Woods CR, Vincent RM, Eichenbaum Z. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes operon involved in binding of hemoproteins and acquisition of iron. Infect Immun 71:1042–1055. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1042-1055.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu H, Liu M, Lei B. 2008. The surface protein Shr of Streptococcus pyogenes binds heme and transfers it to the streptococcal heme-binding protein Shp. BMC Microbiol 8:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher M, Huang YS, Li X, McIver KS, Toukoki C, Eichenbaum Z. 2008. Shr is a broad-spectrum surface receptor that contributes to adherence and virulence in group A Streptococcus. Infect Immun 76:5006–5015. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00300-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drazek ES, Hammack CA, Schmitt MP. 2000. Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from haemin and haemoglobin are homologous to ABC haemin transporters. Mol Microbiol 36:68–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen CE, Schmitt MP. 2011. Novel hemin binding domains in the Corynebacterium diphtheriae HtaA protein interact with hemoglobin and are critical for heme iron utilization by HtaA. J Bacteriol 193:5374–5385. doi: 10.1128/JB.05508-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen CE, Schmitt MP. 2015. Utilization of host iron sources by Corynebacterium diphtheriae: multiple hemoglobin-binding proteins are essential for the use of iron from the hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex. J Bacteriol 197:553–562. doi: 10.1128/JB.02413-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen CE, Burgos JM, Schmitt MP. 2013. Analysis of novel iron-regulated, surface-anchored hemin-binding proteins in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Bacteriol 195:2852–2863. doi: 10.1128/JB.00244-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Efstratiou A, Dover LG, Holden MT, Pallen M, Bentley SD, Besra GS, Churcher C, James KD, De Zoysa A, Chillingworth T, Cronin A, Dowd L, Feltwell T, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Moule S, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Rutherford KM, Thomson NR, Unwin L, Whitehead S, Barrell BG, Parkhill J. 2003. The complete genome sequence and analysis of Corynebacterium diphtheriae NCTC13129. Nucleic Acids Res 31:6516–6523. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bibb LA, King ND, Kunkle CA, Schmitt MP. 2005. Analysis of a heme-dependent signal transduction system in Corynebacterium diphtheriae: deletion of the chrAS genes results in heme sensitivity and diminished heme-dependent activation of the hmuO promoter. Infect Immun 73:7406–7412. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7406-7412.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bibb LA, Schmitt MP. 2010. The ABC transporter HrtAB confers resistance to hemin toxicity and is regulated in a hemin-dependent manner by the ChrAS two-component system in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Bacteriol 192:4606–4617. doi: 10.1128/JB.00525-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen CB, Torvund-Jensen M, Nielsen MJ, de Oliveira CL, Hersleth HP, Andersen NH, Pedersen JS, Andersen GR, Moestrup SK. 2012. Structure of the haptoglobin-haemoglobin complex. Nature 489:456–459. doi: 10.1038/nature11369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kristiansen M, Graversen JH, Jacobsen C, Sonne O, Hoffman HJ, Law SK, Moestrup SK. 2001. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature 409:198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohde KH, Dyer DW. 2004. Analysis of haptoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin interactions with the Neisseria meningitidis TonB-dependent receptor HpuAB by flow cytometry. Infect Immun 72:2494–2506. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2494-2506.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spirig T, Malmirchegini GR, Zhang J, Robson SA, Sjodt M, Liu M, Krishna Kumar K, Dickson CF, Gell DA, Lei B, Loo JA, Clubb RT. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus uses a novel multidomain receptor to break apart human hemoglobin and steal its heme. J Biol Chem 288:1065–1078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ouattara M, Pennati A, Devlin DJ, Huang YS, Gadda G, Eichenbaum Z. 2013. Kinetics of heme transfer by the Shr NEAT domains of Group A Streptococcus. Arch Biochem Biophys 538:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maresso AW, Garufi G, Schneewind O. 2008. Bacillus anthracis secretes proteins that mediate heme acquisition from hemoglobin. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000132. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balderas MA, Nobles CL, Honsa ES, Alicki ER, Maresso AW. 2012. Hal is a Bacillus anthracis heme acquisition protein. J Bacteriol 194:5513–5521. doi: 10.1128/JB.00685-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Honsa ES, Maresso AW. 2011. Mechanisms of iron import in anthrax. Biometals 24:533–545. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]