Abstract

Background

The media has devoted significant attention to anecdotes of individuals who post messages on Facebook prior to suicide. However, it is unclear to what extent social media is perceived as a source of help or how it compares to other sources of potential support for mental health problems.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the degree to which military veterans with depression use social media for help-seeking in comparison to other more traditional sources of help.

Methods

Cross-sectional self-report survey of 270 adult military veterans with probable major depression. Help-seeking intentions were measured with a modified General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Facebook users and nonusers were compared via t tests, Chi-square, and mixed effects regression models. Associations between types of help-seeking were examined using mixed effects models.

Results

The majority of participants were users of social media, primarily Facebook (n=162). Mean overall help-seeking intentions were similar between Facebook users and nonusers, even after adjustment for potential confounders. Facebook users were very unlikely to turn to Facebook as a venue for support when experiencing either emotional problems or suicidal thoughts. Compared to help-seeking intentions for Facebook, help-seeking intentions for formal (eg, psychologists), informal (eg, friends), or phone helpline sources of support were significantly higher. Results did not substantially change when examining users of other social media, women, or younger adults.

Conclusions

In its current form, the social media platform Facebook is not seen as a venue to seek help for emotional problems or suicidality among veterans with major depression in the United States.

Keywords: social media, social networking sites, internet, Facebook, service use, utilization, treatment-seeking

Introduction

Social media has become an integral part of people’s daily lives, including military veterans. As of 2016, there were 1.89 billion active users on Facebook [1], with 76% logging on daily and spending 50 minutes on average on the site [2,3]. All told, an estimated 1 out of every 7 minutes spent online is spent on Facebook [4]. In 2014, Facebook reported that 4 million of its users were US active duty members or military veterans [5], and a 2012 online survey on personal technology use among military service members found that more than three-quarters of them used social networking sites, predominantly Facebook [6].

Facebook is most commonly used for purposes such as entertainment, communicating with friends and family, and keeping up with news and current events, with 31% to 47% of users citing such reasons [7]. However, there are also ways Facebook appears to be used that may be relevant to obtaining emotional support or help for mental health concerns. For instance, 30% of Facebook users cite learning about ways to help others as a reason for their Facebook use, and 23% note receiving support from network members as another reason [7]. Among veterans, US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) patients appear to use social media to find others with similar health problems at about the same rate as nonveterans [8].

Social media may be a valuable venue for help-seeking for several reasons. It is a highly accessible resource, and use of internet-based sources of help for health issues is common [9]. Researchers have been interested in the potential to use social media to reach, recruit, identify, engage, support, or treat individuals at risk for mental health problems [10-15]. Individuals coping with mental illness are active on social media [16], and Facebook is used as a place to share feelings [17] and mobilize social support [18], particularly advice and practical help [19]. Occasionally, it is even used as a forum to disclose suicidal thoughts [20]. Facebook, for its part, has collaborated with suicide prevention organizations to develop tools to identify and intervene on behalf of individuals who appear to be at risk for self-harm or suicide [21].

The importance of novel approaches to enhance help-seeking is accentuated by the fact that rates of help-seeking are generally low in proportion to the number of people suffering from psychiatric problems such as depression [22] and even recent suicidal ideation [23]. A similar pattern is seen among military service members and veterans, who are also thought to underuse mental health services or be underserved [24-26]. The need to address this gap between suffering and help-seeking is likely to grow given evidence of rising suicide rates and the list-topping proportion of the global burden of disease attributable to mental illnesses [27,28]. However, it is unclear to what extent social media actually serves as an existing source of help-seeking, particularly for mental health problems and particularly beyond the adolescent and young adult population [29,30].

Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the degree to which veterans with depression use social media for help-seeking in comparison to other more traditional sources of help.

Methods

Recruitment

We drew participants from a larger study of 301 primary care patients at a VA hospital and its satellite clinics who had symptoms of major depression and reported having at least one close relationship. Patients were excluded if they had severe hearing impairment or recently active major psychiatric comorbidities (bipolar disorder, psychosis, or neurocognitive disorder). Due to the low percentage of women veterans, we oversampled women to increase diversity of our sample. Potentially eligible veterans were first screened for depression via a phone-administered 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) followed by an in-person visit if eligible and interested. Those eligible for inclusion in this study were the 270 individuals who had a PHQ-8 score ≥9, who were then administered a set of survey items about social media use. Meta-analyses have found that a cutoff score of 9 on the PHQ-9 is one of the optimal choices for diagnosing major depression in primary care settings [31]; the identical cutpoint should be used on the PHQ-8 due to its high level of correlation with PHQ-9 score [32].

Measures

Help-Seeking

We administered the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ), an adaptable self-report measure that assesses intention to seek help if experiencing an emotional problem or suicidal thoughts. Multiple possible sources of help are presented, and response options for each range from 1=extremely unlikely to 7=extremely likely. Because original items were developed in Australia, we slightly modified them for an American context and added Facebook as another potential source of help. Participants were asked about help-seeking on Facebook generally, without specifying particular areas or functions within Facebook (eg, support groups or interest pages). We sorted sources into 4 categories: (1) Facebook help-seeking; (2) informal help-seeking, which is drawn from members of one’s social network such as friends and family; (3) phone helpline help-seeking, which cited the Veteran’s Crisis Line as an example; and (4) formal help-seeking, which included a mental health professional or primary care provider. For categories with multiple items, we averaged participant responses to each source. The GHSQ has strong reliability and validity [33], particularly when used in multi-item form as we did [34].

Social Media Use

We used a series of survey items adapted from questions used by the Pew Research Center [35,36] to assess social media use. First, we assessed whether veterans were social media users (“Do you ever use the internet or a mobile app to use Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr, or Facebook?”). Next, we assessed frequency of use of the same social media platforms. Finally, we assessed frequency of active social media use (sharing, posting, or commenting) because prior research has indicated that social media use is often characterized by passive consumption of information (eg, scrolling through news feeds), a behavior linked to worsened emotional well-being [37].

Covariates

We assessed additional sociodemographic and clinical characteristics including age, gender, minority status, education level, rurality of residence, stability of housing, financial hardship, history of suicide attempt, alcohol misuse, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, depression symptoms, and offline social contact. See Multimedia Appendix 1 for additional details.

Statistical Analysis

We first examined missingness of data; all survey items had less than 2% missing data. We used mean imputation for missing responses to GHSQ items that were part of informal or formal help-seeking. We summarized key variables using descriptive statistics. We analyzed sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants who were Facebook users and nonusers using 2-sample t tests and Pearson Chi-square tests. To compare help-seeking intentions from different GHSQ source categories, we used multilevel mixed-effects linear regressions. We performed subgroup analyses to determine whether the pattern of help-seeking intentions differed when the sample was restricted to various groups of participants, including frequent Facebook users (defined as visiting at least daily), active Facebook users (defined as sharing, posting, or commenting on Facebook at least daily), and users of social media platforms other than Facebook. Analyses were performed using Stata versions 14.2 and 15.0 (StataCorp LLC), and 2-sided statistical significance was defined as P<.05.

Results

Descriptive Data

In terms of help-seeking intentions, 58.1% (157/270) endorsed having at least 1 source they intended to use (GHSQ score of 5 or more) if experiencing an emotional problem. If having suicidal thoughts, 55.6% (150/270) endorsed having at least 1 help-seeking source.

Of our 270 participants, 162 (60.0%) were Facebook users, 106 (39.3%) used Facebook at least daily, and 65 (24.1%) used Facebook actively (as opposed to passively) at least daily. Use of any social media platform other than Facebook was uncommon (49/270, 18.1%), with use of individual platforms (eg, Twitter) even more rare. Compared to nonusers, Facebook users were younger and used other social media and more likely to be women, live in urban areas, and be at risk for misusing alcohol; they were less likely to have a history of a suicide attempt (Table 1). However, mean help-seeking intentions for each source of help did not differ significantly between Facebook users and nonusers. This was true for both help-seeking for emotional problems and suicidal thoughts. Results also remained consistent after adjustment for potential confounders (age, gender, urbanicity, alcohol use, use of social media sites other than Facebook, and history of suicide attempt). All remaining results are based on data from only participants who were Facebook users.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with active depressive symptoms.

| Characteristic | Facebook users (n=162) | Facebook nonusers (n=108) | P value | |||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 52 (14) | 61 (13) | <.001 | |||||

| Under 40, n (%) | 37 (22.8) | 11 (10.2) | ||||||

| 40-49, n (%) | 29 (17.9) | 8 (7.4) | ||||||

| 50-59, n (%) | 40 (24.7) | 20 (18.5) | ||||||

| 60 or over, n (%) | 56 (34.6) | 69 (63.9) | ||||||

| Male, n (%) | 134 (82.7) | 99 (91.7) | .04 | |||||

| Racial or ethnic minority, n (%) | 37 (22.8) | 26 (24.1) | .81 | |||||

| Education, n (%) | .55 | |||||||

| High school or less | 20 (12.3) | 20 (18.5) | ||||||

| Some college | 59 (36.4) | 39 (36.1) | ||||||

| Two-year degree | 43 (26.5) | 25 (23.1) | ||||||

| Four-year degree or more | 40 (24.7) | 24 (22.2) | ||||||

| Rural residence, n (%) | 22 (13.6) | 25 (23.1) | .04 | |||||

| Stable housing, n (%) | 149 (91.2) | 98 (90.7) | .72 | |||||

| Financial hardship, n (%) | 44 (27.2) | 28 (25.9) | .97 | |||||

| History of suicide attempt, n (%) | 19 (11.7) | 29 (26.9) | .001 | |||||

| Alcohol misusea, n (%) | 65 (40.1) | 27 (25.0) | .01 | |||||

| PTSD symptomsb, n (%) | 108 (66.6) | 67 (62.0) | .44 | |||||

| PHQ-9 scorec, n (%) | 15 (9.3) | 15 (13.9) | .77 | |||||

| Use social media besides Facebookd, n (%) | 42 (25.9) | 7 (6..5) | <.001 | |||||

| Offline social contacte, n (%) | .57 | |||||||

| Every few months or less | 15 (9.3) | 7 (6.5) | ||||||

| Once or twice a month | 35 (21.6) | 18 (16.7) | ||||||

| Weekly to a few times a week | 79 (48.8) | 57 (52.8) | ||||||

| Daily or more | 33 (20.4) | 26 (24.1) | ||||||

aAlcohol misuse was operationalized as an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score ≥4 in men (≥3 in women).

bPosttraumatic stress disorder was operationalized as a Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist score ≥3.

cNine-item Patient Health Questionnaire score represents severity of symptoms of major depression.

dParticipants were asked whether they ever use Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr, or Twitter.

eAverage frequency of in-person social contact with up to 3 individuals nominated as close relations.

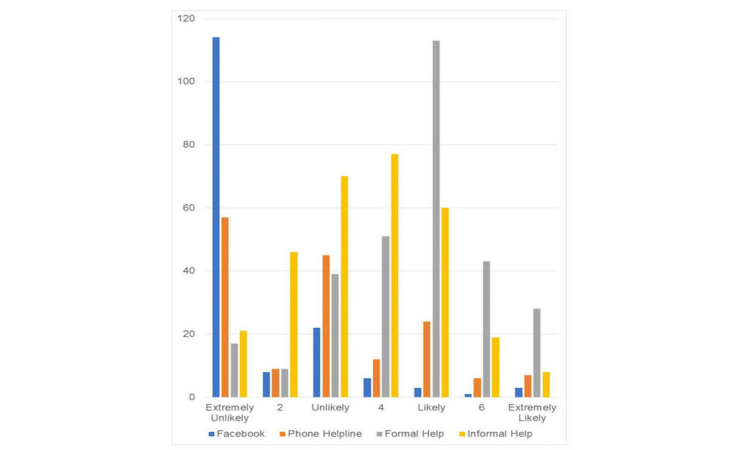

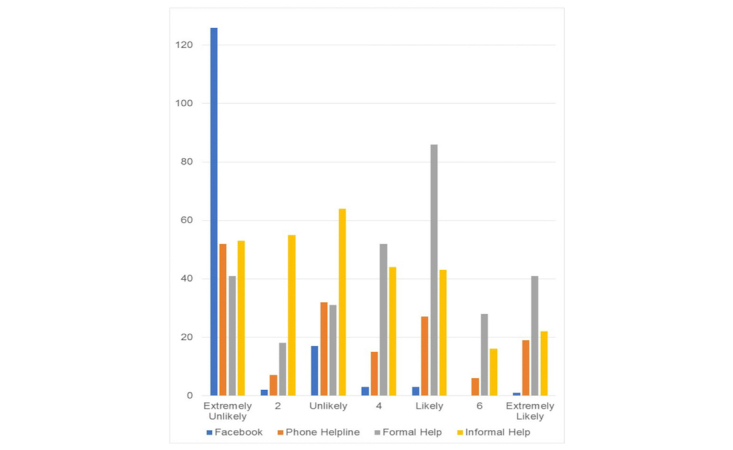

A total of 58.6% (95/162) of Facebook users endorsed having at least 1 help-seeking source for emotional problems; for suicidal thoughts, 50.6% (82/162) intended to use at least 1 source of help. The mean help-seeking intention for emotional problems via Facebook was 1.67 (95% CI 1.46 to 1.87) on a scale ranging from 1=extremely unlikely to 7=extremely likely. Help-seeking intention for suicidal thoughts via Facebook was similarly low (mean 1.41, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.58). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the preponderance of participants who were extremely unlikely to seek help from Facebook as opposed to a more even distribution of likelihood to seek help from other sources.

Figure 1.

Frequency of help-seeking intentions if experiencing an emotional problem across 4 potential sources of support among Facebook users (n=162).

Figure 2.

Frequency of help-seeking intentions if experiencing suicidal thoughts across 4 potential sources of support among Facebook users (n=162).

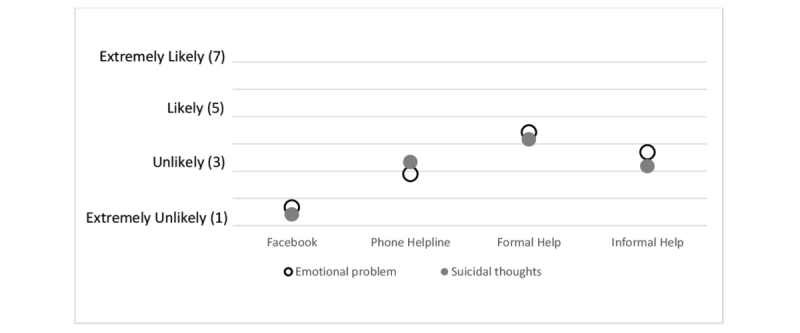

Comparisons of Help-Seeking Intentions by Source of Help

As shown in Figure 3, comparisons of help-seeking intentions through Facebook versus other potential means of help (formal, informal, or phone helpline) revealed highly significant differences, with veterans being less likely to seek help from Facebook than from any other source. This was true for help-seeking for both emotional problems and suicidal thoughts. For example, the mean level of help-seeking intentions via a phone helpline was significantly higher for both emotional problems (2.89; 95% CI 2.61 to 3.17, P<.001) and suicidal thoughts (3.33; 95% CI 3.00 to 3.66, P<.001) compared to Facebook. In addition, the mean level of help-seeking intentions was highest for formal sources for both emotional problems (4.42; 95% CI 4.20 to 4.65, P<.001) and suicidal thoughts (4.16; 95% CI 3.88 to 4.44, P<.001). Detailed data on comparisons of different help-seeking sources is contained in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Figure 3.

Help-seeking intentions for 4 potential sources of support among participants who use Facebook (n=162).

Help-Seeking Intentions Among Subgroups of Facebook Users

Results were mostly similar when we restricted analyses to participants who were frequent Facebook users (106/162) and active Facebook users (65/162) (see figures in Multimedia Appendix 1). Active Facebook users did show a small but significant 0.53-point increase (95% CI 0.12 to 0.94, P=.01) in intention to seek help from Facebook for emotional problems and a 0.33-point increase (95% CI 0.01 to 0.66, P=.047) in intention to seek help from Facebook for suicidal thoughts, compared to nonactive Facebook users. Among Facebook users who also used other forms of social media (42/162), help-seeking intentions via Facebook were not significantly different from those who exclusively used Facebook, either for emotional problems (1.90 vs 1.59; 95% CI –0.15 to 0.78, P=.18) or suicidal thoughts (1.58 vs 1.36; 95% CI –0.15 to 0.59, P=.25).

In examination of demographic groups of interest, results were again consistent with the overall sample. Among women (28/162), help-seeking intentions via Facebook were not significantly different from men for emotional problems. Finally, among participants younger than age 40 years (37/162), help-seeking intentions via Facebook were not significantly different from participants age 40 years and over, either for emotional problems or suicidal thoughts.

We identified a small subgroup (9/162) of participants who indicated intention to seek help for emotional problems or suicidal thoughts from Facebook (GHSQ score of 5 or more). These individuals had somewhat higher levels of help-seeking intentions more generally. Their mean help-seeking intentions using formal, informal, and phone sources for either emotional problems or suicidal thoughts was 4.83, which was 1.29 points (95% CI 0.45 to 2.13, P=.003) higher than other Facebook users.

Discussion

Principal Findings

The primary finding from this study is that social media appears to be a very undesirable venue for mental health help-seeking for VA patients with probable major depression. This finding remained true even among the most frequent users of Facebook and among individuals who used Facebook in an active way (which is more associated with positive mental health than passive use) [38]. Findings were also consistent whether the reason for help-seeking was a more mild emotional concern or something much more severe (suicidal thoughts).

The lack of interest in Facebook for help-seeking is all the more striking when compared to higher levels of interest in offline sources of help. The majority of our military veterans endorsed at least one venue they were likely to use for help-seeking. Mean help-seeking intentions for formal help and phone helplines in our sample were higher than in a prior study of Iraq/Afghanistan-era military veterans [39] and similar to prior studies involving Australian college students [40].

This study does not reveal why individuals do not intend to seek help from Facebook. However, we suspect several possible reasons for the large discrepancy in the likelihood of informal help-seeking via Facebook versus offline sources. First, many “Facebook friends” are not “real friends,” or at least not close ones. Prior empirical work has shown that only a small segment of Facebook friends are actually close, personal social connections [41]. It is this small group that is most likely to influence behavior in the real world [41]. Second, it may be stigmatizing to self-disclose mental health problems on Facebook. People have a strong tendency to present a positive self-image on Facebook [42], and stigma is a major barrier to help-seeking that occurs disproportionately among military veterans [43]. Third, interactions on Facebook are likely perceived as being more impersonal and lacking a human touch. So-called “broadcast communication,” which includes posts such as status updates that are sent out widely to Facebook friends [44], predominates on Facebook and perhaps contributes to such a perception. Fourth, participants may not have perceived Facebook as a trustworthy platform in which to openly discuss mental health matters. Concerns about privacy might stifle mental health help-seeking, and some research has suggested trust in social media is low in the United States and acts as a predictor of whether one engages in self-disclosure of health issues online [45]. There are areas within Facebook that are less susceptible to concerns related to impersonal communication and anonymity. For example, closed support groups, including ones tailored to veterans, would likely be more socially acceptable forums within Facebook for help-seeking or exchange of social support [46]. Last, because many of the most common reasons for using Facebook are unrelated to health concerns, it may be that, for military veterans, Facebook simply does not come to mind as a help-seeking tool.

In addition, help-seeking intentions via Facebook may be more favorable in individuals younger than our sample population, such as millennials who have grown up with Web 2.0 and social media [47]. Prior research has even shown that adolescents may disclose more personal information on social media than in person [48]. It is also encouraging that when individuals do self-disclose negative emotions on Facebook, they often receive objective social support, even more so if the person is depressed [49]. Researchers are also developing tools to help detect risk for suicide based on content of social media posts, which could in theory lead to ways to reach out to individuals online even if they do not actively seek out help themselves [50].

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the lack of measurement of actual help-seeking or treatment utilization, given that research has found stated intentions of help-seeking may not translate into actual help-seeking behaviors [51]. Likewise, we were unable to capture whether veterans ever posted on Facebook in the act of help-seeking. Although emotional problems and even suicidality were relatively common in our sample, results must be interpreted cautiously as our survey queried intentions to seek help in a hypothetical scenario. Additionally, survey order effects could have influenced results such that individuals underreported Facebook help-seeking intentions. Because the item on Facebook help-seeking intentions was placed after items on other sources of help such as friends and family, respondents may have perceived Facebook as being mutually exclusive from these options. Finally, results are not likely generalizable to other populations not well represented in our sample of military veterans, including veterans who lack any social supports, women, or youth.

Conclusions

Our results should not be interpreted as negating the relevance of tools, such as one recently rolled out by Facebook [28], to assist individuals actively experiencing suicidal ideation. Rather, we believe our results frame the utility of such tools as being best suited to the select few who both experience suicidality and are comfortable using Facebook in a crisis. Overall, this study suggests Facebook in its current form is by no means perceived as a go-to source for mental health help-seeking among veterans with depression. Instead, more traditional sources of support appear to be the most viable venues for help-seeking in this population.

Acknowledgments

This paper was funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D), and the HSR&D Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care. ART’s work was supported in part by a Career Development Award from the Veterans Health Administration HSR&D (CDA 14-428). The US Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Abbreviations

- GHSQ

General Help-Seeking Questionnaire

- PHQ-8

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PTSD

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- VA

US Department of Veterans Affairs

Sociodemographic and clinical variables examined.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Statista: Facebook users worldwide 2017. [2017-09-19]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

- 2.Social Media Fact Sheet. Washington: Pew Research Center; [2017-09-19]. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facebook has 50 minutes of your time each day: it wants more. New York: New York Times; 2016. May 06, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/06/business/facebook-bends-the-rules-of-audience-engagement-to-its-advantage.html . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabi RL, Prestin A, So J. Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013 Oct;16(10):721–727. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron B. Facebook newsroom: veterans on Facebook. 2014. Nov 11, [2018-01-24]. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2014/11/veterans-on-facebook/

- 6.Bush NE, Wheeler WM. Personal technology use by U.S. military service members and veterans: an update. Telemed J E Health. 2015 Apr;21(4):245–258. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith A. Fact Tank: 6 new facts about Facebook. Washington: Pew Research Center; 2014. Feb 03, [2017-10-25]. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/02/03/6-new-facts-about-facebook/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houston TK, Volkman JE, Feng H, Nazi KM, Shimada SL, Fox S. Veteran internet use and engagement with health information online. Mil Med. 2013 Apr;178(4):394–400. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCully SN, Don BP, Updegraff JA. Using the Internet to help with diet, weight, and physical activity: results from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2612. http://www.jmir.org/2013/8/e148/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen ER, Helmuth ED, Marshall GN, Schell TL, PunKay M, Kurz J. Using Facebook to recruit young adult veterans: online mental health research. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(2):e63. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3996. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2015/2/e63/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno MA, Christakis DA, Egan KG, Jelenchick LA, Cox E, Young H, Villiard H, Becker T. A pilot evaluation of associations between displayed depression references on Facebook and self-reported depression using a clinical scale. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012 Jul;39(3):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9258-7. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21863354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno MA, Jelenchick LA, Egan KG, Cox E, Young H, Gannon KE, Becker T. Feeling bad on Facebook: depression disclosures by college students on a social networking site. Depress Anxiety. 2011 Jun;28(6):447–455. doi: 10.1002/da.20805. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21400639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen JE, Bantum EO, Gorlick A, Stanton AL. Engagement with a social networking intervention for cancer-related distress. Ann Behav Med. 2015 Apr;49(2):154–164. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9643-6. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25209353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rait MA, Prochaska JJ, Rubinstein ML. Recruitment of adolescents for a smoking study: use of traditional strategies and social media. Transl Behav Med. 2015 Sep;5(3):254–259. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0312-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26327930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen ER, Helmuth ED, Marshall GN, Schell TL, PunKay M, Kurz J. Using Facebook to recruit young adult veterans: online mental health research. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(2):e63. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3996. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2015/2/e63/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gowen K, Deschaine M, Gruttadara D, Markey D. Young adults with mental health conditions and social networking websites: seeking tools to build community. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2012;35(3):245–250. doi: 10.2975/35.3.2012.245.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Settanni M, Marengo D. Sharing feelings online: studying emotional well-being via automated text analysis of Facebook posts. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1045. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01045. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCloskey W, Iwanicki S, Lauterbach D, Giammittorio DM, Maxwell K. Are Facebook friends helpful? Development of a Facebook-based measure of social support and examination of relationships among depression, quality of life, and social support. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015 Sep;18(9):499–505. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellison N, Gray R, Vitak J, Lampe C, Fiore A. Calling All Facebook Friends: Exploring Requests for Help on Facebook. [2018-01-24]. https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM13/paper/download/6130/6354 .

- 20.Akkin GH, Demir T, Gokalp OB, Kadak M, Poyraz B. Use of social network sites among depressed adolescents. Behav Inf Technol. 2017;36:517–523. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds M. Facebook is testing AI tools to help prevent suicide. 2017. Mar 01, [2017-09-19]. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2123225-facebook-is-testing-ai-tools-to-help-prevent-suicide/

- 22.International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):413–426. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/10885160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Hwang I, Chiu W, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Alonso J, Borges G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Hu C, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Kostyuchenko S, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Levinson D, Matschinger H, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Scott KM, Stein DJ, Tomov T, Viana MC, Nock MK. Treatment of suicidal people around the world. Br J Psychiatry. 2011 Jul;199(1):64–70. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084129. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21263012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanielian T, Jaycox L. RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research. [2018-01-24]. Invisible wounds of war: psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2008/RAND_MG720.pdf .

- 25.McFall M, Malte C, Fontana A, Rosenheck RA. Effects of an outreach intervention on use of mental health services by veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2000 Mar;51(3):369–374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stecker T, Fortney JC, Sherbourne CD. An intervention to increase mental health treatment engagement among OIF Veterans: a pilot trial. Mil Med. 2011 Jun;176(6):613–619. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Feb;3(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS data brief, no 241. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kauer SD, Mangan C, Sanci L. Do online mental health services improve help-seeking for young people? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e66. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3103. http://www.jmir.org/2014/3/e66/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Dea B, Campbell A. Healthy connections: online social networks and their potential for peer support. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;168:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012 Feb 21;184(3):E191–E196. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=22184363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson C, Deane F, Ciarrochi J. Measuring help seeking intentions: properties of the General Help Seeking Questionnaire. Can J Couns Psychot. 2005;39(1):15–28. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2580&context=hbspapers. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deane FP, Wilson CJ. Considerations for specifying problem-types, help-sources and scoring the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) 2007. [2017-09-19]. http://www.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@health/@iimh/documents/doc/uow039041.pdf .

- 35.Greenwood S, Perrin A, Duggan M. Social media update 2016. Washington: Pew Internet and American Life Project; [2018-01-24]. http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2016/11/10132827/PI_2016.11.11_Social-Media-Update_FINAL.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Survey Research. Washington: Pew Research Center; [2017-09-19]. http://www.pewresearch.org/methodology/u-s-survey-research/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verduyn P, Lee DS, Park J, Shablack H, Orvell A, Bayer J, Ybarra O, Jonides J, Kross E. Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: experimental and longitudinal evidence. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2015 Apr;144(2):480–488. doi: 10.1037/xge0000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verduyn P, Ybarra O, Résibois M, Jonides J, Kross E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2017;11:274–302. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blais RK, Renshaw KD. Stigma and demographic correlates of help-seeking intentions in returning service members. J Trauma Stress. 2013 Feb;26(1):77–85. doi: 10.1002/jts.21772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson CJ, Deane FP. Help-negation and suicidal ideation: the role of depression, anxiety and hopelessness. J Youth Adolesc. 2010 Mar;39(3):291–305. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bond RM, Fariss CJ, Jones JJ, Kramer ADI, Marlow C, Settle JE, Fowler JH. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature. 2012 Sep 13;489(7415):295–298. doi: 10.1038/nature11421. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22972300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, Shablack H, Jonides J, Ybarra O. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e69841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069841. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JSL, Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015 Jan;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke M, Kraut R. The relationship between Facebook use and well-being depends on communication type and tie strength. J Comput-Mediat Commun. 2016;21:265–281. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin WY, Zhang X, Song H, Omori K. Health information seeking in the Web 2.0 age: trust in social media, uncertainty reduction, and self-disclosure. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;56:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whealin JM, Jenchura EC, Wong AC, Zulman DM. How veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid health conditions utilize eHealth to manage their health care needs: a mixed-methods analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Oct 26;18(10):e280. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5594. http://www.jmir.org/2016/10/e280/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costin DL, Mackinnon AJ, Griffiths KM, Batterham PJ, Bennett AJ, Bennett K, Christensen H. Health e-cards as a means of encouraging help seeking for depression among young adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(4):e42. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1294. http://www.jmir.org/2009/4/e42/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christofides E, Muise A, Desmarais S. Information disclosure and control on Facebook: are they two sides of the same coin or two different processes? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009 Jun;12(3):341–345. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park J, Lee DS, Shablack H, Verduyn P, Deldin P, Ybarra O, Jonides J, Kross E. When perceptions defy reality: the relationships between depression and actual and perceived Facebook social support. J Affect Disord. 2016 Aug;200:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryan CJ, Butner JE, Sinclair S, Bryan ABO, Hesse CM, Rose AE. Predictors of emerging suicide death among military personnel on social media Networks. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2017 Jul 28;:1. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Younes N, Chollet A, Menard E, Melchior M. E-mental health care among young adults and help-seeking behaviors: a transversal study in a community sample. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e123. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4254. http://www.jmir.org/2015/5/e123/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sociodemographic and clinical variables examined.