Abstract

Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) is commonly used for unresectable intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). TACE is usually well-tolerated. We report a case of a patient who presented with a gastrointestinal bleed from TACE. A 64-year-old man presented with chronic hepatitis C cirrhosis and multifocal bilobar HCC. He had previously undergone multiple TACE sessions, radiofrequency ablation and stereotactic body radiation therapy. In the evening of his TACE procedure, he developed abdominal pain and haematemesis. An oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) showed non-bleeding oesophageal varices and ulcerations in the stomach and duodenum, with pathology demonstrating mucosal necrosis. The patient recovered and was discharged on omeprazole. While TACE is considered safe with most patients only experiencing postembolisation syndrome, vascular complications have been reported. In our patient, OGD revealed ulcerations, with biopsies confirming ischaemic ulceration. The likely aetiology was seepage of the embolic particles into neighbouring arteries. Patients should be carefully selected for TACE and monitored post procedure.

Keywords: Gi bleeding, ulcer, hepatitis C, hepatic cancer, interventional radiology

Background

Hepatic transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) is commonly used for unresectable intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Child-Pugh classes A–B, performance status 0). Current consensus from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the American Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association is that conventional TACE is preferred compared with bland embolisation given modest survival benefit.1 2 TACE is very well-tolerated, with complications ranging from vascular, non-vascular and procedural site complications.3 Non-vascular complications range from milder postembolisation syndrome, which is usually a self-limiting illness of fatigue, fever and abdominal pain, to more morbid acute liver failure, liver abscess and also a biloma formation. Vascular complications are rarer but can include ischaemia to the gall bladder, pancreas, duodenum, stomach, spinal cord or liver. The foregut derivatives have a dual blood supply and therefore are relatively less prone to ischaemia, but these complications have been reported in the past.4 5 We report a case of a patient presented with significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding from TACE.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old man with history of chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection with underlying cirrhosis (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium [MELD-Na] score of 8, Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A) was noted to have multifocal bilobar HCC, with the largest lesion measuring 4.6 cm in diameter in segment 7 of the liver. An arteriogram prior to his initial TACE showed conventional anatomy, and he was not noted to have any contraindication to the procedure. He received four TACE sessions to his right lobe tumour and radiofrequency ablation for smaller left lobe lesions. Given incomplete response he subsequently received three cycles of stereotactic body radiation therapy for the caudate lobe lesions.

Most recently the patient received his fifth TACE procedure for a lesion measuring 1.8 cm in the left lobe of the liver. He developed right upper quadrant pain and nausea on the same day of the procedure and then had dark bloody emesis. His vital signs were notable for hypertension and physical examination demonstrated right upper quadrant tenderness.

Investigations

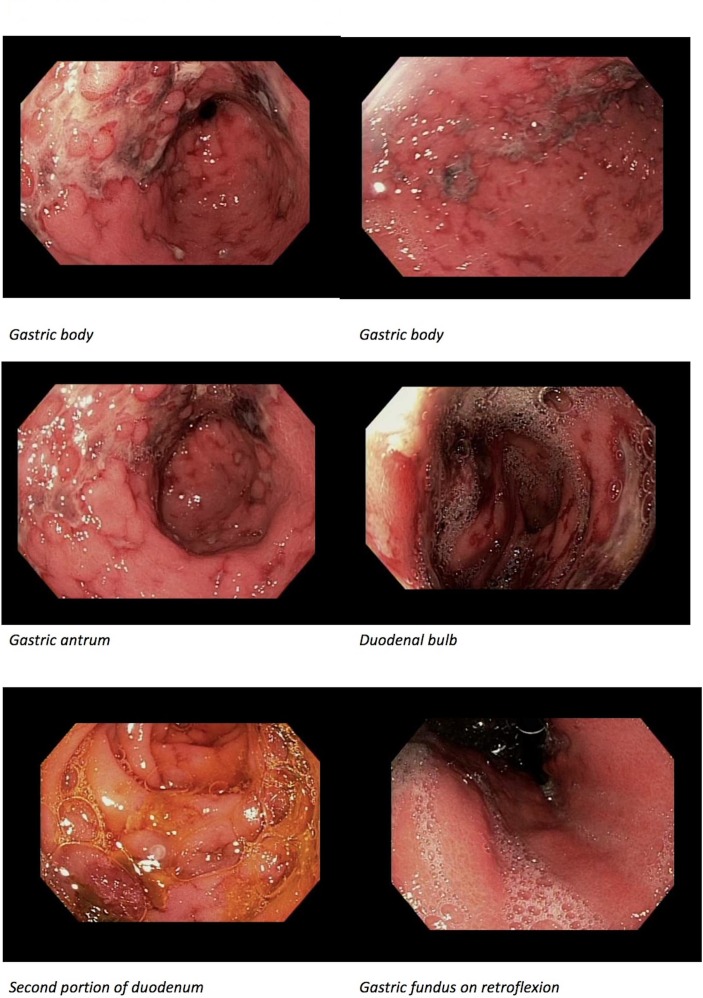

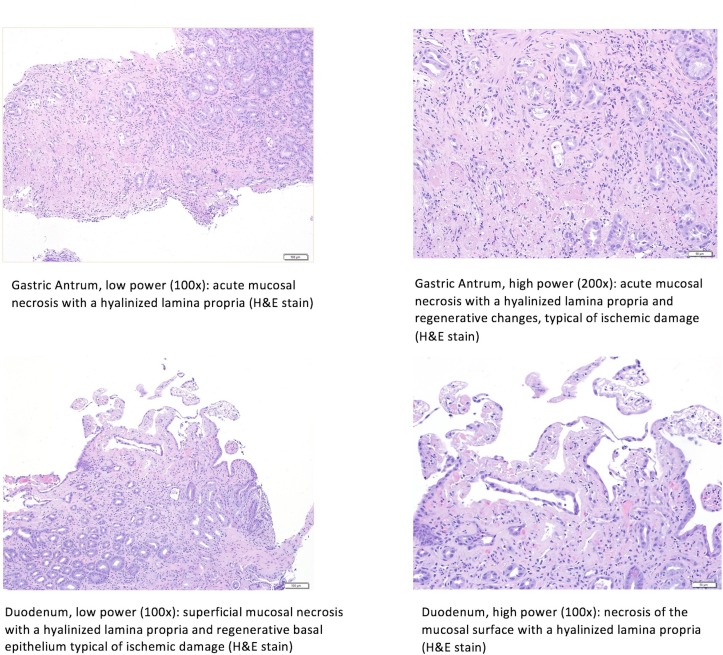

Initial haemoglobin, liver function tests and basic metabolic panel were within normal limits, although on repeat check his haemoglobin was 11.1 g/dL (down from 14.6 g/dL), with mild aminotransferase elevations (Alanine transaminase [ALT] 113 IU/L (normal range <35 IU/L) and Aspartate transaminase [AST] 143 IU/L (normal range 8–30 IU/L)). The patient was initiated on intravenous infusion of octreotide and pantoprazole, and was given intravenous antibiotics. He underwent an oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD), which showed non-bleeding grade I–II oesophageal varices, and several small-sized to large-sized superficial and cratered ulcerations in the mid-lower body, antrum and prepyloric region thought to be ischaemic in aetiology (figure 1). Several similar ulcerations were also seen in the duodenum. These lesions were biopsied, with pathology demonstrating acute mucosal necrosis (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy findings of multiple, large, cratered ulcers in gastric body, gastric antrum, duodenal bulb and second portion of the duodenum.

Figure 2.

Histological findings of both the stomach and duodenum. Both low-power (100×) and high-power (200×) magnification of the stomach show acute mucosal necrosis with hyalinised propria with regenerative changes consistent with acute ischaemic injury. Both low-power (100×) and high-power (200×) magnification of the duodenum show superficial mucosal necrosis with hyalinised propria and regenerative basal epithelium typical of ischaemic damage.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient recovered over the next 2 days, with resolution of the abdominal pain and nausea, without any further episodes of haematemesis, with the haemoglobin stable at 12.1 g/dL and a steady decline in transaminases. He was eventually discharged with omeprazole orally twice daily and was advised to avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Discussion

While TACE is considered generally safe with most patients only experiencing postembolisation syndrome, vascular complications have been reported.3 5 In a patient with cirrhosis presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding after a procedure such as TACE, careful consideration must be made to rule out alternative causes of bleeding, such as bleeding oesophageal varices. In our patient, OGD revealed non-bleeding oesophageal varices, and biopsy of the gastric and duodenal lesions showed pathology that was consistent with ischaemic ulceration. It has been suggested that vascular ischaemic events may be due to seepage of the embolic particles into the neighbouring arteries, from occlusion of arteries from repeated TACE procedures, from non-target embolisation due to anatomical variants of the hepatic and gastric/small intestinal vasculature, or from human error.5 A study published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology noted mucosal lesions in 13 out of 29 patients (45%) who underwent TACE, and listed the possible aetiologies to be ischaemia, or toxic effects of antineoplastic drugs, or from stress.6 However, to date there is no published report of gastric ulcerations post-TACE that has endoscopic and pathological evidence of ischaemic aetiology. Ischaemia of other organs leading to acute pancreatitis (1.7%–40%), acute cholecystitis (0.3%–5.5%), splenic infarction (0.08%–1.4%) and spinal cord injury (0.3%–1.2%) has also been reported.7–9

In our patient, a common origin of coeliac artery and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), an anatomical variation, was noted during the initial arteriogram, but the blood supply of the liver was found to be normal. There was no hepatic blood supply from the SMA. The left hepatic artery supplying the left lobe was selected and catheterised, making non-target embolisation unlikely. Likely aetiologies for the complication resulting in gastric and duodenal ulceration with bleeding in our patient include seepage of embolic particles from the target artery and/or vascular compromise from arterial occlusion from repeated TACE procedures.

TACE has been shown to have mortality benefit compared with bland embolisation alone. Significant complications have been reported in a small minority of patients. Careful consideration should be made in selecting patients appropriate for TACE, with appropriate monitoring of complications post procedure.

Learning points.

While the use of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) for hepatocellular carcinoma is generally considered safe, there are reports of vascular complications post procedure that may need to be investigated.

TACE can cause arterial occlusion that may result in ulcer formation in the upper gastrointestinal tract causing gastrointestinal bleeding.

Careful patient selection is key to prevent complications related to the TACE procedure.

Endoscopic evaluation is warranted in patients who present with gastrointestinal bleeding after a TACE procedure to better determine the aetiology of blood loss.

Footnotes

Contributors: SPC performed key background research, data collection and preliminary manuscript creation. AP helped procure endoscopic images, along with final edits to the manuscript. HC helped perform final edits to the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005;42:1208–36. 10.1002/hep.20933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz RE, Abou-Alfa GK, Geschwind JF, et al. . Nonoperative therapies for combined modality treatment of hepatocellular cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB 2010;12:313–20. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00183.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneeweiß S, Horger M, Ketelsen D, et al. . [Complications after TACE in HCC]. Rofo 2015;36:79–82. 10.1055/s-0034-1369532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. . Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007;30:6–25. 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung TK, Lee CM, Chen HC. Anatomic and technical skill factor of gastroduodenal complication in post-transarterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 280 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:1554 10.3748/wjg.v11.i10.1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirakawa M, Iida M, Aoyagi K, et al. . Gastroduodenal lesions after transcatheter arterial chemo-embolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:837–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazine A, Fetohi M, Berri MA, et al. . Spinal cord ischemia secondary to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2014;8:264–9. 10.1159/000368075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae SI, Yeon JE, Lee JM, et al. . A case of necrotizing pancreatitis subsequent to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 2012;18:321–5. 10.3350/cmh.2012.18.3.321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah RP, Brown KT. Hepatic arterial embolization complicated by acute cholecystitis. Semin Intervent Radiol 2011;28:252–7. 10.1055/s-0031-1280675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]