Abstract

OBJECTIVE

In October 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) for the routine immunization schedule for 11- to 12-year-old boys. Before October 2011, HPV4 was permissively recommended for boys. We conducted a study in 2010 to provide data that could guide efforts to implement routine HPV4 immunization in boys. Our objectives were to describe primary care physicians’: 1) knowledge and attitudes about human papillomavirus (HPV)-related disease and HPV4, 2) recommendation and administration practices regarding HPV vaccine in boys compared to girls, 3) perceived barriers to HPV4 administration in boys, and 4) personal and practice characteristics associated with recommending HPV4 to boys.

METHODS

We conducted a mail and Internet survey in a nationally representative sample of pediatricians and family medicine physicians from July 2010 to September 2010.

RESULTS

The response rate was 72% (609 of 842). Most physicians thought that the routine use of HPV4 in boys was justified. Although it was permissively recommended, 33% recommended HPV4 to 11- to 12-year-old boys and recommended it more strongly to older male adolescents. The most common barriers to HPV4 administration were related to vaccine financing. Physicians who reported recommending HPV4 for 11- to 12-year-old boys were more likely to be from urban locations, perceive that HPV4 is efficacious, perceive that HPV-related disease is severe, and routinely discuss sexual health with 11- to 12-year-olds.

CONCLUSIONS

Although most physicians support HPV4 for boys, physician education and evidence-based tools are needed to improve implementation of a vaccination program for males in primary care settings.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, immunization, physician attitudes

The quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) protects vaccinated individuals from the cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV) strains, 16 and 18, and the wart-causing strains, 6 and 11. Until October 2011, HPV4 was recommended only for females; however, approximately 7000 HPV-associated cancers and 250,000 cases of genital warts occur in males in the United States annually, with the highest risk for immuno-compromised men, and men who have sex with men.1–8 Vaccination of men reduces disease caused by these HPV types in men and also reduces transmission of HPV to females.3 In 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration licensed HPV4 for use in males aged 9 through 26 years for prevention of genital warts.9 Soon after licensure, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) provided guidance that HPV4 may be used in males aged 9 to 26 years but did not recommend HPV4 for routine use.10 The vaccine was included in the Vaccines for Children program to enable providers to immunize eligible boys aged 9 through 19. In October 2011, the ACIP modified its guidance and recommended HPV4 for routine use in boys.

Before our study, conducted in 2010 when HPV4 was permissively recommended for boys, limited data were available regarding primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to HPV4 for males. These data were needed to aid the ACIP in its consideration of the acceptability of an HPV vaccination program for males among primary care providers and to guide implementation efforts if a recommendation for routine use were made.11–15 Because HPV vaccine coverage among girls remained below 50% three years after it was recommended and coverage improved less than for other adolescent vaccines,16 challenges to implementation were expected for boys. Information about the characteristics of physicians who were recommending HPV4 for boys and the circumstances under which they recommended it when it was permissively recommended by the ACIP could identify interventions to increase physicians’ use of HPV4. Therefore, we conducted a survey among a nationally representative sample of pediatricians and family medicine (FM) physicians to: 1) describe their knowledge and attitudes about HPV-related disease and HPV4 for males, 2) describe their recommendation and administration practices regarding HPV vaccine in boys compared to girls, 3) describe perceived barriers to HPV4 administration in boys, and 4) identify physician and practice characteristics associated with recommending HPV4 to boys.

Methods

Study Setting

The Vaccine Policy Collaborative Initiative, a program designed collaboratively with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to assess primary care physicians’ attitudes about vaccine-related issues, administered a survey to a national network of pediatricians and FM physicians. The human subjects review board at the University of Colorado approved this study as exempt research.

Population

We conducted the survey among networks of physicians who were previously recruited from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and who agreed to respond to several surveys annually.17 After obtaining twice the number of recruits needed for each network, a quota strategy was applied to assure the representativeness of the samples.17,18 In a previous evaluation, demographic characteristics, practice attributes, and reported attitudes about a range of vaccination issues were generally similar when network physicians were compared with physicians of the same specialty randomly sampled from the American Medical Association master physician listing.17

Survey Design

We developed the survey instrument in collaboration with the CDC. On the basis of the Health Belief Model, we predicted that physicians’ recommendation for HPV4 in boys is affected by their perceptions about barriers to HPV4 administration, males’ susceptibility to HPV infection and HPV-related diseases, severity of HPV-related diseases, and the benefit of HPV4.19 Because previous studies of the HPV vaccine have indicated that some physicians link counseling about the vaccine to counseling about sexual health,14,20,21 we also asked about physicians’ practices related to discussing sexual health with boys and girls at different ages. We predicted that discussing sexual health issues would be a cue to action for recommending HPV4.

The survey also included questions about physicians’ and practices’ characteristics, physicians’ current practices related to recommendation for and administration of the HPV vaccine, physicians’ knowledge about HPV infection and HPV4 among males, the topics physicians would emphasize when discussing HPV4 with male patients, and physicians’ intention to recommend HPV4 for boys if recommended for routine use by the ACIP. The survey was pretested in a community advisory panel consisting of 3 pediatricians and 3 FM physicians from across the country and was pilot tested among 41 pediatricians and FM physicians.

We measured physicians’ perceived barriers to HPV4 administration to boys, perceptions of HPV4 and HPV-related diseases, current practices regarding recommendation of the HPV vaccine, topics of emphasis when discussing HPV4 with boys, and intention to recommend HPV4 for boys if recommended for routine use by the ACIP using 4-point Likert scales. We measured physicians’ current administration practices using 5 choices ranging from “never/almost never” to “always/almost always.” We measured physicians’ knowledge about the HPV vaccine and HPV-related diseases and perception of HPV4 efficacy in males using statements to which respondents answered “agree,” “disagree,” or “don’t know/not sure.” Finally, we measured physicians’ discussion of sexual health at different ages using “yes” or “no” choices.

Survey Administration

The survey was administered between July 2010 and September 2010 by Internet or regular mail based on physicians’ preferences. The Internet survey was administered using a Web-based program (Vovici Corp, Dulles, Va). The Internet group received an initial e-mail with a link to the survey and up to 8 e-mail reminders to complete the survey, while the mail group received an initial mailing and up to 2 additional mailed surveys at 2-week intervals. The Internet nonresponders also received up to 2 paper surveys by mail.

Analytic Methods

Internet and mail surveys were pooled for all analyses, as provider attitudes have been found to be comparable when obtained by either method.22 We compared pediatricians and FM physicians by chi-square tests for questions with dichotomous responses and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for questions with Likert scale responses. Because pediatricians’ and FM physicians’ responses were similar, they were combined for most subsequent analyses. The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to compare the strength of recommendation for HPV across different age groups and the frequency of discussing sexual health issues across different age groups.

Perceived barriers to HPV4 administration in boys were grouped into 4 categories: vaccine financing issues (4 questions), parental attitudes about HPV4 for boys (5 questions), logistic barriers to HPV administration (4 questions), and physicians’ attitudes about the safety of HPV4 and its effect on boys’ behavior (4 questions). Susceptibility was measured with 3 questions, and severity was measured with 3 questions. A Cronbach alpha value was calculated for each set of questions measuring a specific concept (barriers, susceptibility, and severity) to determine whether physicians responded in a consistent manner. Because the Cronbach alpha value was greater than 0.70 for each concept, we created scales for the 4 barrier concepts, susceptibility, and severity by assigning a number value from 0 to 4 for each response, adding the numbers, and dividing by the number of questions in the set.

We compared physicians who reported recommending HPV4 to their 11- to 12-year-old male patients (recommend strongly or recommend, but not strongly) to physicians who reported making no recommendation or recommending against HPV4 in terms of physician characteristics (age, gender, and specialty), practice characteristics (region of country, urban vs rural, proportion of patients 11 to 18 years old, and proportion of patients with private insurance), perceived barriers, susceptibility, severity, benefit, and cue to action by using t tests, Wilcoxon tests, and chi-square tests, as appropriate. Predictor variables with a P value of .25 or less were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Variables were retained in the final model if their P values were <.05.

Results

Response Rates and Sample Characteristics

Our response rate was 72% overall, with 82% of pediatricians (343 of 419) and 63% of FM physicians (266 of 423) responding. The response rate was 76% for the Internet survey group (404 of 533) and 66% for the mailed survey group (205 of 309). Respondents were similar to nonrespondents (Table 1). However, respondents were more likely to be women, more recent medical school graduates, and more likely to practice in an academic, community health center, or public health setting compared to nonrespondents.

Table 1.

Comparison of Respondents and Nonrespondents and Additional Characteristics of Respondents’ Practices

| Family Medicine

|

Pediatricians

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Nonrespondents (n = 157, 37%) | Respondents (n = 266, 63%) | Nonrespondents (n = 76, 18%) | Respondents (n = 343, 82%) |

| Year of MD/DO school graduation, median | 1987 | 1986 | 1983.5 | 1988* |

| Female, % | 25 | 46* | 49 | 63* |

| Region of country, % | ||||

| Midwest | 32 | 28 | 22 | 20 |

| Northeast | 15 | 16 | 21 | 23 |

| South | 31 | 34 | 38 | 35 |

| West | 22 | 22 | 18 | 23 |

| Practice location, % | ||||

| Rural | 23 | 27 | 15 | 12 |

| Urban, inner city | 29 | 28 | 35 | 45 |

| Urban, non–inner city/suburban | 48 | 45 | 51 | 43 |

| Type of practice, % | ||||

| Health maintenance organization | 6 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Private practice | 77 | 75 | 82 | 78 |

| Community or hospital based | 17 | 23* | 18 | 17 |

| Proportion of 11- to 18-year-old patients | ||||

| <10% | 51 | 3 | ||

| 10–29% | 41 | 28 | ||

| 30–39% | 4 | 33 | ||

| ≥40% | 4 | 35 | ||

| Proportion of uninsured patients | ||||

| <10% | 71 | 85 | ||

| 10–24% | 20 | 13 | ||

| ≥25% | 9 | 3 | ||

| Proportion of patients with Medicaid or SCHIP, % | ||||

| <10% | 44 | 28 | ||

| 10–24% | 23 | 25 | ||

| 25–49% | 19 | 23 | ||

| ≥50% | 14 | 24 | ||

| Proportion of patients with private insurance, % | ||||

| <25% | 22 | 18 | ||

| 25–49% | 22 | 18 | ||

| 50–74% | 29 | 29 | ||

| ≥75% | 27 | 35 | ||

| Proportion of Latino patients, % | ||||

| <10% | 70 | 53 | ||

| 10–24% | 15 | 28 | ||

| ≥25% | 15 | 19 | ||

| Proportion of black/African American patients, % | ||||

| <10% | 67 | 49 | ||

| 10–24% | 22 | 30 | ||

| >25% | 11 | 20 | ||

SCHIP = State Children’s Health Insurance Program.

P < .05 for comparison between respondents and nonrespondents within specialty.

Knowledge and Attitudes About HPV-related Disease and HPV4 for Males

Although most physicians agreed that most male subjects with HPV infection are asymptomatic, 25% disagreed or were unsure. Although the majority agreed that genital warts and cervical cancers are caused by different HPV types, 48% disagreed or were unsure. Most physicians (85%) agreed that HPV infection causes some penile, anal, and oral cancers in male subjects, and 64% agreed that the incidence of HPV-associated anal cancer is higher among men who have sex with men. Seventy-four percent agreed that HPV4 is efficacious for preventing genital warts in male subjects.

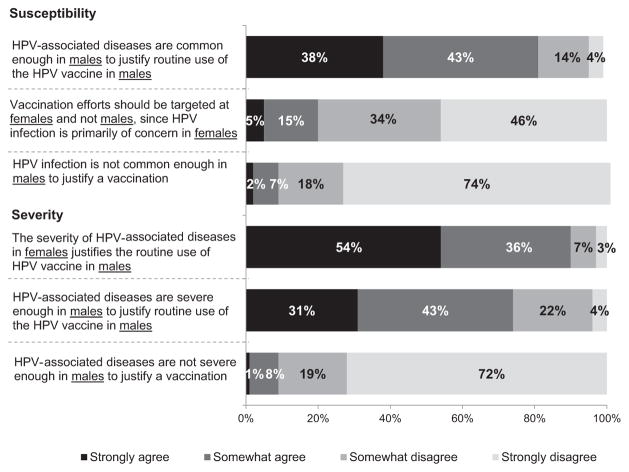

More physicians strongly agreed that “since HPV is transmitted from males to females, HPV-related disease is severe enough in females to justify routine use of HPV4 in males” than strongly agreed that “HPV-related disease is severe enough in males to justify the routine use of HPV4 in males” (Fig. 1). Fifty-four percent of physicians strongly or somewhat agreed that it is necessary to discuss issues of sexuality before recommending HPV4 to their male patients. When discussing HPV4, 65% would strongly emphasize prevention of genital warts in the patient himself, 64% would strongly emphasize prevention of cervical cancer in the patient’s female partners, and 60% and 56% would strongly emphasize vaccine safety and efficacy, respectively.

Figure 1.

Physicians’ attitudes about HPV4 for boys for pediatricians and family physicians combined (n =602). Excluded are physicians who responded, “I do not see patients in this group” (total excluded <2%). Some percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding.

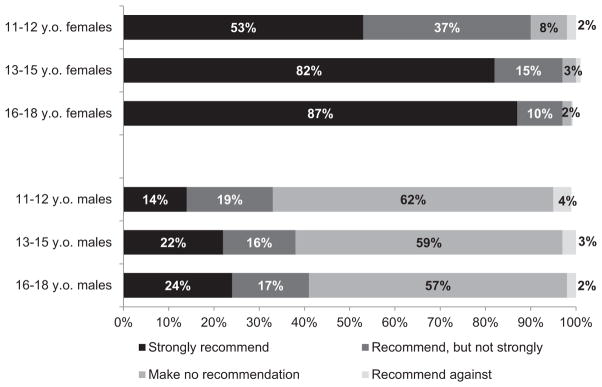

Practices Related to HPV4 in Girls and Boys

The majority of physicians reported that they routinely recommend the HPV vaccine for girls, while a minority reported that they routinely recommend HPV4 for boys (Fig. 2). For both genders and subspecialties, physicians were more likely to strongly recommend the vaccine for adolescents aged 13 to 15 and 16 to 18 compared to 11-to 12-year-olds (P < .0001 for girls, P = .01 for boys). Ninety-two percent of physicians reported that they administer the HPV vaccine to girls in their practices, and 31% reported that they administer the vaccine to boys.

Figure 2.

Physicians’ strength of recommendation for HPV vaccine in girls and boys in different age groups (n = 609). The survey was conducted between July 2010 and September 2010 before the recommendation for routine vaccination of boys with HPV4. Excluded physicians who responded, “I do not see patients in this age group” (total excluded <2%). Some percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding. P < .05 for Cochran-Armitage test for trend for percent who “strongly recommend” and “recommend, but not strongly” across the 3 age groups for both genders.

When asked about the strength of their recommendation if the ACIP were to recommend HPV4 for routine use among boys, only 37% of physicians reported that they intended to strongly recommend HPV4 for 11- to 12-year-old boys, 42% intended to recommend but not strongly, 17% intended to make no recommendation, and 3% intended to recommend against. Eighty-four percent of physicians reported they would strongly recommend HPV4 for boys who have disclosed that they are homosexual or bisexual.

When physicians were asked whether they routinely discuss sexual activity at health maintenance visits for each gender by age group, 31% reported that they discuss this topic with 11- and 12-year-old girls and 27% discuss with 11- and 12-year-old boys. More than 80% reported discussing sexual activity with 13- to 15-year-olds and 16- to 18-year-olds. For a similar question about discussion of sexual orientation, 11% of physicians routinely discuss this topic with both 11- to 12-year-old boys and girls, 37% discuss with both 13- to 15-year-old boys and girls, and 52% discuss with both 16- to 18-year-old boys and girls. Pediatricians’ and FM physicians’ practices regarding discussion of sexual health were not statistically different.

Barriers to HPV4 Administration in Boys

The most commonly reported barriers to HPV4 administration if recommended for routine use in boys were related to vaccine financing, with 89% of physicians reporting at least one barrier in this category (Table 2). Barriers related to physicians’ perceptions of parental attitudes about HPV4 for boys and the logistics of HPV4 administration were also commonly reported. The most common parental attitude barrier was “parents not thinking that HPV4 is necessary for their sons” and the most common logistic barrier was “infrequent office visits made by male adolescent patients.” Barriers related to physicians’ attitudes about the safety of HPV4 and the effect of HPV4 vaccination on boys’ behavior were uncommon.

Table 2.

Perceived Barriers to HPV4 Administration if Recommended for Routine Use in Boys, Pediatricians and Family Medicine Physicians Combined (N = 593)*

| Barrier | Major Barrier, % | Somewhat a Barrier, % | Minor Barrier, % | Not a Barrier, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine financing issues | ||||

| Failure of some insurance companies to cover HPV4 for boys | 56 | 27 | 8 | 8 |

| Lack of adequate reimbursement for vaccination | 49 | 27 | 12 | 11 |

| Parents unable to pay the out-of-pocket cost for vaccine | 48 | 28 | 13 | 11 |

| The up-front costs for my practice to purchase the vaccine | 24 | 27 | 23 | 26 |

| Parental attitudes about HPV4 for boys | ||||

| Parents not thinking that HPV4 is necessary for their sons | 19 | 45 | 29 | 7 |

| Parents’ opposition to HPV4 vaccination for moral or religious reasons | 13 | 26 | 46 | 15 |

| Parents’ concern about the safety of HPV4 for their sons | 11 | 33 | 43 | 13 |

| Parents’ concern that vaccination may encourage earlier sexual behavior | 6 | 25 | 41 | 28 |

| Parents’ concern that vaccination may encourage riskier sexual behavior | 5 | 25 | 42 | 28 |

| Logistic barriers to HPV4 administration | ||||

| Infrequent office visits made by male adolescent patients | 12 | 38 | 34 | 17 |

| Difficulty ensuring completion of 3-dose vaccine series | 11 | 35 | 41 | 13 |

| The time it will take me to discuss HPV4 | 7 | 19 | 41 | 34 |

| General administrative a burden to my practice | 7 | 18 | 32 | 43 |

| Providers’ attitudes about the safety of HPV4 and effect of HPV4 vaccination on boys’ behavior | ||||

| My concern about the safety of HPV4 for boys | 4 | 7 | 21 | 69 |

| My concern that vaccination may encourage riskier sexual behavior | 1 | 5 | 13 | 82 |

| My concern that vaccination may encourage earlier sexual behavior | 1 | 4 | 11 | 85 |

| My opposition to HPV4 vaccination for moral or religious reasons | 1 | 1 | 3 | 95 |

HPV = human papillomavirus; HPV4 = quadrivalent HPV vaccine.

Some % do not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Characteristics Associated With Recommending HPV4 to 11- to 12-Year-Old Boys

On the basis of the bivariate analysis, the following variables were included in the multivariable analysis to determine characteristics associated with recommending HPV4 for 11- to 12-year-old boys: region of the country, urban versus rural location, proportion of patients aged 11 to 18 years, proportion of patients with private insurance, physicians’ gender, the 4 barrier scales, the susceptibility scale, the severity scale, physicians’ perception of HPV4 efficacy, and whether physicians routinely discussed sexual activity with 11- to 12-year-old boys (Table 3). Physicians were less likely to recommend HPV4 for their 11- to 12-year-old male patients if they practiced in a rural location and disagreed or didn’t know that HPV4 is efficacious for preventing genital warts in males. Physicians were more likely to recommend HPV4 if they routinely discuss sexual activity with 11- to 12-year-old boys and had higher scores on the scale measuring their perception of HPV severity.

Table 3.

Practice and Physician Characteristics Associated With Recommending the HPV4 Vaccine to 11- to 12-Year-Old Boys

| Characteristic | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Physician gender | ||

| Female | 1.28 (0.90–1.82) | |

| Male | Reference | |

| Region of country | ||

| Midwest | 0.74 (0.46–1.17) | |

| Northeast | 0.52 (0.31–0.88) | |

| West | 0.89 (0.56–1.41) | |

| South | Reference | |

| Practice location | ||

| Rural | 0.53 (0.33–0.87) | 0.50 (0.30–0.85) |

| Urban | Reference | Reference |

| Percentage of healthy children aged 11–18 in practice | ||

| 0–9% | 0.67 (0.42–1.06) | |

| 10–29% | 1.01 (0.68–1.49) | |

| ≥30% | Reference | |

| Percentage of patients with private insurance in practice | ||

| 0–24% | 1.45 (0.87–2.39) | |

| 25–74% | 1.20 (0.80–1.81) | |

| ≥75% | Reference | |

| Agree that HPV4 is efficacious for preventing genital warts in boys (physicians’ perception of benefit) | ||

| No or don’t know | 0.48 (0.31–0.74) | 0.57 (0.36–0.91) |

| Yes | Reference | Reference |

| Routinely discuss sexual activity with male patients 11–12 years old (cue to action) | ||

| Yes | 2.27 (1.55–3.32) | 2.24 (1.49–3.38) |

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Physicians’ perception of boys’ susceptibility to HPV scale (per increasing point) | 2.86 (2.03–4.02) | |

| Physicians’ perception of HPV severity scale (per increasing point) | 3.56 (2.46–5.16) | 3.29 (2.25–4.81) |

| Barriers | ||

| Vaccine financing issues scale (per increasing point) | 0.93 (0.75–1.14) | |

| Parental attitudes about HPV4 scale (per increasing point) | 0.80 (0.61–1.04) | |

| Logistic barriers to HPV4 administration scale (per increasing point) | 0.75 (0.57–0.97) | |

| Provider attitudes about the safety of HPV4 scale (per increasing point) | 0.62 (0.38–0.99) |

HPV = human papillomavirus; HPV4 = quadrivalent HPV vaccine; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

In a national survey conducted when HPV4 was permissively recommended for boys, we found that the majority of pediatricians and FM physicians thought that routine use of HPV4 in boys was justified to protect both boys and their future female partners; however, few physicians reported recommending or administering HPV4 to boys. Physicians who reported recommending HPV4 for 11- to 12-year-old boys were more likely to be from urban locations, perceive that HPV4 is efficacious, perceive that HPV-related disease is severe, and routinely discuss sexual health issues with 11- to 12-year-olds. Although the majority of physicians report that they would strongly recommend HPV4 for the subset of adolescent male subjects who are likely to have same-sex sexual encounters, they do not regularly ask about sexual orientation, making this sort of targeted vaccination strategy very unlikely to occur in practice.

In October 2011, on the basis of evidence of vaccine efficacy and safety, cost-effectiveness estimates (in the context of HPV vaccine coverage at 50% or less in girls16), and programmatic considerations, the ACIP changed its permissive recommendation to a stronger recommendation to include HPV4 in the routine immunization schedule for 11- to 12-year-old boys with catch-up vaccination of males aged 13 through 21 years.3 HPV4 was recommended at age 11 to 12 because it is most effective if provided before initiation of sexual activity and exposure to HPV,23,24 the antibody response to vaccine is better at this age compared to older adolescents,3 and because 2 additional vaccines, the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV) [this abbreviation is used later] and the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, are also recommended at this age.25 This recommendation is consistent with the current recommendation for girls.25

Our findings are similar to studies about health care providers’ willingness to recommend HPV4 to boys that were mainly conducted before the ACIP’s permissive recommendation.11–15,26,27 Despite the ACIP’s recommendation to administer HPV4 to boys at 11 to 12, physicians were more likely to strongly recommend it as their adolescent male patients’ age increased. HPV vaccine may have a role in promoting communication between providers, parents, and patients about sexual health issues28,29; however, a minority of physicians reported routinely discussing these issues with 11- to 12-year-olds for whom the HPV vaccine is recommended. Our finding that physicians who routinely discuss sexual health issues at 11 to 12 years were more likely to report recommending HPV4 to 11- to 12-year-old boys supports the idea that physicians are linking discussion of sexual health with a recommendation for the HPV vaccine. Physicians could discuss the HPV vaccine solely focusing on cancer prevention or bundled in a discussion of the other recommended adolescent vaccines. However, HPV4 for boys may be unique because physicians’ belief that prevention of cervical cancer in female partners is as important as preventing cancer in the male patient himself may make them think that they must discuss sex. Because early adolescents may look to their parents for guidance on preventive health care issues, discussions about the implications of HPV may be occurring more with parents of younger adolescents than with the adolescents themselves.30–32 Therefore, the perspectives of the parents are important.

Studies show that a health care provider’s recommendation is critical when adolescents and their parents are deciding whether to receive the HPV vaccine.26,33–35 We found that only 14% of physicians reported strongly recommending HPV4 to 11- to 12-year-old boys when it was permissively recommended by ACIP, and only 37% reported that they intended to strongly recommend HPV4 for 11- to 12-year-olds if the ACIP recommended HPV4 for routine immunization of boys. Although physicians’ reported strength of recommendation is a subjective measure, our data suggest that physicians may not be endorsing HPV4 for boys as strongly as they are for girls or for other recommended adolescent vaccines. National estimates suggest that 8.3% of adolescent boys received at least 1 dose of HPV4 in 2011.36 Data from 2012 will reveal whether the ACIP’s change from a permissive to a routine recommendation significantly increases boys’ receipt of HPV4.

Our study results suggest some interventions focused on primary care providers to increase HPV4 vaccination of boys. First, given that physicians are linking discussion of sexual health issues with recommending HPV4, primary care providers could benefit from evidence-based tools to help them communicate with parents and patients at different developmental stages about sexual health, including HPV vaccine. Second, because we found that physicians who perceived HPV-related disease to be severe and HPV4 to be efficacious were more likely to recommend HPV4, public health officials can continue to disseminate data about the severity of HPV-related diseases and the efficacy of HPV4 in preventing these diseases. At the time of our survey, data were strongest about the efficacy of HPV4 for prevention of genital warts in males. Since then, additional data have been published about the efficacy of HPV4 for prevention of anal cancer37 and the increasing incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal and esophageal cancers.38 Dissemination of this information may increase physicians’ perception of the importance of HPV4. Finally, because more physicians strongly recommended HPV4 at ages 16 to 18, public health officials could consider promoting catch-up vaccination of 16 year olds. A booster dose of MCV is now recommended at age 16 so these adolescents could be targeted for both MCV and HPV4.39

The perceived barriers to HPV4 administration for boys identified in this study are similar to barriers identified by other studies of adolescent vaccines.20,40–45 In all of these studies, vaccine financing issues were important barriers. The Affordable Care Act’s requirement that all nongrandfathered insurance plans must cover childhood vaccines is expected to alleviate some, but not all, of the financial barriers experienced by primary care providers. A commonly reported programmatic barrier is lack of office visits by adolescent patients. Because older adolescent boys are less likely to have an office visit than younger adolescent boys,46–48 catch-up vaccination of older boys could be particularly challenging. Finally, although only 11% of physicians reported concern about the safety of HPV4, this minority may undermine the perception of vaccine safety among many families.49

This study has important strengths and limitations. The surveyed physicians were shown in previous studies to be generally representative of physicians in the AAP and AAFP with respect to demographic and practice characteristics and locations throughout the United States.17 Although the response rate was high, the response was lower from FM physicians than pediatricians. Although the sample seemed representative, those who agreed to be surveyed might not have expressed similar views as those who chose not to be in the network and those who did not respond to the survey. Finally, physicians’ practices regarding HPV4 may have changed now that HPV4 is recommended for routine use in boys; however, it is unlikely that barriers to vaccine delivery, physicians’ knowledge and attitudes about HPV4, and physicians’ practices related to discussing sexual health have changed significantly without further intervention.

Conclusion

Continued evaluation will determine whether the recent recommendation to include HPV4 in the routine immunization schedule for boys will result in improved vaccine coverage. Primary care providers need support to implement effective systems, such as reminder-recall,50,51 to improve delivery of HPV and other adolescent vaccines at the 11- to 12-year-old preventive visit and at catch-up visits for older adolescents. In addition to the HPV vaccine, our findings could provide guidance for implementation of future adolescent vaccine recommendations. If other vaccines to prevent sexually transmitted infections are developed and recommended for adolescents, primary care physicians would benefit from clear, evidence-based guidance about how to discuss these vaccines with parents and with adolescents at different developmental stages. Our study suggests that when new adolescent vaccines become available, higher vaccine coverage—and ultimately prevention of disease—are more likely to be achieved if physicians are convinced that the diseases are severe and vaccines are efficacious, financial barriers are removed, and novel ways of reaching adolescents are utilized.

WHAT’S NEW.

Our survey findings suggest that primary care-focused interventions to improve human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination of boys should include tools to help providers communicate with parents and patients about HPV vaccine and sexual health, dissemination of data about HPV-related disease severity and vaccine efficacy, and promotion of catch-up vaccination at age 16.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynn Olson, PhD, and Karen O’Connor from the Department of Research, AAP, Herbert Young, MD, and Bellinda Schoof, MHA, at the AAFP, and the leaders of the AAP and AAFP for collaborating in the establishment of the sentinel networks in pediatrics and FM. We also thank all pediatricians and FM physicians in the networks for participating and responding to this survey. Supported in part by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PEP (MM-1040-08/08) through the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, DC. Presented in part at the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices meeting, October 27, 2010; Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, April 30, 2011; and at the National Immunization Conference, Washington, DC, March 30, 2011.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.Wilkin T, Lee JY, Lensing SY, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in HIV-1-infected men. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1246–1253. doi: 10.1086/656320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin-Hong PV, Palefsky JM. Natural history and clinical management of anal human papillomavirus disease in men and women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1127–1134. doi: 10.1086/344057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1705–1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saraiya M. Burden of HPV-associated cancers in the United States. Presentation before the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP); February 24, 2011; Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Accessed March 5, 2012]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb11/11-2-hpv-rela-cancer.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu D, Goldie S. The economic burden of noncervical human papillo-mavirus disease in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:500.e501–500.e507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoy T, Singhal PK, Willey VJ, et al. Assessing incidence and economic burden of genital warts with data from a US commercially insured population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2343–2351. doi: 10.1185/03007990903136378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palefsky JM. Human papillomavirus–related disease in men: not just a women’s issue. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4 suppl):S12–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin F, Prestage GP, Kippax SC, et al. Risk factors for genital and anal warts in a prospective cohort of HIV-negative homosexual men: the HIM study. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:488–493. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000245960.52668.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration. Approval letter—Gardasil (human papillomavirus quadrivalent [types 6, 11, 16, and 18]) Silver Spring, Md: Food and Drug Administration; 2011. [Accessed March 5, 2012]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm094042.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Tissot AM, et al. Factors influencing pediatricians’ intention to recommend human papillomavirus vaccines. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn JA, Zimet GD, Bernstein DI, et al. Pediatricians’ intention to administer human papillomavirus vaccine: the role of practice characteristics, knowledge, and attitudes. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riedesel JM, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, et al. Attitudes about human papillomavirus vaccine among family physicians. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daley MF, Liddon N, Crane LA, et al. A national survey of pediatrician knowledge and attitudes regarding human papillomavirus vaccination. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2280–2289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss TW, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination of males: attitudes and perceptions of physicians who vaccinate females. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 through 17 years—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1117–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crane LA, Daley MF, Barrow J, et al. Sentinel physician networks as a technique for rapid immunization policy surveys. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31:43–64. doi: 10.1177/0163278707311872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babbie E. The Practice of Social Research. 4. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janz N, Champion V, Strecher V. The Health Belief Model. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3. San Francisco, Calif: Wiley; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: a survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126:425–433. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sussman AL, Helitzer D, Sanders M, et al. HPV and cervical cancer prevention counseling with younger adolescents: implications for primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:298–304. doi: 10.1370/afm.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMahon SR, Iwamoto M, Massoudi MS, et al. Comparison of e-mail, fax, and postal surveys of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 pt 1):e299–e303. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed March 5, 2012];Statistical review and evaluation, anal cancer—Gardasil. 2010 Aug 30; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm094042.htm.

- 24.Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 5, 2012];Child and adolescent immunization schedules. 2012 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/schedules/child-schedule.htm.

- 26.Perkins RB, Clark JA. Providers’ attitudes toward human papilloma-virus vaccination in young men: challenges for implementation of 2011 recommendations. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6:320–323. doi: 10.1177/1557988312438911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL. HPV vaccine and males: issues and challenges. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117(2 suppl):S26–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broder KR, Cohn AC, Schwartz B, et al. Adolescent immunizations and other clinical preventive services: a needle and a hook? Pediatrics. 2008;121(suppl 1):S25–S34. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1115D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rupp R, Rosenthal SL, Middleman AB. Vaccination: an opportunity to enhance early adolescent preventative services. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:461–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rand CM, Humiston SG, Schaffer SJ, et al. Parent and adolescent perspectives about adolescent vaccine delivery: practical considerations for vaccine communication. Vaccine. 2011;29:7651–7658. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes CC, Jones AL, Feemster KA, et al. HPV vaccine decision making in pediatric primary care: a semi-structured interview study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexander AB, Stupiansky NW, Ott MA, et al. Parent–son decision-making about human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal SL, Weiss TW, Zimet GD, et al. Predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 19–26: importance of a physician’s recommendation. Vaccine. 2011;29:890–895. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilkey MB, Moss JL, McRee AL, et al. Do correlates of HPV vaccine initiation differ between adolescent boys and girls? Vaccine. 2012;30:5928–5934. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:671–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1576–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zandberg DP, Bhargava R, Badin S, et al. The role of human papillomavirus in nongenital cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:57–81. doi: 10.3322/caac.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dempsey A, Cohn L, Dalton V, et al. Patient and clinic factors associated with adolescent human papillomavirus vaccine utilization within a university-based health system. Vaccine. 2010;28:989–995. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dempsey AF, Davis MM. Overcoming barriers to adherence to HPV vaccination recommendations. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(17 suppl):S484–S491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ford CA, English A, Davenport AF, et al. Increasing adolescent vaccination: barriers and strategies in the context of policy, legal, and financial issues. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humiston SG, Albertin C, Schaffer S, et al. Health care provider attitudes and practices regarding adolescent immunizations: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oster NV, McPhillips-Tangum CA, Averhoff F, et al. Barriers to adolescent immunization: a survey of family physicians and pediatricians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:13–19. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ko EM, Missmer S, Johnson NR. Physician attitudes and practice toward human papillomavirus vaccination. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:339–345. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181dca59c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rand CM, Shone LP, Albertin C, et al. National health care visit patterns of adolescents: implications for delivery of new adolescent vaccines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:252–259. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nordin JD, Solberg LI, Parker ED. Adolescent primary care visit patterns. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:511–516. doi: 10.1370/afm.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dempsey AF, Freed GL. Health care utilization by adolescents on Medicaid: implications for delivering vaccines. Pediatrics. 2010;125:43–49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, et al. Sources and perceived credibility of vaccine-safety information for parents. Pediatrics. 2011;127(suppl 1):S107–S112. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1722P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suh CA, Saville A, Daley MF, et al. Effectiveness and net cost of reminder/recall for adolescent immunizations. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1437–e1445. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobson VJ, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD003941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]