Abstract

Background

Few studies have examined long-term changes in ethnoracial diversity for US states despite the potential social, economic, and political ramifications of such changes at the state level.

Objective

We describe shifts in diversity magnitude and structure from 1980 through 2015 to determine if states are following a universal upward path.

Methods

Decennial census data for 1980-2010 and American Community Survey data for 2015 are used to compute entropy index (E) and Simpson index (S) measures of diversity magnitude based on five panethnic populations. A typology characterizes the racial-ethnic structure of states.

Results

While initial diversity level and subsequent pace of change vary widely, every state has increased in diversity magnitude since 1980. A dramatic decline in the number of predominantly White states has been accompanied by the rise of states with multigroup structures that include Hispanics. These diverse states are concentrated along the coasts and across the southern tier of the nation. Differences in panethnic population growth (especially rapid Hispanic and Asian growth coupled with white stability) drive the diversification trend.

Conclusions

The diversity hierarchy among states has remained relatively stable over the past 35 years in the face of universal gains in diversity magnitude and the increasing heterogeneity of racial-ethnic structures.

Contribution

We document ethnoracial diversity patterns at an understudied geographic scale where diversity may have important consequences across a range of institutional domains.

1. Introduction

Racial and ethnic diversity has risen dramatically in the United States since 1980. Due to the strength of immigration, higher fertility, youthful age structures, and other demographic forces fueling minority gains, people of color are now projected to surpass whites in number before mid-century (Colby and Ortman 2015; Frey 2015; Lichter 2013). This diversification trend could be particularly consequential at the state level. For example, diversity has already boosted the influence of Democrat-leaning minorities in battleground states, and it may have a larger impact in the future as more Hispanics and Asians become eligible to vote (Frey 2015). Hero and Tolbert (1996) have shown that black educational and health outcomes are better in ethnoracially diverse states than in predominantly white ones. Other work documents complex yet significant relationships between the representation of blacks, Hispanics, and immigrants and public spending and welfare benefits across states (Fox, Bloemraad, and Kesler 2013; Gais and Weaver 2002; Matsubayashi and Rocha 2012). Higher diversity can also blur color lines within states by increasing rates of intermarriage and multiracial self-identification (Lee and Bean 2010).

Despite such consequences, far more attention has been devoted to the ethnoracial diversity of metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas, places, and neighborhoods (Farrell and Lee 2011; Hall, Tach, and Lee 2016; Logan and Zhang 2010; Parisi, Lichter, and Taquino 2015) than of states. The scant literature on state diversity that exists often fails to conceptualize diversity in careful fashion or to track it over an extended period (Arreola 2004; Brewer and Suchan 2001; Bump, Lowell, and Pettersen 2005; for an exception, see Wright et al. 2014). We address the first of these shortcomings by distinguishing between two dimensions of diversity often studied at other spatial scales (Clark et al. 2015; Holloway, Wright, and Ellis 2012; Lee, Iceland, and Farrell 2014). The magnitude dimension captures the number of ethnoracial categories in a population and their relative sizes: The more evenly persons are spread across categories, the higher the magnitude or level of diversity will be. The second dimension, which we term racial-ethnic structure, refers to the specific groups present. Realizing that combinations of different groups can yield identical diversity levels underscores the value of taking structure into account. To provide a fuller longitudinal perspective on diversity, we measure changes in magnitude and structure from 1980 through 2015. Our analysis evaluates to what extent American states have followed a universal path toward more diverse, multigroup compositions over the past 35 years.

2. Data and Measures

We have extracted state data from the summary files of the 1980 through 2010 decennial censuses and the 2015 American Community Survey. The crosstabulation of race with Hispanic origin yields counts of Hispanics of any race and of non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Asians, Pacific Islanders, Native Americans (American Indians and Alaska Natives), multiracial individuals, and those reporting some other race. We combine Asians and Pacific Islanders, hereafter labeled Asian. Small numbers justify the creation of an ‘other’ category comprising Native Americans and multiracial and other-race persons. These adjustments produce five panethnic populations - Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Asians, and ‘others’ - that are exhaustive, mutually exclusive, and largely comparable over time. The less than perfect comparability results from a change in the census questionnaire, introduced in 2000, that allows respondents to self-identify as belonging to multiple races. Because the addition of the multirace option has more than doubled the size of the still-small ‘other’ category in most states (with Hawaii experiencing the biggest gain), diversity receives a minor boost between 1990 and 2000 but overall patterns (trend lines, differences among states, etc.) are minimally affected (see Lee and Hughes 2015).

We tap diversity magnitude with the entropy index, symbolized by E, which is a building block of the information theory index H, a multigroup measure of segregation (Reardon and Firebaugh 2002; Theil 1972). Formally,

where pr refers to ethnoracial category r's proportion of the population in a given state and R signifies the number of such categories. The entropy index reaches maximum value (the natural log of R) when all ethnoracial categories are the same size. To standardize E, we divide it by its maximum (1.609 for five panethnic groups) then multiply by 100. The resulting E scores theoretically range from 0 or complete homogeneity (when all residents of a state belong to the same group) to 100 or complete heterogeneity, with each of the five groups containing one-fifth of a state's residents. We occasionally turn to the Simpson interaction index (or S), another diversity measure that is highly correlated with E (zero-order r > .98 across states). This index estimates the probability that two people randomly selected from the same state will be members of different panethnic categories.

To capture the structural dimension of diversity, we supplement the entropy index with tabular distributions that communicate the proportions of whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and ‘others’ anchoring particular diversity magnitudes. The same purpose is served by a typology of racial-ethnic structure for the 50 states, developed in a later section. Note that Washington, DC is excluded from our analysis. Although its population exceeds that of Vermont and Wyoming, the District of Columbia differs from states in important ways: it consists of a single, densely settled municipality with no governor or legislature and no voting representation in Congress. When studying ethnoracial diversity, we believe that Washington, DC is more appropriately compared with other principal cities or metropolitan areas (as in Fowler, Lee and Matthews 2016; Friedman et al. 2005).

3. Results

3.1 Diversity Trends

Table 1 lists states in order of their 2015 diversity magnitude. Hawaii and California, the most diverse, exhibit Es of 82.6 and 80.2 respectively. In terms of individual probabilities (Simpson S scores), two randomly selected Hawaiians or Californians would be members of different ethnoracial groups nearly 70% of the time. Other top 10 states in 2015 include the traditional immigrant destinations of New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida along with a few newer destinations (Nevada, Maryland, Georgia) and Alaska. The bottom of the list is occupied by Maine, Vermont, West Virginia, and New Hampshire. In these four states, the corresponding S values indicate no more than a one in six chance of two randomly drawn residents belonging to different groups. States in the Midwest and Mountain West are also over-represented among the less diverse.

Table 1. Panethnic Diversity by State, 1980-2015.

| 2015 Rank | E Score | 2015-1980 Difference | Rank Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| State | 2015 | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 | 1980 | |||

| US Total | 70.23 | 67.54 | 61.20 | 50.75 | 44.27 | 25.96 | N/A | |

| 1 | Hawaii | 82.61 | 80.06 | 78.07 | 61.47 | 65.29 | 17.32 | 0 |

| 2 | California | 80.17 | 79.41 | 78.05 | 69.15 | 62.13 | 18.03 | 1 |

| 3 | Nevada | 78.23 | 74.97 | 64.97 | 47.71 | 40.80 | 37.43 | 14 |

| 4 | New York | 75.86 | 73.25 | 69.54 | 58.18 | 50.44 | 25.42 | 2 |

| 5 | New Jersey | 75.32 | 72.23 | 65.10 | 52.33 | 44.16 | 31.17 | 8 |

| 6 | Maryland | 75.12 | 71.39 | 61.74 | 50.54 | 44.40 | 30.72 | 6 |

| 7 | Texas | 74.50 | 72.71 | 69.08 | 62.03 | 57.57 | 16.94 | -3 |

| 8 | Florida | 71.04 | 68.83 | 62.06 | 50.96 | 46.04 | 25.00 | 1 |

| 9 | Georgia | 70.13 | 67.74 | 58.98 | 45.69 | 42.36 | 27.76 | 6 |

| 10 | Alaska | 69.39 | 65.50 | 60.49 | 53.80 | 48.72 | 20.67 | -3 |

| 11 | Virginia | 69.14 | 65.56 | 56.63 | 45.08 | 40.22 | 28.92 | 8 |

| 12 | Illinois | 68.70 | 66.30 | 61.10 | 49.90 | 44.85 | 23.86 | -1 |

| 13 | Arizona | 68.59 | 66.44 | 61.07 | 54.07 | 50.54 | 18.06 | -8 |

| 14 | New Mexico | 67.80 | 67.26 | 66.93 | 64.48 | 62.88 | 4.92 | -12 |

| 15 | Delaware | 66.15 | 62.85 | 52.46 | 40.34 | 36.44 | 29.71 | 7 |

| 16 | Oklahoma | 65.28 | 62.48 | 54.81 | 44.03 | 36.63 | 28.64 | 5 |

| 17 | North Carolina | 64.92 | 62.33 | 54.05 | 42.93 | 41.36 | 23.56 | -1 |

| 18 | Connecticut | 62.46 | 58.44 | 49.75 | 37.71 | 30.00 | 32.47 | 8 |

| 19 | Washington | 62.45 | 58.64 | 49.52 | 35.23 | 28.39 | 34.06 | 8 |

| 20 | Louisiana | 61.19 | 58.90 | 53.84 | 49.15 | 47.54 | 13.64 | -12 |

| 21 | South Carolina | 58.75 | 57.39 | 50.90 | 43.95 | 43.99 | 14.76 | -7 |

| 22 | Colorado | 57.94 | 55.83 | 51.00 | 41.74 | 38.50 | 19.44 | -2 |

| 23 | Massachusetts | 57.84 | 53.53 | 44.36 | 32.15 | 22.53 | 35.31 | 10 |

| 24 | Mississippi | 55.90 | 55.07 | 50.40 | 45.65 | 45.71 | 10.20 | -14 |

| 25 | Rhode Island | 55.54 | 51.64 | 43.49 | 29.39 | 20.17 | 35.37 | 13 |

| 26 | Alabama | 55.47 | 54.11 | 47.41 | 40.81 | 40.26 | 15.20 | -8 |

| 27 | Arkansas | 54.09 | 51.57 | 43.61 | 34.11 | 33.43 | 20.65 | -3 |

| 28 | Michigan | 52.27 | 49.80 | 45.74 | 37.18 | 34.01 | 18.27 | -5 |

| 29 | Kansas | 52.04 | 49.23 | 41.36 | 30.56 | 26.00 | 26.04 | 1 |

| 30 | Tennessee | 51.41 | 48.67 | 41.42 | 32.91 | 31.90 | 19.52 | -5 |

| 31 | Oregon | 50.84 | 47.89 | 40.35 | 26.56 | 20.95 | 29.89 | 5 |

| 32 | Pennsylvania | 50.53 | 46.50 | 37.75 | 29.25 | 25.87 | 24.66 | -1 |

| 33 | Minnesota | 46.56 | 42.70 | 32.75 | 19.81 | 13.53 | 33.03 | 12 |

| 34 | Indiana | 46.34 | 43.04 | 34.73 | 25.94 | 24.34 | 21.99 | -2 |

| 35 | Nebraska | 45.82 | 42.44 | 33.40 | 22.07 | 18.44 | 27.38 | 7 |

| 36 | Missouri | 45.35 | 43.07 | 37.18 | 29.48 | 27.67 | 17.68 | -8 |

| 37 | Ohio | 45.29 | 42.30 | 36.37 | 29.09 | 26.80 | 18.50 | -8 |

| 38 | Utah | 45.15 | 42.71 | 35.56 | 24.71 | 22.04 | 23.11 | -3 |

| 39 | Wisconsin | 44.17 | 41.29 | 33.67 | 24.55 | 18.95 | 25.22 | 1 |

| 40 | South Dakota | 39.66 | 35.60 | 28.33 | 22.22 | 19.59 | 20.07 | -1 |

| 41 | Idaho | 38.21 | 36.16 | 29.64 | 21.49 | 18.08 | 20.13 | 2 |

| 42 | Kentucky | 36.94 | 34.44 | 27.66 | 20.79 | 20.58 | 16.36 | -5 |

| 43 | Wyoming | 36.79 | 33.81 | 28.71 | 24.47 | 22.17 | 14.62 | -9 |

| 44 | North Dakota | 35.66 | 28.98 | 22.33 | 17.25 | 13.95 | 21.71 | 0 |

| 45 | Iowa | 34.99 | 31.01 | 22.44 | 13.70 | 11.00 | 23.99 | 2 |

| 46 | Montana | 32.29 | 29.68 | 26.02 | 21.83 | 18.47 | 13.81 | -5 |

| 47 | New Hampshire | 26.39 | 23.23 | 16.23 | 9.80 | 6.57 | 19.82 | 2 |

| 48 | West Virginia | 22.75 | 20.71 | 16.93 | 12.85 | 13.43 | 9.32 | -2 |

| 49 | Vermont | 20.63 | 18.31 | 13.23 | 7.36 | 5.98 | 14.65 | 1 |

| 50 | Maine | 19.95 | 18.02 | 12.25 | 7.81 | 6.62 | 13.33 | -2 |

| Mean | 54.49 | 51.68 | 45.07 | 35.88 | 32.25 | 22.25 | ||

| Std. Dev. | 16.08 | 16.26 | 16.60 | 15.42 | 15.16 | 7.30 | ||

| Minimum | 19.95 | 18.02 | 12.25 | 7.36 | 5.98 | 4.92 | ||

| Maximum | 82.61 | 80.06 | 78.07 | 69.15 | 65.29 | 37.43 | ||

| Range | 62.66 | 62.04 | 65.82 | 61.78 | 59.31 | 32.51 | ||

The rest of Table 1 offers several key lessons about ethnoracial diversification. First, states differ markedly in diversity magnitude at all five time points, spanning a 60-65 point range. Second, diversity change has been relentlessly positive, with only four decade- and state-specific declines in E. Another lesson is about variation in the extent of change (sixth column). Nevada has become the third most diverse state by virtue of its 37-point jump in E. Yet the E score for New Mexico - the second most diverse state in 1980 - has increased less than five points during the subsequent 35 years. Only one other state, West Virginia, undergoes a single-digit diversity gain.

We highlight the variation in diversity change by comparing 15 ‘big gainer’ states (including Nevada, Massachusetts, Washington, New Jersey, Virginia, and Georgia, among others) with 18 ‘small gainer’ states (such as Michigan, California, Hawaii, Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama). The former have 1980 to 2015 increases in E of 25.75 points or more, roughly half a standard deviation above the overall mean change; the latter exhibit increases of less than 18.75, half a deviation below the mean. What stands out about the big gainers is the expansion of their foreign-born populations, which grow on average by an impressive 358% during the study period. Foreign-born growth, which is 22 times greater than mean white growth, primarily reflects a combination of state-specific Hispanic immigration and subsequent domestic migration, as documented in previous research (Johnson and Lichter 2008); natural increase drives Hispanic but not foreign-born growth. These demographic dynamics have altered the racial-ethnic composition of the big gainer states; ten were majority white in 1980 but none are now. By contrast, average foreign-born growth for small gainer states (190%) falls well short of that for their big gainer counterparts. Consistent with a ceiling effect, several of these small gainers were already highly diverse in 1980 but have experienced modest increases thereafter (e.g., Hawaii, California, Texas, and Arizona in addition to New Mexico).

Shifts in the rank order of diversity magnitude since 1980 (seventh column of Table 1) are dominated by a handful of ‘winners’ (Nevada, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Massachusetts) and ‘losers’ (New Mexico, Louisiana, Mississippi).The winners have much higher Hispanic and Asian growth rates than the losers, although the combination of such growth with relatively stagnant foreign-born populations in Rhode Island and Massachusetts points to the importance of higher fertility in the Hispanic and Asian second generations and beyond. For the most part, however, the shifts appear moderate, 29 states climbing or falling by five places or less. The diversity hierarchy - where states stand in relation to each other - has remained rather stable, as attested by a Spearman r of .90 between their 1980 and 2015 ranks. Line graphs that reveal the approximately parallel nature of the diversity trajectories for all 50 states (not shown) further support the notion of relative stability.

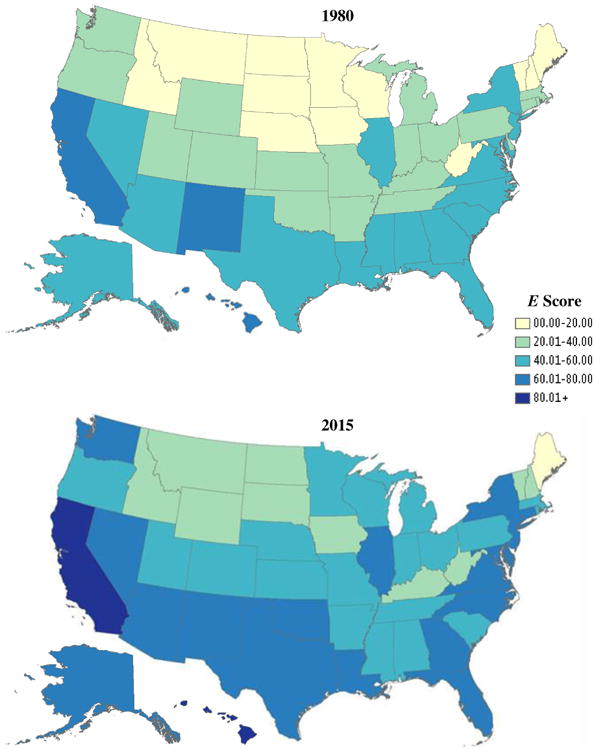

We have created 1980 and 2015 choropleth maps that display states based on constant 20-point increments in their entropy index values (Figure 1). The maps show that the diversity landscape of the nation has been transformed. Of the 12 low-diversity states (E< 20) dominating the northern tier over three decades ago, only Maine is still that homogeneous. By contrast, the number of higher-diversity states (E> 60) has increased from 3 (Hawaii, California, New Mexico) to 20, 8 of which exceed the magnitude of diversity for the US as a whole. These 20 form a rough U shape from the Pacific through the Southwest and up the Atlantic seaboard. At the scale of states, diversity now constitutes a bicoastal, southern-tier phenomenon.

Figure 1.

State Panethnic Diversity, 1980 and 2015

3.2 Differences in Racial-Ethnic Structure

States with high diversity magnitudes do not always resemble each other in racial-ethnic structure. Thus, an important task is to determine whether a few broadly applicable types of structure can be discerned. We have tried cluster analysis, using hierarchical agglomerative procedures to form the clusters, but the results proved unsatisfactory. However, a simpler strategy achieves the desired objective. This strategy acknowledges that whites remain ubiquitous, composing a majority or plurality in 46 states. To define types of racial-ethnic structure, we therefore start with white representation then add each minority group that constitutes 10% or more of the state population. When a minority group reaches this threshold, its members have visibility ‘on the ground’ and are more likely to be recognized as a meaningful constituency in politics, education, the economy, and other institutional settings. The 10% threshold also approximates the average representation of the four minorities of interest in the 2015 (9.6%)and 2000 (9.0%) national populations, and it has been used to establish group presence in previous studies of community diversity and ethnoracial composition (e.g., Farrell and Lee 2011; Walton and Hardebeck 2016)).

Employing the 10% criterion, we have classified the 2015 racial-ethnic structures of states into six types. The three most common types include 39 states and reflect the enduring influence of white, black, and Hispanic historical settlement patterns. The top panel of Table 2 lists largely White states in which no minority group equals or exceeds one-tenth of the population and whites make up four-fifths or more. Most of these states are located in the Midwest or New England - regions first settled by European immigrants - and several have small populations. Southern states predominate in the White-Black category, where blacks are the lone minority of any size and have long been concentrated. Hispanics average 16% of the population in White-Hispanic states. Seven of the 12 states displaying this structure fall in the West region, close to Mexico, and the three in the Northeast (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island) attract people from the Caribbean and other Latin American origins.

Table 2. Type of State Panethnic Structure, 2015.

| Type of Structure | % of State Population | 2015 E Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Other | ||

| White | ||||||

| Average | 86.78 | 3.57 | 4.35 | 1.85 | 3.46 | 33.62 |

| Minnesota | 80.91 | 5.70 | 5.14 | 4.71 | 3.54 | 46.56 |

| Indiana | 79.90 | 9.01 | 6.63 | 2.11 | 2.35 | 46.34 |

| Wisconsin | 81.81 | 6.19 | 6.60 | 2.70 | 2.69 | 44.17 |

| Kentucky | 85.15 | 7.94 | 3.30 | 1.40 | 2.21 | 36.94 |

| Wyoming | 84.06 | 0.80 | 9.87 | 0.87 | 4.40 | 36.79 |

| North Dakota | 85.91 | 2.03 | 3.44 | 1.34 | 7.27 | 35.66 |

| Iowa | 86.77 | 3.34 | 5.58 | 2.28 | 2.04 | 34.99 |

| Montana | 86.60 | 0.42 | 3.61 | 0.94 | 8.44 | 32.29 |

| New Hampshire | 90.94 | 1.39 | 3.33 | 2.56 | 1.78 | 26.39 |

| West Virginia | 92.30 | 3.77 | 1.45 | 0.79 | 1.69 | 22.75 |

| Vermont | 93.42 | 1.23 | 1.66 | 1.42 | 2.26 | 20.63 |

| Maine | 93.58 | 1.04 | 1.52 | 1.03 | 2.83 | 19.95 |

| White-Black | ||||||

| Average | 66.66 | 21.68 | 6.28 | 2.81 | 2.58 | 58.38 |

| Maryland | 51.86 | 29.03 | 9.53 | 6.41 | 3.17 | 75.12 |

| Georgia | 53.67 | 30.93 | 9.30 | 3.79 | 2.30 | 70.13 |

| Virginia | 62.50 | 18.88 | 8.99 | 6.26 | 3.37 | 69.14 |

| Delaware | 63.05 | 21.19 | 9.02 | 3.83 | 2.92 | 66.15 |

| North Carolina | 63.61 | 21.33 | 9.08 | 2.68 | 3.31 | 64.92 |

| Louisiana | 58.98 | 31.94 | 4.89 | 1.74 | 2.44 | 61.19 |

| South Carolina | 63.72 | 27.20 | 5.36 | 1.50 | 2.22 | 58.75 |

| Mississippi | 56.98 | 37.64 | 2.87 | 1.05 | 1.47 | 55.90 |

| Alabama | 65.94 | 26.69 | 3.97 | 1.27 | 2.14 | 55.47 |

| Arkansas | 73.03 | 15.66 | 6.98 | 1.66 | 2.67 | 54.09 |

| Michigan | 75.45 | 13.74 | 4.90 | 2.98 | 2.94 | 52.27 |

| Tennessee | 74.24 | 16.68 | 5.05 | 1.65 | 2.38 | 51.41 |

| Pennsylvania | 77.26 | 10.54 | 6.80 | 3.28 | 2.13 | 50.53 |

| Missouri | 79.87 | 11.58 | 3.95 | 1.96 | 2.63 | 45.35 |

| Ohio | 79.70 | 12.14 | 3.54 | 2.03 | 2.60 | 45.29 |

| White-Hispanic | ||||||

| Average | 71.10 | 4.64 | 16.16 | 4.25 | 3.48 | 56.26 |

| Nevada | 50.53 | 8.18 | 28.14 | 8.46 | 4.69 | 78.23 |

| Arizona | 55.69 | 4.14 | 30.73 | 3.23 | 6.21 | 68.59 |

| Connecticut | 67.94 | 9.90 | 15.42 | 4.35 | 2.39 | 62.46 |

| Washington | 69.69 | 3.53 | 12.36 | 8.50 | 5.92 | 62.45 |

| Colorado | 68.49 | 3.91 | 21.34 | 3.06 | 3.20 | 57.94 |

| Massachusetts | 72.98 | 6.77 | 11.16 | 6.32 | 2.78 | 57.84 |

| Rhode Island | 73.38 | 5.43 | 14.40 | 3.34 | 3.44 | 55.54 |

| Kansas | 76.37 | 5.78 | 11.55 | 2.89 | 3.41 | 52.04 |

| Oregon | 76.51 | 1.82 | 12.71 | 4.37 | 4.60 | 50.84 |

| Nebraska | 80.06 | 4.66 | 10.39 | 2.13 | 2.77 | 45.82 |

| Utah | 78.91 | 1.08 | 13.66 | 3.06 | 3.28 | 45.15 |

| Idaho | 82.60 | 0.53 | 12.08 | 1.33 | 3.45 | 38.21 |

| White-Other | ||||||

| Average | 70.15 | 4.01 | 6.89 | 3.53 | 15.42 | 58.11 |

| Alaska | 61.27 | 3.35 | 7.02 | 7.05 | 21.30 | 69.39 |

| Oklahoma | 66.41 | 7.18 | 10.14 | 2.08 | 14.20 | 65.28 |

| South Dakota | 82.78 | 1.49 | 3.50 | 1.47 | 10.75 | 39.66 |

| White-Hispanic-Black | ||||||

| Average | 54.34 | 13.67 | 23.74 | 6.07 | 2.18 | 73.09 |

| New York | 55.82 | 14.38 | 18.82 | 8.41 | 2.57 | 75.86 |

| New Jersey | 56.05 | 12.66 | 19.67 | 9.43 | 2.19 | 75.32 |

| Texas | 42.94 | 11.68 | 38.85 | 4.57 | 1.96 | 74.50 |

| Florida | 55.11 | 15.52 | 24.48 | 2.68 | 2.21 | 71.04 |

| Illinois | 61.81 | 14.10 | 16.89 | 5.23 | 1.97 | 68.70 |

| Minority Plurality | ||||||

| Average | 32.97 | 3.17 | 32.40 | 20.21 | 11.25 | 76.86 |

| Hawaii | 22.78 | 1.92 | 10.39 | 44.91 | 20.00 | 82.61 |

| California | 37.85 | 5.60 | 38.79 | 14.36 | 3.40 | 80.17 |

| New Mexico | 38.28 | 1.99 | 48.02 | 1.36 | 10.35 | 67.80 |

The three remaining types capture more complex or unusual racial-ethnic structures. Alaska, Oklahoma, and South Dakota, the only White-Other states, stand out because of their disproportionate shares of Native Americans. Five immigrant gateway states qualify as White-Black-Hispanic. Whites are always a majority or plurality in New York, Texas, New Jersey, Florida, and Illinois, followed by Hispanics and then blacks. The final, Minority Plurality category includes three states where a minority group constitutes the plurality. Exhibiting a distinctive four-group structure, Hawaii is the only state in which Asians are the largest panethnic population. Whites hold a slim advantage over ‘others’ (mainly multiracial persons) as the second biggest group, and Hispanics now make up one-tenth of all Hawaii residents. In both California and New Mexico, Hispanic pluralities exceed the representation of whites but the third group achieving the 10% threshold differs: Asians in California, ‘others’ (primarily Native Americans) in New Mexico.

Diversity magnitude differs across the six types of structure. The mean 2015 E is lowest for the White states (33.6) and highest for the Minority Plurality (76.9) and White-Hispanic-Black (73.1) states. Expressed in S values, two persons chosen at random from the pooled population of the White states are likely to belong to different panethnic groups 26% of the time, versus 61% of the time for two residents drawn from the White-Hispanic-Black states. But significant variation in diversity is apparent within most structural categories. Aside from the Minority Plurality and White-Hispanic-Black categories, a gap of 25 to 40 points separates the most and least diverse states that display each type of structure.

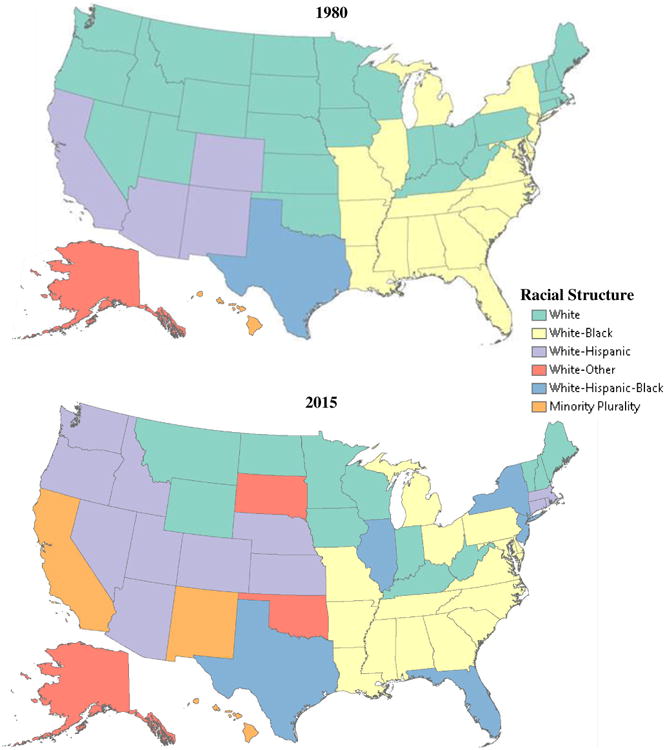

Comparing the 2015 snapshot in Table 2 with its 1980 counterpart reveals a major decline in the predominantly White category. As Figure 2 conveys, the number of White states has shrunk from 26 to 12 between 1980 and 2015. The White-Black category remains fairly stable, contracting from 17 states to 15. On the plus side, White-Hispanic states have tripled in number (from 4 to 12), and Texas - the lone White-Hispanic-Black state in 1980 - is joined by four others 35 years later. States with a Minority Plurality or White-Other composition increase from two to six. Variations in group-specific growth are responsible for this shifting map. White-Hispanic states, for instance, are distinguished by their relatively high white growth (mean 36% increase over the 35-year period) coupled with striking Hispanic (571%) and Asian (674%) increases. On the other hand, White-Black-Hispanic and Minority Plurality states exhibit lower black and Hispanic growth than the four other structural types, yet the White-Black-Hispanic states boast the highest average Asian growth.

Figure 2.

State Panethnic Structure, 1980 and 2015

Such differences between structural types, though interesting, should not obscure our broader finding: that a transition from single-group to multigroup structures has taken place in which Hispanics figure prominently. The demographic dynamics of the transition are remarkably similar from state to state, in direction if not magnitude. Every minority group and the foreign-born population as a whole have increased in size in every state since 1980, and three states - California, New Mexico, and Texas - have attained minority-majority status. (A fourth, Hawaii, has long been minority-majority.) Across states the mean 1980-2015 Hispanic increase of 510%, though exceeded by Asian growth (607%), operates on a much larger 1980 base population. Thus, the mean gain in Hispanics almost triples the gain for Asians and more than quintuples that of the ‘other’ category. The black population, with modest 133% growth, also pales in comparison to Hispanics' average gains. Finally, whites' stagnant growth of 18% between 1980 and 2015 (including absolute declines in 14 states), accompanied by the impressive gains for most minorities, guarantees pervasive changes in the state-level representation of panethnic populations over time. An across-the-board decline in the percentage of whites has been offset by increasing Hispanic and ‘other’ shares in all 50 states, increasing Asian shares in 49, and increasing black shares in 46.

4. Conclusion

Taken together, our findings suggest an affirmative answer to the question posed by the paper's title. All states are more racially and ethnically diverse now than they were 35 years ago, following parallel but not identical trajectories since 1980. This parallelism produces a relatively stable diversity hierarchy over time: changes in how states rank in relation to each other in magnitude have been minor. A common pattern can be discerned for diversity structure as well. Specifically, the number of White-Black states has remained constant while initially White states and some multigroup ones have transitioned to more complex ethnoracial compositions. Driving such transitions are minimal white growth (or decline) combined with substantial population gains for most minority groups, especially their foreign-born segments. The central roles played by Hispanics and, to a lesser extent, Asians reflect a combination of demographic mechanisms, including young age structures, high rates of natural increase, and immigration and domestic migration to a wider range of destination states than in the past. Simply put, the rise in state diversity is largely a function of the demographic ‘success’ of these immigrant-rich panethnic populations.

We recognize that ethnoracial diversity is relevant to policy at more local scales (e.g., metropolitan areas, communities) and that residents' allegiances often lie there. Yet state-level diversity patterns remain important in their own right because of their real-world consequences. Consider, for example, the outcome of the 2016 US presidential election. The percentage of a state's registered voters selecting Democrat Hillary Clinton exhibits a zero-order Pearson r of .51 with the 2015 E scores in Table 1, and that correlation increases to .64 when two outliers (homogeneous but liberal Vermont and heterogeneous but conservative Oklahoma) are excluded. Moreover, the correlation remains significant after adjusting separately for percent black (partial r = .64) and percent Hispanic (partial r = .55). This suggests that diversity proper – the extent of equality in group size – matters in addition to the shares of particular minority groups, countering an important criticism of entropy-style indexes (see Abascal and Baldassarri 2015). Future research should continue to refine the conceptualization and measurement of diversity. It should also look beyond the electoral college, exploring the implications of ethnoracial diversity magnitude and structure for the economy, education, social services, and other institutional domains where states constitute salient geographies.

Footnotes

Support for this research has been provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD074605, PI Barrett Lee). Additional support comes from the Penn State Population Research Institute, which receives infrastructure funding from NICHHD (P2CHD041025). The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Barrett A. Lee, Department of Sociology and Population Research Institute, The Pennsylvania State University

Michael J.R. Martin, Department of Sociology and Population Research Institute, The Pennsylvania State University

Stephen A. Matthews, Department of Sociology and Population Research Institute, The Pennsylvania State University

Chad R. Farrell, Department of Sociology, University of Alaska-Anchorage

References

- Abascal M, Baldassarri D. Love thy neighbor? Ethnoracial diversity and trust reexamined. American Journal of Sociology. 2015;121(3):722–782. doi: 10.1086/683144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola DD. Hispanic American legacy, Latino diaspora. In: Arreola DD, editor. Hispanic spaces, Latino places: Community and cultural diversity in contemporary America. Austin: University of Texas Press; 2004. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer CA, Suchan TA. Mapping census 2000: The geography of US diversity. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2001. US Census Bureau, Census Special Reports, Series CENSR/01-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bump MN, Lindsay Lowell B, Pettersen S. The growth and population characteristics of immigrants and minorities in America's new settlement states. In: Gozdziak EM, Martin SF, editors. Beyond the gateway: Immigrants in a changing America. Lanham: Lexington Books; 2005. pp. 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WAV, Anderson E, Osth J, Malmberg B. A multiscalar analysis of neighborhood composition in Los Angeles: A location-based approach to segregation and diversity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2015;105(6):1260–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060; pp. P25–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell CR, Lee BA. Racial diversity and change in metropolitan neighborhoods. Social Science Research. 2011;40(4):1108–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C, Lee BA, Matthews SA. The contribution of places to metropolitan ethnoracial diversity and segregation: Decomposing change across time and space. Demography. 2016;53(6):1955–1977. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0517-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C, Bloemraad I, Kesler C. Immigration and redistributive social policy. In: Card D, Raphael S, editors. Immigration, poverty, and socioeconomic inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2013. pp. 381–420. [Google Scholar]

- Frey WH. Diversity explosion: How new racial demographics are remaking America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Price M, Singer A, Cheung I. Race, immigrants, and residence: A new racial geography of Washington, DC. Geographical Review. 2005;95(2):210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gais T, Weaver RK. State policy choices under welfare reform. In: Sawhill IV, Weaver RK, Haskins R, Kane A, editors. Welfare reform and beyond: The future of the safety net. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2002. pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Tach L, Lee BA. Trajectories of ethnoracial diversity in American communities, 1980-2010. Population and Development Review. 2016;42(2):271–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hero RE, Tolbert CJ. A racial/ethnic diversity interpretation of politics and policy in the U.S. American Journal of Political Science. 1996;40(3):851–871. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SR, Wright R, Ellis M. The racially fragmented city? Neighborhood racial segregation and diversity jointly considered. Professional Geographer. 2011;63(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BA, Hughes L. Bucking the trend: Is ethnoracial diversity declining in American communities? Population Research and Policy Review. 2015;34(1):113–139. doi: 10.1007/s11113-014-9343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BA, Iceland J, Farrell CR. Is ethnoracial residential integration on the rise? Evidence from metropolitan and micropolitan America since 1980. In: Logan JR, editor. Diversity and disparities: America enters a new century. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2014. pp. 415–456. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Bean FD. The diversity paradox: Immigration and the color line in twenty-first century America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT. Integration or fragmentation? Racial diversity and the American future. Demography. 2013;50(2):359–91. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Zhang C. Global neighborhoods: New pathways to diversity and separation. American Journal of Sociology. 2010;115(4):1069–1109. doi: 10.1086/649498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi T, Rocha RR. Racial diversity and public policy in the states. Political Research Quarterly. 2012;65(3):600–614. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi D, Lichter DT, Taquino MC. The buffering hypothesis: Growing diversity and declining black-white segregation in America's cities, suburbs, and small towns? Sociological Science. 2015;2(March):125–157. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF, Firebaugh G. Measures of multigroup segregation. Sociological Methodology. 2002;32(1):33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Theil H. Statistical decomposition analysis: With applications in the social and administrative sciences. Amsterdam: North-Holland: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Walton E, Hardebeck M. Multiethnic neighborhoods on the ground: Resources, constraints, and sense of community. Du Bois Review. 2016;13(2):345–363. [Google Scholar]

- Wright RA, Ellis M, Holloway SR, Wong S. Patterns of racial diversity and segregation in the United States: 1990-2010. Professional Geographer. 2014;66(2):173–182. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2012.735924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]