Abstract

Purpose

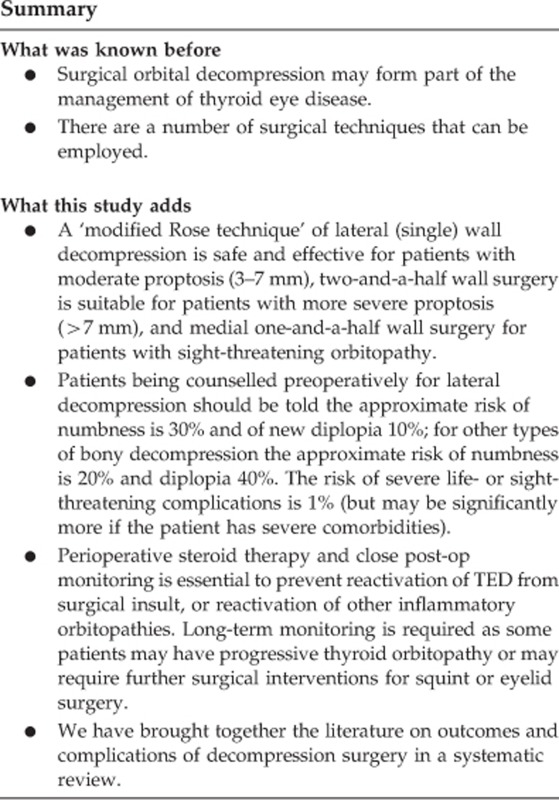

To determine the safety and effectiveness of orbital decompression for thyroid eye disease (TED) in our unit. To put this in the context of previously published literature.

Patients and methods

A retrospective case review of all patients undergoing orbital decompression for TED under the care of one orbital surgeon (SMS) between January 2009 and December 2015. A systematic literature review of orbital decompression for TED.

Results

Within the reviewed period, 93 orbits of 55 patients underwent decompression surgery for TED. There were 61 lateral (single) wall decompressions, 17 medial one-and-a-half wall, 11 two-and-a-half wall, 2 balanced two wall, and 2 orbital fat only decompressions. For the lateral (single) wall decompressions, mean reduction in exophthalmometry (95% confidence interval (CI) was 4.2 mm (3.7–4.8), for the medial one-and-a-half walls it was 2.9 mm (2.1–3.7), and for the two-and-a-half walls it was 7.6 mm (5.8–9.4). The most common complications were temporary postoperative numbness (29% of lateral decompressions, 17% of other bony decompressions, OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.12–2.11) and new postoperative diplopia (9% of lateral decompressions, 39% of other bony decompressions, OR 6.8, 95% CI 1. 5–30.9). Systematic literature searching showed reduction in exophthalmometry for lateral wall surgery of 3.6–4.8 mm, with new diplopia 0–38% and postoperative numbness 12–50%. For other bony decompressions, reduction in exophthalmometry was 2.5–8.0 mm with new diplopia 0–45% and postoperative numbness up to 52%.

Conclusion

Differing approaches to orbital decompression exist. If the correct type of surgery is chosen, then safe, adequate surgical outcomes can be achieved.

Introduction

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a heterogeneous condition characterised by inflammation of the extraocular muscles and other orbital tissues. Surgical management of TED may include orbital decompression, defined as any surgical procedure to reduce intraorbital pressure and its effects by the means of enlargement of the bony orbit and/or removal of orbital fat.1 Indications for surgery include sight-threatening compressive optic neuropathy, raised intra-orbital pressure (hydraulic thyroid eye disease), exposure keratopathy, and improved cosmesis for people with stable, disfiguring exophthalmos. Various techniques for orbital decompression exist; they vary in the incision/approach used and in which part of the orbit is removed. For bony decompression, the medial wall, orbital floor, and lateral wall may be removed. Depending on the severity of exophthalmos, removal of orbital fat may also be considered.1, 2 A recent study from Sweden has shown the positive impact that orbital decompression surgery can have on quality-of-life outcomes.3

In 2011, a new technique was described by Geoffrey Rose for lateral (single) wall, rim sparing orbital decompression.4, 5 Results from a small case series on this technique showed it could achieve a moderate decompression effect (mean 4.8 mm) and had low complication rates.4

It has become our practice in Sheffield to use a modified version of the Rose technique for lateral orbital (single) wall decompressions in patients with moderate proptosis. In patients with severe proptosis, a two-and-a-half wall decompression is usually chosen (where the medial wall, medial half of the floor, and lateral wall are removed); and for patients with sight-threatening orbitopathy, a medial one-and-a-half wall approach (where the medial wall and medial half of the floor is removed) is used after a trial of three daily/alternate day injections of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone. Orbital fat decompression alone is done in cases with mild proptosis.

We describe here our clinical practice, methods, and outcomes for orbital decompressions. We put this into the context of a systematic literature review of outcomes from surgical decompressions. Our hope is that this will help to define acceptable clinical standards and aid clinicians in decision making when considering orbital decompression for patients suffering from TED.

Materials and methods

As part of an evaluation of our orbital decompression service, we carried out a retrospective review of the case notes for all patients who underwent orbital decompression surgery for TED at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield between January 2009 and December 2015 under the care of a single orbital surgeon (SMS). Data were gathered using a standardised proforma. Statistical analysis was carried out using RStudio (Boston, MA, USA) and IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22 Armonk, NY, USA).

Surgical techniques

We describe here our surgical techniques, videos of which are available as uploaded Supplementary Information.

Lateral (single) wall decompression surgery with a modified Rose technique

See Supplementary Movie 1 for a video of this procedure. Under general anaesthetic, 0.5% marcaine with adrenaline is infiltrated around a limited lateral canthotomy site (without detaching the superior or inferior crus of the lateral canthal tendon). Intravenous antibiotics are administered. A Colorado needle (monopolar diathermy) is used to dissect down to the lateral wall. The lateral wall is then completely exposed with the aid of Stevens tenotomy scissors and Desmarres’ retractors. The periosteum is incised along the length of the lateral wall with monopolar diathermy ∼10 mm behind the orbital rim. A periosteal flap is then elevated anteriorly from the outer aspect of the lateral wall, around the rim, and then along the inner aspect of the lateral wall by gentle dissection with a Freer elevator and malleable retractor. The exposed zygomaticotemporal and zygomaticofacial arteries are then cut with monopolar cautery. The deeper periosteum is further elevated inferiorly along the inferior orbital fissure, posteriorly up to the superior orbital fissure, and superiorly to expose the lacrimal gland fossa. This is done visualising the exposed area from the lateral orbital rim with a headlight at all times. The periosteum is also elevated posteriorly from the outer aspect of the lateral wall along with temporalis muscle, to which heavy diathermy is then applied.

Saw, hammer and chisel, and then bone rongeurs (Kerrison bone punches) are used to make a rim sparing lateral wall osteotomy (ab-externo) as developed by Mr Geoffrey Rose. The globe is protected throughout the surgery with the aid of appropriate sized malleable retractors. Modification of Rose technique includes further deeper decompression into the trigone and cortical part of the greater wing of sphenoid with the use of burrs: the round fluted soft touch burr (Stryker) is used to cautiously remove further posterolateral bone, whereas the round diamond burr (Stryker) is used to smooth the edges of the decompression and in areas where the exposure is presumed to be close to the underlying dura. The diamond tip burr can also be used without irrigation for haemostasis along with bone wax. The periosteum encasing the lateral orbital contents is then opened over the osteotomy site and lacrimal gland using the Colorado needle and then stripped off the underlying orbital fat and lacrimal gland. This allows prolapse of lateral orbital fat, lateral rectus, and lacrimal gland into the new opening that is encouraged by applying pressure on the eye through the lids. The orbital fat pads, bands, and septae are opened by blut dissection using Stevens scissors above and below lateral rectus, taking due care of the lacrimal artery and other vessels. Decompression effect can be further enhanced if needed with debulking of the inferolateral fat pad. The residual anterior leaf of the periosteum is redraped over the lateral orbital rim and anchored to the posterior leaf of the periosteum. A monovac drain is applied before closure of the limited lateral canthotomy opening. We infiltrate the lower lid with 0.5% marcaine with adrenaline for post op analgesia; this also has the benefit of inducing downward pressure on the globe, encouraging it to sit deeper in the orbit and prolapsing the desired orbital contents into the newly created lateral wall decompression site. A firm pressure dressing is applied for 12–24 h and the monovac drain removed once it is confirmed that there is no active drainage. Intravenous methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg) is administered on first postoperative day before discharge from hospital to reduce inflammation

An ab-interno approach where the deep lateral wall is burred internally, although not our preferred method in Sheffield, may have the advantage of reducing the surgical time. It was used in one patient in the current series because of her high general anaesthetic risk and the desire for a reduced operative time.

Medial one-and-a-half wall orbital decompression surgery

See Supplementary Movie 2 for a video of this procedure. Surgery is done under general anaesthetic with a throat pack and intravenous antibiotic is administered at the onset of surgery. A 2.0 silk suture is passed through the medial aspect of the upper and lower eyelids to open the eyelids and expose the caruncular area widely. Marcaine 0.5% with adrenaline is infiltrated into the medial part of the eyelids, vertically along the medial wall of the orbit and between the plica and caruncular area to create a plane of dissection. The Colorado needle is used to make a retrocaruncular incision above the plica semilunaris and extending into the superior and inferior fornix region. Closed Stevens scissors are used at an angle of 30–45° to reach the posterior lacrimal crest and then gently opened to achieve blunt dissection without opening the medial fat pad. Desmarre retractor and small malleable retractors are used to reach the medial orbital wall. The periosteum is opened horizontally behind the posterior lacrimal crest with the Colorado needle and reflected gently off the medial wall with a Freer elevator and increasing sizes of malleable retractors, taking care not to breach the periobita at this stage. The upper margin of the periosteal reflection is up to the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, the deeper margin is to the optic canal, and the lower margin is extended onto the floor, lateral to the infraorbital nerve. Visualisation is from the retrocaruncular opening with the aid of a headlight. A mid and posterior ethmoidectomy is performed with Watson Wilkins forceps and Tilly forceps, aided by suction. The medial half of the orbital floor, medial to the infraorbital nerve, is removed extending as posteriorly as possible taking care to diathermy the vessel entering the infraorbital nerve. The mid and posterior part of the inferomedial strut is removed until the Triradiate point is exposed (the Mercedes sign as taught by Mr Rose—personal communication with SMS). The anterior part of the strut along with its neighbouring anterior ethmoid is not removed as we believe this residual bony area helps support the globe and its removal does not enhance the effect of the decompression.

The sphenoid cavity is then entered via the posterior ethmoid and any remaining posterior ethmoidal bone anterior to the optic canal is removed to complete the medial one-and-a-half wall decompression at the apex.

The periosteum is then opened and stripped in a posterior to anterior direction to prolapse the medial rectus and the superomedial and inferomedial orbital fat pads into the decompressed area. The orbital fat pads, bands, and septae are then opened by blunt dissection with Stevens scissors and pressure is applied on the globe to further facilitate prolapse of the orbital contents into the newly created decompression site. This allows pressure to be released off the optic nerve by reducing crowding at the orbital apex. The newly created space may also allow for inferomedial movement of the optic nerve itself, thus easing the pressure on it at the orbital apex. The retrocaruncular conjunctival incision site is then closed with interrupted 7.0/8.0 vicryl sutures and a pressure dressing applied and left in place for 12–24 h.

Other decompressions: two-and-a-half wall orbital decompression, balanced two wall surgery, and fat decompression

A two-and-a-half wall decompression includes performing the lateral wall decompression surgery along with a medial one-and-a-half wall decompression surgery. When a lateral wall decompression is done with medial wall decompression alone (without removing the medial half of the orbital floor) it is termed as a balanced decompression.

In fat decompression, the inferolateral fat pad is debulked (and superolateral fat pad if required). This is done via a transconjunctival incision made on the inner aspect of the lateral canthus over the lateral orbital rim and extended inferiorly and superiorly as required.

Systematic literature review

In order to put in context the results of this case series we also carried out a literature review. We carried out an initial search of MEDLINE as follows: ‘Decompression, Surgical’ [Major search term] AND ‘Graves Ophthalmopathy’ [MESH search term]. We restricted the search to a 10-year period (search performed in July 2017). Articles not written in English were excluded. Experts in the field were consulted. Reference lists of identified primary reports and review articles were searched. Abstracts were carefully reviewed and relevant papers then considered in detail. We included studies that looked at outcomes for surgical decompression in TED, including bony and/or fat decompressions and open and/or endoscopic approach. Studies were excluded if they did not include outcome data measured by Hertel exophthalmometry.

Results

During the audited period, a total of 57 patients underwent orbital decompression for presumed TED. Case notes were available for all patients. Two patients who had co-pathology identified at biopsy during surgery (MALTOMA and Ig4 disease) were excluded from the remaining analysis. The baseline characteristics for the included 55 patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 55 patients included in the study.

|

Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (24%) |

| Female, n (%) | 42 (76%) |

| Age at diagnosis of TED, mean (SD) | 46.6 (14.2) |

| Age at the time of first eye decompression, mean (SD) | 51.0 (13.9) |

| Initial thyroid status | |

| Hyperthyroid, n (%) | 42 (76%) |

| Euthyroid, n (%) | 4 (7%) |

| Hypothyroid, n (%) | 3 (5%) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 6 (11%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current, n (%) | 22 (40%) |

| Ex, n (%) | 10 (18%) |

| Never, n (%) | 23 (42%) |

| Baseline visual acuity in better-seeing eye | |

| 6/6 or better, n (%) | 43 (78%) |

| 6/9 or better, n (%) | 54 (98%) |

| 6/12 or better, n (%) | 55 (100%) |

| Baseline visual acuity in poorer-seeing eye | |

| 6/6 or better, n (%) | 24 (44%) |

| 6/9 or better, n (%) | 44 (80%) |

| 6/12 or better, n (%) | 45 (82%) |

| CAS score pre-op, mean (SD) | 1.4 (2.0) |

| Sight threatening | 3.9 (2.5) |

| Non-sight threatening | 0.9 (1.4) |

Of the 55 patients, 28 (51%) had bilateral surgery, 10(18%) had sequential orbit surgery, and 17 (31%) had unilateral surgery. This gave a total of 93 operated orbits. Table 2 shows the type of surgery and indication for these 93 orbits.

Table 2. Type of surgery, and indication for the 93 operated orbits.

| Type of surgery | Indication |

|---|---|

| Lateral (single) wall (n=61) | Hydraulic TED: 21 (34%) |

| Burnt-out TED with stable proptosis: 40 (66%) | |

| Medial one-and-a-half wall (n=17) | Sight-threatening orbitopathy: 17 (100%) |

| Two-and-a-half wall (n=11) | Sight-threatening orbitopathy: 2 (18%) |

| Hydraulic TED: 2 (18%) | |

| Burnt-out TED with stable proptosis: 7 (64%) | |

| Balanced two wall (n=2) | Burnt-out TED with stable proptosis: 2 (100%) |

| Orbital fat only (n=2) | Burnt-out TED with stable proptosis: 2 (100%) |

The reduction in exophthalmometry readings and percentage decrease in this reduction for the three main types of bony surgery are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of mean pre- and postoperative Hertel exophthalmometry readings using two-tailed paired t-tests and mean percentage decreases (absolute reduction in proptosis/preoperative exophthalmometry) according to type of surgery.

| Type of surgery | N | Mean pre-op | Mean post-op | Difference between means | 95% CI | P-value | Mean % decrease | SD % decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral (single) wall | 61 | 23.5 | 19.3 | 4.2 | 3.7–4.8 | <0.0001 | 17.9 | 8.1 |

| Two-and-a-half wall | 11 | 27.8 | 20.2 | 7.6 | 5.8–9.4 | <0.0001 | 26.7 | 7.0 |

| Medial one-and-a-half wall | 17 | 23.0 | 20.2 | 2.9 | 2.1–3.7 | <0.0001 | 12.3 | 5.6 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

A total of 78 (84%) eyes had a postoperative exophthalmometry reading of ⩽21 mm, 82 (88%) had a reading of ⩽22 mm, and 91 (98%) had ⩽24 mm.

Final visual acuities were 6/6 or better for 59 (63%) eyes and 6/9 or better for 84 (90%) eyes. A total of 19 eyes of 10 patients had decompression surgery for dysthyroid optic neuropathy (DON). Of these 10 patients, 7 (70%) were current or recent ex-smokers. For the 10 patients with DON, diagnosis of DON was based on decreased vision (6/12 or less in worse eye, n=7), RAPD (n=9), decreased colour vision (n=8), and apical crowding on CT (n=10). Postoperatively, 8/19 (42%) eyes achieved vision of 6/6 or better and 14/19 (74%) eyes had vision of 6/9 or better. One patient who underwent bilateral surgery for DON had further deterioration in vision postoperatively in one eye (to HM); this patient had been reluctant for initial surgery and declined further surgery, steroid treatment, or radiotherapy; she recovered and maintained good vision in the fellow eye (6/9) following surgery.

One patient who had bilateral medial one-and-a-half wall decompressions for sight-threatening TED developed decreased vision, a right RAPD, and swollen disc 6 weeks later. He then went on to have intravenous methylprednisilone, immunosuppression with azathioprine, further bilateral lateral wall decompression, orbital radiotherapy, and thyroidectomy for the disease to burn out. No other patients in this series required further decompression surgery.

Preoperative diplopia was reported in 21 (38%) patients, and this was improved by decompression surgery in 6 patients, such that 15 (27%) patients still had diplopia postoperatively. There were an additional 10 (18%) patients with new diplopia following orbital decompression. Postoperative numbness in the zygomatico-temporal/zygomatico-facial territory was reported by 13 (24%) patients. This symptom was mild and temporary (<3 months) in all but one person who had ongoing symptomatic numbness. Table 4 shows the number of patients experiencing these common complications.

Table 4. Rates of the two most common complications and further procedures.

| All patients having bony decompression (n=53) | Patients undergoing lateral wall decompression only (n=35) | Patients undergoing other bony decompression or a combination (n=18) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative numbness | 13 (25%) | 10 (29%) | 3 (17%) | 0.50 | 0.12–2.11 |

| New postoperative diplopia | 10 (19%) | 3 (9%) | 7 (39%) | 6.79 | 1.49–30.9 |

| Squint surgery | 18 (34%) | 6 (17%) | 12 (67%) | 9.67 | 2.59–36.1 |

| Squint surgery for new postoperative diplopia | 5 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (28%) | ||

| Lid surgery | 13 (25%) | 6 (17%) | 7 (39%) | 3.08 | 0.85–11.20 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Patients having only fat decompression are excluded from this Table (n=2) and a comparison is made between patients who had lateral wall decompression only (either bilateral or unilateral) and patients undergoing any other bony orbital decompression.

There was one case of an acute sub-dural haemorrhage in the immediate postoperative period needing urgent neurosurgical intervention. This was following bilateral lateral wall decompressions using an ab-interno technique (the only case in the current series that used the ab-interno technique). The patient was a 65-year-old female who had been a heavy smoker with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, angina, and a previous pulmonary embolus. She was keen for decompression surgery despite clear counselling of the risks involved. The ab-interno approach was chosen in an attempt to reduce surgical time in light of her anaesthetic risk. Surgery was uneventful and on the left side the dura was exposed (though not breached). Following a turbulent extubation she had altered sensorium and was found to have a tense socket on the left side. Urgent imaging showed a left-sided orbital haemorrhage extending from a sub-dural haemorrhage to be the cause. We postulate that this occurred as a result of haemorrhage from a bridging vessel through an area of exposed dura at the decompression site. Following neurosurgical intervention she eventually made a good recovery with final visual acuities of 6/7.5 in each eye with 3 and 0.5 mm reduction in proptosis on right and left side, respectively.

One patient who had bilateral lateral wall decompressions developed an inferior corneal perforation secondary to corneal exposure 10 months postoperatively. This was secondary to a combination of a lagopthalmos (due to inferior lid retraction) and an absent Bells’ phenomenon (due to a tight, scarred inferior rectus) and occurred while the patient was waiting for inferior rectus recession surgery. The corneal perforation was managed successfully with corneal gluing and botox (to induce complete ptosis), and later a temporary tarsorrhaphy. The underlying lower eyelid retraction was later managed with a lower eyelid heightening and lateral tarsal strip procedure. Following this there was still some mild residual lagophthalmos that was managed with a gold weight.

One patient, who also had rheumatoid arthritis, developed a postoperative scleritis 2 weeks after bilateral lateral wall decompressions that was managed with high-dose oral steroids. Another two patients having lateral wall decompressions developed postoperative orbital inflammation and were both treated successfully with a tapering course of oral steroids.

Of the 55 patients, 18 (33%) went on to have squint surgery. Of the 10 patients with new diplopia following their decompression surgery, 5 (50%) required squint surgery. No patients with new diplopia following lateral decompression surgery required squint surgery (Table 4). Lid surgery was carried out in 13 (25%) patients following their decompression (see Table 4).

There were postoperative exophthalmometry data for 23 eyes following squint surgery. For these 23 eyes, the mean pre-squint surgery (post decompression) exophthalmometry reading was 20.3 mm (SD 2.08) and post-squint surgery it was 19.3 mm (SD 2.49). The difference between these means was 0.98 mm and this was significant with a 2 -tailed paired t-test (P=0.038, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06–1.90).

Results of literature review

A total of 113 abstracts were identified by our search, those that met the inclusion criteria and are included in Table 5.

Table 5. Results from literature search.

| Study | Place | Study type | n | Type of decompression | Mean reduction in Hertel exophthalmometry (mm) | New diplopia | New numbness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat only decompressions (3.6–4.2 mm) | |||||||

| Li et al7 | Hong-Kong | Case series | 11 Patients (21 orbits) | Orbital fat | 4.2 mm | 0% | 0% |

| Liao et al8 | Taiwan | Case series | 22 Patients (44 orbits) | Orbital fat | 4.1 mm | ND | ND |

| Wu et al9 | Taiwan | Case series | 120 Patients (222 orbits) | Orbital fat | 3.6 mm | 2.8% | ND |

| Endoscopic approaches (2.1–8 mm) | |||||||

| Lv et al10 | China | Case series | 43 Patients (72 orbits) | Endoscopic medial one-and-a-half wall | 6.2 mm | 12% | ND |

| Miśkiewicz et al11 | Poland | Prospective case series | 14 Eyes | Endoscoptic medial wall | 1.0 mm | 14% | ND |

| Kingdom et al12 | USA | Case series | 77 Patients (114 orbits) | Endoscopic three wall | 3.2 mm | 0% | ND |

| Thapa et al13 | India | Comparative case series | 15 Patients (28 orbits) | Endoscopic medial or medial one-and-a-half wall | 3.4 mm | 0% | 0% |

| Wu et al14 | China | Case series | 108 Patients (206 orbits) | Endoscopic medial wall | 8.0 mm | 23% | 0% |

| Gulati et al15 | Norway | Case series | 37 Patients (66 orbits) | Endoscopic medial wall | 4.0 mm | 19% | 0% |

| She et al16 | Taiwan | Case series | 25 Patients (42 orbits) | Endoscopic medial one-and-a-half wall | 2.1 mm | 4% | ND |

| Chu et al17 | USA | Case series | 5 Patients (6 orbits) | Endoscopic decompression of orbital apex | 3.1 mm | 0% | ND |

| Nonendoscopic lateral (single) wall decompressions (3.6–4.8 mm) | |||||||

| Miller18 | UK | Case series | 41 Orbits | Lateral wall | 4.0 mm | 6% | 12% |

| Ueland et al19 | Norway | Case series | 84 Patients (144 orbits) | Lateral wall | 3.6 mm | 5% | 50% |

| Nguyen et al20 | USA | Case series | 69 Patients (108 orbits) | Lateral wall | 3.7 mm | ND | ND |

| Mehta and Durrani4 | UK | Case series | 17 Patients (21 orbits) | Lateral wall | 4.8 mm | 0% | 18% |

| Sellari-Franceschin et al21 | Italy | Case series | 39 Patients (72 orbits) | Lateral wall | 4.5 mm | 0% | 24% |

| Chang and Piva22 | Costa Rica | Case series | 33 Patients (65 orbits) | Lateral wall | 4.5 mm | 3% | ND |

| Nonendoscopic bony decompressions/articles presenting a mixture of types of decompression (1.9–7.2 mm) | |||||||

| Yao et al23 | USA | Case series | 73 Patients (115 orbits) | Balanced two wall | 5.0 mm | 17% | ND |

| Choi et al24 | Korea | Case series | 24 Patients (48 orbits) | Balanced two wall | 4.0 mm | 2% | 8% |

| Wu et al 25 | USA | Case series | 53 Patients (80 orbits) | Balanced two wall | 5.6 mm | ND | ND |

| Kim et al26 | Korea | Case series | 23 Patients (43 orbits) | Balanced two wall or three wall | 4.1 mm | ND | ND |

| Korkmaz and Konuk27 | Turkey | Comparative case series | 42 Patients (68 orbits) | Balanced two wall (41 orbits) or three wall (27 orbits) | 5.1 mm (2 wall) 7.2 mm (3 wall) | 20% (2 wall) 29% (3 wall) | ND |

| Onaran et al28 | Turkey | Case series | 36 Patients (72 eyes) | Balanced two wall | 6.2 mm | ND | ND |

| Sagiv et al29 | Australia and Israel | Comparative case series | 112 Patients (186 orbits) | Two wall (89 orbits) or three wall (97 orbits) | 4.6 mm (2 wall) 5.4 mm (3 wall) | 13% | ND |

| Kim et al30 | South Korea | Comparative case series | 21 Patients (33 orbits) | Two wall (25 orbits) or three wall (8 orbits) | 4.5 mm (2 wall) 5.1 mm (3 wall) | ND | ND |

| Ponto et al31 | Germany | Case series | 40 Patients (62 orbits) | Two wall (27 orbits) or three wall (35 orbits) | 3.0 mm | 18% | 52% |

| Bingham et al32 | USA | Case series | 4 Patients (8 orbits) | Three wall | 4.0 mm | 0% | ND |

| Lee et al33 | South Korea | Comparative case series | 55 Patients (90 orbits) | Fat only (29 orbits), medial one wall (15 orbits), two wall (36 orbits), and two wall with minimal fat removal (19 orbits) | 3.8 mm (orbital fat) 4.0 mm (medial one wall) 5.1 mm (2 wall) 3.4 mm (2 wall, minimal fat) | 36% | ND |

| Roncevic et al34 | Serbia | Case series | 65 Patients | Three wall | 7.2 mm | 0% | ‘Majority’ |

| Fayers et al5 | UK | Case series | 98 Patients (163 orbits) | Lateral wall (76 orbits) or lateral and medial and/or floor (87 orbits) | 3.7 mm (lateral) 5.7 mm (all types) | ND | ND |

| Clauser et al35 | Italy | Case series | 131 Patients (196 orbits) | Fat only decompression (137 orbits) or three wall bony decompression (59 orbits) | 3.9 mm | 4% | ND |

| Hill et al36 | USA | Case series | 16 Patients (16 orbits) | Medial wall | 2.3 mm | 22% | ND |

| Rocchi et al37 | Italy | Comparative case series | 247 Patients | Two wall (197 patients) or lateral (single) decompression (50 patients) | 5.7 mm (2 wall) 4 mm (lateral) | 18% (2 wall) 0% (lateral) | ND |

| Norris et al38 | UK/USA/Australia | Prospective multicentre case series | 33 Patients (52 orbits) 6 orbits | Fat only (6 orbits), lateral wall (13 orbits), balanced two wall (26 orbits), three wall (7 orbits) | 2.8 mm (fat only) 4.8 mm (lateral) 4.4 mm (2 wall) 5.6 mm (3 wall) | ND | ND |

| Alsuhaibani et al39 | Saudi Arabia | Case series | 20 Patients (38 orbits) | Balanced two wall | 2.5 mm | 45% | ND |

| Perez-Lopez et al40 | Spain | Case–control study | 14 Patients (26 orbits) | Medial one wall (4 orbits), balanced two wall (10 orbits), three wall (12 orbits) | 2.5 mm (medial) 5 mm (2 wall) 7 mm (3 wall) | ND | ND |

| Choe et al41 | USA | Comparative case series | 17 Patients (28 orbits) | Medial wall (18 orbits) Lateral wall (10 orbits) | 3.1 mm (medial wall) 6.3 mm (lateral wall) | ND | ND |

| Chu et al42 | USA | Comparative case series | 69 Patients (112 orbits) | External balanced two wall decompression (32 orbits), endoscopic medial one-and-a-half wall (32 orbits), combined endoscopic/external three wall decompression (48 orbits) | 5.9 mm(external 2 wall) 1.9 mm (endoscopic medial 1.5 wall) 7.4 mm (endoscopic/external 3 wall) | 0% (combined/external) 9% (endoscopic) | ND |

| Maalouf et al43 | France | Cross-sectional | 19 Patients (36 orbits) | Medial one-and-a-half wall | 2.8 mm | ND | 20% |

| O’Malley et al44 | USA | Case series | 28 Patients (52 orbits) | Medial one-and-a-half wall | 3.3 mm | 4% | ND |

| Mourits et al2 | 11 European centres | Multi-centre case series | 139 Patients (248 orbits) | Variety of two wall and three wall approaches | 5 mm | ND | Up to 36% |

| Dubin et al45 | USA | Case series | 24 Patients (45 orbits) | Balanced two wall | 6.2 mm | 29.2% | ND |

| Jernfors et al46 | Finland | Case series (long-term outcomes) | 78 Patients | Medial one-and-a-half wall (mostly transantral, some endoscopic) | 4.4–4.7 mm | 8.5% | 28% |

Abbreviation: ND, not documented.

Discussion

In this evaluation of our decompression service of patients under the care of one orbital surgeon in Sheffield, UK, we have shown our methods, outcomes, and complications for 91 orbital decompressions and put these in the context of a systematic literature review. As a general rule of thumb, lateral (single) wall decompression was preferred for hydraulic TED or disfiguring exophthalmos with moderate proptosis (3–7 mm). In cases with severe proptosis (>7 mm), two-and-a-half wall decompression was preferred (Table 2). We chose medial one-and-a-half wall decompression for dysthroid optic neuropathy (by removing the medial orbital wall and posterior floor, the optic nerve is immediately given space to move inferomedially).

With lateral (single) wall decompressions we saw a reduction in exophthalmometry readings of 4.3 mm and with two-and-a-half wall decompressions a mean reduction in exophthalmometry of 7.6 mm. The mean reduction in exophthalmometry was 2.7 mm with the medial one-and-a-half wall approach. Interestingly, for all types of decompression the mean post-operative exophthalmometry fell close to 20 mm (Table 3). It is important to note that these procedures are not inflexible and that they are tailored to the individual need: intraoperatively, bony removal can be stopped when sufficient decompression effect is noted (when the posterior part of the globe is positioned behind the lateral orbital rim or symmetry with the contralateral side is achieved). Caution therefore needs to be exercised when interpreting the values of reduction in exophthalmometry readings in ours and other series.

Common complications included postoperative numbness and postoperative diplopia. Lateral (single) wall decompressions had a higher rate of postoperative numbness when compared with other bony decompression types, although this was not statistically significant (Table 4). It is important that postoperative numbness is mentioned as a potential complication for patients undergoing other decompression types and not just lateral orbital decompression. New-onset diplopia was less common following lateral decompressions compared with other bony decompressions (significantly so this time—Table 4). Furthermore, for the small number (9%) of patients experiencing new-onset diplopia in the primary position following lateral wall decompression surgery, none went on to require squint surgery (Table 4). This generally mild and transient diplopia following lateral wall decompression was likely due to adjustment to the new globe position following surgery. In contrast, 5 of the 7 patients (71%) with new-onset diplopia following other bony decompression surgery went on to require squint surgery. Patients undergoing lateral wall decompressions need to be counselled about the risk of new diplopia, although in contrast to other decompressions, this is unlikely to require further intervention in terms of squint surgery. Serious complications were rare in our case series. However, one patient with severe medical comorbidities had a life-threatening complication (subdural haemorrhage) requiring urgent neurosurgical intervention. An ab-interno approach was used in this patient in an attempt to reduce the surgical time for a patient with considerable anaesthetic risk. However, the ab-interno approach is not our preferred method as, in our experience, it gives poorer access and visualisation of the decompression site when compared with the ab-externo modified Rose technique. In hindsight, this surgical decision could have been a contributory factor to the complications in this case. This case highlights that this is not a risk-free surgery and patient selection with a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits for patients electing non-sight-threatening decompression surgery is paramount.

It is important to remember that patients are at risk of activation of other inflammatory and autoimmune conditions following the insult of surgery (a case of scleritis and two other reactivations of orbital inflammation in this series). Intravenous methylprednisolone should be considered perioperatively to guard against this as well as close monitoring in the early postoperative period. Furthermore, surgery does not prevent the new development of dysthyroid orbitopathy or other sight-threatening complications such as exposure keratophathy and hence patients need to be counselled about this and followed up appropriately.

Dysthyroid optic neuropathy can be a rapidly progressive and blinding condition, but with adequate immunosuppression and surgery the visual outcomes can be excellent. A pertinent lesson from our series is the importance of patient trust, understanding, and cooperation. In the one patient where there was poor compliance with treatment, the final visual outcome was poor. It is also important to closely monitor and treat any continued clinically active thyroid eye disease postoperatively with immunosuppression/orbital radiotherapy as medial one-and-a-half wall decompression surgery will simply deal with the acute optic neuropathy episode.

We found that squint surgery following orbital decompression does not undo the decompression effect as we suspected it might (we had presumed that the recession surgery on rectus muscles may cause the globe to lux forward and thus undo the reduction in proptosis caused by decompression surgery). Instead, there was a significant reduction in exophthalmometry readings post squint surgery that is likely because of a tendency for the decompression effect to increase over time in spite of squint surgery.

This study is not without its limitations. It presents a retrospective case review of orbital decompressions from a service evaluation of patients under the care of a single surgeon. As such, the transferability of the data needs to be taken with care. It is for this reason that we have put our results within the context of the wider literature on the subject through systematic literature searching.

Our literature search showed a vast array of differing surgical approaches from around the world (Table 5). We limited our literature search to the past 10 years as techniques have evolved considerably in this time period such that older studies become increasingly less meaningful. Lateral wall decompression results were similar to ours in the current series with decompression effects of 3.6–4.8 mm, risk of new diplopia 0–38%, and risk of postoperative numbness up to 50%. We suspect that the widely differing reports of postoperative numbness are because of the variable reporting and questioning about this generally mild postoperative symptom. The other bony decompressions (endoscopic or external) had decompression effects between 1.9 and 8 mm with a general rule that with more walls removed there was a greater decompression effect. The risk of new diplopia ranged from 0 to 45% and new numbness from 0 to 50%. A Cochrane review of orbital decompressions found only one randomised control study comparing two types of surgery.6 This study from Mexico showed similar outcomes, but differing complication rates for the Walsh–Ogura transantral technique and the Kennedy endoscopic endonasal approach. Neither of these techniques is any longer employed in wide clinical practice. As such, the evidence base behind our decision making for decompressions in TED lies very much within expert opinion and the case series' detailed in Table 5. Assimilation of these case series here will hopefully guide decision making and direct future prospective studies.

In summary, surgical orbital decompressions are an established procedure for the management of certain patients with TED. Lateral decompressions are safe and effective for hydraulic TED and stable proptosis and have low complication rates. Where there is severe proptosis, two-and-a-half wall decompression may be more suitable, but the risk of new postoperative diplopia is higher. For dysthyroid optic neuropathy not responding to immunosuppression, medial one-and-a-half wall decompression is usually the surgery of choice and has good results in restoring visual function where there is good patient compliance and understanding.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Eye website (http://www.nature.com/eye)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baldechi LOrbital decompression. In: Wiersinga WM, Kahaly GJ(eds). Graves' Orbitopathy: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2007, Karger, Basel, pp 163–175.

- Mourits MP, Bijl H, Altea MA, Baldeschi L, Boboridis K, Currò N et al. Outcome of orbital decompression for disfiguring proptosis in patients with Graves' orbitopathy using various surgical procedures. Br J Ophthalmol 2009; 93(11): 1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobaeus L, Sahlin S. Evaluation of quality of life in patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, before and after orbital decompression. Orbit 2016; 35(3): 121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P, Durrani OM. Outcome of deep lateral wall rim-sparing orbital decompression in thyroid-associated orbitopathy: a new technique and results of a case series. Orbit 2011; 30(6): 265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayers T, Barker LE, Verity DH, Rose GE. Oscillopsia after lateral wall orbital decompression. Ophthalmology 2013; 120(9): 1920–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boboridis KG, Bunce C. Surgical orbital decompression for thyroid eye disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (12): CD007630. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li EY, Kwok TY, Cheng AC, Wong AC, Yuen HK. Fat-removal orbital decompression for disfiguring proptosis associated with Graves' ophthalmopathy: safety, efficacy and predictability of outcomes. Int Ophthalmol 2015; 35(3): 325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SL, Huang SW. Correlation of retrobulbar volume change with resected orbital fat volume and proptosis reduction after fatty decompression for Graves ophthalmopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2011; 151(3): 465–9 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Chang TC, Liao SL. Results and predictability of fat-removal orbital decompression for disfiguring graves exophthalmos in an Asian patient population. Am J Ophthalmol 2008; 145(4): 755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z, Selva D, Yan W, Daniel P, Tu Y, Wu W. Endoscopical orbital fat decompression with medial orbital wall decompression for dysthyroid optic neuropathy. Curr Eye Res 2016; 41(2): 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miśkiewicz P, Rutkowska B, Jabłońska A, Krzeski A, Trautsolt-Jeziorska K, Kęcik D et al. Complete recovery of visual acuity as the main goal of treatment in patients with dysthyroid optic neuropathy. Endokrynol Pol 2016; 67(2): 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom TT, Davies BW, Durairaj VD. Orbital decompression for the management of thyroid eye disease: an analysis of outcomes and complications. Laryngoscope 2015; 125(9): 2034–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa S, Gupta AK, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dutta P, Virk RS. Proptosis reduction by clinical vs radiological modalities and medial vs inferomedial approaches: comparison following endoscopic transnasal orbital decompression in patients with dysthyroid orbitopathy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 141(4): 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Selva D, Bian Y, Wang X, Sun MT, Kong Q et al. Endoscopic medial orbital fat decompression for proptosis in type 1 graves orbitopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2015; 159(2): 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati S, Ueland HO, Haugen OH, Danielsen A, Rodahl E. Long-term follow-up of patients with thyroid eye disease treated with endoscopic orbital decompression. Acta Ophthalmol 2015; 93(2): 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She YY, Chi CC, Chu ST. Transnasal endoscopic orbital decompression: 15-year clinical experience in Southern Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2014; 113(9): 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu EA, Miller NR, Lane AP. Selective endoscopic decompression of the orbital apex for dysthyroid optic neuropathy. Laryngoscope 2009; 119(6): 1236–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Cauchi P. Surgical Outcomes in Lateral Orbital Wall Decompression (Abstract). British Oculoplastic Surgery Society: Glasgow, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ueland HO, Haugen OH, Rodahl E. Temporal hollowing and other adverse effects after lateral orbital wall decompression. Acta Ophthalmol 2016; 94(8): 793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J, Fay A, Yadav P, MacIntosh PW, Metson R. Stereotactic microdebrider in deep lateral orbital decompression for patients with thyroid eye disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2014; 30(3): 262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellari-Franceschini S, Lenzi R, Santoro A, Muscatello L, Rocchi R, Altea MA et al. Lateral wall orbital decompression in Graves' orbitopathy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 39(1): 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EL, Piva AP. Temporal fossa orbital decompression for treatment of disfiguring thyroid-related orbitopathy. Ophthalmology 2008; 115(9): 1613–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao WC, Sedaghat AR, Yadav P, Fay A, Metson R. Orbital decompression in the endoscopic age: the modified inferomedial orbital strut. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016; 154(5): 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SU, Kim KW, Lee JK. Surgical outcomes of balanced deep lateral and medial orbital wall decompression in Korean population: clinical and computed tomography-based analysis. Korean J Ophthalmol 2016; 30(2): 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CY, Stacey AW, Kahana A. Simultaneous versus staged balanced decompression for thyroid-related compressive optic neuropathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2016; 32(6): 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Chun YS, Cho BY, Lee JK. Biometric and refractive changes after orbital decompression in Korean patients with thyroid-associated orbitopathy. Eye (Lond) 2016; 30(3): 400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz S, Konuk O. Surgical treatment of dysthyroid optic neuropathy: long-term visual outcomes with comparison of 2-wall versus 3-wall orbital decompression. Curr Eye Res 2016; 41(2): 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaran Z, Konuk O, Oktar SO, Yucel C, Unal M. Intraocular pressure lowering effect of orbital decompression is related to increased venous outflow in Graves orbitopathy. Curr Eye Res 2014; 39(7): 666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv O, Satchi K, Kinori M, Fabian ID, Rosen N, Ben Simon GJ et al. Comparison of lateral orbital decompression with and without rim repositioning in thyroid eye disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016; 254(4): 791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SA, Jung SK, Paik JS, Yang SW. Effect of orbital decompression on corneal topography in patients with thyroid ophthalmopathy. PLoS One 2015; 10(9): e0133612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponto KA, Zwiener I, Al-Nawas B, Kahaly GJ, Otto AF, Karbach J et al. Piezosurgery for orbital decompression surgery in thyroid associated orbitopathy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014; 42(8): 1813–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham CM, Harris MA, Vidor IA, Rosen CL, Linberg JV, Marentette LJ et al. Transcranial orbital decompression for progressive compressive optic neuropathy after 3-wall decompression in severe graves' orbitopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2014; 30(3): 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Jang SY, Lee SY, Yoon JS. Graded decompression of orbital fat and wall in patients with Graves' orbitopathy. Korean J Ophthalmol 2014; 28(1): 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncevic R, Savkovic Z, Roncevic D. Results of diplopia and strabismus in patients with severe thyroid ophthalmopathy after orbital decompression. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014; 62(3): 268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauser LC, Galie M, Tieghi R, Carinci F. Endocrine orbitopathy: 11 years retrospective study and review of 102 patients and 196 orbits. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012; 40(2): 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RH, Czyz CN, Bersani TA. Transcaruncular medial wall orbital decompression: an effective approach for patients with unilateral graves ophthalmopathy. ScientificWorldJournal 2012; 2012: 312361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi R, Lenzi R, Marinò M, Latrofa F, Nardi M, Piaggi P et al. Rehabilitative orbital decompression for Graves' orbitopathy: risk factors influencing the new onset of diplopia in primary gaze, outcome, and patients' satisfaction. Thyroid 2012; 22(11): 1170–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris JH, Ross JJ, Kazim M, Selva D, Malhotra R. The effect of orbital decompression surgery on refraction and intraocular pressure in patients with thyroid orbitopathy. Eye (Lond) 2012; 26(4): 535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsuhaibani AH, Carter KD, Policeni B, Nerad JA. Orbital volume and eye position changes after balanced orbital decompression. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 27(3): 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López M, Sales-Sanz M, Rebolleda G, Casas-Llera P, González-Gordaliza C, Jarrín E et al. Retrobulbar ocular blood flow changes after orbital decompression in Graves' ophthalmopathy measured by color Doppler imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52(8): 5612–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe CH, Cho RI, Elner VM. Comparison of lateral and medial orbital decompression for the treatment of compressive optic neuropathy in thyroid eye disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 27(1): 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu EA, Miller NR, Grant MP, Merbs S, Tufano RP, Lane AP. Surgical treatment of dysthyroid orbitopathy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 141(1): 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf T, Vedrine PO, Coffinet L, George JL. Mid-term rhinosinusal consequences of bony orbital decompression in Graves’ disease: a retrospective study. Orbit 2008; 27(3): 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley MR, Meyer DR. Transconjunctival fat removal combined with conservative medial wall/floor orbital decompression for Graves orbitopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 25(3): 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin MR, Tabaee A, Scruggs JT, Kazim M, Close LG. Image-guided endoscopic orbital decompression for Graves' orbitopathy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2008; 117(3): 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernfors M, Valimaki MJ, Setala K, Malmberg H, Laitinen K, Pitkaranta A. Efficacy and safety of orbital decompression in treatment of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: long-term follow-up of 78 patients. Clin Endocrinol 2007; 67(1): 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.