Abstract

Background/Aim:

A pleural effusion is an abnormal collection of fluid in the pleural space and may cause related morbidity or mortality in cirrhotic patients. Currently, there are insufficient data to support the long-term prognosis for cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion. In this study, we investigated the short- and long-term effects of pleural effusion on mortality in cirrhotic patients and evaluated the benefit of liver transplantation in these patients.

Patients and Methods:

The National Health Insurance Database, derived from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program, was used to identify 3,487 cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010. The proportional hazards Cox regression model was used to control for possible confounding factors.

Results:

The 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 3-year mortalities were 20.1%, 40.2%, 59.1%, and 75.9%, respectively, in the cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion. After Cox proportional hazard regression analysis adjusted by patient gender, age, complications of cirrhosis and comorbid disorders, old age, esophageal variceal bleeding, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic encephalopathy, pneumonia, renal function impairment, and without liver transplantation conferred higher risks for 3-year mortality in the cirrhotic patients with pleura effusion. Liver transplantation is the most important factor to determine the 3-year mortalities (HR: 0.17, 95% CI 0.11- 0.26, P < 0.001). The 30-day, 30 to 90-day, 90-day to 1-year, and 1 to 3-year mortalities were 5.7%, 13.4%, 20.4%, and 21.7% respectively, in the liver transplantation group, and 20.5%, 41.0%, 61.2%, and 77.5%, respectively, in the non-liver transplantation group.

Conclusion:

In cirrhotic patients, the presence of pleural effusion predicts poor long-term outcomes. Liver transplantation could dramatically improve the survival and should be suggested as soon as possible.

Keywords: End-stage liver disease, hepatic hydrothorax, hepatic insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Pleural effusions are abnormal body fluids in the pleural space and may cause related morbidity or mortality in cirrhotic patients. It is well known that the presence of ascites in cirrhotic patients confers a poor prognosis.[1,2,3,4,5] Although, there have been many studies highlighting the risks of ascites for mortality in cirrhotic patients, there have been only limited studies evaluating the consequences of pleural effusion for cirrhotic patients.[6,7,8,9] While patients with ascites can often tolerate up to at least 5-8 L of fluid with only mild symptoms, cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion can experience severe symptoms with as little as 1-2 L of fluid, and sometimes less.[10] There is also a paucity of studies reporting the effects of pleural effusion on mortality in cirrhotic patients.[9]

In this study, we used a nationwide population-based dataset from Taiwan to determine the short- and long-term effects of pleural effusion on mortality in cirrhotic patients and aimed to identify the predictive factors for the long-term mortality.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Database

The secondary de-identified database used in our study was derived from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan, established by Taiwan National Health Insurance Administration. In 1995, Taiwan rolled out the National Health Insurance Program. Currently, the National Health Insurance Board covers >99% of the population in Taiwan. For medical payment, all medical records from all contracted medical institutions are required by the NHIB. This dataset includes all diagnostic coding information of hospitalized patients in Taiwan. The privacy of patients and health care providers was protected. This study was approved by the National Health Research Institute in Taiwan with the application and agreement number 101516. To date, many studies have been published based on this database.[11,12,13,14]

This study was initiated with approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Buddhist Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan (IRB B10104010). The review board in this program waived the requirement for written informed consent from all patients enrolled in this study. In this study, the researchers cannot identify any personal information of patients in this secondary de-identified database.

Study sample

This retrospective study included patients who were discharged with the diagnosis of cirrhosis (International Classification of Diseases, 9thRevision, Clinical Modification code 571.5, or 571.2 in the database; ICD-9-CM) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2007. Each patient was followed individually until December 31, 2010. In this situation, the pleural effusion group was defined as cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage during hospitalization. We used the medical payment code in NHIRD for defining the patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage. In the cases of multiple hospitalizations, only the first episode was enrolled.

In order to analyze the effect of pleural effusion on the mortality of cirrhotic patients, we selected the factors related to the mortality of cirrhotic patients as comorbid medical factors, including alcoholism (ICD-9-CM codes 291, 303, 305.00-305.03, 571.0-571.3), esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) (ICD-9-CM code 456.0, 456.20), pneumonia (ICD-9-CM codes 481-487, without 484), hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (ICD-9-CM code 572.2), heart failure (ICD-9-CM codes 428.0, 428.1,428.9), lung cancer (ICD-9-CM codes 162), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (ICD-9-CM code 155.0), renal function impairment (RFI), ascites, and liver transplantation. Patients with RFI were defined as those with diagnostic codes related to RFI (ICD-9-CM code 584, 585, 586, 572.4, or other procedure codes relate to renal failure).[14] We used the medical payment code in NHIRD for defining the patients with ascites requiring drainage or liver transplantation. To evaluate the early and late effects of liver transplantation on the mortality in cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion, we calculated the mortalities in each period for surviving analysis.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics package (SPSS Inc. Released 2009. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.). The Chi square test was used to compare categorical variables. Student's t-test was used to compare continuous variables. The proportional hazards Cox regression model was used to control for possible confounding factors, including sex, age, HCC, RFI, HE, pneumonia, EVB, alcoholism, liver transplantation, heart failure, lung cancer, and ascites requiring drainage. We presented hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. HR for mortality was calculated for the comparison between the patients with and without liver transplantation. The starting point for evaluating the 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 3-year mortalities in the cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion was the date of admission in the enrolled hospitalizations.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes

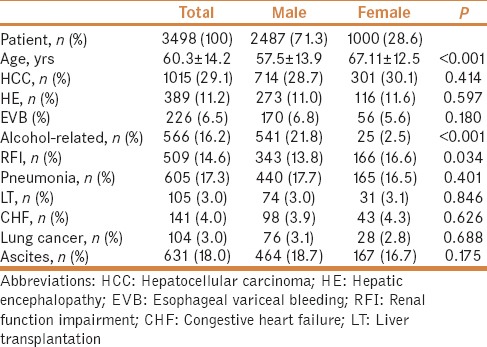

A total of 3,487 cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage were enrolled in this study. Mean age of the patients was 60.3 ± 14.2 years; 71.3% (2,487/3,487) were male. The demographic characteristics and comorbidities of the cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion are shown in Table 1. The 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 3-year mortalities were 20.1%, 40.2%, 59.1%, and 75.9%, respectively, in the cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion. There were 631 (18.0%) patients with ascites requiring drainage, 141 (4.0%) patients with congestive heart failure, 104 (3.0%) with a history of lung cancer, 1015 (29.1%) patients with a history of HCC, 389 (12.2%) patients with HE, 226 (6.5%) patients with bleeding esophageal varices, 605 (17.3%) patients with pneumonia, and 509 (14.6%) patients with RFI. Overall, 105 (3.0%) patients underwent liver transplantation.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of cirrhotic patients having pleural effusion

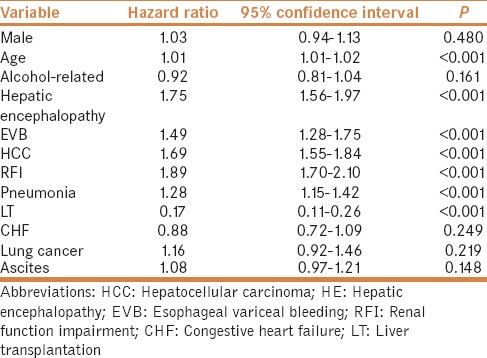

Clinical features associated with 3-year mortality

Table 2 shows the results of Cox proportional regression model analysis, adjusted by age, sex, and other comorbid disorders including heart failure, HCC, EVB, pneumonia, alcoholism, RFI, and HE for the hazard ratios for 3-year mortality in cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage. The HR of the liver transplantation for the 3-year mortalities of cirrhotic patients was 0.17 (95% CI 0.11-0.26, P< 0.001). The RFI, old age, EVB, HCC, pneumonia, and HE conferred higher risks for mortality in the cirrhotic patients. As ascites, heart failure, and lung cancer are important etiological factors for pleural effusion, analysis was done by excluding those patients. After excluding (N = 2684), the 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 3-year mortalities were 19.3%, 38.6%, 60%, and 75.4%, respectively. No difference in mortality was observed at 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 3-year between the cohorts with and without excluding patients (Log-rank test: P = 0.479, 0.486, 0.915, and 0.708, respectively).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for mortality in cirrhotic patients having pleural effusion during the 3-year follow-up period

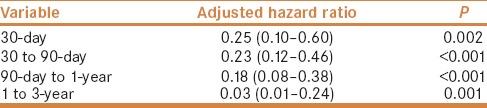

Mortality and cumulative survival after liver transplantation

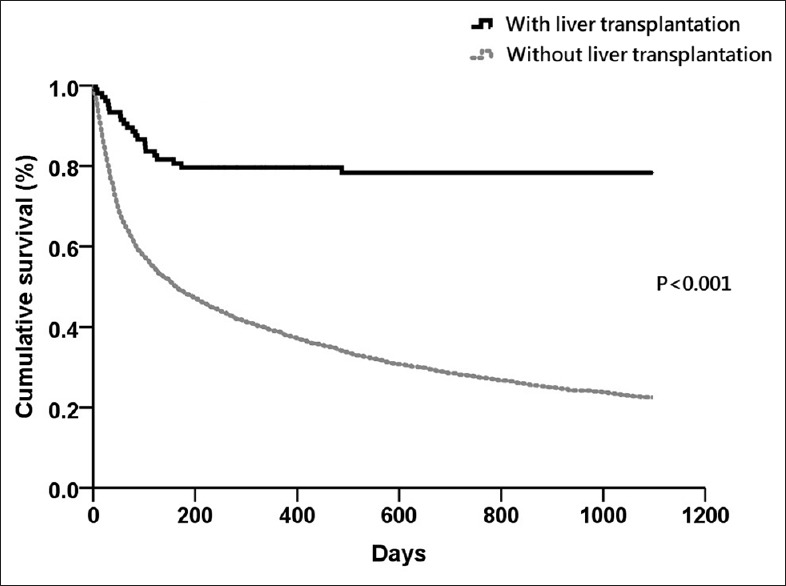

In order to evaluate the early and late effects of liver transplantation on mortality, we also calculated the 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality of the patients surviving more than 30 days, the 1-year mortality of the patients surviving more than 90 days, and 3-year mortality of the patients surviving more than 1 year. The 30-day, 30 to 90-day, 90-day to 1-year, and 1 to 3-year mortalities were 5.7%, 13.4%, 20.4%, and 21.7% respectively, in the liver transplantation group, and 20.5%, 41.0%, 61.2%, and 77.5% respectively, in the non-liver transplantation group. After Cox proportional regression analysis adjusted by age, gender, and other comorbid factors, the HRs for 30-day, 30 to 90-day, 90-day to 1-year, and 1 to 3-year mortalities in patients who accept liver transplantation were 0.25 (95% CI 0.10-0.60, P = 0.002), 0.23 (95% CI 0.12-0.46 P < 0.001), 0.18 (95% CI 0.08-0.38, P < 0.001), and 0.03 (95% CI 0.01-0.24, P = 0.001), respectively, compared to the non-liver transplantation group. [Table 3]. Figure 1 shows the cumulative survival plot for these two groups.

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios of pleural effusion for the 30-day, 30 to 90-day, 90-day to 1-year, 1 to 3-year mortalities of cirrhotic patients with liver transplantation, compared to those without liver transplantation

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion

DISCUSSION

In cirrhotic patients, the incidence of pleural effusion derived from hepatic hydrothorax varies from 16% to 70% according to the criteria of different studies.[9,15] Hepatic hydrothorax has been defined as a pleural effusion, typically of a volume greater than 500 mL, in cirrhotic patients without coexisting cardiopulmonary disease.[16,17,18,19] However, the limitation of this definition is the requirement to exclude other etiologies for the pleural effusion. In clinical practice, cirrhotic patients with cardiopulmonary disease may also develop hepatic hydrothorax because of a diaphragm defect. According to this definition, pleural effusion related to ascites in cirrhotic patients with underlying cardiopulmonary disease would be excluded from most clinical studies. This may indicate a lower incidence than what exists. For example, in one study, 223 of 495 (45.1%) detailed pleural effusion analyses were not available for cirrhotic patients.[9] All these factors may lead to the limited usage of diagnosis criteria to present the hepatic hydrothorax and cannot present the whole view of pleural effusion in cirrhotic patients.

Regarding the etiology of pleural effusion, the presence of fluid in the pleural cavity can affect the respiratory or circulatory system. Unlike ascites where large volumes are generally tolerated due to the large capacitance of the peritoneal cavity, small volumes of about 1-2 L of fluid within the pleural space can lead to significant symptoms.[16] This means the presence of pleural effusion in cirrhotic patients is usually a significant problem, and the risk it presents for the short- and long-term morality should be better understood.

The high mortality of cirrhotic patients with ascites is well known, mostly due to their decompensated status and susceptibility to infectious diseases.[20,21] Compared to studies evaluating the effects of ascites, there are only limited studies that have examined the risk for mortality in cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion.[5,6,7,8,9] Our study highlights the long-term prognosis for cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion and showed the effect of pleural effusions on mortality in the period from 30 days to 3 years after drainage. In clinical situations, cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion usually experience shortness of breath and signs of infection. Cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion may receive thoracentesis for symptom control in the short-term. However, the long-term outcome is a different matter altogether. The long-term outcome of cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion is mostly a consequence of the underlying function of the cirrhotic liver or the underlying cardiopulmonary function. Our study highlights the poor long-term prognosis of cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion, and the presence of pleural effusion requiring drainage should be considered as a negative long-term prognostic factor. The 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 3-year mortalities were 20.1%, 40.2%, 59.1%, and 75.9%, respectively. This finding is compatible with one recent study.[9] Badillo et al. reported that about 10% of patients (8/77) died within 30 days following index hospital admission, and more than half of the patients died within 1 year following presentation with hepatic hydrothorax. According to their report, pleural effusion was regarded as a poor prognostic factor, and the mortality was independent of the Mayo Clinic model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score.[9]

In our study, we also identified the factors associated with the 3-year mortality for cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion. The complications of liver cirrhosis including HE, bleeding esophageal varices, and HCC, were predictive factors for long-term mortality. The comorbidities including old age, pneumonia, and RFI are also risk factors for mortality in cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage. Although ascites, heart failure, and lung cancer are important etiological factors for pleural effusion, these comorbidities were not associated with long-term outcome. Therefore, aggressive treatment is required for patients with decompensated status and multiple comorbidities.

According to our report, liver transplantation is the most important factor to determine the 3-year mortalities (HR: 0.17, 95% CI 0.11-0.26, P < 0.001). Liver transplantation markedly improved the patient outcome and the result was compatible with other studies.[22] One hundred and five patients (105/3487; 3%) underwent liver transplantation. The benefit on the mortality of cirrhotic patients starts within the first 30 days after liver transplantation [Figure 1 and Table 3]. A very impressive plateau in the survival curve was noted after 1 year in the transplantation group. To reverse the poor outcome in cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion, early liver transplantation should be considered.

Therapeutic options for this population include frequent paracentesis, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and liver transplantation.[10,16,19] TIPS is an efficacious treatment for patients for whom transplant is not an immediate option. However, this technique is available only in a few hospitals in Taiwan. After extracting the code of technique fee from the database, no patient underwent this treatment in our study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population-based study reporting the effects of pleural effusion on long-term mortality in cirrhotic patients. Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, although the severity of cirrhosis was commonly based on the Child-Pugh score or MELD score, the laboratory data such as prothrombin time, or albumin, bilirubin, or creatinine levels could not be identified by ICD-9 coding numbers in this database. However, the Cox regression model was used to control for possible confounding factors and make the results significant and robust. Second, the etiology of the pleural effusion or ascites could not be well-evaluated in this study because fluid-analysis data were lacking. However, this study provides an overview of the effect of pleural effusion on the mortality of cirrhotic patients and provides some information for physicians caring for such patients. The large sample size provides the statistical power to detect differences in the mortality risk for cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion, and may provide better information for clinical practice. Third, since the volume of pleural effusion or ascites could not be quantified in this database, the study only enrolled cirrhotic patients requiring drainage. Cirrhotic patients with minimal pleural effusion or ascites would not have been included in this study. Therefore, the mortality rate might be overestimated in this cohort. Further studies may be needed to evaluate the long-term outcomes of cirrhotic patients with mild or transient pleural effusion. Fourth, the causes of death were not available in our dataset. Due to the high cirrhosis mortality rate in this population, we can suppose that most causes of death were related to the liver disease. Despite these limitations, this nationwide population-based study identified the mortality risk associated with pleural effusion requiring drainage in cirrhotic patients.

CONCLUSION

In summary, cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion have a high long-term mortality, and physicians should be aware of the high mortality of these patients. Liver transplantation could dramatically improve survival in cirrhotic patients with pleural effusion. Early liver transplantation may be an appropriate option for such patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was based in part on data from the NHIRD provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, and managed by National Health Research Institutes (Registered number: 101516). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, or National Health Research Institutes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernández-Esparrach G, Sánchez-Fueyo A, Ginès P, Uriz J, Quintó L, Ventura PJ, et al. A prognostic model for predicting survival in cirrhosis with ascites. J Hepatol. 2001;34:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thuluvath PJ, Morss S, Thompson R. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis--in-hospital mortality, predictors of survival, and health care costs from 1988 to 1998. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1232–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheong HS, Kang CI, Lee JA, Moon SY, Joung MK, Chung DR, et al. Clinical significance and outcome of nosocomial acquisition of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1230–6. doi: 10.1086/597585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kathpalia P, Bhatia A, Robertazzi S, Ahn J, Cohen SM, Sontag S, et al. Indwelling peritoneal catheters in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Intern Med J. 2015;45:1026–31. doi: 10.1111/imj.12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirouze D, Juttner HU, Reynolds TB. Left pleural effusion in patients with chronic liver disease and ascites. Prospective study of 22 cases. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:984–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01314759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luh SP, Chen CY. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for the treatment of hepatic hydrothorax: Report of twelve cases. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009;10:547–51. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orman ES, Lok AS. Outcomes of patients with chest tube insertion for hepatic hydrothorax. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:582–6. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9136-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badillo R, Rockey DC. Hepatic hydrothorax: Clinical features, management, and outcomes in 77 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:135–42. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardenas A, Kelleher T, Chopra S. Review article: Hepatic hydrothorax. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:271–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hung TH, Tseng CW, Tseng KC, Hsieh YH, Tsai CC, Tsai CC. Effect of renal function impairment on the mortality of cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy: A population-based 3-year follow-up study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e79. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu PH, Lin YT, Kuo CN, Chang WC, Chang WP. No increased risk of herpes zoster found in cirrhotic patients: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng CY, Ho CH, Wang CC, Liang FW, Wang JJ, Chio CC, et al. One-year mortality after traumatic brain injury in liver cirrhosis patients—A ten-year population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1468. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung TH, Tsai CC, Hsieh YH, Tsai CC, Tseng CW, Tsai JJ. Effect of renal impairment on mortality of patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:677–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiol X, Castellote J, Cortes-Beut R, Delgado M, Guardiola J, Sesé E. Usefulness and complications of thoracentesis in cirrhotic patients. Am J Med. 2001;111:67–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiafar C, Gilani N. Hepatic hydrothorax: Current concepts of pathophysiology and treatment options. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:313–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krok KL, Cárdenas A. Hepatic hydrothorax. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:3–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1301729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machicao VI, Balakrishnan M, Fallon MB. Pulmonary complications in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59:1627–37. doi: 10.1002/hep.26745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norvell JP, Spivey JR. Hepatic hydrothorax. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:439–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perdomo Coral G, Alves de Mattos A. Renal impairment after spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Incidence and prognosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:187–90. doi: 10.1155/2003/370257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Renal dysfunction is the most important independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russo FP, Ferrarese A, Zanetto A. Recent advances in understanding and managing liver transplantation. F1000Res. 2016;5 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8768.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]