Summary

We describe a large cluster of urethritis due to a distinct nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis clade (ST-11 clonal complex) among mostly black, heterosexual males in Columbus, Ohio. The cluster was first noticed in 2015 through routine surveillance for Neisseria gonorrhoeae urethritis.

Keywords: Neisseria meningitidis, urethritis, Gram stain, Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Abstract

Background

Neisseria meningitidis (Nm) is a Gram-negative diplococcus that normally colonizes the nasopharynx and rarely infects the urogenital tract. On Gram stain of urethral exudates, Nm can be misidentified as the more common sexually transmitted pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Methods

In response to a large increase in cases of Nm urethritis identified among men presenting for screening at a sexually transmitted disease clinic in Columbus, Ohio, we investigated the epidemiologic characteristics of men with Nm urethritis and the molecular and phylogenetic characteristics of their Nm isolates. The study was conducted between 1 January and 18 November 2015.

Results

Seventy-five Nm urethritis cases were confirmed by biochemical and polymerase chain reaction testing. Men with Nm urethritis were a median age of 31 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 24–38) and had a median of 2 sex partners in the last 3 months (IQR = 1–3). Nm cases were predominantly black (81%) and heterosexual (99%). Most had urethral discharge (91%), reported oral sex with a female in the last 12 months (96%), and were treated with a ceftriaxone-based regimen (95%). A minority (15%) also had urethral chlamydia coinfection. All urethral Nm isolates were nongroupable, ST-11 clonal complex (cc11), ET-15, and clustered together phylogenetically. Urethral Nm isolates were similar by fine typing (PorA P1.5-1,10-8, PorB 2-2, FetA F3-6), except 2, which had different PorB types (2-78 and 2-52).

Conclusions

Between January and November 2015, 75 urethritis cases due to a distinct Nm clade occurred among primarily black, heterosexual men in Columbus, Ohio. Future urogenital Nm infection studies should focus on pathogenesis and modes of sexual transmission.

Neisseria meningitidis (Nm) is a Gram-negative diplococcus that colonizes the nasopharynx of approximately 11% of individuals and can cause invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), including bacterial meningitis and septicemia [1, 2]. High nasopharyngeal carriage rates have been reported among those aged 15–19 years (25%) and in men who have sex with men (MSM) attending sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics (43%) [2, 3]. Although most IMD cases are caused by encapsulated strains (serogroup A, B, C, Y, X, and W), a significant proportion of nasopharyngeal Nm carriage strains do not express a capsule (nongroupable [NmNG]) [4–6].

Infrequently, Nm is isolated from urethral cultures (prevalence estimates = 0.1%–0.7%) [3, 7, 8]. Men who receive oral sex (fellatio) from partners colonized with Nm in the nasopharynx may acquire urethral Nm infection [9, 10]. On Gram stain of urethral exudates, Nm can be misidentified as the more common sexually transmitted pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) because both present as Gram-negative intracellular diplococci (GNID) [9–12].

No US surveillance program systematically captures urethral Nm infections. However, from 1 January to 18 November 2015, we identified 75 men with urethritis caused by a distinct Nm clade at the public STD clinic in Columbus, Ohio. Neisseria meningitidis urethritis was an incidental finding detected during routine screening for urethral GC infection as part of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) [13]. No documented cases of Nm urethritis occurred at the same STD clinic in 2014. Such a large molecularly linked cluster of Nm urethritis cases has not been previously described, and the existence of this cluster raises questions about the sexual transmission of Nm. Our objective was to describe the epidemiologic characteristics of the infected men and define the molecular and phylogenetic characteristics of the urethral Nm isolates.

METHODS

Urethritis Screening and Treatment

All men who present to the STD clinic in Columbus, Ohio, have a urethral swab collected regardless of symptoms. Presence of urethral GNID is interpreted as presumptive GC urethritis [14]. Urine is also obtained for GC and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) nucleic-acid amplification testing (NAAT; APTIMA Combo2 Assay, Hologic, Inc, Marlborough, MA) and Trichomonas vaginalis culture (modified Trichosel broth with 5% horse serum; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Patients with a presumptive diagnosis of GC urethritis are treated with a CDC-recommended regimen [14] at presentation and before urine NAAT and culture results are finalized.

Urethral Cultures for Neisseria gonorrhoeae

The STD clinic in Columbus, Ohio, is a sentinel site for the CDC’s GISP, which monitors GC antimicrobial susceptibility trends in the United States [13]. According to GISP and Columbus STD clinic protocols, urethral swabs from male patients with GNID are inoculated onto modified Thayer-Martin media and incubated at 37°C in a 3%–10% carbon dioxide–enriched atmosphere for up to 72 hours. Oxidase-positive colonies with Gram-negative diplococci are presumed to be GC and subsequently undergo antimicrobial susceptibility testing at a GISP reference laboratory [13].

Identification and Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis

Oxidase-positive colonies (Gram-negative diplococci) from patients with urethral GNID, but negative urine NAATs for GC, were sent to the CDC’s Bacterial Meningitis Laboratory for identification using Analytical Profile Index Neisseria-Haemophilus (API NH) strip biochemical testing (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and species-specific superoxide dismutase gene (sodC) real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) [15]. Slide agglutination serogrouping and rt-PCR targeting serogroup-specific genes in the capsule locus (cps) [16, 17] were performed on all urethral Nm isolates. The cps locus was further examined by overlapping PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

All urethral Nm isolates underwent whole-genome sequencing using Illumina technology (see Supplementary Appendix). Genomes were assembled from Illumina data with CLC Genomics Workbench, version 8.0.2 (CLC bio, Aaarhus, Denmark). Final assemblies were submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information under BioProject PRJNA324131.

Genotyping

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed by searching assembled genomes with PubMLST allele lists [18] using BLAST (http://neisseria.org/nm/typing/mlst/). Outer membrane protein (OMP) gene sequences, including serogroup B vaccine antigens, were typed according to PubMLST sequence collection. Porin A (porA), porin B (porB), and ferric enterobactin transport (fetA) were typed according to their respective variable regions, Neisseria adhesin A (nadA) was categorized by the Novartis convention of variant and peptide ID [19], and both Neisserial heparin binding antigen (nhba) and factor H binding protein (fHbp) were identified by PubMLST peptide identifier.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The urethral Nm isolates were compared against 1482 published sequence type (ST)–11 clonal complex (cc11) genomes downloaded from PubMLST.org on 21 January 2016 [18]. The maximum likelihood phylogeny was inferred from core single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood (RAxML) v8.2.4 [20], with the Generalized Time Reversible (GTR) GAMMAX substitution model and autoMRE “bootstopping.” Core SNPs were identified using kSNP3 [21] and Harvest v1.1.2 [22] (see Supplementary Appendix).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Minimum inhibitory concentrations by broth microdilution were determined for penicillin, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, rifampin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints for Nm were defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [23].

Data Collection and Extraction

Demographic, behavioral, clinical, laboratory, and travel data for all cases of Nm urethritis and culture-positive GC urethritis diagnosed at the STD clinic between 1 January and 18 November 2015 were extracted from electronic medical records (EMRs). Behavioral variables from self-administered intake forms, completed at each visit, were also extracted. Meningococcal vaccination status for Nm urethritis cases was extracted from Ohio’s IMPACT Statewide Immunizations Information System.

Statistical Analysis

Data extracted from the EMR for Nm urethritis cases were examined. Because the suspected route of Nm transmission to the urethra has been reported to be oral sex [9, 10], we examined multiple different measures of oral sex obtained through clinician interviews and self-administered intake forms, including separate items capturing whether patients performed oral sex, had oral sex with a male, and had oral sex with a female in the last 12 months. We used SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC) to compare men with Nm urethritis to those with culture-positive GC urethritis. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests; medians of continuous variables were compared using Mann-Whitney tests. We set the threshold for statistical significance at α = .05.

Ethical Approval

This project was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Isolation of Urethral Neisseria meningitidis

No instances of urethritis with GNID, growth of oxidase-positive Gram-negative diplococci, and negative urine NAAT for GC were identified during January–November 2014. In December 2014, we identified 3 such cases. No additional identification testing of these isolates was performed. However, during the period 1 January–18 November 2015, 76 urethritis cases with similar patterns of urethral Gram-stain, culture, and urine NAAT results were observed. Seventy-five of 76 urethral isolates were subsequently confirmed to be Nm by API NH and species-specific rt-PCR; one urethral isolate was confirmed as GC. During the same period, 297 culture-positive urethral GC cases were identified; all had urethral GNID and positive urine NAAT for GC (Figure 1). Overall, 20% of men with urethral GNID and growth of oxidase-positive Gram-negative diplococci had urethral Nm.

Figure 1.

Number of male patients with confirmed Neisseria meningitidis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae urethritis, Columbus, Ohio, January 1–November 18, 2015 (n = 372). *Through November 18 only. Abbreviations: GC, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; Nm, Neisseria meningitidis.

Patient Characteristics

We observed no significant differences in age, race, or ethnicity between men with Nm and GC urethritis (Table 1). Majorities in both groups were black (81% [Nm] and 71% [GC]) and non-Hispanic (91% [Nm] and 92% [GC]). A significantly greater proportion of men with Nm urethritis identified as heterosexual, compared with men with GC urethritis (99% [Nm] vs 78% [GC], P < .01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Male Patients With Nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae Urethritis, Columbus, Ohio, 1 January–18 November 2015 (n = 372)

| Patient characteristics | Nma cases | GCb cases | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raced | |||

| White | 11 (15) | 68 (23) | .12 |

| Black | 61 (81) | 212 (71) | .08 |

| Othere | 5 (7) | 27 (9) | .50 |

| Ethnicity | .42 | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 68 (91) | 272 (92) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (5) | 8 (3) | |

| Missing | 3 (4) | 17 (6) | |

| Sexual orientation | <.01 | ||

| Heterosexual | 74 (99) | 233 (78) | |

| Homosexual | 1 (1) | 57 (19) | |

| Bisexual | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | |

| Relationship status | .25 | ||

| Single | 52 (69) | 212 (71) | |

| Married/partnered | 6 (8) | 30 (10) | |

| Divorced/legally separated/ widowed | 10 (13) | 19 (6) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 36 (12) | |

| Highest schooling completed | .18 | ||

| Less than high school | 6 (8) | 32 (11) | |

| Finished high school/GED | 37 (49) | 119 (40) | |

| At least some college | 28 (37) | 107 (36) | |

| Missing | 4 (5) | 39 (13) | |

| How often do you use a condom? | .69 | ||

| Always | 13 (17) | 50 (17) | |

| Sometimes | 53 (71) | 219 (74) | |

| Never | 6 (8) | 14 (5) | |

| Missing | 3 (4) | 14 (5) | |

| Performed oral sex (last 12 months), clinician interviewf | .44 | ||

| Yes | 49 (65) | 200 (68) | |

| No | 25 (33) | 84 (28) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 13 (4) | |

| Oral sex with a female (last 12 months), clinician interviewf,g | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 72 (96) | 215 (73) | |

| No | 1 (1) | 53 (18) | |

| Missing | 2 (3) | 29 (9) | |

| Oral sex with a male (last 12 months), clinician interviewf,g | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 2 (3) | 60 (20) | |

| No | 71 (94) | 208 (70) | |

| Missing | 2 (3) | 29 (10) | |

| Oral sex with a female (last 12 months), self-administered intake formg,h | .02 | ||

| Yes | 54 (72) | 176 (59) | |

| No | 13 (17) | 101 (34) | |

| Missing | 8 (11) | 20 (7) | |

| Oral sex with a male (last 12 months), self-administered intake formg,h | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 2 (3) | 61 (21) | |

| No | 66 (88) | 216 (73) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 20 (7) | |

| Vaginal sex with a female (last 12 months) | .07 | ||

| Yes | 59 (79) | 206 (69) | |

| No | 9 (12) | 71 (24) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 20 (7) | |

| Sex with an HIV-positive partner (last 12 months) | .07 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 18 (6) | |

| No | 68 (91) | 250 (84) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 29 (10) | |

| Sex with an anonymous partner (last 12 months) | .73 | ||

| Yes | 20 (27) | 93 (31) | |

| No | 48 (64) | 180 (61) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 24 (8) | |

| Sex with an IV drug user (last 12 months) | .73 | ||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 15 (5) | |

| No | 62 (83) | 256 (86) | |

| Missing | 8 (11) | 26 (9) | |

| Sex while high on alcohol (last 12 months) | .73 | ||

| Yes | 28 (37) | 126 (42) | |

| No | 40 (53) | 146 (49) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 25 (8) | |

| Sex while high on drugs (last 12 months) | .82 | ||

| Yes | 18 (24) | 81 (27) | |

| No | 50 (67) | 192 (65) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 24 (8) | |

| Exchanged sex for drugs/money (last 12 months) | .96 | ||

| Yes | 3 (4) | 14 (5) | |

| No | 65 (87) | 258 (87) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 25 (8) | |

| Used injection drugs (last 12 months) | .93 | ||

| Yes | 1 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| No | 67 (89) | 268 (90) | |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 25 (8) | |

| HIV status (n = 335)i | .14 | ||

| Positive | 1 (1) | 17 (6) | |

| Negative | 71 (99) | 246 (94) | |

| Gonorrhea (oral; n = 244)j | .05 | ||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 18 (9) | |

| Negative | 45 (100) | 181 (91) | |

| Gonorrhea (rectal; n = 40)j | .35 | ||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 26 (67) | |

| Negative | 1 (100) | 13 (33) | |

| Chlamydia (urethral; n = 370)j | .09 | ||

| Positive | 11 (15) | 71 (24) | |

| Negative | 63 (85) | 225 (76) | |

| Chlamydia (rectal; n = 41)j | 1.00 | ||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | |

| Negative | 1 (100) | 37 (93) | |

| Syphilis (n = 369)j | 1.00 | ||

| Positive | 1 (1) | 7 (2) | |

| Negative | 74 (99) | 287 (98) | |

| Trichomoniasis (n = 322)j | .58 | ||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | |

| Negative | 74 (100) | 244 (98) | |

| Symptoms | .86 | ||

| Any | 74 (99) | 286 (96) | |

| None | 1 (1) | 7 (2) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | |

| Types of symptomsd | |||

| Urethral discharge | 68 (91) | 275 (93) | .43 |

| Dysuria | 51 (68) | 217 (73) | .43 |

| Otherk | 3 (4) | 11 (4) | 1.00 |

| Travel outside of Ohio (last 60 days) | .29 | ||

| Yesl | 6 (8) | 43 (14) | |

| No | 64 (85) | 240 (81) | |

| Missing | 5 (7) | 14 (5) | |

| Treatment provided | .39 | ||

| Ceftriaxone plus azithromycin | 69 (92) | 273 (92) | |

| Ceftriaxone plus doxycycline | 2 (3) | 11 (4) | |

| Ceftriaxone alone | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Azithromycin alone | 3 (4) | 13 (4) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 31 (24–38) | 28 (23–38) | .20 |

| No. of partners (90 days) (n = 359), median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–4) | .02 |

| No. of partners (12 months) (n = 270), median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) | 3 (2–5) | .01 |

| No. of days since last sexual encounter (n = 305), median (IQR) | 7 (3–10) | 6 (4–9) | .29 |

| Number of days with symptoms (n = 341), median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (3–7) | .43 |

Data are no. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: GC, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; IV, intravenous; Nm, Neisseria meningitidis.

aNongroupable N. meningitidis cases confirmed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Bacterial Meningitis Laboratory.

b Neisseria gonorrhoeae cases determined by urine nucleic-acid amplification testing at Columbus Public Health’s sexually transmitted disease clinic laboratory.

c P values for categorical variables are from χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests (when cell counts are <5); P values comparing medians of continuous variables are from Mann-Whitney tests.

dPatients could select >1 category, so categories total >100%; P values are calculated for individual categories.

eOther includes Asian (Nm = 0, GC = 3), American Indian (Nm = 1, GC = 8), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (Nm = 0, GC = 6), and unidentified other (Nm = 4, GC = 14).

fEntered into the electronic medical record by clinician.

gOral sex may include performing or receiving.

hScanned into the electronic medical record.

iPositive includes individuals who previously tested positive (Nm = 1, GC = 14) or tested positive on the date of service by HIV rapid test (Nm = 0, GC = 3). Negative includes individuals with a negative HIV rapid test on the date of service.

jDiagnosis of primary, secondary, or latent syphilis that required treatment. Numbers include only individuals who received testing on the date of Nm or GC diagnosis.

kIncludes blister, bump, lesion, rash, sore, rectal pain, or pelvic pain.

lTravel locations for patients with Nm urethritis who reported travel (n = 6): Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (n = 1), New York City, New York (n = 1), Chicago, Illinois (n = 1), West Virginia (n = 1), and Miami, Florida (n = 2).

Sexual Behaviors

Sexual behaviors varied somewhat between Nm and GC urethritis cases (Table 1). Reported prevalence of oral sex was higher when ascertained during the clinician interview compared with self-report on the intake form. Regardless of ascertainment method, Nm urethritis cases reported oral sex with a female partner more often than GC urethritis cases (clinician interview: 96% [Nm] vs 73% [GC], P < .01; intake form: 72% [Nm] vs 59% [GC], P = .02). When restricted to men reporting sex with women (99% of Nm cases and 80% of GC cases), there was no significant difference in the proportions of Nm and GC urethritis cases reporting oral sex with a woman in the last year. In this restricted sample, there was also no difference in the proportion of Nm and GC urethritis cases reporting vaginal sex in the last year (data not shown).

Sexually Transmitted Disease Coinfections

The proportion of men with urethral and rectal CT, trichomoniasis, syphilis, and HIV was similar in both groups (Table 1). Men with GC urethritis more often had oropharyngeal GC infection compared with men with Nm urethritis (9% [GC] vs 0% [Nm], P = .05).

Presenting Symptoms and Treatment

Most men in both groups reported urethral discharge (91% [Nm] and 93% [GC]). Both groups reported similar time since last sex (median: 7 days [Nm] and 6 days [GC]; P = .29) and similar duration of symptoms prior to seeking care (median: 4 days [Nm] and 4 days [GC]; P = .43). Nearly all men received CDC-recommended dual therapy for GC (single 250-mg dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone and single 1-g dose of oral azithromycin) (Table 1) [14]. Per STD clinic protocol, men were advised to rescreen in 3 months. To the best of our knowledge, no treatment failures occurred during the study period.

Meningococcal Vaccination Status

Meningococcal vaccination data were incomplete for men with Nm urethritis. Only 8 (11%) vaccinated individuals were identified: All received at least 1 dose of the quadrivalent (A, C, Y, and W) conjugate vaccine Menactra (Sanofi Pasteur, Inc).

Characterization of Urethral Neisseria meningitidis Isolates

Serogrouping

None of the 75 urethral Nm isolates had evidence of capsule expression by slide agglutination serogrouping (NG phenotype). However, serogroup-specific rt-PCR yielded conflicting results. All isolates were negative for serogroups A, B, C, W, X, and Y by the method of Wang et al [16]. In contrast, the serogroup C capsule polymerase gene (csc) was identified by the method of Bennett and Cefferkey [17].

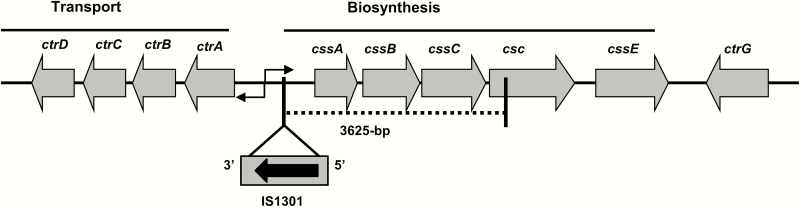

Further analysis of the cps locus identified only 860 nucleotides from the 3ʹ end of the 1479 nucleotide open reading frame of the csc. Primer F478 from Wang et al [16] binds between positions 591 and 610 of csc, which is within the first 619 nucleotides that are absent in these isolates. Overlapping PCR and sequencing of the cps locus revealed insertion of an intact IS1301 element into the intergenic region of the capsule transport (ctr) and sialic-acid capsule biosynthesis (css) operons and deletion of 3625 base pairs, including the cssABC genes and 5’-region of csc (Figure 2). The IS1301 element is associated with insertion/deletion events at the cps locus [6, 24]. Absence of the cssABC genes and 5’-region of csc was confirmed by whole-genome sequencing data and explain the NG phenotype of the urethral Nm isolates.

Figure 2.

Configuration of the capsule locus (cps) in the nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis urethral isolates (Columbus, Ohio). An 843-bp insertion element (IS1301) was present in the intergenic region linking the ctr and css operons with simultaneous deletion of cssABC genes and partial csc (5’-region) (dotted line). Abbreviations: ctrG, capsule surface translocation gene; csc, serogroup C capsule polymerase (polysialyltransferase) gene; cssA-C, sialic-acid capsule biosynthesis genes; cssE, O-acetyltransferase gene; ctrA-D, capsule transport genes.

Genotyping

All 75 urethral Nm isolates belong to the ST-11 clonal complex (cc11) and were PorA type P1.5,-1,10-8 and FetA type F3-6. Seventy-three isolates were PorB type 2-2, one isolate was PorB type 2-78, and one isolate was PorB type 2-52. Analysis of the fumarase gene (fumC) sequence in all isolates revealed the G-to-A polymorphism (position 667) that is characteristic of the electrophoretic type (ET)–15 hypervirulent variant [25]. All isolates encode NHBA-20 and fHbp-v1/subfamily B (novel peptide sequence; PubMLST ID = 896) [26, 27]. Seventy-one isolates encoded NadA-2/3.2 [19], whereas 4 assemblies contained disrupted nadA that could not be assembled, 3 of which were confirmed using ISMapper [28] to be due to an insertion of IS1301.

Phylogenetic Analysis

All 75 urethral Nm isolates formed a monophyletic clade containing none of the 1482 published cc11 genomes (Figure 3). The most closely related published genome was from an NmNG isolate associated with IMD, whereas other closely related genomes were from invasive serogroup C isolates in the 11.2/ET-15 lineage [29].

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic placement of nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis (Nm) urethral isolates (Columbus, Ohio) among closely related Nm cc11 isolates. Previously published isolates are labeled according to disease type, serogroup, country, and year of isolation, with isolate name and PubMLST identifier in parentheses. Asterisks indicate that the year of isolation was not available for a published genome sequence. Isolates from this study are labeled by their month of isolation in 2015. Isolates on branches representing fewer than 10–5 substitutions per site are grouped with others from the same month, and their count is reported in brackets. The phylogeny is inferred from a 1.45-megabase core genome alignment and rooted on the remainder of Nm cc11. Branches with bootstrap support <80% were collapsed, with unlabeled branches having 100% bootstrap support (400 replicates). Abbreviation: NG, nongroupable.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

In a convenience sample of 12 urethral Nm isolates (data not shown), all were susceptible to ceftriaxone, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, rifampin, and trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, and all had intermediate susceptibility to penicillin and ampicillin.

DISCUSSION

From 1975 to 1979, Faur et al reported the recovery of 964 urogenital and rectal Nm isolates (variety of serogroups) from men and women in a New York City GC screening program [30]. However, Nm urethritis has historically been an infrequent occurrence [3, 7, 8]. Indeed, the STD clinic where this cluster occurred had no documented cases of Nm urethritis in the year prior and only 3 possible cases. To our knowledge, this represents the largest molecularly linked cluster of Nm urethritis cases: all isolates were NG, ST-11 clonal complex, ET-15 variant, and monophyletic within cc11. The emergence of this cluster raises important questions about the ability of this Nm clade to cause urogenital disease and spread sexually similar to GC.

The ability of Nm to adapt to different environments or selective pressures through phase and antigenic variation is well recognized [1]. The Nm capsule, coded by the cps locus, is an important virulence factor associated with IMD [1, 4]. However, capsule is not required for person-to-person transmission through respiratory secretions and is not present in a substantial proportion of NmNG strains in nasopharyngeal carriage studies [5, 6]. Loss of capsule expression can enhance mucosal attachment by exposing surface opacity adhesins and increasing cell-surface hydrophobicity [1, 31]. The Nm clade described in this cluster had a signature IS1301 insertion/deletion event at the cps locus that resulted in loss of serogroup C capsule expression (Figure 2). We suspect that this genetic event and its resultant phenotype could facilitate attachment to the urethral mucosa. It is also possible that other genotypic and phenotypic changes could contribute to this Nm clade’s evolution into a more effective urogenital tract pathogen. Work by Taha et al suggests that functional expression of AniA nitrite reductase, which enables nitrite-dependent anaerobic growth, could allow Nm to thrive in the urogenital tract [32]. Future work will determine the anaerobic growing capabilities of the Nm clade involved in this cluster.

Based on existing literature, urethral Nm infection likely results from index patients receiving fellatio from partners with nasopharyngeal colonization with Nm [9, 10]. Oral sex was a commonly reported participant behavior. However, variability in the endorsement of oral sex—depending on how the data were collected—demonstrates 1 limitation of extracting behavioral data from EMR. Whether the Nm clade in this cluster is being transmitted through vaginal or anal sex is not known. Furthermore, it is not clear why Nm urethritis became so much more prevalent among heterosexual STD clinic attendees in 2015 or whether our findings can be extrapolated to a non–STD clinic patient population.

Because GISP sentinel sites only culture male urethral specimens to identify GC [13], all Nm urethritis cases identified in this cluster were men. No systematic tracking of sex partners occurred during the study period. Therefore, the size and density of the cluster, including the possibility of a larger sexual network, are unknown. However, other US sites, including Oakland County (Michigan), Philadelphia, and Indianapolis, have also reported an increase in Nm urethritis cases among heterosexual men [12, 33, 34]. Of the urethral Nm isolates tested, 92% (n = 11/12) from Oakland County, 95% (n = 19/20) from Philadelphia, and 100% (n = 2/2) from Indianapolis clustered with the Columbus Nm clade (12, 33, 34; CDC, personal communication). From the 6 men with Nm urethritis in Columbus that reported travel outside of Ohio in the last 60 days (Table 1), 1 visited Philadelphia but none reported travel to Oakland County or Indianapolis.

The apparent lack of involvement of MSM is somewhat surprising, given that MSM attending STD clinics have high rates of nasopharyngeal Nm colonization [3]. Men who have sex with men attending the same public STD clinic in Columbus frequently engage in fellatio [35], which may increase their risk for Nm urethritis. In addition, recent outbreaks of IMD due to Nm serogroup C, including ST-11 clonal complex, have also been reported among MSM in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Southern California [36, 37].

It is theoretically possible that another organism caused urethritis in these men and that Nm is simply a highly prevalent urethral colonizer. Chlamydia trachomatis commonly causes urethritis [38] but was identified as a coinfection in only 15% of the Nm cases. Testing for Mycoplasma genitalium, another cause of urethritis [38], was not performed. Although such testing might be helpful in future studies, it seems highly unlikely that the consistent, highly prevalent symptoms of infected men—all of whom carry the same Nm clade—are instead caused by an alternative urethral pathogen.

No studies have examined optimal treatment of Nm urethritis [39]. In this study, most cases were treated as presumptive GC on the day of presentation with a recommended ceftriaxone-based regimen [14]. Based on the antimicrobial susceptibilities of 12 urethral Nm isolates from the same clade and the fact that no treatment failures came to our attention during the study period, these antibiotic regimens appear to also be effective for the treatment of Nm urethritis.

We are not aware of any IMD cases due to the Nm clade that is causing urethritis in Columbus and suspect that capsule loss has likely attenuated its ability to cause IMD. Vaccination is the primary intervention to prevent IMD, but polysaccharide-based vaccines target the Nm capsule [1, 4], which is absent in this Nm clade. However, protein-antigen vaccines might confer a benefit [40]. The Nm clade described in this cluster contains genomic sequences encoding multiple OMP that may be recognized by serogroup B vaccine components, including an allele of the fHbp protein belonging to variant 1 (4CMenB, Bexsero, Novartis) and subfamily B (MenB-fHbp, Trumenba, Pfizer) [26, 27]. Additional research is needed to determine whether these proteins are expressed sufficiently and whether protein-antigen vaccines can elicit protective antibody levels against this Nm clade at mucosal surfaces.

In summary, the STD clinic in Columbus, Ohio, is experiencing an ongoing cluster of urethritis due to a distinct Nm clade (NG, ST-11 clonal complex, ET-15 variant) among mostly black heterosexual men. As of December 2016, we have identified 47 additional cases of urethritis in men due to the same Nm clade. Until more data are available, suspected or confirmed Nm urethritis cases and their partners are being treated as recommended for GC [12, 14, 39]. Additional research into this Nm clade should focus on the pathogenesis and prevalence of urogenital and extragenital infections, genotypic and phenotypic determinants that may enhance urogenital infection, and modes of sexual transmission in men and women.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the following individuals: Baderinwa Offutt, Tamayo Barnes, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia; Patricia DiNinno, Public Health Laboratory, Columbus Public Health, Columbus, Ohio; Kathy Cowen, MS, Elizabeth Koch, MD, Center for Epidemiology, Preparedness and Response, Columbus Public Health, Columbus, Ohio; Mary DiOrio, MD, MPH, Ohio Department of Health; Jessica R. MacNeil, MPH, Stacey W. Martin, MSc, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; Elizabeth A. Torrone, PhD, Virginia B. Bowen, PhD, Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC; William C. Miller, MD, PhD, MPH, The Ohio State University College of Public Health.

Disclaimers. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial Support. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R21AI128313 and R01AI107116 to Y. L. T.) and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5NH25PS004311 to C. D. R.).

Potential conflict of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Stephens DS. Biology and pathogenesis of the evolutionarily successful, obligate human bacterium Neisseria meningitidis. Vaccine 2009; 27suppl 2:B71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cartwright KA, Stuart JM, Jones DM, Noah ND. The Stonehouse survey: nasopharyngeal carriage of meningococci and Neisseria lactamica. Epidemiol Infect 1987; 99:591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Janda WM, Bohnoff M, Morello JA, Lerner SA. Prevalence and site-pathogen studies of Neisseria meningitidis and N gonorrhoeae in homosexual men. JAMA 1980; 244:2060–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harrison OB, Claus H, Jiang Y, et al. Description and nomenclature of Neisseria meningitidis capsule locus. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Claus H, Maiden MC, Maag R, Frosch M, Vogel U. Many carried meningococci lack the genes required for capsule synthesis and transport. Microbiology 2002; 148(pt 6):1813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dolan-Livengood JM, Miller YK, Martin LE, Urwin R, Stephens DS. Genetic basis for nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis. J Infect Dis 2003; 187:1616–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKenna JG, Fallon RJ, Moyes A, Young H. Anogenital non-gonococcal neisseriae: prevalence and clinical significance. Int J STD AIDS 1993; 4:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maini M, French P, Prince M, Bingham JS. Urethritis due to Neisseria meningitidis in a London genitourinary medicine clinic population. Int J STD AIDS 1992; 3:423–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilson AP, Wolff J, Atia W. Acute urethritis due to Neisseria meningitidis group A acquired by orogenital contact: case report. Genitourin Med 1989; 65:122–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Urra E, Alkorta M, Sota M, et al. Orogenital transmission of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C confirmed by genotyping techniques. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005; 24:51–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Katz AR, Chasnoff R, Komeya A, Lee MV. Neisseria meningitidis urethritis: a case report highlighting clinical similarities to and epidemiological differences from gonococcal urethritis. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bazan JA, Peterson AS, Kirkcaldy RD, et al. Notes from the field: increase in Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis among men at two sentinel clinics—Columbus, Ohio, and Oakland County, Michigan, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:550–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CDC. Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Program (GISP) protocol, updated May 2016 http://www.cdc.gov/std/gisp/gisp-protocol-may-2016.pdf Accessed 11 May 2016.

- 14. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dolan Thomas J, Hatcher CP, Satterfield DA, et al. sodC-based real-time PCR for detection of Neisseria meningitidis. PLoS One 2011; 6:e19361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang X, Theodore MJ, Mair R, et al. Clinical validation of multiplex real-time PCR assays for detection of bacterial meningitis pathogens. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:702–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bennett DE, Cafferkey MT. Consecutive use of two multiplex PCR-based assays for simultaneous identification and determination of capsular status of nine common Neisseria meningitidis serogroups associated with invasive disease. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:1127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jolley KA, Maiden MC. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bambini S, De Chiara M, Muzzi A, et al. Neisseria adhesin a variation and revised nomenclature scheme. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014; 21:966–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gardner SN, Slezak T, Hall BG. kSNP3.0: SNP detection and phylogenetic analysis of genomes without genome alignment or reference genome. Bioinformatics 2015; 31:2877–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol 2014; 15:524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fifth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S25. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tzeng YL, Thomas J, Stephens DS. Regulation of capsule in Neisseria meningitidis. Crit Rev Microbiol 2015; 19:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vogel U, Claus H, Frosch M, Caugant DA. Molecular basis for distinction of the ET-15 clone within the ET-37 complex of Neisseria meningitidis. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38:941–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics S.r.l. (2015). Bexsero®: Prescribing Information https://www.gsksource.com/pharma/content/dam/GlaxoSmithKline/US/en/Prescribing_Information/Bexsero/pdf/BEXSERO.PDF Accessed 16 July 2016.

- 27. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Trumenba®: Prescribing Information http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=1796 Accessed 16 July 2016.

- 28. Hawkey J, Hamidian M, Wick RR, et al. ISMapper: identifying transposase insertion sites in bacterial genomes from short read sequence data. BMC Genomics 2015; 16:667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lucidarme J, Hill DM, Bratcher HB, et al. Genomic resolution of an aggressive, widespread, diverse and expanding meningococcal serogroup B, C and W lineage. J Infect 2015; 71:544–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faur YC, Wilson ME, May PS. Isolation of N. meningitidis from patients in a gonorrhea screen program: a four-year survey in New York City. Am J Public Health 1981; 71:53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bartley SN, Tzeng YL, Heel K, et al. Attachment and invasion of Neisseria meningitidis to host cells is related to surface hydrophobicity, bacterial cell size and capsule. PLoS One 2013; 8:e55798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taha MK, Claus H, Lappann M, et al. Evolutionary events associated with an outbreak of meningococcal disease in men who have sex with men. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0154047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asbel L, Anschuetz G, Johnson C. Descriptive analysis of patients with N. meningitidis vs. N. gonorrhoeae urethritis [abstract THP 109]. In: Program and abstracts of the 2016 Annual STD Prevention Conference (Atlanta, Georgia: ). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Toh E, Gangaiah D, Batteiger BE, et al. Neisseria meningitidis ST11 complex isolates associated with nongonococcal urethritis, Indiana, USA, 2015–2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:336–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rice CE, Maierhofer C, Fields KS, Ervin M, Lanza ST, Turner AN. Beyond anal sex: sexual practices of men who have sex with men and associations with HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. J Sex Med 2016; 13:374–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kamiya H, MacNeil J, Blain A, et al. Meningococcal disease among men who have sex with men—United States, January 2012–June 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:1256–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nanduri S, Foo C, Ngo V, et al. Outbreak of serogroup C meningococcal disease primarily affecting men who have sex with men—Southern California, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:939–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Getman D, Jiang A, O’Donnell M, Cohen S. Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence, coinfection, and macrolide antibiotic resistance frequency in a multicenter clinical study cohort in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:2278–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hook EW, III, Handsfield HH. Gonococcal infections in the adult. In: KK, Holmes PF, Sparling WE, Stamm, ed. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 4th ed New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008: 627–645. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medini D, Stella M, Wassil J. MATS: global coverage estimates for 4CMenB, a novel multicomponent meningococcal B vaccine. Vaccine 2015; 33:2629–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.