Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction are chronic inflammatory conditions with overlapping pathophysiology and symptomatology. Both microbial infection and seborrhea contribute to the pathophysiology and both may benefit from treatment with tea tree oil (TTO). We evaluated the therapeutic effect of eyelids scrubbing with TTO in a group of patients with lid margin disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Forty patients were recruited. Half of them received lid scrubbing with a TTO formula (Naviblef™) and the other half was treated by massage and cleansing. The effect on ocular surface symptoms, tear film stability, and lid signs was evaluated.

RESULTS:

All patients receiving TTO improved in symptoms, signs, and tear film stability, and the improvement was statistically significant at P < 0.001. Only five patients in massage group showed improvement. The changes in massage group were not statistically significant at P < 0.001. TTO is very effective in relieving symptoms and improving tear film stability and lid signs.

Keywords: Blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction, ocular surface disease index, tea tree oil

Introduction

Blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) are chronic inflammatory conditions that involve the eyelid margins and meibomian glands, respectively. They have a complex pathogenesis and may result in alteration of the tear film, eye irritation, and ocular surface disease.[1] Their pathophysiology shows considerable overlap, with microbial infection and seborrhea playing the major role in the development of the surface disease.[2]

The clinical picture is also overlapping with no pathognomonic symptom or sign. Tea tree oil (TTO) has anti-infective and wound-healing properties and has proven effective in treating MGD associated with Demodex.[3]

In this study, we evaluated the therapeutic effects of eyelids scrubbing with TTO in a group of patients with lid margin disease (blepharitis/MGD).

Materials and Methods

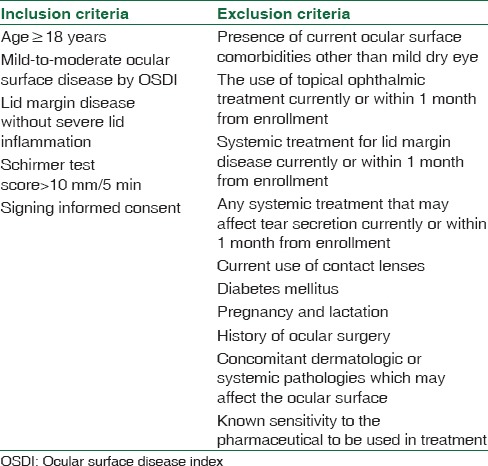

This study was conducted in compliance with good clinical practices, applicable local regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Forty patients with blepharitis/MGD were recruited between October 2015 and June 2016. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. The diagnosis was based largely on the recommendation of the International Workshop on MGD.[4]

Table 1.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were equally divided into two groups: TTO group and massage and cleansing group, which will be referred to as massage group. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. At enrolment, patients completed a self-evaluation questionnaire on ocular surface disease and the ocular surface disease index (OSDI) was calculated for each patient. A baseline slit lamp examination included examining the eyelids for margin hyperemia, presence of collarettes, presence of greasy scales or debris on eyelashes, and eyelash loss or misdirection. We also assessed the meibomian gland orifices and foam collection in the tear meniscus and at the lateral canthus. The ocular surface was assessed for the presence of greasy tear film, conjunctival hyperemia, and conjunctival and corneal staining. Schirmer 1 test with anesthesia scores was calculated for two eyes of each patient. Tear break-up time (TBUT) of the worse eye at baseline was considered for evaluating the effect of treatment on tear film stability. Using fluorescein dye, an illuminated slit lamp, and cobalt blue filter, the time needed till the first appearance of a dark, dry spot after a complete blink was measured. TBUT was checked twice in each eye and the two readings were averaged.

In TTO group, each patient was examined four times: at enrolment, then after 30, 45, and 60 days from beginning the treatment, while in massage group, they were examined at enrolment and after 30 and 60 days from initiating the treatment. At each follow-up visit, they were reevaluated for symptoms and lid signs. In the last checkup (60 days after starting treatment), OSDI and TBUT were also evaluated.

Patients in TTO group were prescribed a commercially available TTO eyelid scrub (Naviblef™ Eyelid Foam/Novax Pharma/Italy) to be applied 2 times daily in the 1st month (30 days).

The method of application was explained to the patients. The foam was to be sprayed on clean fingers; then, while eyes were kept closed, eyelashes and eyelid margins were to be rubbed with the foam for 60–90 s. After each application, eyes and eyelids were to be rinsed thoroughly with clean water. The frequency was reduced after the first follow-up visit to 1 time daily and was further reduced to 1 time every other day after 45 days of starting treatment. A preservative-free lubricant was prescribed 4 times daily after the scrub.

In the massage group, patients were advised about using warm compresses and performing eyelid massage for 5 min 4 times daily, in addition to cleansing the lid margins with mild (baby) shampoo and cotton buds 4 times per day, followed by preservative-free lubricants 4 times daily.

Primary outcome measures were a decrease in OSDI from baseline and an increase in TBUT. The secondary outcome measure was improvement in lid signs.

Results

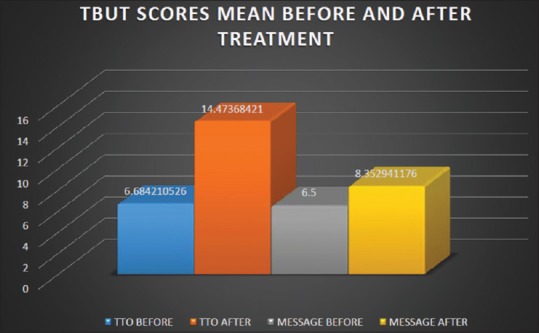

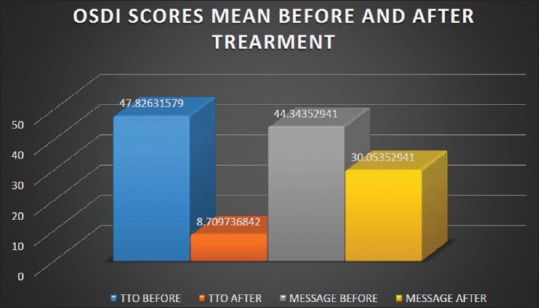

To determine the statistical significance of the improvement in OSDI and TBUT scores, the paired t-test with a two-tailed distribution was performed. A level of P = 0.01 was assumed significant to compare the results of both TTO group and the massage group before and after treatment. Excel 2016 was used to draw [Figures 1 and 2] and to perform all the mean and standard deviation calculations used to express the OSDI, TBUT, and age records and to perform the statistical analysis.

Figure 1.

Tear break-up time scores before and after treatment

Figure 2.

Ocular surface disease index scores mean before and after treatment

Eleven men and nine women were enrolled in TTO group. Their ages ranged between 39 and 68 years. Mean age was 51.47 ± 9.24 years. Nineteen of them completed the study; one female patient dropped out after developing contact dermatitis.

At baseline, in the TTO group, the mean of OSDI score was 47.83 ± 8.37, with 95% confidence interval ranging between 43.82 and 51.83. TBUT ranged between 5 and 8 s with a mean of 6.68 ± 0.84 s and a 95% confidence interval of 6.28–7.08. Posttreatment OSDI scored a mean of 8.71 ± 3.99 and the 95% confidence interval was 6.8–10.62. The TBUT improved to 14.47 ± 1.78 s ranging from 11 to 18 s with 95% confidence interval of 13.62–15.32. The change from baseline was statistically significant for both outcome measures at P < 0.001, and the conversion rate was 100%.

By the end of the study, all patients in TTO group reported subjective improvement in their symptoms notably light sensitivity, grittiness, soreness, discomfort during reading or night driving, and while using visual display units. One female patient complained of eye irritation and was found not to follow the instructions carefully as she kept her eyes open while massaging the lids. She was re-instructed regarding proper application and showed good improvement after that. Another female patient developed contact dermatitis in the upper eyelid as she scrubbed the entire area of the lid and not strictly the eyelid margin, and for that, she was excluded from the study. All patients were able to reduce the frequency of lubrication after 1 month.

In the massage group, there were 10 females and 10 males. Their age ranged between 43 and 70 years with a mean of 52.94 ± 9.31 years. Three male patients dropped out due to poor compliance.

Baseline OSDI mean was 44.34 ± 6.83 with 95% confidence interval of 40.88–47.80. Baseline TBUT ranged between 5 and 8 s with a mean of 6.5 ± 0.92 and 95% confidence interval of 6.04–6.96. After treatment, the mean for OSDI became 30.05 ± 8.86 with a 95% confidence interval of 25.56–34.53. TBUT ranged between 5.5 and 14 s with a mean of 8.35 ± 2.94 and the 95% confidence interval was 6.86–9.84. The changes in OSDI and TBUT were not statistically significant at P < 0.01 (P = 0.03, P = 0.01, respectively). The conversion rate was 29.4%. Only five patients improved subjectively. Improvement was mostly noticed in grittiness, soreness, and while watching TV, although they mentioned that commitment to treatment was not easy for them. None of the patients in this group including those who improved was comfortable reducing the frequency of lubrication. Figures 1 and 2 represent the pre- and post-treatment TBUT and OSDI scores for the two groups, respectively.

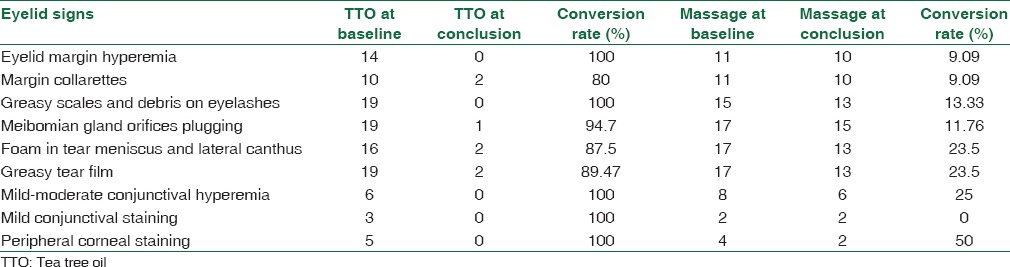

Data about lid signs in both groups at baseline and at conclusion of the study are shown in Table 2. Only signs that were positive in the study patients at inclusion are included.

Table 2.

Eyelid signs at baseline and at conclusion of study for tea tree oil and massage groups

Discussion

Lid margin disease is multifactorial. Both commensals and infective bacteria or the toxins produced by them may contribute to the pathologic course of blepharitis/MGD. The bacterial components may include Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Propionibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium sp., and Moraxella.[5,6] Infestation of the bases of eyelashes and follicles with Demodex mites can also cause blepharitis.[7,8,9,10] Demodex mites have been found in young adults, but the incidence of infestation increases with age.[11]

De Venecia and Siong found Demodex in patients with MGD, anterior blepharitis, and mixed blepharitis in an incidence of 85%, 95%, and 97%, respectively.[12] Symbiosis or commensalism between mites and microbes could be part of the pathogenesis of MGD. Obstruction of the meibomian glands by plugging solidified secretion also plays an important role in MGD development.[13] It is well agreed that it is the interrelation of many factors which results in inflammation of eyelids, and in real-life scenarios, bacteria usually exist in complex communities interacting with other organisms and rarely exist on their own.[14]

Because of this interaction and due to the considerable overlap in the pathophysiology and the clinical picture, effective management of lid margin disease should address the multiple underlying factors to positively reflect on patients' quality of life. Yet, there is little evidence in supporting a curative or universal approach to blepharitis management.[15] Treatment is generally based on severity, suspected etiology, availability of therapeutics, as well as the local clinical practices.

TTO is a natural oil distilled from the leaf of Melaleuca alternifolia that has antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and antiprotozoal properties in addition to an anti-inflammatory effect. It is effective against S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans and is known to be highly effective in eradicating Demodex.[7,16]

The formula of TTO that was used in our study contains extracts of TTO, extracts of pharmaceutical grade chamomile which has soothing and decongestant properties, and Vitamin B5 which is known to have moisturizing properties.

In this study, patients who used TTO enjoyed the positive effect shortly after starting the treatment with a significant improvement in OSDI and TBUT in all of them. The compliance was very good because of the rapid and noticeable change in symptoms that they felt. Typically, patients described having fresh eyes upon awakening in the morning. The need to use eye lubricants was greatly reduced after 1 month of daily application of the scrub. No antibiotic or steroid eye ointment was required to control symptoms or improve lid signs. In this, we agree with Hirsch-Hoffmann et al., who reported symptomatic improvement in 40.5% of their patients who used Naviblef®. Among the six different systemic and topical modalities of treatment they used, Naviblef® was the most effective in improving symptoms; this occurred despite a very low Demodex eradication rate (6%).[17] Koo et al. also found TTO eyelid scrub effective in improving subjective ocular symptoms in patients with Demodex blepharitis.[18] Our results also agree with those of Gao et al., who described symptomatic relief and notable reduction of inflammatory signs in 10 out of 11 patients they treated with TTO scrub and shampoo.[19] In our study, the female patient who developed contact dermatitis after applying the foam over the entire upper lid reaching the eyebrows was concomitantly using different kinds of cosmetic lotions which may have contributed to the development of irritation. Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in about 5% of those who use TTO.[20] This is however infrequent when it is used in a low concentration.

In the massage group, the mean difference in OSDI was very low, indicating that the number of patients who improved was low. Most patients confirmed that they performed the massage and cleansing at least once daily, but adherence to the instructions regarding the frequency, techniques, and duration of the massage session was greatly variable because they found it tedious and time-consuming. This may explain the poor benefit from treatment and the poor compliance. The report of the subcommittee of the International Workshop on MGD noted that although recommendations for the performance of lid warming and lid hygiene are commonly made, warm compress therapy is poorly standardized, the precise technique varies greatly both in duration and in frequency of lid warming and cleansing, and patients commonly develop their own methods of performing lid hygiene regardless of instructions.[1]

TTO scrub strips the lid margin from the irritating meibum and thus opens the plugged meibomian glands without the need for meibum expression, which is usually felt unpleasant by the patient. It also acts against a wide range of microorganisms that may possibly be present. The broad-spectrum therapeutic effect of TTO makes it an ideal and practical option to treat lid margin disease, especially when facilities to diagnose the underlying cause are unavailable. The wound-healing and soothing effects attributed to it and the rapid response adds to its affectivity in relieving symptoms and makes patients better at complying with treatment.

Conclusion

Further studies that include a large number of patients over prolonged time are important to define the role and the best practice in using TTO in ocular surface disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ, Glasgow BJ, Dogru M, Tsubota K, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1922–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seal DV, Wright P, Ficker L, Hagan K, Troski M, Menday P, et al. Placebo controlled trial of fusidic acid gel and oxytetracycline for recurrent blepharitis and rosacea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:42–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thode AR, Latkany RA. Current and emerging therapeutic strategies for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) Drugs. 2015;75:1177–85. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson A, Bron AJ, Korb DR, Amano S, Paugh JR, Pearce EI, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2006–49. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driver PJ, Lemp MA. Meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40:343–67. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien TP. The role of bacteria in blepharitis. Ocul Surf. 2009;7:S21–2. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, Liu DT, Baradaran-Rafii A, Elizondo A, et al. High prevalence of Demodex in eyelashes with cylindrical dandruff. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3089–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Chun YS, Kim JC. Clinical and immunological responses in ocular demodecosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1231–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JT, Lee SH, Chun YS, Kim JC. Tear cytokines and chemokines in patients with Demodex blepharitis. Cytokine. 2011;53:94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Chun YS, Kim JH, Kim ES, Kim JC. The relationship between Demodex and ocular discomfort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2906–11. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Sheha H, Tseng SC. Pathogenic role of Demodex mites in blepharitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:505–10. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833df9f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Venecia AB, Siong RL. Demodex sp. infestation in anterior blepharitis, meibomian-gland dysfunction, and mixed blepharitis. Phillip J Ophthalmol. 2001;36:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinna A, Piccinini P, Carta F. Effect of oral linoleic and gamma-linolenic acid on meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2007;26:260–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318033d79b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zinder SH, Salyers AA. Microbial ecology-new directions, new importance. In: Boone DR, Castenholz RW, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Biology. Vol. 1. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001. pp. 101–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD005556. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005556.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carson CF, Hammer KA, Riley TV. Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea tree) oil: A review of antimicrobial and other medicinal properties. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:50–62. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.50-62.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch-Hoffmann S, Kaufmann C, Bänninger PB, Thiel MA. Treatment options for Demodex blepharitis: Patient choice and efficacy. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2015;232:384–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koo H, Kim TH, Kim KW, Wee SW, Chun YS, Kim JC, et al. Ocular surface discomfort and Demodex: Effect of tea tree oil eyelid scrub in Demodex blepharitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1574–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.12.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Elizondo A, Tseng SC. Clinical treatment of ocular demodecosis by lid scrub with tea tree oil. Cornea. 2007;26:136–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000244870.62384.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Studdiford J, Stonehouse A. Allergic Contact Dermatitis from Tea Tree Oil (Melaleuca alternifolia) National Institutes of Health, Department of Family & Community. Medicine. Faculty Papers. Paper 12. 2007. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 16]. Available from: http://www.jdc.jefferson.edu/fmfp/12 .