Abstract

Introduction:

Symptoms of depression vary between the males and females. Depressed men show behaviors such as irritability, restlessness, difficulty in concentrating, and instead of the usual behaviors. Sleep disturbance is a common symptom in depressed men. Men are less likely to go to doctors and unconsciously show other behaviors such as anger instead of the sadness. It seems that considering depression as “feminine” is a great injustice toward male patients whom their illness will not be diagnosed nor treated.

Materials and Methods:

The sample consisted of 191 depressed adolescents, 108 males and 83 females aged 13–19 years old. Data collected for 10 years from 2005 to 2015 and their depressive symptoms were evaluated by the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition.

Results:

Depressed girls felt sadness, guilt, punishment, worthlessness, low energy and fatigue, or more asthenia, whereas depressed boys have symptoms such as irritability, depression, suicidal thoughts, or desires to reduce their pleasure. The results of t-test showed that the difference between the total scores of boys and girls with depressive disorder (16.93) is significant at 0.001. F values for feeling sad (58.13), hatred of self (12.38), suicidal thoughts or desires (12.97), restlessness (17.35), and irritability (46. 41) were significant in the 0.001.

Conclusion:

Experiencing depression in boys and girls according to the role of gender was different. Gender can have an effective role in showing depression symptoms in adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescence, Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition, depression, gender differences, symptoms

Introduction

In early adolescence, the onset of depression has a steady climb. At the age of 6–11, the incidence of depression is 2%–3% and at the age of 11–15 with a relative increase is 3%–8%. Moreover, by the age 13–15 years, these symptoms will be twice in girls than boys and will continue until the end of adolescence.[1] The previous researches have shown that the prevalence of depression in women is twice than men,[2] and the first differences in depressive symptoms are revealed between the ages of 12 and 14.[3,4,5,6] The reasons for gender differences in depression are still not fully understood. However, cognitive theories have shown that adolescent girls and young women are more capable of showing cognitive style with negative assessment of themselves and rumination. This may help creating a background for depression.[4,5,6]

Gender-based differences in cognitive symptoms in patients with depression and healthy individuals have been confirmed. For example, women generally earn higher scores than men in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).[7] These gender differences are also have been seen even in women's brain function with a history of depression since childhood by showing changes of alpha waves in the right forehead.[8] Studies that compare individual symptoms of depressive symptoms in depressed men and women have shown that depressed women have more physical symptoms such as changes in appetite, loss or weight gain, change in sleep patterns, psychomotor slowing, psychosomatic symptoms, crying, guilt, and depression than depressed men.[9,10,11] However, depressed men are more concern about their health and show depressive symptoms as irritability.[12] However, gender differences in depressive symptoms among children and adolescents on the basis of major depression standards or dysthymia disorder has not been found.[12,13,14] Perhaps, the limitations of previous studies, such as the limited number of samples could affect the result of this research. Since all of them have reported differences in body image, loss of appetite and weight in girls and withdrawal and isolation, insomnia, and inability to work in boys.[15]

The researchers found that a third of men and women are in the criteria for diagnosing depression. Depression symptoms in men and women are not similar to each other. Men may be reluctant to reveal depression symptoms. Depression symptoms in men are anger, suicide, distraction, and irritability rather than sadness. The results of study on 3310 women and 2382 men showed that about 26% of men and 22% of women had depression criteria. The researchers suggested diagnosing depression in men and women; it is better to find a new standard to replace the previous criteria. In addition to reducing and quality of life, depression in men has other signs such as smoking, alcohol consumption, inactivity and sleep problems. We must accept that depression is not a feminine disease. Lack of daily activities, exercise and changes in sexual behavior in men is the most important indicators of depression in men.[16]

Materials and Methods

The current study is cross-sectional, and the data were collected repeatedly using BDI from 2005 to 2015. The samples (adolescents diagnosed with depression) were evaluated by neurologists and psychiatrists in Shafa psychiatric center in Rasht (a city north of Iran) during 10 years by BDI. In this study, patients who had other disorders (such as serious physical or mental disease, abnormal intelligence, behavioral disorders, and addiction) in addition to depression were excluded. All the patients in this study were residents of urban or rural areas in Gilan so they can be easily reached. The final sample consisted of 191 adolescents (83 females and 106 males) between the ages of 13 and 19 years with an average age of 15.82 and a standard deviation of 1.63. According to experts’ diagnosis, 54 people had major depressive disorder and 137 people had dysthymia and minor depression.

Measurement tool

BDI is one of the most appropriate methods to reflect depressive states. BDI has 21 articles which evaluate three dimensions of depression: Physical symptoms, cognitive symptoms, and behavioral symptoms. Each article has four options scored on 0–3 and determines degrees of depression from mild to severe. The maximum score on the test is 63, and the minimum is 0. Comparing BDI Hamilton Depression Rating Scale with showed that BDI is not depends on the peoples’ skill and is more concerned with assessing psychological characteristics rather than physical and physiological discomfort. The correlation between these two questionnaires is 0.75. This questionnaire has been studied by many people over the years and is known as the best questionnaires to assess depression.[17,18] BDI-Second Edition (BDI-II) is the revised form of BDI to measure the severity of depression.[19] This questionnaire is more consistent with DSM-IV and is can be used in the population of 13 years and over. Twenty-one article of the questionnaire is classified in three groups: Affective symptoms, cognitive symptoms, and physical symptoms.[17] Demographic characteristics, age, education, location, and social class were studied using t-test and MANOVA.

Results

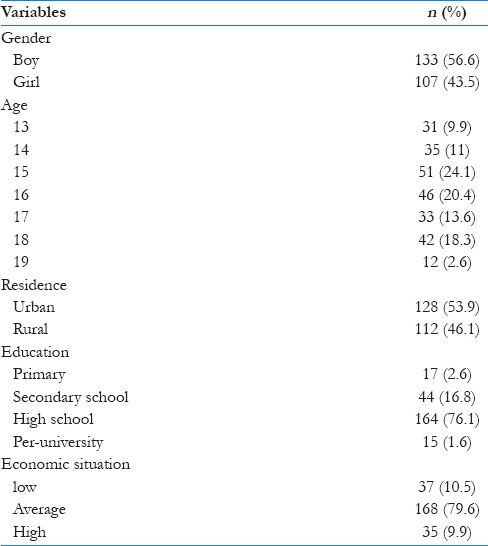

The sample group included 191 patients aged 13–19 years with a mean age of 15.82 and a standard deviation of 1.63. One hundred and six males and 83 females were in this study. Nineteen patients (9.9%) were 13 years, 21 patients (11%) were 14 years, 46 patients (24.1%) were 15 years, 39 patients (20.4%) were 16 years, 26 patients (13.6%) were 17 years, 35 patients (18.3%) were 18 years, and five patients (2.6%) were 19 years old. Based on location, 103 patients (53.9%) living in the city and 88 patients (46.1%) lived in rural areas. According to education, five patients (2.6%) were in primary school, 32 patients (16.8%) were in high school JR, 151 (76.1%) high school, and three patients (1.6%) had university education. In terms of the economic situation, the sample was divided into three groups based on family income, parents’ education and occupation. According to the sample group, twenty patients (10.5%) were in the lower class, 152 (79.6%) were average, and 19 patients (9.9%) were high [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

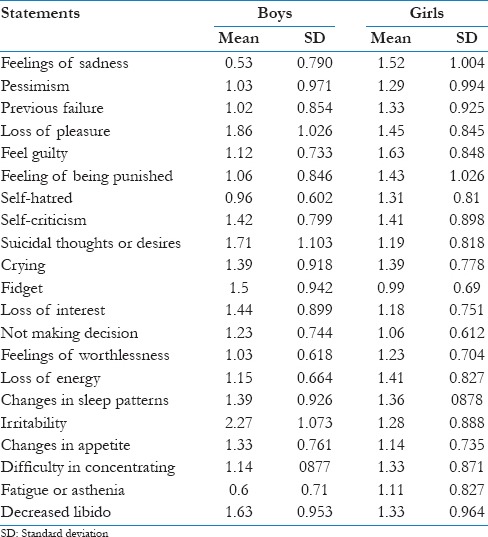

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of the statements of depression in girls and boys. In BDI-II, average depression symptoms for boys was between 2.27 and 0.53 (the lowest score belonged to feelings of sadness or lethargic, and the highest score belonged to irritability, suicidal thoughts or desires, and reducing pleasure) and for girls was between 1.52 and 0.99 (the lowest score belonged to feelings of sadness, guilt, feeling punished, feelings of worthlessness, decreased energy, and fatigue or weakness).

Table 2.

The mean and standard deviation for statements of depression, separated for boys and girls

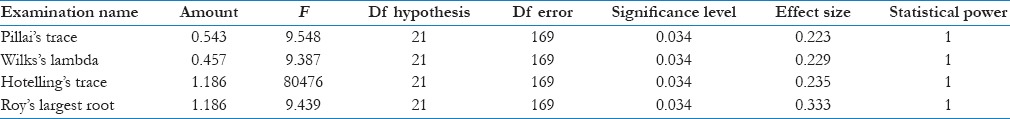

T-test was used to compare the two means. The comparison between independent groups showed that score difference in both groups was significant in 0.001. Multivariate analysis of variance was used to verify that the two groups differ on which of the components of depression. The results are given in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Results of multivariate analysis of variance test for depression variable and its component between the groups

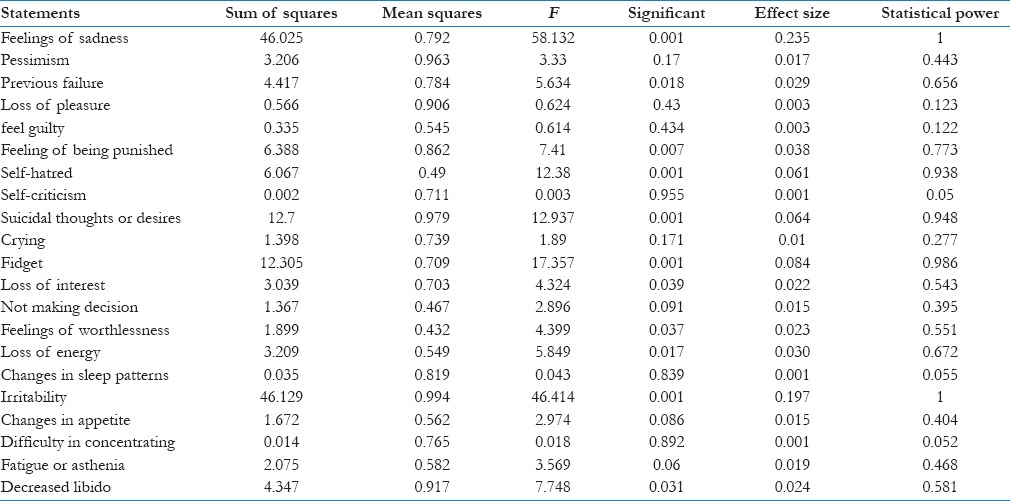

Table 4.

The results of multivariate analysis of variance analysis on average depression and its components in two groups of boys and girls with a depressive disorder

Based on the results presented in Table 3, the effect of group on the linear combination of dependent variables is significant (P < 0.05 and F = 9.548, Pillai's Trace = 0.543, and Wilks's Lambda = 0.457). In other words, between two groups of depressed girls and boys, at least in one of the depression components there is a significant difference.

According to Table 4, F for the following components is as follows: feeling sad (58.132), hatred of self (12.38), suicidal thoughts or desires (12.973), restlessness (17.357), and irritability (46.414) which were significant at 0.001. F for the following components is as follows: pessimism (3.33), previous failure (5.63), decreased pleasure (0.624), guilt (0.614), feeling punished (7.41), self-criticism (0.003), crying (1.89), loss of interest (4.324), lack of decision (2.893), feelings of worthlessness (4.399), reduction of energy (5.849), changes in sleep patterns (0.043), change in appetite (2.974), difficulty concentrating (0.018), fatigue or asthenia (3.569), and decreased libido (4.738). These results indicate that there is no significant difference in these components in these two.

Discussion

The previous studies on the prevalence of depression showed that the severity of symptoms in girls is higher than boys. However, research has shown that depression severity in both genders is equal and the fundamental differences are in depression symptoms.[12,13] Recent research findings showed that feeling of guilt and dissatisfaction in girls is higher than boys. The results obtained in this study were inconsistent with the results of studies performed by Wade et al. 2002 and Hankin. Research carried out about ranking depressive symptoms in both boys and girls showed that depressed girls showed symptoms such as sadness, depressed mood, hopelessness, self-blame, feelings of failure, difficulty in concentrating, fatigue, and concerns in BDI on physical health. In this study, anhedonia has the highest rate in depressive symptoms. Hence, the results can be interpreted as follows: when adolescents say that there is nothing attractive in life and they do not enjoy, these symptoms can be alarming because it is a sign of starting depression. While boys with depression showed symptoms like such as anhedonia, difficulty sleeping morning tiredness. Our findings were inconsistent with the results of studies performed by Sorensen 2005. Messi 2001 (using logistic regression) showed that anhedonia in boys (in BDI) could be referred as a strong predictor of depression. Gender differences in feelings of guilt are fairly considered throughout diagnosing depression so that Breslau and Davis 1985 stated that in their research feeling guilty is a significant predictor of depressive symptoms in women. Furthermore, in this study, feeling guilty has a significant percentage of in girls.

Feeling guilty is one of the signs of depression that can be noticed in research. Girls at an early age and lower social class are more likely to have feeling guilty.[20] Change in appetite[19,20,21] is referred as the main symptom of depression. Their studies had shown that the purpose of these changes in appetite (loss of appetite in girls and increasing appetite in boys) were to inhibit or reduce stress, but in this study, there was no significant relationship between changes in appetite and depressive symptoms in boys and not girls.

One of the most important gender differences in depression is difficulty in concentrating. Difficulty in concentrating is one of the important signs of depression in women. Difficulty in concentrating like rumination is more common among women than men, which is consistent with the results of the current study.[22,23,24,25,26]

Loss of pleasure, changes in sleep patterns, irritability, and fatigue were the experiences of depressed boys, and for the first time, it was observed that depressed men may reach to higher levels in these symptoms.[27] This issue has been in accordance with the results of our survey (high fatigue among boys at least indicates part of gender differences because of the absence of pleasure). Finally, recent findings showed the importance of gender differences for some of the symptoms of depression, such as feelings of sadness, self-hatred, suicidal thoughts and desires, restlessness, and irritability in BDI symptoms. For other symptoms such as sleep problems (usually mentioned by parents of adolescents frequently) in this study, no difference was noted. As a result, the abovementioned results were different from the results of studies in Europe and North America.[28]

In summary, the evidence for gender differences among a sample of depressed adolescents showed that depressed girls are more likely to show cognitive and physical symptoms of depression than depressed boys. Knowing this potential difference may be helpful for doctors in treatment. For example, if feeling guilty and dissatisfaction with body image of girls are higher than boys, cognitive interventions to eliminate excessive guilt and self-hatred will be effective.[29] Goodwin and Gotlib 2004 studies showed that gender differences in dealing with stress styles significantly increase the risk of major depression.[30] Neuroticism characteristics may have significant role in increasing the risk of depression in girls. Age 13 could be the beginning of depression that requires special attention of the WHO.[31]

Conclusion

The results showed that the experience of guilt and dissatisfaction with body image in depressed girls is higher than boys. Symptoms of depression in girls include having sadness, depressed mood, hopelessness, self-blame, feelings of failure, difficulty in concentrating, fatigue, and concerns about health, whereas in boys, the symptoms are lack of fun, trouble in sleeping, fatigue, and lack of enjoyment of life. Feeling guilty can be mentioned as a strong predictor of depression in girls. Depressed boys experienced loss of pleasure, changes in sleep patterns, irritability and fatigue, and possibly increase of fatigue among boys is a symptom of anhedonia. The findings confirm the role of gender in depression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chaplin TM, Gillham JE, Seligman ME. Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms: A Longitudinal study of early adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2009;29:307–27. doi: 10.1177/0272431608320125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the children's depression inventory: A meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:578–88. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wade TJ, Cairney J, Pevalin DJ. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:190–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garber J, Martin NC. Negative cognitions in offspring of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk. In: Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, editors. Children of Depressed Parents: Mechanisms of Risk and Implications for Treatment. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 121–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:773–96. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller A, Fox NA, Cohn JF, Forbes EE, Sherrill JT, Kovacs M. Regional patterns of brain activity in adults with a history of childhood-onset depression: Gender differences and clinical variability. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:934–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter JD, Joyce PR, Mulder RT, Luty SE, McKenzie J. Gender differences in the presentation of depressed outpatients: A comparison of descriptive variables. J Affect Disord. 2000;61:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein B. Gender differences in the prevalence of somatic versus pure depression: A replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1051–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Yonkers KA, McCullough JP, Keitner GI, et al. Gender differences in chronic major and double depression. J Affect Disord. 2000;60:1–1. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacs M. Gender and the course of major depressive disorder through adolescence in clinically referred youngsters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1079–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sørensen MJ, Nissen JB, Mors O, Thomsen PH. Age and gender differences in depressive symptomatology and comorbidity: An incident sample of psychiatrically admitted children. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masi G, Favilla L, Mucci M, Poli P, Romano R. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with dysthymic disorder. Psychopathology. 2001;34:29–35. doi: 10.1159/000049277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron P, Joly E. Sex differences in the expression of depression in adolescents. Sex Roles. 1988;18:7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seaman AM. Percent of depression men comparable to women. [Last cited on 2013 Aug 28];JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 102:966–9. Avaliable from: http://www.reuters.com/JAMA Psychiatry/Aug.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajabi Gh R, Kasmai SK. Psychometric properties of a Persian language version of the beck depression inventory. BD-I-II-persian. (second edition) 2013;3:139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a Persian-Language version of the Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:185–92. doi: 10.1002/da.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox KR, Page A, Armstrong N, Kirby B. Dietary restraint and self-perceptions in early adolescence. Pers Individ Differ. 1994;17:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whisman MA, Perez JE, Ramel W. Factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) in a student sample. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:545–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<545::aid-jclp7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson TJ, Stegge H, Miller ER, Olsen ME. Guilt, shame, and symptoms in children. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:347–57. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotenberg KJ, Flood D. Loneliness, dysphoria, dietary restraint, and eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:55–64. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199901)25:1<55::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslau N, Davis GC. Refining DSM-III criteria in major depression. An assessment of the descriptive validity of criterion symptoms. J Affect Disord. 1985;9:199–206. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:259–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Zehm K. Dysphoric rumination impairs concentration on academic tasks. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27:309–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sund AM, Larsson B, Wichstrom L. Depressive symptoms among young Norwegian adolescents as measured by the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:222–9. doi: 10.1007/s007870170011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seiffge-Krenke I, Stemmler M. Factors contributing to gender differences in depressive symptoms: A test of three developmental models. J Youth Adolesc. 2002;31:405–17. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vredenburg K, Krames L, Flett GL. Sex differences in the clinical expression of depression. Sex Roles. 1986;14:37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayward C, Gotlib IH, Schraedley PK, Litt IF. Ethnic differences in the association between pubertal status and symptoms of depression in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:143–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin RD, Gotlib IH. Gender differences in depression: The role of personality factors. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strachan MD, Cash TF. Self-help for a negative body image: A comparison of components of a cognitive-behavioral program. Behav Ther. 2002;33:235–51. [Google Scholar]