Abstract

Wnt signaling plays essential roles in both embryonic pattern formation and postembryonic tissue homoestasis. High levels of Wnt activity repress foregut identity and facilitate hindgut fate through forming a gradient of Wnt signaling activity along the anterior-posterior axis. Here, we examined the mechanisms of Wnt signaling in hindgut development by differentiating human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into the hindgut progenitors. We observed severe morphological changes when Wnt signaling was blocked by using Wnt antagonist Dkk1. We performed deep-transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) and identified 240 Wnt-activated genes and 2023 Wnt-repressed genes, respectively. Clusters of Wnt targets showed enrichment in specific biological functions, such as “gastrointestinal or skeletal development” in the Wnt-activated targets and “neural or immune system development” in the Wnt-repressed targets. Moreover, we adopted a high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation and deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) approach to identify the genomic regions through which Wnt-activated transcription factor TCF7L2 regulated transcription. We identified 83 Wnt direct target candidates, including the hindgut marker CDX2 and the genes relevant to morphogenesis (MSX1, MSX2, LEF1, T, PDGFRB etc.) through combinatorial analysis of the RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data. Together, our study identified a series of direct and indirect Wnt targets in hindgut differentiation, and uncovered the diverse mechanisms of Wnt signaling in regulating multi-lineage differentiation.

Highlights: hESC, Wnt targets, hindgut specification, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, APLNR

1. Introduction

The gastrointestinal tract is assembled from the progenitors of the three germ layers during early embryogenesis, and the mechanism for the formation of primitive gut tube is conserved across all vertebrate species[1–3]. Critical events in early gut formation are the invagination of the definitive endoderm (DE) and subsequent growth and differentiation of the adjacent splanchnic mesoderm during and shortly after gastrulation. The ventrally directed invagination of endoderm gives rise to two ventral pockets of endoderm known as the anterior intestinal portal and the caudal intestinal portal. The invaginations migrate towards each other until the endoderm fuses at the midline to form tubes [4–6]. Meanwhile, the endoderm becomes broadly regionalized along the anterior-posterior axis [1]. The lateral plate-derived splanchnic mesoderm is recruited to the endoderm prior to the gut tube closure and forms the outer layer of the gut tube [7]. Although the events in the primitive gut tube formation are well described, the molecular mechanisms underlying the initial formation and early specification of the hindgut are poorly understood.

Coordinated differentiation of the splanchnic mesoderm and posterior endoderm is well orchestrated through several major signaling pathways, including Hh, Wnt, FGF, BMP and Retinoic Acid (RA) [1, 8, 9]. Hh-mediated signaling from the endoderm directs the developmental potential of the adjacent mesoderm [10, 11]. The directional migration of endoderm cells during gastrulation is controlled by mesoderm-dependent Wnt/PCP, VEGF-C and SDF1/CXCR4a signaling pathways [12–16]. Moreover, the mesoderm sends instructive signals (Wnt, FGF, RA and BMP) to the endoderm to establish regional identities, which are characterized by several transcription factors including SOX17, FOXA2, SOX2, HHEX and CDX2 [17–19].

Studies using a number of in vivo mouse embryo models revealed essential roles of Wnt signaling in vertebrate hindgut development. Wnt signaling acted directly on DE to initiate expression of the intestinal transcriptional factor Cdx2, which determined the intestinal anterior-posterior domain specification [20]. Several Wnt ligands, such as Wnt2b, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, Wnt8a and Wnt11, are expressed in the posterior domains of the embryo [21]. At E8.5, an overlapping expression of Tcf7l2 and Tcf7l1 was detected in the hindgut. Simultaneous deletion of both genes led to anomalies of caudal embryo, including severe developmental defects in the hindgut region and duplications of the neural tube [22]. Furthermore, previous evidence also demonstrated that ablation of β-catenin specifically in the primitive node, notochord, and anterior primitive streak of the mouse embryo led to DE formation defects and ectopic precardiac mesoderm formation [23].

Previously, in order to identify Wnt targets in the intestinal cells, most studies made use of systems (such as colorectal cancer cell lines) in which β-catenin was constitutively activated [24–26]. The downstream effect of the Wnt signal is largely dependent on the tissue type and the cellular context [27–29]. Although Wnt signaling plays a predominant role in hindgut development, little is known about the identity of the Wnt targets during embryonic development. Here, we choose to address this issue by using an in vitro differentiation system in which the combined activities of Wnt and FGF signaling efficiently pattern DE into CDX2+ hindgut endoderm and promote the morphogenesis of a two-dimensional (2D) sheet of DE into three-dimensional (3D) structures, termed spheroids [9, 30]. The spheroid consists of an epithelial layer surrounded by a mesenchymal layer. We found the outer mesenchymal layers became thinner and the inner epithelial layers began to express the foregut marker SOX2 within the spheroids after inhibition of Wnt signaling. We extracted RNA from DE, DE cultured in media supplemented with FGF4+Wnt3a (FW), or FGF4+Dkk1 (FD) and subjected the three samples to RNA-seq analyses in an effort to characterize the genome-wide gene expression changes elicited by Wnt signaling. Hierarchical Clustering analysis and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) suggest that Wnt signaling participates in the hindgut specification through promoting the mesodermal or endodermal development and simultaneously inhibiting the neuroectodemal development. We also performed ChIP-seq experiments to identify the potential targets directly regulated via TCF7L2. In order to gain additional insights into the diverse mechanisms of Wnt signals, we investigated the molecular characteristics of one novel Wnt direct target APLNR. We detected that APLNR was expressed in both the mesendoderm-like cells and mesenchymal cells through RT-qPCR together with flow cytometry analysis. Our study provides important sources of data for investigating the mechanisms of how the mesenchymal and endodermal layer differentiation are coordinated by Wnt signaling during hindgut formation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1.Hindgut Endoderm Induction and Patterning

HESCs were maintained on Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in mTesR1 media (Stem Cell Technologies). DE Differentiation was carried out as previously described [30–32]. We passaged the cells as small clumps using dispase onto Matrigel-coated plates. Two to three days later, hESCs were grown to nearly 95% confluence. We treated the hESCs with activin A (100ng ml−1) (R&D Systems) and increasing concentrations of 0%, 0.2% and 2% defined fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) in RPMI1640 media for three consecutive days. We incubated the DE cells in RPMI1640 media plus 2% defined fetal bovine serum, 500ng ml−1 FGF4 (R&D Systems) and 500ng ml−1Wnt3a (R&D Systems) for 96 hours. Within two to four days, 3D floating spheroids delaminated from the adherent cultures.

2.2.Directed Differentiation into the Hindgut and Intestinal Organoids

We transferred the spheroids into a previously described in vitro system to support the intestinal growth and differentiation [33, 34]. The spheroids were embedded in the Matrigel (BD Bioscience; no.354234) containing 500 ng ml−1 R-Spondin1 (R&D Systems), 100 ng ml−1 Noggin (R&D Systems) and 50 ng ml−1 EGF (R&D Systems). After the Matrigel solidified, the medium (advanced DMEM/F12; Invitrogen) supplemented with L-glutamine, 10 µM HEPES, N2 supplement (Invitrogen), B27 supplement (Invitrogen) and penicillin/streptomycin was overlaid. The growth factor-containing media were replenished every 4 days.

2.3.Immunostaining and Microscopy

We performed antibody staining of the differentiated cells according to standard protocols. The following primary antibodies were used: Rabbit anti-CDX2 (Abcam), Mouse anti-CDX2 (BioGenex), Goat anti-SOX2 (Santa Cruz), Rabbit anti-E-Cadherin (Cell signaling), Rabbit anti-Vimentin (cell signaling), Rabbit anti-FoxF1 (abcam), Rabbit anti-PDGFRB (cell signaling), Rabbit anti-LEF1 (cell signaling), Rabbit anti-Hand1 (Novus Biologicals) and Mouse anti-APLNR (R&D Systems). We stained the nuclei by using Hoechst 33258 (Sigma). The primary antibodies were detected by fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies from Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories. We collected the images by using the Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope and processed the images with Adobe Illustrator.

2.4.Sample Preparation and RNA-seq

We isolated the three samples of DE, DE cultured in the media supplemented with FW, or FD. Total RNA was purified from the three cell samples with the Qiagen RNeasy kits. Paired-end sequencing was performed with the Illumina platform of Beijing Institute of Genomics.

2.5.ChIP-seq

We performed the ChIP experiment with the kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Three 6-well transwell plates of hindgut-like cell cultures derived from hESCs were sonicated for 2*30 cycles of 5 seconds on/off at the low power setting using the Diagenode’s Bioruptor Ultrasonicator. The majority of chromatin fragments were sheared between 300 and 500bp. We performed immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody against TCF7L2 (Cell signaling) or a polyclonal antibody against TCF7L2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), respectively. Each experiment was replicated twice and the data from all the candidate genes were pooled together. Input DNA was used as the sequencing control. ChIP-seq was performed with the Illumina platform of Beijing Institute of Genomics.

2.6.RT-qPCR Analysis

Reverse transcription was carried out with the GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. We performed qPCR by using GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) on the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system. The PCR primers sequences were typically obtained from qPrimerDepot (http://primerdepot.nci.nih.gov/).

2.7.Flow Cytometry Analysis

To detect and isolate the APLNR+ cells, we conjugated anti-human APLNR mAb (clone 72133, R&D Systems) with APC by using the Lightning-Link-APC kit (Innova Biosciences). The DE cells cultured in the media FW for 96 hours were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. We dissociated the cultures into single cells with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies) and labeled the single-cell suspensions with the following Abs: APC-conjugated anti-APLNR (R&D Systems), APC-conjugated anti-IgG (R&D Systems), PE (or APC)-conjugated anti-CXCR4 (BD Biosciences), PE (or APC)-conjugated anti-IgG (BD Biosciences), PE-cy7-conjugated anti-CD117 (eBioscience) and PE-cy7-conjugated anti-IgG (eBioscience). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on the MoFlo XDP Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

2.8.Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times and similar results were obtained. The data is presented as mean ± SD. Student’s t test was used to compare the effects of all treatments. Statistically significant differences are indicated as follows: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 and *** P<0.001.

2.9.Accession Numbers

The raw illumina sequencing data are available in the NCBI short read archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/sra.cgi) with accession number SRP072721. All the raw sequence data described in the manuscript are available under the BioProject PRJA317038. Illumina sequencing reads have been deposited at NCBI SRA database under the following accession numbers (96h_FD: SRR3318876; 96h_FW: SRR3318955; DE: SRR3319045; TCF7L2_monoclonal1: SRR3321272; TCF7L2_monoclonal2: SRR3321273; TCF7L2_polyclonal1: SRR3321274; TCF7L2_polyclonal2: SRR3321275; Input: SRR3321276). Hatzis’s microarray data of TCF7L2 targets in colorectal cancer cells were accessed at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/, experiment code E-TABM-402.

3. Results

3.1.Intestinal in vitro Differentiation System Mimics the Role of Wnt Signaling in Embryonic Hindgut Specification

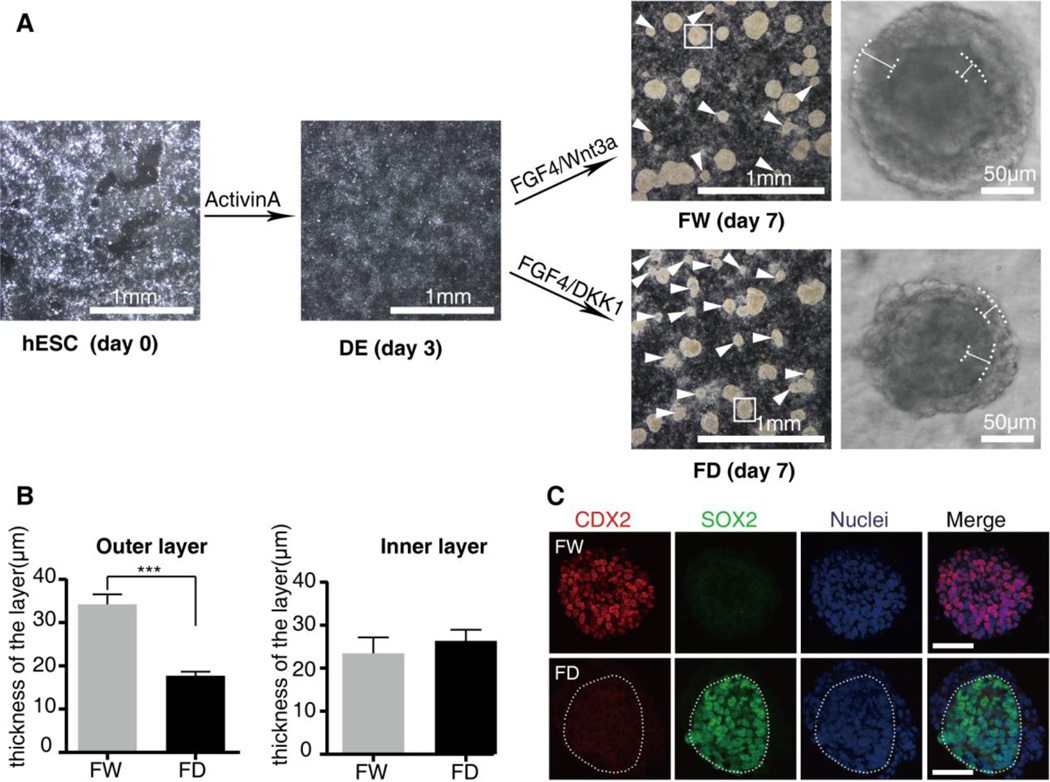

In the intestinal in vitro differentiation system previously established [35], recombinant ligand Wnt3a was added to the culture media to promote the hindgut morphogenesis and differentiation. Upon activation of Wnt signaling, the differentiated cells expressed the hindgut marker CDX2 and formed 3D spheroids [35]. To optimize the differentiation conditions, we investigated hESC seeding density as a source of variability in the differentiation process. We observed that fewer spheroids delaminated from the tissue culture dish at either a sparse or a dense seeding density (Figure S1 A–C′). Finally we chose growth of hESCs to 90–95% confluence in 2–3 days as the initial condition of differentiation. Z-stack confocal images showed that the outermost cells adjacent to the Vimentin+ mesenchymal layers of the spheroids coexpressed the hindgut endoderm markers CDX2 and SOX17, while the innermost layer did not express Sox17 (Figure S1 D–D′). To investigate the role of Wnt signaling in promoting the differentiation of hESC into hindgut-like cell cultures, we depleted Wnt signaling by replacing Wnt3a with Dkk1 which has been shown to act as an antagonist of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling [36]. We found more spheroids failed to delaminate and the average size of the spheroids became smaller after inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figure 1A). Under higher magnification, we also observed striking morphological changes not only in the size of the spheroids but also in the thickness of the outer mesenchymal layers (Figures 1A and 2A). Further quantification of the layer thickness revealed a significant decrease in the outer layer of the spheroids, and revealed no significant difference in the inner layer of the spheroids after inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figure 1B). This result suggested the role of Wnt signaling in promoting the mesoderm formation during the in vitro differentiation of hESCs into hindgut-like cell cultures.

Figure 1. Intestinal in vitro differentiation system mimics the role of Wnt signaling in embryonic hindgut specification.

(A) Bright-field images of hESC, DE, DE cultured for 96 hours in media supplemented with FW or FD. At day 7 of differentiation, much more spheroids (white arrows) failed to delaminate from the adherent cultures in the media supplemented with FD. The right panels are the magnified view of the delaminated spheroids. We observe dramatic morphological changes in the spheroids after inhibition of Wnt signaling. The outer layer and inner layer edges of the spheroids are lined out with white lines and the thickness is measured with the Axiovison4.0 analysis software (Carl Zeiss). Scale bar is shown on each image. (B) Quantification of the thicknesses in the outer layers and inner layers of the spheroids. The thickness of the outer layer is significantly reduced, whereas the thickness of the inner layer is not significantly changed after inhibition of Wnt signaling. Means ± SD are shown. N=20 spheroids, *** P < 0.001. (C) Immunostaining of the hindgut marker CDX2 and foregut marker SOX2 on the spheroids showed that the inner layer expressed Sox2 rather than CDX2 after inhibition of Wnt signaling. The dashed line highlights the inner epithelial layer. Scale bars, 50µm.

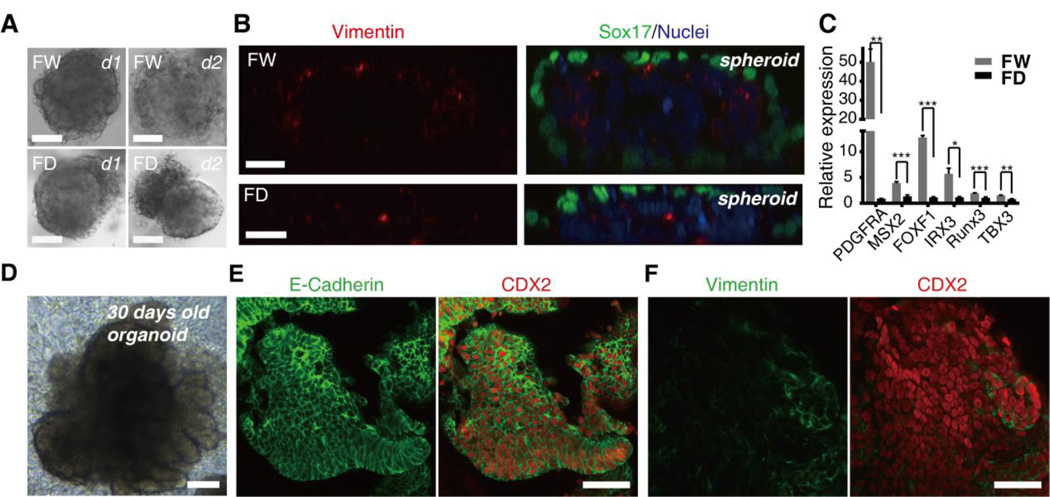

Figure 2. Transient inhibition of Wnt signaling blocked the growth of organoids.

(A) Bright-field images show that dramatic morphological changes occurred within 24 hours after the spheroids were seeded in the Matrigel. Scale bars, 50µm. (B) Representative Z-stacked images of spheroids immunostained for Vimentin (green), and SOX17 (red), counterstained with DAPI (blue, nuclei). The expression of Vimentin was significantly reduced after inhibition of Wnt signaling. Scale bars, 20µm. (C) RT-qPCR revealed a significant reduction in the expression of several other mesenchymal specific genes after inhibition of Wnt signaling. Means ± SD are shown. N=3~5 biological samples. * P < 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P < 0.001. (D) The Bright-field image of day 30 organoids shows that the organoids grew into finger-like protrusions within one month in the normal conditions. Scale bar, 100µm. (E-F) CDX2 (Red), E-Cadherin (green) and Vimentin (green) immunostaining demonstrated that virtually all of the cells in the organoids expressed the intestinal master transcription factor CDX2 and the epithelial marker E-Cadherin after 30 days in culture. In addition, a few Vimentin+ mesenchymal cells still existed in the periphery of the organoids. Scale bars, 50µm.

In order to assess how the endoderm patterning process was affected by Wnt signaling in the in vitro differentiation system, we examined the expression of the anterior and posterior gut endoderm markers SOX2 and CDX2. Consistent with previous findings [35], the spheroids consisted of CDX2+ cells in the presence of Wnt3a (Figures 1C and S1 D–D′). After inhibition of Wnt signaling, the epithelial layer of the spheroids uniformly expressed the foregut marker SOX2 (Figure 1C). In addition, we also observed SOX2+ cells instead of CDX2+ cells in the 3D tubes after inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figures S2C–C‴ and S2D–D‴). Interestingly, none of the monolayer cells expressed the hindgut marker CDX2 or the foregut marker SOX2 after inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figures S2A–A‴ and S2B–B‴). We inferred that the epithelial cells within the inner layer of both the 3D tubes and the spheroids still possessed plasticity to differentiate into foregut. Collectively, this data argues that Wnt signaling participates in the hindgut specification directly through posteriorizing endoderm and indirectly through promoting the formation of the mesenchymal layers in the in vitro differentiation system.

3.2.Transient Inhibition of Wnt Signaling Blocked the Growth of Organoids

To investigate the effect of transient Wnt activity on the developmental potential of late-stage intestinal organoids, we seeded the spheroids into 3D Matrigel. Dramatic changes occurred within 24 hours after the spheroids were seeded. Under normal conditions, two specific layers with distinct morphologies assembled the organoids. However, we observe the shedding of the outer mesenchymal layer from the surfaces of the spheroids due to inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figure 2A). We proposed that the developmental potential of the outer mesenchymal layer was affected. Indeed, Z-stacked confocal images of the spheroids demonstrate that the expression of Vimentin within the outer mesenchymal layer is reduced due to Wnt signaling inhibition (Figure 2B). Besides, RT-qPCR quantification showed that several other mesenchymal specific genes also exhibited significant decrease after inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figure 2C). Moreover, the spheroids failed to grow after Wnt signaling inhibition (data not shown). However, the epithelium of the spheroids grew into finger-like protrusions within one month under normal differentiation conditions (Figure 2D). Marker analysis showed that virtually all of the gut tube epithelium in the organoids expressed the intestinal master transcription factor CDX2 and the epithelial marker E-Cadherin after 30 days in culture (Figures 2E). Meanwhile, we observed that a few Vimentin+ mesenchymal cells still existed in the periphery of several organoids (Figure 2F). Taken together, these results demonstrated that transient inhibition of Wnt signaling blocked the late-stage growth of organoids through inhibiting the developmental potential of both the mesenchymal layer and the epithelial layer.

3.3.Wnt Signaling Caused Dramatic Transcriptional Changes during Differentiation

To characterize the genome-wide gene expression changes elicited by Wnt signaling during hindgut patterning, we collected DE, DE in media supplemented with FW or FD for RNA isolation. We adopted RNA-seq to characterize the transcriptomes of these three samples because RNA-seq has a higher dynamic range in detecting the low-abundance transcripts than regular microarray analysis. We mapped raw reads (supplemental Table S1) to human reference genome hg19 using TopHat. Next, HTSeq-count was used to compute read counts for each gene. We subsequently performed pairwise comparisons between libraries to identify the differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) by using edge R. Transcripts with greater than 3-fold change (p<0.01) were considered as DETs. Analysis of the complete list of DETs with FPKM (fragments per kilo base of transcript per million) values (Table S2) revealed that the greatest changes in differential gene expression were caused by Wnt signaling and the majority of DETs were Wnt-repressed targets. Of the 4103 DETs, more than half of the genes (240 activated genes and 2023 repressed genes) were regulated by Wnt signaling, and forty percent of the genes (775 activated genes and 858 repressed genes) showed a change in the RNA levels during differentiation (Figure 3A). We also observed an increase in the number of activated genes (from 775 to 1089) after inhibition of Wnt signaling (Figure 3A). A Venn diagram analysis showed that the RNA levels of 1924 Wnt targets (58 activated genes and 1866 repressed genes) were unchanged during differentiation (Figure 3B), and the RNA levels of 1294 transcripts (684 genes activated and 610 genes repressed in the differentiation process) were not regulated by Wnt signaling (Figure 3B). In comparison, fewer gene transcripts (169+13+5+152) were exclusively Wnt targets and showed a change in their RNA levels during differentiation (Figure 3B). Since the gene repertoire of Wnt targets had small overlap with the differentiation-relevant genes, we speculate that other signaling pathways counterbalanced the effects of Wnt signaling in regulating hindgut differentiation.

Figure 3. Wnt signaling caused dramatic transcriptional changes during differentiation.

(A) A Venn diagram shows the shared and unique DETs between the Wnt targets (FW/FD) and the differentiation relevant genes (FW/DE). The overlapping region represents genes which are concomitantly regulated between groups. The directions of transcript level changes are denoted by the upward-pointing and downward-pointing arrows. Blue and pink denote Wnt targets or differentiation relevant genes, respectively. (B) Bar plot representation of differential gene expression between different groups. The greatest changes in differential gene expression are caused by Wnt signaling and the majority of DETs are Wnt-repressed targets. (C) Hierarchical clustering analysis of DETs within the three samples of DE, DE cultured in the media supplemented with FW or FD. The expression values of DETs are shown in the heatmap format. The red, black, and green colors represent higher than average, close to average, and lower than average expression of a particular gene, as measured by row standardized Z-scores. The heatmap is divided into eight discrete clusters and color is coded on the right. (D) IPA demonstrates that clusters of Wnt targets show enrichment in specific biological functions.

In order to compare Wnt target gene expression levels in the differentiation process, we performed hierarchical clustering of DETs and identified eight discrete clusters which showed stage-specific expression patterns (Figure 3C). According to the RNA levels in DE cultures relative to the FW-treated cultures, we separated the late-stage genes (clusters 1 and 3) in response to high level of Wnt activity from the early-stage genes (clusters 4, 6, 7 and 8) in response to low level of Wnt activity (Figure 3C). To analyze the potential functions of Wnt targets in regulating hindgut differentiation, we performed IPA within the major groups of genes. The late-stage Wnt targets were mainly involved in germ layer specification. For example, the activated genes in cluster 1 were involved in functional categories related to differentiation of mesoderm (“development of body axis”, “morphogenesis of skeletal system”, “development of body trunk”) (Figure 3D), and the repressed genes in cluster 3 were involved in functional categories related to “differentiation of hemopoietic system, neural system and immune system” (Figure 3D). In contrary to this, the early-stage Wnt targets may be related with the termination of gastrulation. For example, the repressed genes of early-stage Wnt targets in clusters 4 and 7 were involved in functional categories related to “pluripotency”, “primitive streak formation” and “mesenchymal differentiation” (Figure 3D). The lists of top functional networks (scores>25) (Table S3) show similar function categories, such as “the digestive or skeletal system development” in the late-stage Wnt activated targets. Taken together, IPA analysis suggests that high-level of Wnt signaling can specify the cell fates towards the digestive or muscular lineages and suppress the differentiation towards the neural or immune lineages at late stage, whereas low-level of Wnt signaling is critical for efficient differentiation of hESCs towards DE.

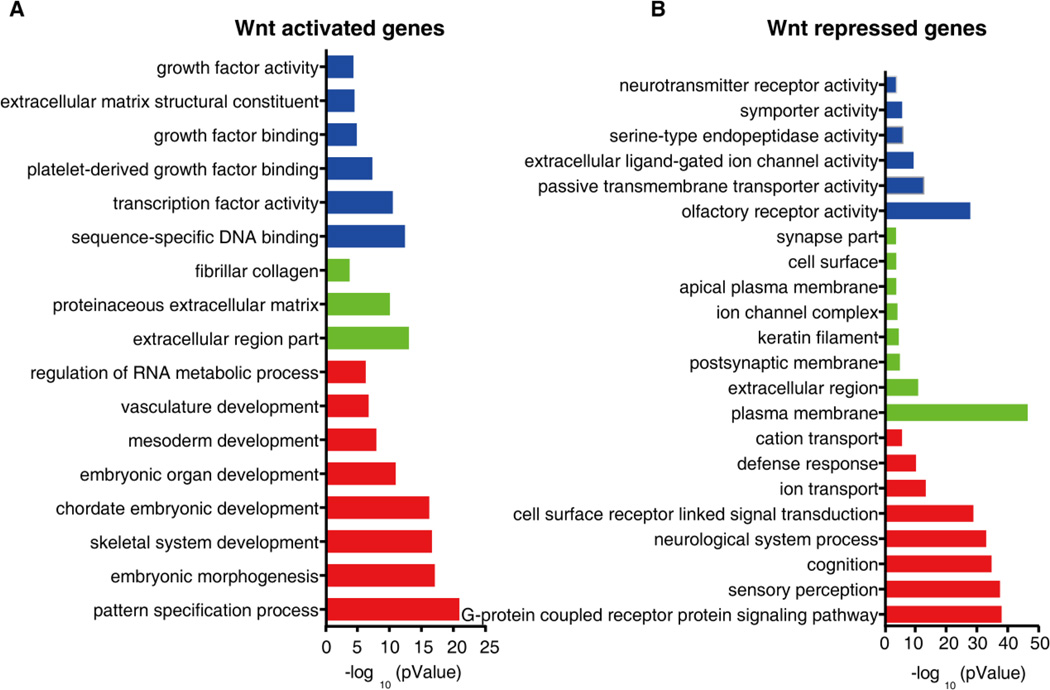

In order to further verify the results of IPA analysis, we performed GO analysis of the Wnt targets and identified the significant GO terms. In the Wnt-activated targets, the most significant GO terms included biological processes related to “pattern specification”, cellular components related to “extracellular matrix” and molecular function related to “transcription factor and growth factor activity” (Figure 4A). Pathway analysis revealed the activation of canonical Wnt signaling and Hh signaling pathways for cell adhesion and migration (“ECM-receptor interaction” and “focal adhesion”) (Figure S3A; Tables S4 and S5). The most significant GO terms in the Wnt-repressed targets included biological processes related to “neurological system process”, cellular components related to “membrane parts” and molecular function related to “olfactory receptor activity” (Figure 4B). The most significant pathways were involved in neural system development (“olfactory transduction”, “ABC transporters” and “neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction”) and immune system development (“complement and coagulation cascades”, “retinol metabolism” and “steroid hormone biosynthesis”) (Figure S3B). In summary, we conclude that the transcriptional changes caused by Wnt signaling are relevant with the critical events during the differentiation of hESCs towards hindgut.

Figure 4. Identify the significant GO terms in the Wnt targets.

The enriched molecular functions GO terms (blue clusters), cellular components GO terms (green clusters) and biological functions GO terms (red clusters) are shown. P value is used to rank the enrichment. (A) The significant GO terms in the Wnt-activated targets demonstrate that multiple Wnt-activated targets are related to embryonic pattern specification. (B) The significant GO terms in the Wnt-repressed targets demonstrate that multiple Wnt-repressed targets are involved in the neural differentiation process.

3.4.Partial CXCR4+CD117+ Cells are Plastic to Express Mesenchymal Genes Activated by Wnt Signaling

We next sought to determine whether the mesenchymal genes activated by Wnt signaling were expressed in the spheroids at day 7 of differentiation. Immunostaining of Wnt targets (FoxF1, PDGFRB, LEF1 and HAND1) on the Day-7 spheroids demonstrated that these mesenchymal proteins were weakly expressed in the spheroids (Figures 5A–5D). To further identify whether the mesenchymal genes activated by Wnt signaling were derived from endoderm or non-endoderm, we differentiated hESCs towards DE and analyzed the expression of the DE markers CXCR4 and CD117 by flow cytometry [37]. Flow cytometric analysis revealed 64.6% CXCR4+CD117+ DE cells and 34.2% CXCR4− non-endoderm cells at day 3 of differentiation (Figure 5E). The CXCR4+CD117+ and CXCR4− populations were isolated by cell sorting and plated as monolayer cultures in the hindgut induction condition. We harvested the differentiated cells and quantified the relative expression of genes by RT-qPCR at day 7 of differentiation. The endodermal markers (SOX17, GATA6 and HNF4A) are highly expressed in the CXCR4+CD117+ cells relative to the CXCR4− cells. Vice versa, the pluripotency marker (OCT4) and primitive streak markers (T and Twist1) are lowly expressed in the CXCR4+CD117+ cells relative to the CXCR4− cells (Figure 5F). Besides, we found several Wnt targets (CDX2, LEF1, MSX2, HAND1 and PDGFRA) were enriched in the CXCR4+CD117+ cells and other Wnt targets (APLNR and HAPLN1) were enriched in the CXCR4− cells (Figure 5F). Therefore, we propose that the CXCR4+CD117+ cells and the CXCR4− cells may respond to Wnt signaling in distinct manners. To identify the differential responses of Wnt signaling in the sorted cell fractions, we compared the relative expression levels of Wnt targets in FW-treated cultures relative to FD-treated cultures. It turns out that the Wnt targets can be activated in both the CXCR4+CD117+ fraction and CXCR4− fraction (Figure 5G). The expression fold change of hindgut marker CDX2 due to Wnt signaling inhibition is significantly higher in the CXCR4+CD117+ fraction (Figure 5G). However, the expression fold changes of LEF1, MSX2, HAND1 and APLNR are much higher in the CXCR4− fraction relative to the CXCR4+CD117+ fraction (Figure 5G). Taken together, we can conclude that at least partial CXCR4+CD117+ cells are still plastic and can be induced to express mesenchymal genes by Wnt signaling in a manner distinct from the CXCR4− cells.

Figure 5. The Wnt targets are differentially activated in the sorted endoderm cells and non-endoderm cells.

(A–D) Immunostaining of Wnt-activated mesenchymal genes (FoxF1, PDGFRB, LEF1 and HAND1) on the spheroids showed weak expression at day 7 of differentiation. Scale bars, 20µm. (E) Day-3 flow cytometry analysis showing expression of CXCR4 and CD117 in the differentiated cultures. Regions used to sort cells into fractions are shown. The sorted cells were plated as monolayers in the hindgut induction condition. (F) Day-7 qPCR analysis detailing the differential expression of pluripotency genes, mesenchymal genes, endodermal genes and Wnt targets in the sorted cell fractions. Data represent the log2 of fold change of expression between CXCR4+CD117+ populations and CXCR4− populations. (G) Day-7 qPCR analysis detailing differential responses of Wnt targets in the sorted cell fractions. Data represent the log2 of fold change of expression between FW-treated cultures and FD-treated cultures.

3.5.TCF7L2 Binds the Regulatory Regions of Embryonic Genes Relevant to Morphogenesis

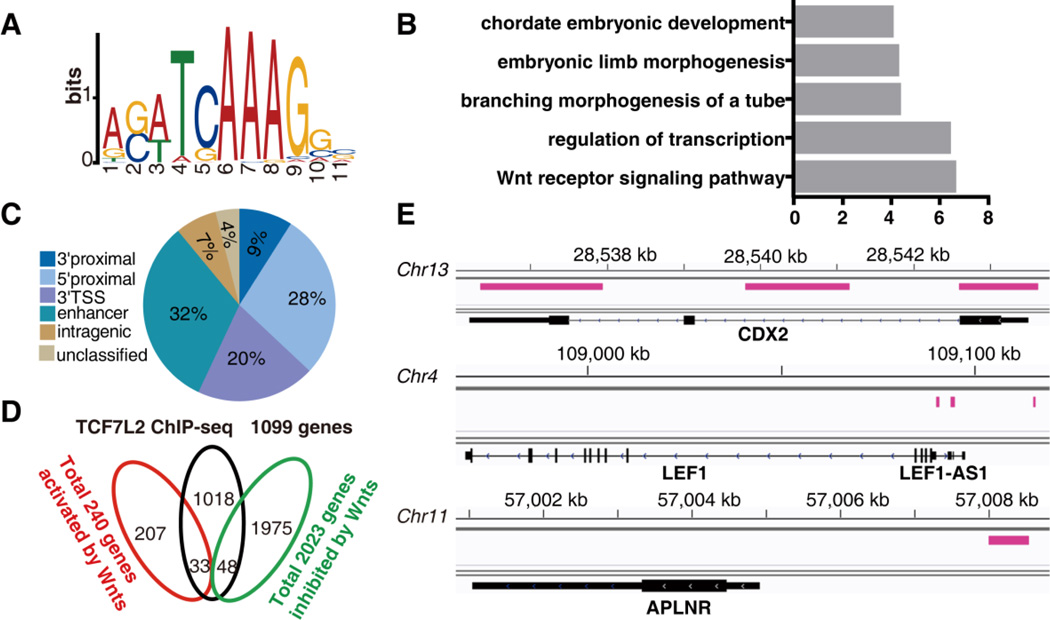

Although we found 2263 genes whose expression levels were altered due to abrogation or activation of the Wnt pathway, it remains unclear whether these genes are direct or indirect targets of the TCF/β-catenin transcription factor complex. TCF7L2 plays a preeminent and evolutionarily conserved role in orchestrating hindgut development, but little is known about the identity of its transcriptional targets in human embryonic development. We therefore combined high-affinity TCF7L2 antibodies with ChIP-seq in an effort to find out those immediate downstream genes that govern human hindgut development. For these studies, we performed ChIP experiments on day 7 of differentiation when large numbers (>90%) of hindgut progenitor cells consistently expressed CDX2. These analyses revealed 2204 TCF7L2 binding regions that mapped to 868 annotated genes (Table S6, sheets1 and 2). In order to clarify whether the human TCF7L2 binding regions had their own unique and enriched binding motif, we performed MEME analysis and identified 1532 instances of the consensus sequence A-C/G-A/T-T-C-A-A-A-G (Figure 6A; Table S6, sheets 3 and 4). 67% (1030) of the binding sites are within ± 20kb relative to the nearest TSSs of 418 genes (Table S6). These genes are typically associated with embryonic morphogenesis, including Wnt pathway components (SFRP5, DVL3, TCF7, NKD1, NKD2, DACT1, CCDC88C, KREMEN1, TLE3, PYGO1, LEF1, Wnt11 and AXIN2), mesendodermal genes (EOMES and MIXL1), hindgut markers (CDX2 and EVX1) and mesenchymal genes (MSX1, MSX2, TBX3 and TBX4). To gain additional insights into the identity of these TCF7L2 targets, we performed GO analysis. Statistically significant GO terms included “regulation of transcription”, “embryonic limb morphogenesis” and “Wnt receptor signaling pathway” (Figure 6B). Consistently, we found that a larger proportion of TCF7L2 binding sites were located within 10kb both upstream and downstream of the nearest TSSs (Figure 6C) in comparison with the colorectal cancer cells [25]. Taken together, these data provide strong evidence that the TCF7L2 targets are necessary for the initial transcription of several embryonic genes relevant to morphogenesis.

Figure 6. TCF7L2 binds the regulatory regions of embryonic morphogenesis relevant genes.

(A) De novo motif analysis via MEME identifies the TCF7L2 binding motif. (B) The significant GO terms in the TCF7L2 targets. P value is used to rank the enrichment. (C) The pie chart illustrates the localization of TCF7L2 binding sites in relation to annotation to the nearest transcription units. Shown are percentages of binding sites in the different locations. (D) Venn diagrams of the number of genes expressed in each condition. Of the 240 genes activated and 2023 genes repressed by Wnt signaling, 33 and 48 genes are bound by TCF7L2, respectively. (E) Representative view of the TCF7L2 binding regions identified by ChIP-seq within the CDX2, LEF1 and APLNR genomic loci. The pink lines denote the genomic locations of TCF7L2 binding peaks.

To investigate whether TCF7L2 exerted functional consequences through regulating the target gene expression, we compared the list of TCF7L2 targets to the list of Wnt targets. Among these 868 TCF7L2 targets, there were only 32 Wnt-activated genes and 51 Wnt-repressed genes, respectively (Figure 6D; Table S7, sheets 1 and 2). Among these 32 Wnt-activated genes, the RNA levels of 21 genes are increased during differentiation. These include hindgut marker CDX2, genes relevant to morphogenesis (MSX1, MSX2, LEF1, SP8, T, PAX2), genes relevant to cell migration (NRP1, PDGFRB, MIXL1), as well as a series of genes (DIO2, RGS4, LYPD6B, DACH1) poorly characterized for their roles in the hindgut development (Figure 6E; Table S7, sheet 3). Noticeably, the RNA level of one cell-surface protein APLNR was activated by Wnt signaling (Table S2, sheet1) and the enhancer region was directly bound by TCF7L2 (Figure 6E).

3.6. Wnt Signaling Directly Promotes the Expression of APLNR in the Mesendoderm-like Cells and Mesenchymal Cells

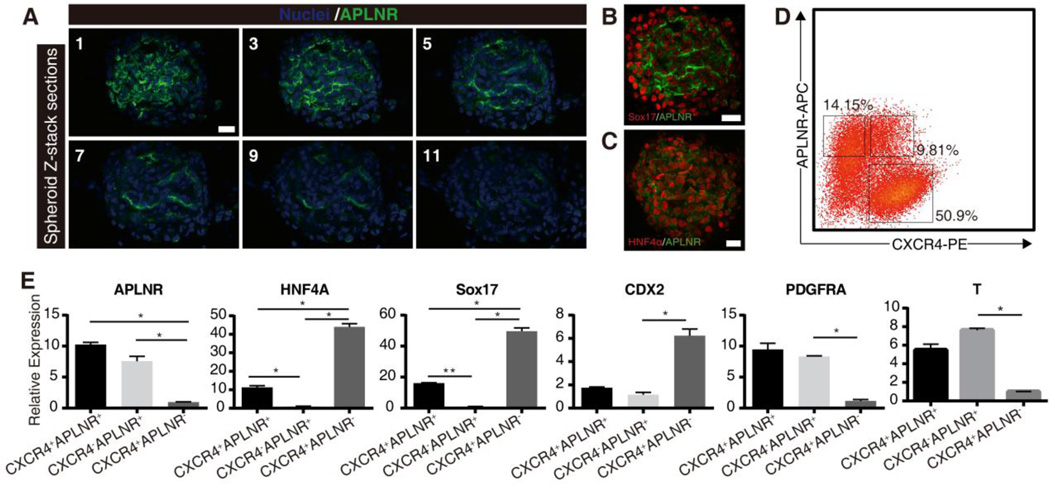

APLNR was expressed in a subpopulation reminiscent of lateral plate mesodermal cells and mesendodermal cells during early embryogenesis [38–40]. Immunostaining with antibody APLNR in the in vitro differentiation system demonstrated that the majority of APLNR+ cells were located on the apical surface of the spheroids (Figure 7A). Partial APLNR+ cells also expressed the endoderm markers HNF4A and SOX17 (Figures 7B and 7C). It was consistent with the result that CXCR4+APLNR+ cells occupied 9.8% of the differentiated cells (Figure 7D). RT-qPCR showed that the mesenchymal specific genes (PDGFRA and T) and the endodermal specific genes (HNF4A and SOX17) were specifically enriched in the APLNR+ or CXCR4+ cells, respectively (Figure 7E). Furthermore, the expression levels of endodermal markers (HNF4A and SOX17) were significantly lower in the CXCR4+APLNR+ cells relative to the CXCR4+APLNR− cells, while the expression levels of mesenchymal markers (PDGFRA and T) showed no significant difference between the CXCR4+APLNR+ cells and the CXCR4−APLNR+ cells (Figure 7E). Therefore, we infer that the CXCR4+APLNR+ cells may resemble the mesendoderm cells. This phenomenon further confirms that Wnt signaling directly promotes the expression of Wnt target genes in the mesendoderm-like cells and the mesenchymal cells. In addition, APLNR can also be used as a negative cell surface marker to purify the differentiated hindgut endoderm cells.

Figure 7. The molecular characteristics of APLNR+ cells reflected the diverse mechanisms of Wnt signaling during differentiation of hESCs to hindgut.

(A) Immunofluoresence staining for APLNR on spheroids (n=5, representative spheroid shown). Images were captured through the spheroid using confocal microscopy (z-series images captured every 2.1 microns). Representative sections through a spheroid (every two slices shown, 4.2 microns between slices) demonstrate that the expression of APLNR is mainly localized on the apical side of the spheroids. Scale bars, 50µm. (B and C) Co-immunostaining with APLNR and endoderm markers (SOX17 or HNF4A) demonstrated that the endodermal specific genes were expressed in several APLNR+ cells. Scale bars, 50µm. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of CXCR4 and APLNR expression in the differentiated cultures. Regions used to sort cells into fractions for further analysis are shown. (E) RT-qPCR analysis of the mesodermal specific genes (PDGFRA, T) or endodermal specific genes (HNF4A, SOX17, and CDX2) in the sorted cell fractions. Results are represented as means ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis is performed with student’s t-test, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

4. Discussion

Multiple Wnt ligands are expressed in the posterior regions of the vertebrate embryos during and shortly after gastrulation [41], and the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling at this stage is to direct endoderm towards a posterior fate and inhibit an anterior fate [1, 42–44]. However, the mechanism of how Wnt signaling activates its downstream target genes to control hindgut development is currently unclear. Here, we use RNA-seq and ChIP-seq to identify direct and indirect target genes of Wnt signaling in differentiated endoderm cells. This study elaborates on the transcriptional response of Wnt signaling during the transition from the 2D sheets of DE into the 3D gut tube-like structures for the first time. Our results lay the foundation for further investigating the mechanisms of the primitive gut tube formation during early embryogenesis.

Low level of Wnt Activity is Critical for Efficient Endoderm Differentiation

Hierarchical clustering analysis of several Wnt targets in the DE cell cultures reveals that several Wnt targets were endogenously activated (Figure 3C). Functional analyses suggest that over-activation of Wnt signaling in the DE cell cultures may delay the end point of gastrulation and endow the DE cells with primitive streak characteristics (Figure 3D). This is in line with a number of other studies demonstrating that Wnt signaling drives primitive streak-like differentiation in vitro [45–48] and acts in parallel with Activin signaling to induce expression of mesodermal marker genes [49]. Previous studies also demonstrated that prolonged Wnt signaling in the anterior primitive streak led to mesoderm induction during hESC differentiation towards DE [50–52]. We speculate that it is critical to keep low levels of Wnt signaling during differentiation of hESC to DE. It will provide an instructive clue for optimizing the differentiation of hESC into intestinal tissues in vitro.

Wnt Signaling Regulated Multi-lineage Differentiation of hESCs

A previous study in the mouse embryos demonstrated that Wnt signaling acted directly on the endoderm to induce transcription of the intestinal master regulator Cdx2 [20]. Here, we provided further evidence that TCF7L2 directly occupied the CDX2 genomic regulatory regions (Figure 6E). We identified a list of transcription factors and signaling molecules related to embryonic pattern specification (Figure 4A; Table S2, sheet4). These genes were divided into well-known hindgut marker genes CDX1, CDX2 and CER1, the mesoderm specific genes HAND1, FoxF1, DLL3, LEF1, HES7, SNAI2, as well as the gastrulation relevant HoxB genes [53]. It seems that Wnt signaling acts on both the endoderm and non-endoderm cells in the in vitro differentiation system. In addition, KEGG pathway analysis indicates the the most significant pathway in the Wnt-activated targets is the Hh signaling pathway (Figure S3A), which was reported to direct reciprocal interactions between the mesoderm and the endoderm [11, 54]. We infer that Wnt signaling may participate in coordinating the endoderm and mesoderm development through activation of Hh signaling. In addition, we also find that the Wnt-repressed targets are related to the neural or immune system development (Figure S3B; Table S2, sheet5). This is in agreement with the previous studies which showed that Wnt mutants exhibited a largely overlapping spectrum of posterior defects and ectopic neural structures [22, 55–57]. Similar phenotype was also observed in mice lacking several Wnt targets such as Cdx, T and Tbx6 [56, 58, 59]. Moreover, the anterior visceral endoderm promoted head formation by producing Wnt antagonists in the anterior region of the embryo [60, 61]. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Wnt signaling promotes hindgut cell fate commitment through the coordination of mesoderm and endoderm development and inhibition of ectoderm development.

APLNR Revealed the Potential Mechanisms of Wnt Signaling in the in vitro Differentiation System

Here, we identified APLNR as one of the novel Wnt targets for the first time. Firstly, our data further confirm the phenomenon that APLNR+CXCR4+ cells show gene expression profiles resembling mesendoderm cells (Figure 7E), which was reported previously [38]. ELA is the recently identified ligand of APLNR and it can promote the movement of mesendoderm by activation of APLNR signaling [40]. ELA knockout zebrafish have endoderm defects and subsequent cardiac malformation [39]. In hESC, ELA is required to maintain a transcriptional profile that is permissive for endoderm development [62]. Together, these data suggest that Wnt-mediated APLNR expression participates in the mesendoderm differentiation. Apart from that, partial APLNR+ cells represent the lateral plate mesoderm which can instruct the endoderm to differentiate [1, 8, 9]. Finally, the aggregation of APLNR+ cells on the apical surface of the spheroids is similar to the flow-dependent expression of APLNR in the newly lumenized vessels [63]. We speculate that the expression of APLNR in the spheroids may be relevant with the establishment of 3D structures during gut tube morphogenesis. In summary, the molecular characteristics of the novel Wnt target APLNR provide potential mechanisms by which Wnt signaling regulates hindgut differentiation.

Combinatorial Analyses of Wnt Direct Targets in Differentiated Endoderm Cells and Colorectal Cancer Cells

Our study correlates the global profile of TCF7L2 binding with the list of Wnt targets to provide a view of the direct targets of the Wnt pathway in the differentiated endoderm cell cultures. Comparing the list of 868 TCF7L2 targets to the list of 240 Wnt-activated targets, we found that only 13.3% (32/240) of the genes activated by Wnt signaling were bound by TCF7L2 (Table S7, sheet1). Many indirect targets are likely to exist in the Wnt-activated genes. Besides, the motif generated from the TCF7L2 binding sites is the same with the previously identified motif through other in vitro or in vivo experiments [25, 64]. However, the TCF7L2 binding profiles are context-dependent. Among the 2204 TCF7L2 binding regions, 16.8% (370) overlap with 4793 binding regions previously identified in the colorectal cancer cells (Table S7, sheet4). The small percentage of overlap reflects the context-dependent role of TCF7L2. However, the conserved feedback mechanism still exists in the Wnt signaling. David functional analysis identifies Wnt pathway as one of the significant pathways enriched in these overlapping genes (Table S7, sheet5). Taken together, our study establishes a database of the direct and indirect Wnt targets during hindgut differentiation from hESCs and provides instructive information for studying the mechanisms of both early embryogenesis and carcinogenesis.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our study provides genome-wide gene expression profiles in response to Wnt signaling during differentiation of hESC to hindgut. Combinatorial analysis of the TCF7L2 binding profile with Wnt-regulated genes allows the delineation of the direct Wnt targets and the Wnt signal responsive genomic regions in the differentiated cultures. Wnt signaling controls hindgut cell fate specification through direct activation of hindgut markers and indirect regulation of mesodermal and ectodermal lineage genes. Our data provide novel insights into the mechanisms by which Wnt signaling controls hindgut cell fate determination.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Transient inhibition of WNT signal leads to defects in hindgut morphogenesis.

RNA-seq and ChIP-seq were performed to identify direct and indirect WNT targets.

The WNT target genes are composed of multi-lineage genes.

The heterogeneity of APLNR+ cells reflected the diverse mechanisms of WNT signal.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Lorraine Ray for comments on the article. HESC is a generous gift from Dr. Baoyang Hu. We appreciate Yun Qi, Yueqin Guo and other members of our lab for discussion and help. We thank Bing Zhang, Caixia Yu and other members in Beijing Institute of Genomics for their kind advice and help. We thank Qing Meng and Hua Qin for technique guidance on flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571507, 81361120382 and 31371464), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant (XDA01010101), and NIH grants (2R01GM063891 and 1R01GM087517).

Abbreviation

- hESC

human embryonic stem cell

- RNA-seq

deep-transcriptome sequencing

- ChIP-seq

chromatin immunoprecipitation and deep sequencing

- IPA

Ingenuity pathway analysis

- DE

definitive endoderm

- GO

gene ontology

- RA

Retinoic Acid

- Hh

Hedgehog

- DAVID

the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 3D

three-dimensional

- DETs

differentially expressed transcripts

- FW

FGF4+Wnt3a

- FD

FGF4+Dkk1

- TSS

transcription start site

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zorn AM, Wells JM. Vertebrate endoderm development and organ formation. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2009;25:221–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grapin-Botton A, Constam D. Evolution of the mechanisms and molecular control of endoderm formation. Mechanisms of development. 2007;124:253–278. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum M, Feistel K, Thumberger T, Schweickert A. The evolution and conservation of left-right patterning mechanisms. Development. 2014;141:1603–1613. doi: 10.1242/dev.100560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grapin-Botton A, Melton DA. Endoderm development: from patterning to organogenesis. Trends in genetics: TIG. 2000;16:124–130. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremblay KD, Zaret KS. Distinct populations of endoderm cells converge to generate the embryonic liver bud and ventral foregut tissues. Developmental biology. 2005;280:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin V, Khoo PL, Bildsoe H, Wong N, Lewis S, Tam PP. Regionalisation of the endoderm progenitors and morphogenesis of the gut portals of the mouse embryo. Mechanisms of development. 2008;125:587–600. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomason RT, Bader DM, Winters NI. Comprehensive timeline of mesodermal development in the quail small intestine. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2012;241:1678–1694. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells JM, Spence JR. How to make an intestine. Development. 2014;141:752–760. doi: 10.1242/dev.097386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spence JR, Lauf R, Shroyer NF. Vertebrate intestinal endoderm development. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2011;240:501–520. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Apelqvist A, Ahlgren U, Edlund H. Sonic hedgehog directs specialised mesoderm differentiation in the intestine and pancreas. Current biology : CB. 1997;7:801–804. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walton KD, Warner J, Hertzler PH, McClay DR. Hedgehog signaling patterns mesoderm in the sea urchin. Developmental biology. 2009;331:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukui A, Goto T, Kitamoto J, Homma M, Asashima M. SDF-1 alpha regulates mesendodermal cell migration during frog gastrulation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;354:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizoguchi T, Verkade H, Heath JK, Kuroiwa A, Kikuchi Y. Sdf1/Cxcr4 signaling controls the dorsal migration of endodermal cells during zebrafish gastrulation. Development. 2008;135:2521–2529. doi: 10.1242/dev.020107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair S, Schilling TF. Chemokine signaling controls endodermal migration during zebrafish gastrulation. Science. 2008;322:89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1160038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ober EA, Olofsson B, Makinen T, Jin SW, Shoji W, Koh GY, Alitalo K, Stainier DY. Vegfc is required for vascular development and endoderm morphogenesis in zebrafish. EMBO reports. 2004;5:78–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsui T, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Callol-Massot C, Capdevila J, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Noncanonical Wnt signaling regulates midline convergence of organ primordia during zebrafish development. Genes & development. 2005;19:164–175. doi: 10.1101/gad.1253605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells JM, Melton DA. Early mouse endoderm is patterned by soluble factors from adjacent germ layers. Development. 2000;127:1563–1572. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horb ME, Slack JM. Endoderm specification and differentiation in Xenopus embryos. Developmental biology. 2001;236:330–343. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar M, Jordan N, Melton D, Grapin-Botton A. Signals from lateral plate mesoderm instruct endoderm toward a pancreatic fate. Developmental biology. 2003;259:109–122. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherwood RI, Maehr R, Mazzoni EO, Melton DA. Wnt signaling specifies and patterns intestinal endoderm. Mechanisms of development. 2011;128:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemp C, Willems E, Abdo S, Lambiv L, Leyns L. Expression of all Wnt genes and their secreted antagonists during mouse blastocyst and postimplantation development. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2005;233:1064–1075. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregorieff A, Grosschedl R, Clevers H. Hindgut defects and transformation of the gastro-intestinal tract in Tcf4(−/−)/Tcf1(−/−) embryos. The EMBO journal. 2004;23:1825–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lickert H, Kutsch S, Kanzler B, Tamai Y, Taketo MM, Kemler R. Formation of multiple hearts in mice following deletion of beta-catenin in the embryonic endoderm. Developmental cell. 2002;3:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, Oving I, Hurlstone A, van der Horn K, Batlle E, Coudreuse D, Haramis AP, Tjon-Pon-Fong M, Moerer P, van den Born M, Soete G, Pals S, Eilers M, Medema R, Clevers H. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatzis P, van der Flier LG, van Driel MA, Guryev V, Nielsen F, Denissov S, Nijman IJ, Koster J, Santo EE, Welboren W, Versteeg R, Cuppen E, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Stunnenberg HG. Genome-wide pattern of TCF7L2/TCF4 chromatin occupancy in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2732–2744. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02175-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbst A, Jurinovic V, Krebs S, Thieme SE, Blum H, Goke B, Kolligs FT. Comprehensive analysis of beta-catenin target genes in colorectal carcinoma cell lines with deregulated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. BMC genomics. 2014;15:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon RT, Kohn AD, De Ferrari GV, Kaykas A. WNT and beta-catenin signalling: diseases and therapies. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2004;5:691–701. doi: 10.1038/nrg1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development. 2009;136:3205–3214. doi: 10.1242/dev.033910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCracken KW, Howell JC, Wells JM, Spence JR. Generating human intestinal tissue from pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1920–1928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Amour KA, Agulnick AD, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Kroon E, Baetge EE. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, Hoskins EE, Kalinichenko VV, Wells SI, Zorn AM, Shroyer NF, Wells JM. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2010;470:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gracz AD, Ramalingam S, Magness ST. Sox9 expression marks a subset of CD24-expressing small intestine epithelial stem cells that form organoids in vitro. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2010;298:G590–G600. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00470.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, Hoskins EE, Kalinichenko VV, Wells SI, Zorn AM, Shroyer NF, Wells JM. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bafico A, Liu G, Yaniv A, Gazit A, Aaronson SA. Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow. Nature cell biology. 2001;3:683–686. doi: 10.1038/35083081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng X, Ying L, Lu L, Galvao AM, Mills JA, Lin HC, Kotton DN, Shen SS, Nostro MC, Choi JK, Weiss MJ, French DL, Gadue P. Self-renewing endodermal progenitor lines generated from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:371–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu QC, Hirst CE, Costa M, Ng ES, Schiesser JV, Gertow K, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG. APELIN promotes hematopoiesis from human embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2012;119:6243–6254. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-396093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chng SC, Ho L, Tian J, Reversade B. ELABELA: a hormone essential for heart development signals via the apelin receptor. Dev Cell. 2013;27:672–680. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pauli A, Norris ML, Valen E, Chew GL, Gagnon JA, Zimmerman S, Mitchell A, Ma J, Dubrulle J, Reyon D, Tsai SQ, Joung JK, Saghatelian A, Schier AF. Toddler: an embryonic signal that promotes cell movement via Apelin receptors. Science. 2014;343:1248636. doi: 10.1126/science.1248636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin BL, Kimelman D. Wnt signaling and the evolution of embryonic posterior development. Current biology : CB. 2009;19:R215–R219. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLin VA, Rankin SA, Zorn AM. Repression of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the anterior endoderm is essential for liver and pancreas development. Development. 2007;134:2207–2217. doi: 10.1242/dev.001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherwood RI, Chen TY, Melton DA. Transcriptional dynamics of endodermal organ formation. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2009;238:29–42. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engert S, Burtscher I, Liao WP, Dulev S, Schotta G, Lickert H. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling regulates Sox17 expression and is essential for organizer and endoderm formation in the mouse. Development. 2013;140:3128–3138. doi: 10.1242/dev.088765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faunes F, Hayward P, Descalzo SM, Chatterjee SS, Balayo T, Trott J, Christoforou A, Ferrer-Vaquer A, Hadjantonakis AK, Dasgupta R, Arias AM. A membrane-associated beta-catenin/Oct4 complex correlates with ground-state pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development. 2013;140:1171–1183. doi: 10.1242/dev.085654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blauwkamp TA, Nigam S, Ardehali R, Weissman IL, Nusse R. Endogenous Wnt signalling in human embryonic stem cells generates an equilibrium of distinct lineage-specified progenitors. Nature communications. 2012;3:1070. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sumi T, Oki S, Kitajima K, Meno C. Epiblast ground state is controlled by canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the postimplantation mouse embryo and epiblast stem cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e63378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mendjan S, Mascetti VL, Ortmann D, Ortiz M, Karjosukarso DW, Ng Y, Moreau T, Pedersen RA. NANOG and CDX2 pattern distinct subtypes of human mesoderm during exit from pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:310–325. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernardo AS, Faial T, Gardner L, Niakan KK, Ortmann D, Senner CE, Callery EM, Trotter MW, Hemberger M, Smith JC, Bardwell L, Moffett A, Pedersen RA. BRACHYURY and CDX2 mediate BMP-induced differentiation of human and mouse pluripotent stem cells into embryonic and extraembryonic lineages. Cell stem cell. 2011;9:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gadue P, Huber TL, Paddison PJ, Keller GM. Wnt and TGF-beta signaling are required for the induction of an in vitro model of primitive streak formation using embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:16806–16811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603916103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loh KM, Ang LT, Zhang J, Kumar V, Ang J, Auyeong JQ, Lee KL, Choo SH, Lim CY, Nichane M, Tan J, Noghabi MS, Azzola L, Ng ES, Durruthy-Durruthy J, Sebastiano V, Poellinger L, Elefanty AG, Stanley EG, Chen Q, Prabhakar S, Weissman IL, Lim B. Efficient endoderm induction from human pluripotent stem cells by logically directing signals controlling lineage bifurcations. Cell stem cell. 2014;14:237–252. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iimura T, Pourquie O. Collinear activation of Hoxb genes during gastrulation is linked to mesoderm cell ingression. Nature. 2006;442:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature04838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao J, Kim BM, Rajurkar M, Shivdasani RA, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling controls mesenchymal growth in the developing mammalian digestive tract. Development. 2010;137:1721–1729. doi: 10.1242/dev.044586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galceran J, Farinas I, Depew MJ, Clevers H, Grosschedl R. Wnt3a−/−-like phenotype and limb deficiency in Lef1(−/−)Tcf1(−/−) mice. Genes & development. 1999;13:709–717. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van de Ven C, Bialecka M, Neijts R, Young T, Rowland JE, Stringer EJ, Van Rooijen C, Meijlink F, Novoa A, Freund JN, Mallo M, Beck F, Deschamps J. Concerted involvement of Cdx/Hox genes and Wnt signaling in morphogenesis of the caudal neural tube and cloacal derivatives from the posterior growth zone. Development. 2011;138:3451–3462. doi: 10.1242/dev.066118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshikawa Y, Fujimori T, McMahon AP, Takada S. Evidence that absence of Wnt-3a signaling promotes neuralization instead of paraxial mesoderm development in the mouse. Developmental biology. 1997;183:234–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE. Three neural tubes in mouse embryos with mutations in the T-box gene Tbx6. Nature. 1998;391:695–697. doi: 10.1038/35624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pennimpede T, Proske J, Konig A, Vidigal JA, Morkel M, Bramsen JB, Herrmann BG, Wittler L. In vivo knockdown of Brachyury results in skeletal defects and urorectal malformations resembling caudal regression syndrome. Developmental biology. 2012;372:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, Monaghan AP, Blumenstock C, Niehrs C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature. 1998;391:357–362. doi: 10.1038/34848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kimura-Yoshida C, Nakano H, Okamura D, Nakao K, Yonemura S, Belo JA, Aizawa S, Matsui Y, Matsuo I. Canonical Wnt signaling and its antagonist regulate anterior-posterior axis polarization by guiding cell migration in mouse visceral endoderm. Developmental cell. 2005;9:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ho L, Tan SY, Wee S, Wu Y, Tan SJ, Ramakrishna NB, Chng SC, Nama S, Szczerbinska I, Chan YS, Avery S, Tsuneyoshi N, Ng HH, Gunaratne J, Dunn NR, Reversade B. ELABELA Is an Endogenous Growth Factor that Sustains hESC Self-Renewal via the PI3K/AKT Pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Papangeli I, Kim J, Maier I, Park S, Lee A, Kang Y, Tanaka K, Khan OF, Ju H, Kojima Y, Red-Horse K, Anderson DG, Siekmann AF, Chun HJ. MicroRNA 139-5p coordinates APLNR-CXCR4 crosstalk during vascular maturation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11268. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hallikas O, Palin K, Sinjushina N, Rautiainen R, Partanen J, Ukkonen E, Taipale J. Genome-wide prediction of mammalian enhancers based on analysis of transcription-factor binding affinity. Cell. 2006;124:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.