Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and durability of a therapist-supported method for computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy (CCBT) in comparison to standard CBT.

Method

154 drug-free patients with MDD seeking treatment at two university clinics were randomly assigned to either 16 weeks of standard CBT (up to twenty 50-minute sessions) or CCBT using the Good Days Ahead program. The amount of therapist time in CCBT was planned to be about one third that in CBT. Outcomes were assessed by independent raters and self-report at baseline, weeks 8 and 16, and at 3 and 6 months post-treatment. The primary test of efficacy was noninferiority on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) at week 16.

Results

Approximately 80% of patients completed the 16-week protocol (CBT: 79%; CCBT: 82%). CCBT met a priori criteria for noninferiority to conventional CBT at week 16. The groups did not differ significantly on any measure of psychopathology. Remission rates also were similar for the two groups (ITT rates: 41.6%[CBT], 42.9%[CCBT]). Both groups maintained improvements throughout the follow-up.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that a method of CCBT that blends internet-delivered skill-building modules with about 5 hours of therapeutic contact was noninferior to a conventional course of CBT that provided over 8 hours of additional therapist contact. Future studies should focus on dissemination and optimizing therapist support methods to maximize public health significance.

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) is one of the best established nonpharmacological treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD).1,2 Meta-analyses of a large number of randomized controlled trials have shown that a 12-16 week course of individual CBT has efficacy comparable to antidepressant pharmacotherapy,3–5 with fewer relapses after treatment is stopped.6,7 CBT also may significantly improve treatment outcomes when used in combination with pharmacotherapy,8,9 especially for patients with more severe or treatment resistant depressive disorders.10,11 Despite compelling justification for widespread use of CBT, there are significant barriers to providing this form of therapy in everyday practice. One barrier to broader dissemination is an insufficient number of trained therapists, particularly in rural and public mental health settings.12 Other constraints are the cost of treatment and difficulties in scheduling and attending a large number of 50-minute therapy sessions across 3-4 months. These limitations help to explain why antidepressant pharmacotherapy – not CBT – continues to be the most commonly used treatment for depressive disorders.13

Computer-assisted cognitive behavior therapy (CCBT) is a strategy that could make therapy more widely available and reduce cost, as well as provide learning experiences and data tracking features that might enhance standard CBT.14 Although the development of CCBT can be traced back more than 20 years,15,16 activity in this area has increased over the past decade, particularly following the introduction of multimedia programs that can be accessed via the internet.17–19 Meta-analyses of a steadily growing research literature have documented the efficacy and efficiency of CCBT.20–24 However, evidence to date indicates that stand-alone programs that do not provide therapeutic support – representing about 40% of controlled studies - typically have much smaller effects than those that include at least a modest amount of clinician time.23 For example, in a recent primary care study25 that provided participants with a small amount of technical support and no support from a clinician, neither of the two forms of CCBT that were studied was more effective than treatment as usual. Although it appears that some amount of clinical support is important, it is unclear what amount of therapist contact is optimal. In studies that do provide therapeutic support, the average amount of support typically has ranged from one to five hours.20,23

The method of CCBT used in the current investigation was designed to integrate computer delivered training with therapist support to substantially reduce the amount of therapist time and effort required to deliver an effective course of therapy. It is a nine module, multimedia program (Good Days Ahead [GDA]19) that has shown promise in two open studies26,27 and a small randomized, controlled trial.28 In the latter study, 45 drug-free outpatients with MDD were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of treatment with conventional CBT (nine 50-minute sessions of individual therapy), CCBT plus about four hours of therapist support, or a waiting list control group. At post-treatment, both treatment groups obtained clinically meaningful improvements compared to the waiting list control group; the substantial reductions in depressive symptoms observed in the CBT and CCBT groups (Cohen’s d =1.04 for CBT and 1.14 for CCBT) were maintained across a six month follow-up.28 Although that preliminary study was not designed to test noninferiority, the results suggested that this approach to CCBT might produce results that are comparable to individual CBT.

The current study was designed to conduct a more rigorous test of this method of therapist-supported CCBT. To ensure that the design was sensitive to any potential advantage for conventional therapy, patients treated with individual CBT received up to 20 sessions across 16 weeks of acute phase therapy. The CCBT group, by contrast, received only about one third the amount of therapist contact as those in the comparison group. To minimize potential allegiance effects (JHW led the development of GDA at the Louisville site), investigators with high allegiance to conventional CBT (MET;GKB) led the University of Pennsylvania site (where Beck developed his model of CBT). Study therapists were selected for their expertise in conventional CBT and trained on the CCBT method so that they could provide both interventions. Finally, the study’s sample size was determined to conduct a formal statistical test of noninferiority. The main hypothesis was that CCBT would be noninferior to a full course of CBT on the primary study outcome.

METHODS

The study was conducted at the Departments of Psychiatry of the medical schools of the University of Louisville and the University of Pennsylvania. All study methods were specified in advance of subject recruitment and were approved by the institutional review boards of the two sites. Prospective participants were recruited via advertisements and from the clinical services of the participating sites; online recruitment was not used in this study. After providing written informed consent, potentially eligible subjects were diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).29 Subjects were excluded if they: (a) had severe or poorly controlled concurrent medical disorders that would interfere with participation; (b) met criteria for any of the following concurrent DSM-IV disorders: any psychotic or organic mental disorder, bipolar disorder, active alcohol or drug dependence, primary anxiety disorder or primary eating disorders (primary refers to the diagnosis associated with the most functional impairment), attention deficit disorder, learning disorder, borderline personality disorder, or antisocial or paranoid personality disorder; (c) scored less than 14 on the first 17 items of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD)30 at either the screening or baseline (week 0) visit; (d) could not complete questionnaires written in English; (e) had not completed at least a 10th grade education or a GED; or (f) scored below the 9th grade reading level on the Wide Range Achievement Test.31

Participants also were excluded if they were considered to be an immediate active suicide risk (e.g., a score of 3 or 4 on HAMD item 3), they had previously failed to respond to a trial of at least 8 weeks of CBT, or were currently taking antidepressant medications and were either unable or unwilling to discontinue these medications. For the several consenting patients who wanted to stop taking a psychotropic medication, study physicians supervised a tapering and wash-out such that all participants were drug-free for psychotropic medications for at least 1 week prior to randomization. Thus, patients who could not be quickly and safely withdrawn from psychotropic medications were not eligible for randomization.

Concurrent with the SCID, patients’ medical histories were reviewed by a study physician and, when clinically indicated, a physical examination and appropriate laboratory tests were obtained to ensure that patients were medically eligible.

Patients were allocated at each site to the CCBT or CBT arms using a web-based randomization procedure overseen by the University of Pittsburgh Epidemiology Data Center. Because symptom severity and chronicity have been found to moderate response to CBT in some studies,10,32,33 randomization was stratified for these variables in addition to site.

Study Therapists and Therapies

Cognitive Behavior Therapists

A total of 9 therapists (6 at the University of Pennsylvania and 4 at the University of Louisville) participated in the study. Therapists were experienced in delivery of standard CBT and demonstrated competence by scoring at least 40 on the Cognitive Therapy Scale (CTS)34 throughout the study. Two of the therapists at the University of Louisville had previous experience with the GDA software, but none of the other therapists had treated patients with CCBT before the current study. After attending a training workshop conducted by one of the investigators (JHW), they successfully treated at least one patient with CCBT before beginning to treat study patients. During the course of the study, ongoing consultation was provided for all therapists at both sites, jointly, during weekly conference calls conducted by experts in each particular method (CBT: GKB; CCBT: JHW). Specific feedback was provided whenever therapists’ CTS total scores fell below 40 and whenever therapists deviated from the session time-limits for each mode of therapy.

Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CCBT)

The 16-week CCBT protocol consisted of the 9 internet-delivered modules of GDA19 and 12 sessions with a therapist (see below). The modules provided a sequential grounding in the methods of CBT, ranging from behavioral activation to recognizing and addressing dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs. The final module covered relapse prevention. The modules used a blend of video illustrations, psychoeducation from a psychiatrist-narrator, feedback to users, mood graphs to measure progress, interactive skill-building exercises that help users apply CBT methods in daily life, and quizzes to assess comprehension and promote learning. Each module took about 25 minutes to complete; although patients were encouraged to work through the program at their own pace. A clinician dashboard allowed therapists to assess progress, view learning exercises, and facilitate coordination of the human and computer elements of treatment. The first 8 weeks of the protocol delivered the same “dose” of CCBT provided in the earlier study of Wright et al.28 The initial session with the therapist lasted 50 minutes and provided both an overview of CBT and an introduction to using GDA. The next 7 weekly therapy sessions were 25 minutes long. Therapists reviewed the material covered in the module and self-help assignments as a springboard to apply CBT methods to specific problem areas identified by the patient. During the second 8 weeks, patients received four 25 minute “booster” sessions with their therapist and could use the CCBT modules ad lib to facilitate mastery of material. Thus, across 16 weeks, a patient could receive up to 325 minutes total contact with a therapist.

Standard Cognitive Behavior Therapy

CBT was conducted according to the methods of Beck et al.35 as updated by J. Beck36 and Wright, Basco, and Thase.37 The relatively intensive 16-week, 20-session protocol used in the earlier studies of Thase et al.32,33 was chosen to maximize the contrast between the two forms of therapy. Fifty-minute sessions were held twice weekly for the first four weeks and then weekly for the next 12 weeks. The standard CBT protocol thus consisted of up to 1,000 minutes of therapist contact, approximately three times the therapist contact provided in CCBT.

Therapy completion rates were defined as attending at least two thirds of treatment sessions (14/20 in CBT; 8/12 with therapist and 6/9 computer modules in CCBT).

Dependent Measures

Depression Symptom Severity

The principal symptom severity measure was the 17-item HAMD, with the week 16 score serving as the primary outcome measure. HAMD ratings were conducted by independent clinical evaluators without knowledge of treatment assignment. Reliability of raters was established before the study and calibrated annually (via an exchange of video recordings) to prevent rater “drift.” All raters achieved and maintained intraclass correlation coefficients of >0.8. Two well-validated self-report measures, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)38 and the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-SR),39 were used to obtain patients’ perspectives of symptomatic outcome. These assessments were obtained at baseline (week 0), weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 of the treatment protocol, as well as at the two follow-up assessments (see below).

Maladaptive Cognitions

The self-report battery included the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ)40 and the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS),41 which were completed at baseline and weeks 8 and 16 of the treatment protocol and repeated at months 3 and 6 of the follow-up.

Interpersonal Functioning

The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP)42 was completed at pre- and post-treatment of the acute phase and at both follow-up evaluations. This self-report scale provides a global rating of patients’ difficulties in their relationships.

Global Assessment of Functioning

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale43 was completed at baseline, at week 16, and at months 3 and 6 of the follow-up. Although this assessment does not fully uncouple functioning from the impact of depressive symptoms, it is used widely to gauge patients’ adaptation at work and home.

Knowledge about Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Patients completed the Cognitive Therapy Awareness Scale (CTAS)28 pre- and post-treatment and at months 3 and 6 of the follow-up. This 40-item true-false test measures knowledge about the principles and methods of CBT.

Follow-up

Follow-up evaluations were conducted 3 and 6 months after completion of treatment. At the start of the follow-up, participants who had not responded to study treatment received referrals for alternate therapies. Participants who desired ongoing CBT were not permitted to see their study therapists, but they did receive referrals to other therapists if requested.

Statistical Analyses

The target sample size (N=172) was chosen to yield adequate statistical power to test for noninferiority of CCBT versus conventional CBT at week 16. Noninferiority was based on the assumption that, in treatment studies contrasting CBT with both an active antidepressant therapy and a placebo, the expected difference is typically a small-to-moderate effect size, on the order of 4 points on the HAMD, which can represent a meaningful effect at the patient level.44 With a noninferiority design, a type I error rate at .025 (reflecting tests at week 16 and month 6), a standard deviation of the Hamilton score of 8, and the assumption that less than a four-point difference in the means (+/− 4 points) would indicate equivalence, 86 subjects per cell were needed to achieve 80% power. Our final enrollment (N=154) was about 10% below this goal, which reduced statistical power to 76%.

All analyses of continuous outcome variables were based on the intention-to-treat principle. To account for the impact of the subjects who dropped out, a multiple imputation method was used.45 Five complete data sets were generated using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method with a single chain to create five different imputations of missing data. The results from the 5 complete data sets were then combined and averages were calculated to estimate the missing scores in the analyses of continuous measures.

To test the equivalence of CCBT and CBT, a confidence interval approach was used to make the desired outcome of the trial clear. A 95% confidence interval was estimated for the difference in the HAMD means of the two groups at the 16 week assessment point. CCBT would be considered to be noninferior to CBT if the upper (or lower) confidence limit was less than (or greater than) the size of the difference of the means. If significant treatment effects were identified, post-hoc pair-wise comparisons adjusting the type I error rate for multiplicity were planned.

We also tested the moderating effects of site, pretreatment severity, and chronicity on the HAMD, both as main effects and in interaction with treatment. We next compared the two treatments on the self-report measures of depressive symptoms, automatic negative thoughts, global functioning, and interpersonal problems. Mixed-effects regression models were used to examine the effects of CCBT versus CBT. Separate models were fit for each outcome and each model included random effects for intercept and time and fixed effects for treatment. As a second step for each outcome, a time-by-treatment interaction was investigated by adding the two-way interaction between time and treatment into the model.

Remission on the HAMD at week 16 was defined as a score of 7 or lower. During follow-up, a relapse was declared if a formerly remitted patient again met criteria for MDD. Remission and Relapse rates were compared in the ITT and Observed Cases samples with two-sided Fisher’s Exact Tests.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The sample included 154 randomized patients (see CONSORT figure in online supplement). There were no significant differences in baseline patient characteristics between the two treatment groups. Overall, the average patient was about 45-years-old, two thirds of the participants were female, three quarters identified themselves as white, and a little more than one half had attended at least some college (see Table 1). Slightly more than half of the patients had chronic depression and nearly 50% of the participants scored 20 or higher on the pretreatment HAMD score.

Table 1.

Pre-treatment Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total | CBT | CCBT | Test Statistic | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic/Social | n | Mean (SD) |

n | Mean (SD) |

n | Mean (SD) |

||

| Age (in years) | 154 | 46.3 (14.3) | 77 | 46(13.7) | 77 | 46.5 15.1) | t(152) = −0.21 | 0.83 |

| Age at onset of 1st episode | 144 | 24.5 (13.9) | 74 | 22.9(13.3) | 70 | 26.1 (14.5) | t(142) = −1.37 | 0.17 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Race | χ2(2) = 2.62 | 0.27 | ||||||

| White | 117 | 76.0 | 55 | 71.4 | 62 | 80.5 | ||

| Black | 32 | 20.8 | 20 | 26.0 | 12 | 15.6 | ||

| Other | 5 | 3.2 | 2 | 2.6 | 3 | 3.9 | ||

| Hispanic | χ2(1) = 0.10 | 0.75 | ||||||

| No | 143 | 92.9 | 71 | 92.2 | 72 | 93.5 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 7.1 | 6 | 7.8 | 5 | 6.5 | ||

| Gender | χ2(1) = 0.12 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Male | 52 | 33.8 | 25 | 32.5 | 27 | 35.1 | ||

| Female | 102 | 66.2 | 52 | 67.5 | 50 | 64.9 | ||

| Marital Status | χ2(3) = 3.82 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Never Married | 63 | 40.9 | 36 | 46.7 | 27 | 35.0 | ||

| Married/Cohabitating | 47 | 30.5 | 21 | 27.3 | 26 | 33.8 | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 36 | 23.4 | 18 | 23.4 | 18 | 23.4 | ||

| Widowed | 8 | 5.2 | 2 | 2.6 | 6 | 7.8 | ||

| Employment Status | χ2(2) = 0.64 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 62 | 40.3 | 33 | 42.9 | 29 | 37.7 | ||

| Employed | 80 | 52.0 | 39 | 50.6 | 41 | 53.2 | ||

| Retired | 12 | 7.7 | 5 | 6.5 | 7 | 9.1 | ||

| Education | χ2(2) = 1.01 | 0.60 | ||||||

| < High School | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| High School but < College | 68 | 44.1 | 34 | 44.2 | 34 | 44.2 | ||

| ≥College | 85 | 55.2 | 42 | 54.5 | 43 | 55.8 | ||

| Clinical Site | χ2(1) = 0.03 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Penn | 63 | 40.9 | 31 | 40.3 | 32 | 41.6 | ||

| Louisville | 91 | 59.1 | 46 | 59.7 | 45 | 58.4 | ||

| Annual household income | χ2(2) = 1.83 | 0.40 | ||||||

| < $30,000 | 63 | 46.7 | 35 | 52.2 | 28 | 41.2 | ||

| $30,000 - < $60,000 | 38 | 28.1 | 16 | 23.9 | 22 | 32.3 | ||

| ≥$60,000 | 34 | 25.2 | 16 | 23.9 | 18 | 26.5 | ||

| Number of depressive episodes (Life) | 89 | 4.3 (5.7) | 41 | 3.7 (3) | 48 | 4.8 (7.2) | t(87) = −0.99 | 0.32 |

Treatment Completion Rates

Treatment completion rates did not differ for the two interventions (CBT: 79.2%; CCBT: 81.8%). The CCBT group completed an average of 8.1 (sd=2.1) computer modules and received an average of 11.0 (sd=3.0) sessions with their therapist (5.0 hours total). Patients in the CBT group attended an average of 16.0 (sd=5.0) therapy sessions (13.3 hours total). The CCBT group thus received 37% of the therapeutic contact of the CBT group. There were two serious adverse events in the CBT arm that led to premature study termination (hospitalization after a panic attack and death following an emergency hospitalization for open heart surgery). There were also two serious adverse events among patients allocated to the CCBT arm that did not result in study termination (one patient was victim of domestic violence and another took an overdose of a small number of acetaminophen tablets during the follow-up phase of the study).

Test of Primary Hypothesis

At week 16, patients in the CCBT group had a HAMD score of 8.9 (sd=5.6), with 95% confidence intervals of 7.5-10.3. Patients in the CBT group had a HAMD score of 9.2 (sd=6.3), with 95% confidence intervals of 7.6-10.8. CCBT thus met the criteria for noninferiority on the primary dependent measure. The observed between-group effect size difference was d=0.05, underscoring the equivalence of the two interventions.

Speed of Improvement and Remission

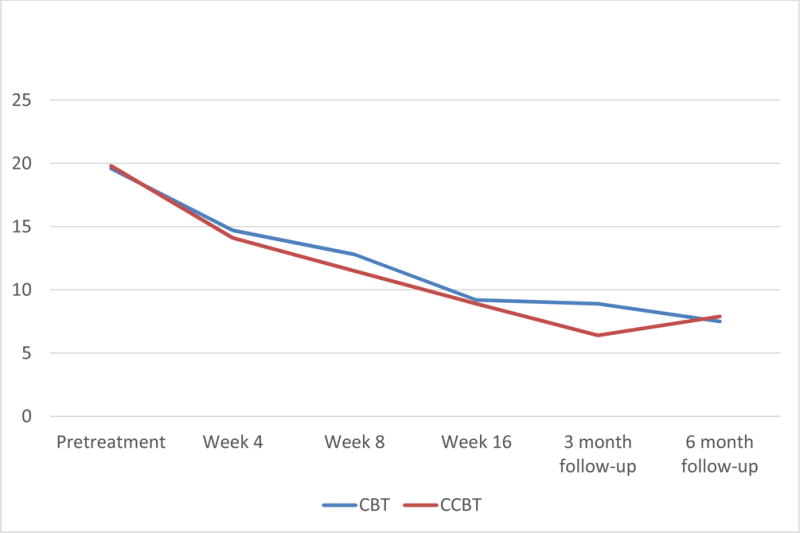

Both groups experienced large improvements across the 16 weeks of therapy: within-subject effect sizes were d=2.4 and d=2.0 for the CCBT and CBT groups, respectively. Likewise, the two treatment groups experienced a similar rate of symptom reduction across the 16 weeks of treatment (see Figure 1). For the ITT sample (n=77 per arm), remission rates were 42.9% and 41.6% for the CCBT and CBT groups, respectively. Among completers, remission rates at week 16 were 46.9% (30/64) for the CCBT group and 48.4% (30/62) for the CBT group.

Figure 1.

Treatment Outcome: Mean Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression Scores

Outcomes on Secondary Dependent Measures

Scores and 95% confidence intervals for the BDI II, IDS-SR, GAF, ATQ, DAS, IIP, and CTAS are summarized in Table 2. For the symptom and function measures, both treatment groups experienced considerable improvement, and the outcomes of the CCBT and CBT groups did not significantly differ. There was, by contrast, a significant difference on the CTAS, which indicated that patients in the CCBT group gained significantly more knowledge about the methods of cognitive-behavioral therapy than patients who received conventional CBT.

Table 2.

Means (SD) of Dependent Measures for CBT and CCBT Across Acute Phase Therapy

| Symptom severity | Pre-Treatment | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 16 | Treatment Effect* | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | CCBT | CBT | CCBT | CBT | CCBT | CBT | CCBT | |||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

|||

| 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | 19.6 (3.8) |

19.8 (3.5) |

14.7 (4.6) |

14.1 (4.7) |

12.8 (5.6) |

11.5 (4.5) |

9.2 (6.3) |

8.9 (5.6) |

F(1) = 1.86 | 0.17 |

| Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-SR | 41.1 (9.5) |

41.4 (9.6) |

28.1 (10.7) |

27.2 (9.9) |

22.6 (11.9) |

22.2 (10.3) |

16.1 (12.3) |

16.9 (11.2) |

F(1) = 0.02 | 0.89 |

| Beck Depression Inventory II | 35.1 (9.9) |

37.8 (8.3) |

21.6 (11.2) |

20.6 (9.9) |

16.1 (12.3) |

15.9 (8.7) |

11.3 (11.1) |

11.7 (9.3) |

F(1) = 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning | 56.3 (5.8) |

55.9 (6.0) |

— | — | — | — | 69.4 (9.3) |

71.4 (10.7) |

F(1) = 1.20 | 0.28 |

| Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire | 89.9 (24.6) |

88.9 (25.5) |

75.8 (26.2) |

70.1 (21.9) |

66.8 (27.6) |

63.0 (20.5) |

54.2 (26.3) |

52.1 (19.8) |

F(1) = 2.50 | 0.15 |

| Inventory of Interpersonal Problems | 91.2 (33.2) |

92.7 (31.7) |

— | — | — | — | 71.7 (38.3) |

73.9 (33.0) |

F(1) = 0.11 | 0.74 |

| Dysfunctional Attitude Scale | 144.4 (35.3) | 142.6 (35.5) | 140.2 (36.5) |

131.3 (33.9) |

132.3 (35.7) |

127.7 (31.6) |

116.3 (35.7) |

115.1 (29.3) |

F(1) = 2.02 | 0.16 |

| Cognitive Therapy Awareness Scale | 25.3 (3.9) |

24.2 (3.5) |

— | — | 28.2 (3.7) |

31.8 (4.0) |

28.3 (3.8) |

31.4 (4.0) |

F(1) = 43.4 | <.0001 |

Repeated measure analyses of variance were used. The models include treatment, time, and treatment × time interaction. The p value is for the main effect treatment. There were no assessments on week 4 for Cognitive Therapy Awareness Scale and on weeks 4 and 8 for Global Assessment of Functioning and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. Since no assessments for GAF and IIP on weeks 4 and 8, a one way ANOVA method was used.

Influence of Site, Chronicity, and Severity of Depression

The two treatments were comparably effective at the two sites, suggesting that investigator allegiance and greater familiarity with CCBT did not affect results (data available upon request). Similarly, duration of index episode was not significantly associated with outcome as main effects or as interactions with treatment group (data available upon request). Higher HAMD scores at pretreatment were associated with higher scores at week 16 (F=4.74, df=1, p=0.03), although this effect was similar for the CBT and CCBT groups (F=0.00, df=1, p=0.95).

Results at Follow-up Visits

Results at 3 and 6 months post-treatment are shown in Figure 1 and Table 3. Improvements were maintained in both groups at both follow-up visits. There were no statistically significant differences between the two treatment groups on symptom and function measures. The advantage in knowledge gained about cognitive-behavioral therapy observed in the CCBT arm was sustained across the follow-up. Among the 55 participants who were remitted at week 16 and completed the follow-up, there were only six relapses (11%). Two patients (7%) relapsed in the CBT group and 4 (16%) patients relapsed in the CCBT group (Fisher exact test, two sided, p=0.39).

Table 3.

Means (SD) of Dependent Measures for CBT and CCBT Across Six Months of Follow-up

| Symptom severity | Month 3 | Month 6 | Treatment Effect* | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | CCBT | CBT | CCBT | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Score | 8.9(6.8) | 6.4(4.5) | 7.5(6) | 7.9(5.9) | F(1) = 1.95 | 0.16 |

| Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-SR | 14.7(12.3) | 13.6(9.5) | 14.7(12.2) | 14.3(11) | F(1) = 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Beck Depression Inventory II | 10(10.6) | 8(7.8) | 9.6(10.6) | 8.6(8.1) | F(1) = 1.38 | 0.24 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning | 71.2(11.7) | 74.8(10) | 73.7(10.4) | 73.4(11) | F(1) = 1.31 | 0.25 |

| Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire | 50.5(24.3) | 46(16.9) | 49.8(23.6) | 48.7(20.9) | F(1) = 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Inventory of Interpersonal Problems | 60.5(36.7) | 66.9(31) | 57.7(37.7) | 64.2(32.6) | F(1) = 1.98 | 0.16 |

| Dysfunctional Attitude Scale | 112.7(38.3) | 111(33.2) | 107.9(34.9) | 112(33.1) | F(1) = 0.06 | 0.81 |

| Cognitive Therapy Awareness Scale | 28.4(4.4) | 31.5(4) | 28.5(4.3) | 31.6(3.4) | F(1) = 32.0 | <.0001 |

Repeated measure analyses of variance were used. The models included treatment, time, and time × treatment interaction. The p value is for the main effect treatment.

DISCUSSION

We designed this study to provide a rigorous test of a clinician-supported method of CCBT compared to standard CBT in drug-free patients with major depressive disorder. We found noninferiority the primary outcome (week 16 HAMD scores), with comparable study completion and remission rates. It is likewise noteworthy that the CCBT and CBT groups showed similar gains on other measures of depressive symptoms, negative cognitions, global functioning and interpersonal problems. The CCBT group did gain greater knowledge about cognitive-behavioral therapy compared to the CBT group, replicating the earlier finding of Wright et al.28

Although the great majority of previous trials of CCBT compared the computer-assisted delivery method with treatment as usual or a waiting list control,20–24 six prior studies of depressed patients compared CCBT with conventional CBT. The results of a recent meta-analysis of 5 of these studies suggested that comparable outcomes are possible.20 However, these studies were relatively small,28,46–50 often did not control for use of antidepressants,46–50 and used attenuated courses of individual or group therapy as the comparator.28,46–50 In the current study, we addressed these shortcomings by comparing CCBT to a full 16-week/20 session course of CBT and the primary hypothesis of equivalence was examined with a planned test of noninferiority. Moreover, we designed the study to ensure that there was a meaningful difference in the amount of clinical contact (i.e., the CBT group received 8.3 more hours of therapist contact than the CCBT group, which corresponds to 10 fewer 50 minute visits across 16 weeks). We are therefore confident that our finding of noninferiority provides strong, prospective support for the conclusion of the meta-analysis of earlier studies.

Because CCBT reduces the “dose” of therapist time, it is possible that this form of treatment would be less effective than standard CBT for patients with even greater levels of symptom severity or more complex, longstanding depressions. We also did not enroll patients who wanted to receive concomitant antidepressant therapy, which may have skewed sampling towards a subset that was more highly motivated for psychotherapy. It would be worthwhile in future research to study a wider range of depressed patients, including those who either preferred combined treatment with antidepressants or had not obtained an adequate response to pharmacotherapy.

Another limitation to the generalizability is that CCBT was conducted by well-trained therapists who demonstrated competence on the Cognitive Therapy Scale and received ongoing supervision. Therapists with similar expertise or support may not be available to assist with CCBT in some settings, and in other settings it may not be possible to provide up to 5 hours of therapist support. Further research is needed to determine if comparable outcomes can be obtained with therapists and counselors having less training or who spend less time in treatment delivery. There is some evidence from meta-analyses to suggest that therapist support times in the range of 1-3 hours may be sufficient to facilitate CCBT.20–23

A third limitation is that our study’s noninferiority design assumes that the standard of comparison, CBT, was indeed efficacious. The finding of noninferiority does not rule out the possibility that the standard therapy was ineffective and, as a result, neither treatment actually worked. To minimize the probability of this occurrence, we provided a full course of individual CBT, and the observed outcomes at both sites were comparable to those observed in controlled studies that also included antidepressants and/or pill placebo.51–53 Although we cannot rule out the possibility that CBT was no more effective than an attention-placebo condition, we are confident that study participants obtained clinically meaningful improvements that are similar to the outcomes of other studies of efficacious treatments.

Additional limitations that could be addressed in future studies include:

Independent replication of the value of this model of CCBT is still needed. It is possible that the enthusiasm of learning a new approach from the developer of the technology gave the CCBT-treated patients an advantage that could not be controlled by the research design.

It is possible that CCBT might not work as well in a less well-educated population. Other CCBT versus CBT studies that reported educational levels had similar demographic profiles,28,55–57 possibly due to increased internet availability and computer experience in such populations. Further research on CCBT is needed in settings where economically disadvantaged persons are treated, particularly with people who may have had limited previous online access or computer experience.

The study was not large enough to permit powerful analyses of potential moderators of CCBT response. We did not find significant effects for site, severity or chronicity, but It is possible that there are other, yet to be identified patient characteristics that are associated with CCBT response.

We only provided face-to-face therapist support in this investigation. Other methods of providing support (e.g., telephone, texts, e-mail)54–57 may be useful, and greater use of these methods could further reduce barriers to receiving CCBT.

The method of CCBT used in this study required use of a personal computer or tablet and is not currently available as a mobile app. We think that the learning experience is facilitated by the personal computer/tablet environment (e.g., larger screen for viewing video, keyboard for data entry, full screen display of learning exercises and checklists, and attention required to set-up and use device for concentrated period of time) as compared to the typical “on-the-go” use of mobile apps. Nevertheless, research is needed to determine if a mobile delivery method (or hybrid of personal computer/tablet plus mobile app) would improve utilization and effectiveness of this treatment approach. Two recent studies with mobile apps containing CBT oriented content found either no sustained impact on depressive symptoms58 or less robust effects59 than found in our study.

Despite these limitations, we think that further development and implementation of CCBT is warranted. With increasing utilization of computers in society, improvements in broadband speed and access, and continued work on enhancing the quality of online CCBT programs, computer-assisted methods that reduce cost and improve the efficiency of psychotherapy offer a valuable means to make treatment available to larger numbers of depressed people.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01-MH082762 (JHW) and R01-MH082794 (MET) from the National Institute of Mental Health. This study began before it was mandatory to register clinical trials. A PDF of the original statistical method and data analytic plan is available from the authors upon request to document that the study was conducted as designed and that the data analyses followed the data analysis plan.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the cognitive-behavioral therapists for this study, including the therapists from Louisville (Don Kris Small, Ph.D., Virginia Evans, L.C.S.W., Mary Hosey, L.C.S.W., Thomas “Jene” Hedden, L.C.S.W.) and Philadelphia (Elizabeth Hembree, Ph.D., Kevin Kuehlwein, Psy.D., J. Russell Ramsay, Ph.D., and Rita Ryan, Ph.D.). At the Philadelphia site, the fifth therapist was one of the authors (MET), who treated two patients during a therapist shortage. We thank Kitty de Voogd, Jordan Coella, Christine Johnson and Carol Wahl for their assistance. Andrew S. Wright, M.D., and Aaron Beck, M.D. coauthored the prototype for the GDA program with one of the authors (JHW) of this paper. Eve Phillips, M.B.A., provided support for the GDA software.

Dr. Wright is the lead author of the Good Days Ahead (GDA) program used in this investigation and has an equity interest in Empower Interactive and Mindstreet, developers and distributors of GDA. He receives no royalties or other payments from sales of this program. His conflict of interest is managed with an agreement with the University of Louisville. He receives book royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Guilford Press, and Simon and Schuster. None of the other authors (Drs. Thase, Eells, Barrett, Wisniewski, Balasubramani, McCrone and Brown) have disclosures or potential conflicts of interest pertaining to the Good Days Ahead program. The Universities of Pennsylvania, Louisville, Pittsburgh, and King’s College London similarly have no financial relationships with Empower Interactive or Mindstreet.

Dr. Thase reports the following other relationships during the course of this study. He was an advisory/consultant to Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan (Forest, Naurex), AstraZeneca, Cerecor, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson (Janssen, Ortho-McNeil), Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Mocksha8, Nestlé (PamLab), Neuronetics, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, Sunovion, and Takeda. In addition to the National Institute of Mental Health, he received grant support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Alkermes, Assurex, Avanir, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda. Dr. Thase received royalties from the American Psychiatric Press, Guilford Publications, Herald House and W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Dr. Thase’s spouse, Dr. Diane Sloan, works for Peloton Advantage, which did business with Pfizer and AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Disclosures

No of the other authors report disclosures or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Third. Arlington, VA: Available at http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=24158. Accessed November 27, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parikh SV, Quilty LC, Ravitz P, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 2. Psychological Treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):524–539. doi: 10.1177/0706743716659418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(7):376–385. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, van Oppen P, Andersson G. Are psychological and pharmacologic interventions equally effective in the treatment of adult depressive disorders? A meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1675–1685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitz ES, Hollon SD, Twisk J, et al. Baseline Depression Severity as Moderator of Depression Outcomes Between Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs Pharmacotherapy: An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(11):1102–1109. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, Jarrett RB. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(3):475–488. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biesheuvel-Leliefeld KE, Kok GD, Bockting CL, et al. Effectiveness of psychological interventions in preventing recurrence of depressive disorder: meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, Andersson G, Beekman AT, Reynolds CF., III Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):56–67. doi: 10.1002/wps.20089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karyotaki E, Smit Y, Holdt Henningsen K, et al. Combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy or monotherapy for major depression? A meta-analysis on the long-term effects. J Affect Disord. 2016;194:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Fawcett J, et al. Effect of cognitive therapy with antidepressant medications vs antidepressants alone on the rate of recovery in major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(10):1157–1164. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: results of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):375–384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaltenthaler E, Sutcliffe P, Parry G, Beverley C, Rees A, Ferriter M. The acceptability to patients of computerized cognitive behaviour therapy for depression: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38(11):1521–1530. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus SC, Olfson National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eells TD, Barrett MS, Wright JH, Thase ME. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy for depression. Psychotherapy. 2014;51(2):191–197. doi: 10.1037/a0032406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griest JH. Computer interviews for depression management. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 16):20–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright JH, Wright A. Computer assisted psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res. 1997;6(4):315–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beating the Blues™ US – Helping you to manage your emotional well-being. http://beatingthebluesus.com/ Accessed November 27, 2016.

- 18.MoodGYM training program. https://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome Accessed November 27, 2016.

- 19.Empower interactive. Good Days Ahead. http://www.empower-interactive.com/solutions/good-days-ahead/ Accessed November 27, 2016.

- 20.Andersson G, Topooco N, Havik O, Nordgreen T. Internet-supported versus face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(1):55–60. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1125783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards D, Richardson T. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnberg FK, Linton SJ, Hultcrantz M, Heintz E, Jonsson U. Internet-delivered psychological treatments for mood and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of their efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So M, Yamaguchi S, Hashimoto S, et al. Is computerized CBT really helpful for adult depression? A meta-analytic re-evaluation of CCBT for adult depression in terms of clinical implementation and methodological validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozental A, Magnusson K, Boettcher J, Andersson G, Carlbring P. For better or worse: an individual patient data meta-analysis of deterioration among participants receiving internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000158. Epub ahead of print 10.1037/ccp0000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbody S, Littlewood E, Hewitt C, et al. Computerised cognitive behavior therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h5627. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright JH, Wright AS, Salmon P, et al. Development and initial testing of a multimedia program for computer-assisted cognitive therapy. Am J Psychother. 2002;56(1):76–86. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DR, Hantsoo L, Thase ME, Sammel M, Epperson CN. Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for pregnant women with major depressive disorder. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23(10):842–848. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano AM, et al. Computer-assisted cognitive therapy for depression: maintaining efficacy while reducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1158–1164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2015. (Research Version, Patient/Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/P w/PSY SCREEN)). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thase ME, Simons AD, Cahalane J, McGeary J, Harden T. Severity of depression and response to cognitive behavior therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):784–789. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.6.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thase ME, Reynolds CF, III, Frank E, et al. Response to cognitive behavior therapy in chronic depression. J Psychother Pract Res. 1994;3:204–214. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallis TM, Shaw BF, Dobson KS. The Cognitive Therapy Scale: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(3):381–385. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck J Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME. Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollon SD, Kendall PC. Cognitive self-statements in depression: development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cogn Ther Res. 1980;4:383–395. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissman AN. Doctoral dissertation. University of Pennsylvania; 1979. The Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale: a validation study Dissertation Abstracts International, 40, 1389B–1390B. 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS. Inventory of Interpersonal Problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):885–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thase ME, Larsen KG, Kennedy SH. Assessing the ‘true’ effect of active antidepressant therapy v. placebo in major depressive disorder: use of a mixture model. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:501–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Second. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, Sorrell SP, Erdman HP. Computer-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(1):51–56. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spek V, Nyklícek I, Smits N, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold depression in people over 50 years old: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychol Med. 2007 Dec;37(12):1797–806. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kay–Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Kelly B, Lewin TJ. Clinician-assisted computerized versus therapist-delivered treatment for depressive and addictive disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 2011;195(3):S44–50. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner B, Horn AB, Maercker A. Internet-based versus face-to-face cognitive-behavioral intervention for depression: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. J Affect Disord. 2013;152–154:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersson G, Hesser H, Veilord A, Svedling L, Andersson F, Sleman O, Mauritzson L, Sarkohi A, Claesson E, Zetterqvist V, Lamminen M, Eriksson T, Carlbring P. Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial with 3-year follow-up of internet-delivered versus face-to-face group cognitive behavioural therapy for depression. J Affect Disord. 2013 Dec;151(3):986–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Evans MD, et al. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Singly and in combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):774–781. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100018004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(8):658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohr DC, Duffecy J, Ho J, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a manualized telecoaching protocol for improving adherence to a web-based intervention for the treatment of depression. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoifodt RS, Lillevoll KR, Griffiths KM, et al. The clinical effectiveness of web-based cognitive behavioral therapy with face-to-face therapist support for depressed primary care patients: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e153. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hallgren M, Kraepelien M, Ojehagen A, et al. Physical exercise and internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy in the treatment of depression: randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(3):227–234. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Lehr D, et al. Effect of a web-based guided self-help intervention for prevention of major depression in adults with subthreshold depression – a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1854–1863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Birney AJ, Gunn R, Russell JK, Ary DV. MoodHacker mobile web app with email for adults to self-manage mild-to-moderate depression: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roepke AM, Jaffee SR, Riffle OM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of SuperBetter, a smartphone-based/internet-based self-help tool to reduce depressive symptoms. Games Health J. 2015;4(3):235–246. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2014.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.