Abstract

Background

Plasmodium falciparum delayed clearance with the use of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACTs) has been reported in some African countries. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in two genes, P. falciparum adaptor protein complex 2 mu subunit (pfap2mu) and ubiquitin specific protease 1 (pfubp1), have been linked to delayed clearance with ACT use in Kenya and recurrent imported malaria in Britain. With over 12 years of ACT use in Ghana, this study investigated the prevalence of SNPs in the pfap2mu and pfubp1 in Ghanaian clinical P. falciparum isolates to provide baseline data for antimalarial drug resistance surveillance in the country.

Methods

Filter paper blood blots collected in 2015–2016 from children aged below 9 years presenting with uncomplicated malaria at hospitals in three sentinel sites Begoro, Cape Coast and Navrongo were used. Parasite DNA was extracted from 120 samples followed by nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR). Sanger sequencing was performed to detect and identify SNPs in pfap2mu and pfubp1 genes.

Results

In all, 11.1% (9/81) of the isolates carried the wildtype genotypes for both genes. A total of 164 pfap2mu mutations were detected in 67 isolates whilst 271 pfubp1 mutations were observed in 72 isolates. The majority of the mutations were non-synonymous (NS): 78% (128/164) for pfap2mu and 92.3% (250/271) for pfubp1. Five unique samples had a total of 215 pfap2mu SNPs, ranging between 15 and 63 SNPs per sample. Genotypes reportedly associated with ART resistance detected in this study included pfap2mu S160N (7.4%, 6/81) and pfubp1 E1528D (7.4%, 6/81) as well as D1525E (4.9%, 4/81). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of the SNPs between the three ecologically distinct study sites (pfap2mu: χ2 = 6.905, df = 2, P = 0.546; pfubp1: χ2 = 4.883, df = 2, P = 0.769).

Conclusions

The detection of pfap2mu and pfubp1 genotypes associated with ACT delayed parasite clearance is evidence of gradual nascent emergence of resistance in Ghana. The results will serve as baseline data for surveillance and the selection of the genotypes with drug pressure over time. The pfap2mu S160N, pfubp1 E1528D and D1525E must be monitored in Ghanaian isolates in ACT susceptibility studies, especially when cure rates of ACTs, particularly AL, is less than 100%.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-018-2762-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Antimalarial drug resistance, Artemisinin, ACT, pfubp1, pfap2mu, Mutations, Ghana

Background

Malaria is still a debilitating disease, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA) where there were 212 million cases and 429,000 malaria-related deaths in 2015 [1]. There has been a 21 and 29% reduction in morbidity and mortality, respectively, since 2010, probably as a result of the implementation of integrated control strategies [1, 2]. The control efforts employed included the use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), chemoprevention in pregnant women and children as well as chemotherapy with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). As such, the development of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to artemisinin (ART) derivatives as reported from Southeast Asia (SEA) is quite worrying [1]. Chemotherapy, which is one of the core control strategies for the disease, has been hindered over the years by the emergence and spread of parasites resistant to the commonly used antimalarial drugs [1]. Currently, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has initiated the containment of drug resistance in the SEA region with the deployment of a multi-sector strategy [1]. Although this initiative is commendable, the need for country-level monitoring of the genome of parasite populations for possible evolution and selection due to drug pressure is also crucial for the early detection of emerging drug resistance.

For over a decade, molecular markers of antimalarial drug resistance have been used to monitor the emergence and spread of drug resistance in malaria endemic areas. These genetic markers are mainly single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes encoding drug target proteins in essential biochemical pathways of the parasite. The levels of drug susceptibility in the parasites have been linked to SNPs or haplotypes of the genes, and these markers are relevant in antimalarial drug efficacy studies. The recent observation of parasite resistance to ART in SEA set into motion the need to discover a molecular marker for surveillance of drug susceptibility. Ariey et al. [3] discovered the SNPs in the kelch propeller domain on chromosome 13 of the P. falciparum genome known as k13 in drug resistance isolates in vitro. Three of the k13 polymorphisms, C580Y, R538T and Y493H were also present in slow clearing clinical isolates with ART use. The presence of the SNPs showed varying parasite clearance half-life in patients; however, the C580Y mutation was linked to longest parasite clearance half-life compared to the other SNPs. So far these SNPs have not been detected in African isolates [4–6] and the quest for novel markers for ART resistance is ongoing. Henriques et al. [7] linked SNPs in two genes, the P. falciparum adaptor protein complex 2 mu subunit (pfap2mu) and ubiquitin-specific protease 1 (pfubp1) to delayed clearance of parasites. The pfap2mu gene mutation was at codon 160 resulting in the amino acid change from serine to either asparagine or threonine (S160N/T). The pfubp1 gene mutations were at codon 1525, a change from aspartic acid to glutamic acid (D1525E) and codon 1528 from glutamic acid to aspartic acid (E1528D) in the Kenyan isolates. In addition, Sutherland et al. [8] reported four UK residents with imported malaria who showed recurrent malaria after AL treatment [8]. These mutations, pfap2mu S160N and pfubp1 E1525D/Q were observed in the recurrent parasites but none of the known K-13 gene mutations were observed [8]. Although the role played by both genes in artemisinin action is not clearly understood, the ap2mu gene is known to encode the μ- subunit of the adaptor protein 2 complex (AP2) involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis into the parasite vacuole [9]; ubp1 encodes a deubiquitinating (DUB) enzyme that functions by cleaving ubiquitin from any protein or peptide to which it is joined [10]. The polymorphic homologues of these two P. falciparum genes were first identified in the rodent malaria parasite, P. chabaudi (pcubp1 encodes ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase 1) and pcap2mu encodes clathrin vesicle-associated adaptor 2 mu subunit), as being associated with ART resistance [11]. More studies are therefore needed to validate these polymorphisms and their role in antimalarial drug resistance.

The use of ACTs in Ghana began in 2005 and since then the cure rate of the drugs in use, artesunate-amodiaquine (AS-AQ) and artemether-lumifantrine (AL), has been 100 and 97.6%, respectively, as of 2014 [12]. Surveillance studies using the P. falciparum multidrug resistance gene (pfmdr1) SNPs (haplotype N86-F184-D1246) linked to reduced parasite susceptibility to AL showed an increasing trend over the years in Ghana from 2005 to 2010 [13]. In addition, increased pfmdr1 gene copy number linked to parasite reduced susceptibility to artesunate (AS), mefloquine (MQ), halofantrine and AL [14–16] were also detected in Ghanaian isolates [13]. The findings from the reported studies above are indicative of a subtle emergence of parasite resistance to ART and to ACTs especially AL in Ghana. Therefore, the monitoring of newly discovered molecular markers is essential as an early warning signal to the emergence of resistance in Ghana. This study determined the prevalence of known and novel SNPs in the pfubp1 and pfap2mu in Ghanaian isolates collected from three ecologically distinct areas for monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy in Ghana to serve as baseline data for antimalarial drug resistance surveillance in Ghana.

Methods

Study sites

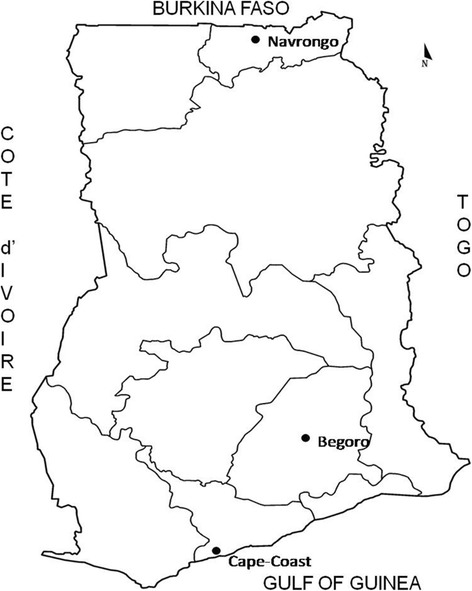

The Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) in collaboration with the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) have set up ten sentinel sites in the ten regions of Ghana for monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy. These sites lie in the three distinct ecological zones in the country. Of the ten sites, samples from three sites were used for this study. The sites include Navrongo (10°53'44.05"N, 1°05'31.56"W) located in the Kassena Nankana District in the Upper East Region and lies in the guinea savannah zone; Begoro (6°23'29.76"N, 0°22' 46.20"W) located in the Fanteakwa District of the Eastern Region lies in the forest zone; Cape Coast (5°06'00”N, 1°15'00"W), the capital town of Central Region lies in the coastal savannah zone (Fig. 1). The forest and coastal savannah zones experience perennial malarial transmission whilst the guinea savannah zone experiences a seasonal malaria transmission pattern with almost all cases occurring during rainy months between May-June and October-November of each year.

Fig. 1.

The map of Ghana showing the three study sites, Navrongo, Begoro and Cape Coast in three different ecological areas, guinea savannah, forest and coastal savanna

Study samples

Filter paper blood blots collected in 2015–2016 from children aged below 9 years with uncomplicated malaria reporting at designated health care facilities in Navrongo, Begoro and Cape Coast were used for the study. In total 120 samples (40 from each site) were used for this investigation.

Detection of pfubp1 and pfap2mu gene polymorphisms

Parasite DNA was extracted from 120 pre-treatment blood blot samples on filter paper (WhatmanTM 3 Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) using the QIAmp DNA mini kit (Qiagen GmBH, Hilden, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. This was followed by amplification of the pfap2mu and pfubp1 genes using nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) following a previously published protocol [7] with minor modifications. The PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl with the following reaction mixture: 0.2 μM of each primer (Table 1), 4.0 mM MgCl2, 0.4 μM deoxynucleotides triphosphate (dNTPs), 1 U One-Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, Massachusetts, USA), 1× PCR buffer, nuclease free water and 2 μl of the extracted parasite DNA. One microlitre of the first round product was used as a template in a 50 μl inner PCR reaction. A DNA sample extracted from the 3D7 parasite strain was used as a positive control. The PCR thermal conditions were the same for both genes but different annealing temperatures as shown in Table 1. The thermal cycle programme for each 1st amplification was 94 °C for 3 min, and 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, annealing temperature for 30 s and 68 °C for 1 min with a final extension of 68 °C for 15 min. The second round of PCR consisted of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, annealing temperature for 30 s and 68 °C for 45 s with a final extension of 68 °C for 10 min. The PCR amplicons for the fragments of the two genes were sequenced using Sanger sequencing.

Table 1.

Primer sequences, sizes of PCR amplicons and annealing temperature of the amplification of pfap2mu and pfubp1 genes

| Gene | Primers (5'–3') | Size of PCR amplicon (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pfap2mu | Primary amplification | 2247 | 50 |

| Forward: AAGACTGTCAAATGTAAAAGACCC | |||

| Reverse: CTCATGTAAAACAAAAAGTGAGG | |||

| Secondary amplification | 841 | 52 | |

| Forward: GATATCCACAAACATTAGAAGTG | |||

| Reverse: CCATCTGGTGGTGTGAAGG | |||

| pfubp1 | Primary amplification | 484 | 52 |

| Forward: CGCCCGTACTATGAAGAAGATC | |||

| Reverse: GGCTTTTACCTGAACTGTTCAGG | |||

| Secondary amplification | 304 | 57 | |

| Forward: CGTAAACAGAATATTCAGGATTGC | |||

| Reverse: CTAGCCCTTTATTATCATTATCG |

Data analysis

The sequence data of the isolates were analysed using the CLC Genomics Workbench 10.01 software (Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark) and Benchling.com (California, CA, USA). PF3D7_1218300 and PF3D7_0104300 (PlasmoDB) were used as reference sequences to detect SNPs in the pfap2mu and pfubp1 respectively. Poor quality sequences of isolates after three sequencing trials were not analysed. The prevalence of individual SNPs was determined for each site. Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportions of mutations occurring in the three sites and to determine any significant differences in the prevalence of the mutations among the three sites using the GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a P-value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Polymorphisms in pfap2mu and pfubp1

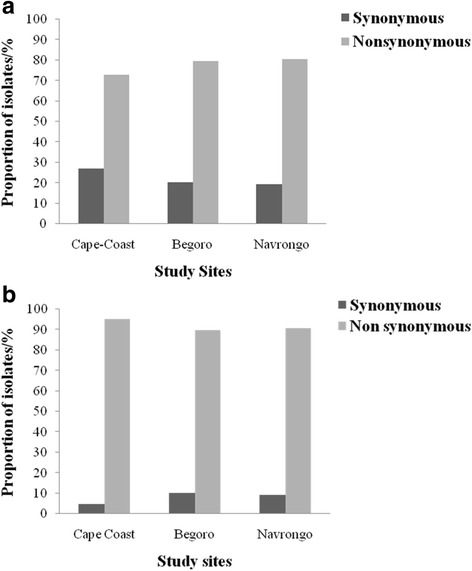

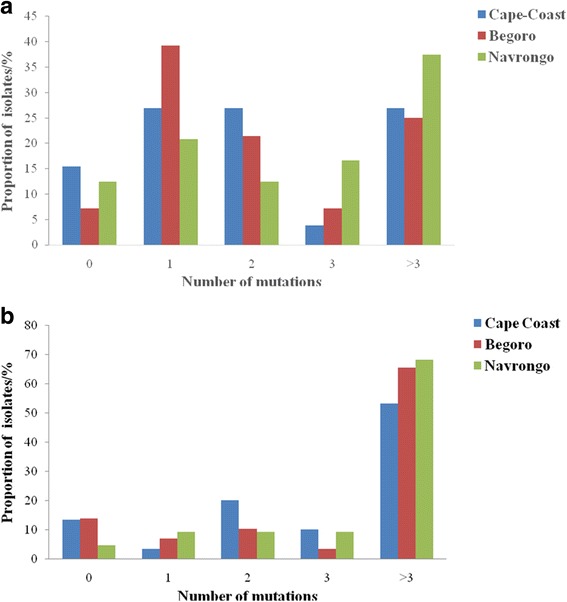

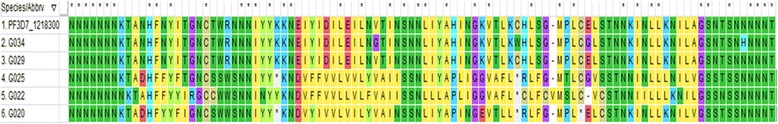

For the pfap2mu gene, 96 samples were sequenced and 15 were of low quality as determined by quality assurance analysis. Of the 81 good sequences, 35% (28/81), 35% (28/81) and 31% (25/81) were from Cape-Coast, Begoro and Navrongo, respectively. The proportion of isolates with no mutations in the pfap2mu gene, that is wildtype sequence as the 3D7 strain, was 11.1% (9/81). The sequence analysis revealed several SNPs and the total number observed in 67 samples (of the 72 with mutations) was 164 SNPs with ≤ 5 mutations per sample. Of the 164 SNPs, 78.0% (128/164) were non-synonymous (NS) and 22.0% (36/164) were synonymous (SYN) mutations. The distribution of pfap2mu NS and SYN mutations in isolates from the three sites is shown in Fig. 2a. There was no significant difference in the type of mutation (SYN or NS) present between the three sites (χ2 = 1.960, df = 2, P = 0.360). The distribution of the single or multiple mutations for each site is shown in Fig. 3a. About 68.6% (46/67) of the isolates with mutations had more than one mutation and 36% (9/25) of the isolates from Navrongo had more than three mutations per isolate. In addition, there were insertions and deletions in some of the isolates from the three sites. In all 22 common SNPs were detected in either two of the three sites or all three sites. These include Q149R, S160N, V161K, V161E, D168E, R188R, D203F, D203Y, E206*, T235T, N240Y, N240F, K256*, D263V, V270V, I272I, G284G, K285E, T302T, N317S, T318T and T325T. Nine of these SNPs were shared in all three sites and the proportion of isolates from the study sites is shown in Fig. 4a. Of these SNPs, three NS mutations were present in isolates from the three sites: S160N, D168E and V161K. The nucleotide changes for the SNPs are shown in Table 2. The amino acid sequences alignment for 21 isolates are shown in Fig. 5. There were 5 other isolates (of the 72 with mutations) with a total of 215 pfap2mu SNPs (G020, 63 SNPs; G022, 60 SNPs; G025, 47 SNPs; G029, 30 SNPs; G034, 15 SNPs) and were all from Begoro. The amino acid sequences for these 5 isolates are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of pfap2mu and pfubp1 NS and SYN mutations in isolates from the three sites. a pfap2mu. b pfubp1

Fig. 3.

Proportion of isolates from the three sites with varying number of pfap2mu and pfubp1 mutations. a pfap2mu. b pfubp1

Fig. 4.

Proportion of isolates from the three sites with shared pfap2mu and pfubp1 mutations. a pfap2mu. b pfubp1

Table 2.

Shared pfap2mu mutations observed in the isolates from the three sites. Mutations indicated in bold are known delayed clearance genotypes, underlined nucleotides are the changed bases

| Nucleotide position | Nucleotide change | Amino acid position and change |

|---|---|---|

| 446 | CAG to CGG | Q149R |

| 479 | AGT to AAT | S160N |

| 481 | GTG to AAG | V161K |

| 482 | GTG to GAG | V161E |

| 504 | GAT to GAA | D168E |

| 564 | AGA to AGG | R188R |

| 607 | GAT to TAT | D203Y |

| 607, 608 | GAT to TTT | D203F |

| 616 | GAA to TAA | E206a |

| 705 | ACA to ACG | T235T |

| 718 | AAT to TAT | N240Y |

| 767 | AAG to TAG | K256a |

| 789 | GAT to GTT | D263V |

| 810 | GTA to GTT | V270V |

| 852 | GGA to GGG | G284G |

| 855 | AAG to GAG | K285E |

| 951 | AAC to AGC | N317S |

| 954 | ACA to ACC | T318T |

aStop codon

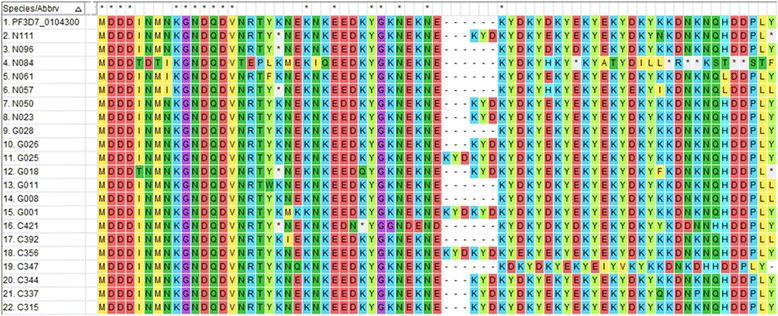

Fig. 5.

A sequence alignment of pfap2mu gene showing amino acid changes due to single nucleotide polymorphisms. The alignment was done using pfap2mu reference sequence of the 3D7 strain (PF3D7_1218300). Mutations present at codons 185–282, nucleotide positions 553–849 of pfap2mu for 21 samples. Samples C314 and G026 had a frameshift, samples C312. C314, C315, C408, G009, G011, G012, G033, N030 and N102 had an asparagine (N) insertion at codon 233, as well as a lysine (K) insertion at the same position for sample N055

Fig. 6.

A sequence alignment for 5 samples with multiple mutations. The alignment was done using pfap2mu reference sequence of the 3D7 strain (PF3D7_1218300). About 215 SNPs were observed in these isolates ranging from 15 to 63 SNPs per isolate. These mutations were found from codons 227–324, nucleotide positions 679–970 and are likely due to multiplicity of infection

For the pfubp1 gene, 81 quality sequence data were analysed comprising 37% (30/81), 35.8% (29/81) and 27.2% (22/81) from Cape Coast, Begoro and Navrongo, respectively. About 11.1% (9/81) of the isolates had no mutations in their pfubp1 gene. A total of 271 SNPs were observed in the 72 sequences of which 92.3% (250/271) were NS and 7.7% (21/271) were SYN mutations. The proportion of isolates with either pfubp1 NS or SYN mutations for each site is shown in Fig. 2b. The proportion of isolates with varying number of mutations is also shown in Fig. 3b for the three study sites. Overall, 93.1% (67/72) of the isolates with mutations had more than one pfubp1 SNP. The majority of isolates from Begoro (65.5%, 19/29) had more than 3 mutations per isolate for the pfubp1 gene. There were 15 common SNPs detected in isolates from all three sites. These include D1539D, E1528D, I1487I, I1552M, K1502*, K1537L, N1542D, N1551G, N1560I, N1560K, P1547P, Q1543H, Y1501F, Y1549* and Y1549L. The proportion of isolates with these mutations from each of the study sites is shown in Fig. 4b. There were 36 other shared SNPs detected in isolates from two out of the three sites. The nucleotide changes for the commonly shared mutations are also shown in Table 3. The amino acid sequence alignment is shown in Fig. 7.

Table 3.

Shared pfubp1 mutations observed in the isolates from the three sites. Mutations indicated in bold are known delayed clearance genotypes

| Nucleotide position | Nucleotide change | Amino acid position and change |

|---|---|---|

| 4383 | CCT to ACC | P1461T |

| 4386 | TAT to TTA | Y1462L |

| 4389 | CGT to TCG | R1463S |

| 4392 | AAA to TAA | K1464a |

| 4461 | ATA to ATC | I1487I |

| 4461 | ATA to ACC | I1487T |

| 4466 | ATG to ACG | M1489T |

| 4502 | TAT to TTT | Y1501F |

| 4504 | AAA to TAA | K1502a |

| 4509 | AAT to ATT | N1503I |

| 4509 | AAT to ATG | N1503M |

| 4527 | GAA to GAC | E1509D |

| 4554 | AAC to TAT | N1518Y |

| 4557 | GAA to GAC | E1519D |

| 4561 | TAT to AAT | Y1521N |

| 4575 | GAC to GAA | D1525E |

| 4581 | TAT to TTT | Y1527F |

| 4581 | TAT to AAT | Y1527N |

| 4584 | GAA to GAC | E1528D |

| 4599 | TAT to TAC | Y1533Y |

| 4602 | GAT to GAA | D1534E |

| 4608 | TAC to TCC | Y1536S |

| 4611 | AAA to TTT | K1537F |

| 4609 | AAA to TTA | K1537L |

| 4611 | AAA to TAC | K1537Y |

| 4617 | GAT to GAC | D1539D |

| 4623 | AAA to CTT | K1541L |

| 4623 | AAA to AAT | K1541N |

| 4626 | AAT to GAT | N1542D |

| 4629 | CAA to CAT | Q1543H |

| 4632 | CAT to CTT | H1544L |

| 4632 | CAT to CCT | H1544P |

| 4632 | AAA to AAT | K1544N |

| 4641 | CCA to CCT | P1547P |

| 4647 | TAT to TAG | Y1549a |

| 4647 | TAT to TTT | Y1549F |

| 4646 | TAT to TTG | Y1549L |

| 4650 | GAT to ATT | D1550I |

| 4650 | GAT to AAT | D1550N |

| 4651 | AAT to GGT | N1551G |

| 4653 | AAT to ATT | N1551I |

| 4653 | AAT to CTT | N1551L |

| 4656 | ATT to ATG | I1552M |

| 4659 | AAT to AAC | N1553N |

| 4667 | TAC to TGC | Y1556C |

| 4674 | AAT to GAT | N1558D |

| 4679 | AAT to ATA | N1560I |

| 4680 | AAT to AAA | N1560K |

| 4683 | AAA to AAG | K1561K |

| 4692 | GAG to GAC | E1564D |

| 4695 | TTC to GGC | F1565G |

| 4694 | TTC to CAA | F1565Q |

| 4765 | AAA to TAA | K1589a |

aStop codon

Fig. 7.

A sequence alignment of pfubp1 gene showing amino acid changes due to single nucleotide polymorphisms. The alignment was done using pfubp1 reference sequence of the 3D7 strain (PF3D7_0104300). Mutations from codons 1483–1549 at nucleotide positions 4449–4647 is shown. The gaps are a result of the insertions of amino acids which resulted in a frameshift. The gap between 1519E and 1520K are therefore a result of a 6 amino acid insertion in C356, G001 and G025. The known mutations D1525E and E1528D are shown in the isolates N061 and N096 respectively. A frameshift mutation is observed in N084, after codon 1536 as a result of a deletion

Two samples, G005 and C329, had wildtype sequences for both pfap2mu and pfubp1. Of the 5 isolates with many pfap2mu SNPs, 2 were wildtype for pfubp1 (G022 and G034). For the other three, G020 had 4 SNPs, G025 had 2 SNPs and G029 had 11 SNPs for the pfubp1.

Prevalence of pfap2mu and pfubp1 SNPs from the three sentinel sites

The pfap2mu SNPs were detected in 92.9% (26/28), 85.7% (24/28) and 88% (22/25) from Begoro, Cape Coast and Navrongo respectively. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of pfap2mu SNPs in the isolates from the three sites (χ2 = 6.905, df = 2, P = 0.546). The most prevalent mutation was R188R and was observed in 25.9% (21/81) of the isolates. The D168E was also observed in 22.2% (18/81) of the isolates. S160N which have been reported to be associated with ACT delayed clearance was prevalent in 7.4% (6/81) of the isolates whilst the V161K was seen in 6.2% (5/81). The S160N genotypes occurred mostly in isolates from Cape Coast (24.7%) as compared to the other two sites. In all, 35 indels were identified with 17.1% (6/35) causing a frame shift in the sequence reading frame (Fig. 5).

For pfubp1, mutations were detected in 86.7% (26/30) of the Cape Coast isolates, 86.2% (25/29) for Begoro and 95.5% (21/22) for Navrongo. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of SNPs in the isolates from the three sites (χ2 = 4.883, df = 2, P = 0.769). The most prevalent NS mutation was K1502* which was observed in 18.5% (15/81) of the isolates. The reported SNPs linked to delayed clearance of parasite with ACT use, E1528D and D1525E, were observed in 7.4% (6/81) and 4.9% (4/81) of the isolates, respectively. The predominant SYN mutation I1487I was observed in 11.1% (9/81) of the isolates. In all, 20 indels were identified with 25% (5/20) causing a frame shift in the sequence reading frame (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genetic insertions in the pfubp1 gene of isolates from the study sites

| Sample ID | Amino acids | Insertion | Nucleotide position |

|---|---|---|---|

| C315 | KYE | AAA TAT GAA | 4576 to 4584 |

| C337 | KYE | AAA TAT GAA | 4583 to 4591 |

| C344 | KYE | AAA TAT GAA | 4548 to 4556 |

| C356 | KYEKYE | AAA TAT GAA AAA TAT GAA | 4588 to 4605 |

| C360 | KYE | AAA TAT GAA | 4583 to 4591 |

| C321 | EKY | GAA AAA TAT | 4590 to 4598 |

| G001 | DKYDKY | GAC AAA TAT GAC AAA TAT | 4563 to 4580 |

| G018 | EKY | GAA AAA TAT | 4598 to 4606 |

| G025 | KYDKYE | AAA TAT GAC AAA TAT GAA | 4585 to 4602 |

| G026 | EKY | GAA AAA TAT | 4580 to 4588 |

| G034 | YDKYDK | TAT GAC AAA TAT GAC AAA | 4579 to 4596 |

| N023 | EKY | GAA AAA TAT | 4582 to 4590 |

| N031 | EKY | GAA AAA TAT | 4582 to 4590 |

| N050 | KNE | AAA AAC GAA | 4549 to 4557 |

| N111 | YEK | TAT GAA AAA | 4597 to 4605 |

The results showed a number of SNPs that were being inherited together on the gene as haplotypes in some of the isolates. However, the prevalence of the haplotypes was low (Table 5). Twenty-two different haplotypes were observed: 3 for pfap2mu and 19 for pfubp1. The most prevalent haplotype for the pfap2mu gene was V161K-D168E, which was observed in 8.6% (7/81) of the isolates with mutations. For the pfubp1 gene, the haplotypes Y1548L-N1560I, Y1549L-I1552M and N1560I-L1563 were each observed in 3.7% (3/81) of the isolates. Most of the haplotypes for both genes were observed in isolates from Begoro.

Table 5.

Haplotypes of the pfap2mu and pfubp1 mutations in Ghanaian isolates

| Gene | Haplotype | No. of isolates |

|---|---|---|

| pfap2mu | V161K-D168E | 7 |

| V161E-R188R | 6 | |

| D168E-R188R | 6 | |

| pfubp1 | I1487I-N1488D | 2 |

| I1487I-N1490I | 2 | |

| Y1549L-I1552M | 3 | |

| N1540H-K1541N | 2 | |

| N1540H-H1544P | 3 | |

| N1540H-N1542D | 2 | |

| N1488D-D1525H | 2 | |

| I1487I-Y1501F | 2 | |

| N1490I-Y1501F | 2 | |

| N1560I-L1563A | 3 | |

| E1528D-N1560K | 2 | |

| Y1549L-N1560I | 3 | |

| Y1549L-I1552M | 2 | |

| Y1501W-Y1549L | 2 | |

| N1542D-Q1543H | 2 | |

| N1488D-G1492G | 2 | |

| Q1543H-P1547P | 2 | |

| I1487I-N1490I-H1544L | 2 | |

| N1490I-Y1501F-Y1533Y-P1547P-K1554N-N1555I-D1557N | 2 |

Discussion

The search for a molecular marker for the early detection of ART resistance by the malaria parasite is ongoing. The use of molecular markers to track and identify early development of parasite resistance to drugs is a powerful tool that should be available in all malarious regions of the world. With the implementation of ACTs in Africa, studies to identify possible markers of resistance have not been conducted extensively in the continent. The key k13 molecular marker, which has been linked to drug resistance in SEA has not been observed in African isolates, partly because there is no ‘true resistance’ to ARTs except delayed clearance of parasites. New markers that have recently been discovered, such as the pfap2mu and pfubp1 gene mutations [7], need further validation for their role in delayed parasite clearance. This study detected ART delayed clearance associated polymorphisms of the pfap2mu and pfubp1 genes in Ghanaian isolates from three sites located in three distinct ecological zones. Majority of the isolates had mutations of both genes and were mostly NS mutations. The known delayed clearance genotypes, pfap2mu N160 and pfubp1 D1528 and E1525, were observed in 7.4, 7.4 and 4.9% of the isolates, respectively. It is interesting to note that although these were not the predominant mutations, it is an indication of the presence of these drug resistance genotypes in Ghanaian parasite populations and in the long term their selection with drug use will enhance the emergence of ART resistance in Ghana.

The observation that minority of the isolates were wildtype with no mutations like the reference 3D7 strain (11.1% for both pfap2mu and pfubp1) is indicative of the high rate of spontaneous mutations in the two genes. For pfap2mu, a study by Henriques et al. [7] reported that 41.5% of Kenyan isolates had wildtype gene sequence whilst another study reported 92.8% and 30.9% for Ethiopian and Tanzanian isolates, respectively [17]. Comparatively, the Ghanaian isolates had low levels of wildtype strains portraying a rapid genetic recombination of different parasite clones (multiclonal infections observed in Ghana) during the sexual stage in the vector resulting in gene shuffling [18]. About 64% and 93% of the isolates, respectively, had more than one mutation for the pfap2mu and pfubp1 genes.

The results revealed a high proportion of NS mutations, 78% and 92% for pfap2mu and pfubp1, respectively, in the Ghanaian isolates. The NS mutations are of much importance because each amino acid substitution may affect protein conformation and function [19]. Most of the NS mutations were single base or double base substitutions. For SYN mutations, it was initially assumed that since the resultant change of the nucleotide does not affect the amino acid, the change may go undetected as the gene function may not necessarily be affected [20]. However, this perception has since changed due to the evidence that SYN mutations in the pfmdr1 gene resulted in alterations in the functions of the P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a product which affects drug interactions [21]. A high prevalence of novel ap2mu mutation, D168E (25%), was observed in the Ghanaian isolates from all three sites followed by V161K (7%). The codons for the common mutations found among the isolates from all the three sites were between codons 160 and 170. The known SNP, pfap2mu S160N, found in Kenyan isolates with delayed clearance [7] was also found in all three sites (7.2%). In addition, isolates from a UK patient who arrived from Angola and failed AL treatment had the S160N thereby strengthening the role of that mutation in recurrent parasitemia with AL use [8]. The observed pfubp1 E1528D in Ghanaian samples was also seen in Kenyan and Tanzanian isolates [7, 17]. Borrmann et al. [22] first identified this mutation in Kenyan isolates. The prevalence of E1528D in Ghanaian isolates was 7.4%, which is lower than that of Kenya’s 17.1% but higher than that of Tanzania (4.8%) [7, 17]. However, with the continuing use of ACTs, the mutation may be selected and the prevalence may increase with time as observed in Kenya. The SYN mutation N1518 found in the Kenyan and Burkinabe isolates was also seen in one of the Ghanaian isolates from Begoro. Pre- and post-treatment samples from Burkina Faso, had the D1525E mutation which was seen in four Ghanaian isolates. Henriques et al. [7] compared South East Asian and African phenotypes of the pfubp1 gene and detected significant differences in the genetic signatures. The recent implication of SNPs in these genes, especially pfap2mu S160N and pfubp1 E1528D and D1525E in ART resistance, raises a genuine concern due to their presence in Ghanaian isolates.

Of the three sites, Begoro (forest) had the most pfap2mu mutations (93%) followed by Cape-Coast (coastal savannah) (86%) and Navrongo (guinea savannah) (88%). Despite this observation, there is comparatively higher diversity in the mutations in Navrongo isolates with 72 different SNPs. Most of the isolates (63%) had more than one mutation. The high diversity of SNPs in Navrongo, where there is intense seasonal transmission of malaria, is expected. For pfubp1, Navrongo had the most mutations (96%), followed by Cape Coast (87%) and Begoro (86%). It is quite interesting to observe diversity of mutations from both genes from the guinea savannah zone. However, it must be emphasised that transmission intensity does not affect the evolution of resistance but plays a major role in the spread of resistance genotypes [18]. Therefore, discussing our observations along the line of different transmission intensities from the three distinct ecological zones will be premature.

Insertions/deletions (indels) identified in the Ghanaian isolates were similar to those observed in Burkina Faso, Kenya and the UK patients from Liberia and Uganda [7, 8]. The most common indels, observed in the isolates from the Ghanaian and the other African countries resulted from an insertion of AAT which resulted in an asparagine and lysine residues at codons 226 and 233, respectively [7, 8]. Indels of one to six amino acids were observed for the pfubp1 gene in the Ghanaian isolates and these were similar to those seen in Kenya and Burkina Faso [7, 8]. These resulted from an insertion of a KYD, KYE or KNE amino acids at codons ranging from 1516 to 1535. Most of the indels that resulted in a frameshift were caused by a deletion or insertion of either a guanosine or thymidine nucleotide.

The presence of the molecular markers implicated in drug resistance is of great importance in their role in modulating drug susceptibility and subsequently the prediction of the dynamics of resistance [23]. The spread of P. falciparum resistance to ARTs is a real global challenge and therefore insights into the mechanisms of drug action and resistance are critical for early detection of resistance. The detection and characterisation of these mutations in post-treatment Ghanaian isolates is the way forward for further validation of their roles in conferring resistance. This study has, therefore, highlighted the existence of delayed clearance markers of the pfap2mu and pfubp1 genes in circulating parasites in Ghana and will serve as baseline data for future surveillance studies.

Conclusions

The identification of molecular markers of ART resistance in Ghanaian isolates has implications for the development of ACT resistance especially for AL use. The findings from this study give first-hand information on potential molecular markers of ART resistance in Ghana and as such highlight the possibility of circulating parasites with reduced susceptibility to ACTs in use. Further investigations are underway to ascertain their contribution to the less than 100% cure rates observed, particularly for AL.

Additional file

Table S1. The list of all observed pfap2mu SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites. Table S2. The list of pfap2mu SNPs from five isolates with at least 20 SNPs per sample. Table S3. The list of all observed pfubp1 SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites. (XLSX 41 kb)

Acknowledgements

The research work presented was funded by the Global Fund to fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM)/ National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP, Ghana). The funding covered the field work for the collection of the samples and the laboratory analysis. The authors wish to thank the Director of NMIMR, Professor Kwabena Bosompem, for his permission to publish this article.

Funding

This study was funded by the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP, Ghana). The funders stated played no role in the design of the study, sample collection, analysis and interpretation of results as well as manuscript preparation.

Availability of data and materials

The observed SNPs from the sequence data from which the conclusions of this manuscript were drawn are available as Additional file 1: Table S1. The list of all observed pfap2mu SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites. Table S2. The list of pfap2mu SNPs from five isolates with at least 20 SNPs per sample. Table S3. The list of all observed pfubp1 SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites.

Abbreviations

- ACT

artemisinin-based combination therapy

- AL

artemether-lumifantrine

- ART

artemisinin

- AS-AQ

artesunate-amodiaquine

- DUB

deubiquitinating enzyme

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- IRS

indoor residual spraying

- ITNS

insecticide-treated mosquito nets

- NMCP

National Malaria Control Programme

- nPCR

nested polymerase chain reaction

- NS

non-synonymous mutations

- pfap2mu

P. falciparum adaptor protein complex 2 mu subunit gene

- pfk13

P. falciparum kelch propeller domain on chromosome 13

- pfubp1

P. falciparum ubiquitin specific protease 1 gene

- SEA

Southeast Asia

- SNPs

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- SYN

synonymous mutations

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

NOD, NBQ, GF, BA and KAK conceived and designed the study. TA, NAAE and SM did the laboratory analysis and generated molecular data. TA, NAAE and OCKH conducted data analysis. TA and NAAE drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was given by the NMIMR Institutional Review Board (IRB). The samples were taken after parents or guardians of the children gave their consent. This work is part of an ongoing surveillance of antimalarial drug efficacy studies in Ghana approved by the NMIMR IRB (CPN032/05-06a).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-018-2762-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Tryphena Adams, Email: tadams001@st.ug.edu.gh.

Nana Aba A. Ennuson, Email: naaennuson@st.ug.edu.gh

Neils B. Quashie, Email: nquashie@noguchi.ug.edu.gh

Godfred Futagbi, Email: gfutagbi@ug.edu.gh.

Sena Matrevi, Email: smatrevi@noguchi.ug.edu.gh.

Oheneba C. K. Hagan, Email: ockhagan@st.ug.edu.gh

Benjamin Abuaku, Email: babuaku@noguchi.ug.edu.gh.

Kwadwo A. Koram, Email: kkoram@noguchi.ug.edu.gh

Nancy O. Duah, Email: nduah@noguchi.ug.edu.gh

References

- 1.WHO. Malaria Fact Sheet 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/. Accessed 08 June 2017.

- 2.WHO. Malaria Fact Sheet: World Malaria Day 2016. www.who.int/malaria/media/world-malaria-day-2016/en. Accessed 22 Nov 2016.

- 3.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505(7481):50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MalariaGen: MalariaGen Plasmodium falciparum Community Project. Genomic epidemiology of artemisinin resistant malaria. eLife. 2016;5:e08714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ouattara A, Kone A, Adams M, Fofana B, Maiga AW, Hampton S, et al. Polymorphisms in the K13-propeller gene in artemisinin-susceptible Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Bougoula-Hameau and Bandiagara, Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(6):1202–1206. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamau E, Campino S, Amenga-Etego L, Drury E, Ishengoma D, Johnson K, et al. K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(8):1352–1355. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriques G, Hallett RL, Beshir KB, Gadalla NB, Johnson RE, Burrow R, et al. Directional selection at the pfmdr1, pfcrt, pfubp1, and pfap2mu loci of Plasmodium falciparum in Kenyan children treated with ACT. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(12):2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutherland CJ, Lansdell P, Sanders M, Muwanguzi J, van Schalkwyk DA, Kaur H, et al. Pfk13-independent treatment failure in four imported cases of Plasmodium falciparum malaria treated with artemether-lumefantrine in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2017;61(3):e02382–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Henriques G, van Schalkwyk DA, Burrow R, Warhurst DC, Thompson E, Baker DA, et al. The Mu subunit of Plasmodium falciparum clathrin-associated adaptor protein 2 modulates in vitro parasite response to artemisinin and quinine. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2015;59(5):2540–2547. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04067-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson KD. The discovery of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15280–15282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504842102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriques G, Martinelli A, Rodrigues L, Modrzynska K, Fawcett R, Houston DR, et al. Artemisinin resistance in rodent malaria - mutation in the AP2 adaptor mu-chain suggests involvement of endocytosis and membrane protein trafficking. Malar J. 2013;12:118. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abuaku B, Duah N, Quaye L, Quashie N, Malm K, Bart-Plange C, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine combinations in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in two ecological zones in Ghana. Malar J. 2016;15(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-1080-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duah NO, Matrevi SA, de Souza DK, Binnah DD, Tamakloe MM, Opoku VS, et al. Increased pfmdr1 gene copy number and the decline in pfcrt and pfmdr1 resistance alleles in Ghanaian Plasmodium falciparum isolates after the change of anti-malarial drug treatment policy. Malar J. 2013;12:377. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price RN, Cassar C, Brockman A, Duraisingh M, van Vugt M, White NJ, et al. The pfmdr1 gene is associated with a multidrug-resistant phenotype in Plasmodium falciparum from the western border of Thailand. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 1999;43(12):2943–2949. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price RN, Uhlemann AC, Brockman A, McGready R, Ashley E, Phaipun L, et al. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):438–447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16767-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson CM, Volkman SK, Thaithong S, Martin RK, Kyle DE, Milhous WK, et al. Amplification of pfmdr 1 associated with mefloquine and halofantrine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum from Thailand. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;57(1):151–160. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90252-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golassa L, Kamugisha E, Ishengoma DS, Baraka V, Shayo A, Baliraine FN, et al. Identification of large variation in pfcrt, pfmdr-1 and pfubp-1 markers in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Ethiopia and Tanzania. Malar J. 2015;14:264. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0783-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastings IM, Watkins WM, White NJ. The evolution of drug-resistant malaria: the role of drug elimination half-life. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357(1420):505–519. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genom Res. 2001;11(5):863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nature Protoc. 2009;4(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, Ambudkar SV. A "silent" polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science. 2007;315(5811):525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1135308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borrmann S, Straimer J, Mwai L, Abdi A, Rippert A, Okombo J, et al. Genome-wide screen identifies new candidate genes associated with artemisinin susceptibility in Plasmodium falciparum in Kenya. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3318. doi: 10.1038/srep03318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwansa-Bentum B, Ayi I, Suzuki T, Otchere J, Kumagai T, Anyan WK, et al. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from southern Ghana exhibit polymorphisms in the SERCA-type PfATPase6 though sensitive to artesunate in vitro. Malar J. 2011;10:187. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The list of all observed pfap2mu SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites. Table S2. The list of pfap2mu SNPs from five isolates with at least 20 SNPs per sample. Table S3. The list of all observed pfubp1 SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites. (XLSX 41 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The observed SNPs from the sequence data from which the conclusions of this manuscript were drawn are available as Additional file 1: Table S1. The list of all observed pfap2mu SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites. Table S2. The list of pfap2mu SNPs from five isolates with at least 20 SNPs per sample. Table S3. The list of all observed pfubp1 SNPs in Ghanaian isolates from the three study sites.