To the Editor—The effective treatment and prophylaxis of bacterial infections are essential to guarantee the safety of surgical interventions, from routine procedures to organ transplantation. The emergence of carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE) threatens the ability to successfully perform these life-saving interventions [1].

Klebsiella pneumoniae producing NDM, an Ambler class B metallo-β-lactamase that hydrolyzes carbapenems and other β-lactams except for aztreonam, was first reported in 2009 [2]. Worldwide dissemination of NDM-producing bacteria has occurred from endemic areas in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and the Balkans [2]. Similarly, OXA-48, a class D carbapenemase, has achieved broad distribution among K. pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae, especially in Turkey and neighboring regions of Southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East [1]. In the United States, OXA-48 and NDM-1 remain rare and CP-CRE is more frequently mediated by the serine β-lactamase K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) [1].

CASE PRESENTATION

A 35-year-old woman from Turkey was admitted to a hospital in Miami, Florida, to undergo evaluation for kidney and intestinal transplants. The patient suffered from Gardner syndrome with familial polyposis and invasive desmoid tumors that required multiple bowel resections. Complications included small bowel obstructions, intestinal fistulas, and bilateral ureteral obstruction with nephropathy, requiring placement of bilateral nephrostomy catheters. The patient did not have a previous history of infections with multidrug-resistant organisms.

Upon admission, she reported dysuria and right flank pain. Physical examination revealed purulent discharge from the exit site of a nephrostomy catheter. Urine culture grew K. pneumoniae. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed an isolate that was extensively drug resistant (XDR), including to all β-lactams and aztreonam, ceftazidime-avibactam, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and colistin (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] = 8 µg/mL). The isolate possessed an MIC of 2 μg/mL to tigecycline and 12 μg/mL to fosfomycin (Supplementary Data). The Rapid Carb Screen assay (Rosco Diagnostica, Taastrup, Denmark) was performed and the result suggested presence of a carbapenemase.

Further genetic characterization of the mechanisms of carbapenem resistance was pursued. Colonies of K. pneumoniae obtained from the original urine sample were inoculated into blood culture bottles, incubated overnight, and analyzed with the Verigene Gram-Negative Blood Culture Test (Nanosphere, Northbrook, Illinois), detecting blaNDM, blaOXA, and blaCTX-M-15. Results were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction amplification and DNA sequencing. Multilocus sequence typing determined that the isolate belonged to sequence type (ST) 14. Plasmids of 3 types, HIB-M/FIB-M, L, and R, were also present (Supplementary Data).

The patient was treated with a combination of oral fosfomycin and intravenous ertapenem and meropenem for 14 days (Supplementary Data) [3]. Both nephrostomy catheters were exchanged. Klebsiella pneumoniae was eradicated from the urine and signs of infection resolved. Rectal surveillance cultures intermittently showed the presence of XDR K. pneumoniae with the same molecular characteristics as the initial isolate.

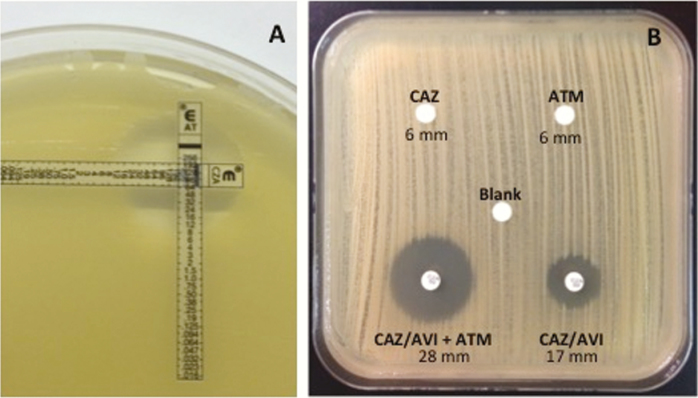

In preparation for transplantation, a perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis regimen was designed. Knowing from DNA sequencing that OXA-48, CTX-M-15, and NDM-1 were present, a regimen of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam was designed based on previous experience [4–6]. Etest and disk diffusion studies confirmed the synergy of this combination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Synergy testing between ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI) and aztreonam (ATM) performed by Etest (A) and disk diffusion (B).

Four months after admission, the patient required surgery to debulk the tumor mass and remove most of her small bowel. Ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam were administered for 3 days (in addition to vancomycin and micafungin), effectively preventing postsurgical infections. Six months after admission, the patient underwent kidney and isolated intestinal transplant, and ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam were again used as part of perioperative surgical prophylaxis. Other antibiotics used at the time included daptomycin (due to co-colonization with vancomycin-resistant enterococci), metronidazole, and fluconazole (see Supplementary Data for dosing). Antimicrobial coverage was extended to 4 weeks because of repeated surgeries to address bleeding and an anastomotic leak. Postsurgical infections did not occur during this regimen or after its discontinuation despite evidence of rectal colonization with XDR K. pneumoniae in surveillance cultures. At the time of this communication, the patient was doing well at 9 months post-transplant.

This report of XDR K. pneumoniae producing OXA-48, CTX-M-15, and NDM-1 in a young woman from Turkey who underwent multivisceral transplantation in the United States highlights the significant threat posed by CP-CRE to a particularly vulnerable group of patients. Individualized therapy was implemented based on understanding of the mechanisms of resistance and the activity of novel antibiotic combinations against CP-CRE. Applying innovative molecular diagnostic techniques to maximize the utility of our limited antibiotic arsenal to achieve successful outcomes is a clear benefit of “precision medicine.”

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Financial support. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (award numbers R01AI100560, R01AI063517, and R01AI072219). This study was also supported in part by funds and/or facilities provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs (award number 1I01BX001974 to R. A. B.) from the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center VISN 10 (to R. A. B.).

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. D. P. N. has received research funding from and is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Merck & Co, Inc. F. P. is supported by Pfizer, Inc, Merck & Co, Inc, the Cleveland Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative, and the VISN 10 Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center, and has received consulting honoraria from Allergan. R. A. B. reports grants from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs Research and Development, and the VISN 10 Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center. R. A. B. also receives grants from Merck, Allergan, Wockhardt, Roche and Entasis. L. A. B. is a member of the advisory board of Nabriva Therapeutics and has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Pfizer, Inc. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Doi Y, Paterson DL. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 36:74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Worldwide dissemination of the NDM-type carbapenemases in gram-negative bacteria. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:249856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wiskirchen DE, Nordmann P, Crandon JL, Nicolau DP. In vivo efficacy of human simulated regimens of carbapenems and comparator agents against NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:1671–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mojica MF, Ouellette CP, Leber A et al. Successful treatment of bloodstream infection due to metallo-β-lactamase-producing Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in a renal transplant patient. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:5130–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crandon JL, Nicolau DP. Human simulated studies of aztreonam and aztreonam-avibactam to evaluate activity against challenging gram-negative organisms, including metallo-β-lactamase producers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:3299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall S, Hujer AM, Rojas LJ et al. Can ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam overcome beta-lactam resistance conferred by metallo-beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e02243–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.