Abstract

Introduction

Penetrating neck injury is a relatively uncommon trauma presentation with the potential for significant morbidity and possible mortality. There are no international consensus guidelines on penetrating neck injury management and published reviews tend to focus on traditional zonal approaches. Recent improvements in imaging modalities have altered the way in which penetrating neck injuries are now best approached with a more conservative stance. A literature review was completed to provide clinicians with a current practice guideline for evaluation and management of penetrating neck injuries.

Methods

A comprehensive MEDLINE (PubMed) literature search was conducted using the search terms ‘penetrating neck injury’, ‘penetrating neck trauma’, ‘management’, ‘guidelines’ and approach. All articles in English were considered. Articles with only limited relevance to the review were subsequently discarded. All other articles which had clear relevance concerning the epidemiology, clinical features and surgical management of penetrating neck injuries were included.

Results

After initial resuscitation with Advanced Trauma Life Support principles, penetrating neck injury management depends on whether the patient is stable or unstable on clinical evaluation. Patients whose condition is unstable should undergo immediate operative exploration. Patients whose condition is stable who lack hard signs should undergo multidetector helical computed tomography with angiography for evaluation of the injury, regardless of the zone of injury.

Conclusions

The ‘no zonal approach’ to penetrating neck trauma is a selective approach with superior patient outcomes in comparison with traditional management principles. We present an evidence-based, algorithmic and practical guide for clinicians to use when assessing and managing penetrating neck injury.

Keywords: Penetrating neck injury, Trauma, Management, Review

Introduction

Penetrating neck injury represents 5–10% of all trauma cases.1 It is important for clinicians to be familiar with management principles, as mortality rates can be as high as 10%.2 This can prove difficult however, as there are no international consensus guidelines and recent improvements in imaging modalities have altered the way in which such are now approached.3,4 Published guidance on the management of penetrating neck injury tends to focus on traditional approaches.3,5,6 This review provides a practical guide for the evaluation and management of penetrating neck injuries.

Background

Penetrating neck injury describes trauma to the neck that has breached the platysma muscle.6 The most common mechanism of injury worldwide is a stab wound from violent assault, followed by gunshot wounds, self harm, road traffic accidents and other high velocity objects.5,7 The neck is a complex anatomical region containing important vascular, aerodigestive and neurological structures that are relatively unprotected.7 Vascular injury may include partial or complete occlusion (most common), dissection, pseudoaneurysm, extravasation of blood or arteriovenous fistula formation.8 Arterial injury occurs in approximately 25% of penetrating neck injuries; carotid artery involvement is seen in approximately 80% and vertebral artery in 43%.2 Combined carotid and vertebral artery injury carry both major haemorrhagic and neurological concern.8 Aerodigestive injury occurs in 23–30% of patients with penetrating neck injuries and is associated with a high mortality rate.6 Pharyngo-oesophageal injuries are less common than laryngotracheal injuries but both are associated with a mortality rate of approximately 20%.7,9 Neurological structures at risk of involvement include the spinal cord, cranial nerves VII–XII, the sympathetic chain, peripheral nerve roots and brachial plexus. Spinal cord injury occurs infrequently (less than 1%), particularly in low velocity injuries such as stab wounds.10

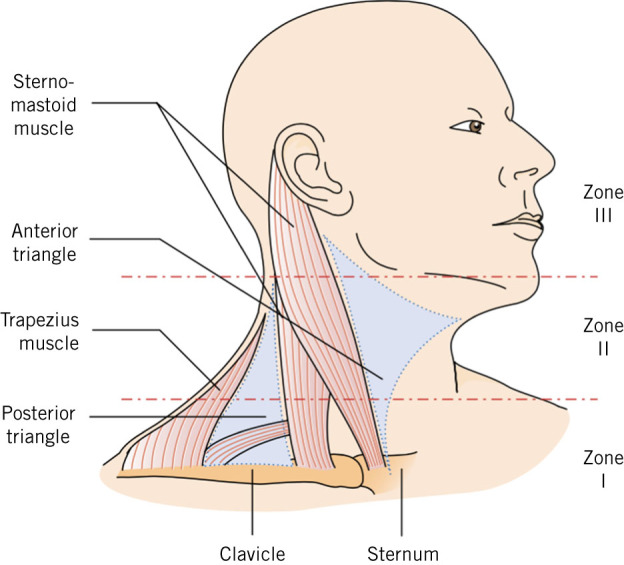

The assessment and management of penetrating trauma to the neck has traditionally centred on the anatomical zone-based classification first described by Monson et al. in 1969 (Fig 1).11,12 More recently, the rigidity of this zone-based algorithm has been challenged, especially with regard to the mandatory exploration for zone II injuries.12 Routine neck exploration in haemodynamically stable patients leads to a high rate of nontherapeutic intervention, missed injuries, increased length of hospital stay and an increased rate of complications.3,13,14 Additionally, Low et al. demonstrated in 2014 a poor correlation between the location of the external wound and the injuries to internal structures.15 These factors have brought into question the entire foundation of the traditional zonal approach. This review outlines a selective, non-zonal approach to penetrating neck injuries, where the entire neck is treated as a single entity.

Figure 1.

Classification of anatomical zones of the neck (Monson 1969). Zone 1 extends from clavicles to cricoid, zone II from cricoid to angle of mandible, and zone III from angle of mandible to skull base.

Methods

A comprehensive MEDLINE (PubMed) literature search was conducted. The initial search strategy included terms ‘penetrating neck injury’ and ‘penetrating neck trauma’. Additional search terms such as ‘management’, ‘guidelines’ and ‘approach’ were subsequently used. All articles in English were given consideration. Articles with only limited relevance to the review were discarded. All other articles which had clear relevance concerning the epidemiology, clinical features and surgical management of penetrating neck injuries were included.

Initial assessment and stabilisation

Patients with penetrating neck injuries can decompensate rapidly and should be transported immediately to the nearest trauma centre. Impaled objects should not be removed in the field. A systematic approach to the management of penetrating neck trauma is critical. The initial evaluation and assessment involves resuscitation in accordance with the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) principles.4,5 Early inspection of a neck injury is advised to determine if the platysma muscle has been breached.4 Use of local anaesthesia facilitates a more accurate assessment of the wound.4 If the platysma is intact then, by definition, the wound is superficial. If the platysma is violated then it is a penetrating neck injury and the patient’s signs and symptoms govern how to proceed with management.4 Surgical consultation should be obtained in all penetrating neck injuries, particularly because the patient may initially appear stable but may decompensate rapidly. This is preferably achieved with an attending emergency otolaryngology team.

Cervical spine immobilisation is not routinely recommended in penetrating neck injuries.16 The incidence of unstable cervical spine fractures in penetrating neck injuries is very low and cervical spine collars may obscure clinical signs and impair intubation.17,18 The exceptions to this are if there is focal neurology or a high clinical suspicion for spinal injury in an unconscious or heavy intoxicated patient. Additionally, the incidence of cervical spine injury and cervical spinal cord injury has been demonstrated to be significantly different depending on the mechanism of injury.10 Penetrating neck injuries that result from high energy injuries, such as gun shots or blunt force as in motor vehicle accidents, are at higher risk of cervical spine injury and immobilisation needs to be considered.10

Airway management

Immediate consideration should be given to the airway in a systematic approach and must address the following questions:

Does the patient require immediate airway protection?

What is the best approach and technique for airway protection?

This initially includes careful clinical examination for injury to the aerodigestive tract (oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal or tracheal).13 Clinical signs of airway injury include hoarseness, stridor, dyspnoea, subcutaneous emphysema (in the absence of pneumothorax), bubbling from the wound and large volume hemoptysis.5,12 The best method of achieving definite airway control in the setting of penetrating neck injury will vary according to the clinical circumstances, clinical skill and hospital resources.19 It is imperative to be prepared for unexpected difficulty. Have available at least two suction devices, a range of different sized tracheal tubes, rescue airway devices and a surgical airway kit. Additionally, it is best to avoid airway techniques not performed with direct visualisation, as blind placement of a tracheal tube into a lacerated tracheal segment can create a false lumen outside the trachea or convert a partial tracheal laceration into a complete transection.19

When the airway is threatened but anatomic structures are preserved, we recommend rapid sequence intubation to secure the airway. Several studies at major trauma centres have found this to be a safe and effective approach to definite airway control.20–22 Bag and mask ventilation to preoxygenate in preparation for rapid sequence intubation or to reoxygenate following a failed attempt at intubation must be done with vigilance, as it may force air into injured tissue planes and distort airway anatomy or further disrupt surrounding soft tissue injury.19,20 If tracheal intubation is deemed necessary and the airway is predicted to be difficult because of distorted anatomy, we recommend fibreoptic intubation. Fibreoptic laryngoscopy and intubation allows the clinician to determine the integrity of the interior of the supraglottic and infraglottic airway while the patient maintains spontaneous respiration.21 This technique is limited by a patient’s level of cooperation and ability to tolerate the procedure.

Invasive airway management represents the standard approach when orotracheal intubation by any method is unsuccessful or contraindicated.22 Immediate indications for a surgical airway include massive upper airway distortion, massive midface trauma and inability to visualise the glottis because of heavy bleeding, oedema or anatomical disruption.19,23,24 Cricothyotomy and tracheotomy are the two most commonly used procedures for severe neck trauma.24 We recommend cricothyrotomy as the first surgical airway of choice, as it is the most direct, simple and safe way of bypassing upper airway obstruction or injury.24 This may be difficult in the presence of distorted neck anatomy or if an anterior neck haematoma or laryngeal injury is suspected and carries potential risk to the vocal cords.25 Tracheotomy may be necessary in the event of skeletal collapse, significant structural airway disruption and breakdown and/or partial or complete transection of the larynx or trachea.25 The tracheotomy incision should be made as low in the neck as possible to avoid further injury to the laryngotracheal complex. The cervical incision should be made vertically, which allows for inferior extension if becomes necessary to achieve better anatomic exposure.24 Tracheotomy, even when performed by experienced hands, is the primary cause of long-term laryngotracheal complications and should therefore only be performed if indicated.24

Surgery compared with conservative management

The decision to take a patient presenting with a penetrating neck injury immediately for surgical intervention is largely dependent on the physiological status and clinical findings on examination.12 If there is evidence of haemodynamic instability or what trauma centres refer to as ‘hard signs’ of injury to vital structures of the neck (Box 1), the patient should undergo operative exploration and bypass imaging.5,12,15 The absence of hard signs does not exclude injury to underlying structures and the decision to take the patient to the operating theatre therefore depends on whether the physiological status of the patient is unstable.13 Surgical techniques for repairing injury to vital structures are discussed below.

Box 1.

‘Hard signs’ indicating immediate explorative surgery in penetrating neck injury.

Shock

Pulsatile bleeding or expanding haematoma

Audible bruit or palpable thrill

Airway compromise

Wound bubbling

Subcutaneous emphysema

Stridor

Hoarseness

Difficulty or pain when swallowing secretions

Neurological deficits

Surgical management of vascular injury

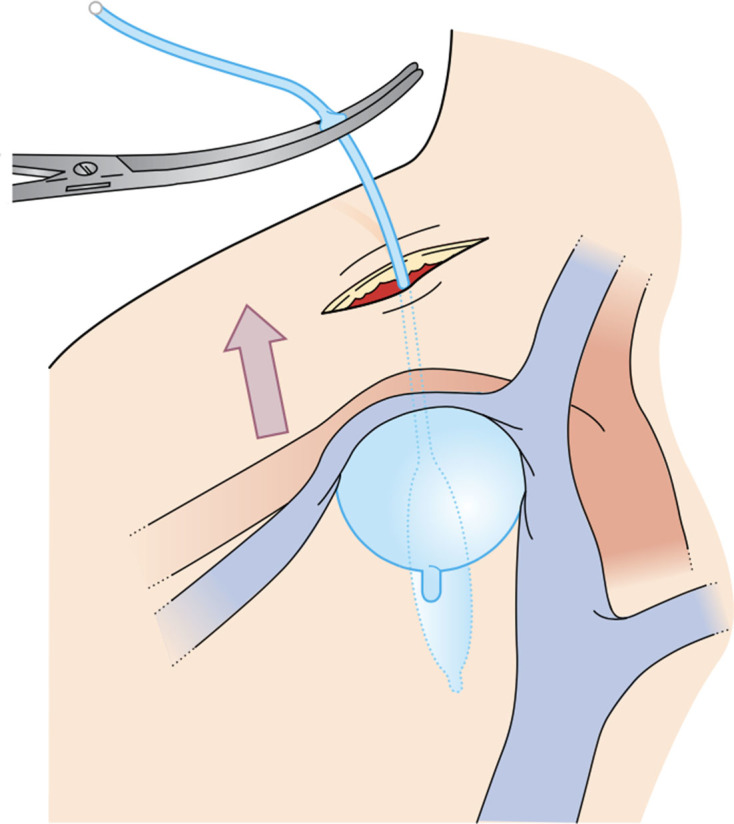

As exsanguination accounts for up to 50% of the mortality from penetrating neck injuries, we recommend that clinicians are familiar with haemorrhage control techniques in the interim of surgical intervention.5 Specific to penetrating neck injuries, bleeding that is not amenable to control through simple external compression can be amenable to Foley balloon catheter tamponade.5,23 This is a well-recognised technique for temporarily arresting bleeding and can sometimes avoid the need for emergency surgery. It involves introducing the Foley catheter into the wound, following the wound track and inflating the balloon with 10–15 ml of water until resistance is met (Fig 2). The catheter is then clamped and the neck wound is sutured (Fig 3).26 If compression or balloon tamponade successfully controls the haemorrhage, angiography can be arranged to identify the source of bleeding prior to operative or endovascular intervention.5

Figure 2.

Foley catheter balloon tamponade. A Foley catheter is introduced into the bleeding neck wound following the wound track. The balloon is inflated with 10–15 ml water or until resistance is felt. The catheter is clamped to prevent bleeding through the lumen. The neck wound is sutured around the catheter.

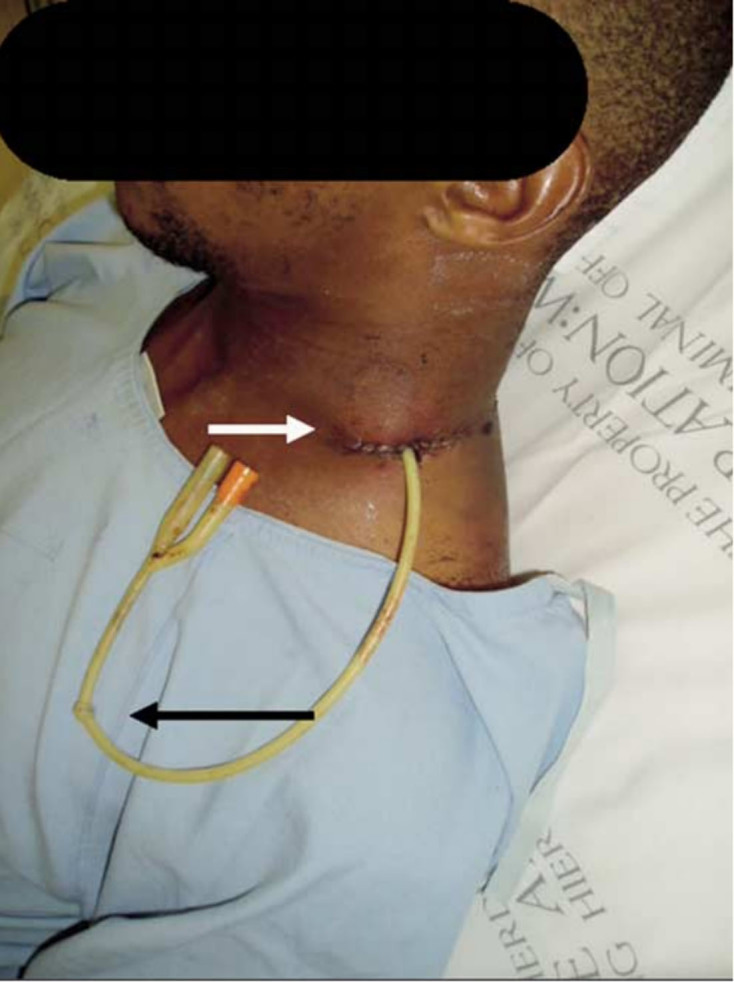

Figure 3.

Foley catheter balloon tamponade in a zone 2 neck injury. The catheter is knotted on itself (black arrow) acting as a clamp to prevent flow of blood through the lumen. The wound is suture around it (white arrow).

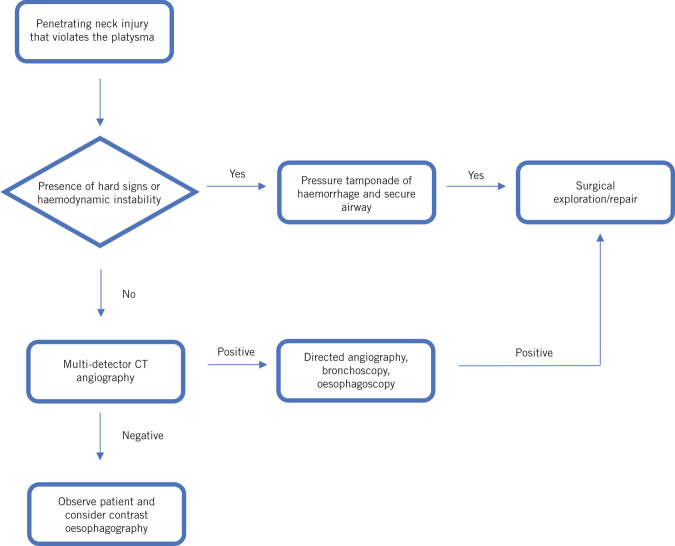

Figure 4.

Algorithm for no-zonal management of penetrating neck injury. Approach patients with a penetrating neck injury like any trauma patient with Advanced Trauma Life Support resuscitation. Patients who are unstable and demonstrating any of the ‘hard signs’ or visceral injury must be immediately taken for surgical exploration. All patients who are stable should have a multidetector helical computed tomography with angiography to evaluate for visceral injury.

If a vascular injury from a penetrating neck injury is suspected, immediate consultation with a vascular surgeon should be obtained. Zone 1 vascular injuries may also require input from a cardiothoracic surgeon as treatment may require a sternotomy or thoracotomy to gain proximal access to vascular structures.4 When a common or internal carotid artery injury is identified during a neck exploration, the consensus from the literature suggests that repair of the artery has superior patient outcomes than artery ligation.27,28 This is irrespective of whether or not a preoperative focal neurological deficit was present.27 Carotid repair methods are extensive and usually depend on location and size of the injury. The two most common techniques include transverse arteriorrhaphy with interrupted 6-0 polypropylene suture and vein or thin-walled polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch angioplasty with continuous 6-0 polypropylene suture.27 Isolated jugular venous injuries are generally innocuous as the low-pressure venous system usually tamponades or occludes without major haemorrhage.29

Surgical management of laryngotracheal injury

If injury to the laryngotracheal complex is suspected, panendoscopy and bronchoscopy under general anaesthesia should precede surgical exploration.5,24 If an injury is identified, repair is usually indicated, with the exception of small mucosal defects or undisplaced fractures of the laryngeal framework, which can be managed conservatively.5 Significant skeletal fractures and associated soft tissue injuries warrant open repair.3 A review of the details of each open surgical repair is beyond the scope of this review. Stenting may also be used to manage severely displaced laryngeal fractures that may cause skeletal instability or breakdown. Stents also have the added benefit of bolstering the soft tissues and arytenoids, impeding haematomas, web formation and aspiration.24 Surgeons who expect to be involved in acute laryngotracheal trauma must have access to a variety of stent designs and sizes at all times.24

Surgical management of pharyngo-oesophageal injury

Cervical oesophageal injuries are less common because of the central and protected position of the oesophagus. These are often silent injuries with no findings on clinical examination.5 All patients with suspected oesophageal injury must have intravenous antibiotics, nil by mouth and given surgical nutrition.30 If patients demonstrate hard signs of oesophageal injury or if early imaging demonstrates oesophageal perforation, operative repair is generally required.31 If not treated early, oesophageal injuries may cause mediastinitis and abscess or empyema formation from leakage of gastric contents.30

Surgical treatment of oesophageal injuries depends on the timing since the inflicted injury. Patients presenting within 12 hours of injury may undergo direct suture repair and drainage.30 After 12 hours of injury, morbidity and mortality increases and direct repair is less likely to be successful.30,32 These patients should ideally undergo debridement and drainage with a planned delayed repair. The majority of studies suggest that repair with a single layer is equally safe and effective as a double-layer repair in a penetrating neck injury.33,34 All patients should be monitored closely and returned to the operating theatre for repeat exploration if signs of infection develop.

Patients who are stable

Historically, the management of patients without hard signs was dependent on the zone of injury.12,35 Zone II injuries, which constitute the majority of penetrating neck injuries, always underwent mandatory surgical exploration.35 Zone I and III injuries were evaluated more selectively due to difficult anatomic accessibility.12 Further evaluation often included angiography, bronchoscopy and/or oesophagoscopy – a labour and resource-intensive process often requiring input from multiple specialities.12 Although these studies have high sensitivity for detecting respective injuries, they are also invasive to the patient and carry a small but significant risk of complications. Over the 2000s, there have been numerous studies with evidence that suggests approaching the neck with a ‘no zone’ approach provides superior outcomes for the patient with a penetrating neck injuriy.12,14,15 This entails clinicians assessing the entire neck as a single entity and managing penetrating injuries with a selective approach based on the clinical findings and the physiological status of the patient.

While there are studies from high-volume trauma centres in the United States recommending physical examination alone is sufficient for penetrating neck injury evaluation, most trauma centres have a relatively low volume of such injuries and, consequently, clinicians are less experienced in managing these injuries.4 For these reasons, we recommend clinicians consider multidetector helical computed tomography with angiography (MDCT-A) in the evaluation of patients who do not require immediate operative intervention.12 This imaging modality has been recognised to be both highly sensitive and specific in detecting vascular, laryngotracheal and many pharyngo-oesophageal injuries, thereby eliminating the need for multiple imaging studies to assess each type of injury.5,13,35,36 It can also provide information on the trajectory of the wound track and suggest whether imaging of the thorax is also required.37

MDCT-A has resulted in in a significant decrease in formal neck explorations and a virtual elimination of exploratory surgery.13 One limitation of MDCT-A is the potential to miss pharyngo-oesophageal injury, with some studies reporting the sensitivity to be as low as 53%.9,12 This, coupled with the high mortality rate of pharyngo-oesophageal injury, means that additional imaging in a stable patient with potential pharyngo-oesophageal injury is often required. A contrast swallow is usually performed first, followed by a flexible oesophagoscopy in the event of non-diagnosis. Flexible oesophagoscopy has a sensitivity close to 100%.38

Routine evaluation of all patients who are stable with MDCT-A is therefore advised regardless of the zone of injury. Further assessment with angiography, bronchoscopy, contrast swallow/flexible oesophagoscopy or surgical exploration may be guided by the MDCT-A findings.5

Conclusions

The no-zonal approach to penetrating neck injury evaluation and management is contemporary and against the grain of the anatomical zones management algorithms that have guided clinicians over the past 50 years. Evidence is accumulating to suggest that the non-zonal approach is superior over traditional approaches to penetrating neck trauma, especially with respect to reduced negative neck explorations. We have suggested a no-zonal algorithmic approach which employs MDCT-A for clinicians to use in the evaluation and management of penetrating neck injuries. There are currently no international guidelines and generally a lack of consensus in the literature regarding optimum assessment and treatment of penetrating neck injuries. Further research is therefore warranted to continue advancing our understanding of the management of penetrating neck injuries.

References

- 1.Vishwanatha B, Sagayaraj A, Huddar SG et al. Penetrating neck injuries. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007; : 221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saito N, Hito R, Burke PA, Sakai O. Imaging of penetrating injuries of the head and neck: current practice at a level I trauma center in the United States. Keio J Med 2014; : 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain Zaidi SM, Ahmad R. Penetrating neck trauma: a case for conservative approach. Am J Otolaryngol 2011; : 591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siau RT, Moore A, Ahmed T et al. Management of penetrating neck injuries at a London trauma centre. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013; : 2,123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgess CA, Dale OT, Almeyda R, Corbridge RJ. An evidence based review of the assessment and management of penetrating neck trauma. Clin Otolaryngol 2012; : 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperry JL, Moore EE, Coimbra R et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: penetrating neck trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; : 936–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmoodie M, Sanei B, Moazeni-Bistgani M, Namgar M. Penetrating neck trauma: review of 192 cases. Arch Trauma Res 2012; : 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babu A, Garg H, Sagar S et al. Penetrating neck injury: collaterals for another life after ligation of common carotid artery and subclavian artery. Chin J Traumatol 2017; : 56–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant AS, Cerfolio RJ. Esophageal trauma. Thorac Surg Clin 2007; : 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhee P, Kuncir EJ, Johnson L et al. Cervical spine injury is highly dependent on the mechanism of injury following blunt and penetrating assault. J Trauma 2006; : 1,166–1,170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monson DO, Saletta JD, Freeark RJ. Carotid vertebral trauma. J Trauma 1969; : 987–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiroff AM, Gale SC, Martin ND et al. Penetrating neck trauma: a review of management strategies and discussion of the 'No Zone' approach. Am Surg 2013; : 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborn TM, Bell RB, Qaisi W, Long WB. Computed tomographic angiography as an aid to clinical decision making in the selective management of penetrating injuries to the neck: a reduction in the need for operative exploration. J Trauma 2008; : 1,466–1,471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roepke C, Benjamin E, Jhun P, Herbert M. Penetrating Neck Injury: What's In and What's Out? Ann Emerg Med 2016; : 578–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low GM, Inaba K, Chouliaras K et al. The use of the anatomic 'zones' of the neck in the assessment of penetrating neck injury. Am Surg 2014; : 970–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuke LE, Pons PT, Guy JS et al. Prehospital spine immobilization for penetrating trauma––review and recommendations from the Prehospital Trauma Life Support Executive Committee. J Trauma 2011; : 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connell RA, Graham CA, Munro PT. Is spinal immobilisation necessary for all patients sustaining isolated penetrating trauma? Injury 2003; : 912–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanderlan WB, Tew BE, McSwain NE, Jr. Increased risk of death with cervical spine immobilisation in penetrating cervical trauma. Injury 2009; : 880–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tallon JM, Ahmed JM, Sealy B. Airway management in penetrating neck trauma at a Canadian tertiary trauma centre. CJEM 2007; : 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youssef N, Raymer KE. Airway management of an open penetrating neck injury. CJEM 2015; : 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharya P, Mandal MC, Das S et al. Airway management of two patients with penetrating neck trauma. Indian J Anaesth 2009; : 348–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandavia DP, Qualls S, Rokos I. Emergency airway management in penetrating neck injury. Ann Emerg Med 2000; : 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Waes OJ, Cheriex KC, Navsaria PH et al. Management of penetrating neck injuries. Br J Surg 2012; (Suppl 1): 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee WT, Eliashar R, Eliachar I. Acute external laryngotracheal trauma: diagnosis and management. Ear Nose Throat J 2006; : 179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koletsis E, Prokakis C, Baltayiannis N et al. Surgical decision making in tracheobronchial injuries on the basis of clinical evidences and the injury’s anatomical setting: a retrospective analysis. Injury 2012; : 1,437–1,441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scriba MF, Navsaria PH, Nicol AJ et al. Foley-catheter balloon tamponade (FCBT) for penetrating neck injuries (PNI) at Groote Schuur Hospital: an update. S Afr J Surg 2017; : 64. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feliciano DV. Management of penetrating injuries to carotid artery. World J Surg 2001; : 1,028–1,035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teehan EP, Padberg FT Jr, Thompson PN et al. Carotid arterial trauma: assessment with the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as a guide to surgical management. Cardiovasc Surg 1997; : 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar SR, Weaver FA, Yellin AE. Cervical vascular injuries: carotid and jugular venous injuries. Surg Clin North Am 2001; : 1331–44, xii–xiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madiba TE, Muckart DJ. Penetrating injuries to the cervical oesophagus: is routine exploration mandatory? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003; : 162–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tisherman SA, Bokhari F, Collier B et al. Clinical practice guideline: penetrating zone II neck trauma. J Trauma 2008; : 1,392–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Triggiani E, Belsey R. Oesophageal trauma: incidence, diagnosis, and management. Thorax 1977; : 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohlala ML, Ramoroko SP, Ramasodi KP et al. A technical approach to tracheal and oesophageal injuries. S Afr J Surg 1994; : 114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong WB, Detar TR, Stanley RB. Diagnosis and management of external penetrating cervical esophageal injuries. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994; : 863–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brywczynski JJ, Barrett TW, Lyon JA, Cotton BA. Management of penetrating neck injury in the emergency department: a structured literature review. Emerg Med J 2008; : 711–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inaba K, Munera F, McKenney M et al. Prospective evaluation of screening multislice helical computed tomographic angiography in the initial evaluation of penetrating neck injuries. J Trauma 2006; : 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steenburg SD, Sliker CW, Shanmuganathan K, Siegel EL. Imaging evaluation of penetrating neck injuries. Radiographics 2010; : 869–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feliciano DV. Penetrating Cervical Trauma. Current Concepts in Penetrating Trauma, IATSIC Symposium, International Surgical Society, Helsinki, Finland, August 25–29, 2013. World J Surg 2015; : 1,363–1,372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]