Abstract

Objective

Men with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) traits are at an increased risk for consuming alcohol and perpetrating intimate partner violence (IPV). However, previous research has neglected malleable mechanisms potentially responsible for the link between ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration. Efforts to improve the efficacy of batterer intervention programs (BIPs) would benefit from exploration of such malleable mechanisms. The present study is the first to examine distress tolerance as one such mechanism linking men's ASPD traits to their alcohol problems and IPV perpetration.

Methods

Using a cross-sectional sample of 331 men arrested for domestic violence and court-referred to BIPs, the present study used structural equation modeling to examine pathways from men's ASPD traits to IPV perpetration directly and indirectly through distress tolerance and alcohol problems.

Results

Results supported a two-chain partial mediational model. ASPD traits were related to psychological aggression perpetration directly and indirectly via distress tolerance and alcohol problems. A second pathway emerged by which ASPD traits related to higher levels of alcohol problems, which related to psychological aggression perpetration. Controlling for psychological aggression perpetration, neither distress tolerance nor alcohol problems explained the relation between ASPD traits and physical assault perpetration.

Conclusion

These results support and extend existing conceptual models of IPV perpetration. Findings suggest intervention efforts for IPV should target both distress tolerance and alcohol problems.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, distress tolerance, alcohol, men, domestic violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a prevalent and serious public health problem, which may include partner-directed psychological aggression and physical assault. Approximately 22% of women suffer from severe physical assault by an intimate partner in their lifetime with even more suffering from psychological aggression (see Hamby, 2014, for a review). Individuals who are victims of IPV experience a range of physical and mental health consequences which contribute to health care costs exceeding $19.3 million annually (Black, 2011; Rivara et al., 2007; Ulloa & Hammett, 2016). Understanding correlates and malleable risk factors for IPV perpetrated by men is essential to the development of intervention programs aimed at reducing this harmful and costly public health problem. The present study aims to inform intervention efforts by examining pathways from men's antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) traits to IPV perpetration directly and indirectly through distress tolerance and alcohol problems. Associations are examined in a sample of men arrested for domestic violence and court-referred to batterer intervention programs (BIPs).

Existing predictive models of men's IPV perpetration posit that distal factors (e.g., personality traits and drinking patterns) interact with proximal variables (e.g., situational factors and substance intoxication) to increase the likelihood of IPV perpetration during relationship conflict (e.g., Bell & Naugle, 2008; Stuart, Meehan, Moore, Morean, Hellmuth, & Follansbee, 2006). Two of the most well-documented distal factors linked to men's IPV perpetration are ASPD traits (e.g., a pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others originating in early childhood and accompanied by impulsivity, irritability, and aggressiveness; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and alcohol problems (Foran & O'Leary, 2008; Holtzworth-Munroe, Meehan, Herron, Rehman, & Stuart, 2000; Stuart et al., 2006; Taft et al., 2010). Given the robust association between ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration, some researchers suggest that individuals with ASPD traits may be more inclined to engage in problem drinking (Maclean & French, 2014) which thereby increases their risk of IPV perpetration (Holtzworth-Munroe et al., 2000; Ross, 2011). Indeed, using a sample of men arrested for domestic violence and court-ordered to attend batterer intervention programs (BIPs), Stuart and colleagues (2006) found support for a conceptual model by which men's ASPD traits related to their alcohol problems, and both significantly predicted men's physical assault perpetration indirectly through psychological aggression perpetration.

Despite the robust associations between men's ASPD traits and alcohol problems, and their associations with IPV perpetration, relatively little research has explicated malleable factors that may be responsible for such associations. Efforts to prevent IPV would benefit from further exploration of mechanisms that account for the tendency of men with ASPD traits to engage in problematic alcohol use and IPV. Thus, the present study sought to examine distress tolerance as one such mechanism among men arrested for domestic violence and court-referred to BIPs.

Distress Tolerance and ASPD Traits

As part of a higher-order emotion regulation construct, distress tolerance is conceptualized as an ability to withstand aversive internal and external states elicited by a stressor (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010). Distress tolerance consists of one's evaluations and expectations of aversive affect with regards to tolerability, appraisal, regulation, and absorption of affect (Simons & Gaher, 2005). Informed by Emotion Dysregulation Theory (Cole, Mitchel, & Teti, 1994), low distress tolerance influences affect regulation by increasing use of impulsive behaviors to alleviate distress (Cummings et al., 2013; Leyro et al., 2010; Simons & Gaher, 2005). That is, individuals with lower distress tolerance are thought to be impulsive because they find it difficult to pursue longer-term solutions to internal and external problems. Alcohol use and IPV are two such impulsive behaviors that may quickly ameliorate distress and are thus maintained through negative reinforcement for individuals with low distress tolerance (Leyro et al., 2010). Indeed, conceptual frameworks (e.g., Bell & Naugle, 2008) hypothesize that IPV perpetration exists within a system affected by an individual's behavioral repertoire deficits (e.g., low distress tolerance skills) and maintained by negative reinforcement (e.g., reducing distress via maladaptive behaviors such as IPV perpetration).

Recent research suggests that low distress tolerance co-occurs with ASPD traits. Cummings and colleagues (2013) examined adolescents over a four-year period and found that levels of distress tolerance was longitudinally associated with externalizing behaviors associated with ASPD (i.e., traits of conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Furthermore, relative to individuals with psychopathic traits who are believed to have hypo-reactivity to emotionally-salient stimuli, individuals with ASPD traits reported lower levels of distress tolerance (Sargeant, Daughters, Curtin, Schuster, & Lejuez, 2011). Men in substance use treatment with ASPD traits exhibited lower levels of distress tolerance than did individuals without ASPD traits (Daughters, Sargeant, Bornovalova, Gratz, & Lejuez, 2008). Together, past research suggests that men with ASPD traits exhibit an inability or unwillingness to persist in the presence of distressing experiences, which may then explain the association between ASPD traits and other problematic behaviors.

Distress Tolerance, Alcohol Use, and IPV Perpetration

Researchers have yet to concurrently examine men's ASPD traits, distress tolerance, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration. However, prior research suggests it is plausible that IPV perpetration and problematic alcohol use are motivated by efforts to circumvent internal and external experiences perceived as too aversive to withstand (i.e., distress intolerance). These relations may be more evident in men with ASPD traits due to their lower levels of distress tolerance (Sargeant et al., 2011). For instance, higher ASPD traits and use of alcohol during stressful situations were associated with increased rates of IPV among men with a history of IPV perpetration (Taft et al., 2010). Though distress tolerance was not directly examined, Taft and colleagues’ findings suggest alcohol may be used problematically to escape distress for men with ASPD traits, and such men are also more inclined to react aggressively within romantic relationships.

Using a sample of men in treatment for substance use disorders, Shorey, Elmquist, Strauss, Anderson, and Stuart (2015) found an inverse relationship between distress tolerance and both psychological and physical IPV perpetration. Similarly, Eckhardt (2007) found that partner-violent men who were social drinkers were more likely to report greater feelings of anger and display more aggressive verbalizations in response to provocation. Though Eckhardt (2007) did not examine distress tolerance, it is plausible that partner-violent men may have lower tolerance for aversive affect and greater propensity to respond aggressively as a result. Together, these findings provide preliminary evidence for distress tolerance as a potential malleable mechanism underlying the relations between ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration among men.

Summary and Hypotheses

ASPD traits and alcohol problems are robust predictors of IPV perpetration. Both theory and research suggest that poor distress tolerance is evident in men with ASPD traits (Daughters et al., 2008; Sargeant et al., 2011), and that low distress tolerance may increase the likelihood that such men will engage in problematic alcohol use (Ali, Ryan, Beck, & Daughters, 2013; Taft et al., 2010), a known predictor of IPV perpetration. Furthermore, low distress tolerance was implied as one underlying characteristic in men who perpetrate IPV (Shorey et al., 2015; Taft et al., 2010). Despite the theoretical and empirical support linking distress tolerance to ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration, researchers have yet to examine whether distress tolerance mediates the relation between ASPD traits and IPV perpetration.

Informed by existing conceptual models of IPV perpetration (e.g., Stuart et al., 2006) and Emotion Dysregulation Theory (Cole et al., 1994), the present study sought to evaluate the indirect effects of ASPD traits on men's IPV perpetration through distress tolerance and alcohol problems. Our specific hypotheses were as follows:

ASPD traits would relate to low distress tolerance, which would relate to increased alcohol problems, which would relate to increased IPV perpetration (i.e., psychological aggression and physical assault).

ASPD traits would relate to low distress tolerance, which would relate to increased IPV perpetration (i.e., psychological aggression and physical assault).

Method

Participants

A sample of 331 men who were arrested for domestic violence and court-ordered to attend BIPs in Rhode Island were recruited. Participant mean age was 33.43 (SD = 11.43) years old. The majority of the sample identified as Caucasian (64%), followed by Hispanic/Latino (13.3%), African American/Non-Hispanic (10%), “Other” (7.9%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (3.1%), and Asian or Pacific Islander (1.4%). The distribution of employment status was as follows: employed (53.4%), unemployed and looking for work (29.5%), unable to work (9.9%), retired (2.5%), unemployed and not looking for work (1.9%), student (1.7%), homemaker (.8%), and unreported (.3%). The mean income was $27,520 (SD = $39,999). The mean relationship length was 4.76 years (SD = 6.90).

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants reported demographic information including age, gender, employment status, race/ethnicity, relationship length, income, and number of BIP sessions completed.

Alcohol Problems

The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ; Zimmerman, 2002; Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001) alcohol abuse/dependence disorder subscale was used to assess alcohol problems during the 12 months prior to BIP entry. The PDSQ screens for Axis I disorders from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV-TR (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The alcohol abuse/dependence disorder subscale consists of 6 yes-no items, with scores ranging from 0 to 6; higher scores are indicative of more problems related to alcohol use. The PDSQ alcohol abuse/dependence disorder subscale has good internal consistency (α = .87) and is considered a valid measure of alcohol problems (Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001). The PDSQ alcohol abuse/dependence disorder subscale was previously used within offender populations (Shorey, Febres, Brasfield, & Stuart, 2012) and demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (α = .87).

Antisocial Personality Traits

The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4) Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) Scale (Hyler, 2004) assessed self-reported ASPD traits. The PDQ-4 ASPD scale consists of 22 true-false, self-report items designed to closely mirror criteria for ASPD reported in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Scores may be computed as continuous or categorical variables. The PDQ-4 was used to assess dimensions of ASPD traits rather than to diagnose participants. Therefore, continuous scores were used for the present study by summing participants’ responses to items on the ASPD subscale such that higher scores represent higher self-reported ASPD traits. Possible scores range from 0 to 8 because 14 of the 22 items assess for the presence of conduct disorder. Eight items assessed adult criteria for ASPD, including the presence of conduct disorder (i.e., 1 point) derived from the 14 conduct disorder items. The PDQ-4 ASPD subscale is considered a reliable and valid measure of antisocial traits (Hyler, 204). The PDQ-4 ASPD subscale demonstrated good psychometric properties in offender populations (Guy, Poythress, Douglas, Skeem, & Edens, 2008) and demonstrated good internal consistency in the present sample (α = .90).

IPV Perpetration

Participants completed the 20 perpetration items of the Psychological Aggression (e.g., “I insulted or swore at my partner”) and Physical Assault (e.g., “I pushed or shoved my partner”) subscales of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003) to assess IPV perpetration in the 12 months prior to BIP entry. Responses to the items ranged from 0 (this never happened) to 6 (more than 20 times). Total subscale scores were calculated by adding the midpoint for each item response (e.g., a “4” for the response “3–5 times”), with higher scores representing more frequent IPV perpetration. Previous studies indicate that the psychological aggression and physical assault subscales of the CTS2 are valid measures of IPV, have adequate internal consistency, and are widely used as measures of IPV perpetration in offender samples (Straus et al., 1996; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). The physical assault (α = .88) and psychological aggression (α = .82) subscales demonstrated good reliability in the present study.

Distress Tolerance

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005) was used to assess perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress (e.g., “I can't handle being distressed or upset”). The DTS consists of 15 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) with higher scores indicating a higher ability to tolerate distress. The DTS demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .93) in the current sample as well as good reliability (α = .89) and validity within treatment-seeking populations (Simons & Gaher, 2005).

Procedure

The institutional review board of the last author approved the procedures for the study. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study prior to completing paper-and-pencil questionnaires in small groups during regularly scheduled BIP sessions; no compensation was provided. Each BIP site administered forty-hour, open-enrollment group interventions with similar intervention content. All questionnaire responses were confidential and not shared with BIP facilitators or anyone within the criminal justice system. Participants were asked to respond to the items based on the 12 months prior to their first BIP session. Prior to data collection, participants completed an average of 10.80 (SD = 7.40) BIP sessions. Number of BIP sessions attended did not significantly relate to any study variables.

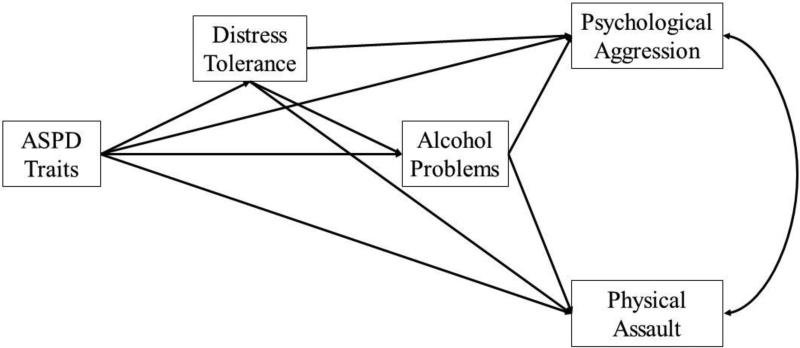

Data Analytic Strategy

First, descriptive and correlational analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 21.0. Structural equation models were estimated in Mplus Version 6.12 to test the study hypotheses. Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used to handle missing data. FIML has been shown to provide more efficient and less biased estimates than alternative strategies such as pairwise or listwise deletion (Enders, 2010; Kline, 2010). Maximum likelihood estimation was also used to account for study variables being non-normally distributed (i.e., physical assault) as this estimate is robust to issues of non-normality (Kline, 2010). Path analysis allows a series of structural regression equations to be analyzed simultaneously. The path model illustrated in Figure 1 was created by regressing IPV perpetration (i.e., psychological aggression and physical assault) on alcohol problems, distress tolerance and ASPD trait scores simultaneously; psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration were examined as separate outcome variables while controlling for their bivariate relation. Although many studies using path analyses seek to identify the best model to fit their data, the current study sought only to test the relations between ASPD traits, distress tolerance, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration variables. Therefore, a fully saturated (i.e., zero degrees of freedom) model consisting of 18 parameters was used to test for indirect effects of ASPD traits on IPV perpetration (i.e., physical assault and psychological aggression) through distress tolerance and alcohol problems (see Figure 1). Since all possible paths are tested, fully saturated models always produce a perfect fit to the data (Kline, 2010). Thus, model fit indices were neither examined nor reported in the current study.

Figure 1.

Predicted paths from antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) traits to psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration through distress tolerance and alcohol problems controlling for the relation between psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration.

Next, the bias-corrected bootstrap method procedure was used to test whether ASPD traits were indirectly associated with IPV perpetration through distress tolerance and alcohol problems, controlling for the bivariate relation between psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration. Because normal distributions are rare in small to moderate sample sizes (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004), bootstrapping resampling allows for a more accurate estimate of indirect effects without relying on the assumption of a normal distribution (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). As described by MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004), bias-corrected confidence intervals provide more accurate weight between Type I and Type II errors and a more precise assessment of indirect effects than traditional tests of mediation (e.g., Sobel test; Sobel, 1982). Thus, 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals were used to examine the significance of indirect effects. According to this method, an indirect effect is statistically significant if the value of zero is not included in the bias-corrected confidence interval.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between the non-transformed study variables are shown in Table 1. We first examined bivariate correlations between all of the study variables to determine if distress tolerance related to ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and both psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration. As indicated in Table 1, distress tolerance negatively related to ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and both psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration. ASPD traits positively related to alcohol problems and both psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration. Alcohol problems positively related to psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration. Bidirectional IPV perpetration (i.e., at least one act of either psychological aggression or physical assault perpetration was endorsed, and at least one act of either psychological aggression or physical assault victimization was endorsed) was endorsed by 99.7% of the sample.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ASPD Traits | - | −.29** | .23** | .13* | .24** |

| 2. Distress Tolerance | - | −.40** | −.15** | −.16** | |

| 3. Alcohol Problems | - | .26** | .15** | ||

| 4. Psychological Aggression | - | .61** | |||

| 5. Physical Assault | - | ||||

| Mean | 4.39 | 44.67 | 1.42 | 36.36 | 10.18 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.81 | 13.70 | 1.78 | 36.82 | 24.66 |

Note. ASPD = antisocial personality disorder.

p < .01

p < .05.

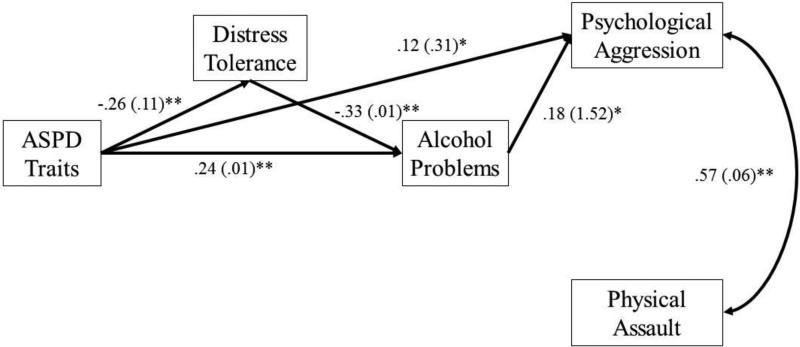

Path Models

Results of path analyses are displayed in Figure 2. Results revealed that ASPD traits and alcohol problems significantly related to psychological aggression perpetration. Distress tolerance and ASPD traits were significantly correlated with alcohol problems. Distress tolerance significantly correlated with ASPD traits.

Figure 2.

The direct and indirect effects of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) traits on psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration through distress tolerance and alcohol problems, controlling for the relation between psychological aggression and physical assault. **p < .001, * p < .05.

Hypothesis 1 was partially supported. Test for indirect effects revealed a two-chain indirect path such that men's ASPD traits associated with psychological aggression perpetration through distress tolerance and alcohol problems (B = .07, 95% CI = .03 to .11). That is, ASPD traits associated with low distress tolerance, low distress tolerance associated with increased alcohol problems, and increased alcohol problems related to more frequent psychological aggression perpetration. A second path emerged by which ASPD traits associated with more psychological aggression perpetration through alcohol problems (B = .04, 95% CI = .01 to .08). That is, ASPD traits associated with increased alcohol problems, and alcohol problems associated with more frequent psychological aggression perpetration. In a third path, ASPD traits predicted psychological aggression, in the presence of paths two and from distress tolerance and alcohol problems. ASPD traits did not relate to increased physical assault perpetration through distress tolerance and alcohol problems while controlling for the relation between psychological aggression and physical assault perpetration.

Hypothesis 2 was not supported. ASPD traits did not associate with increased IPV perpetration (i.e., psychological aggression or physical assault) through distress tolerance in the presence of paths to and from alcohol problems.

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine distress tolerance as an underlying mechanism of the relation between ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration among men arrested for domestic violence. Results of the present study support multiple pathways from ASPD traits to IPV perpetration, which included both distress tolerance and alcohol problems.

These findings support previous research highlighting the need to examine emotion regulation constructs (i.e., distress tolerance) in the context of IPV perpetration, particularly as they relate to alcohol use problems (Ortiz et al., 2015). In partial support of Hypothesis 1, our findings indicate that low distress tolerance may account for psychological aggression perpetration, but not physical assault perpetration, observed in men who endorse ASPD traits due, in part, to such individuals’ propensity to engage in problematic alcohol use. Individuals with ASPD traits endorse lower levels of distress tolerance than do individuals without ASPD traits (Cummings et al., 2013; Sargeant et al., 2011), and are thus believed to have diminished capacity to select adaptive regulatory behaviors. It therefore follows that such individuals would be at increased risk for using alcohol as a coping strategy and responding aggressively when faced with aversive affect.

Contrary to Hypothesis 2, distress tolerance did not account for the link between ASPD traits and IPV perpetration (i.e., psychological aggression or physical assault) while controlling for the influence of alcohol problems. While preliminary, these results suggest that, for men with ASPD traits, emotion regulation constructs (i.e., distress tolerance) may facilitate decreased IPV perpetration, but only as they relate to decreased alcohol problems. It is plausible that alcohol problems increased participants’ susceptibility to involvement in antisocial activities, including IPV perpetration, thereby reducing the likelihood that distress tolerance would account for the relationship. Longitudinal data are needed to examine this possibility.

Because previous research suggests psychological aggression predicts physical assault perpetration (Stuart et al., 2006), it is possible that psychological aggression mediates the relation between alcohol problems and physical assault perpetration. This hypothesis is further supported by the current findings which indicated that, controlling for the influence of all other study variables, psychological aggression is the only significant correlate of physical assault perpetration. Longitudinal research is needed to investigate this theoretical supposition among a sample of men arrested for domestic violence. Alternatively, it is plausible that other dyadic mechanisms better account for the tendency of some men with ASPD traits to engage in physical assault. Although 99.7% of men in the current sample endorsed bidirectional IPV perpetration, partner reports of IPV perpetration would elucidate the nature of violence within the dyad.

Findings from the present study are consistent with previous theory and research indicating alcohol problems are strong, but not necessary, predictors of IPV perpetration (Ortiz et al., 2015; Stuart et al., 2006). Alcohol problems may increase the risk of IPV perpetration among some, but not all, men arrested for domestic violence. That distress tolerance only partially mediated the relation between ASPD traits and IPV perpetration suggests that other mechanisms also account for the relation between ASPD traits and IPV perpetration. Indeed, previous research found that genetic variables, parental discipline, hostile biases, parental alcohol use, and deficient cognitive executive brain functioning related to ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV perpetration (Ali & Naylor, 2013; Moeller & Dougherty, 2001; Stuart et al., 2014). Interventions aimed to reduce both alcohol problems and IPV perpetration among offenders would benefit from longitudinal research methods exploring these and other potential underlying mechanisms.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, there are several limitations to the present study that should be considered when interpreting results. First, our sample was comprised of primarily Caucasian men, which limits generalizability to more diverse samples. Future research should examine whether these findings are supported within a more diverse sample that includes women. Second, the cross-sectional nature of our study design prevents conclusions regarding the directionality and causality of study variables. Though theory and research suggest that ASPD traits precede problems associated with alcohol use (Cho et al., 2014), and alcohol problems lead to IPV perpetration (Stuart et al., 2006), it is possible that alcohol problems increased men's engagement in antisocial activities, including IPV perpetration (Cho et al., 2014). Alternatively, it is possible that excessive alcohol use over time results in decreased executive functioning (Thoma et al., 2011), thereby leading to lower distress tolerance. Similarly, the direction of the relation between ASPD traits and distress tolerance remains unclear (Cummings et al., 2013), and the presence of aversive affect or alcohol use at the time of IPV perpetration could not be determined due to the cross-sectional nature of our study. Longitudinal data using structured, clinical interviews are needed to better understand the role of distress tolerance in the etiology of ASPD traits and alcohol problems among men who perpetrate IPV. Relatedly, future research should consider using multiple methods of assessment to explore these constructs. Third, use of retrospective, self-report measures within a sample of men arrested and undergoing treatment in BIPs increases the likelihood that our findings are influenced by social desirability. Finally, additional research is needed to explore other variables (e.g., negative affect, impulsivity, victimization, and partner variables) that may influence results.

Research Implications

In addition to improving these limitations, future research should investigate the development of distress tolerance skills in relation to ASPD traits, alcohol problems, and IPV. Although Cummings and colleagues (2013) found low distress tolerance co-occurred with behaviors predictive of ASPD, no research has longitudinally explored the development of low distress tolerance among adults with ASPD traits. Understanding how distress tolerance develops, and whether or not it protects against behaviors known to increase the likelihood of IPV perpetration (e.g., problematic alcohol use) would inform IPV prevention efforts.

Furthermore, a growing body of research has investigated emotion regulation more broadly in relation to IPV perpetration. However, only one study examined the relation between distress tolerance and IPV perpetration (Shorey et al., 2015), and these data were gathered by employing cross-sectional, self-report methodology. Results of the present study, paired with existing empirical and theoretical evidence, point to the need to examine proximal relations between negative affect, specific emotion regulation components (e.g., distress tolerance), problematic alcohol use, and IPV perpetration within an offender sample. Specifically, use of more event-level research methods (e.g., daily diary research) is an important direction for future research as it allows for examination of alcohol use, IPV, and affective constructs within both members of the dyad during a violent incident. By developing a better understanding of the conditions under which IPV occurs, and protective factors that interfere with such conditions, more efficacious intervention programs may emerge for men arrested for domestic violence.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Despite the consistent support for the link between aversive internal experiences and IPV perpetration across multiple theoretical models of IPV, many states prohibit the use of emotion regulation techniques in BIPs due, in part, to mandated adherence to the power-and-control-based patriarchal ideology model (Birkley & Eckhardt, 2015; Rosenbaum & Kunkel, 2009). The limited efficacy of existing state-mandated BIPs in reducing recidivism suggests a need to consider empirically-supported intervention targets (Stuart, Temple, & Moore, 2007). Our findings, combined with existing conceptual models of IPV perpetration (e.g., Bell & Naugle, 2008; Stuart et al., 2006), support the need for IPV intervention efforts to target both alcohol problems and emotion regulation skills, specifically distress tolerance, with men arrested for domestic violence. It is plausible that bolstering distress tolerance among individuals with ASPD traits may reduce the likelihood that such individuals would engage in maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as alcohol use and IPV perpetration, in the presence of aversive affect. Unfortunately, researchers have yet to examine the efficacy of emotion regulation components, including distress tolerance, within treatments for IPV offenders (Birkley & Eckhardt, 2015).

Notably, several intervention approaches targeting distress tolerance (e.g., Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy) demonstrated efficacy in reducing both alcohol use and aggression (Frazier & Vela, 2014; Hsu, Collins, & Marlatt, 2012; Wupperman, Cohen, Haller, Flomm, Litt, & Rounsaville, 2015; Zarling, Lawrence, & Marchman, 2015). These mindfulness-based treatment approaches foster awareness and acceptance of internal and external experiences such that individuals are more willing to approach, and thus habituate to, aversive affect (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). Similarly, an initial examination of a brief distress tolerance intervention demonstrated efficacy in improving distress tolerance among patients in a residential substance use treatment facility (Bornovalova, Gratz, Daughters, Hunt, & Lejuez, 2012). Each of these approaches include distress tolerance as a therapeutic component, which may offer critical insights in the development of future IPV intervention packages aiming to increase emotion regulation skills and/or reduce alcohol use. Thus, there is a clear need for researchers to determine whether treatment approaches aimed to increase distress tolerance would correspond to reductions in men's alcohol problems and IPV perpetration within an offender sample.

Conclusion

The present study extended previous research by examining multiple pathways from men's ASPD traits to IPV perpetration, which included distress tolerance and alcohol problems. Our results support a model consisting of three pathways from ASPD traits to psychological aggression perpetration among men arrested for domestic violence. In one path, distress tolerance and alcohol problems explained the relation between ASPD traits and psychological aggression perpetration. A second path emerged in which ASPD traits associated with increased alcohol problems, which related to increased psychological aggression. In a third path, ASPD traits related to psychological aggression perpetration in the presence of paths to and from distress tolerance and alcohol problems. Controlling for psychological aggression perpetration, neither distress tolerance nor alcohol problems explained the relation between ASPD traits and physical assault perpetration. These findings contribute to the substantial body of research highlighting the need for BIPs to incorporate skills to facilitate emotion regulation and reduce problematic alcohol use, especially within offender populations that endorse ASPD traits.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grant K24AA019707 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awarded to the last author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ali B, Ryan JS, Beck KH, Daughters SB. Trait aggression and problematic alcohol use among college students: The moderating effect of distress tolerance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(12):2138–2144. doi: 10.1111/acer.12198. doi: 10.1111/acer.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali PA, Naylor PB. Intimate partner violence: A narrative review of the biological and psychological explanations for its causation. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18(3):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2013.01.003. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkley EL, Eckhardt CI. Anger, hostility, internalizing negative emotions, and intimate partner violence perpetration: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;37:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC. Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2011;5(5):428–439. doi: 10.1177/1559827611410265. [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Hunt ED, Lejuez CW. Initial RCT of a distress tolerance treatment for individuals with substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;122(1-2):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.012. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18(4):211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cho SB, Heron J, Aliev F, Salvatore JE, Lewis G, Macleod J, Hickman M, Maughan B, Kendler KS, Dick DM. Directional relationships between alcohol use and antisocial behavior across adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(7):2024–2033. doi: 10.1111/acer.12446. doi: 10.1111/acer.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Mitchel MK, Teti LOD. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:73–73. 73–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings Jr., Bornovalova MA, Ojanen T, Hunt E, Macpherson L, Lejuez C. Time doesn't change everything: The longitudinal course of distress tolerance and its relationship with externalizing and internalizing symptoms during early adolescence. Journal Of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(5):735–748. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9704-x. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9704-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Sargeant MN, Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Lejuez CW. The relationship between distress tolerance and antisocial personality disorder among male inner-city treatment seeking substance users. Journal of personality disorders. 2008;22(5):509. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.5.509. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.5.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI. Effects of alcohol intoxication on anger experience and expression among partner assaultive men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):61–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier SN, Vela J. Dialectical behavior therapy for the treatment of anger and aggressive behavior: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19(2):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.02.001. [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy LS, Poythress NG, Douglas KS, Skeem JL, Edens JF. Correspondence between self-report and interview-based assessments of Antisocial Personality Disorder. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:47–54. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.1.47. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.20.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Jordan CE. Intimate partner and sexual violence research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(3):149–158. doi: 10.1177/1524838014520723. doi: 10.1177/1524838014520723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Meehan JC, Herron K, Rehman U, Stuart GL. Testing the Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) Batterer Typology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(6):1000–1019. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1000. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SH, Collins SE, Marlatt GA. Examining psychometric properties of distress tolerance and its moderation of mindfulness-based relapse prevention effects on alcohol and other drug use outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;38(3):1852–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.002. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyler SE. The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4+ New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(4):576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbestael J, Cima M, Lemmens The relationship between personality disorder traits and reactive versus proactive motivation for aggression. Psychiatry Research. 2015;229(1-2):155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean JC, French MT. Personality disorders, alcohol use, and alcohol misuse. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;120:286–300. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.029. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz E, Shorey RC, Cornelius TL. An examination of emotion regulation and alcohol use as risk factors for female-perpetrated dating violence. Violence and Victims. 2015;30(3):417–431. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum A, Kunkel T. Group interventions for intimate partner violence. In: O'Leary KD, Woodin EM, editors. Understanding Psychological and Physical Aggression in Couples: Existing Evidence and Clinical Implications. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant M, Daughters SB, Curtin J, Schuster R, Lejuez CW. Unique roles of Antisocial Personality Disorder and psychopathic traits in distress tolerance. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(4):987–992. doi: 10.1037/a0024161. doi: 10.1037/a0024161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Elmquist J, Strauss C, Anderson SE, Stuart GL. Research reactions following participation in intimate partner violence research: An examination with men in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0886260515584345. doi: 10.1177/0886260515584345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Febres J, Brasfield H, Stuart GL. The prevalence of mental health problems in men arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27(8):741–748. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9463-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Gaher R. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and Validation of a Self-Report Measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. American Sociological Association; Washington, DC: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sprunger JG, Eckhardt CI, Parrott DJ. Anger, problematic alcohol use, and intimate partner violence victimisation and perpetration. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2015;25:273–286. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2). Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales Handbook. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2006;67(1):102. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, McGeary J, Shorey RC, Knopik V, Beaucage K, Temple JR. Genetic associations with intimate partner violence in a sample of hazardous drinking men in batterer intervention programs. Violence Against Women. 2014;20:385–400. doi: 10.1177/1077801214528587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Temple JR, Moore TM. Improving batterer intervention programs through theory-based research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(5):560–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma RJ, Monnig MA, Lysne PA, Ruhl DA, Pommy JA, Bogenschultz M, Tonigan JS, Yeo RA. Adolescent substance abuse: The effects of alcohol and marijuana on neuropsychological performance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa EC, Hammett JF. The effect of gender and perpetrator–victim role on mental health outcomes and risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence. 2016;31(7):1184–1207. doi: 10.1177/0886260514564163. doi: 10.1177/0886260514564163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wupperman P, Cohen MG, Haller DL, Flom P, Litt LC, Rounsaville BJ. Mindfulness and modification therapy for behavioral dysregulation: A comparison trial focused on substane use and aggression. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2015;71(10):964–978. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22213. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarling A, Lawrence E, Marchman J. A randomized controlled trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for aggressive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):199–212. doi: 10.1037/a0037946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The Psychiatric Disgnostic Screening Questionnaire: Development, reliability, and validity. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:175–189. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.23126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]