Abstract

This study investigated longitudinal associations between adolescents’ technology-based communication and the development of interpersonal competencies within romantic relationships. A school-based sample of 487 adolescents (58% girls; Mage = 14.1) participated at two time points, one year apart. Participants reported (1) proportions of daily communication with romantic partners via traditional modes (in person, on the phone) versus technological modes (text messaging, social networking sites) and (2) competence in the romantic relationship skill domains of negative assertion and conflict management. Results of cross-lagged panel models indicated that adolescents who engaged in greater proportions of technology-based communication with romantic partners reported lower levels of interpersonal competencies one year later, but not vice versa; associations were particularly strong for boys.

The ubiquitous use of technology among youth provides a new context for the establishment and maintenance of intimate relationships in adolescence (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008). Over 89% of adolescents report using social networking sites (Lenhart, 2015) and 92% report text messaging with their romantic partners (Lenhart, Smith, & Anderson, 2015). Further, it is common for adolescents to use technology to resolve arguments and discuss sensitive family or health-related issues with romantic partners (Lenhart et al., 2015; Widman, Nesi, Choukas-Bradley, & Prinstein, 2014). Although it is well established that romantic relationships provide a critical context for adolescents’ development of social competence (Collins & Steinberg, 2006), little is known regarding how technology-based communication may affect this process.

Social competence is a multidimensional construct, with two particular domains that may be important to adolescent romantic relationships: negative assertion (the ability to assert displeasure with others or stand up for oneself) and conflict management (the ability to work through disagreements and solve problems; Buhrmester, Furman, Wittenberg, & Reis, 1988). These skills are particularly salient within the context of romantic relationships, where they influence relationship satisfaction, negotiation of autonomy and general socioemotional competence (Collins, 2003).

The rising popularity of computer-mediated communication tools (e.g., texting, social media) has shifted the way youth communicate with romantic partners (Lenhart et al., 2015). Cues-filtered-out theories suggest that some of these tools contain fewer nonverbal cues than traditional interactions; this may make technology-based communication less “rich” (Walther, 2011). On the one hand, technologies with fewer cues may provide a safe space for adolescents to practice self-disclosure and communicate asynchronously (Koutamanis, Vossen, Peter, & Valkenburg, 2013), thus providing opportunities for greater relationship maintenance, self-disclosure, and intimacy (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). On the other hand, these technologies may result in lower quality interactions. Indeed, some work suggests that technology-based communication is associated with less warmth and affection, fewer expressed affiliation cues, and lower feelings of bonding (Sherman, Michikyan, & Greenfield, 2013; Subrahmanyam & Šmahel, 2011).

While technology may simply supplement traditional forms of interaction (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007), in some situations technology may provide a substitute for youths’ traditional communication (Szwedo, Mikami, & Allen, 2012). If technology-based communication is replacing traditional communication for some adolescents, and some technological tools lack the “richness” necessary for practicing complex romantic relationship interactions (Sherman et al., 2013; Walther, 2011), higher proportions of technology-mediated communication could adversely affect young people’s social skill development and relationship satisfaction (Luo, 2014). This may be particularly true of high-conflict interactions, wherein more interpersonal cues are required to express and manage negative affect (Burge & Tatar, 2009). However, research has yet to examine the role of technology-mediated communication in the romantic relationships of middle or high school–aged adolescents, or the role such communication may play over time.

Additionally, little is known about potential gender differences in the role of technology in the development of interpersonal competencies. There are known gender differences in the frequency of technology use, with adolescent girls reporting more social media use and texting than boys (Lenhart, 2015), but such research has not clarified how technology use differentially affects girls and boys. A separate, long-standing line of work indicates that relationship skills differ by gender, with girls reporting higher levels of intimacy, self-disclosure, and positive conflict–resolution strategies within same-gender friendships beginning in childhood (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Girls may thus enter romantic relationships better prepared for handling intimacy and conflict (Maccoby, 1998). It is possible that increases in technology-based communication are more detrimental to boys’ development of romantic relationship competencies, as girls may have developed stronger foundations of relationship skills through childhood friendships.

This study utilized a longitudinal cross-lagged design to examine associations between adolescents’ communication patterns and the development of interpersonal competencies within romantic relationships over 1 year. It was hypothesized that greater levels of technology-based communication versus traditional forms of communication with romantic partners would be negatively associated with interpersonal competencies over time. It also was hypothesized that this association would be stronger for boys.

METHODS

Participants

This study included 487 participants (58.0% girls; ages 13–16; Mage = 14.1; 48.5% White/Caucasian, 23.8% Hispanic/Latino, 20.6% African American/Black, 7.1% other ethnicities). Participants were 85.9% heterosexual, 0.6% gay/lesbian, 5.5% bisexual, and 8.0% unsure/other; for multiple group analyses, both heterosexual and sexual minority youth were present in each gender group.

All seventh and eighth grade students from three rural, low-income schools (n = 1,463) were recruited for a study of peer relations and health risk behaviors. Consent forms were returned by 1,205 families (82.4%), with 900 granting consent for participation (74.7%). Baseline data were collected from 868 students (32 consented adolescents had moved, were absent, or declined participation). The current study utilizes data from the 1-year (T1) and 2-year (T2) follow-ups, when relevant measures were administered. Retention exceeded 88% at T1 (n = 790) and T2 (n = 772).

Only participants who reported having had a dating partner within the past year at both time points were included in analyses. A dating partner was defined as “a boyfriend/girlfriend or someone you like ‘more than friends’ who you have ‘talked to’ or ‘hung out with’.” This definition was developed based on past literature (e.g., Furman & Hand, 2006), as well as pilot testing and focus groups. Of the 734 participants who participated at both T1 and T2, 66.5% (n = 488) reported having dating partners at both waves. One participant was missing data on all other study variables. Thus, the final sample included 487 participants.

No significant differences in age or ethnicity were found between these participants and those who reported no romantic relationships at either wave (n = 233). Girls were more likely than boys to report relationships at both time points (χ2 = 6.49, p < .05). Adolescents’ proportion of engagement in technology-based communication at T1 did not predict whether they reported a relationship at T2.

Procedure

Following informed assent procedures, surveys were administered in classrooms via computer-assisted self-interviews. Each participant received a $10 gift card at both time points. All measures were collected at both waves.

Measures

Proportion of technology-based versus traditional communication with partner

Participants were oriented to the construct of technology-based communication, with technology defined as “texting, Facebook, and other social media (e.g., Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Tumblr).” Relative frequencies of the use of technology, versus traditional forms of communication, were assessed by asking, “How much do you communicate with your dating partners using your voice (in person or phone call) versus using technology on a typical day?” These definitions of technology and traditional communication were chosen based on cues-filtered-out approaches (Walther, 2011). Specifically, phone and in-person communication are similar in nature given their allowance for immediate feedback and multiple vocally based interpersonal cues, compared to text messaging and social networking sites. Responses were indicated on a 9-point scale (1 = I communicate with my romantic partners mostly in person/on phone calls, 5 = About half in person/on phone calls and about half using technology, and 9 = I communicate with my romantic partners mostly using technology. We rarely communicate in person/on phone calls). Higher scores indicated higher proportions of technology-based communication relative to traditional communication. This measure was developed through a focus group and two pilot samples of 437 high school students.

Interpersonal competencies within romantic relationships

The Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire (ICQ; Buhrmester et al., 1988) was used to assess negative assertion (e.g., “Turning down a request by your dating partner that is unreasonable”; α = .84 and .91 at T1 and T2, respectively) and conflict management (e.g., “Admitting that you might be wrong when a disagreement with your dating partner begins to build into a serious fight”; α = .83 and .90) with adolescents’ current or most recent dating partner. Responses were indicated on a 5-point scale (1 = I am very bad at this, 3 = I am okay at this, and 5 = I am very good at this). Several items were reworded to accommodate the sample’s reading level. Each subscale contained eight items; however, one item was dropped from each scale due to low factor loadings.

Analysis Plan

Hypotheses were examined within a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework in Mplus 7.0. Negative assertion and conflict management at T1 and T2 were estimated as latent variables by creating three parcels of items for each variable, with items randomly assigned to parcels. Using parcels allowed for increased parsimony, fewer chances for correlated residuals or dual loadings, and reductions in sampling error (MacCallum, Widaman, Zhang, & Hong, 1999). A confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated the unidimensionality of each variable.

Cross-lagged panel models were used, providing a useful framework for testing the strength of temporal relations between variables collected through longitudinal, nonexperimental designs (Finkel, 1995). Four separate models were specified as follows: (1) a baseline model with only autoregressive paths (i.e., paths from negative assertion at T1 to T2, conflict management at T1 to T2, and proportions of technology-based communication at T1 to T2); (2) a model with these autoregressive effects and paths from T1 proportions of technology-based communication to T2 negative assertion and conflict management; (3) a model with the autoregressive effects and paths from T1 negative assertion and conflict management to proportions of T2 technology-based communication; and (4) a fully cross-lagged model with autoregressive effects and all T1 variables predicting all others at T2. In these models, all T1 predictors and T2 error terms were correlated with one another (Martens & Haase, 2006). Models were compared using chi-square difference tests to determine the optimally fitting model (Bollen & Curran, 2006). Moderation by gender was then tested using a multiple group SEM.

RESULTS

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics examined patterns of technology-based versus traditional forms of communication and gender differences in those patterns (Table 1). Correlations between all variables were also calculated (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Full Sample | Girls | Boys | Gender Comparison t (df) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| M (SD) | N | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | ||

| Time 1 variables | |||||||

| Negative assertion | 3.67 (0.82) | 484 | 3.75 (0.81) | 279 | 3.58 (0.83) | 205 | 2.20 (482)* |

| Conflict management | 3.61 (0.81) | 483 | 3.46 (0.80) | 279 | 3.83 (0.77) | 204 | 35.08 (481)*** |

| Proportions of technology-based romantic partner communicationa | 4.85 (2.32) | 449 | 4.83 (2.40) | 264 | 4.89 (2.25) | 185 | 30.24 (447) |

| Time 2 variables | |||||||

| Negative assertion | 3.82 (0.78) | 483 | 3.81 (0.79) | 280 | 3.28 (0.93) | 203 | 6.73 (481)*** |

| Conflict management | 3.37 (0.89) | 483 | 3.40 (0.82) | 280 | 3.34 (0.98) | 203 | 0.69 (481) |

| Proportions of technology-based romantic partner communicationa | 5.04 (2.11) | 485 | 5.02 (2.19) | 281 | 5.05 (2.00) | 204 | 30.15 (483) |

Note.

Higher scores indicate greater proportions of technology-based communication (texting, social media) relative to traditional communication (in person, phone calls) with romantic partners.

p < .05;

p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Associations by Gender

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 negative assertion | – | .33*** | .10 | .47*** | .24*** | −.09 |

| 2. T1 conflict management | .38*** | – | .02 | .14* | .44*** | −.05 |

| 3. T1 proportions of technology-based romantic partner communicationa | .14 | −.08 | – | .01 | −.00 | .13* |

| 4. T2 negative assertion | .30*** | .09 | −.15* | – | .53** | −.09 |

| 5. T2 conflict management | .06 | .27*** | −.27*** | .65*** | – | −.02 |

| 6. T2 proportions of technology-based romantic partner communicationa | .02 | .15* | .09 | −.04 | .01 | – |

Note. Results for girls reported above the diagonal. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

Higher scores indicate greater proportions of technology-based communication (texting, social media) relative to traditional communication (in person, phone calls) with romantic partners.

p< .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Roughly one-third of participants (34.9%) reported that, on a typical day, they communicated with their dating partners approximately half the time using technology and half the time through traditional communication forms (in person or phone calls), another third (32.3%) reported using primarily traditional forms, and the remaining third (32.8%) reported that the majority of their communication with partners occurred via technology.

Associations Among Technology-Based Communication, Negative Assertion, and Conflict Management

Four cross-lagged panel models were constructed (see Table 3). Chi-square difference testing indicated that Model 2 was the optimally fitting and most parsimonious model; the added constraints of this model over Model 1 resulted in a significant improvement in fit, while those of Model 3 did not. In addition, Model 4 did not provide a significant improvement in fit over Model 2, suggesting that the more parsimonious model (Model 2) should be retained. Paths from T1 negative assertion and conflict management to T2 proportions of technology-based communication were not significant in any models.

TABLE 3.

Fit Statistics for Four Competing Cross-Lagged Panel Design Models

| Model | χ2 | df | p-value | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Autoregressive | 101.88 | 64 | .002 | .04 | .05 | .99 | .98 |

| Model 2: T1 communication?T2 interpersonal competence | 91.80 | 62 | .008 | .03 | .04 | .99 | .99 |

| Model 3: T1 interpersonal competence?T2 communication | 100.65 | 62 | .001 | .04 | .05 | .99 | .98 |

| Model 4: Fully cross-lagged | 90.57 | 60 | .007 | .03 | .04 | .99 | .99 |

Note. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2. Chi-square difference tests indicate that Model 2 is the optimally fitting model. Communication refers to proportions of technology-based romantic partner communication.

Tests of Measurement Invariance and Gender Moderation

First, measurement invariance was established across gender groups. Tests of measurement invariance revealed consistent factor structure, and no statistical benefit when allowing factor loadings, Δχ2(8) = 7.337, p = .50, and all but one of the indicator intercepts, Δχ2(6) = 11.43, p = .08, to vary across gender. Thus, partial strong invariance was established, indicating that latent constructs were assessed using the same metric across groups. This allowed for meaningful gender comparisons in subsequent analyses.

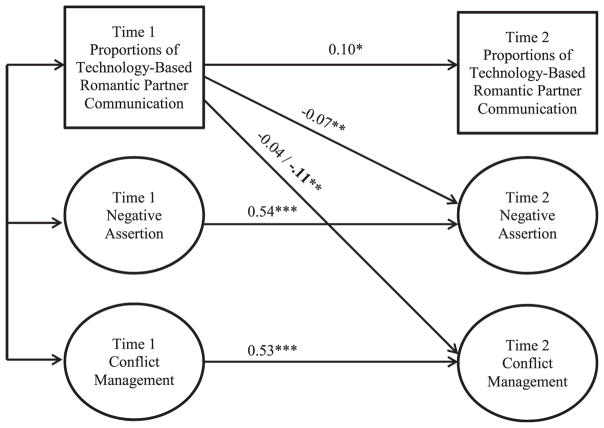

Initial fit for the structural model was good: χ2(161) = 240.43, p < .001, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.97, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.08. Chi-square difference tests indicated a marginally significant gender interaction for the association between T1 technology-based communication and T2 conflict management, Δχ2(1) = 3.36, p = .07; this path was thus left free to vary across groups. Standardized path coefficients in the final model revealed that greater proportions of technology-based communication with romantic partners, relative to traditional communication at T1, were associated with lower levels of T2 negative assertion for both genders, and with lower levels of T2 conflict management for boys only (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Cross-lagged panel model (Model 2) for the relationship between technology-based versus traditional romantic partner communication and interpersonal competencies (conflict management and negative assertion), with path coefficients. Correlations between error terms for Time 2 variables not shown. For path moderated by gender, coefficient for boys in bold. Indicators for latent variables not included in figure. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated associations between adolescents’ technology-based communication and the development of interpersonal competencies within romantic relationships and examined gender differences in these associations. Given that adolescents’ technology-based communication within romantic relationships is an emerging field of research and that this study is the first to examine these associations, results should be considered preliminary. Findings suggest that adolescents who engaged in proportionally more technology-based versus traditional communication with partners exhibited lower levels of specific interpersonal competencies (negative assertion and conflict management) within romantic relationships one year later; this association was somewhat stronger for boys.

Notably, engagement in greater proportions of technology-based communication preceded, rather than followed, lower competencies in these areas. Poorer self-reported interpersonal skills did not predict later engagement in technology-based communication. Technology-based interactions may provide a qualitatively different communication experience, through which adolescents lack optimal opportunities to learn or practice complex social skills, such as negative assertion and conflict management.

These preliminary findings are consistent with prior work demonstrating concurrent associations among high proportions of technology-based communication, less satisfaction, and higher avoidance in young adults’ romantic relationships (Luo, 2014). However, some past studies have found positive associations, including between more social media use and higher levels of social skills (Koutamanis et al., 2013). These mixed findings may be due to measurement differences, given that most studies (with the exception of Luo, 2014) have assessed overall frequencies, rather than proportional levels, of technology-based communication. Mixed findings may also be due to unexamined third variables (e.g., opportunity for in-person interaction, relationship duration, intimacy). Further work is needed to clarify such discrepancies.

Although both girls and boys showed similar patterns of results, technology-based communication significantly predicted conflict management deficits for boys only. Based on childhood interpersonal experiences that involve greater intimacy, self-disclosure, and conflict-mitigating strategies, girls may enter into romantic relationships better equipped with interpersonal skills (Maccoby, 1998; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Romantic relationships may provide a unique environment in which boys can develop these skills. This may be especially true for conflict management, as romantic relationships provide an important context for boys’ development of compromise strategies, a departure from the more confrontational strategies common within their same-sex friendships (Connolly & McIsaac, 2011). The use of technology-based communication in romantic relationships may limit the social “practice” of in-person conversations that is crucial for adolescent boys’ interpersonal skill development.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

Although this study is strengthened by its large, diverse sample of adolescents and longitudinal, cross-lagged research design, results should be considered preliminary given the study’s limitations. First, while this study offered a unique opportunity to investigate the specific interpersonal skills of negative assertion and conflict management, only two ICQ subscales were administered. Future research should build on these findings by investigating other social competencies (e.g., self-disclosure, emotional support) over a longer developmental period. Additionally, the measure of romantic relationships was broad. Although this definition has the benefit of being inclusive and consistent with adolescents’ concepts of relationships (Furman & Hand, 2006), some adolescents may have reported on unreciprocated relationships, which could involve higher proportions of technology-based communication. Future work should examine the role of technology within romantic relationships of varying duration, intimacy, and quality, as well as within friendships. Finally, this study used a single-item self-report measure of communication, which did not specify how adolescents should categorize newer forms of communication that blur the lines between traditional and technology-based communication (e.g., Skype and FaceTime), and which may indirectly assess total amount of communication with partners.

Future research will benefit from the development of innovative and nuanced measures of technology use, including replacing or supplementing measures of proportional communication with those that measure raw communication frequencies. Because technology-based communication can significantly differ in quality (across both individuals and forms of technology), it would also be fruitful to incorporate measures of communication quality. Future research should also examine technology-based communication among adolescents with differential in-person access to peers (e.g., rural vs. urban environments), although initial evidence suggests that these phenomena may be universal (Lenhart, 2015).

Adolescents increasingly use technological tools for communication. It is possible that adolescents are replacing traditional communication forms with this technology and thus lacking opportunities to develop essential interpersonal skills within romantic relationships. These preliminary findings highlight the importance of further investigation into associations between adolescents’ technology-based communication and development of interpersonal skills.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-MH85505 and R01-HD055342 awarded to Mitchell J. Prinstein and R00-HD075654 awarded to Laura Widman. This work was also supported in part by funding from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1144081) awarded to Jacqueline Nesi. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or NSF.

Contributor Information

Jacqueline Nesi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Laura Widman, North Carolina State University.

Sophia Choukas-Bradley, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Mitchell J. Prinstein, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. Edison, NJ: Wiley; 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W, Wittenberg MT, Reis HT. Five domains of interpersonal competence in peer relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:991–1008. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge JD, Tatar D. Affect and dyads: Conflict across different technological media. In: Harrison S, editor. Media space: 20+ years of mediated life. London, UK: Springer; 2009. pp. 123–144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.1301001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 1003–1067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, McIsaac C. Romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Underwood MK, Rosen LH, editors. Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 180–203. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SE. Causal analysis with panel data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Hand LS. The slippery nature of romantic relationships: Issues in definition and differentiation. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Risks and opportunities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 171–178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koutamanis M, Vossen HGM, Peter J, Valkenburg PM. Practice makes perfect: The longitudinal effect of adolescents’ instant messaging on their ability to initiate offline friendships. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. Teens, social media and technology overview 2015. 2015 Retrieved June 27, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/

- Lenhart A, Smith A, Anderson M. Teens, technology, and romantic relationships. 2015 Retrieved December 15, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/01/teens-technology-and-romantic-relationships/

- Luo S. Effects of texting on satisfaction in romantic relationships: The role of attachment. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;33:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Haase RF. Advanced applications of structural equation modeling in counseling psychology research. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34:878–911. doi: 10.1177/0011000005283395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential tradeoffs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman LE, Michikyan M, Greenfield PM. The effects of text, audio, video, and in-person communication on bonding between friends. Cyberpsychology. 2013;7(2) doi: 10.5817/CP2013-2-3. article 3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K, Greenfield P. Online communication and adolescent relationships. The Future of Children. 2008;18:119–146. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K, Šmahel D. Digital youth. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szwedo DE, Mikami AY, Allen JP. Social networking site use predicts changes in young adults’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22:453–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00788.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12:1169–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther JB. Theories of computer-mediated communication and interpersonal relations. In: Knapp ML, Daly JA, editors. The handbook of interpersonal communication. Vol. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. pp. 443–479. [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Nesi J, Choukas-Bradley S, Prinstein MJ. Safe sext: Adolescents’ use of technology to communicate about sexual health with dating partners. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54:612–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]