Abstract

Background

Intravenous (IV) arginine has been reported to ameliorate acute metabolic stroke symptoms in adult patients with Mitochondrial Encephalopathy with Lactic Acidosis and Stroke-like Episodes (MELAS) syndrome, where its therapeutic benefit is postulated to result from arginine acting as a nitric oxide donor to reverse vasospasm. Further, reduced plasma arginine may occur in mitochondrial disease since the biosynthesis of arginine’s precursor, citrulline, requires ATP. Metabolic strokes occur across a wide array of primary mitochondrial diseases having diverse molecular etiologies that are likely to share similar pathophysiologic mechanisms. Therefore, IV arginine has been increasingly used for the acute clinical treatment of metabolic stroke across a broad mitochondrial disease population.

Methods

We performed retrospective analysis of a large cohort of subjects who were under 18 years of age at IRB #08-6177 study enrollment and had molecularly-confirmed primary mitochondrial disease (n=71, excluding the common MELAS m.3243A>G mutation). 9 unrelated subjects in this cohort received acute arginine IV treatment for one or more stroke-like episodes (n=17 total episodes) between 2009 and 2016 at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Retrospectively reviewed data included subject genotype, clinical symptoms, age, arginine dosing, neuroimaging (if performed), prophylactic therapies, and adverse events.

Results

Genetic etiologies of subjects who presented with acute metabolic strokes included 4 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) pathogenic point mutations, 1 mtDNA deletion, and 4 nuclear gene disorders. Subject age ranged from 19 months to 23 years at the time of any metabolic stroke episode (median, 8 years). 3 subjects had recurrent stroke episodes. 70% of stroke episodes occurred in subjects on prophylactic arginine or citrulline therapy. IV arginine was initiated on initial presentation in 65% of cases. IV arginine was given for 1-7 days (median, 1 day). A positive clinical response to IV arginine occurred in 47% of stroke-like episodes; an additional 6% of episodes showed clinical benefit from multiple simultaneous treatments that included arginine, confounding sole interpretation of arginine effect. All IV arginine-responsive stroke-like episodes (n=8) received treatment immediately on presentation (p=0.003). Interestingly, the presence of unilateral symptoms strongly predicted arginine response (p=0.01, Chi-Square), where all hemiplegic episodes showed clinical response to IV treatment (n=7); however, all of these cases immediately received IV arginine, confounding interpretation of causality direction. Suggestive trends toward increased IV arginine response were seen in subjects with mtDNA relative to nDNA mutations and in older pediatric subjects, although statistical significance was not reached possibly due to small sample size. No adverse events, including hypotensive episodes, from IV arginine therapy were reported.

Conclusions

Single-center retrospective analysis suggests that IV arginine therapy yields significant therapeutic benefit with little risk in pediatric mitochondrial disease stroke subjects across a wide range of genetic etiologies beyond classical MELAS. Acute hemiplegic stroke in particular was highly responsive to IV arginine treatment. Prospective studies with consistent arginine dosing, and pre- and post-neuroimaging, will further inform the clinical utility of IV arginine therapy for acute metabolic stroke in pediatric mitochondrial disease.

Keywords: Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies, Brain disease, Leigh syndrome, Metabolic stroke, Inborn error, Treatment

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial respiratory chain disease patients are often at risk for developing acute metabolic stroke-like episodes, which are typically rapid-onset events featuring localized, central neurologic system deficits and often lead to persistent disability. Although most closely associated with classical Mitochondrial Encephalopathy with Lactic Acidosis and Stroke-like Episodes (MELAS) syndrome caused by the m.3243A>G heteroplasmic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation [1], stroke-like episodes have been reported in a diverse array of mitochondrial diseases and molecular etiologies, including Leigh syndrome, which has been associated with more than 75 causative genes[2,3], and Kearns Sayre syndrome, which results from mtDNA deletions [4]. Since stroke-like episodes represent an important cause of morbidity and mortality in mitochondrial disorders, gaining deeper understanding of optimal management is critical across the heterogeneous spectrum of mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases [5].

Growing evidence suggests that stroke-like episodes occur in MELAS syndrome due to abnormal nitric oxide flux, perhaps related to abnormal synthesis of the nitric oxide precursors arginine and citrulline [6–8], that may result because citrulline synthesis is an ATP-dependent process [9]. As a result, intravenous arginine has been used as a nitric oxide donor to treat acute stroke-like episodes in MELAS syndrome with reasonably good clinical efficacy [9–11]. Impaired nitric oxide flux also appears to play a pathogenic role in other mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders, beyond MELAS. Although nitric oxide flux has largely been studied in adult-onset mitochondrial disorders, such as chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) [9], low citrulline has been reported as a common finding in Leigh syndrome, particularly when involving mtDNA mutations [12–14]. Indeed, an alternate hypothesis proposed that nitric oxide imbalance in mitochondrial disease may result from proliferation of intracellular reactive oxygen species, which may inactivate and/or react with nitric oxide [15]. This model would suggest that nitric oxide imbalance might occur broadly across metabolic disease, with abnormal nitric oxide flux representing a common pathogenic factor across a diverse group of mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders. Therefore, although the initial acute regressive event in Leigh syndrome is likely attributable to a necrotizing and/or demyelinating process, we hypothesized that subsequent acute, localized stroke-like episodes may result from vasospasm related to impaired nitric oxide flux.

Given the high morbidity and mortality and lack of other demonstrated effective therapies for stroke-like episodes in mitochondrial disease, arginine has gained increasing clinical use since 2005 both as an oral prophylactic agent to mitigate stroke frequency [16,17], as well as an acute intravenous (IV) therapy administered at the time of new-onset stroke-like symptoms[18]. Indeed, a 2014 physician survey of mitochondrial disease physicians suggested 40% of providers utilized arginine [19]. More recently, a 2017 Mitochondrial Medicine Society Practice guidelines Delphi-consensus generated report stated, “IV arginine hydrochloride should be administered urgently in the acute setting of a stroke-like episode associated with the MELAS m.3243 A>G mutation in the MT-TL1 gene and considered in a stroke-like episode associated with other primary mitochondrial cytopathies as other etiologies are being excluded. Patients should be reassessed after 3 days of continuous IV therapy[20].” However, the demonstrated efficacy of IV arginine across diverse molecular etiologies of mitochondrial disease has not previously been systematically studied. Here, we report results of an 8-year single mitochondrial disease center retrospective analysis of IV arginine use at the time of 17 acute stroke-like episodes in 9 pediatric subjects, identified among a larger cohort of 71 pediatric subjects with genetically-confirmed primary mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

Since 2008 we have prospectively enrolled a large cohort of patients with known or suspected mitochondrial disease into Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) internal review board (IRB) approved study #08-6177 (MJF, PI) that allows for medical record reviews and clinical cohort analyses.

Here, we report results of an 8-year retrospective analysis to evaluate IV arginine use at the time of stroke-like episodes in this large cohort, selecting subjects who were under 18 years of age at the time of study enrollment who have molecularly-confirmed, definite, primary mitochondrial disease (n=71). Common MELAS mutation (m.3243A>G) subjects were excluded to focus on use patterns, toxicity, and efficacy of IV arginine in the broader mitochondrial pediatric population. Among this pediatric cohort, 9 subjects received acute arginine IV treatment for one or more stroke-like episodes (n=17 total stroke-like episodes) at CHOP between 2009 and 2016. Retrospectively reviewed data included subject genotype, clinical symptoms, age at time of event, arginine dosing regimen, neuroimaging (when performed), prophylactic therapies, and adverse events.

2.1.1. Inclusion criteria

To be included in this retrospective analysis, subjects needed to have molecular genetic confirmation of a primary mitochondrial respiratory chain disease. Subjects were selected for inclusion in the stroke cohort if they had experienced a rapid-onset of new neurologic symptoms that clinically localized to the central neurologic system, along with clinical suspicion of a stroke-like episode. Stroke-like episodes were included in this analysis if the IV arginine treatment was initiated at CHOP.

2.1.2 Exclusion criteria

Pediatric mitochondrial disease subjects were excluded from analysis if they had no molecular genetic confirmation of their diagnosis (n=3), or if IV arginine treatment was initiated off-site (n=1). Subjects who had one qualifying pediatric stroke-like episode were included in analysis for all subsequent analyses, even if they were greater than 18 years at subsequent episodes.

2.2 IV arginine treatment regimens

Subjects received empiric IV arginine within the course of their clinical care, with dosing based on extrapolation from previously published data in MELAS[10,21,22]. Because no prior prospective study had been performed, variability was evident in dosing regimens used among episodes. Doses ranged from 200 mg/kg/day to 1,500 mg/kg/day. Most subjects received IV arginine as a bolus over 60-90 minutes. However, three episodes were treated with an IV arginine bolus followed by a 24 hour infusion, and a fourth episode involved IV arginine boluses every 8 hours. Two additional episodes were treated with boluses of differing doses on subsequent days. The total length of IV arginine treatment ranged from 1 day to 7 days (median, 1 day.)

2.3 Data collection

Retrospective electronic medical record review was performed to collect molecular diagnosis and clinical phenotype data for each subject. In addition, the following data were collected for each stroke-like episode: subject age, IV arginine dose and administration regimen, timing of arginine therapy, presenting symptoms, whether prophylactic oral arginine or citrulline had been previously used, clinician-assessed clinical treatment response (based on documented assessment by attending Neurologist, Clinical or Biochemical Geneticist) within 24 hours of the end of arginine therapy, and official Radiology reports of any neuroimaging imaging performed during the stroke-like episode.

2.4. Data stratification

An acute stroke-like episode was considered “unilateral” if unilateral weakness involving skeletal muscle or extraocular muscles, or unilateral visual field loss was included in the presenting symptoms, even if accompanied by additional symmetric symptoms. IV arginine treatment was considered “immediate” if it was ordered by the first front-line clinician to whom the subject presented (e.g., emergency room, transport) or “not immediate” if the subject did not receive IV arginine on initial hospital presentation. Because of limited information available in the electronic medical record for this retrospective cohort analysis, the length of time between onset of acute neurologic symptoms and evaluation by a clinician was not consistently known. Therefore, whether IV arginine was provided by the first clinical contact site in the presenting hospital was taking as a proxy to assess the rapidity of treatment and length between historic symptom onset and hospital presentation was not considered in determining treatment immediacy. A subject was considered to have “responded” to arginine if improvement of their symptoms following IV arginine administration was documented in their electronic medical record during the period of their hospital admission within 24 hours of the end of their IV arginine therapy.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was done using Chi-Square analysis for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables (age). A linear mixed-effect model was generated. Statistical analysis was done with the R statistical package (R foundation).

3. Results

3.1 Mitochondrial disease cohort description

9 pediatric subjects were deemed eligible for inclusion in this retrospective analysis, with a combined total of 17 acute stroke-like episodes. Molecular etiology of primary mitochondrial disease in these 9 subjects included mtDNA pathogenic point mutations (MT-ND4, MT-ND5, combined MT-ND4/MT-ND6, MT-TV) in 4 cases, an mtDNA 7.8 kilobase deletion in 1 case, and nuclear gene autosomal recessive disorders in 4 cases (FBXL4, POLG, NDUFS8, SURF1) (Table 1). Stroke-like episodes occurred at ages ranging from 19 months to 23 years (median, 8 years) (Table 1). 3 subjects experienced recurrent stroke-like episodes, accounting for 11 total episodes. Most (70%) subjects were on prophylactic oral arginine (n=5) or citrulline (n=1) at the time of a stroke-like episode. Almost all subjects (90%; n=8) were on a “mitochondrial cocktail” of vitamins at the time of their stroke-like episode; the sole exception was a subject who had been prescribed antioxidant therapy but had been unable to start it due to insurance barriers. Enteral cocktail components differed among subjects. All were on at least one antioxidant: 7/8 were on coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol), with the remaining patient having discontinued ubiquinol to take the investigational EPI-743 and all but one were on an additional antioxidant (Vitamin C, vitamin E or lipoic acid); 7/8 had either riboflavin or a B vitamin complex or both. More variable ingredients included carnitine and/or creatine. (Supplemental Fig. S1). IV arginine was initiated on initial presentation to the hospital in 65% of cases, with enteral arginine or citrulline therapy held during the period of IV arginine treatment). 7 of 17 (41%) acute stroke-like episodes included unilateral symptoms, such as hemiplegia or hemianopsia (Table 1). Most subjects presented immediately to the hospital after the onset of symptoms. However, in 3 cases symptoms had been present for 5-10 days prior to presentation with acute worsening or development of additional symptoms on the day of hospital presentation. In four cases a new stroke-like episode occurred during a hospital admission: 2 cases during treatment of a prior stroke-like episode (after all acute treatment had concluded); a third case during a rehabilitation admission during the prolonged recovery period from a prior stroke-like episode. In a fourth case, an acute stroke-like episode occurred during prolonged hospitalization for multi-organism pneumonia.

Table 1.

Description of subjects and episodes.

| # | Gene | Event | Dose | Prophylactic therapy | Response? | Imaging? | Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ND4/ND6 | Unilateral ophthalmoparesis | 500 mg/kg IV × 1 | 237 mg/kg/day | Yes | Post: T2 hyperintensity in periaqueductal gray matter | 6 |

| 2 | ND5 | Right UE hemiplegia | 500 mg/kg IV × 1 | 150 mg/kg/day | No | ND | 4 |

| 3 | POLG | New partial seizure activity | 500mg/kg IV × 1 | 300 mg/kg/day | no | Post: Baseline | 8 |

| Left hemiplegia, depressed mental status | 500 mg/kg IV × 3 days | 300 mg/kg/day | Yes | Post: T2 hyperintensity in right parasagittal frontal cortex with diffusion restriction. | 8 | ||

| Right hemiplegia, partial seizures on the right | 500 mg/kg × 7 days | 300 mg/kg/day | Unclear due to multiple simultaneous interventions | Head CT Pre: left posterior parietal lobe edema with mild local MRI Post: restricted diffision in the left parietal and occipital lobes, posterior left frontal and right parasaggital parietal lobes and left thalamus |

8 | ||

| 4 | MT-TV | Right hemiplegia, ataxia, poverty of speech, visual floaters, dysmetria. | 250 mg/kg arginine × 1, then 250 mg/kg arginine infusion for 24 hours | Citrulline 10g/m^2/d | Yes, | Post: baseline | 23 |

| Dysarthria and dysphagia, new right hemianopsia | 250 mg/kg × 1; 250mg/kg infusion ×1 | Citrulline 10g/m^2/d | No | ND | 21 | ||

| Head titubation, tremors for about one hour | 250 mg/kg × 1 | Citrulline 10g/m^2/d | Yes | ND | 20 | ||

| Left-sided hemianopsia, left hemiplegia, new partial seizures with deviation of the head to the left | 470 mg/kg ×2 d; 250 mg/kg × 2 d | Citrulline 10g/m^2/d | Partial: improved hemiplegia | Post: T2 hyperintensity in right occipital region and pre- and postcentral gyri | 20 | ||

| Right hemianopsia, right eye deviation, new partial seizures with deviation of the head to the right. | 485 mg/kg × 1 | No | Partial: seizures stopped | Post: Restricted diffusion in medial left occipital lobe | 19 | ||

| Dizziness, left sided weakness, fatigue | 436 mg/kg ×1, 200 mg/kg over 24 hours × 1 | No | Unclear due to multiple simultaneous interventions | Post: Baseline (prior stroke sequelae) | 19 | ||

| 5 | ND4 | Choreiform movements, abnormal speech, ataxia, new clinical seizures, depressed mental status | 500 mg/kg bolus × 3 | No | No | Pre: diffusion restriction in left precentral gyrus Repeat pre: T2 hyperintesity in bilateral cerebral cortices, including frontoparietal, precental, postcentral and parasagittal gyri | 13 |

| 6 | NDUFS8 | Cheyne-Stokes respirations, concerning for stroke in central respiratory center | 500 mg/kg bolus × 1 | 292mg/kg/day | No | ND | 2.9 |

| NDUFS8 | Worsening Cheyne-Stokes respirations | 500 mg/kg/dose bolus q8 ×3 | 292/mg/kg/day | No | ND | 2.9 | |

| 7 | FBXL4 | Left facial, UE and LE hemiplegia | 500 mg/kg/dose bolus × 1 | No | Partial: Strength normalized; persistent left hyporeflexia | Post: T2 hyperintensity right parietal periventricular white matter & thalamus | 1.7 |

| 8 | mtDNA deletion | Ataxia, dysmetria, worsened ophthalmoplegia, atonic episodes | Arginine 500 mg/kg/dose bolus × 5 days | No | Atonia resolved | Post: baseline (Leigh syndrome) | 12 |

| 9 | SURF 1 | Cheyne-Stokes | 500 mg/kg × 1 | 130 mg/kg/day | No | ND | 3 |

ND = Not Done. SLE = stroke-like episode. UE = upper extremity.

3.2. IV arginine response

In no case was immediate pre- and post-treatment neuroimaging studies available. For 11 stroke-like episodes, brain MRI was performed either before or after treatment. In 7 of these 11 episodes, MRI correlate of clinical stroke was seen, primarily involving the occipital lobe (5 cases) and occasionally with more extensive cortical involvement (Figure 3). In all cases without an imaging correlate, imaging was obtained after arginine had been given and the patient had clinically returned completely or almost completely to baseline. Owing to the absence of paired imaging, therapeutic response to IV arginine was assessed clinically. Overall, 47% of acute stroke-like episodes showed a positive clinical response to IV arginine, with another 6% of episodes showing clinical improvement that could not be directly attributed solely to IV arginine response due to concurrent use of other therapies (e.g., antiepileptic treatment). Of the 8 clearly responsive cases, 6/8 (75%) had some clinical response documented within 12 hours of having received the first dose of IV arginine. One of these 8 patients had continued improvement for another 48 hours of daily arginine boluses, and an additional case (1 of 8, 12.5%) who did not initially respond showed clinical response within 48 hours of daily IV arginine boluses. No subject displayed clear continued clinical improvement beyond 48 hours of treatment. 50% of subjects had residual persistent neurologic symptoms, while 50% responded completely back to baseline by hospital discharge. Two subjects required prolonged inpatient rehabilitation after stroke-like episodes (subject 3, IV arginine treated stroke-like episode 1; subject 4, IV arginine treated stroke-like episode 3.)

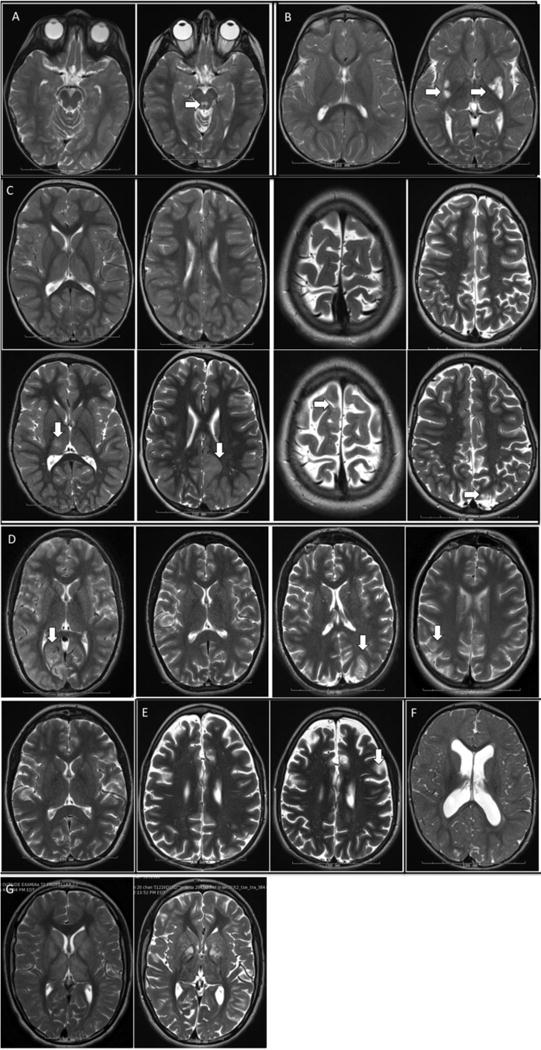

Figure 3. Brain neuroimaging studies in subjects who received IV arginine for acute clinical stroke-like episodes.

T2-weighted Brain MRIs available before and after acute stroke-like episodes (SLE) for each study subject (diffusion-weighted images are not shown, but are described). A. Subject 1, brain MRI 2 years prior (left) and 4 weeks after (right) SLE & IV arginine treatment showed new T2 prolongation in periaqueductal gray, not accompanied by diffusion restriction. B. Subject 2, brain MRI 6 months prior (left) and 7 months after (right) SLE & IV arginine treatment showed new T2 prolongation in left greater than right posterior putamen, which was also associated with new T2 prolongation in the superior colliculi and left caudate (not shown); there was accompanying diffusion restriction. C. Subject 3, brain MRI 13 months prior to SLE (top first panel); immediately after first SLE (bottom first panel) shows new T2 prolongation in the thalamus with a mixed diffusion pattern (SLE was not treated and not described in the table as it occurred prior to diagnosis); 2 years and 1 month prior to 2nd SLE (top 2nd panel) and 1 day after second SLE; on day 2/7 of IV arginine, (bottom 2nd panel) MRI showed new T2 prolongation in the cortical and subcortical areas in the left parietal and occipital regions more than the left frontal, right parasaggital parietal and left thalamus, all with diffusion restriction (not shown); 3 months prior to (top 3rd panel) and 1 day after third SLE, on day 2/3 of IV arginine (bottom 3rd panel) MRI showed new T2 prolongation in the right parasagittal frontal with diffusion restriction; 1 week before (top 4th panel) and 1 day after fourth SLE & IV arginine treatment (bottom 4th panel) showed new T2 prolongation in the left medial occipital gyrus with subtle diffusion restriction. D. Subject 4, brain MRI at first SLE (first panel) showed T2 hyperintensity in the medial right occipital lobe, with extension into the posterior temporal lobe, associated with restricted diffusion (this SLE was not treated and not described in the table as it occurred prior to diagnosis.); brain MRI 1 day after 2nd SLE during day 1/1 of IV arginine infusion (2nd panel) showed no new changes; brain MRI 1 day after 3rd SLE & IV arginine treatment (3rd panel) shows T2 hyperintensity in medial left occipital lobe associated with diffusion restriction, with increased perfusion through remainder of left occipital lobe; brain MRI during 4th SLE, prior to IV arginine treatment (4th panel) showed subtle T2 hyperintensity in the medial right parieto-occipital and occipital region, with diffusion restriction, as well as punctate areas of T2 hyperintensity with diffusion restriction in the bilateral pre- and postcentral gyri; brain MRI immediately after 7th SLE, after arginine treatment 1/1 (5th panel) showed no new changes. Subject 5, brain MRI 2 years prior (left) and 13 days after SLE (right), 1 day prior to IV arginine treatment showed new T2 hyperintensity in the cortex, predominately in the frontoparietal region, with diffusion restriction (changes were present, but very subtle immediately after SLE; images not shown.) F. Subject 7, brain MRI 1 day after SLE & IV arginine treatment showed no specific signal abnormalities; incidental note of abnormal cortical morphology. G. Subject 8, brain MRI 2 months prior to (left) and 3 days after SLE & IV arginine treatment showed no interval change; the substantial apparent difference in T2 signal abnormality throughout the bilateral basal ganglia (and periventricular region, not shown) was attributed technical differences; the baseline MRI was performed in a different institution.

Of the 3 subjects who had recurrent stroke-like episodes, 2 (subjects #3 and #4) had experienced both IV arginine responsive and non-responsive episodes over a period of several years. The episodes occurred at multiple distinct locations in the brain (primarily in the cortex) in both subjects. Neither of these subjects had neuroimaging performed at the time of their non-responsive episodes. Notably, both of these subjects also had experienced an untreated stroke-like episode prior to their definitive mitochondrial disease diagnosis that left them with significant residual deficits. The third subject who experienced recurrent episodes (subject #6) had two episodes within several days of each other, both localizing to the brainstem; neuroimaging was not performed. She did not respond to IV arginine treatment for either episode.

Two subjects with non-responsive acute stroke-like episodes, both of whom presented with Cheyne-Stokes respirations, ultimately died related to their stroke-like episodes. Subject #6, a 2-year-old girl with NDUFS8-related complex I disease received IV arginine treatment at least one day after an insidious onset of symptoms, which occurred during a prolonged hospital admission for treatment-refractory pneumonia with acute respiratory failure, and did not show neurologic response to IV arginine treatment. Three days later, she had acute decompensation of her central respiratory drive, and received a second round of IV arginine treatment the following day without noted clinical improvement. The decision was made not to intubate and the subject passed due to respiratory failure. Subject #9, a 3-year-old girl with SURF1-related complex IV disease received IV arginine treatment 1 day after presenting with an abnormal respiratory pattern. However, she did not show clinical response and the decision was made not to intubate but continue non-invasive ventilation after which she passed due to acute respiratory failure.

No adverse events including hypotension, hypoglycemia or acidosis were reported in any subject from IV arginine therapy. However, in one case (subject #5), IV arginine was delayed for 14 days from the time of presentation because of concern that arginine would exacerbate his co-morbid hypotension. After 13 days of symptoms, a repeat MRI showed worsening of his brain signal abnormalities and continued diffusion restriction, consistent with a metabolic stroke (Figure 3), based on which the decision was made to initiate IV arginine the next day. He did not show clinical response to the delayed IV arginine therapy.

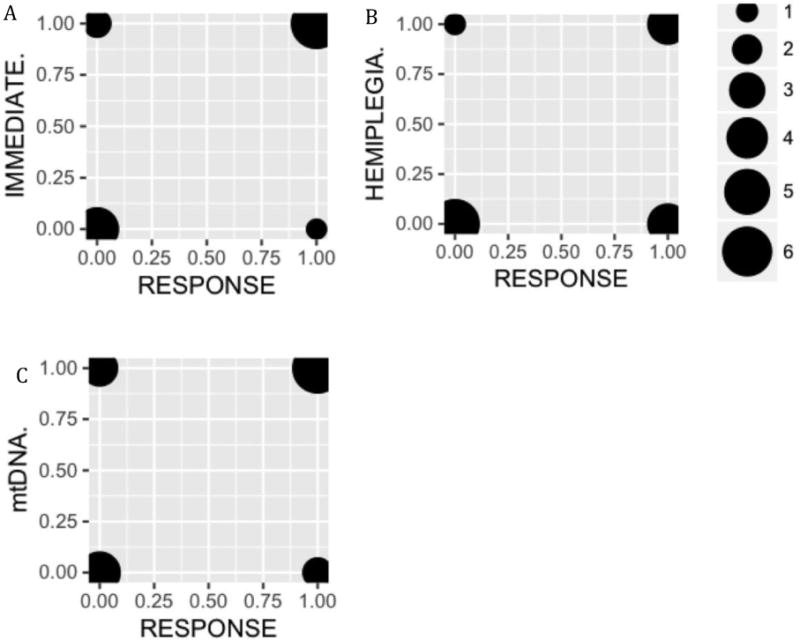

3.3 Predicting IV arginine responders

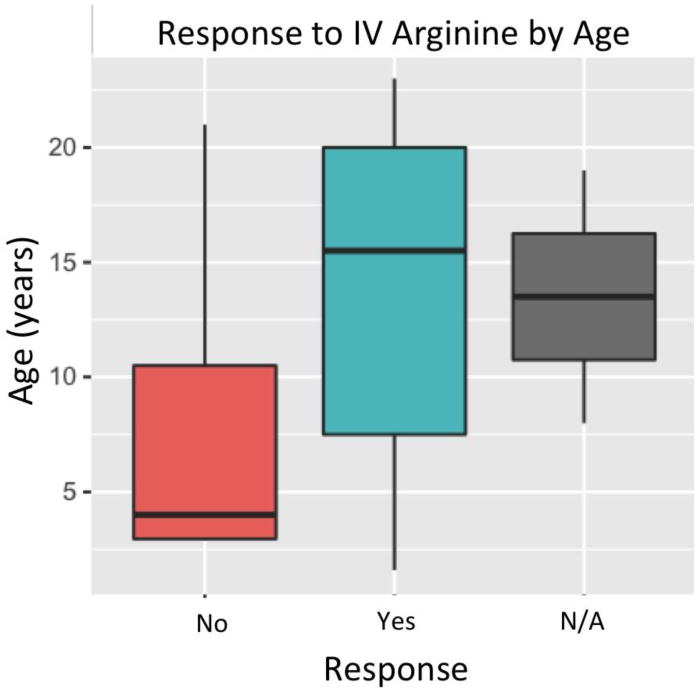

We hypothesized that therapeutic response to IV arginine could be predicted based on subject age, presenting symptoms of the episode (hemiplegic versus non-hemiplegic), treatment timing (immediate versus non-immediate), and molecular etiology (mtDNA versus nuclear). Therefore, we attempted to generate a mixed effect-linear model to account for these key variables. Unfortunately, a statistically significant model could not be generated, likely due to the small sample size of individuals with acute stroke-like episodes who received IV arginine. However, using chi-square analysis and Mann-Whitney U testing to analyze the independent role of each variable revealed that all of the acute stroke-like episodes that clinically responded to IV treatment (n=8 of 17 (47%) total episodes) received treatment immediately on hospital presentation (p=0.003; Figure 2). The presence of unilateral symptoms also strongly predicted IV arginine response (p=0.002 by Chi-Square; Figure 2), with all hemiplegic episodes showing clinical response to IV treatment (n=7). However, all of these cases also received arginine immediately, making it difficult to determine the causal factor. In addition, two trends were apparent that did not reach statistical significance, likely due to small cohort sample size. These included a trend towards increased IV arginine responsiveness in patients with mtDNA relative to nDNA gene disorders (Figure 2), and a trend toward increased IV arginine responsiveness in older pediatric subjects (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Response to IV arginine therapy by key factor analysis.

IV arginine treatment responders and non-responders are shown on the right and left side of each graph, respectively. Bubble sizes correspond to subject number per group. A. Subjects are grouped by clinical response and whether IV arginine treatment was given immediately on hospital presentation (top) or not (bottom) (p= 0.003, Chi-Square). B. Subjects are grouped by clinical response and the presence (top) or absence (bottom) of hemiplegia as a presenting symptom (p=0.002, Chi-Square). C. Subjects are grouped by clinical response and molecular lesion: nuclear DNA (bottom) or mtDNA (top) (p=0.10, Chi-Square).

Figure 1. Response to IV arginine therapy at time of acute stroke-like symptoms by age.

N/A = not clearly assessable due to multiple simultaneous treatment interventions at time of acute stroke-like symptoms. (p=0.24 by Mann-Whitney U Test.)

4. Conclusions

Here, we report our 8-year, single mitochondrial disease center experience of treating acute stroke-like episodes with IV arginine in diverse pediatric mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases beyond classical MELAS syndrome. Collectively, we report effects of IV arginine empiric treatment during 17 stroke-like episodes in 9 pediatric patients who had a variety of primary mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases that included mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome, Kearns-Sayre syndrome, Leigh syndrome, and atypical MELAS presentations. These data represent one of the largest clinical case series reporting acute stroke-like episodes in diverse pediatric mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases, emphasizing the contribution of stroke-like episodes to morbidity in many pediatric mitochondrial diseases. Indeed, acute stroke-like episodes were fatal in 6% of our cohort, and left subjects with residual neurologic deficits in 35% of episodes. Partly due to recurrent episodes in 3 subjects, every one of the 9 subjects in the acute stroke cohort was ultimately left with a residual deficit from a stroke-like episode, although the degree of neurologic deficit was subtle in some cases. Consistent with the hypothesis that nitric oxide flux impairment causes dysfunction in many mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases [9], 47% of subjects clinically responded to empiric IV arginine therapy in the acute hospital setting. Although some responses were only partial, notably, two of the three subjects who developed recurrent stroke-like episodes had significant baseline disability from untreated episodes prior to diagnosis. These two subjects had additional (subject #3: 3, subject #4: 6) subsequent stroke-like episodes treated with IV arginine, all of which resulted in much milder residual neurologic impairment than the untreated episodes. This suggests that even partial amelioration of neurologic impairment with IV arginine may yield clinical benefit. Overall, these data suggest that IV arginine has broad utility in treating stroke-like episodes in a broad array of mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases. While prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study would be necessary to definitively delineate the effect of self-resolution to IV arginine treatment effects, such a trial design may well be difficult to enroll given the limited array of clinical treatment options for this patient population and the low apparent risk of IV arginine therapy at the time of acute metabolic stroke.

Several novel insights into IV arginine therapeutic efficacy in acute stroke-like episodes in pediatric mitochondrial disease were gained from this retrospective analysis. Specifically, we found that mitochondrial disease subjects are significantly more responsive to IV arginine if they receive therapy immediately upon presentation with a new neurologic deficit. In addition, subjects presenting with hemiplegia or hemianopsia appear to be highly responsive to IV arginine treatment, although the complete overlap in our study between those subjects with unilateral symptoms with those who were treated immediately makes it impossible to distinguish whether either is a single predictive factor. Nonetheless, IV arginine was not associated with any adverse effects in this study. Therefore, our findings suggest that there should be a very low barrier to an empiric clinical trial of IV arginine therapy in a patient with known mitochondrial respiratory chain disease at the time of acute stroke-like presentation.

This study was exploratory and retrospective in nature, analyzing response to IV arginine therapy that was empirically used in the course of acute clinical care. Multiple limitations stem from the small sample size and retrospective nature of this analysis. One major limitation is the variability in IV arginine dosing regimens administered, although as the period analyzed progressed, nearly all episodes were treated with a standardized regimen of 500 mg/kg IV arginine bolus at presentation and then repeated every 24 hours as indicated based on the presence of ongoing symptoms. The small sample size further limits full statistical modeling. Because of the retrospective analysis, clinical neuroimaging was limited, making it difficult to define the exact neuropathology of each event. Ideally, access to routine pre- and post-arginine brain imaging would have been preferred to gain deeper insight into the specific brain regions most amenable to IV arginine therapy. However, it is recognized that this may not be clinically necessary given the lack of other therapeutic options, the risk of anesthesia required to intubate Leigh syndrome pediatric patients to obtain high-quality neuroimaging data, and the overall favorable safety-risk profile of administering IV arginine in the acute clinical setting. The retrospective analysis further limited analysis of the exact timing interval between acute neurologic symptom onset to treatment initiation with IV arginine or amelioration of symptoms, making it difficult to determine precise guidelines for IV arginine management based on these data. Finally, since so little information is known about the natural history of stroke-like episodes in this patient population, it is possible that symptoms would have spontaneously remitted without therapy. However, the high historic mortality of pediatric Leigh syndrome is estimated at 35% in childhood, which is significantly higher than in the current reported cohort, as we postulate that untreated acute neurologic strokes likely contributed to this higher historic mortality [23,24]. Nonetheless, we feel that this exploratory retrospective cohort study of a serious clinical event having high morbidity in the pediatric LS population offers several useful insights to enable improved metabolic disease community standardization of care for the management acute stroke-like episodes in diverse pediatric mitochondrial diseases. Most importantly, we conclude based on these data that IV arginine use in molecularly-confirmed definite mitochondrial disease patients at the time of acute stroke-like episodes will be generally well-tolerated, may improve clinical recovery and neurodevelopmental outcomes, and provide a foundation for more in-depth treatment response analyses.

Overall, this work reports the largest clinical retrospective analysis to gain deeper insights into the efficacy and toxicity of IV arginine for clinically suspected acute stroke-like episodes in patients with molecularly-confirmed primary mitochondrial respiratory chain diseases beyond MELAS. As clinical use of arginine expands to include these patients[20], it is critical to evaluate the data for its use. This work suggest that IV arginine may be of benefit in improving the clinical outcome of acute neurologic decompensation in patients with stroke-like episodes, especially if given quickly, in patients presenting with unilateral symptoms such as hemiplegia or hemianopsia, and perhaps in the teenage population and among those with mtDNA disorders. While acute stroke-like episodes carry serious threats of morbidity and mortality in primary mitochondrial disease subjects, arginine is a relatively benign and well-tolerated treatment with strong scientific rationale for clinical use in this patient population. Therefore, while further studies are necessary and desirable to fully understand its full impact, results of this retrospective study analysis support strong consideration for IV arginine clinical use at the time of acute stroke-like episode onset in the pediatric mitochondrial disease population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and families who participated in this study; the clinicians of the CHOP mitochondrial medicine center, including Dr. Zarazuela Zolkipli-Cunningham and Dr. Xilma Ortiz-Gonzalez; the research study coordinator, Elizabeth McCormick, CGC; and our colleagues at CHOP who took care of these patients, especially the metabolism and neurology teams.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH T32-GM008638-20 (R.D.G.) and the Holveck Research Fund (M.J.F.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kurlyama M, Igata A. Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike syndrome (MELAS) Ann Neurol. 1985;18:625–625. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lake NJ, Compton AG, Rahman S, Thorburn DR. Leigh syndrome: One disorder, more than 75 monogenic causes. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:190–203. doi: 10.1002/ana.24551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morin C, Dubé J, Robinson BH, Lacroix J, Michaud J, De Braekeleer M, Geoffroy G, Lortie A, Blanchette C, Lambert MA, Mitchell GA. Stroke-like episodes in autosomal recessive cytochrome oxidase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:389–92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10072055 (accessed May 28, 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furuya H, Sugimura T, Yamada T, Hayashi K, Kobayashi T. A case of incomplete Kearns-Sayre syndrome with a stroke like episode. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1997;37:680–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9404143 (accessed May 28, 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finsterer J, Stollberger C. Stroke in myopathies. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:6–13. doi: 10.1159/000255968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Hattab AW, Emrick LT, Hsu JW, Chanprasert S, Almannai M, Craigen WJ, Jahoor F, Scaglia F. Impaired nitric oxide production in children with MELAS syndrome and the effect of arginine and citrulline supplementation. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;117:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Hattab AW, Jahoor F. Assessment of Nitric Oxide Production in Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-Like Episodes Syndrome with the Use of a Stable Isotope Tracer Infusion Technique. J Nutr. 2017:jn248435. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.248435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naini A, Kaufmann P, Shanske S, Engelstad K, De Vivo DC, Schon EA. Hypocitrullinemia in patients with MELAS: an insight into the “MELAS paradox”. J Neurol Sci. 2005;229–230:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Hattab AW, Emrick LT, Craigen WJ, Scaglia F. Citrulline and arginine utility in treating nitric oxide deficiency in mitochondrial disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubota M, Sakakihara Y, Mori M, Yamagata T, Momoi-Yoshida M. Beneficial effect of l-arginine for stroke-like episode in MELAS. Brain Dev. 2004;26:481–483. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenig MK, Emrick L, Karaa A, Korson M, Scaglia F, Parikh S, Goldstein A. Recommendations for the Management of Strokelike Episodes in Patients With Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Strokelike Episodes. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:591. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.5072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debray FG, Lambert M, Allard P, Mitchell GA. Low Citrulline in Leigh Disease: Still a Biomarker of Maternally Inherited Leigh Syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2010;25:1000–1002. doi: 10.1177/0883073809351983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori M, Mytinger JR, Martin LC, Bartholomew D, Hickey S. m.8993T>G-Associated Leigh Syndrome with Hypocitrullinemia on Newborn Screening. JIMD Rep. 2014:47–51. doi: 10.1007/8904_2014_332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balasubramaniam S, Lewis B, Mock DM, Said HM, Tarailo-Graovac M, Mattman A, van Karnebeek CD, Thorburn DR, Rodenburg RJ, Christodoulou J. Leigh-Like Syndrome Due to Homoplasmic m.8993T>G Variant with Hypocitrullinemia and Unusual Biochemical Features Suggestive of Multiple Carboxylase Deficiency (MCD) JIMD Rep. 2016:99–107. doi: 10.1007/8904_2016_559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coman D, Yaplito-Lee J, Boneh A. New indications and controversies in arginine therapy. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koga Y, Akita Y, Junko N, Yatsuga S, Povalko N, Fukiyama R, Ishii M, Matsuishi T. Endothelial dysfunction in MELAS improved by l-arginine supplementation. Neurology. 2006;66:1766–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000220197.36849.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lekoubou A, Kouamé-Assouan AE, Cho TH, Luauté J, Nighoghossian N, Derex L. Effect of long-term oral treatment with L-arginine and idebenone on the prevention of stroke-like episodes in an adult MELAS patient. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2011;167:852–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, Yatsuga S, Povalko N, Tanabe Y, Fujimoto S, Matsuishi T. L-arginine improves the symptoms of strokelike episodes in MELAS. Neurology. 2005;64:710–2. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151976.60624.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh S, Goldstein A, Koenig MK, Scaglia F, Enns GM, Saneto R. Practice patterns of mitochondrial disease physicians in North America. Part 2: treatment, care and management. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:681–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh S. Patient Care Standards for Primary Mitochondrial Disease: A Consensus Statement from the Mitochondrial Medicine Society. Genet Med. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.107. (n.d.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh S, Saneto R, Falk MJ, Anselm I, Cohen BH, Haas R, T.M. Medicine Society A modern approach to the treatment of mitochondrial disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2009;11:414–30. doi: 10.1007/s11940-009-0046-0. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19891905 (accessed December 11, 2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Hattab AW, Adesina AM, Jones J, Scaglia F. MELAS syndrome: Clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Mol Genet Metab. 116:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.06.004. (n.d.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scaglia F, Towbin JA, Craigen WJ, Belmont JW, Smith EO, Neish SR, Ware SM, Hunter JV, Fernbach SD, Vladutiu GD, Wong LJC, Vogel H. Clinical spectrum, morbidity, and mortality in 113 pediatric patients with mitochondrial disease. Pediatrics. 2004;114:925–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verity CM, Winstone AM, Stellitano L, Krishnakumar D, Will R, McFarland R. The clinical presentation of mitochondrial diseases in children with progressive intellectual and neurological deterioration: a national, prospective, population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:434–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]