Abstract

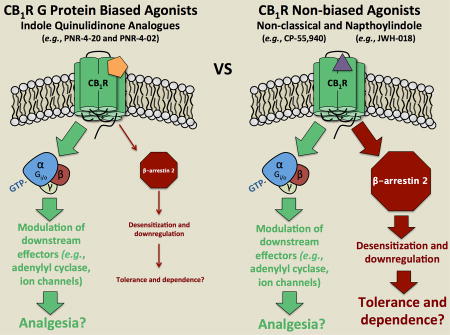

The human cannabinoid subtype 1 receptor (hCB1R) is highly expressed in the CNS and serves as a therapeutic target for endogenous ligands as well as plant-derived and synthetic cannabinoids. Unfortunately, acute use of hCB1R agonists produces unwanted psychotropic effects and chronic administration results in development of tolerance and dependence, limiting the potential clinical use of these ligands. Studies in β-arrestin knockout mice suggest that interaction of certain GPCRs, including μ-, δ-, κ-opioid and hCB1Rs, with β-arrestins might be responsible for several adverse effects produced by agonists acting at these receptors. Indeed, agonists that bias opioid receptor activation toward G-protein, relative to β-arrestin signaling, produce less severe adverse effects. These observations indicate that therapeutic utility of agonists acting at hCB1Rs might be improved by development of G-protein biased hCB1R agonists. Our laboratory recently reported a novel class of indole quinulidinone (IQD) compounds that bind cannabinoid receptors with relatively high affinity and act with varying efficacy. The purpose of this study was to determine whether agonists in this novel cannabinoid class exhibit ligand bias at hCB1 receptors. Our studies found that a novel IQD-derived hCB1 receptor agonist PNR-4-20 elicits robust G protein-dependent signaling, with transduction ratios similar to the non-biased hCB1R agonist CP-55,940. In marked contrast to CP-55,940, PNR-4-20 produces little to no β-arrestin 2 recruitment. Quantitative calculation of bias factors indicates that PNR-4-20 exhibits from 5.4-fold to 29.5-fold bias for G protein, relative to β-arrestin 2 signaling (when compared to G protein activation or inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation, respectively). Importantly, as expected due to reduced β-arrestin 2 recruitment, chronic exposure of cells to PNR-4-20 results in significantly less desensitization and down-regulation of hCB1Rs compared to similar treatment with CP-55,940. PNR-4-20 (i.p.) is active in the cannabinoid tetrad in mice and chronic treatment results in development of less persistent tolerance and no significant withdrawal signs when compared to animals repeatedly exposed to the non-biased full agoinst JWH-018 or Δ9-THC. Finally, studies of a structurally similar analog PNR-4-02 show that it is also a G protein biased hCB1R agonist. It is predicted that cannabinoid agonists that bias hCB1R activation toward G protein, relative to β-arrestin 2 signaling, will produce fewer and less severe adverse effects both acutely and chronically.

Keywords: Biased agonist, G protein-dependent signaling, G protein-independent signaling, Indole quinuclidine, Human cannabinoid type-1 receptor, β-arrestin 2 recruitment, Seven transmembrane receptors

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1.0 Introduction

Cannabinoid receptors are seven transmembrane receptors (7TMRs) that couple to G proteins and are characterized into two subtypes, cannabinoid type 1 (CB1R) and type 2 (CB2R) receptors (1, 2). CB1Rs are ubiquitously expressed in the central nervous system and bind the endogenous cannabinoids 2-archadinoylglycerol and anandamide, which mediate retrograde signaling elicited by endocannabinoids at GABAergic and glutamatergic presynaptic neurons (3, 4). CB2Rs are found peripherally on circulating immune cells (5, 6). Like most 7TMRs, CB1 and CB2Rs are capable of adopting a number of distinct conformations that transduce G protein-dependent and -independent signaling (7, 8). G protein-dependent signaling occurs upon agonist binding to CBRs, followed by interaction with pertussis toxin sensitive Gi/o proteins and regulation of a number of downstream intracellular effectors including adenylyl cyclase, inward rectifying K+ channels and voltage gated Ca++ channels (9–11). Alternatively, CBR agonists also modulate G protein-independent signaling responsible for recruitment of the proximally located, intracellular scaffolding proteins β-arrestin 1 and 2 (12, 13). While similar in homology (14), β-arrestin 1 and 2 exhibit distinct functional properties. β-arrestin 1 is primarily responsible for mediating MAP kinase signaling that includes regulation of p38 and ERK1/2 activity, while β-arrestin 2 participates in agonist-induced desensitization and down-regulation of CBRs (13).

In recent years, many groups have developed novel compounds termed “biased ligands” that act selectively at respective 7TMRs (15–18). These biased ligands are pharmacologically unique because they stabilize subsets of receptor conformations that invoke distinct G protein-dependent or –independent signaling (19). Currently, development of novel analgesics acting via CB1, μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors is focused on identification of G protein-selective compounds that are devoid of β-arrestin 2 recruitment (7, 16, 20, 21). Evidence suggests that analgesic compounds exhibiting bias for G protein signaling may exhibit reduced adverse effects when administered both acutely and/or chronically (21). For example, β-arrestin 2-knockout mice acutely administered the CB1R partial agonist, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), display enhanced antinociception and hypothermia (12). Furthermore, chronic treatment of β-arrestin 2-knockout mice with Δ9-THC produces reduced levels of CB1R desensitization and down-regulation, as well as attenuated antinociceptive tolerance (12, 21). Observations that both acute (e.g., antinociception) and chronic (e.g., development of tolerance) responses to Δ9-THC are markedly improved in β-arrestin 2-knockout mice indicate that future development of cannabinoid agonists that bias CB1R signaling toward G protein, and away from β-arrestin 2 pathways, might exhibit significantly reduced adverse effects.

Several novel analgesics that act as G protein biased agonists via μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors have been identified (15, 22, 23), and some of these compounds have advanced to clinical trials (24). Unfortunately, discovery of cannabinoid ligands that bias CB1R signaling has been minimal (21). Although a number of structurally diverse classes of cannabinoid ligands have been developed (25–27), CB1R agonists characterized to date exhibit relatively equivalent coupling to both G-protein and β-arrestin 2 pathways (28). Our group recently characterized a novel class of indole quinulidinone (IQD) analogues that exhibit high nanomolar affinity for CB1Rs (29), and act as partial to full CB1R agonists for modulation of the Gi/Go-coupled intracellular effector adenylyl cyclase (30). Although IQD analogues have been shown to clearly couple CB1Rs to G protein-dependent pathways, the ability of compounds in this class to produce CB1R-mediated G protein-independent recruitment of β-arrestin 2 has yet to be determined.

Analogues based on the novel IQD structural scaffold (30) might bias coupling of CB1Rs towards either G protein or β-arrestin 2 signaling pathways. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether cannabinoid agonists in this class exhibit ligand bias at CB1Rs. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing human CB1Rs (hCB1R) were used to examine the ability of IQD analogues to modulate hCB1R coupling to G protein-dependent and –independent signaling pathways, and adult male NIH-Swiss mice were used to assess in vivo pharmacological effects using the cannabinoid tetrad assay.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Materials

IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 were synthesized as previously described (30) and were dissolved in 100% DMSO to 10 mM stock concentrations for in vitro assays. WIN-55,212-2, JWH-018, CP-55,940, and DAMGO were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom). GTPγS was purchased from EMD Chemical (Gibbstown, NJ). [3H]CP-55,940 (52.6 Ci/mmol) was acquired from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA) and [35S]GTPγS (1250 Ci/mmol) was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). PathHunter™ enzyme fragment complementation (EFC) experimental reagent was purchased from DiscoverRx Corporation (Fremont, CA). All other reagents used were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

2.2. Animals

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences institutional animal care and use committee (e.g., IACUC) approved the animal use protocol employed in this study. All efforts were taken to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. Adult male NIH-Swiss mice (9 week old) were purchased from Harlan laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, Indiana). All animals were housed three per cage (15.24 × 25.40 × 12.70 cm3) in a temperature-controlled room in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility. Room conditions were maintained at 22 ± 2 °C and 45–50% humidity, with lights set to a 12-h light/dark cycle. Animals were fed Lab Diet rodent chow (Laboratory Rodent Diet no. 5001, PMI Feeds, St Louis, MO) ad libitum until immediately before testing. All test conditions used groups of either five or six mice which were randomly assigned to experimental groups, and all mice were drug-naïve before testing.

2.3 Cell Culture assays

CHO-K1 cells stably expressing wild-type recombinant human CB1 receptors (CNR1) were purchased from DiscoverRx Corporation (Fremont, CA) and designated CHO-hCB1-Rx. CHO-K1 cells stably co-expressing human CB1 receptors and β-arrestin 2 (ARRB2), each tagged with complementiary ProLink® β-galactisidase enzyme fragments, were also obtained from DiscoverRx Corporation and designated as CHO-β2-hCB1. CHO-K1 cells were stably transfected with the human μ-opiod receptor (MOR, CHO-hMOR) in our laboratory as previously reported (31). CHO-β2-hCB1 and CHO-hCB1-Rx cells were cultured in HAM’s F-12 K media (ATCC, Manssas, VA) while the CHO-hMOR cell line was cultured in DMEM (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA). Media for CHO-β2-hCB1 cells contained 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Sacramento, CA), 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 500 µg/ml of geneticin (or G418; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 250 µg/ml hygromycin B (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), while media for CHO-hCB1-Rx and CHO-hMOR cell lines contained 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Sacramento, CA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 250 µg/mL of G418 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All cell types were cultured in a humidified chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2, harvested when flasks were approximately 70% confluent, and only cells from passages 4–15 were used in all experiments.

2.4 Membrane Preparation

Membranes were prepared as described previously (30). Briefly, cell pellets from CHO-β2-hCB1, CHO-hCB1-Rx and CHO-hMOR cells were homogenized separately with 10 complete strokes utilizing a 40 mL Dounce glass homogenizer in ice-cold buffer containing 3 mM MgCl2, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, and 1 mM EDTA. Homogenized samples were then centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were decanted and pellets were re-suspended in ice-cold buffer, homogenized again, and centrifuged similarly two additional times. After the last centrifugation step, supernatants were decanted and remaining cell membranes were re-suspended in ice-cold 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 to achieve an approximate protein concentration of 5 mg/ml. Membrane homogenates were divided into respective aliquots and stored at −80°C for future use. A 100 µl aliquot of each membrane preparation was removed prior to freezing and the protein concentration was determined using BCA™ Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

2.5 Competition Receptor Binding

Competition receptor binding was conducted as previously described (32). In brief, respective reaction mixtures contained increasing concentrations of the non-radioactive competing ligands in a 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.2 nM [3H]-CP55,940, 5 mM MgCl2, and either 50 µg of CHO-β2-hCB1 or 100 µg of CHO-hCB1-Rx membrane homogenates. The total volume of the incubation mixture was 1 ml. All reactions were mixed and allowed to reach equilibrium binding via incubation at 37°C for 15 min. Non-specific binding was defined as the amount of radioligand binding remaining in the presence of a 1 µM concentration of the non-radioactive, high affinity, non-selective CBR agonist WIN-55,212-2. Binding was terminated via rapid vacuum filtration through glass fiber filters (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD), followed by four 5 ml washes of ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Four ml of Scintiverse© scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added to respective filters and radioactivity was quantified 24 hr later utilizing a Packard-Tri-carb 2100/TR liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT).

2.6 [35S]GTPγS Binding

The GTPγS binding assay was used to measure G-protein activation, as previously described (33). Briefly, 25 µg of CHO-hCB1-Rx or 50 µg of CHO-hCB1-Rx and CHO-hMOR membrane homogenates were added to reaction mixtures containing 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS, 10 µM GDP, 0.1% bovine serum albumin and the specified concentrations of ligand to be examined. The total volume of the incubation mixture was 1 ml. After mixing each solution, reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Nonspecific binding was defined by the amount of radioactivity remaining in the presence of 1 µM non-radiolabeled GTPγS. Reactions were terminated by rapid vacuum filtration through glass fiber filters followed by four washes with 5 ml of ice cold 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Four ml of Scintiverse© scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added to the filters and the amount of radioactivity was quantified 24 hr later utilizing a Packard-Tri-carb 2100/TR liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT).

2.7 Measurement of Forskolin-Stimulated Intracellular cAMP Levels in Intact Cells

CHO-β2-hCB1 or CHO-hMOR cells were plated separately into 24-well plates at a density of 7 × 106 cells/plate and incubated overnight in the respective culture media previously described at 37°C in 5% CO2. The next day, culture media was gently removed from each well and replaced with 500 µl pre-incubation mixture containing either HAM’s F-12 K (CHO-β2-hCB1) or DMEM (CHO-hMOR) with 2 μCi/well [3H]adenine, 0.9% NaCl, and 500 µM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxathine (IBMX), as previously reported (30). Cells were subsequently incubated for 3 hr at 37°C. The pre-incubation mixture was removed and specified concentrations of each respective ligand were added to the individual wells for 15 min at 30°C in a Krebs-Ringer-HEPES solution (110mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 55mM sucrose, 25mM glucose, 5mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) containing 10 µM forskolin and IBMX. Reactions were terminated by adding 50 µl 2.2N HCl and [3H]cAMP was extracted utilizing alumina column chromatography. Radioactivity contained in 4 ml of the final column eluate was counted by a Packard-Tri-carb 2100/TR liquid scintillation counter after adding 10 ml of liquid scintillation cocktail.

2.8 β-arrestin 2 Recruitment Assay

β-arrestin 2 recruitment assays were conducted utilizing CHO-β2-hCB1 cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol (DiscoveRx Corporation, Fremont, CA) with minor modifications. Specifically, CHO-β2-hCB1 cells were seeded into 384-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/well in 10 µl of supplied Cell Plating Reagent 0 (DiscoveRx) and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Initial optimization experiments determined that the relatively small incubation volume (10 µl) does not significantly decrease due to evaporation after overnight incubation. Lack of media evaporation is likely due to culture of cells in a humidified incubator. The next day, vehicle and drug dilutions, each containing 5% DMSO, were prepared in Cell Plating Reagent 0 at the indicated concentrations. Two and one-half µl of respective drugs were added to quadruplicate wells of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells and incubated for 90 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. A final 1% DMSO concentration was achieved upon drug addition to CHO-β2-hCB1 cell wells. Following incubation, detection reagent (DiscoveRx) was prepared by combining 19 parts of Cell Assay Buffer, 5 parts Substrate Reagent 1, and 1 part Substrate Reagent 2. Six µl of prepared detection reagent was then added to each well containing vehicle or drug-treated CHO-β2-hCB1 cells and was allowed to incubate at room temperature for 1 h. Following incubation, luminescence was determined by a SpectraMax® Plus plate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.9 CB1 Receptor Desensitization and Down-Regulation Following Chronic Treatment

CHO-β2-hCB1 and CHO-hCB1-Rx cells were plated in culture media into 6-well plates at a density of 7×106 cells/plate and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. The next day, media was removed and each well was washed three times with 6 ml of serum free HAM’s F-12 K media. Following the last wash, 6 ml of serum free HAM’s F-12 K media, and a receptor saturating concentration (e.g., >10× the Ki value) of CP-55,940 (10−7 M) or PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) was added to each well and incubated for increasing durations of 0 min, 30 min, 1 hr, 2 hr, 3 hr and 10 hr. After drug incubation, cells were washed three times with 6 ml of serum free HAM’s F-12 K media. Following the last wash, 1 ml of PBS/EDTA was added to each well and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 15 min. Cells were then harvested with cell scrapers and collected into 1.5 ml micro-tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. After centrifugation, PBS/EDTA was removed and cell pellets were stored at −80 °C for future use.

Reduction in CB1 receptor density following chronic drug treatment (e.g., receptor down-regulation) was quantified by competition binding assays as previously described (see Methods 2.5), utilizing cell pellets collected following CP-55,940 or PNR-4-20 exposure. Specific binding of 0.2 nM [3H]-CP55,940 was determined by using 20 µg of CHO-β2-hCB1 and CHO-hCB1-Rx cell pellets, and employing (10−7 M) CP-55,940 to define non-specific binding.

Decrease in CB1 receptor activation of G proteins following chronic drug treatment (e.g., receptor desensitization) was measured by [35S]GTPγS binding assays as previously described (see Methods 2.6), utilizing cell pellets collected following CP-55,940 or PNR-4-20 exposure. Specific [35S]GTPγS binding was determined by using 20 µg of CHO-β2-hCB1 and CHO-hCB1-Rx cell pellets in the absence and presence of (10−7 M) of the full CB1/CB2 receptor agonist CP-55,940.

3.0 In vivo Cannabinoid Tetrad Analysis

PNR-4-20 (1, 3, and 10 mg/ml) and rimonabant (1 mg/ml) were prepared in a vehicle containing 1% EtOH, 7.8% tween-80, and 91.2% saline. Mice were individually injected with a constant volume of 0.1 ml/g with a dose of 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg for PNR-4-20 or 10 mg/kg for rimonabant. All vehicle and drug solutions were sonicated for 15 min prior to administration. As previously described (34), mice were administered an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of PNR-4-20 and tested 35 min later. Mice were tested sequentially for all four measures of the cannabinoid tetrad, in the following order; 1) hypothermia, 2) analgesia, 3) catalepsy and 4) suppression of locomotor activity. Briefly, hypothermia was measured utilizing a digital thermometer (model BAT-12, PhysiTemp, Clifton, NJ) equipped with a Ret-3 mouse probe (model 50314, Stoelting Co., Dale, IL) inserted rectally to a depth of approximately 2 cm. Temperature readings were obtained within 8 sec. Analgesia was measured as tail-flick latency using the EMDIE-TF6 radiant heat apparatus (Emdie Instrument Co., Montpelier, VA). Mice were carefully positioned on the stage of the apparatus, while the tail was extended into a groove to break a photobeam. Starting at time = 0, a timer and radiant heat source directed onto the dorsal surface of the tail, approximately 2 cm from its origin from the body, were initiated. Movement of the tail after the beginning of the trial broke the photobeam, stopped both the heat source and the timer, and ended the trial. To prevent tissue damage, the maximum allowed time of each trial was set to 10 sec. Catalepsy was measured by the horizontal bar test, using a tubular steel bar (0.5 cm in diameter) that was supported 4.0 cm above and horizontal to a covered platform. To begin each trial, mice were placed into a speciesatypical position with hindlimbs on the covered platform and forelimbs on the horizontal bar. Upon placement on the catalepsy bar, a timer was started, and counted until the mouse removed both paws from the bar. The maximum time allowed on the bar was 30 sec. Lastly, locomotor activity was measured using polycarbonate activity boxes (26.67 cm × 20.96 cm × 15.24 cm), in which the bottom of each box was marked and divided into four equally-sized quadrants. Each mouse was placed into a separate activity box, and quadrant crossings (all four limbs crossing one of the boundaries) were scored for 5 min using an overhead video camera. Between experimental observations, boxes were sprayed and wiped with Coverage Plus NPD (Steris Healthcare, Mentor, OH), and dried with paper towels.

3.1 Tolerance to hypothermic effects in Chronically Treated Mice

NIH Swiss were weighed and administered i.p. injections of either saline, 3 mg/kg JWH-018, 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC, or 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 for 5 consecutive days. Rectal temperatures were measured each day (using the same procedure as described earlier in Methods section 3.0) 1-hour after injection of saline, Δ9-THC and JWH-018, and 35-minutes after PNR-4-20 administration. After the 5th injection, animals were subjected to a 7-day washout where no injections were administered. On day 7 of the washout, animals were again injected with the same dose of the same compound they were previously administered for the 5-day chronic study, and were reassessed for drug-induced effects on rectal temperature.

3.2 Rimonabant Precipitated Withdrawal

NIH Swiss mice were chronically administered saline, 3 mg/kg JWH-018, or 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 once per day for 5 consecutive days via i.p. injection. On the 5th day of drug injections, animals received 10 mg/kg rimonabant 75 minutes after the injection of saline or JWH-018, and 50 minutes after the injection of PNR-4-20. As previously described (35, 36), immediately following the rimonabant injection, mice were placed in a circular, transparent glass vessel (radius 4.25 cm, height 16 cm) sealed with a ventilated cover and closely observed for withdrawal signs (front paw tremor, face rubbing and back paw rearing) for 60 min. Scoring the observed withdrawal signs was accomplished by counting the frequency of front paw tremors and recording the duration of face rubbing and rearing behaviors. Between groups of mice, observation vessels were sprayed and wiped with Coverage Plus NPD (Steris Healthcare, Mentor, OH), and dried with paper towels.

3.3 Statistical analyses

GraphPad Prism version 7.03 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was utilized for all curve-fitting and statistical analyses. Each in vitro data point presented in all figures is represented as the mean ± S.E.M. (Standard Error of the Mean) from a minimum of 4 individual experiments. Three-parameter nonlinear regression for one-site competition was used to determine the IC50 for competition receptor binding. IC50 values were subsequently converted to Ki values (a measure of receptor affinity) by the Cheng-Prusoff equation (37). Four-parameter non-linear regression was used to analyze concentration-effect curves to determine the EC50 or IC50 (measures of potency) and Emax or Imax (measures of efficacy) for GTPγS binding and adenylyl cyclase or β-arrestin 2 recruitment, respectively. All dissociation constants and measurements of potency were converted to pKi, pEC50, or pIC50 values by taking the negative log of each value so that parametric tests could be used for statistical comparisons. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups (i.e., dose of PNR-4-20) in the tetrad experiments were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons tests. Multiple ANOVAs within each data set were corrected using a Bonferroni adjustment such that statistical significance was declared at p < .0252-tail. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups in the tolerance and withdrawal experiments were performed using a two-way mixed-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment group serving as the between-subjects factor and test day serving as the within-subjects factor. Dunnett’s or Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons tests (or simple main effects tests in the case of a statistically significant interaction) were performed to compare treatment groups to saline control or for all pairwise comparisons. Last, a one-way ANOVA was performed to compare withdrawal signs between treatment groups, followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons tests. Statistical significance for all measures recorded in the tolerance and withdrawal experiments was declared at p < .052-tail.

Biased hCB1R signaling was determined by comparing the intrinsic activity of agonists to activate G-proteins, inhibit forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation, and recruit β-arrestin 2 in transfected CHO cells. Specifically, transduction ratios [log(τ/KA)] for each test ligand in all assays were calculated from full concentration-effect curves fit by GraphPad Prism (version 6.0h) to the Black-Leff operational model of agonism (38) employing a user defined equation as detailed in Westhuizen et al. (39). In this arrangement of the model, log(τ/KA) is a composite parameter made up of two distinct parameters; KA is defined as the equilibrium affinity constant (KA) and tau is defined as a combination of receptor density and the coupling efficiency of the agonist. In this specific form of the model, the tau and KA parameter values are not the primary endpoint of the fit. The model is expressed in order to produce the unique log(τ/KA) value for each agonist without solving either of the parameters directly. Where indicated, a competitive operational model of bias was used to analyze a subset of data. This was included because it has been shown that, in some cases, this model is able to produce a reduction in the error of the estimated log(τ/KA) values (40). The calculated log(τ/KA) values were used to provide a single parameter value for reported intrinsic activity assessments of each respective test ligand in each assay examined. The full non-biased hCB1R agonist CP-55,940 was used as the reference compound for comparison in all studies.

To calculate a normalized transduction coefficient [e.g., the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio] for a test ligand in each assay, the log(τ/KA) for the reference agonist CP-55,940 was subtracted from the log(τ/KA) for each test ligand of interest, as shown in equation 1:

| (eq. 1) |

The resulting Δlog(τ/KA) ratio for each respective test ligand was next used to determine the relative efficiency or favorability of that compound to evoke a distinct receptor-mediated response when comparing two different functional assays [e.g., the ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio]. This was calculated by subtracting the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio determined for the test ligand in one functional assay, from the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio determined for the same test ligand in a second functional assay, as shown in equation 2:

| (eq. 2) |

Finally, the ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio was used to calculate the bias factor for each test ligand for modulation of the two different functional assays examined, as shown in equation 3:

| (eq. 3) |

4. 0 Results

4.1 IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 bind hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells with high nanomolar affinity

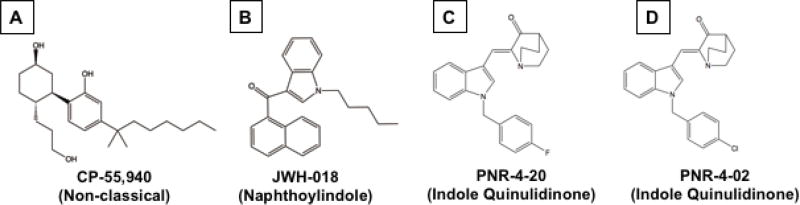

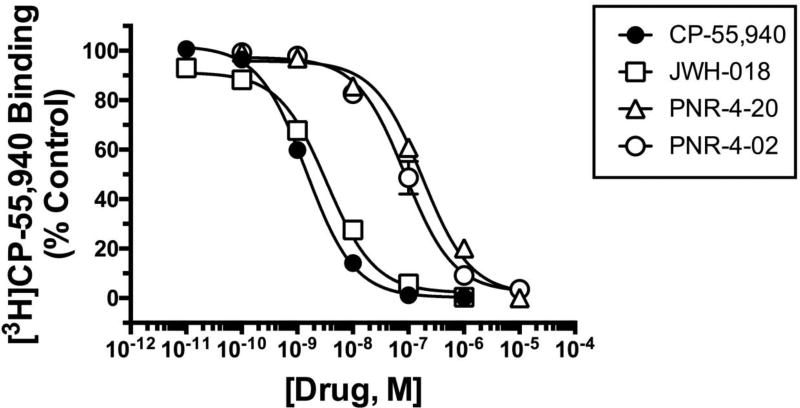

The structures of cannabinoids agonists examined in this study are presented in Figure 1, and represent compounds derived from the structurally distinct non-classical (Fig. 1A; CP-55,940), naphthoylindole (Fig. 1B; JWH-018) and indole quinulidinone (Fig. 1C; PNR-4-20 and Fig. 1D; PNR-4-02) classes (29, 41). Initial competition binding studies, employing the high affinity CB1/CB2R agonist [3H]CP-55,940 (42), were conducted to determine the affinity of the cannabinoid ligands examined (Fig. 2) for hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells. The affinity of all compounds for hCB1Rs are presented as Ki values (Table 1), derived from IC50 values (37) obtained from competition binding curves (Fig. 2). Ki values were converted to pKi values (pKi=−Log[Ki]; Table 1) so that parametric tests could be used for statistical comparisons. All compounds exhibit concentration-dependent and complete displacement of [3H]-CP-55,940, with high affinity for hCB1Rs with a rank order (from highest to lowest) of CP-55,940 = JWH-018 > PNR-4-02 = PNR-4-20. These data indicate that the novel IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 bind with high affinity to hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells.

Fig. 1.

Structures of cannabinoid ligands examined in this study.

Fig. 2.

IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 analogues examined bind hCB1Rs expressed

Table 1.

G protein-dependent and –independent signaling for hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 and CHO-hCB1-Rx cells

|

3H-CP-55,940 Binding |

35S-GTPγS Binding Assay | cAMP Assay | β-Arrestin 2 Assay | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Cell Line | Ligand | pKi | Ki (nM) |

N | pEC50 | EC50 (nM) |

EMAX | N | pIC50 | IC50 (nM) |

IMAX | N | pEC50 | EC50 (nM) |

EMAX | N |

| CHO-β2-hCB1 | CP-55,940 | 8.91±0.04a | 1.26 | 4 | 9.49±0.08a | 0.338 | 1.03±0.06a | 4 | 7.77±0.12a | 19.0 | 1.14±0.14a | 4 | 7.30±0.10a | 54.1 | 1.04±0.17a | 4 |

| JWH-018 | 9.12±0.06a | 3.00 | 4 | 9.25±0.23a | 0.749 | 1.02±0.10a | 4 | 8.82±0.15b | 1.73 | 0.90±0.05a | 4 | 7.17±0.08a | 78.1 | 1.16±0.16a | 4 | |

| PNR-420 | 6.83±0.03b | 159 | 4 | 7.29±0.09b | 53.91 | 1.02±0.10a | 4 | 6.97±0.34a,c | 180 | 1.26±0.10a | 4 | 5.28±0.06b | 5412 | 0.24±0.02b | 4 | |

| PNR-402 | 7.07±0.10b | 73.0 | 4 | 7.66±0.04b | 22.92 | 0.62±0.01b | 4 | 6.56±0.09c | 293 | 1.06±0.07a | 4 | NA | NA | NA | 4 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| CHO-hCB1-Rx | CP-55,940 | 9.07±0.13† | 0.92 | 3 | 8.80±0.14† | 1.80 | 91.0±11.0† | 4 | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ||

| PNR-420 | 7.11±0.13 | 85.1 | 3 | 6.89±0.09 | 130 | 79.3±11.3 | 4 | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | ---------- | |||

Initial studies with PNR-4-20 (30), referred to as compound number 5 in that report, exhibited an affinity of 9.3 nM for mouse CB1Rs. Curiously, in the present study the affinity of PNR-4-20 for human CB1Rs was determined to be 159 nM. In addition to the obvious species difference, differences in batch-to-batch purity of PNR-4-20 and/or vehicles used for drug solubilization might have contributed to the magnitude of the observed differences in the affinity of PNR-4-20 for CB1Rs between studies.

The cannabinoid ligands examined in this study were derived from the structurally distinct non-classical [A], naphthoylindole [B] and indole quinulidione (43) classes. CP-55,940 was employed as a reference ligand throughout this study, exhibiting non-biased full agonist activity at hCB1Rs in all assays examined. G protein-dependent and -independent signaling properties of JWH-018, PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 via hCB1Rs are currently unknown.

in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells with high nanomolar affinity. The affinities (Ki) of CP-55,940 (filled circles), JWH-018 (open squares), PNR-4-20 (open triangles) and PNR-4-02 (open circles) for CB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells were determined by competition binding, utilizing 0.2 nM of the CB1/CB2 agonist [3H]-CP-55,940. Ki values were derived from three-parameter non-linear regression analysis of the binding curves presented. Ki values were converted to pKi values for statistical analyses and are presented in Table 1. Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments.

EMAX and IMAX values are presented as the fraction of the effect produced by the reference agonist CP-55,940.

a,b,cpKi, pEC50, and pIC50 values designated by different letters in the CHO-β2-hCB1 cell line are significantly different from values within the same column; P<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc test.

†pKi, pEC50, and pIC50 values for CP-55,940 in the CHO-hCB1-Rx cell line are significantly different from PNR-4-20 values; P<0.05, student’s t-test.

NA- not applicable: PNR-4-02 was unable to produce sufficient levels of β-arrestin 2 recruitment to allow for quantification of concentration-effect curves.

4.2 PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 potently and efficaciously couple hCB1Rs to G protein-dependent signaling pathways in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells

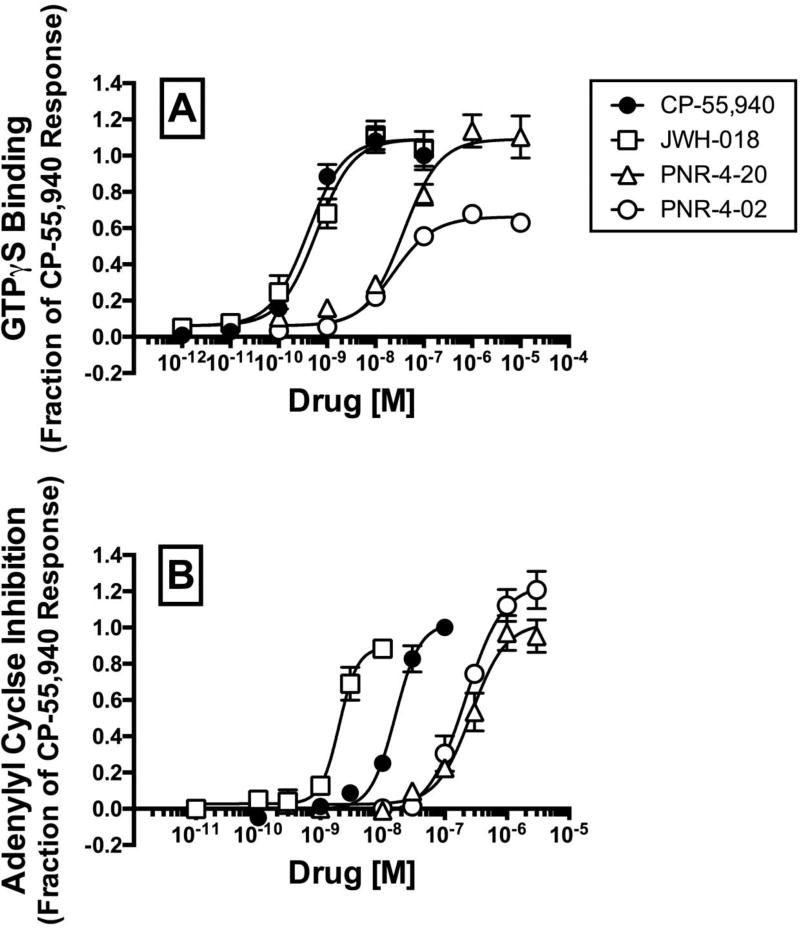

Agonist binding to CB1Rs initiates a number of signaling cascades that occur via both Gi/o protein-dependent and -independent mechanisms (44, 45). G protein-dependent effects arise from agonist stabilization of distinct CB1R conformations that couple to Gi/o proteins, resulting in modulation of the activity of down-stream effectors including K+ channels, Ca++ channels and the enzyme adenylyl cyclase (46, 47). Since all cannabinoid ligands examined (Fig. 1) bind to hCB1Rs with high affinity (Fig. 2), experiments were next conducted to determine the ability of these compounds to activate G proteins, the first step in Gi/o protein signaling pathways (Fig 3A; Table 1). Gi/o protein activity was quantified in membranes prepared from CHO-β2-hCB1 cells incubated with the non-hydrolysable, radioactive GTP analog [35S]GTPγS, and increasing concentrations of each ligand to be examined. Measures of potency (e.g., EC50) and efficacy (e.g., EMAX) were derived from full concentration-effect curves (Fig 3A) and are presented in Table 1. To allow use of parametric statistical analyses, EC50 values were converted to pEC50 values (pEC50=−Log[EC50]). As expected, the well characterized full CB1R agonist CP-55,940 (48) and abused synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 (49) produce similar potent and efficacious increases in [35S]GTPγS binding (Fig. 3A; Table 1). The novel IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 also act as agonists to activate G proteins; however, with decreased potency when compared to CP-55,950 and JWH-018 (P>0.05; Table 1). The rank order of potency for G protein activation is identical to the rank order of affinity for CB1Rs. CP-55,940, JWH-018, and PNR-4-20 act as full CB1R agonists to activate G proteins (e.g., EMAX values of 1.03 ± 0.06, 1.02 ± 0.10, and 1.02 ± 0.10 fractional units, respectively). By contrast, PNR-4-02 exhibits only partial agonist activity in this assay (e.g., EMAX value of 0.62 ± 0.01 fractional units; P<0.05; Table 1) and the fit of PNR-4-02 data to the operational model produces a log affinity (pEC50) estimate of 7.66 ± 0.04. These results indicate that CP-55,940, JWH-018, and the IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 all act as CB1R agonists to activate G proteins in CHO-β2-hCB1 membranes.

Fig. 3.

PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 potently and efficaciously couple hCB1Rs to G protein-dependent signaling pathways in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells.

To provide an additional measure of efficacy for G protein-dependent signaling produced by the cannabinoid ligands examined, the ability of all compounds to modulate activity of the intracellular effector adenylyl cyclase via hCB1Rs expressed in intact CHO-β2-hCB1 cells was measured (Fig 3B; Table 1). Agonist binding to CB1Rs results in activation of Gi/o proteins that then inhibit activity of the downstream effector adenylyl cyclase, resulting in a reduction in levels of intracellular cAMP (11, 50). Consistent with actions of an agonist, and results observed for G protein activation (Fig 3A), CP-55,940 (filled circles), JWH-018 (open squares), PNR-4-20 (open triangles) and PNR-4-02 (open circles) all produce concentration-dependent decreases in forskolin-stimulated intracellular cAMP levels in intact CHO-β2-hCB1 cells (Fig. 3B). Measures of potency (e.g., IC50 values) and efficacy (e.g., IMAX values) derived from the best fit of the concentration-effect curves are presented in Table 1. To allow for use of parametric test for statistical comparisons, IC50 values were converted to pIC50 values (pIC50=−Log [IC50]). Similar to the rank order of hCB1 affinity (Fig. 2) and potency for G protein activation (Fig. 3A), the rank order of potency to modulate adenylyl cyclase activity is CP-55,940 > JWH-018 > PNR-4-20 = PNR-4-02 (P<0.05; Table 1). Interestingly, unlike that observed for G protein activation in which PNR-4-02 exhibits partial agonist activity (Fig 3A), all cannabinoid ligands act as full agonists to modulate adenylyl cyclase activity in intact CHO-β2-hCB1 cells.

To verify that the G protein-dependent effects observed for the cannabinoid ligands examined are due to specific interaction with hCB1Rs, G protein activation and modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity studies were conducted in CHO cells devoid of hCB1Rs, but instead stably expressing human μ-ORs (e.g., CHO-hMOR cells). As expected, in membranes prepared from CHO-hMOR cells, the full μ-opioid agonist DAMGO (51), but not CP-55,940, JWH-018, PNR-4-20 nor PNR-4-02, increases [35S]GTPγS binding (data not shown). Similarly, only DAMGO decreases forskolin-stimulated intracellular cAMP levels in intact CHO-hMOR cells (data not shown). Collectively, these experiments suggest that CP-55,940, JWH-018, PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 all potently and efficaciously activate G proteins and modulate activity of the Gi/o mediated intracellular effector adenylyl cyclase in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells via hCB1Rs.

Two measures of efficacy of cannabinoids ligands examined were used to characterize G protein-dependent signaling via CB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells; [A] G protein activation, and [B] modulation of activity of the downstream effector adenylyl cyclase. [A] Gi/o protein activation was quantified by measuring [35S]GTPγS binding, and [B] modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity was determined by measuring levels of forskolin-stimulated intracellular cAMP production, in the presence of increasing concentrations (10−12 to 10−5 M) of the cannabinoid agonists CP-55,940 (filled circles), JWH-018 (open squares), PNR-4-20 (open triangles) and PNR-4-02 (open circles). All four ligands act as agonists in both functional assays. Four-parameter non-linear regression was used to analyze concentration-effect curves to determine the EC50 or IC50 (measures of potency) and Emax or Imax (measures of efficacy) for GTPγS binding and adenylyl cyclase, respectively. Potency values were converted to pEC50 values to allow use of parametric statistical analyses and are presented in Table 1. Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments.

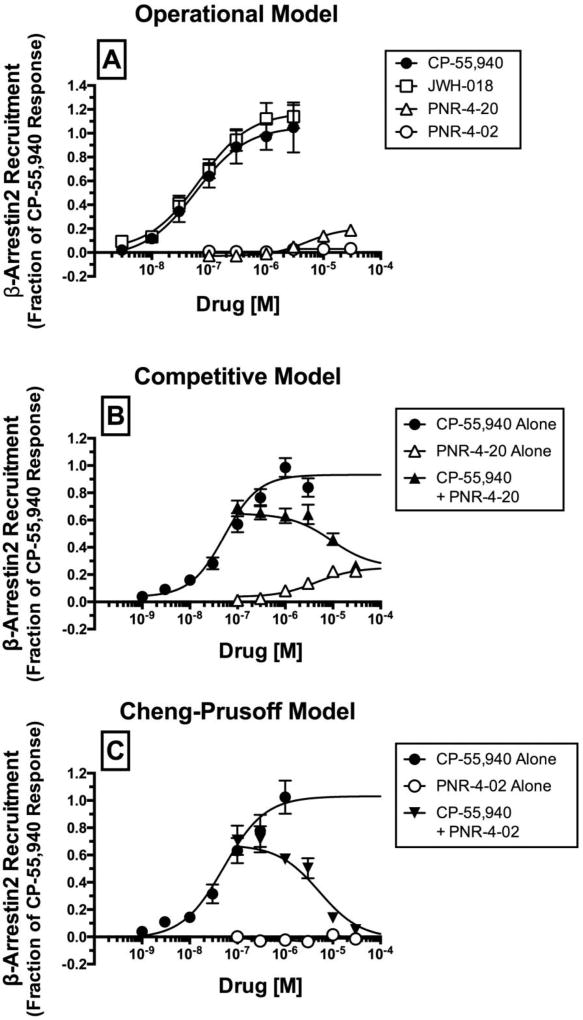

4.3 CP-55,940 and JWH-018, but not PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02, potently and efficaciously couple hCB1Rs to G protein-independent signaling pathways via recruitment of β-arrestin 2 in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells

Functional assessment thus far has revealed that CP-55,940, JWH-018, PNR-4-20, and PNR-4-02 all couple hCB1Rs to Gi/o protein-dependent signaling pathways. Although the standard paradigm for pharmacological assessment of novel hCB1R ligands examines coupling to G protein-dependent signaling pathways, G protein-independent signaling can also be revealed by quantifying the ability of ligands to recruit β-arrestin 2, a proximal scaffolding protein originally associated with GPCR desensitization and down-regulation (13). Agonist recruitment of β-arrestin 2 by hCB1Rs in the present study employed PathHunter™ technology (DiscoverRx Corporation, Fremont, CA) that utilizes enzyme complementation of β-galactosidase fragments fused to hCB1Rs and β-arrestin 2. Specifically, activation of hCB1Rs by appropriate agonists results in recruitment of β-arrestin 2 and formation of a fully functional β-galactosidase enzyme, capable of cleaving a substrate to produce a quantifiable chemiluminescent signal.

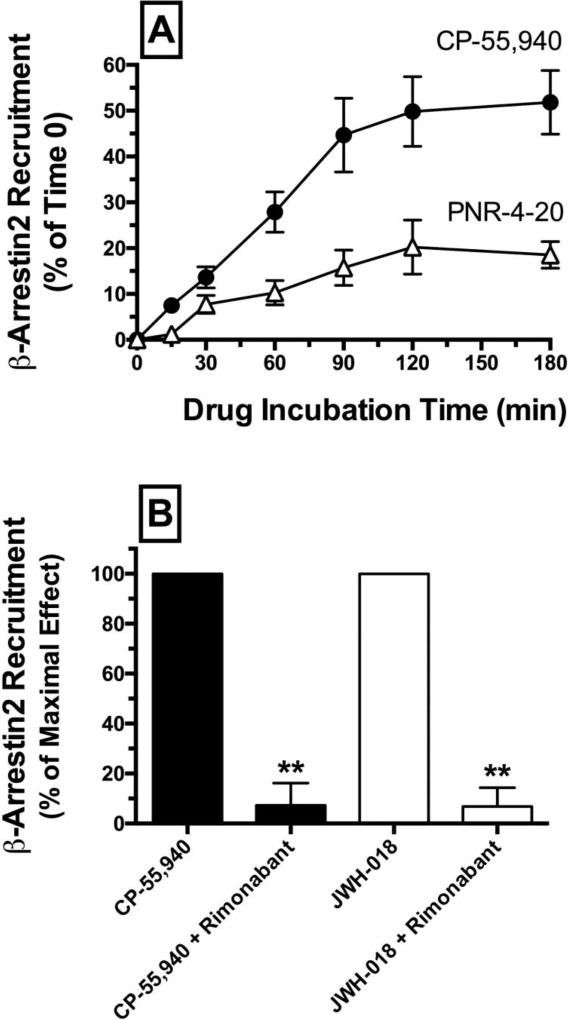

Initial optimization experiments were conducted to determine the time-dependent characteristics of β-arrestin 2 recruitment produced by incubation with the reference agonist CP-55-940 and test ligand PNR-4-20 (Fig. 4A). For these experiments, β-arrestin 2 recruitment was measured following 0 to 180 minute incubation of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells with CP-55,940 or PNR-4-20. Results showed that β-arrestin 2 recruitment produced by both CB1 agonists occurs in a time-dependent manner with maximal effects observed approximately between 90 to 120 minutes. Based on these observations, all other experiments investigating β-arrestin 2 recruitment were conducted 90 minutes following drug administration. To confirm that recruitment of β-arrestin 2 by CP-55,940 and JWH-018 in this cellular model occurs through a hCB1R-mediated mechanism, co-incubation of these CB1R agonists (10−6 M) with the high affinity CB1-selective antagonist rimonabant (10−5 M) completely eliminates β-arrestin 2 recruitment produced by both agonists (Fig. 4C; P<0.01).] (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 produce time-dependent recruitment of β-arrestin 2 in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells via a CB1R-dependent manner.

[A] CHO-β2-hCB1 cells were incubated with the CB1R ligands CP-55,940 (CP-55,940; 10−7 M) or PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) for increasing durations (0–180 minutes). Both ligands produced time-dependent recruitment of β-arrestin 2 with maximal effects reached following 90 to 120 minute incubations. Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments. [B] Co-incubation of CP-55,940 (10−6 M) or a second full CB1R agonist JWH-018 (10−6 M) with the high affinity CB1-selective antagonist rimonabant (10−5 M) completely eliminates β-arrestin 2 recruitment produced by either agonist. **Bar graphs in panel [B] that are designated by asterisks, are significantly different from CP-55,940 or JWH-018 alone, respectively (P<0.01; Student’s t-test).

Results from full concentration-effect curves demonstrate that CP-55,940 and JWH-018 potently (e.g., EC50 values of 54.1 nM and 78.1 nM, respectively) and efficaciously (e.g., EMAX of 1.04 ± 0.17 and 1.16 ± 0.16 fractional units, respectively) recruit β-arrestin 2 in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells (Fig. 5A; Table 1). In marked contrast, the IQD analogue PNR-4-20 recruits β-arrestin 2 with significantly lower potency (e.g., EC50 value of 5412 nM) and efficacy (e.g., EMAX value of 0.24 ± 0.02 fractional units) (Table 1; P<0.05). Furthermore, the second IQD compound examined, PNR-4-02, is unable to produce sufficient levels of β-arrestin 2 recruitment to allow for quantification.

Fig. 5.

CP-55,940 and JWH-018, but not PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02, potently and efficaciously couple hCB1Rs to G protein-independent signaling pathways via recruitment of β-arrestin 2 in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells

CP-55-940 and PNR-4-20 both bind to hCB1Rs with nanomolar affinity (Fig 2; Table 1), yet only CP-55,940 produces efficacious recruitment of β-arrestin 2 (Fig. 5A). If recruitment of β-arrestin 2 by CP-55,940 occurs via interaction with hCB1Rs, then it would be predicted this recruitment should be reduced by co-incubation with PNR-4-20 (Fig. 5B). In fact, it is possible to quantitate this interaction at the shared orthosteric site using a specific form of the operational model (40). With this model, it is possible to produce an accurate mechanistic understanding of the relative efficacy of PNR-4-20 (Fig. 5B; Table 2).

Table 2.

Log(τ/KA) and ΔLog(τ/KA) ratios for cannabinoid agonists at CB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells

|

35S-GTPγS Binding Assay |

cAMP Assay | β-Arrestin 2 Assay (Operational) |

β-Arrestin 2 Assay (Competitive) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Cell Lin | Ligand | Log(τ/KA) | ΔLog(τ/ KA) |

N | Log(τ/KA) | ΔLog(τ/ KA) |

N | Log(τ /KA) |

ΔLog(τ/ KA) |

N | Log(τ/ KA) |

ΔLog(τ/ KA) |

N |

| CHO-β2-hCB1 | CP-55,940 | 9.38a (9.14 to 9.63) | 0.00a | 4 | 7.71a (7.40 to 8.01) | 0.00a | 4 | 7.09a (6.81 to 7.37) | 0.00a | 4 | 7.23a (7.17 to 7.28) | 0.00a | 7 |

| JWH-018 | 9.26a (8.52 to 10.01) | −0.12a (−0.69 to −0.45) | 4 | 8.56b (8.17 to 8.94) | 0.85b (0.63 to −1.0) | 4 | 7.27a (7.20 to 7.34) | 0.18a (−0.15 to 0.51) | 4 | NA | NA | NA | |

| PNR-420 | 7.40b (7.04 to 7.76) | −1.99b (−2.54 to −1.43) | 4 | 6.45c (6.02 to 6.88) | −1.25c (−1.58 to −0.93) | 4 | 4.37b (3.82 to 4.93) | −2.72b (−3.33 to −2.10) | 4 | 4.84b (4.53 to 5.16) | −2.39b (−2.67 to −2.10) | 7 | |

| PNR-402 | 7.53b (7.30 to 7.76) | −1.85b (−2.13 to −1.58) | 4 | 6.73c (6.51 to 6.95) | −0.98c (−1.29 to −0.67) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

A second IQD compound examined, PNR-4-02, was unable to produce sufficient levels of β-arrestin 2 recruitment to allow for quantification (Fig. 5A). It is possible to analyze the competitive nature of this ligand and demonstrate that PNR-4-02 nevertheless binds to CB1Rs with sufficient affinity to antagonize the agonist-mediated recruitment of β-arrestin 2 by CP-55,940 (10−7 M) and completely reverses this response in a concentration-dependent manner by co-incubation with PNR-4-02 (10−7 to 10−4 M) (Fig. 5C). From this analysis, it is possible to produce an affinity value for PNR-4-02 using the Cheng and Prusoff method (37). The log affinity (pKi) of PNR-4-02 produced by this method in the β-arrestin 2 recruitment assay of 5.749 ± 0.092 (Fig. 5C) is strikingly different than the affinity estimate (pEC50) produced from G protein activation of 7.29 ± 0.09 (Fig. 3A; Table 1).

[A] G protein-independent signaling was quantified via employing a β-arrestin 2 recruitment assay measuring complementation of hCB1R- and β-arrestin 2-fused β-galactosidase enzyme fragments that occurs upon agonist activation and emits a chemiluminescent signal. β-arrestin 2 recruitment produced by activation of hCB1Rs by increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−4 M) of CP-55,940 (closed circles), JWH-018 (open squares), PNR-4-20 (open triangle) or PNR-4-02 (open circles) was measured. Four-parameter non-linear regression was used to analyze concentration-effect curves to determine the EC50 (a measure of potency) and Emax (a measure of efficacy) for β-arrestin 2 recruitment. Potency values were converted to pEC50 values to allow use of parametric statistical analyses and are presented in Table 1. Recruitment of β-arrestin 2 produced by CP-55,940 (10−7 M) is decreased in the presence of increasing concentrations (10−7 to 10−4 M) of PNR-4-20 [B] and PNR-4-02 [C]. Log(τ/KA) and ΔLog(τ/KA) ratios values were calculated for test ligands by the operational (38) [A], competitive (40) [B] or Cheng-Prusoff (37) [C] methods and are presented in Table 2. Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments.

4.4 PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 act as highly G protein biased CB1R agonists

The marked differences in potency and efficacy (Table 1; P<0.05) of PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 to modulate G protein-dependent (e.g., G protein and adenylyl cyclase activity) versus G protein-independent (e.g., β-arrestin 2 recruitment) signaling pathways (Figs. 3 and 5; Table 1), suggest that the IQD analogs PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 act as G protein biased CB1R agonists. To establish and quantify the degree of bias produced by the IQD analogues and JWH-018, data derived from the concentration-effect curves (Figs. 3A, 3B and 5A) were fit to a form of the Black-Leff operational model of agonism (38, 52) to provide log(τ/KA) ratios (Table 2). These ratios were used to provide a single parameter value for efficacy assessments of each respective ligand in each assay examined (38, 39). When CP-55,940 was used as the reference compound for comparison in all studies, a normalized transduction coefficient Δlog(τ/KA) was produced in each assay (Table 2) as the log(τ/KA) for the reference agonist subtracted from the log(τ/KA) for each test compound of interest (e.g. JWH-018, PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02). The resulting Δlog(τ/KA) ratio for each respective test compound (Table 2) was used to compare the relative efficiency of that compound to evoke a distinct receptor-mediated response when comparing two different functional assays. The difference in the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio, or ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio for test the agonist, is a direct representation of this comparison (Table 3). This was calculated by subtracting the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio determined for the test compound in one functional assay from the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio determined for the test compound in the second functional assay. Finally, the ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio was used to calculate the bias factor for each compound of interest by the following equation; 10ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio (Table 3).

Table 3.

ΔΔLog(τ/KA) ratios and bias factors for cannabinoid agonists at CB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells

| GTPγS / β- Arrestin 2 (Operational) |

GTPγS / β- Arrestin 2 (Competitive) |

AC / β-Arrestin 2 (Operational) |

AC / β-Arrestin 2 (Competitive) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Cell Line | Ligand | ΔΔLog(τ/ KA) |

Bias Factor |

ΔΔLog(τ/ KA) |

Bias Factor |

ΔΔLog(τ/ KA) |

Bias Factor |

ΔΔLog(τ/KA) | Bias Factor |

| CHO-β2-hCB1 | CP-55,940 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 | 0.0 | 1.00 | 0.0 | 1.00 |

| JWH-018 | 0.30 (−0.20 to 0.81) | 2.0 | NA | NA | −0.67 (−0.97 to −0.36) | 0.21 | NA | NA | |

| PNR-420 | 0.73 (0.09 to 1.36) | 5.4 | 0.40 (0.09 to 0.89) | 2.5 | 1.47 (0.93 to 2.00) | 29.5 | 1.13 (0.7 to 1.56) | 13.5 | |

Bias factors comparing G protein-dependent (e.g., G protein activation and adenylyl cyclase modulation) and G protein-independent (e.g., β-arrestin 2 recruitment) signaling demonstrate that the commonly abused full CB1 agonist JWH-018 produces little CB1R bias for coupling to either of these signaling pathways (Table 3). More interestingly, the model suggests that the IQD analogue PNR-4-20 exhibits bias for both CB1R signaling toward G protein activation (e.g., bias factor of 5.4) and modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity (e.g., bias factor of 29.5), when compared to β-arrestin 2 recruitment. This difference of activity is supported by the observation that the 95% confidence intervals for the ΔΔlog(τ/KA) of each response pair do not overlap the value of zero; a 95% confidence interval overlapping zero is viewed as a balanced agonist (8).

The interpretation of the bias of PNR-4-02 is strikingly more complicated due to the lack of demonstrable agonist activity in the βarrestin-2 recruitment assay. This property results an artificial, undefined minimum value when fit using the operational model and leads to ambiguity when interpreting the relative activity of the ligand. For these reasons, it was reasonable to limit this interpretation by present the difference in affinity constants observed for PNR-4-02 in the systems where affinity could be estimated. A remarkable greater than 100-fold difference of affinity was observed for this ligand between the βarrestin 2 and G protein activation systems. This large difference in affinity is accompanied by PNR-4-02 demonstrating a profound inversion in rank efficacy with both greater and less efficacy than PNR-4-20. The difference in affinity combined with the inversion in rank order efficacy suggest it is unlikely that a simple two-state model is sufficient to explain these results. Taken as a whole, the evidence presented here suggests that the IQD analogues PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 are novel agonists that highly bias CB1R signaling toward G protein signaling over β-arrestin 2 recruitment.

Data derived from the concentration-effect curves presented in figures 3A (G-protein activation), 3B (adenylyl cyclase modulation) and 5 (β-arrestin 2 recruitment) were fit to the Black-Leff operational model of agonism (38) to provide log(τ/KA) ratios, a single parameter measure of intrinsic activity of each respective test compound in each assay examined (38, 39). In the β-arrestin 2 recruitment assay the data was fit without (Figure 5A) and without (Figure 5B,C) the competitive ligand activity included in the analysis. Normalized transduction coefficients [e.g., Δlog(τ/KA) ratios] were determined for test compounds in each assay by comparison with the nonbiased reference CB1R agonist CP-55,940. Each log(τ/KA) and Δlog(τ/KA) value includes the 95% confidence interval for the parameter in order to show the degree of confidence.a,b,c Log(τ/KA) and ΔLog(τ/KA) ratios designated by different letters are significantly different from values within the same column; P<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc test.NA- not applicable: PNR-4-02 was unable to produce sufficient levels of β-arrestin 2 recruitment to allow for quantification of Log(τ/KA) and ΔLog(τ/KA) ratios. Δlog(τ/KA) ratios (see Table 2) were used to determine the relative efficiency or favorability of a given compound to evoke a distinct receptor-mediated response when comparing two different functional assays [e.g., the ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio]. This was calculated by subtracting the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio determined for the test ligand in one functional assay, from the Δlog(τ/KA) ratio determined for the same test ligand in a second functional assay. The resulting ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratios are presented along with the 95% confidence interval, in parentheses. to highlight the degree of confidence these values overlap zero. The specified ΔΔlog(τ/KA) parameters were employed to calculate the bias factor for each compound of interest by the following equation; 10ΔΔlog(τ/KA) ratio (38, 39).Note: PNR-4-02 was unable to produce sufficient levels of β-arrestin 2 recruitment to allow for quantification of ΔΔLog(τ/KA) ratios and bias factors and thus are not included in this table.

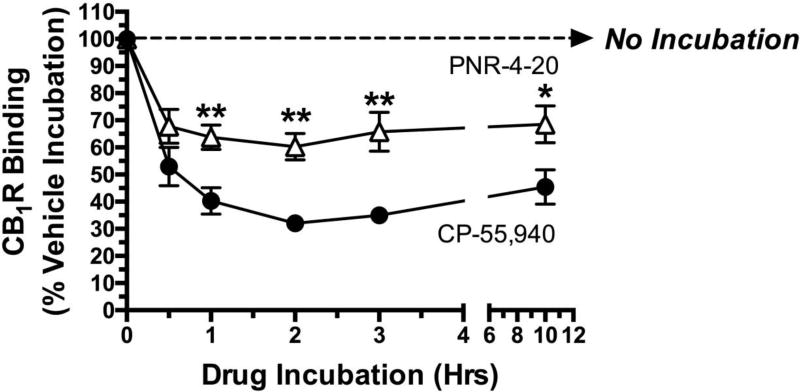

4.5 Chronic exposure of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells to G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 produces less hCB1R down-regulation than prolonged treatment with non-biased agonist CP-55,940

β-arrestin 2 is a signaling molecule that historically has been shown to play an important role in desensitization and down-regulation of many GPCR subtypes following chronic agonist exposure (53). Specifically, upon prolonged agonist binding to GPCRs, translocation of certain G protein receptor kinases (GRKs) results in phosphorylation of specific intracellular serine and threonine residues of activated GPCRs. β-arrestin 2 is then recruited to phosphorylated GPCRs, further interfering with G protein coupling and signaling (e.g., receptor desensitization), and eventually translocating GPCR-β-arrestin 2 complexes to clathrin-coated pits that are internalized for either recycling (e.g., resensitization) and/or removal (e.g., receptor down-regulation) (13). Because PNR-4-20 is a biased agonist that favors G protein-dependent signaling, while producing little interaction of CB1Rs with β-arrestin 2, it was hypothesized that chronic exposure of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells to PNR-4-20 will result in much less CB1R down-regulation than similar prolonged treatment to the non-biased agonist CP-55,940. To test this hypothesis, CHO-β2-hCB1 cells were incubated with receptor saturating concentrations of either CP-55,940 (10−7 M; filled circles) or PNR-4-20 (10−5 M; open triangles) for intervals ranging from 30 min to 12 hours, followed by rigorous washing to remove residual drug (see Methods 2.9) and determination of CB1R density by radioligand receptor binding employing [3H]CP-55,940 (Fig 6). As anticipated following exposure of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells to the full CB1R agonist CP-55,940 (10−7 M), receptor density is reduced by 47 ± 7.1 % after only 30 min, and maximally by 68.0 ± 1.2 % after 2 hrs. In marked contrast, chronic treatment with the G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) reduces CB1R density maximally at 2 hrs by only 39.7 ± 4.9 %. Furthermore, although the general time-course of CB1R down-regulation produced by both drugs appears similar, CP-55,940 produces greater reduction in CB1R density at every time point examined except the 30 min exposure period (P<0.01). The observed differences in CB1R density cannot be explained by potential alteration in the affinity of the radioligand for CB1Rs produced by chronic drug exposure, because 10 hr exposure to either CP-55,940 or PNR-4-20 does not alter the KD of [3H]-CP-55,940 (data not shown). In summary, these experiments indicate that chronic exposure of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells to the G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 produces much less CB1R down-regulation than similar prolonged treatment to the non-biased agonist CP-55,940.

Fig. 6.

Chronic exposure of CHO-β2-hCB1 cells to G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 produces less hCB1R down-regulation than prolonged treatment with non-biased agonist CP-55,940

A receptor saturating concentration of CP-55,940 (filled circles; 10−7 M) or PNR-4-20 (open triangles; 10−5 M) was incubated with CHO-β2-hCB1 cells for increasing time periods (e.g., 0 min, 30 min, 1h, 2h, 3h, and 10 h). Following exposure, cells were rigorously washed with warmed media to remove residual drug and determination of CB1R density by radioligand receptor binding employing [3H]-CP-55,940 (see Methods 2.9). **CB1R binding following exposure to PNR-4-20 at the indicated time periods designated by asterisks, is significantly different from CB1R binding following identical treatment with CP-55,940 (P<0.01; Student’s t-test). Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments.

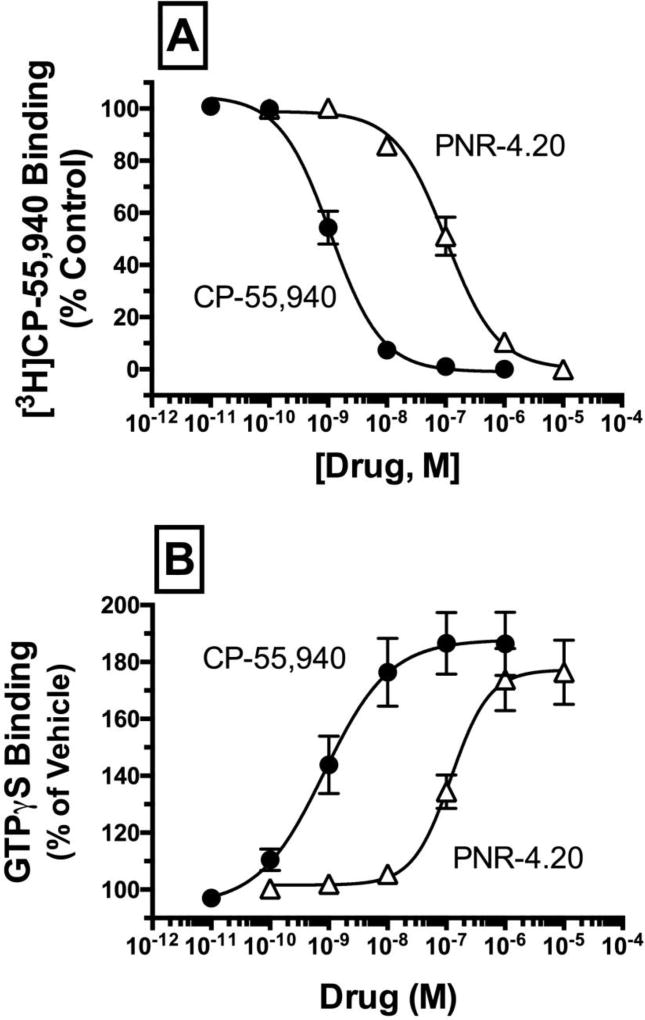

4.6 Similar to observations in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells, CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 also bind to hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells with high affinity and act as full agonists to activate G proteins

Although CHO-β2-hCB1 cells are extremely useful to assess recruitment of β-arrestin 2 by hCB1Rs (Figs. 4 and 5), normal signaling properties of co-expressed hCB1Rs and β-arrestin 2 proteins could be altered because both constructs are tagged with complementary ProLink® β-galactisidase enzyme fragments. Furthermore, the density of hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells is relatively high (e.g., BMAX = 16.8 +/− 2.1 pmole/mg protein, N=4) compared to that expressed in brain (54). Therefore, additional confirmatory studies (Figs. 7 and 8) were conducted in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells, a cell line that stably expresses a more physiological relevant density of non-tagged hCB1Rs (e.g., BMAX = 2.81 ± 0.72 pmole/mg protein, N=3) and native β-arrestin. Initial experiments determined that the affinity of CP-55,940 (filled circles) and PNR-4-20 (open triangles) for hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells are similar to that determined previously in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells (Fig 7A; Table 1). Also as observed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells, both CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 act as full hCB1R agonists in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells, increasing [35S]GTPγS binding in a concentration-dependent manner with high potency and efficacy (Fig 7B; Table 1). CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 fail to alter basal [35S]GTPγS binding in membranes prepared from CHO cells lacking hCB1Rs (e.g., CHO-hMOR cells), thus confirming that G protein activation observed for both compounds is mediated via hCB1Rs (data not shown). The slightly lower potency observed for G protein activation by CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 in CHO-hCB1-Rx relative to CHO-β2-hCB1 cells is likely due to expression of fewer hCB1Rs in this cell line (e.g., BMAX of 2.81 pmole/mg versus 16.8 pmole/mg, respectively). In any case, as observed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells, these data suggest that CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 also bind to hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells with high affinity and act as full agonists to activate G proteins.

Fig. 7.

Similar to observations in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells, CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 also bind to hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells with high affinity and act as full agonists to activate G proteins.

Fig. 8.

Chronic exposure of CHO-hCB1-Rx cells to G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 produces less hCB1R down-regulation and desensitization than prolonged treatment with non-biased agonist CP-55,940

[A] Competition binding studies were conducted to determine affinity (Ki) of CP-55,940 (filled circles) and PNR-4-20 (open triangles) for hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-hCB1-Rx membrane homogenates. [B] The efficacy of CP-55,940 and PNR-4-20 at hCB1Rs expressed in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells was assessed by examining the ability of increasing concentrations (10−11 to 10−5 M) of each compound to increase [35S]GTPγS binding in membrane homogenates. Ki, pKi, EC50, pEC50 and EMAX values derived from non-linear regression of the concentration-effect curves presented and their statistical analyses are listed in Table 1. Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments.

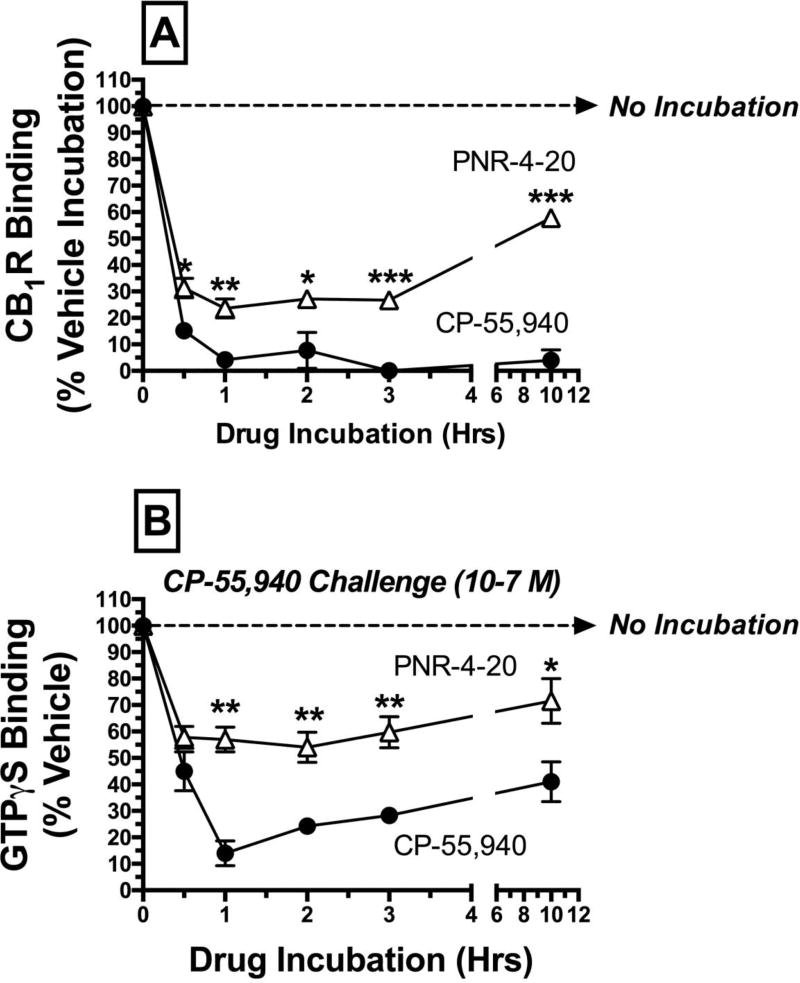

4.7 Chronic exposure of CHO-hCB1-Rx cells to G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 produces less hCB1R down-regulation and desensitization than prolonged treatment with nonbiased agonist CP-55,940

Experiments were next conducted to determine if PNR-4-20 produces similar effects predictive of a G protein biased agonist in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells expressing fewer, non-tagged hCB1Rs and native β-arrestin. Specifically, CHO-hCB1-Rx cells were incubated with PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) or non-biased agonist CP-55,940 (10−7 M) for durations ranging from 0 to 10 hrs, followed by measurement of hCB1R density to detect down-regulation (Fig 8A). As observed in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells, exposure to CP-55,940 decreases hCB1R receptor density by 84.8 ± 3.1 % after only 30 min, and completely eliminates receptor binding at 3 hrs. Also similar to that seen in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells, chronic treatment with PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) only reduces hCB1R density maximally by 76.4 ± 3.6 %, and CP-55,940 produces greater reduction in hCB1R density at every time point examined (P<0.05–0.001). Very interestingly, exposure to PNR-4-20 for 10 hrs results in only 42.2 ± 1.7 % reduction in binding, compared to greater levels of receptor down-regulation at earlier time points, indicating a potential trend towards return of hCB1R density to pre-drug treated levels.

In addition to participating in hCB1R down-regulation, β-arrestin 2 recruitment also decreases the ability of hCB1Rs to couple to downstream signaling pathways, resulting in receptor desensitization (53). Experiments were next conducted to compare the ability of PNR-4-20 and CP-55,940 to produce hCB1R desensitization in CHO-hCB1-Rx cells (Fig 8B). CHO-hCB1-Rx cells were incubated with receptor saturating concentrations of PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) or CP-55,940 (10−7 M) for durations ranging from 0 to 10 hrs, followed by measurement of CP-55,940 (10−7 M) activation of G-proteins via [35S]GTPγS binding. Exposure of CHO-hCB1-Rx cells to CP-55,940 (10−7 M) reduces to the ability of CP-55,940 to maximally activate G proteins by 57.5 ± 7.0% after only 30 min, and maximally by 86.0 ± 4.7% after 1 hr. In contrast, chronic PNR-4-20 (10−5 M) reduces G protein activation by CP-55,940 maximally at 1 hr by only 46.0 ± 5.8%. In addition, prolonged CP-55,940 exposure produces greater reduction in CP-55,940-induced activation of G proteins than chronic PNR-4-20 at every time point examined except the 30 min exposure period (P<0.01). Overall, studies in the CHO-hCB1-Rx cell line, expressing fewer non-tagged hCB1Rs and native β-arrestin, confirm previously presented observations in CHO-β2-hCB1 cells that chronic exposure of cells to the G protein biased CB1R agonist PNR-4-20 produces less hCB1R down-regulation and desensitization than prolonged treatment with non-biased agonist CP-55,940.

A receptor saturating concentration of CP-55,940 (filled circles; 10−7 M) or PNR-4-20 (open triangles; 10−5 M) was incubated with CHO-hCB1-Rx cells for increasing time periods (e.g., 0 min, 30 min, 1h, 2h, 3h, and 10 h). Following exposure, cells were rigorously washed with warmed media to remove residual drug, and [A] CB1R density by radioligand receptor binding employing [3H]-CP-55,940, or [B] maximal G protein activation by CP-55,940 (10−7 M) were determined (see Methods 2.9). *,**,***CB1R binding [A] or G protein activation [B] following exposure to PNR-4-20 at the indicated time periods designated by asterisks, is significantly different from CB1R binding or G protein activation following identical treatment with CP-55,940 (P<0.05, 0.01, 0.001; Student’s t-test). Each data point presented represents the mean ± S.E.M. from a minimum of 4 individual experiments.

4.8 PNR-4-20 acts as an agonist in the cannabinoid tetrad in mice

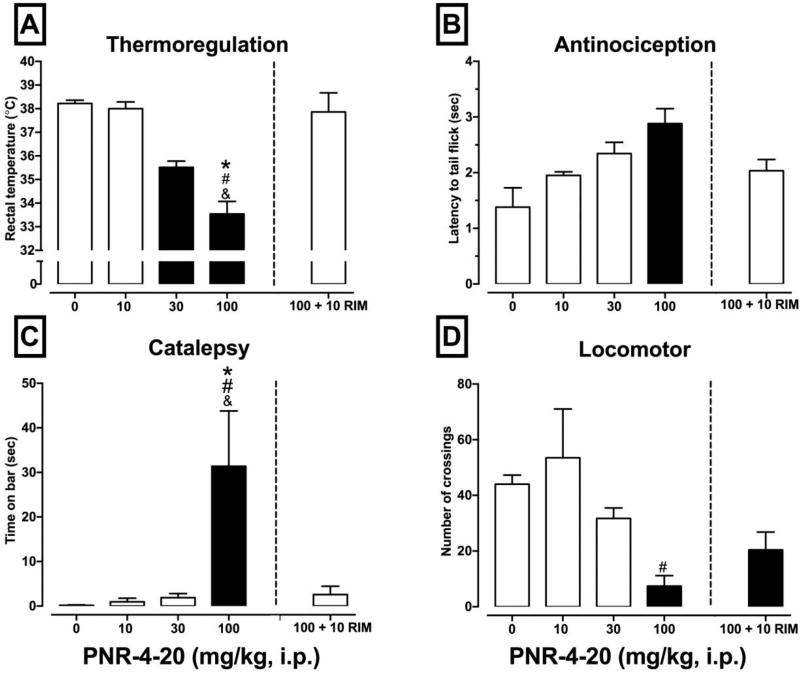

As an initial step toward future development of biased CB1R agonists based on the IQD scaffold, a set of experiments was conducted to evaluate the effects of PNR-4-20 in the cannabinoid tetrad in mice to determine if PNR-4-20 exhibits in vivo cannabimimetic activity. CB1R cannabinoid agonists produce characteristic dose-dependent effects in a set of four biobehavioral endpoints when administered in rodents [e.g., hypothermia, antinociception, decreased locomotor activity, and increased catalepsy], referred to as the cannabinoid tetrad (55). Similar to previous reports (34, 56) in this study NIH-Swiss mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with vehicle, 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 and effects on cannabinoid tetrad endpoints were assessed. Pilot studies used radiotelemetry to assess hypothermic effects of PNR-4-20 at 5-min intervals and found that peak hypothermic effects were observed 35 min after injection (data not shown). As such, a 35 min pretreatment time was used for all subsequent in vivo studies. Figure 9A–D presents the results of the cannabinoid tetrad experiments and CB1R antagonism tests. Statistically significant effects of treatment group were observed on rectal temperature [F(3, 17) = 41.01, p <.001] (Fig. 9A), antinociception [F(3, 17) = 6.07, p = .005] (Fig. 9B), catalepsy [F(3, 17) = 6.34, p = .004] (Fig. 9C), and locomotor activity [F(3, 17) = 6.62, p = .004] (Fig. 9D). Results of the Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons tests for each endpoint are presented in Figure 9A–D. PNR-4-20 exhibits activity consistent with that of a CB1R agonist in all four measures of the cannabinoid tetrad. In regards to the CB1R antagonism experiment, statistically significant effects of treatment group were obtained on rectal temperature [F(2, 12) = 47.03, p <.0001] (Fig. 9A), antinociception [F(2, 12) = 8.14, p <.006] (Fig. 9B), catalepsy [F(2, 12) = 5.74, p <.02] (Fig. 9C), and locomotor activity [F(2, 12) = 15.62, p <.001] (Fig. 9D). Results of the Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons tests for each endpoint are presented in Figure 9A–D. Supporting a CB1R-mediated mechanism of action, co-administration of PNR-4-20 with the CB1R-selective antagonist rimonabant (10 mg/kg) resulted in a significant reversal of the effects of PNR-4-20 on rectal temperature and catalepsy. Together, these experiments indicate that the IQD analogue PNR-4-20 is a highly biased CB1R agonist that exhibits CB1R-mediated biobehavioral effects in mice when administered by the i.p. route.

Fig. 9.

PNR-4-20 acts as an agonist in the cannabinoid tetrad in mice.

NIH-Swiss mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with vehicle, 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 and effects on cannabinoid tetrad endpoints were assessed 35 min following drug administration (57). Specifically, the effects of PNR-4-20 administration were assessed on [A] thermoregulation, [B] antinociception, [C] catalepsy, and [D] locomotor activity. To support a CB1R-mediated mechanism of action, the CB1R-selective antagonist rimonabant (10 mg/kg) was co-administered with 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 (presented to the right of the dashed line in A–D). Filled bars indicate p <.05 compared to vehicle, #p <.05 compared to 10 mg/kg PNR-4-20, &p < .05 compared to 30 mg/kg PNR-4-20, and *p < .05 compared to 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 + 10 mg/kg rimonabant.

4.9 Chronic PNR-4-20 injections result in less tolerance and dependence in mice

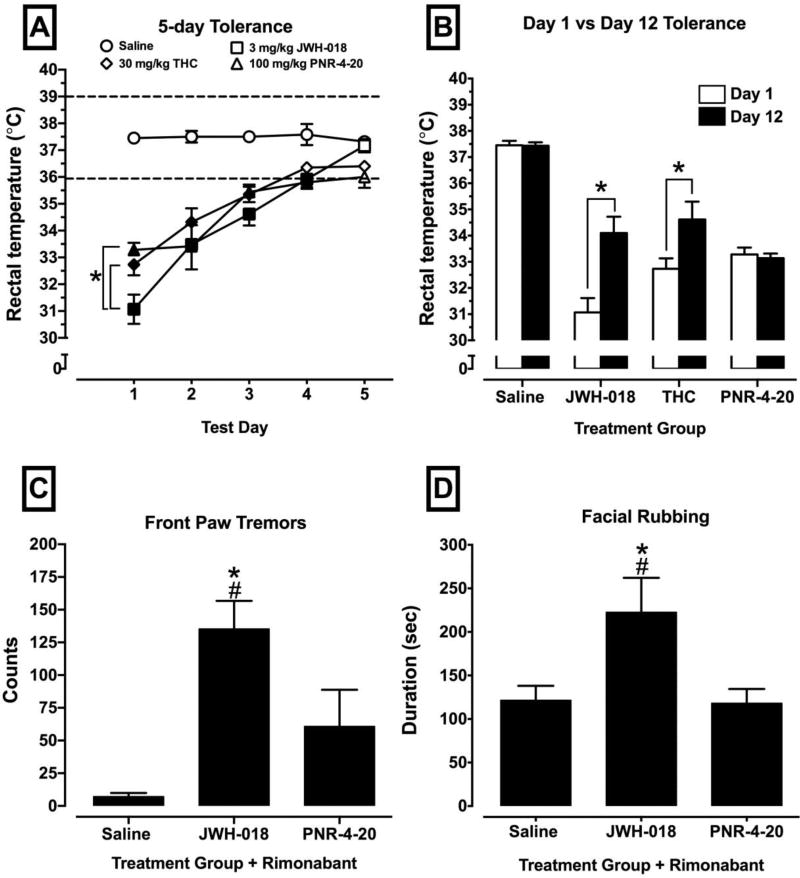

While investigating the in vivo function of PNR-4-20 in mice, additional studies were conducted in order to determine if the in vitro profile of chronic PNR-4-20 exposure is replicated in a chronic dosing animal paradigm. As previously observed, when two separate cell lines expressing the hCB1R were chronically exposed to PNR-4-20 at multiple time points, there was significantly less desensitization and downregulation of the hCB1R when compared to exposure of another full CB1R agonist. As such, drug naïve animals were chronically treated with saline, 3 mg/kg JWH-018, 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC and 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 for 5 consecutive days. Each day, rectal temperature was taken following the allotted drug pretreatment time. Results of Tukey's HSD tests and Dunnett's multiple comparisons tests are presented in Fig 10A–B. All treated animals developed tolerance to cannabinoid-induced hypothermia between days 1 and 5. A two-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant interaction of treatment group and test day [F(15, 95) = 5.31, p < .0001], and statistically significant main effects of treatment group [F(3, 19) = 81.05, p 9003C;.0001] and test day [F(5, 95) = 30.66, p <.0001]. Fig 10A-B presents the results of the tolerance experiments. Following the 5 injections, animals underwent a 7-day “washout” period where drug was not administered. When animals were re-injected with the same drugs on day 7 of the washout, all subjects except animals treated with PNR-4-20 exhibited persistent tolerance to cannabinoid-induced hypothermia when compared to the hypothermic effects observed following the initial injections (Fig. 10B). Because chronic exposure to PNR-4-20 did not result in the development of persistent tolerance following a 7-day washout period, additional studies were conducted to determine if chronic exposure to PNR-4-20 might also result in decreased dependence, as indexed by assessing withdrawal signs following chronic agonist administration and challenge with 10 mg/kg rimonabant. Statistically significant effects of treatment group were observed on front paw tremors [F(2, 14) = 11.73, p = .001] and facial rubbing [F(2, 14) = 4.78, p = .03]. The results of Tukey's HSD multiple comparisons tests are presented in Figure 10C–D. Collectively, animals chronically treated for 5 days with 3 mg/kg JWH-018 then challenged with rimonabant exhibited robust withdrawal signs of front paw tremors and facial rubbing, which are indicative of cannabinoid withdrawal (35, 36, 58). Interestingly, animals chronically injected with PNR-4-20 displayed no significant withdrawal signs when challenged with rimonabant in regard to paw tremors (Fig 10C), facial rubbing (Fig 10D), or rearing behaviors (data not shown), suggesting a reduced dependence liability with this compound. Overall, the in vivo effects observed with PNR-4-20 in regards to tolerance and withdrawal production indicate that cannabinoids that preferentially bias G protein signaling at the hCB1R could reduce the probability of drug-induced adverse effects.

Figure 10.

PNR-4-20 induces less tolerance and reduced antagonist-precipitated withdrawal following repeated exposure.

NIH-Swiss mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with saline, 3 mg/kg JWH-018, 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC, or 100 mg/kg PNR-4-20 and hypothermic effects were assessed following drug administration for five consecutive days [A] and following a 7-day drug-free break [B]. Following the recording of the thermoregulatory effects of test compounds on test day 5, all mice were observed for rimonabant-precipitated withdrawal for a 60 min period (43). Fig 10A: filled symbols indicate statistically significant difference compared to saline within a test day and *p < .05. Fig 9B: *p < .05. Fig 9C–D: *p < .05 compared to saline and #p < .05 compared to PNR-4-20.

5.0 Discussion

The current studies report initial pharmacological characterization of two analogues in a novel structural IQD class that function as highly biased hCB1R agonists. Specifically, it was shown that the IQD compounds PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 elicit G-protein signaling (as measured by G-protein activation and inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation), with transduction ratios proximal to the non-biased full hCB1R agonist CP-55,940. However, in marked contrast to CP-55,940, both PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 produce little to no β-arrestin 2 recruitment. Indeed, the quantitative calculation of bias for the IQD analogue PNR-4-20 compared to the non-biased reference compound CP-55,940 revealed that this ligand favors G protein activation (5.4-fold) and adenylyl cyclase modulation (29.5-fold) over β-arrestin 2 recruitment. Furthermore, a second IQD compound, PNR-4-02, failed to produce sufficient recruitment of β-arrestin 2 to allow for quantification and thus might be anticipated to exhibit greater G protein bias that PNR-4-20. Although the functional selectivity of PNR-4-02 was more complicated to determine, the change in rank order efficacy of PNR-4-02 across multiple assay systems provides striking evidence that the ligand identifies several (more than two) states of the receptor and is also biased toward G protein activation.

As expected due to reduced β-arrestin 2 recruitment, chronic exposure of cells to PNR-4-20 results in significantly less hCB1R desensitization and down-regulation compared to similar treatment with CP-55,940. When tested in mice, PNR-4-20 (i.p.) is active in the cannabinoid tetrad and exerts its biological effects via CB1R activation in a dose-dependent manner. Chronic PNR-4-20 injections produce short-lived tolerance, and no significant withdrawal signs are observed following administration of the CB1R antagonist rimonabant. Finally, studies of a structurally similar analog PNR- 4-02 show that it is also a G protein biased hCB1R agonist when tested in vitro. As reported previously for biased opioid agonists, cannabinoid agonists that bias hCB1R activation toward G-protein, relative to β-arrestin 2 signaling, may produce fewer and less severe adverse effects.

It is interesting to speculate on the activity of these test ligands considering their striking difference in activity between systems. As stated previously, the models are not sufficient to analyze agonists with minimal to no agonist activity in one of the test systems. In this case, it may only be possible to establish occupancy of the test ligand and, based on this occupancy determination, the predictions of a state model can be either accepted or excluded. A two-state model is insufficient to produce a change in rank order efficacy of a series of test ligands between different assay systems (59). This conclusion is distinctly supported, in the case of PNR-4-02, by the demonstration of occupancy and the affinity constant established using the Cheng-Prusoff method (37). Together these avenues of evidence indicate that PNR-4-02, and PNR-4-20, identify distinctly different states of the receptor in the spectrum of functional responses measured.

Current clinical use of cannabinoids is limited and underdeveloped (60), emphasizing a critical need for discovery of novel drugs acting via hCB1Rs that target beneficial signaling pathways, while limiting adverse effects (12, 21, 61). As such, development of biased hCB1R agonists for future therapeutic use holds tremendous promise. Biased ligands acting at several GPCR classes are in various stages of drug development, with some in clinical trials for a variety of disease states that are generating encouraging results. For example, a G protein biased μ-OR agonist (TRV130) produces potent and efficacious analgesia (due to G protein-dependent signaling), while exhibiting significantly less μ-OR mediated respiratory depression and gastrointestinal dysfunction (due to reduced G protein-independent signaling via β-arrestin 2 recruitment) when compared to morphine (15). Biased ligands acting at several other GPCRs, including δ-opioid (16, 62), κ-opioid (17), angiotensin II type I (63), serotonergic (64–66) and β-adrenergic type I and II receptors (67, 68) are also being characterized. These studies investigating biased signaling at GPCRs other than cannabinoid receptors, identify an important gap in our knowledge that could be used to advantage in the preclinical development of similar compounds that specifically interact with cannabinoid receptors (16). Therefore, discovery of biased hCB1Rs agonists derived from the novel IQD scaffold reported herein represents a significant and novel approach towards the development of safe and efficacious cannabinoid drugs for clinical use.

The present studies reveal that PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02, two analogues belonging to a novel class of cannabinoid ligands known as the IQDs (29, 30), are highly G protein biased agonists at hCB1Rs. When compared with non-biased hCB1R agonists CP-55,940 and JWH-018, PNR-4-20 and PNR-4-02 exhibit similar efficacy for coupling hCB1Rs to G protein-dependent signaling pathways, while drastically differing from these agonists in eliciting β-arrestin 2 recruitment via hCB1Rs. Studies examining hCB1R down-regulation and desensitization in response to prolonged exposure to hCB1R biased agonists focused on PNR-4-20, because this analogue acts as a full agonist in all assays examined. Comparing agonists with similar efficacy (to avoid potential confounding effects) is a common approach employed by many studies characterizing the pharmacological actions of biased agonists acting at other classes of GPCRs (15, 17,62, 67, 68). However, it should be noted that while PNR-4-02 acts as a partial agonist for G protein activation, it exhibits full agonist activity for modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity. The full agonist activity of PNR-4-02 observed in the adenylyl cyclase assay is likely because the endpoint being measured (e.g., forskolin-stimulated cAMP production) is an amplified response, occurring downstream relative to G protein activation (the first step in the signaling cascade). In any case, the observed partial, as opposed to full, agonist activity of PNR-4-02 at hCB1Rs might actually present a potential therapeutic advantage for the development of drug candidates in this structural class. The partial hCB1R agonist properties of Δ9-THC (the primary psychoactive component in cannabis) have been proposed to potentially result in fewer and less severe adverse effects associated with marijuana use than those produced by full hCB1R agonist synthetic cannabinoids present in abused K2/Spice products (69). Therefore, development of biased hCB1R partial agonists might ultimately be found to improve the safety profile of these novel cannabinoid receptor ligands.