Abstract

Aims

To identify how efforts to control the diabetes epidemic and the resulting changes in diabetes mellitus, type II (T2D) incidence and survival have affected the time-trend of T2D prevalence.

Methods

A newly developed method of trend decomposition was applied to a 5% sample of Medicare administrative claims filed between 1991 and 2012.

Results

Age-adjusted prevalence of T2D for adults age 65+ increased at an average annual percentage change of 2.31% between 1992 and 2012. Primary contributors to this trend were (in order of magnitude): improved survival at all ages, increased prevalence of T2D prior to age of Medicare eligibility, decreased incidence of T2D after age of Medicare eligibility.

Conclusions

Health services supported by the Medicare system, coupled with improvements in medical technology and T2D awareness efforts provide effective care for individuals age 65 and older. However, policy maker attention should be shifted to the prevention of T2D in younger age groups to control the increase in prevalence observed prior to Medicare eligibility.

Keywords: Diabetes, Elderly, Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is a chronic disease of the endocrine system that leads to multiple complications and increased risk of early death1. The prevalence of T2D has more than doubled globally and is on the rise in the U.S.2–4 Its prevalence among non-institutionalized U.S. adults aged 20+ increased from 5.5% in 1988–1994 to 9.3% in 2005–20105, and older populations (aged 65+) are affected more than any other group6. The prevalence probability of a disease is a fundamental epidemiologic characteristic that can be estimated from survey, medical record, or administrative claim data. At the same time, disease burden forecasts and inferences made on the basis of these probabilities can be misleading because the observed change in disease prevalence results from two simultaneously occurring processes: changes over time in disease incidence and patient survival. These processes are the targets of specific health interventions aimed at either reducing disease incidence, increasing survival, or both. However, even if such health interventions are highly effective and have no adverse trade-off effects, the resulting improvements in population health may not translate into lower disease prevalence. This is due to the underlying relationship between incidence, prevalence, survival, and population health. Both a decrease in incidence and an increase in survival will improve population health. However, while lower incidence decreases disease prevalence, better survival increases it. The ability to partition out the direction and magnitude of each of these components from the overall trend in observed prevalence will assist the medical community in assessing the effect of efforts aimed at controlling the diabetes epidemic.

The analysis in this study is based on a recently-developed methodological approach7 that allows for the partitioning of trends in observed disease prevalence into their components as well as the evaluation of the direction and strength of the effect each component has on the overall change. In this paper we expand this approach to obtain a clear interpretation of obtained partitioning strength. Medicare data are used to estimate models for age- and time patterns of the components: T2D prevalence at 65, incidence after 65, and survival of both groups of patients. The results provide a quantitative basis for the identification of how efforts to control the diabetes epidemic and resulting changes in T2D incidence and survival have affected the time-trend of T2D prevalence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A 5% sample of over 5 million beneficiaries enrolled in the U.S. Medicare social insurance program between 1991 and 2012 was used in this study. Data is provided on services paid for by either Medicare Part A (facility-based services) or Medicare Part B (professional services) as well as demographic and enrollment information. Individuals below the age of 65 were excluded as Medicare data is only nationally representative of individuals age 65+, the age of eligibility for the majority of the Medicare population. Dates of birth and death (where applicable) were drawn from the Medicare denominator file. A diagnosis of T2D was identified by the presence of two inpatient, outpatient and/or private physician practice claims with an International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision Clinical Modification code of 250.xx made within 180 days of each other. This approach has been used successfully in previous studies8–10. The date of diagnosis was used to evaluate the age-specific incidence rate in one-year groups. Empirical prevalence was evaluated by counting individuals who had at least one episode of medical care with a claim for T2D over the last 12 months. Age adjustment was based on the standard U.S. population for the year 2000. Annual percent changes (APC) for T2D prevalence were evaluated empirically and aggregated as the mean APC for each individual year.

The partitioning approach developed in this study is based on an explicit representation of prevalence at ages 65+ with minimal simplifying assumptions. The resulting formulae for age-specific and age-adjusted prevalence for ages 65+ are:

| (1) |

where P(y) is the age-adjusted prevalence of a disease at time y, x is age, p(x) is the density of age distribution in a standard year, τ and yd = y − x + τ are age and time of disease diagnosis, y0 = y − x + x0 is the year when an individual reached age 65 (the age of Medicare eligibility: x0 = 65). Four functions on the right hand side of eqn. (1) are i) P(x0, y0), the prevalence at the beginning of the observation period, ii) S̄r (x − x0, x0, y0), the relative survival function of individuals who had the disease at 65, iii) I(τ, yd), the incidence rate at age τ, and iv) , the relative survival function of individuals diagnosed at yd.

The mathematics involved in the derivation of the formulas for the partitioning of the time trends are given elsewhere (Supplementary Digital Content Appendix) – here we present the conceptual framework. The probability of being prevalent at age x requires being incident at an earlier age τ τ, τ ≤ x and having survived longer than x − τ. This statement is true for a cohort but not directly applicable to the current-population epidemiologic functions we usually deal with in epidemiology such as disease prevalence, the incidence rate, and survival functions. The transformation of cohort-specific formulae to formulae involving the current-population functions results in a compact expression for prevalence in which these functions are aggregated in the form of the relative survival function defined as the ratio of survival probabilities of patients with the disease to the survival probabilities in the general population. Integration over all ages of diagnosis results in the formula for age-specific rates presented in eqn. (1). Two terms (with and without the integral) represent two groups of individuals: those diagnosed before and within the period of observation in the available data. Integration of age-specific prevalence over all ages results in the age-adjusted formula for the prevalence observed in a specific year y.

The time trend in P(y) is determined by trends in prevalence at x0, the incidence rate, relative survival after disease onset, and the proportion of patients with the disease at x0. Formally the time trend is defined as the derivative of P(y) with respect to y or as the annual percent change. The explicit calculation of this derivative results in:

| (2) |

Thus, the time trend is determined through four terms within the brackets of eqn. (2) representing the partitioning of time trends in the prevalence rates:

| (3) |

where the four terms on the right hand side correspond to the four contributions to age-adjusted prevalence associated with trends in: i) prevalence at x0, ii) the probability of relative survival of prevalent individuals at x0, iii) the incidence rate, and iv) the probability of relative survival after diagnosis.

Prior to partitioning analysis, the models for the above four components have to be parameterized and estimated. Since each component is expressed in terms of the derivatives of the incidence and relative survival functions with respect to time, explicit analytic parameterization for all functions is used. This allows us to avoid dealing with possible numeric instabilities that occur when derivatives are evaluated numerically, and ultimately improves the accuracy of our modeling approach. Specific parameterizations for the incidence rate (linear models in respect to both in age and time8,11,12) and relative survival (Weibul models for survival time with coefficients dependent on time linearly, and age quadratically13,14) were chosen based on empiric analysis of the data and prior studies. Model parameters were then estimated using least squares for incidence and a likelihood-based approach15 for relative survival. B-splines were used to fit the time pattern of initial prevalence. This allows for the calculation of derivatives explicitly without the use of additional simplifying assumptions.

Measures of uncertainty for the approach were estimated using non-parametric bootstrapping by the evaluation of the standard errors and means of 10 resampled (with replacement) datasets drawn from the original data.

RESULTS

The prevalence of T2D in older U.S. adults has increased at an average annual percentage change of 2.31% in the 1991–2012 period. Most of this growth occurred in 2000–2003 (average annual percentage change up to 5.58%). Over the last decade, this increase slowed to an average annual percentage change of 1.57%. Time patterns of the empirical estimates of age-adjusted prevalence are shown (Figure 1) together with prevalence obtained using the partitioning methodology (eqn. 1). As expected from model design the calculated T2D prevalence is higher than that given by the empirical data. Prevalence of T2D at the time of data entry (age 65) has increased from 8% in 1992 to 14% in 2005 with a subsequent leveling-off (Figure 1). The B-spline-based model (thick/thin solid line) demonstrates excellent predictions of the empirical data points (filled squares/circles).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of T2D at age 65: empiric estimates (filled squares/circles) using Medicare data and the B-spline model (thick/thin solid line)

Age- and time-patterns of the T2D incidence rate are shown in Figure 2. The post-65-year-old annual incidence of T2D increases with time from 1995 (1.6%) to 2008 (2.1%) and declines thereafter reaching 1.4% in 2012. The linear smoothing model shows (Figure 2) an overall decline (bt < 0) which is largely caused by data-points close to the boundary of the observational period.

Figure 2.

Incidence rate of T2D: age patterns for selected years (1993, 2000, and 2012) of diagnosis (left plot) and year-at-diagnosis patterns for specific age groups (70–79, 80–89, and 90–100 years old) (right panel). The parameters for the incidence model were estimated as b0 =0.019, bt =−0.00013 year−1, a0 =−0.00011 year−1, at =1.4E-6 year−2.

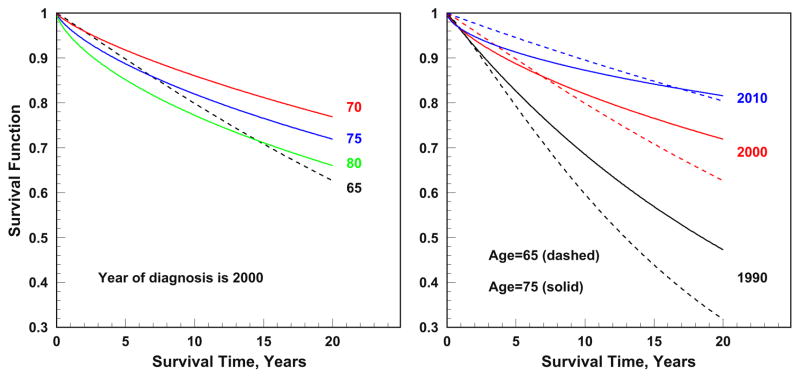

The parameters of the relative survival functions are estimated separately for models of relative survival after disease onset and relative survival of individuals prevalent at data entry. In comparison to individuals reaching age 65 T2D-free, those who had T2D at data entry demonstrated a higher short-term but lower long-term relative survival probability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relative survival functions for patients with T2D for selected ages (65, 70, 75, and 80) and years at diagnoses (1990, 2000, and 2010). Dashed lines show relative survival for individuals prevalent at age 65.

The partitioning of the estimated trend in prevalence (Figure 4; right panel) shows that T2D prevalence increases with time because of i) increasing number of individuals that are already prevalent at age 65, ii) better survival among T2D patients who had the diseases diagnosed before the age of 65, and iii) better survival among patients whose T2D onset was after age 65. Only lower incidence rates in the post-65 Medicare population acted to drive the prevalence down. The relative impacts of these effects remained consistent over time (Table 1). For example, in 2000, T2D prevalence at age 65 accounted for 43.6% of the overall prevalence trend, survival of patients with T2D diagnosed before and after age 65 accounted for 18.3% and 50.7%, respectively, and post-age-65 T2D incidence accounted for −12.6% (the contribution is negative, because changes in incidence resulted in reduction of T2D prevalence). By 2010, contributions of these components changed to 52.3%, 28.3%, 42.9%, and −23.4%, respectively. In summary, the rising T2D prevalence in the U.S. was driven primarily by higher prevalence at age 65 and improved patient survival; the effect of a decrease in incidence, observed over the same period, was unable to overcome this general tendency.

Figure 4.

Time trends of age-adjusted prevalence of T2D represented by b = P′(t)/P(t) where P(t) is age-adjusted prevalence at time t (labeled as “Total, b”) and its partitioning.

Table 1.

Relative strengths of partitioning components and measures of uncertainty.

| 1992 | 1994 | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Relative strength of partitioning components* | |||||||||||

| Prevalence at 65 | 42.3 | 42.2 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 43.6 | 48.4 | 52.1 | 54.1 | 53.9 | 52.3 | 53.5 |

| Survival at 65 | 14.7 | 15.4 | 16.9 | 18.0 | 18.3 | 18.4 | 19.0 | 20.6 | 23.7 | 28.3 | 32.3 |

| Incidence | −9.0 | −9.6 | −10.8 | −11.9 | −12.6 | −13.2 | −14.2 | −15.9 | −18.9 | −23.4 | −27.7 |

| Survival post 65 | 52.1 | 52.0 | 54.0 | 54.0 | 50.7 | 46.4 | 43.0 | 41.2 | 41.4 | 42.9 | 41.9 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Panel B: Measures of uncertainty** | |||||||||||

| Prevalence | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Total trend | 1.63 | 1.56 | 1.27 | 1.01 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.73 |

| Prevalence at 65 | 4.12 | 3.98 | 3.50 | 2.84 | 2.29 | 1.80 | 1.29 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 1.23 |

| Survival at 65 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| Incidence | 0.84 | −0.75 | −0.69 | −0.66 | −0.65 | −0.65 | −0.65 | −0.66 | −0.66 | −0.67 | −0.67 |

| Survival post 65 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.53 |

Relative strengths of partitioning components estimated as Ti/b·100%, where i = p0, S̄, inc, S

Uncertainty calculated as standard error/mean3100% with standard errors and means estimated over 10 resampled datasets

Bootstrapping (Table 1) shows that the sampling uncertainty estimated as the standard error of ten calculations based on resampled datasets is less than 1% with respect to the estimated prevalence, total trend, and partitioning components. An exception is the contribution of prevalence at 65 for which uncertainty reaches 4% in the beginning of the study period.

DISCUSSION

At its outset, the threat that the persistent global rise in T2D incidence would pose to population health was not immediately recognized16. However, once the problem was ascertained, it was targeted through a number of strategies aimed at prevention, treatment, and disease management. The partitioning7 and subsequent analysis of T2D prevalence into its determinants provides important data on the effects (both beneficial and adverse) that these strategies have had on reducing the burden of T2D over time. In this study, we used Medicare data to partition out the effects of changes in T2D incidence and survival on the time-trend of T2D prevalence. The existing trend in T2D age-adjusted prevalence for individuals aged 65 and above is largely the result of four temporal effects: increased prevalence of T2D prior to the age of Medicare eligibility, reduced T2D incidence after 65, and increased T2D-specific survival both for individuals prevalent at age and diagnosed after age 65.

The partitioning formula (1) developed in this study is exact. It involves integration over age at diagnosis for age-specific prevalence and additional integration over all ages to obtain age-adjusted rates. Each component (post-65 incidence and relative survival as well as prevalence and relative survival of individuals with T2D at age 65) was modeled using a model allowing for explicit derivation. The partitioning model provided time patterns of age-adjusted disease prevalence that are higher than T2D prevalence estimated empirically. This is an expected result since empirical estimates only count individuals who had at least one episode of medical care with a claim for T2D over the last 12 months while our model represents the true prevalence by counting all individuals who have ever had a verified diagnosis of T2D in their records. The time patterns of both the empirical and theoretical curves are in agreement with recent reports3–5,17 on trends in the prevalence of T2D.

The time trend of disease prevalence is represented by the derivative of the expression for disease prevalence obtained using the framework of the partitioning method. We found that although the prevalence of T2D increases over time, the speed of this increase is slowing down, that is the derivative is positive, but its value goes down with time. Derivatives of the expression for prevalence have four terms that can be interpreted as contributions of the respective components to the total trend. The sum of these four terms exactly equals the total prevalence trend; and therefore, we can talk about the fractions of the total trend explained by each of the components. We found that the most important contributions were from increased prevalence at 65 (adverse effect) and improved survival for those diagnosed after age 65 (beneficial effect). Both contributions decrease with time and give similar contribution (45–55%) to the total prevalence trend. The contributions of disease incidence and survival of individuals diagnosed before age 65 are both beneficial with stable absolute values over time. However, as the total trend decreases, the relative contributions of these effects increase over time. Improved survival in patients diagnosed with T2D was the primary positive driver behind the increase in T2D prevalence. This reflects the improvements over time in treatment effectiveness, as well as the overall ability to control the progression of diabetes, its complications, and diseases for which diabetes is a risk factor. One important element of controlling the diabetes epidemic in the U.S. has been the development of standards of care such as those published by the American Diabetes Association.19 These guidelines provide medical professionals with current, evidence-based standards on medical screening, medication use, along with behavioral and other measures aimed at managing the progression of T2D. Adherence to these standards, which due to their comprehensive nature essentially serve as a proxy for the overall ability of the U.S. health system to manage the diabetes epidemic, has been shown to reduce the risk of many complications and delay mortality in elderly individuals affected by the disease.20–22 Our analysis shows that the increase in survival was observed in both individuals newly diagnosed post-age-65 and individuals already diagnosed with the disease at time of Medicare eligibility. Furthermore, the relative strength of improved survival in the latter category of individuals almost doubled over the study time-period (Figure 4). This likely reflects the effect of disease duration; i.e. individuals diagnosed prior to Medicare eligibility can be reasonably assumed to have been living with the disease for longer periods of time and therefore have a higher chance to experience T2D-related adverse health effects and would therefore receive more relative benefit from improvements in T2D management. Together these trends are indicative of the ability of the U.S. healthcare system to delay the adverse health outcomes associated with T2D with increasing effectiveness.

Assessing the effect of incidence of T2D is less straightforward. Although time pattern of the incidence rate shows fluctuations, the trends demonstrate the point of change in 2008 found in a previous study3 based on the National Health Interview Survey and do not contradict findings of other studies11,18,23 on the subject. The effect of the fluctuations is not an essential part of the overall trend. Therefore, we used a linear model to smooth these fluctuations. A linear model was chosen because it does not contradict observed patterns and can be used to obtain estimates of incidence in regions which are necessary to calculate integrals in (eqn. 1) as well as regions where incidence cannot measured or can measured but with biases or systematic uncertainties. These regions are: i) before 1991, ii) just after 1991 for all ages, and iii) close to age 65 for all years. Applying the linear model to observed rates showed that the post-age-65 incidence of T2D has been going down over the study period. Sensitivity analysis showed that the decreased rate obtained using this model is largely due to the periods of 1992–1995 and 2008–2012. If individuals with less than 3 years of enrollment are excluded from the analysis (this restriction causes the analysis to start in 1994), the decreasing pattern and the effect of incidence on overall trend identified in the main analysis persists.

The relative strength of the incidence rate to the overall trend in prevalence is small (Figure 4) and is overpowered by the second strongest identified effect (and the only adverse effect); an increase in T2D prevalence at 65, i.e., prior to Medicare eligibility (Figure 1). Prevalence at 65 rapidly increases between 1998 and 2003 but shows little change of the past 10 years. The latter could be a reflection of decreased incidence of diabetes after 2008 first reported in3 and observed in our study (Figure 2). Since the increase in the numbers of detected cases both before and after the age of 65 is accompanied by universal improvement in T2D survival, the observed dynamics of the trends in incidence before and after age 65 could be due to improvements in disease awareness and screening. This potential effect is observable in Medicare data through two processes: i) the increase in prevalence prior to Medicare eligibility, and ii) the decrease in the incidence after Medicare eligibility. In both cases, improvements in disease awareness and screening would act to decrease the severity of the disease and improve survival. The latter effect is observed in our study.

To better understand the observed trends of T2D and its partitioning, we need to consider the dynamics in the fractions of undiagnosed cases observed in some studies. The results of several studies17,24 can be summarized in a conclusion that in the U.S. up to 40% of individuals with T2D have not received a diagnosis in 2000. Since 1997, the ADA has recommended T2D screening for individuals age 45+ at least every 3 years18. Furthermore, more and more other health conditions require screening for T2D by virtue of it being a known risk-factor25. Due, in part, to these efforts the proportion of diabetes cases that are undiagnosed has dropped over the past 20 years, with the largest drop observed among individuals age 65+4. However, this drop is due largely to the increase in the total number of cases and only to a small extent due to the reduction in the number of undiagnosed cases: the prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes remained almost stable and only a minor tendency for its reduction is detected at ages 45–64. These tendencies are consistent with the inferences made with the help of partitioning analysis performed in this paper: although the diabetes epidemic is still a serious health concern, a considerable proportion of the observed trends in T2D prevalence is likely due to an increase in diagnosis at earlier stages and improvements in the care that follows26. Without further research, it is difficult to tell to what extent the overall growth of T2D prevalence is due to beneficial (i.e. early diagnosis and improved care) vs. adverse (i.e. real growth in the number of T2D cases) causes.

In the future, as treatment improves, and screening continues to proliferate, more previously undiagnosed cases will be identified (increasing incidence), at lower severity stages (increasing survival), and patients will receive better and more individualized treatment (increasing survival). This is expected to lead to a continued increase in T2D prevalence even in the case of the cessation of the actual diabetes epidemic and the increase will be observed until either a cure is developed, or the pool of undiagnosed individuals shrinks to insignificant levels. This study has shown that T2D survival and T2D incidence after the age of Medicare eligibility have improved over the 1992–2012 period. Prevalence of T2D at age 65, however, has not. This suggests that in the continuing fight with the diabetes epidemic more attention should be paid to T2D prevention at younger age-groups.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

All-age T2D survival and post-age-65 T2D incidence have improved over 1992–2012.

Pre-age-65 incidence of T2D still poses a challenge.

Emphasis of T2D interventions should be shifted to younger age groups.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (grant R01-AG017473, R01-AG046860, and P01-AG043352). The sponsors had no role in design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, preparation, review, approval of the manuscript, nor decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors have no conflict(s) of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Huang ES, Laiteerapong N, Liu JY, John PM, Moffet HH, Karter AJ. Rates of complications and mortality in older patients with diabetes mellitus: the diabetes and aging study. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(2):251–258. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus—present and future perspectives. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2012;8(4):228–236. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geiss LS, Wang J, Cheng YJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence trends for diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79 years, United States, 1980–2012. Jama. 2014;312(12):1218–1226. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selvin E, Parrinello CM, Sacks DB, Coresh J. Trends in prevalence and control of diabetes in the United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2010. Annals of internal medicine. 2014;160(8):517–525. doi: 10.7326/M13-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Control CfD, Prevention. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. National diabetes statistics report, 2014. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akushevich I, Yashkin A, Kravchenko J, et al. Theory of partitioning of disease prevalence and mortality in observational data. Theoretical Population Biology. 2017;114:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Yashin AI. Age Patterns of Incidence of Geriatric Disease in the US Elderly Population: Medicare- Based Analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(2):323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Kulminski A, Yashin AI. Morbidity risks among older adults with pre-existing age-related diseases. Experimental gerontology. 2013;48(12):1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javitt JC, McBean AM, Sastry SS, DiPaolo F. Accuracy of coding in Medicare Part B claims: cataract as a case study. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1993;111(5):605–607. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090050039024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Yashin AI. Time trends of incidence of age-associated diseases in the US elderly population: Medicare-based analysis. Age and ageing. 2013;42(4):494–500. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Yashin A. Population-based analysis of incidence rates of cancer and noncancer chronic diseases in the US elderly using NLTCS/medicare-linked database. ISRN Geriatrics. 2013;2013 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll KJ. On the use and utility of the Weibull model in the analysis of survival data. Controlled clinical trials. 2003;24(6):682–701. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu HP, Xia X, Chuan HY, Adnan A, Liu SF, Du YK. Application of Weibull model for survival of patients with gastric cancer. BMC gastroenterology. 2011;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Statistics in medicine. 2004;23(1):51–64. doi: 10.1002/sim.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmet P, Alberti K, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414(6865):782–787. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990–2010. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(16):1514–1523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the US population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes care. 2009;32(2):287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association AD. [22 Maret 2016];Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2016. 2016 [serial online] http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/39/Supplement_1. S13 full pdf.

- 19.Yashkin AP, Picone G, Sloan F. Causes of the Change in the Rates of Mortality and Severe Complications of Diabetes Mellitus: 1992–2012. Medical care. 2015;53(3):268–275. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2015;29(8):1228–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sloan FA, Grossman DS, Lee PP. Effects of receipt of guideline-recommended care on onset of diabetic retinopathy and its progression. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(8):1515–1521. e1513. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geiss LS, Pan L, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, Benjamin SM, Engelgau MM. Changes in incidence of diabetes in US adults, 1997–2003. American journal of preventive medicine. 2006;30(5):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham TM, Pencina KM, Pencina MJ, Fox CS. Trends in diabetes incidence: the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(3):482–487. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris MI, Eastman RC. Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2000;16(4):230–236. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dmrr122>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association AD. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2017: Summary of Revisions. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Supplement 1):S4–S5. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin S, Little P, Hales C, Kinmonth A, Wareham N. Diabetes risk score: towards earlier detection of type 2 diabetes in general practice. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2000;16(3):164–171. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(200005/06)16:3<164::aid-dmrr103>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.