Abstract

Introduction

Pre-operative biopsy and diagnosis of chordomas of the mobile spine is indicated as en bloc resections improve outcomes. This review of the management of mobile spine chordomas includes two cases of unexpected mobile spine chordomas where a preoperative tissue diagnosis was decided against and may have altered surgical decision-making.

Case presentation

Two lumbar spine chordomas thought to be metastatic and primary bony lesions preoperatively were not biopsied before surgery and eventual pathology revealed chordoma. Preoperative diagnoses were questioned during surgery after an intraoperative tissue diagnosis of chordoma in one case and unclear pathology with non-characteristic tumor morphology in the other. The surgical plan was altered in these cases to maximize resection as en bloc resection reduces the risk of local recurrence in chordoma.

Discussion

Mobile spine chordomas are rare and en bloc resection is recommended, contrary to the usual approach to more common spine tumors. Since en bloc resection of spine chordomas improves disease free survival, it has been recommended that tissue diagnosis be obtained preoperatively when chordoma is considered in the differential diagnosis, in order to guide surgical planning. We present two cases where a preoperative biopsy was considered but not obtained after neuroradiology consultation and imaging review, which may have been managed differently if the diagnosis of spine chordomas were known pre-operatively.

Introduction

Chordomas are rare primary bone tumors with notochord origins that occur with an incidence of 0.08 in 100,000 and peak between the 5th and 6th decades of life. Most are located at the extremes of the craniospinal axis, with 40% at the skull base and 50% in the sacrococcygeal region [1, 2]. Despite this preferential distribution, cases in the mobile spine are well described [3]. Chordomas are characterized as low grade tumors and follow an indolent course but can grow to cause spinal canal stenosis or instability and pathological fractures [4].

Treatment protocols include radiation alone or surgery with or without radiation. Surgical approaches include an intralesional excision, en bloc resection, or en bloc resection with margins and adjuvant radiotherapy is often given. Local recurrence rates are high and chordomas are relatively radioresistant tumors, and en bloc resection is the only treatment that provides good chances of disease free survival beyond 5 years [5, 6]. Depending on the location of the tumor in the spine, en bloc resection is not always possible and the benefits need to be weighed with potential risks. Accordingly, there are established classifications to assist with planning and guiding aggressiveness of surgical resection [4, 7].

A preoperative biopsy is indicated in potential chordomas to confirm the diagnosis and surgical approach planning, which may differ from other potential diagnoses. Here we present two cases of lumbar spine chordomas in which a biopsy was not obtained due to imaging favoring of alternative diagnoses. We discuss the impact on patient care of this approach and recommend when one may consider preoperative tissue diagnosis.

Case 1

A 63-year-old previously healthy female presented with 8 months of progressive lower back pain radiating into her legs. She had limited ambulation and had begun using a walker. She had no known history of cancer but did have a family history of breast cancer in her mother. Figure 1a, b shows an L4 pathological on CT with coarse trabeculations in the vertebral body suggesting intraosseous hemangioma, initially treated conservatively. Follow up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1c) then demonstrated a mass extending posteriorly into the canal and left L4/5 foramina and she was referred for neurosurgical opinion.

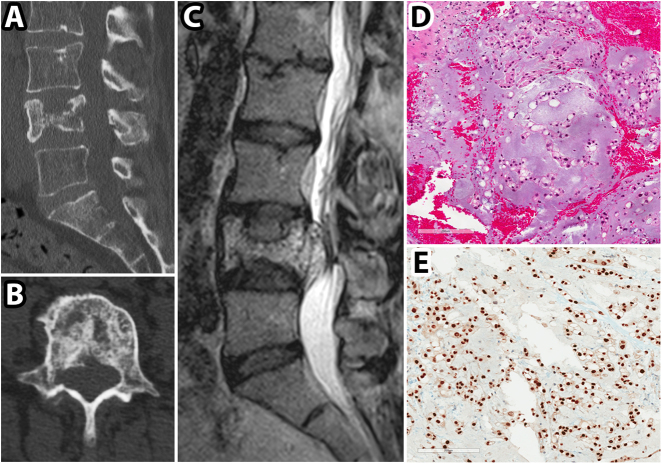

Fig. 1.

CT, MRI, and pathological images for patient in Case 1. a, b preoperative sagittal and axial CT images showing an L4 vertebral body pathological fracture; c preoperative sagittal T2 weighted MRI image demonstrating hyperintense soft tissue mass extending from L4 vertebral body to the spinal canal; d Hematoxylin and eosin stained tumor section showing tumor cells with foamy to clear cytoplasm and examples of physaliferous cells; e brachyury immunolabelled tumor section demonstrating strong labeling

An image-guided biopsy was requested. There was a consensus between two neuroradiologists that the most likely diagnosis was an osseous hemangioma with extra-osseous extension and both plasmocytoma and chordoma were considered much less likely. Given the likelihood of the presumptive diagnosis of hemangioma and the risk of hemorrhage during the procedure, CT guided biopsy was deemed unnecessary.

She underwent preoperative embolization of the lesion based on the presumed diagnosis of hemangioma, where no highly vascular tumor was seen, followed by the planned posterior decompression and fusion with tumor resection. After pedicle screw insertion (L2-3 and L5-S1) and decompression, a greyish mass was seen in the epidural space with a thin capsule which raised concern of an alternative diagnosis. The results of an intraoperative open biopsy were consistent with chordoma. The operative plan was then modified to a more radical resection. An L4 corpectomy with cage insertion was completed and all visible tumor was removed.

She did not have any major complications and was transferred to rehab postoperatively. The final pathology confirmed chordoma with physaliferous cells (Fig. 1d) and strong cellular immunolabeling with brachyury (Fig. 1e). She did undergo adjuvant radiotherapy.

Case 2

A 68-year-old female presented with a new diagnosis of an endometrial mass and two weeks of progressive lower back pain and limited ambulation, as well as mild left hip flexion weakness. A CT scan showed an L2 lytic lesion extending posteriorly on the left side with an associated pathological fracture (Fig. 2a, b). An MRI showed an L2 lesion with epidural extension causing mild canal stenosis and extension into posterior elements on the left side (Fig. 2c, d). A similar discussion regarding the potential role for biopsy took place and it was chosen against as a metastatic lesion was highly favored, and no biopsy was required.

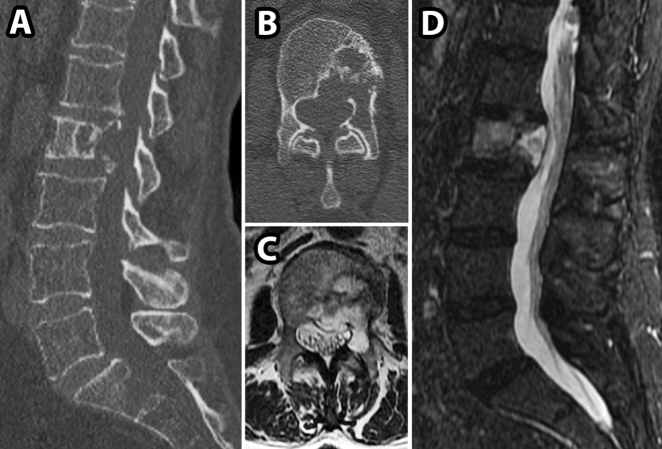

Fig. 2.

CT and MRI images for patient in Case 2. a, b, preoperative sagittal and axial CT images showing an L2 lytic lesion and associated pathological fracture; c, d preoperative sagittal and axial T2 weighted MRI images demonstrating hyperintense soft tissue mass extending from L2 vertebral body into the spinal canal

The T12-L1 and L3-4 pedicle screws were placed as planned and decompression carried on extending to the left pedicle. At this point a lesion of liquid-consistency presented itself and intraoperative pathology was described as lesional but diagnosis was not yet clear. The surgical plan was then altered to a more radical approach with partial vertebrectomy and all visible tumor was removed to attempt gross total resection as the nature of the lesion was unclear.

Her postoperative course was non-complicated and she was discharged home. Final pathology showed chordoma, confirmed with brachyury immunolabelling. She was offered a redo operation for attempted en bloc resection consistent with the literature but she instead elected to pursue radiation therapy at this time [8].

Discussion

Although it is well established that en bloc resection is the optimal treatment for chordomas, these lesions are not frequently found in the mobile spine. Since other tumors especially metastatic lesions are much more frequent, these are often favored and surgical resection is planned accordingly. There are many published cases of chordomas where other diagnoses were presumed preoperatively [9–13], and at least one case report where preoperative biopsy was not done and an intraoperative diagnosis of chordoma was made, changing the operative plan to en bloc resection [9].

The initial surgical procedure for chordoma is the sole opportunity to achieve an en bloc resection, highlighting the importance of tissue diagnosis for unusual appearing osseous lesions of the mobile spine to guide decision making. The surgical approach for an en bloc resection in the spine differs significantly from the more standard posterior fusion and antero–lateral decompression through the pedicles, used often for metastatic disease and other tumors. In the spine, en bloc resection and anterior column reconstruction might entail nerve root sacrifice and risk of neurological deficits. This may be acceptable to some patients but not all, and require thorough pre-operative discussion. Accordingly, it has been recommended that a preoperative biopsy be obtained for a lesion where a chordoma is considered in the differential diagnosis prior to planning the surgical approach [6].

In these two cases, chordoma was considered in the differential diagnosis and a preoperative biopsy was discussed but not completed prior to resection due to imaging characteristics being more suggestive of alternative diagnosis. Here we hope to underscore the importance of adherence to recommendations for management of potential mobile spine chordomas, which should be followed regardless personal and institutional biases. Diagnoses based solely on imaging are not always correct, and in cases where pre-operative diagnosis has the potential to change management significantly, it must be obtained. Patients are better served by undergoing a biopsy that turns out to be negative for chordoma followed by surgery than a suboptimal surgical resection plan based on imaging diagnosis only (“The greatest danger is not that our aim is too high and we miss it but that it is too low and we reach it – Michelangelo”).

Clearly, preoperative diagnosis is important in guiding patient counseling and in guiding surgical approach to potentially reduce the risk of local recurrence of chordomas. In future cases where CT guided biopsy is not available or even if deemed unnecessary by neuroradiology, one may consider a transpedicular needle biopsy prior to planning surgical resection according to recommendations made by Boriani et al. [7].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, Ishibe N, Parry DM. Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973-1995. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:1–11. doi: 10.1023/A:1008947301735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mindell ER. Chordoma. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1981;63:501–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163030-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gokaslan ZL, Zadnik PL, Sciubba DM, Germscheid N, Goodwin CR, Wolinsky JP, et al. Mobile spine chordoma: results of 166 patients from the AOSpine Knowledge Forum Tumor database. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;24:644–51. doi: 10.3171/2015.7.SPINE15201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;204:9–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergh P, Kindblom LG, Gunterberg B, Remotti F, Ryd W, Meis-Kindblom JM. Prognostic factors in chordoma of the sacrum and mobile spine: a study of 39 patients. Cancer. 2000;88:2122–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2122::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boriani S, Bandiera S, Biagini R, Bacchini P, Boriani L, Cappuccio M, et al. Chordoma of the mobile spine: fifty years of experience. Spine. 2006;31:493–503. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000200038.30869.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Primary bone tumors of the. Spine Terminol Surg Staging Spine. 1997;22:1036–44. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ailon T, Torabi R, Fisher CG, Rhines LD, Clarke MJ, Bettegowda C, et al. Management of locally recurrent chordoma of the mobile spine and sacrum: a systematic review. Spine. 2016;41:S193–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breen N, Eames N. Chordoma of the lumbar spine—a potential diagnosis not to be forgotten. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012:4. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2012.5.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chadha M, Agarwal A, Wadhwa N. Chondroid chordoma of the L5 spinous process and lamina: a case report. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:803–6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0906-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conzo G, Gambardella C, Pasquali D, Ciancia G, Avenia N, Pietra CD, et al. Multifocal thoracic chordoma mimicking a paraganglioma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:497–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.119312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones RB. Chordoma of the third lumbar vertebra simulating carcinoma of the prostate with vertebral metastasis. Report of a case. Br J Surg. 1960;48:162–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004820817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khong P, Milross J, Cherukuri RK. Lumbar chordoma mimicking a neurogenic tumour. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:302–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]