Highlights

-

•

The ability of indigenous fungi in degradation of crude oil was examined.

-

•

Two strains exhibited a cell surface hydrophobicity higher than 70%.

-

•

The two strains RMA1 and RMA2 reduced surface tension in MSM containing 1% crude oil.

Keywords: Biodegradation; Kinetics; Crude oil; 2, 6-dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP); Penicillium

Abstract

Among four crude oil-degrading fungi strains that were isolated from a petroleum-polluted area in the Rumaila oil field, two fungi strains showed high activity in aliphatic hydrocarbon degradation. ITS sequencing and analysis of morphological and biochemical characteristics identified these strains as Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2. Gravimetric and gas chromatography analysis of the crude oil remaining in the culture medium after 14 days of incubation at 30 °C showed that RMA1 and RMA2 degraded the crude oil by 57% and 55%, respectively. These strains reduced surface tension when cultured on crude oil (1% v/v) and exhibited a cell surface hydrophobicity of more than 70%. These results suggested that RMA1 and RMA2 performed effective crude oil-degrading activity and crude oil emulsification. In conclusion, these fungal strains can be used in bioremediation process and oil pollution reduction in aquatic ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Crude oil is a major source of income for Iraq, which is one of the largest global oil producers and exporters and nearly ranked fourth in the world in terms of oil reserves. Incidental spills of crude oil and frequent illegal disposal of oil waste lead to serious damage to environmental life. Cleaning up sites contaminated with crude oil is a priority task for the reparation of the natural environment and commonly accomplished using chemical, physical, and thermal methods. However, these methods are relatively expensive and require site restoration. Numerous physicochemical and biological methods have been assessed for treating oil-contaminated environments [1].

Biological treatment is preferred to physicochemical processes because of its feasibility, reliability, and capability to achieve high removal efficiency with low cost. Other reasons include the simplicity of its low-energy design, construction, operation, and use, and its use of biodegradation rather than the accumulation of hydrocarbons at another stage or degradation using chemical agents; biological treatment is thus a cost-effective method [2,3]. In a biological process, microorganisms can use hydrocarbon as their sole energy and carbon source and degrade instead of accumulate them at another stage [4]. Biological treatment can have an advantage over physicochemical treatment systems in the removal of spills because it provides vital biodegradation of oil parts by microorganisms, is a “green” alternative for treating hazardous contaminants due to its lack of environmentally degrading effects, and may be cheaper than other methods [5].

Various microorganisms, such as bacteria, algae, yeasts, and fungi, have the potential to degrade hydrocarbons. Indigenous microorganisms with specific metabolic capacities have played a significant role in the biodegradation of crude oil and have probably adapted to environments that require treatment [6]. Rahman et al. [7] reported that bacterial consortia isolated from crude oil-contaminated soils have the capacity to degrade crude oil fractions.

Besides bacteria, fungi are one of the best oil-degrading organisms; various studies have identified many fungal species capable of using crude oil as their sole source of carbon and energy, such as Cephalosporium, Rhizopus, Paecilomyces, Torulopsis, Pleurotus, Alternaria, Mucor, Talaromyces, Gliocladium, Fusarium, Rhodotorula, Cladosporium, Geotrichum, Aspergillus, and Penicillium [[8], [9], [10]].

EL-Hanafy et al. [11] found that the Aspergillus and Penicillium isolated from oil-contaminated sites near the Red Sea in the Yanbu region were highly efficient in crude oil degradation. The use of fungi as a means of bioremediation provides an effective option of cleansing the environment of contaminants.

The present study aimed to screen and identify oil-degrading fungal strains from crude oil in various polluted sites in the Rumaila oil field, Iraq, and examine the capability of indigenous fungi to degrade crude oil. This region was selected because it plays a significant role in the Iraqi crude oil industry.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Crude oil from the Rumaila oil field was obtained from the Southern Oil Company (Basra, Iraq). Other chemicals used were of analytical reagent grade.

2.2. Sample collection

Soil samples from the surface layer (5–10 cm) were collected from the Rumaila oil field, Basra, Iraq, and maintained in plastic containers.

2.3. Isolation and identification of fungi

Mineral salt medium (MSM) and potato dextrose broth were used for the isolation and maintenance of fungal isolates. Five grams of each collected soil sample were incubated in 250 Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL freshly prepared MSM, which consisted of NaCl (0.5 g/L), (NH4)2SO4 (0.1 g/L), NaNO3 (0.2 g/L), MgSO4·7H2O (0.025 g/L), K2HPO4·3H2O (1.0 g/L), and KH2PO4 (0.4 g/L), with 7.0 pH and supplemented with 1% crude oil, for 7 days at 30 °C and 150 r/min on a rotary shaker.

Following enrichment, parts of the medium were transferred and inoculated onto MSM plates containing 1% and 1.5% of crude oil and agar, respectively, and incubated at 30 °C for 37 days. Finally, various pure colonies were collected from the plates and stored in PDA slants. Four isolated strains were selected for further study on the basis of their capability to grow on the MSM containing 1% crude oil.

2.4. Morphology of isolated strains

Pure fungal isolates were examined under a light microscope for their morphology, namely, size, shape, spore texture, and color. The fungi were identified using morphological characters and taxonomic keys provided in the mycological keys [12].

2.5. Molecular identification of isolated strains

Total DNA isolation was conducted following a modified CTAB method [13]. For molecular identification, PCR amplifications of ITS1 and ITS4 regions were performed in a volume of 25 μL, containing 1 μL of each specific primer, namely, ITS1F (forward) (5ʹ-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3ʹ) and ITS4R (reverse) (5ʹ-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3ʹ), 12.5 μ/L 2 × Tsingke Master Mix blue (Tsingke Biological Technology Co., Ltd), and 1 μ/L template DNA. DNAse/RNase-free distilled water was used to create the 25 μL volume. The thermocycling for PCR amplifications was in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. After electrophoresis detection, the PCR products were sequenced using a 3730xl DNA sequencer (ABI, USA) by Tsingke Biological Technology, Co., Ltd. Sequences were checked in the similarity rank from FASTA Nucleotide.

Database queries were used to estimate the degree of similarity with the sequence of other genes by the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nem.nih.gov). Phylogenetic trees and sequence analyses were constructed by the neighbor-joining method using the software MEGA (Version 6.0) [14].

2.6. Crude oil degradation

Biodegradation experiments were performed in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of MSM with 1% crude oil as sole carbon source. Prior to adding crude oil, media were sterilized through autoclaving at 121 °C for 30 min. Five 5 mm plugs cut from the outer edge of an actively growing culture on a PDA plate were transferred into the MSM supplemented with crude oil. The flasks were incubated at 30 °C for 14 days. Non-inocula were used as the control. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

A modified 2,6-Dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP) method was used to estimate the degradation capability of crude oil by Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2. Five 5 mm mycelial plugs of RMA1 and RMA2 were inoculated onto degradation media with 0.4 μg/mL of DCPIP and incubated for 14 days at 30 °C. The decolorization of DCPIP (from blue to colorless) indicated a crude oil-degradation capability of the strains RMA1 and RMA2.

2.7. Degradation kinetics

The degradation of crude oil fits first-order reaction kinetics and can thus be expressed as follows:

| InCt = InC0 − Kt, | (1) |

where Ct is the residual crude oil concentration at any time; C0 represents the initial crude oil; K denotes the speed constant, which reflects the degradation rate; and t stands for time (day). The half-life period of crude oil was calculated as follows:

| t1/2 = ln2/k, | (2) |

where k is the biodegradation rate constant (day−1).

2.8. Extraction and analysis of crude oil

The remaining crude oil was extracted from each sample using chloroform with an equal volume of degradation media. Moisture was removed from the extracted crude oil using anhydrous sodium sulfate. The chloroform was evaporated in a 55 °C water bath with a rotary evaporator. Finally, the solvent was evaporated by exposure to nitrogen gas. The treated/extracted crude oil was analyzed by gravimetric analysis and gas chromatography (GC).

2.8.1. Gravimetric analysis

The gravimetric determination of the residual crude oil after biodegradation was performed by weighing the quantity of the crude oil. The estimated crude oil degradation efficiency was calculated as follows:

| D = (ρ0 − ρ1 − ρ2)/ρ0 × 100%, | (3) |

where ρ0 is the initial concentration of the crude oil, ρ1 denotes the remaining crude oil concentration at different incubation periods, and ρ2 represents the concentration of abiotic removal.

The depletion of the crude oil in the medium was determined, and the specific degradation rate was calculated as follows:

| dx/x0. dt, | (4) |

where dx is the change in concentration of the substrate, x0 represents a substrate concentration, and dt denotes a time interval.

2.8.2. Gas chromatography

GC analysis was performed on a MIDI-Sherlock GC (Agilent, USA), which was equipped with a flame ionization detector. Crude oil was separated on the 19091z-433 PH-1 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) under the following conditions. The inlet temperature program was 50 °C/min.

The initial and final temperatures of the oven were kept 35 °C (5 min) and 28 °C. The temperature program of the oven and final hold time were 10 °C/min and 15 min, respectively. Nitrogen was used as carrier gas. Detector temperature was 280 °C. Hydrogen gas and air flow rates were 40 and 400 mL/min, respectively. One microliter of sample was injected with a 1:50 split ratio, and the total run time was 58.12 min. Crude oil biodegradation was quantified using an external standard method.

2.9. Emulsification activity, fungi adherence to hydrocarbons, and liquid surface tension

An equal volume of cell-free culture broth (obtained by centrifugation at 5000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min) and crude oil was mixed by a vortex for 2 min and incubated at room temperature for 24 h. Emulsification activity percentage was calculated by dividing the height of the emulsified layer (mm) by the total length of the solution column (mm). Fungal adhesion to hydrocarbons was tested as described by Pruthi and Cameotra [15].

The surface tension of the fungi culture was measured using a Force Tensiometer-K100 (Hamburg, Germany). After 14 days of fungal culture, the surface tension was tested using the Wilhelmy plate technique and expressed in mN/m−1 units.

2.10. Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS package program Version 20 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Isolation and identification of crude oil-degrading fungi

Four fungi strains were isolated from enrichment cultivations that were performed at 30 °C for 14 days. Two of the isolated strains exhibited a higher rate of growth on crude oil than the others and were thus selected for further study. These strains (RMA1and RMA2) were initially identified using classical morphological and biochemical tests. Molecular identification of isolated fungi was performed by amplifying and sequencing the ITS region.

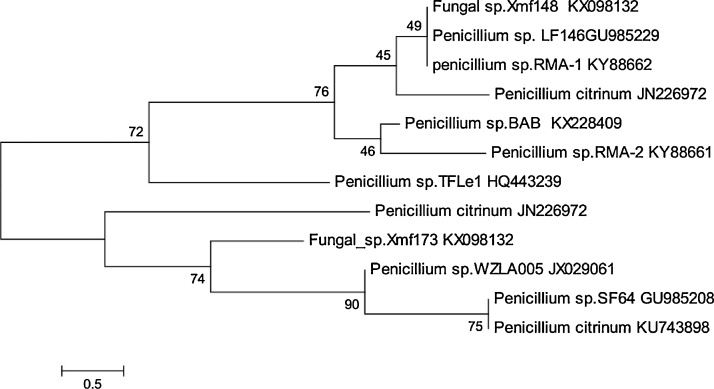

The ITS region of the filamentous fungi strains was sequenced, and sequences were submitted to GenBank with accession numbers KY883662 (RMA1) and KY88661 (RMA2). The results of the identification procedure showed that the isolated fungi were affiliated to genus Penicillium. Fig. 1 illustrates the phylogenic trees of these isolated fungi strains.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic trees of the two fungi strains.

3.2. Estimation of hydrocarbon degradation capability through 2,6-DCPIP assay

Five 5 mm plugs of Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 from the plates were aseptically extracted by a sterile cork borer and inoculated into 100 mL of MSM supplemented with 1% (v/v) crude oil and 40 μg/100 mL of redox indicator. The cultures were incubated at 30 °C and shaken at 150 rpm for 14 days. The change in the color of the inoculated degradation medium from deep blue to colorless indicated the capability of the fungi to degrade crude oil. One milliliter of RMA1 and RMA2 mycelial suspension was inoculated in a tube containing 10 mL MSM with 1% crude oil and 0.16 mg/L of DCPIP, respectively.

The tubes were incubated at 30 °C at 60 rpm. The color gradually changed from deep blue to colorless, and this reaction suggested that Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 could degrade crude oil. During the microbial oxidation process to petroleum hydrocarbons, electrons are transferred to electron acceptors, such as nitrates, sulfates, and O2. The capability of a microorganism to use hydrocarbon substrate can therefore be checked using an electron acceptor, such as DCPIP, by observing the color change of DCPIP from blue (oxidized) to colorless (reduced) [16].

The mechanism used by fungi to biodegrade crude oil can be observed by incorporating an electron acceptor, such as DCPIP [8,11]. This result indicated that the two fungi had the capability to degrade crude oil. Therefore, DCPIP assay is an effective method for screening crude oil-degrading strains [11]. DCPIP decolorization, crude oil weight loss, and fungal proliferation are considered main indicators that help identify fungal isolates that can degrade crude oil.

3.3. Emulsification activity, cell surface hydrophobicity, and surface tension

Table 1 shows the effect of crude oil on cell growth, cell surface hydrophobicity, surface tension, and emulsification activity of Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 after 14 days of incubation at 30 °C. The two strains had the same high cell surface hydrophobicity (71.5%); this characteristic might be an important property in crude oil degradation [17].

Table 1.

Effect of hydrocarbons on cell growth, cell surface hydrophobicity, emulsification activity and surface tension after 14 d of incubation at 30 °C.

| Strain | Percentage of degradation (%) | Cell surface hydrophobicity (%) | Surface tension (mN/m) | Emulsification activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMA-1 | 57 ± 1.5 | 71.5 ± 2.3 | 50 ± 3.2 | 36 ± 1.0 |

| RMA-2 | 55 ± 1.3 | 71.5 ± 2.0 | 51 ± 2.6 | 31 ± 2.4 |

The surface tension MSM without fungi was 61.7 mN/m. Data are given as means ± SD from triplicate determinations.

In addition, the two strains could significantly decrease surface tension (Table 1). This result suggested that biosurfactant production by these strains led to a decrease in surface tension, but no difference was observed between two strains belonging to the same genus [5]. A direct relationship between the crude oil biodegradation of fungi strains and a decrease in surface tension was found.

Our results were similar to those of Hassanshahian et al. [17] who isolated two crude oil-degrading yeast strains, Yarrowia lipolytica PG-20 and PG-32, from the Persian Gulf. Mnif et al. [18] studied eight Tunisian hydrocarbonoclastic oil field bacteria and found that the surface tension decreased from 68 mN/m to 35.1 mN/m, and this change suggested biosurfactant production. The production of biosurfactants by microbes is directly proportional to the amount of hydrocarbon degradation [19]. Varadavenkatesan and Murty [20] found a reduction in surface tension to 36.1 mN/m at 96 h caused by a biosurfactant yield that reached 0.64 by using MSM in the crude oil.

The emulsification activity of Penicillium sp. RMA1 was slightly higher than that of Penicillium sp. RMA2. On the basis of this activity, cell surface hydrophobicity, and surface tension, the two strains were observed and validated to be indeed capable of crude oil degradation.

3.4. Biodegradation of crude oil by two fungal strains

Numerous studies have shown that various hazardous contaminants can be degraded by fungi, including Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., Cunninghamella echinulata, Talaromyces spp., Rhodotorula spp., Gliocladium spp., Penicillium spp., Cladosporium spp., and Geotrichum spp. [21,22].

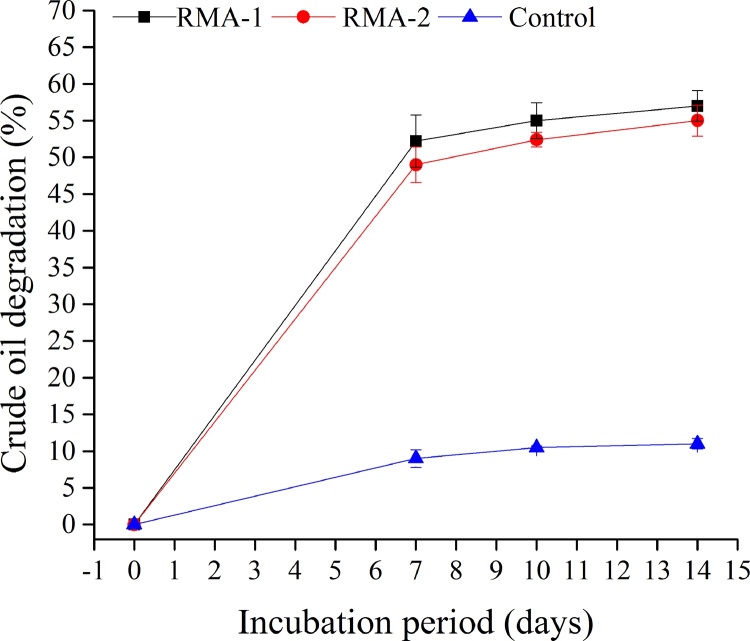

Crude oil composition was analyzed using a gravimetric method after a 7, 10 and 14 days treatment with the Penicillium strains RMA1 and RMA2 (Fig. 2). The results showed that Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 were capable of using crude oil as carbon and energy source for growth. All the fungal strains used for the degradation of crude oil in MSM were found to be potential degraders; during the 7-day incubation, RMA1 and RMA2 degraded crude oil by 52% and 49%, respectively (Fig. 2). Moreover, the degradation level continued to slightly increase during the 14-day incubation period. At the end of this incubation, RMA1 and RMA2 degraded crude oil by 57% and 55%, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Degradation of crude oil by tow fungal strains (RMA1 and RMA2).

The specific degradation rates of RMA1 and RMA2 were 0.040 and 0.039 per day, respectively. However, the degradation rate was merely 0.007 per day in the control (no fungi). When the degradation rate constant and half-life period of RMA1 and RMA2 were determined following the first-order kinetics model equation, the rate constant was higher in RMA1 (k = 0.807 per day, t1/2 = 0.858 day) than in RMA2 (k = 0.737 per day, t1/2 = 0.939 day). No significant difference in rate constant and half-life period was found between the two strains during crude oil degradation after 14 days of incubation.

EL-Hanafy et al. reported that two fungal strains affiliated to Penicillium and Aspergillus degraded crude oil at rates of 48% and 54% [23]. Aspergillus versicolor and Aspergillus niger had the fastest onset and highest extent of biodegradation of all studied fungi within 7 days of incubation [24]. The hydrocarbon degradation capabilities of Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 in the present work were close to the findings of EL-Hanafy et al. [11]. Zhang et al. [25] found that the six Aspergillus spp. isolated from oil-contaminated soil in the Ansai oilfield have high efficient in degrading crude oil. Many researchers have reported that certain fungal species are efficient metabolizers of hydrocarbons, such as Helminthosporium spp., Rhizopus spp., Fusarium spp., Aspergillus spp., and Penicillium spp. [26].

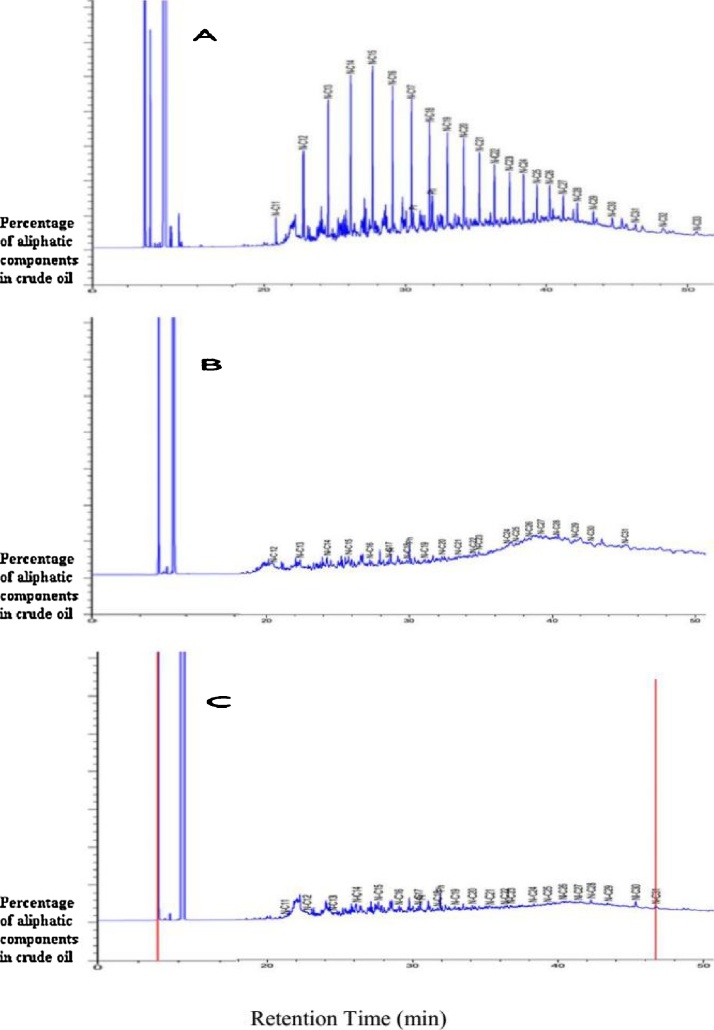

Fig. 3 shows the GC graphs of the crude oil treated by Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 in comparison with the control. Penicillium sp. RMA1 decreased the peaks of the aliphatic component in the crude oil slightly better than strain Penicillium sp. RMA2 did. No significant difference was observed between the two strains. Zhang et al. [5] reported that P. aeruginosa DQ8 isolated from oil-contaminated soils (Daqing oil field, China) could grow and degrade crude oil and diesel in aqueous solutions. However, with increased n-alkane chain length, the percentage of degradation was decreased because long n-alkane chain lengths are solid and have low solubility for degradation by fungi. The degradation of alkanes was consistent with the findings of Hassanshahian et al. [17].

Fig. 3.

Gas Chromatography tracing of residual crude oil in flasks; A: flask incubated without fungi as control B: the flask incubated with Penicillium sp. RMA1; C: the flask incubated with Penicillium sp. RMA2 for 14 days incubation at 30 °C.

The percentage degradation of the n-alkanes (C11-C25) present in the crude oil was calculated by comparing the GC of the un-degraded controls with those from each strain (Table 2). Varjani and Upasani [27] reported that P. aeruginosa NCIM showed 61.03% of biodegradation of C8-C36 hydrocarbons. Zhang et al. [28] found that C12-C21 n-alkanes in crude oil could be degraded within 8 days using Geobacillus sp. SH-1 collected from a deep oil well in Shengli oil field, China. These results suggested that the two strains had lower capability to degrade C21-C25 n-alkanes than C11-C20 n-alkanes. RMA1 and RMA2 can use aliphatic hydrocarbons, such as n-undecane, n-dodecane, n-tridecane, n-tetradecane, n-pentadecane, and n-hexadecane.

Table 2.

Percentage of n-alkane degradation in crude oil by Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 after 14 days of incubation at 30 °C, the alkane degradation rate was determined by calculating the subsurface of alkanes in a GC chromatogram against a control.

| Strain alkane | RMA1 | RMA2 | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| n-C11 | 100 | 89 | 25 |

| n-C12 | 80 | 80 | 22 |

| n-C13 | 77 | 75 | 19 |

| n-C14 | 76 | 73 | 15 |

| n-C15 | 74 | 72 | 8 |

| n-C16 | 76 | 74 | 3 |

| n-C17 | 77 | 77 | 0 |

| n-C18 | 73 | 72 | 0 |

| n-C19 | 67 | 63 | 0 |

| n-C20 | 71 | 64 | 0 |

| n-C21 | 53 | 53 | 0 |

| n-C22 | 51 | 47 | 0 |

| n-C23 | 50 | 45 | 0 |

| n-C24 | 45 | 39 | 0 |

| n-C25 | 35 | 36 | 0 |

Covino et al. [29] investigated Folsomia candida isolated from an oil-polluted soil; 79% mid- and long-chain aliphatic hydrocarbon reductions were observed. The Dietzia strain is capable of metabolizing a wide range of n-alkanes (C6-C40) [30]. Moreover, the possible different hydrocarbon metabolic pathways in the various microbial strains were indicated. Therefore, enhancing microbial recovery to degrade a wide range of hydrocarbons and crude oil is crucially significant for the bioremediation of oil pollution.

4. Conclusions

In this study, two crude oil-degrading strains Penicillium sp. RMA1 and RMA2 were isolated from the Rumaila oil field. These strains exhibited high levels of crude oil degradation, which can possibly be used for bioremediation. A direct relationship was found between the cell hydrophobicity of fungal strains and their capabilities for emulsification, crude oil biodegradation, and surface tension reduction.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Southern Oil Company (Basra, Iraq) for offering samples, and Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for GC analysis.

Contributor Information

Xiaoyu Zhang, Email: zhangxiaoyu@hust.edu.cn.

Fuying Ma, Email: mafuying@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ezeji U., Anyadoh S.O., Ibekwe V.I. Clean up of crude oil-contaminated soil. Terr. Aquat. Environ. Toxicol. 2007;1(2):54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu G.-h., Ye Z., Tong K., Zhang Y.-h. Biotreatment of heavy oil wastewater by combined upflow anaer sludge blanket and immobilized biological aerated filter in a pilot-scale test. Biochem. Eng. J. 2013;72:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moussavi G., Ghorbanian M. The biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in an upflow sludge-blanket/fixed- film hybrid bioreactor under nitrate-reducing conditions: performance evaluation and microbial identification. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;280:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang M., Liu G.-h., Song K., Wang Z., Zhao Q., Li S., Ye Z. Biological treatment of 2, 4, 6- trinitrotoluene (TNT) red water by immobilized anaerobic?aerobic microbial filters. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;259:876–884. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z., Hou Z., Yang C., Ma C., Tao F., Xu P. Degradation of n-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in petroleum by a newly isolated Pseudomonas aeruginosa DQ8. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102(5):4111–4116. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman K., Rahman T.J., Kourkoutas Y., Petsas I., Marchant R., Banat I. Enhanced bioremediation of n-alkane in petroleum sludge using bacterial consortium amended with rhamnolipid and micronutrients. Bioresour. Technol. 2003;90(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(03)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman K., Thahira-Rahman J., Lakshmanaperumalsamy P., Banat I. Towards efficient crude oil degradation by a mixed bacterial consortium. Bioresour. Technol. 2002;85(3):257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(02)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Nasrawi H. Biodegradation of crude oil by fungi isolated from Gulf of Mexico. J. Bioremed. Biodegrad. 2012;3(04) [Google Scholar]

- 9.AI-Jawhari I.F.H. Ability of some soil fungi in biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbon. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;2(2):46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawoodi V., Madani M., Tahmourespour A., Golshani Z. The Study of Heterotrophic and Crude Oil-utilizing soil fungi in crude oil contaminated regions. J. Bioremediat. Biodegrad. 2015;6(2):1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.EL-Hanafy A.A.-E.-M., Anwar Y., Sabir J.S., Mohamed S.A., Al-Garni S.M., Zinadah O.A.A., Ahmed M.M. Characterization of native fungi responsible for degrading crude oil from the coastal area of Yanbu, Saudi Arabia, B iotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017;31(1):105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe T. CRC press; 2010. Pictorial Atlas of Soil and Seed Fungi: Morphologies of Cultured Fungi and Key to Species. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle J.J. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pruthi V., Cameotra S.S. Rapid identification of biosurfactant-producing bacterial strains using a cell surface hydrophobicity technique. Biotechnol. Tech. 1997;11(9):671–674. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson K., Desai J.D., Desai A.J. A rapid and simple screening technique for potential crude oil degrading microorganisms. Biotechnol. Tech. 1993;7(10):745–748. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassanshahian M., Tebyanian H., Cappello S. Isolation and characterization of two crude oil-degrading yeast strains, Yarrowia lipolytica PG-20 and PG-32, from the Persian Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012;64(7):1386–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mnif S., Chamkha M., Labat M., Sayadi S. Simultaneous hydrocarbon biodegradation and biosurfactant production by oilfield-selected bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;111(3):525–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahbari-Sisakht M., Pouranfard A., Darvishi P., Ismail A.F. Biosurfactant production for enhancing the treatment of produced water and bioremediation of oily sludge under the conditions of Gachsaran oil field. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017;92(5):1053–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varadavenkatesan T., Murty V.R. Production of a lipopeptide biosurfactant by a novel Bacillus sp. and its applicability to enhanced oil recovery. ISRN Microbiol. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2013/621519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlas R.M. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons: an environmental perspective. Microbiol. Rev. 1981;45(1):180. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.1.180-209.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulibaly L., Gourene G., Agathos N.S. Utilization of fungi for biotreatment of raw wastewaters. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2003;2(12):620–630. [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Hanafy A.A., Anwar Y., Mohamed S.A., Al-Garni S.M.S., Sabir J.S., Zinadah O.A.A., Ahmed M.M. Isolation and molecular identification of two fungal strains capable of degrading hydrocarbon contaminants on Saudi Arabian environment. Int. J. Biol. Biomol. Agric. Food Biotechnol. Eng. 2015;9(12):1142–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 24.George-Okafor U., Tasie F., Muotoe-Okafor F. Hydrocarbon degradation potentials of indigenous fungal isolates from petroleum contaminated soils. J. Phys. Nat. Sci. 2009;3(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J.H., Xue Q.H., Gao H., Ma X., Wang P. Degradation of crude oil by fungal enzyme preparations from Aspergillus spp. for potential use in enhanced oil recovery. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016;91(4):865–875. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obire O., Anyanwu E. Impact of various concentrations of crude oil on fungal populations of soil. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;6(2):211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varjani S.J., Upasani V.N. Biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons by oleophilic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5514. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;222:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J., Zhang X., Liu J., Li R., Shen B. Isolation of a thermophilic bacterium Geobacillus sp. SH-1, capable of degrading aliphatic hydrocarbons and naphthalene simultaneously, and identification of its naphthalene degrading pathway. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;124:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Covino S., D'Annibale A., Stazi S.R., Cajthaml T., Čvančarová M., Stella T., Petruccioli M. Assessment of degradation potential of aliphatic hydrocarbons by autochthonous filamentous fungi from a historically polluted clay soil. Sci. Total. Environ. 2015;505:545–554. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X.-B., Chi C.-Q., Nie Y., Tang Y.-Q., Tan Y., Wu G., Wu X.-L. Degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons (C6-C40) and crude oil by a novel Dietzia strain. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102(17):7755–7761. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]