1. Introduction

Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is an extremely uncommon condition that is often life threatening. It requires aggressive medical and often surgical management. EPN is a gas-producing, necrotizing infection involving the renal parenchyma. EPN is usually caused by an Escherichia coli (70%) or Klebsiella pneumonia (24%) infection.1, 2, 3 Although bilateral EPN is a rare phenomenon that occurs in approximately 10% of EPN cases, the mortality rate of bilateral EPN is approximately 50%.4

The pathogenesis of EPN is not well understood. What is known is that EPN occurs more commonly in people with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Published case series show that poorly controlled diabetes was present in more than 80% of patients with EPN.1,3 It is thought that the increased tissue glucose level in diabetic patients provides a favourable microenvironment for gas forming microbes. Research also shows preponderance in females, outnumbering men 6:1. This has been attributed to the higher rate of UTIs in women.3

Urinary infections which result in pyelonephritis becoming emphysematous is proposed to be due to a combination of gas-forming bacteria, enhanced proliferation of microorganisms, vascular impairment with ischemia or infarct, and high tissue glucose concentration.2,5 Gas formation can be rapid, and the continued presence of gas indicates active infection and ineffective antimicrobial therapy.1

EPN is a life threatening condition; it has been shown that the mortality rate associated with the disease has improved dramatically with advances in antibiotics, medical management of diabetes, resuscitation and minimally invasive treatments. The mainstay of management of EPN is fluid resuscitation, glycemic control and broad-spectrum antibiotic cover. The traditional surgical teaching remains that treatment should be aggressive, with nephrectomy considered the treatment of choice.2,5 There is however a change in this dogma due to the significant advances in percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD).5 Some treatment regimes recommend PCD should be performed on patients who have localized areas of EPN with functioning renal tissue. This means that the patient may retain renal function, hence preventing dialysis. Over the last decade there has been a gradual shift towards this approach, with or without nephrectomy at a later stage.5

Huang and Tseng reported significant treatment success rates with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics (66%) and with nephrectomy (90%).2 This shows that the traditional treatment of nephrectomy is still the gold standard, with decreased mortality rates, however it does compromise renal function. A nephron-sparing approach in bilateral disease can prevent the need for life-long dialysis. It is however a fraught decision as usually these patients are critically unwell and first require management of sepsis.

We present the clinical course of a man who presented with bilateral EPN and was successfully managed by medical therapy.

2. Case report

A 54-year-old male in septic shock was transferred to our tertiary hospital from a rural hospital after presenting with malaise, rigors and right upper quadrant and flank pain for 7 days. The man was initially treated with antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole) for what was thought to be acute cholecystitis, which progressed to ascending cholangitis.

On transfer to our tertiary hospital the man was in multi-organ failure. He had oxygen saturations of 80% on 6L of oxygen via a Hudson Mask. He was haemodynamic compromised with a systolic blood pressure of 80 and a sinus tachycardia up to 120 beats per minute. On systematic examination he was noted to have bilateral renal angle tenderness. In the emergency department he was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit.

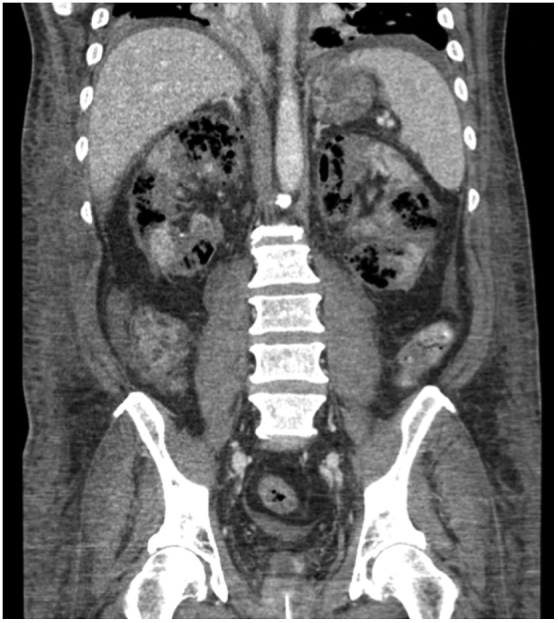

The man quickly developed severe metabolic acidosis and was noted to have anuric renal failure as well as thrombocytopenia. He was placed on dialysis, his antibiotics where broadened to meropenum, metronidazole and fluconazole. He was stabilised and underwent a CT scan. This CT scan showed that he had bilateral EPN (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). His only significant past medical history was type two diabetes. Once the diagnosis of bilateral EPN was made, he was referred to the urology service. A long discussion was held with the patient's next of kin to consider whether bilateral nephrectomies were appropriate. The ultimate decision was not to perform this procedure due to his dire clinical situation and expressed wishes.

Fig. 1.

Initial axial CT scan of patient.

Fig. 2.

Initial coronal CT scan of patient.

Clinically, the man deteriorated; he was extremely coagulopathic with an INR of 16. H is metabolic acidosis progressed and he developed liver failure with worsening synthetic failure and required maximal inotropic support.

A case conference was held between the man's next of kin, ICU and the urology team. It was decided that it was in the patients best interests to treat him medically. This decision was based on the patient previously discussing with his next of kin that he would not like life-long dialysis, as he did not like hospitals. His high operative risk was also a reason due to the high operative risk of mortality due to his coagulopathy, sepsis and multi-organ failure.

The man was managed in ICU with supportive care and antibiotics. The antibiotics were rationalised to ceftriaxone once the sensitivities to the Klebsiella where known. He underwent a CT scan on day 3 of his admission, which showed no drainable collections. He was extubated on day 6 of his admission and required ongoing dialysis for his acute kidney injury. He received 4 weeks of IV ceftriaxone, which was, transitioned to oral augmentin duo forte for a further 8 weeks.

The repeat CT after 4 weeks (Fig. 3) of treatment of IV ceftriaxone showed that within the limits of a non-contrast study, there has been no significant change in the appearance of the kidneys since the initial CT. Prior to transfer back to his referring hospital he remained afebrile, was hemodynamically stable but remained on intermittent hemodialysis. His creatinine remained 250 and he requires regular hemodialysis.

Fig. 3.

4 weeks follow up axial CT scan.

3. Discussion

Bilateral EPN is a rare phenomenon and presently there is no consensus its management. Bilateral EPN is associated with a high patient mortality but can, in the right circumstances be managed with nephron-sparing treatments. This case to our knowledge is only the 17th case in the literature describing EPN being managed with medical treatment alone. Unfortunately in this case, even with nephron-sparing techniques the patient still requires life long dialysis.

Disclosures

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

No additional scholarships, grants, equipment or pharmaceutical items were required for this report.

Contributorship

Samuel Davies and Joanna Dargan both performed an extensive literature search and reviewed the case file. Paul Sved was involved in gaining ethical approval and deciding on the treatment of the patient. Samuel Davies wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2018.01.018.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Chen M., Huang C., Chou Y., Huang C., Chiang C., Liu G. Percutaneous drainage in the treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis: 10-year experience. J Urol. 1997;157(5):1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang J., Tseng C. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):797–805. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuchay M., Laway B., Bhat M., Mir S. Medical therapy alone can be sufficient for bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis: report of a new case and review of previous experiences. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(1):223–227. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zabbo A., Montie J., Popowniak K., Weinstein A. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis. Urology. 1985;25:293–296. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ubee S., McGlynn L., Fordham M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. Br J Urol Int. 2011;107(9):1474–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.