INTRODUCTION

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a rare chronic pain disorder, characterised by paroxysms of severe, lancinating pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Most commonly, the second and third branches of the trigeminal nerve are affected. Paroxysms of pain may be related to tactile stimuli such as hair combing, shaving or a cold wind against the patients face. The pain associated with TN is so severe that reports of patients committing suicide have been published in the literature. 1

The estimated annual incidence of TN is 27 per 100,000 person years, with peak incidence between the ages of 50 and 60.2 The vast majority of TN cases are due to microvascular compression of the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve by vascular structures. 3 TN is seen with increased frequency in patients suffering from Multiple Sclerosis (MS), where it has an estimated prevalence of 1%-6.3%, and in MS patients the condition may be bilateral. 4,5 TN may also occur secondary to space occupying lesions at the cerebello-pontine angle such as epidermoid cysts, meningiomas or vestibular schwannoma. 6

The diagnosis of TN is a clinical one, based on history and examination, with criteria for diagnosis recently published by the International Headache Society. 7 However, 3D volumetric MRI studies may be used to investigate for microvascular compression of the nerve, and for rarer, secondary causes of TN. 8 The first line treatment of TN involves medical management with carbamazepine or other anti-epileptic drugs, which have been demonstrated to be effective for pain reduction in patients with TN. 9 Although medical management has been demonstrated to be effective, 75% of TN patients ultimately undergo a surgical procedure for the relief of their pain. 10 The most commonly performed surgical procedure is microvascular decompression, where the vascular loop overlying the trigeminal nerve is displaced away from the root entry zone. Other surgical options for the treatment of TN include balloon compression of the nerve root, radiofrequency thermocoagulation, glycerol rhizolysis and stereotactic radiosurgery. 11

The aim of this paper is to report the outcomes of patients treated with microvascular decompression in a small volume regional neuroscience unit at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast between October 2011 and November 2014, and to compare these outcomes with those published in the literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed electronic records and operation notes of patients who underwent MVD by the senior author for TN between October 2011 and November 2014.

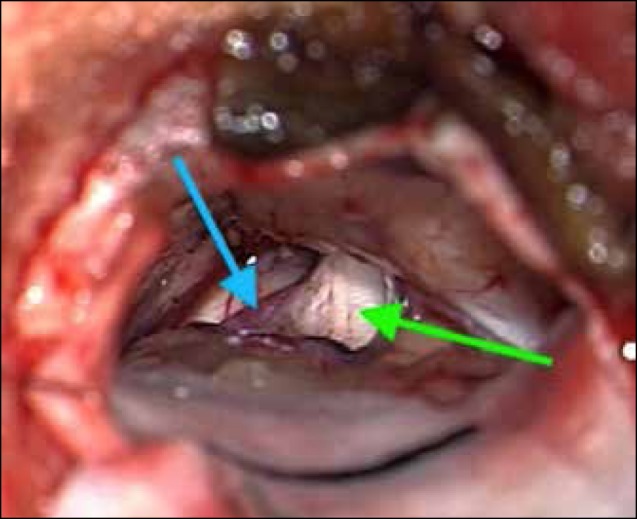

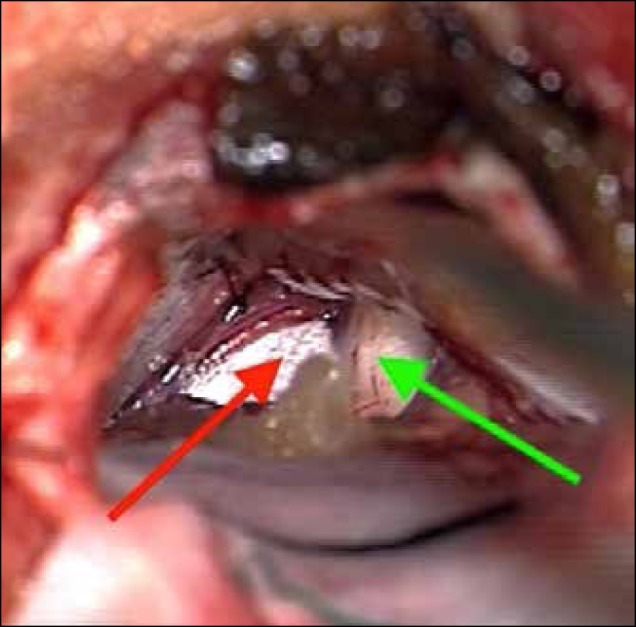

The procedure itself was performed under a general anaesthetic, with the trigeminal nerve ganglion accessed by means of a craniectomy over the asterion (located at the posterior aspect of the parietomastoid suture). Following this, the dura mater was opened to allow access to the cerebellopontine angle. The cerebellum was retracted, and the trigeminal nerve was identified with the use of a neurosurgical microscope. Following identification of the nerve, it was carefully inspected and any offending vessels are dissected off its surface: the superior cerebellar artery is most commonly implicated (Fig. 1), although compression by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, as well as the superior petrosal veins have also been reported. 12 Following dissection of the vascular structures from the trigeminal nerve ganglion, Teflon® felt is interposed between the vessel and the nerve, to maintain separation. (Fig. 2). 13 In all but four cases in this series, intra-operative auditory evoked potentials were monitored, to aid in the prevention of post-operative hearing loss.

Fig 1.

Superior cerebellar artery (blue arrow) in contact with trigeminal nerve ganglion (green arrow)

Fig 2.

Interposition of shredded Teflon® (red arrow) between superior cerebellar artery and trigeminal nerve ganglion (green arrow)

Follow up clinic reviews were used for assessment of outcome measures in this study. A Barrow Neurological Institute pain score was calculated pre and post-operatively for all patients.

RESULTS

During a 37-month period, 32 patients underwent MVD for TN. All patients were operated on by the senior author. The patients included 21 females and 11 males, with a mean age of 54 years (range 29-72). The mean time from diagnosis to surgery was 6 years (range 0.18-16 years). The mean time from first neurosurgical clinic review and operation was 308 days (range 51-663 days).

28 of the patients had medical therapy alone prior to microvascular decompression; 3 patients had previous radiofrequency treatment and 1 had previous percutaneous balloon compression.

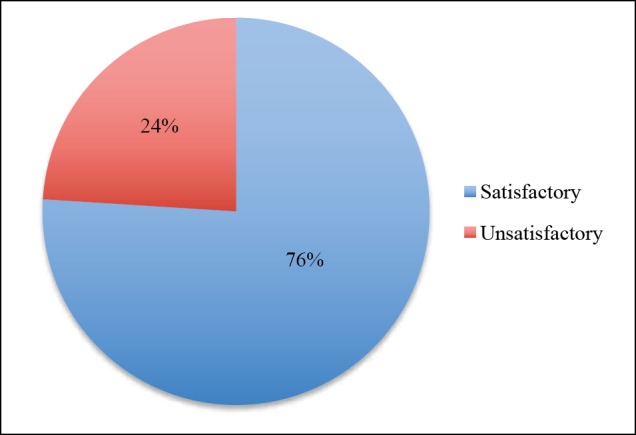

All but one of the patients had a vascular loop identified on pre-operative MRI. There was an average follow up of 254 days. A Barrow Neurological Institute pain score was calculated for all patients. Pre-operatively six (19%) patients had a score of 5, twenty-six (81%) had a score of 4. Post-operatively, at last clinic follow up, eight (24%) had a score of 4, five (16%) had a score of 3 and nineteen (60%) had a score of 1. A post-operative Barrow score of ≤3 was considered a satisfactory outcome.

Unfortunately, one patient reported the onset of contralateral pain following the procedure. In terms of other post operative complications (Table 1), 2 patients developed post operative hearing loss, 4 patients developed a cerebrospinal fluid leak, 3 patients developed minor wound infections treated with short courses of antibiotics and 1 patient developed a patch infection, requiring long-term antibiotic therapy (none of the patients required wound exploration to treat their infection). Also, 1 patient developed a minor cerebellar haematoma requiring readmission four weeks following their microvascular decompression.

Table 1.

Barrow Neurological Institute Pain Score

| Score | Pain Description |

|---|---|

| I | Pain free, no medication |

| II | Occasional pain, no medication required |

| III | Some pain, adequately controlled by medication |

| IV | Some pain, not adequately controlled by medication |

| V | Severe pain or no pain relief |

DISCUSSION

Microvascular decompression is a surgical procedure, undertaken following failure of medical therapy, or when medical therapy has intolerable adverse affects, for TN. All of our patients have an MRI pre-operatively, to assess for the presence of a vascular loop abutting the trigeminal nerve ganglion: the identification of a vascular loop compressing the trigeminal nerve has been shown to be associated with an improved outcome following MVD. 14

In addition to the open approach, fully endoscopic microvascular decompression has also been described-allowing a less invasive approach to this procedure, without an increased risk of complications according to some published evidence. 15

Due to the proximity to cranial nerve VIII, post-operative hearing loss is a possibility, with a reported incidence in the literature of 1.1-1.3%. 13,16 Brain-stem auditory evoked responses can be monitored intra-operatively in an effort to prevent hearing loss. 17 As described above, all of our patients underwent intraoperative auditory evoked potentials. However, both of the patients who experienced deafness post-operatively had normal auditory evoked potentials up until skin closure. Other potential complications include facial palsy, facial sensory loss, postoperative haemorrhage, CSF leak and meningitis. 13

In this study, at an average of 254 days post-operatively, 24 patients (76%) had a satisfactory outcome (Barrow score ≤3), while 8 (24%) reported an unsatisfactory outcome (Figure 3). A 2010 study of 372 patients treated with microvascular decompression between 1982 and 2005 for TN refractive to medical therapy reported that 84% of patients were pain-free, without the need for medication, at one year, and that 71% were pain-free without the need for medication at 10 years post-operatively. 14

Fig 3.

Trigeminal Nerve Decompression: Microvascular Surgical Outcomes.

A further study followed up 1185 patients treated with microvascular decompression in a major North American neurosurgical centre over a 19-year period, and found results more comparable to the results we are reporting. At one year, 75% of patients reported a complete response to surgery, with a further 9% reporting a partial response. Ten years post-operatively, 64% of patients reported complete relief, and 4% reported partial relief. 16

In terms of post-operative complications (Table 2), those most commonly encountered in this cohort of patients were; CSF leak (4 patients, 12%) wound infection (4 patients, 12%), hearing loss (2 patients, 6%). There was one minor post-operative cerebellar haematoma that did not require neurosurgical intervention. No patients developed a facial palsy following their operation.

Table 2.

Post-Operative Complications

| Complication | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Death | 0 |

| Facial Palsy | 0 |

| Hearing Loss | 2 (6%) |

| CSF Leak | 4 (12%) |

| Minor Wound Infection | 3 (9%) |

| Patch Infection | 1 (3%) |

| Haematoma | 1 (3%) |

| Contralateral Pain | 1 (3%) |

The limitations of this study are the small sample size, the retrospective nature of the study and the relatively short follow-up period. The reason for the disparity between the results of our centre and those reported in the literature may be: the method used to evaluate our outcomes; patients with a long duration of pre-operative symptoms may be skewing the data- the average time from diagnosis to surgery in our cohort of patients was 6 years, with one patient suffering from TN for 16 years before undergoing microvascular decompression-there is clear evidence from a number of longitudinal studies that long duration of TN prior to surgery is a negative prognostic factor. 16, 18-19

Although we consider MVD to be gold standard treatment option in patients with TN refractory to medical management or who have not responded to MVD, alternative, less invasive procedures are available, and can be considered in the elderly patient with significant co-morbidities or in patients with MS, who often have poor results following MVD. 20 Balloon micro-compression is a procedure undertaken percutaneously, under fluoroscopic guidance, aiming to crush the nerve against the skull base, as it passes through the foramen ovale. The main disadvantage of this procedure is that it often leads to facial numbness that some patients may not be prepared to accept. Long term outcomes are not as favourable as those with MVD: a large retrospective analysis of 901 patients treated with balloon micro-compression described pain relief with no need for medication in 67% of patients at one year and 48% of patients at sixteen years post procedure. 21

A further treatment modality utilised when MVD is not considered suitable is the use of stereotactic radiosurgery, delivering targeted radiation to the trigeminal nerve root entry zone. It is less effective than MVD, with rates of pain relief, without the use of medication, at ten years reported in a recently published series to be 51.5%. 22 There is also a delay in the onset of pain relief following the procedure, compared with MVD and balloon compression, that should lead to relief of pain immediately after the procedure.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it is clear that microvascular decompression is an effective treatment for TN refractory to medical management. However, the rates of post-operative pain reduction in patients undergoing this operation in our centre are not as high as those reported in the literature from two-long term outcome studies involving high numbers of patients. This may be due to a higher proportion of patients with negative prognostic factors pre-operatively (e.g., long duration of TN prior to operation), or due to discrepancy in outcome measurement. Neurologists and other physicians involved in the management of TN should consider prompt referral to a neurosurgical unit following the failure of medical therapy.

Footnotes

Provenance: externally peer- reviewed

UMJ is an open access publication of the Ulster Medical Society (http://www.ums.ac.uk).

REFERENCES

- 1.Zakrzewska JM. Insights: facts and stories behind trigeminal neuralgia. Gainesville, Florida: Trigeminal Neuralgia Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall GC, Carroll D, Parry D, McQuay HJ. Epidemiology and treatment of neuropathic pain: the UK primary care perspective. Pain. 2006;122(1-2):156-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakrzewska JM, Coakham HB. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: update. Curr Opin Neurol 2012;25(3):296-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Putzki N, Pfriem A, Limmroth V, Yaldizli O, Tettenborn B, Diener HC, et al. Prevalence of migraine, tension-type headache and trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(2):262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87(1):117-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng TM, Cascino TL, Onofrio BM. Comprehensive study of diagnosis and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia secondary to tumors. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2298-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version): Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng Q, Zhou Q, Liu Z, Li C, Ni S, Xue F. Preoperative detection of the neurovascular relationship in trigeminal neuralgia using three-dimensional fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (FIESTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(1):107-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Carbamazepine for acute and chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD005451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broggi G, Ferroli P, Franzini A. Treatment strategy for trigeminal neuralgia: a thirty years experience. Neurol Sci. 29 Suppl 1: S79–S82; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ. 2014;348:g474. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas KL, Vilensky JA. The anatomy of vascular compression in trigeminal neuralgia. Clin Anat. 2014;27(1):89-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg MS, editor. Handbook of neurosurgery. 7th ed. Stuttgart: Thieme Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarsam Z, Garcia-Fiñana M, Nurmikko TJ, Varma TR, Eldridge P. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Neurosurg. 2010;24(1):18-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohman LE, Pierce J, Stephen JH, Sandhu S, Lee JY. Fully endoscopic microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: technique review and early outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(4):E18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, Larkins MV, Jho HD. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(17):1077-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramnarayan R, Mackenzie I. Brain-stem auditory evoked responses during microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: predicting post-operative hearing loss. Neurol India. 2006;54(3):250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li ST, Pan Q, Liu N, Shen F, Liu Z, Guan Y. Trigeminal neuralgia: what are the important factors for good operative outcomes with microvascular decompression. Surg Neurol. 200;62(5):400-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theodosopoulos PV, Marco E, Applebury C, Lamborn KR, Wilson CB. Predictive model for pain recurrence after posterior fossa surgery for trigeminal neuralgia. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(8):1297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broggi G, Ferroli P, Franzini A, Nazzi V, Farina L, La Mantia L, et al. Operative findings and outcomes of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in 35 patients affected by multiple sclerosis. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(4):830-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdennebi B, Guenane L. Technical considerations and outcome assessment in retrogasserian balloon compression for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Series of 901 patients. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Régis J, Tuleasca C, Resseguier N, Carron R, Donnet A, Yomo S, et al. The very long-term outcome of radiosurgery for classical trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2016;94(1):24-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]