Abstract

AIM

To investigate 30-year treatment outcomes associated with Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) at a tertiary hospital in China.

METHODS

A total of 256 patients diagnosed with primary BCS at our tertiary hospital between November 1983 and September 2013 were followed and retrospectively studied. Cumulative survival rates and cumulative mortality rates of major causes were calculated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the independent predictors of survival were identified using a Cox regression model.

RESULTS

Thirty-four patients were untreated; however, 222 patients were treated by medicine, surgery, or interventional radiology. Forty-four patients were lost to follow-up; however, 212 patients were followed, 67 of whom died. The symptom remission rates of treated and untreated patients were 81.1% (107/132) and 46.2% (6/13), respectively (P = 0.009). The cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year survival rates of the treated patients were 93.5%, 81.6%, 75.2%, 64.7%, and 58.2%, respectively; however, the 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year survival rates of the untreated patients were 70.8%, 70.8%, 53.1%, 0%, and unavailable, respectively (P = 0.007). Independent predictors of survival for treated patients were gastroesophageal variceal bleeding (HR = 3.043, 95%CI: 1.363-6.791, P = 0.007) and restenosis (HR = 4.610, 95%CI: 1.916-11.091, P = 0.001). The cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma were 0%, 2.6%, 3.5%, 8%, and 17.4%, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Long-term survival is satisfactory for treated Chinese patients with BCS. Hepatocellular carcinoma is a chronic complication and should be monitored with long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Budd-Chiari syndrome, Chinese, Survival, Interventional radiology

Core tip: This is the first study to evaluate interventional treatment outcomes of Chinese Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) patients with more than 20-year follow-up, and the cumulative 20-year survival rate was 69.5% for patients treated by interventional radiological procedures. The cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, and 20-year survival rates for untreated BCS patients were 70.8%, 70.8%, 53.1%, and 0%, respectively. Restenosis and gastroesophageal variceal bleeding were critical factors for predicting long-term survival. Long-term follow-up to monitor the chronic complications of BCS should not be less than 10 years, and deaths greatly increase after 10-year follow-up, especially those of patients who died from hepatocellular carcinoma.

INTRODUCTION

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare disease defined as hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction at any level from small hepatic veins (HVs) to the junction of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and right atrium in the absence of right heart failure or constrictive pericarditis[1]. An obstruction that originates from endoluminal lesions (i.e., thrombosis, webs, and endophlebitis) is considered primary BCS[2]. Western and Asian patients exhibit different characteristics regarding the nature and level of obstructive lesions; therefore, clinical presentations and treatment strategies are also different in these groups[3]. In Western countries, where hepatic thrombosis is the major obstructive lesion of BCS, a step-wise therapeutic strategy aimed at minimizing invasiveness has been advocated and proven to be effective[4,5]. The most widely used treatment modalities are anticoagulation and trans-jugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS)[5,6]. However, for Asian patients, especially Chinese patients, the predominant obstructive lesions are membranous and segmental obstructions of the supra-hepatic or retro-hepatic portion of the IVC, and the most used treatment modalities are interventional re-canalization and surgery[7-11].

Till the year 2014, more than 20000 cases of BCS have been published in China[12], since the first Chinese case was reported in 1957[13]. According to a recent literature survey study, interventional radiological procedures (mainly percutaneous re-canalization) have become the most common treatment option[14], and their outcomes are good or excellent[10,15,16]. However, outcomes from more than 10-year follow-up are scarcely reported[10,15-20]. Ten years may not be long enough for long-term outcome observations in Chinese patients with BCS characterized by insidious onset and chronic development[21,22]. The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyze the 30-year follow-up outcomes of BCS patients at our center and to evaluate their long-term survival and its related predictors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

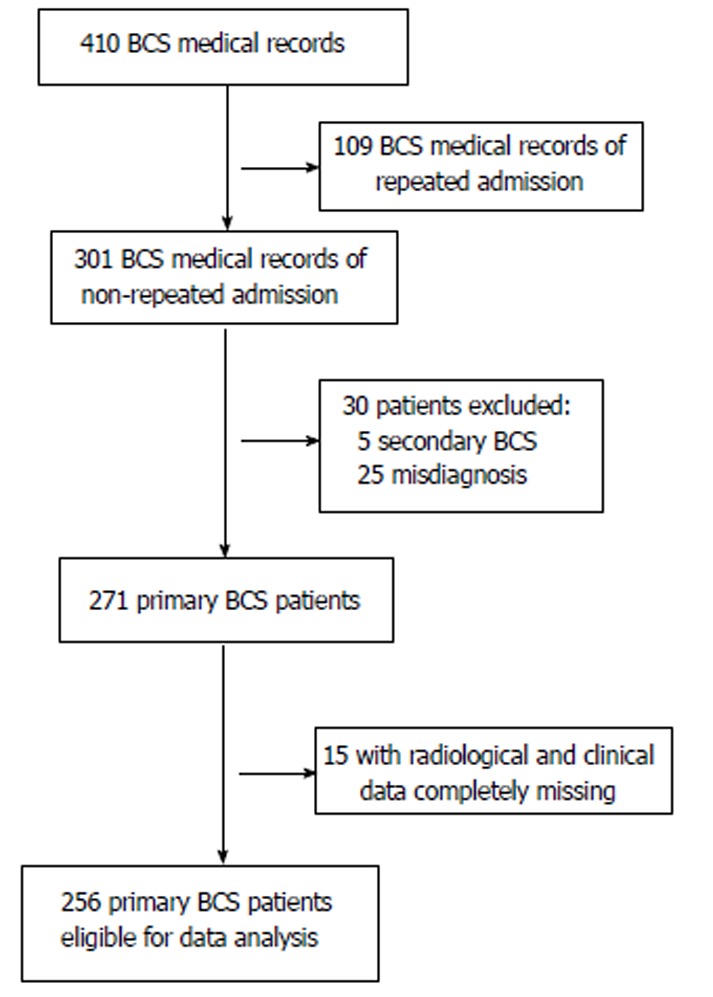

Study design and case selection

This retrospective case series study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital. All patients were informed about the benefits and related risks before treatment, and they provided written informed consent. Medical records of 410 patients treated between November 1983 and September 2013 with an admission diagnosis of BCS were identified in our hospitalization register system. There were 172 records from 63 patients that represented repeated hospitalizations; only the primary hospitalization medical records were enrolled. Thirty records were excluded, including 5 for secondary BCS and 25 for misdiagnoses of BCS. For the remaining 271 primary BCS records, 15 were not qualified for statistical analysis due to missing laboratory and imaging investigation data. Finally, 256 patients were eligible for our study. A flow chart of case selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of case selection. BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome.

Diagnosis and classification

BCS was diagnosed by color Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and/or venography of HVs and the IVC. BCS patients were classified into three groups according to the obstruction site of the hepatic venous outflow tract: (1) IVC type, manifesting as obstruction of the IVC with at least one patent HV; (2) HV type, manifesting as obstruction of the three main HVs; and (3) combined type, manifesting as obstruction of both the IVC and three main HVs[10]. Patients were considered symptomatic when they had any one of the following manifestations: abdominal pain, abdominal distention, ascites, esophageal and gastric varicose bleeding, encephalopathy, or lower-extremity edema.

Treatment

In this case series, 34 patients were untreated (did not receive any regular treatments) due to technical contraindications (n = 9), poverty (n = 10), or relatively mild symptoms (n = 15), and 222 patients received treatment. Treatment modalities used for BCS patients included medical treatments, surgical operations, and interventional radiological procedures. Medical treatments included anticoagulation, diuretics, paracentesis and reinfusion of ascites, and albumin infusion. Surgical operations included cavoatrial shunting, radical resection, meso-cavo-atrial shunting, splenopneumopexy, and splenocaval shunting and were performed as described in a previous study[23]. Interventional radiological procedures included percutaneous intravascular catheter-directed thrombolysis, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) with or without stent implantation, and TIPS, and the techniques were described in our previous studies[10,24]. Technical success of the interventional radiological procedures (mostly percutaneous recanalization) was defined as the recanalization of hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction as demonstrated by venography[10].

Data collection and follow-up

Baseline data were extracted from the medical records before treatment, including demographic data, clinical presentations, laboratory test results, and imaging data. Patients were followed until death, the end of this study (December 31, 2014), or the last outpatient visit date if the patient was lost to follow-up. Symptom remission was defined as complete remission or substantial partial remission of the main symptoms that the patients complained about most urgently. Patients were examined by color Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging at their local hospitals for restenosis evaluation, and the results were confirmed by venography at our hospital. Follow-up data were obtained from medical records or by telephone interview of the patients themselves or their family members.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers (or frequencies, if indicated) and were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are summarized as medians and ranges and were compared by using the independent sample t-test or one-way analysis of variance. Cumulative survival rates and cumulative mortalities associated with major causes were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared by the log-rank test. The Cox regression model was employed for the analysis of factors related to survival. Variables reaching statistical significance (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were incorporated into a multivariate analysis as covariates. Two-tailed P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS 21.0 package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients

Two hundred and fifty-six patients with confirmed diagnoses of primary BCS were analyzed, including 153 males and 103 females with a median age of 41 (range, 7-80) years. The baseline characteristics of the 256 patients are shown in Table 1 according to treatment modality. Furthermore, the patients were divided into two groups according to whether they received treatment or not, and their baseline characteristics were compared. The treated and untreated groups had statistically significant differences in the presentation of hepatic encephalopathy (P = 0.017), the pattern of IVC obstruction (P = 0.016), and portal vein thrombosis (P = 0.047).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 256 patients

| Medicine | Surgery | Intervention | Untreated | |

| Total number | 30 | 14 | 178 | 34 |

| Demographic data | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 16 | 4 | 109 | 24 |

| Female | 14 | 10 | 69 | 10 |

| Age (yr)1 | 36 (7-74) | 35 (24-47) | 41 (14-80) | 44.5 (14-66) |

| Duration of symptoms | ||||

| ≤ 1 mo | 5 | 0 | 28 | 7 |

| 1-6 mo | 7 | 2 | 35 | 12 |

| ≥ 6 mo | 18 | 12 | 115 | 15 |

| Clinical manifestations | ||||

| Abdominal distention | 24 | 12 | 82 | 15 |

| Abdominal wall varicosis | 12 | 13 | 105 | 16 |

| Lower-extremity edema | 17 | 13 | 104 | 17 |

| Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding | 8 | 3 | 26 | 4 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Laboratory tests12 | ||||

| Hemoglobin level (g/L) | 133 (64-172) | 149 (101-176) | 130.5 (30-180) | 134 (80-180) |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 130 (49-479) | 92 (47-160) | 108.5 (33-603) | 139.5 (50-341) |

| Alanine transaminase level (× ULN) | 0.6 (0.2-7.6) | 0.6 (0.3-1.6) | 0.6 (0.2-28) | 0.7 (0.3-3.6) |

| Albumin level (g/L) | 34.5 (13.1-54) | 36 (22-41) | 37.4 (16.7-57.7) | 35 (16-58) |

| Total bilirubin level (μmol/L) | 26.2 (6-146.2) | 28.6 (17.1-68.4) | 26 (7-292) | 24.9 (6.1-168) |

| International normalized ratio | 1.4 (0.9-1.9) | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | 1.3 (0.9-2.9) | 1.3 (0.9-1.8) |

| Creatinine level (μmol/L) | 106.3 (85-341) | 74 (71-77) | 74.1 (30-254) | 75 (29.6-146) |

| Blood urea nitrogen level (mmol/L) | 5.3 (1.8-26.6) | 5.1 (2.5-18.6) | 5.3 (2.5-39.1) | 5.6 (3.6-11.8) |

| Imaging features | ||||

| Type of obstruction | ||||

| HV | 9 | 0 | 25 | 10 |

| IVC | 3 | 2 | 41 | 9 |

| Com | 18 | 12 | 112 | 15 |

| Pattern of IVC obstruction | ||||

| No obstruction | 7 | 0 | 25 | 10 |

| Membranous | 14 | 8 | 108 | 15 |

| Segmental | 8 | 4 | 36 | 4 |

| Long segmental | 1 | 2 | 9 | 5 |

| Ascites | 17 | 9 | 85 | 14 |

| AHV compensation | 1 | 3 | 34 | 4 |

| IVC thrombosis | 11 | 5 | 57 | 14 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Prognostic index | ||||

| Child-Pugh score12 | 7 (5-9) | 6 (5-7) | 7 (5-12) | 6 (5-11) |

| Child-Pugh class2 | ||||

| A | 3 | 1 | 59 | 6 |

| B | 6 | 1 | 61 | 4 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

Data are shown as median with range in parentheses;

Data are incomplete because some laboratory tests were not performed prior to the year 2000. Except where indicated, data are shown as number of patients. ULN: Upper limit of normal; HV: Hepatic vein; IVC: Inferior vena cava; Com: Combination; AHV: Accessory hepatic vein.

Treatment

Except for 34 untreated patients, 222 patients received treatment, including 30 treated by medicine, 14 by surgery, and 178 by interventional radiology. Detailed information is presented in Table 2 for the 14 patients treated by surgical operations and the 178 patients treated by interventional procedures. For the patients treated by interventional radiology, the procedures were successful in 172 (96.6%) patients and failed in 6 patients due to diffuse HV obstruction (n = 4) and long segments (more than 5 cm) of IVC obstruction (n = 2). For the patients who experienced procedure-related complications, one died of disseminated intravascular coagulation 6 h after PTA, one died of severe hemoptysis of bronchiectasis 72 h after thrombolysis, one had stent fracture and was treated by implantation of an additional stent, and the other patients were given symptomatic treatment.

Table 2.

Detailed information on surgical operations and interventional procedures

| Department | Operations/procedures | No. | Complications |

| Surgery | Cavoatrial shunt | 10 | Hemorrhagic shock (n = 1) |

| Radical resection | 1 | ||

| Meso-cavo-atrial shunt | 1 | Acute hepatic failure (n = 1) | |

| Splenopneumopexy | 1 | ||

| Splenocaval shunt | 1 | ||

| Interventional radiology | Technic failure | 6 | |

| PTA | 96 | Abdominal pain (n = 4), DIC (n = 1) | |

| PTA combined with stent | 69 | Abdominal pain (n = 2), Stent fracture (n = 1), Supraventricular tachycardia (n = 2) | |

| TIPS | 7 | ||

| Catheter directed thrombolysis | 191 | Hematuria (n = 2), Hemoptysis (n = 1) |

The total number of patients treated by interventional procedures was 178, and the 19 patients treated by catheter directed thrombolysis were repeatedly counted among the patients treated by PTA (n = 5) and PTA combined with stent implantation (n = 14). PTA: Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; DIC: Disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Follow-up

Forty-four patients were lost to follow-up, and 212 patients were followed with a median period of 89 (0.2-360) mo; 67 of the followed patients died, with a median follow-up period of 28 (0.2-289) mo. The deaths of five patients who suffered from intracranial hemorrhage induced by hypertension (n = 1), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 1), disseminated intravascular coagulation (n = 1), accidental death (n = 1), and hemoptysis (n = 1) were not considered to be related to BCS. Detailed follow-up information is shown in Table 3. Regarding the remission of symptoms, symptoms were relieved in 107 out of 132 living patients in the treated group, and the overall remission rate was 81.1%; for the untreated group, 6 out of the 13 living patients were relieved of symptoms, and the remission rate was 46.2%. The difference between these two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.009). Furthermore, the comparison of loss rates between these two groups was not significantly different (P = 0.052). It was notable that the loss rate of the untreated group was 29.4% (10/34), which was higher than 20%.

Table 3.

Follow-up results of 256 Budd-Chiari syndrome patients

| Treatment | Total | Lost | Death | Remission | Non-remission/progression |

| Medicine | 30 | 16 | Variceal bleeding (n = 4), liver or multiple organ failure (n = 3), and hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1) | 3 | Abdominal distention (n = 3) |

| Surgery | 14 | 5 | Liver or multiple organ failure (n = 3), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1), variceal bleeding (n = 1), anastomotic infection (n = 1), and hepatic encephalopathy (n = 1) | 1 | Abdominal distention (n = 1) |

| Interventional radiology | |||||

| Technic failure | 6 | 0 | Liver or multiple organ failure (n = 3) | 1 | Abdominal distention (n = 1) and lower-extremity edema (n = 1) |

| PTA | 96 | 6 | Liver or multiple organ failure (n = 8), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 5), variceal bleeding (n = 3), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 1), intracranial hemorrhage induced by hypertension (n = 1), DIC (n = 1), and accidental death (n = 1) | 57 | Abdominal distention (n = 7), lower-extremity edema (n = 4), and lower-extremity varix (n = 2) |

| PTA combined with stent placement | 69 | 5 | Liver or multiple organ failure (n = 7), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 3), variceal bleeding (n = 2), hepatic encephalopathy (n = 2), and hemoptysis (n = 1) | 44 | Abdominal distention (n = 3), lower-extremity edema (n = 1), and muscle wasting (n = 1) |

| TIPS | 7 | 2 | Liver or multiple organ failure (n = 2), and variceal bleeding (n = 1) | 1 | Jaundice (n = 1) |

| Untreated | 34 | 10 | Liver or multiple organ failure (n = 7), variceal bleeding (n = 1), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1), hepatic encephalopathy (n = 1), and chronic leukemia (n = 1) | 6 | Abdominal distention (n = 4), muscle wasting (n = 2), and lower-extremity edema (n = 1) |

PTA: Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; DIC: Disseminated intravascular coagulation.

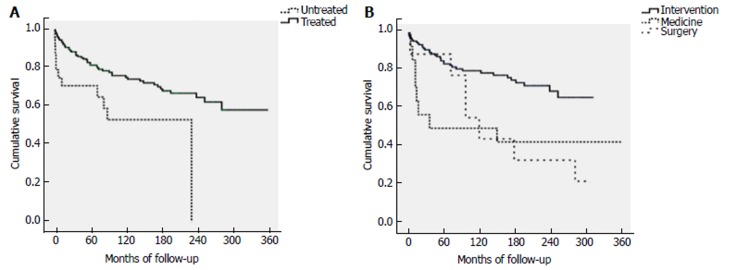

Survival

The cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year survival rates of the 188 treated patients were 93.5%, 81.6%, 75.2%, 64.7%, and 58.2%, respectively; for the 24 untreated patients, the 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year survival rates were 70.8%, 70.8%, 53.1%, 0%, and unavailable, respectively. The difference in cumulative survival rates between these two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.007) (Figure 2A). Regarding the different treatment modalities, the cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year survival rates of patients treated by interventional radiology were 95.7%, 85.3%, 80.2%, 69.5%, and unavailable, respectively; the 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year rates of patients treated by medicine were 85.7%, 50%, 50%, 50%, and 50%, respectively; and the 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year rates of patients treated by surgery were 88.9%, 88.9%, 44.4%, 33.3%, and unavailable, respectively. The difference in cumulative survival rates among these three treatment modalities was statistically significant (P = 0.002) (Figure 2B). The factors related to survival, excluding the five deaths unrelated to BCS, were analyzed in the treated patients. In univariate analysis, the predictors of survival included gastroesophageal variceal bleeding, a high level of alanine transaminase, ascites, and restenosis. In multivariate analysis, the independent predictors of survival were gastroesophageal variceal bleeding (HR = 3.043, 95%CI: 1.363-6.791, P = 0.007) and restenosis (HR = 4.610, 95%CI: 1.916-11.091, P = 0.001) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Survival rates of Budd-Chiari syndrome patients. A: Comparison of cumulative survival rates of Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) between the 188 treated patients and 24 untreated patients. Treated patients had significantly better long-term survival than untreated patients (P = 0.007); B: Comparison of cumulative survival rates of BCS among different treatment modalities. Patients treated by interventional radiology had significantly better long-term survival than patients treated by medicine or surgery (P = 0.002).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the predictors of survival for treated patients

| Variable |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.558 | 0.297-1.050 | 0.071 | |||

| Age | 0.992 | 0.968-1. 017 | 0.550 | |||

| History of BCS since first presentation | 0.994 | 0.987-1.000 | 0.055 | |||

| Abdominal distention (Yes/No) | 0.943 | 0.531-1.643 | 0.813 | |||

| Abdominal wall varicosis (Yes/No) | 0.819 | 0.461-1.457 | 0.497 | |||

| Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding (Yes/No) | 2.928 | 1.647-5.270 | < 0.001 | 3.043 | 1.363-6.791 | 0.007 |

| Lower-extremity edema (Yes/No) | 1.318 | 0.757-2.294 | 0.330 | |||

| Hemoglobin level | 0.994 | 0.983-1.005 | 0.311 | |||

| Platelet count | 1.002 | 0.998-1.006 | 0.308 | |||

| Alanine transaminase level | 1.003 | 1.001-1.005 | 0.005 | 1.002 | 0.999-1.005 | 0.274 |

| Albumin level | 0.975 | 0.928-1.024 | 0.307 | |||

| Total bilirubin level | 1.007 | 0.997-1.017 | 0.183 | |||

| INR | 1.280 | 0.367-4.468 | 0.699 | |||

| Creatinine level | 1.005 | 0.991-1.019 | 0.489 | |||

| Blood urea nitrogen level | 1.049 | 0.971-1.133 | 0.225 | |||

| Ascites (Yes/No) | 2.108 | 1.205-3.686 | 0.009 | 1.849 | 0.812-4.213 | 0.143 |

| Accessory hepatic vein (Yes/No) | 2.126 | 0.842-5.366 | 0.110 | |||

| Associated IVC thrombosis (Yes/No) | 1.000 | 0.553-1.809 | 0.999 | |||

| Restenosis (Yes/No) | 5.309 | 2.378-11.852 | < 0.001 | 4.610 | 1.916-11.091 | 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh score | 1.108 | 0.852-1.440 | 0.444 | |||

HR: Hazard ratio; BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome; INR: International normalized ratio; IVC: Inferior vena cava.

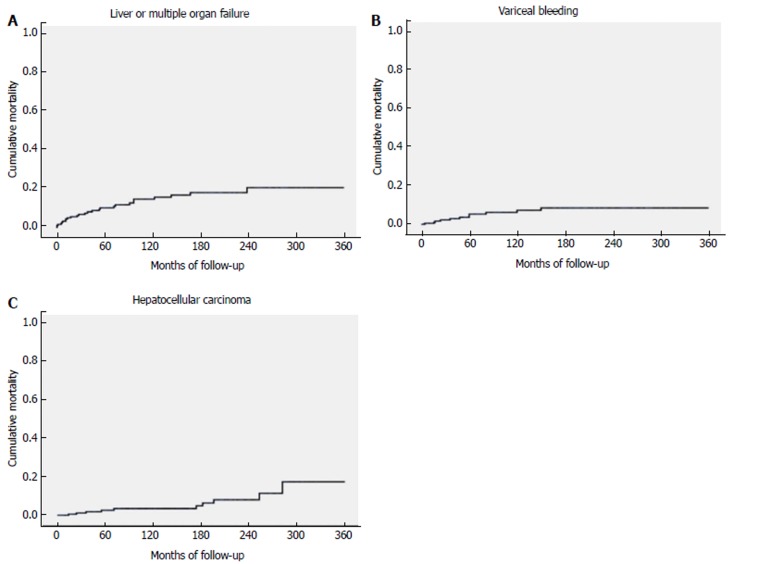

Cumulative mortalities of major causes

For the treated patients, the major causes of death were liver or multiple organ failure (n = 26), gastroesophageal variceal bleeding (n = 11), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (n = 10), which accounted for more than 80% of the total deaths (83.9%). The median survival time was 37.5 (1-239) mo for patients who died of liver or multiple organ failure, 48 (4-150) mo for patients who died of gastroesophageal variceal bleeding, and 122.5 (14-282) mo for patients who died of HCC. The difference in survival times across these three groups was statistically significant (P = 0.016). The cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year mortality rates for liver or multiple organ failure were 4.4%, 10.1%, 14.5%, 20.5%, and 20.5%, respectively (Figure 3A); the 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year mortality rates for gastroesophageal variceal bleeding were 0.5%, 5.3%, 7.3%, 8.5%, and 8.5%, respectively (Figure 3B); and the 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year mortality rates for HCC were 0%, 2.6%, 3.5%, 8%, and 17.4%, respectively (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Cumulative mortality rates of Budd-Chiari syndrome. A: Cumulative mortality rates of Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) patients who died of liver or multiple organ failure; B: Cumulative mortality rates of BCS patients who died of gastroesophageal variceal bleeding; C: Cumulative mortality rates of BCS patients who died of hepatocellular carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first large case series that evaluated interventional treatment outcomes of Chinese BCS patients with more than 20-year follow-up. We assume that most Chinese BCS patients are characterized by insidious onset and chronic development[22,25,26]; therefore, a relatively long time is needed to observe long-term outcomes. However, the follow-up time span that can be defined as “long-term follow-up” is still debatable. According to our study, we found that deaths greatly increased after 10-year follow-up, especially those of patients who died of HCC. Therefore, we suggest that the long-term follow-up span should not be less than 10 years for Chinese BCS patients.

In the present study, patients were retrospectively divided into a treated group and an untreated group according to whether the patients received treatment or not. Less than half of the patients who did not receive any regular treatments (medicine, surgery, or interventional radiology) had intermittent, spontaneous relief of clinical symptoms, and none survived for more than 20 years. These findings were very interesting because the follow-up results might reflect the natural outcomes of Chinese BCS patients. According to our results, the natural survival of Chinese BCS patients seemed to be better than that of Western patients, for whom it was estimated that 90% of untreated patients would die within 3 years[2,27]. The follow-up results also suggested that timely intervention was crucial for the survival of BCS patients, even if their symptoms could be spontaneously intermittently relieved. It was noteworthy that the loss rate was higher than 20% for untreated patients; therefore, the findings that reflected the natural outcomes of Chinese BCS patients should be carefully interpreted.

The cumulative survival rates of the treated group were better than those of the untreated group. However, some baseline characteristics between these two groups were different (the presentation of hepatic encephalopathy and portal vein thrombosis was higher in the untreated group than in the treated group, indicating a more serious condition). For the patients treated by interventional radiology, the cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, and 20-year survival rates were 95.7%, 85.3%, 80.2%, and 69.5%, respectively. The cumulative 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates were excellent and comparable to the results recently reported from a systematic review, which found that the median 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates were 93%, 83%, and 73% after interventional radiological treatments, respectively[28]. The cumulative 20-year survival rate of patients treated by intervention radiology was significantly better than that of patients treated by medicine or surgery (69.5% vs 50% or 33.3%, respectively), which supported wide future use of interventional radiological procedures as a treatment modality. Furthermore, the cumulative 20- and 30-year survival rates of the treated patients were 64.7% and 58.2%, which were satisfying for such a rare disease with chronic history. Of note, the actual survival rates of patients treated by medicine and surgery in our study were influenced by the high ratio of patients lost to follow-up (more than 50%) and should be cautiously interpreted.

According to previous studies, the causes of death of BCS patients mainly included liver failure, gastroesophageal bleeding, HCC, hepatic encephalopathy, and chronic leukemia[5,10,29]. The present study demonstrated that the major cause of death was liver or multiple organ failure, which accounted for 46% (26/56) of the total deaths of treated patients, and this proportion was relatively high compared with results from previous studies[5,6,10]. We explored the possible reasons for this relatively higher occurrence of liver or multiple organ failure by further calculating its cumulative mortality and found that liver or multiple organ failure occurred more frequently within 5 years after primary treatments, which was longer than the 2-year time-frame reported in a previous study[5]. One possible explanation is that for Chinese BCS patients, the chronic development course may allow formation of HV collateral circulation or accessory HV compensation, which might slow down the occurrence of liver failure but simultaneously increases the number of patients who are prone to liver failure.

Another major cause of death that we focused on was HCC. It occurred in 10 of the 188 treated patients, and the median time of survival was 122.5 (14-282) mo, which indicated that it was a chronic complication of BCS. This result agreed with previous studies and demonstrated that HCC was a chronic complication of BCS and mostly occurred over a relatively long time[30-32]. A recent study demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of HCC was 3.5% at 10 years, and the risk factors related to HCC development were liver cirrhosis, combined IVC and HV block, and long-segment IVC block. The authors found that association of these three events with occurrence of HCC would indicate that degree and extent of outflow obstruction, and presence of advanced degree of fibrosis suggesting prolonged hepatic congestion with resultant parenchymal loss were associated with HCC development[33].

In our study, 10 patients experienced HCC and died during 30-year follow-up, and this incidence was higher than that in the above mentioned study (8 out of 413 patients during 20-year follow-up). In addition, we further calculated the cumulative mortality of HCC and found that the cumulative 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 30-year mortality rates were 0%, 2.6%, 3.5%, 8%, and 17.4%, respectively. This result also demonstrated that the incidence and number of patients who died of HCC progressively increased over time, which is consistent with the results of the above mentioned study.

One major limitation of our study was its retrospective nature. Some of the earlier original data (especially before the year 2000) were not recorded or lost. In addition, although a regular follow-up schedule was established and we tried our best to stay in contact with all BCS patients, approximately 17% (44/256) of the total patients were lost to follow-up, and this proportion was even higher (more than 50%) in patients treated by medicine or surgery. One possible explanation is that most of the lost patients were admitted in a relatively early period (before 2002) when follow-up was very difficult, especially for patients in poverty or remote regions. Another limitation was that the baseline data of patients treated by different modalities were inhomogeneous; thus, subgroup analysis was inappropriate.

In conclusion, the long-term survival of Chinese BCS patients was satisfactory for treated patients, especially for patients treated by interventional procedures. Restenosis and gastroesophageal variceal bleeding were critical factors for predicting long-term survival. Long-term follow-up should not be less than 10 years to monitor the chronic complications of HCC.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare disease. For Asian patients, especially Chinese patients, the predominant obstructive lesions are membranous and segmental obstructions of the supra-hepatic or retro-hepatic portion of the inferior vena cava. Till the year 2014, more than 20000 cases of BCS have been published in China, and interventional radiological procedures (mainly percutaneous re-canalization) have become the most common treatment option. However, outcomes from more than 10-year follow-up are scarcely reported for Chinese BCS patients.

Research motivation

As Chinese BCS patients are characterized by insidious onset and chronic development, ten years may not be long enough for long-term outcome observations. We want to find the 20-year and 30-year survival rates at our single center, which may represent the Chinese BCS population to a certain extent. Furthermore, for the chronic complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, the incidence and mortality of Chinese BCS patients are still unknown, and we are very interested in these issues.

Research objectives

The objectives were to analyze a 30-year follow-up outcome Chinese BCS patients in a single Chinese center, specifically, to find the 20-year and 30-year cumulative survival rates for the different treatment modalities applied in our center; to find the factors related to long-term survival; and to calculate the cumulative mortalities of major causes.

Research methods

We retrospectively analyzed a 30-year follow-up outcome of BCS patients at our center. Medical records of 410 patients treated between November 1983 and September 2013 with an admission diagnosis of BCS were identified in our hospitalization register system. Only the primary hospitalization medical records were enrolled. Finally, 256 patients were eligible for our study. In this case series, 34 patients were untreated (did not receive any regular treatments) and 222 patients received treatment, including 30 treated by medicine, 14 by surgery, and 178 by interventional radiology. Patients were followed until the end of this study (December 31, 2014). Symptom remission was defined as complete remission or substantial partial remission of the main symptoms that the patients complained about most urgently. Patients were examined by color Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging for restenosis evaluation, and the results were confirmed by venography at our hospital. Cumulative survival rates and cumulative mortalities associated with major causes were analyzed. The Cox regression model was employed for the analysis of factors related to survival. Variables reaching statistical significance in the univariate analysis were incorporated into a multivariate analysis as covariates. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Research results

About 212 patients (44 were lost to follow-up) were followed with a median time of 89 (0.2-360) mo; 67 of the followed patients died, with a median follow-up period of 28 (0.2-289) mo. A statistically significant difference was found in cumulative survival rates between these two groups. A statistically significant difference was also found in cumulative survival rates among these three treatment modalities. The independent predictors of survival were gastroesophageal variceal bleeding and restenosis. For the treated patients, the major causes of death were liver or multiple organ failure, gastroesophageal variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which accounted for more than 80% of the total deaths.

Research conclusions

The present study is the first large case series that evaluated interventional treatment outcomes of Chinese BCS patients with more than 20-year follow-up, to the best of our knowledge. We suggest that the long-term follow-up span should not be less than 10 years for Chinese BCS patients. Less than half of the patients had intermittent, spontaneous relief of clinical symptoms, and none survived for more than 20 years. Restenosis and gastroesophageal variceal bleeding were critical factors for predicting the long-term survival. To monitor the chronic complications of BCS such as HCC, long-term follow-up should not be less than 10 years.

Research perspectives

In future studies, prospective and multi-center research should be encouraged to overcome the high rate of loss and to do the subgroup analysis.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: All study participants provided written informed consent for personal and medical data collection prior to study enrollment and each patient agreed to management via written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Data sharing statement: The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author at kexu@vip.sina.com. The participants gave informed consent for the data sharing.

Peer-review started: December 8, 2017

First decision: December 20, 2017

Article in press: January 24, 2018

P- Reviewer: Elsiesy H, Gad EH, Garbuzenko DV, Tahiri MJT S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Wei Zhang, Department of Interventional Radiology, Shenzhen People’s Hospital, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Shenzhen 518020, Guangdong Province, China; Department of Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China; Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional Radiology of Liaoning Province, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China.

Qiao-Zheng Wang, Department of Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China.

Xiao-Wei Chen, Department of Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China; Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional Radiology of Liaoning Province, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China.

Hong-Shan Zhong, Department of Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China; Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional Radiology of Liaoning Province, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China.

Xi-Tong Zhang, Department of Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China.

Xu-Dong Chen, Department of Interventional Radiology, Shenzhen People’s Hospital, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Shenzhen 518020, Guangdong Province, China.

Ke Xu, Department of Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China. kexu@vip.sina.com; Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional Radiology of Liaoning Province, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China.

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Vascular diseases of the liver. J Hepatol. 2016;64:179–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valla DC. Primary Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol. 2009;50:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valla DC. Hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction etiopathogenesis: Asia versus the West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:S204–S211. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plessier A, Sibert A, Consigny Y, Hakime A, Zappa M, Denninger MH, Condat B, Farges O, Chagneau C, de Ledinghen V, et al. Aiming at minimal invasiveness as a therapeutic strategy for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hepatology. 2006;44:1308–1316. doi: 10.1002/hep.21354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seijo S, Plessier A, Hoekstra J, Dell’era A, Mandair D, Rifai K, Trebicka J, Morard I, Lasser L, Abraldes JG, et al. Good long-term outcome of Budd-Chiari syndrome with a step-wise management. Hepatology. 2013;57:1962–1968. doi: 10.1002/hep.26306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darwish Murad S, Plessier A, Hernandez-Guerra M, Fabris F, Eapen CE, Bahr MJ, Trebicka J, Morard I, Lasser L, Heller J, Hadengue A, Langlet P, Miranda H, Primignani M, Elias E, Leebeek FW, Rosendaal FR, Garcia-Pagan JC, Valla DC, Janssen HL; EN-Vie (European Network for Vascular Disorders of the Liver) Etiology, management, and outcome of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:167–175. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okuda K, Kage M, Shrestha SM. Proposal of a new nomenclature for Budd-Chiari syndrome: hepatic vein thrombosis versus thrombosis of the inferior vena cava at its hepatic portion. Hepatology. 1998;28:1191–1198. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang ZG, Zhang FJ, Yi MQ, Qiang LX. Evolution of management for Budd-Chiari syndrome: a team’s view from 2564 patients. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilawari JB, Bambery P, Chawla Y, Kaur U, Bhusnurmath SR, Malhotra HS, Sood GK, Mitra SK, Khanna SK, Walia BS. Hepatic outflow obstruction (Budd-Chiari syndrome). Experience with 177 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1994;73:21–36. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han G, Qi X, Zhang W, He C, Yin Z, Wang J, Xia J, Xu K, Guo W, Niu J, et al. Percutaneous recanalization for Budd-Chiari syndrome: an 11-year retrospective study on patency and survival in 177 Chinese patients from a single center. Radiology. 2013;266:657–667. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathod K, Deshmukh H, Shukla A, Popat B, Pandey A, Gupte A, Gupta DK, Bhatia SJ. Endovascular treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome: Single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:237–243. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Qi X, Zhang X, Su H, Zhong H, Shi J, Xu K. Budd-Chiari Syndrome in China: A Systematic Analysis of Epidemiological Features Based on the Chinese Literature Survey. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:738548. doi: 10.1155/2015/738548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shenyang Branch of Internal Medicine Institute of Chinese Medical Association and Department of Pathology of Shenyang Medical College. Discussion of clinical pathology: case No. 32. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 1957;5:166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi XS, Ren WR, Fan DM, Han GH. Selection of treatment modalities for Budd-Chiari Syndrome in China: a preliminary survey of published literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10628–10636. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tripathi D, Sunderraj L, Vemala V, Mehrzad H, Zia Z, Mangat K, West R, Chen F, Elias E, Olliff SP. Long-term outcomes following percutaneous hepatic vein recanalization for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver Int. 2017;37:111–120. doi: 10.1111/liv.13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang QQ, Xu H, Zu MH, Gu YM, Shen B, Wei N, Xu W, Liu HT, Wang WL, Gao ZK. Strategy and long-term outcomes of endovascular treatment for Budd-Chiari syndrome complicated by inferior vena caval thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang CQ, Fu LN, Xu L, Zhang GQ, Jia T, Liu JY, Qin CY, Zhu JR. Long-term effect of stent placement in 115 patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2587–2591. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiao T, Liu CJ, Liu C, Chen K, Zhang XB, Zu MH. Interventional endovascular treatment for Budd-Chiari syndrome with long-term follow-up. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:318–326. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.10947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng X, Lv Y, Zhang B, He C, Guo W, Luo B, Yin Z, Fan D, Han G. Endovascular Management of Budd-Chiari Syndrome with Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis: A 14-Year Single-Center Retrospective Report of 55 Patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:1592–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding PX, Li Z, Zhang SJ, Han XW, Wu Y, Wang ZG, Fu MT. Outcome of the Z-expandable metallic stent for Budd-Chiari syndrome and segmental obstruction of the inferior vena cava. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:972–979. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang XM, Li QL. Etiology, treatment, and classification of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:159–161. doi: 10.3901/jme.2007.04.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng D, Xu H, Lu ZJ, Hua R, Qiu H, Du H, Xu X, Zhang J. Clinical features and etiology of Budd-Chiari syndrome in Chinese patients: a single-center study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1061–1067. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang ZG, Jones RS. Budd-Chiari syndrome. Curr Probl Surg. 1996;33:83–211. doi: 10.1016/s0011-3840(96)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu K, Feng B, Zhong H, Zhang X, Su H, Li H, Zhao Z, Zhang H. Clinical application of interventional techniques in the treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:609–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dang X, Li L, Xu P. Research status of Budd-Chiari syndrome in China. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:4646–4652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan JG, Wang FS. Difference of Budd-Chiari syndrome between West and China. Hepatology. 2014;62:657. doi: 10.1002/hep.27628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tavill AS, Wood EJ, Kreel L, Jones EA, Gregory M, Sherlock S. The Budd-Chiari syndrome: correlation between hepatic scintigraphy and the clinical, radiological, and pathological findings in nineteen cases of hepatic venous outflow obstruction. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:509–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi X, Ren W, Wang Y, Guo X, Fan D. Survival and prognostic indicators of Budd-Chiari syndrome: a systematic review of 79 studies. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:865–875. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1024224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eapen CE, Velissaris D, Heydtmann M, Gunson B, Olliff S, Elias E. Favourable medium term outcome following hepatic vein recanalisation and/or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for Budd Chiari syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:878–884. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.071423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moucari R, Rautou PE, Cazals-Hatem D, Geara A, Bureau C, Consigny Y, Francoz C, Denninger MH, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Budd-Chiari syndrome: characteristics and risk factors. Gut. 2008;57:828–835. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.139477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren W, Qi X, Yang Z, Han G, Fan D. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in Budd-Chiari syndrome: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:830–841. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835eb8d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakr M, Abdelhakam SM, Dabbous H, Hamed A, Hefny Z, Abdelmoaty W, Shaker M, El-Gharib M, Eldorry A. Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptian patients with primary Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver Int. 2017;37:415–422. doi: 10.1111/liv.13219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul SB, Shalimar, Sreenivas V, Gamanagatti SR, Sharma H, Dhamija E, Acharya SK. Incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:961–971. doi: 10.1111/apt.13173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]