Abstract

Background

Elevated levels of osteoprotegerin, a secreted tumor necrosis factor–related molecule, might be associated with adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. We measured plasma osteoprotegerin concentrations on hospital admission, at discharge, and at 1 and 6 months after discharge in a predefined subset (n=5135) of patients with acute coronary syndromes in the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial.

Methods and Results

The associations between osteoprotegerin and the composite end point of cardiovascular death, nonprocedural spontaneous myocardial infarction or stroke, and non–coronary artery bypass grafting major bleeding during 1 year of follow‐up were assessed by Cox proportional hazards models. Event rates of the composite end point per increasing quartile groups at baseline were 5.2%, 7.5%, 9.2%, and 11.9%. A 50% increase in osteoprotegerin level was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.31 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.21–1.42) for the composite end point but was not significant in adjusted analysis (ie, clinical characteristics and levels of C‐reactive protein, troponin T, NT‐proBNP [N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide], and growth differentiation factor‐15). The corresponding rates of non–coronary artery bypass grafting major bleeding were 2.4%, 2.2%, 3.8%, and 7.2%, with an unadjusted HR of 1.52 (95% CI, 1.36–1.69), and a fully adjusted HR of 1.26 (95% CI, 1.09–1.46). The multivariable association between the osteoprotegerin concentrations and the primary end point after 1 month resulted in an HR of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.89–1.33); for major bleeding after 1 month, the HR was 1.33 (95% CI, 0.91–1.96).

Conclusions

In patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with dual antiplatelet therapy, osteoprotegerin was an independent marker of major bleeding but not of ischemic cardiovascular events. Thus, high osteoprotegerin levels may be useful in increasing awareness of increased bleeding risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome receiving antithrombotic therapy.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00391872.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, bleeding, osteoprotegerin, prognosis

Subject Categories: Myocardial Infarction, Mortality/Survival, Atherosclerosis, Inflammation

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

In patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with dual antiplatelet therapy, osteoprotegerin was an independent marker of major bleeding after adjustment for clinical risk factors and multiple biomarkers prognostic for both cardiovascular events and bleeding, but it was not a marker of ischemic cardiovascular events.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

High osteoprotegerin levels may be useful in increasing awareness of increased bleeding risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome receiving antithrombotic therapy.

Osteoprotegerin, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, exerts pleiotropic effects on bone metabolism, endocrine function, and vascular inflammation,1 at least partly through acting as a decoy receptor for the receptor activator of nuclear factor‐κB ligand.1 Osteoprotegerin may colocalize with von Willebrand factor (vWF) in platelets and on endothelial cells and is rapidly released by inflammatory stimuli.2, 3, 4 Furthermore, osteoprotegerin is expressed within the failing myocardium in both experimental and clinical heart failure,5 and osteoprotegerin expression has been observed in thrombotic material obtained from the site of plaque rupture during myocardial infarction (MI).6 Thus, osteoprotegerin seems to be a multifaceted mediator with relevance for vascular and atherosclerotic disorders, although details of its pathways of actions are still sparsely understood.2, 3, 4

Circulating biomarkers provide independent information on risk for adverse outcomes on top of established demographic and clinical variables in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACSs).7, 8, 9, 10, 11 In addition to the established natriuretic peptides and cardiac troponins, which have been extensively evaluated and shown to be suitable biomarkers for prognosis and/or risk stratification of ACS,12, 13 the recently characterized inflammatory marker, growth differentiation factor‐15 (GDF‐15), may also provide additional clinically useful prognostic information in ACS.14 Also, cystatin C, a marker of kidney function, has recently gained increasing relevance as an independent marker of mortality in ACS.15 Accordingly, we have recently shown that NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide),9, 10 high‐sensitivity troponin T (hs‐TnT),9, 10 GDF‐15,8, 9, 10 and cystatin C7 display independent associations with cardiovascular outcomes, including cardiovascular death, in the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial. Therefore, they represent important adjustment variables for evaluating the independent contribution of new biomarkers to prognosis.

Elevated osteoprotegerin levels have similarly been associated with all‐cause mortality16, 17 and cardiovascular outcomes, like MI18 and heart failure,19 in patients with established coronary artery disease or ACS. In addition to the potential modulatory role of osteoprotegerin on hemostasis through interactions with vWF, elevated circulating osteoprotegerin concentrations have been associated with increased risk of bleeding complications in patients with polycythemia vera,4 a condition with increased risk of both thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications. Nonetheless, the clinical importance of osteoprotegerin as a risk factor of bleeding complications has never been reported in patients with ACS.8

The PLATO trial encompassed a broad ACS population and proved ticagrelor to be superior to clopidogrel in reducing the composite end point of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or stroke. There was no difference in the overall rates of major bleeding, but there was an increase in bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).20, 21 In the current PLATO trial substudy, we evaluated osteoprotegerin levels on hospital admission and during 6 months of follow‐up after ACS, together with important prognostic biomarkers, in relation to the composite end point of cardiovascular death, spontaneous MI, and stroke as well as to major non–CABG‐related bleeding.20, 21 Finally, we explored the changes over time in osteoprotegerin concentrations from admission through 6 months of follow‐up.

Methods

Design and Study Population

The randomized placebo‐controlled PLATO trial included a total of 18 624 patients with ACS.20, 21 The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. The patients presented with either ST‐segment–elevation (STE) ACS or non‐STE ACS and were randomized to either clopidogrel or ticagrelor treatment in addition to optimal medical therapy, including aspirin, and optional invasive therapy.20, 21 The need for additional oral anticoagulant therapy (ie, triple therapy) after inclusion was a contraindication in the PLATO trial. Patients were recruited between October 11, 2006 and July 17, 2008, and were followed up for up to 12 months after ACS.

Venous blood samples were obtained from all patients at randomization as part of the main study. In addition, there was a predefined substudy with serial blood sampling conducted at selected sites aiming to obtain samples from 4000 patients at hospital discharge and after 1 month and from at least 3000 of these patients also at 6 months.20, 21 All patients at these selected sites were continuously invited to the substudy, and inclusion of new patients proceeded until it was estimated that at least 3000 patients would be available for blood sampling at 6 months. Patients with a blood sample at baseline and at least 1 additional blood sample during follow‐up were eligible for inclusion in the current analyses. The overall aims of the biomarker substudy program have previously been published.20, 21 The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, the research protocol was approved by national and institutional regulatory and ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

End Point Definition and Follow‐Up

The prespecified primary end point of the present substudy was the composite of cardiovascular death (defined as any cardiovascular cause of death, sudden death, or any death with no clear attributable noncardiovascular cause), spontaneous MI (defined as non–procedure‐related, nonfatal, MI type 122), or stroke within 1 year of follow‐up.20 The components of the composite end point were also evaluated separately. The secondary end point was PLATO‐defined non‐CABG major bleeding, defined as follows: bleeding that was fatal, bleeding that was intracranial, bleeding that required ≥2 U of blood transfusion, or bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin of >5 g/dL20 (but not if directly related to a CABG operation).20 All end points in the PLATO trial were centrally adjudicated by an independent and blinded clinical events adjudication committee (A.Å. and S.K.J.), comprising cardiologists or neurologists, to subclassify causes of death and to subdivide types of MI, stroke, and bleeding events.20, 22

Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

Baseline venous blood samples were obtained within 24 hours of admission, before the administration of study medication. The venous blood was centrifuged, and the plasma samples were locally frozen in aliquots and stored at −70°C in a central repository at Uppsala Biobank until biochemical analyses were performed. Osteoprotegerin concentrations were determined by enzyme‐linked immunoassay (R&D Systems, Stillwater, MN), as previously described and validated.23 Briefly, wells were coated overnight with monoclonal mouse anti‐human osteoprotegerin antibody in sterile PBS. The standard was recombinant osteoprotegerin. Subsequent steps included biotinylated polyclonal goat anti‐human osteoprotegerin, streptavidin horseradish peroxidase, and tetramethylbenzidine as substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific, By, MA). The mean recovery of 2 samples spiked with different concentrations of recombinant osteoprotegerin was 93%. The intra‐assay and interassay coefficients of variation of osteoprotegerin in the present study were 2.6% and 6.0%, respectively. The sensitivity, defined as the mean±3 SDs of the zero standard, was calculated to be 15 pg/mL.

Hs‐TnT, NT‐proBNP, and cystatin C were determined with sandwich immunoassays on the Cobas Analytics e601 Immunoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). White blood cell (WBC) count and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP) were analyzed at the UCR Laboratory (Uppsala, Sweden), with a spectrophotometric analysis (Architect; Abbott, IL). GDF‐15 was measured with a precommercial assay (Roche Diagnostics) using a monoclonal mouse antibody for capture and a monoclonal mouse antibody fragment for detection in a sandwich assay format. The results of these analyses in relation to outcomes and effects of study treatment have previously been reported.8, 9, 10

Statistical Analysis

Osteoprotegerin concentrations at all time points are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). The changes of osteoprotegerin concentration over time were tested by Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. Baseline characteristics are presented by osteoprotegerin quartile groups. Categorical baseline variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and compared by quartile groups of osteoprotegerin using χ2 tests. Continuous baseline variables are presented as medians and IQRs and compared by quartile groups of osteoprotegerin using the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Natural logarithmic transformations were performed for biomarker levels to obtain an approximate normal distribution. The relationship between osteoprotegerin and baseline characteristics and biomarkers was assessed by multivariable linear models. We calculated geometric means using the antilogarithms of the model‐adjusted means (ie, predicted marginal means) and subsequently compared geometric means between groups (eg, men/women) using ratios.

Crude event rates at 1 year, by osteoprotegerin quartile groups at baseline, were estimated, as were Kaplan‐Meier event rates. The functional form of the relationship between osteoprotegerin and outcomes was explored using cumulative sums of martingale residuals and restricted cubic splines.24 The associations of osteoprotegerin concentrations (logarithm transformed), on admission, with the composite end point of cardiovascular death, spontaneous MI, or stroke and the secondary end points of cardiovascular death and bleeding were assessed by multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. The hazard was based on a 50% increase in biomarker concentration. Six models, with incremental addition of covariates, were used. Model 1 included the randomized treatment (ticagrelor or clopidogrel). Model 2 added the following clinical baseline risk factors: age, sex, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, smoking status, type of ACS, and history of heart failure, MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG, stroke, or peripheral artery disease. Model 3 included all variables from model 2 together with hs‐CRP level and WBC count. Model 4 included all the previously mentioned covariates with the addition of cystatin C, a marker of kidney dysfunction, which is strongly associated with an adverse outcome in this population.7 Model 5 included all previously mentioned variables in addition to hs‐TnT and NT‐proBNP. Model 6 included all previously mentioned variables and GDF‐15. For end points where osteoprotegerin was significantly associated in model 6, discrimination was assessed using the Harrell C‐index. The multivariable models with and without osteoprotegerin were compared in terms of global model fit using likelihood ratio tests.

The effects of osteoprotegerin levels on outcomes in relation to predefined subgroup factors (ie, randomized treatment, ACS type, invasive/noninvasive in‐hospital treatment approach, diabetes mellitus, sex, and smoking) were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models. These models included quartile‐divided osteoprotegerin levels, the respective subgroup factor, and the osteoprotegerin subgroup factor interaction term as independent variables. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by visual inspection of Schoenfeld residual plots. A 2‐sided P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, and there were no adjustments for multiple comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Osteoprotegerin at Baseline and in Relation to Baseline Characteristics

Baseline osteoprotegerin concentrations were available in 5135 patients, with a median (IQR) of 2.65 (2.02–3.62) ng/mL. The blood samples for osteoprotegerin analysis were collected a median (IQR) of 15 (IQR, 8–21) hours after the index event or a median (IQR) of 10 (3–17) hours after admission.

The background characteristics for the entire study population with biomarkers available at baseline (n=16 401) have previously been reported.7 Baseline characteristics by osteoprotegerin quartile groups are presented in Table 1 and showed that higher osteoprotegerin levels were associated with several demographic features and several biomarkers. Multivariable linear regression identified increasing age, female sex, STE ACS, increasing levels of hs‐TnT, GDF‐15, hs‐CRP, and WBC, and lower cystatin C as the most prominent predictors of osteoprotegerin at baseline (Table 2). In contrast, the hs‐TnT level was not associated with osteoprotegerin levels at 1 month. Age, female sex, GDF‐15, and hs‐CRP were the strongest predictors of osteoprotegerin at 1 month.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Biomarkers by Quartiles of Osteoprotegerin Concentrations at Baseline

| Characteristic | Quartile 1 (<2.0 ng/mL) (n=1283) | Quartile 2 (2.0–2.7 ng/mL) (n=1284) | Quartile 3 (2.7–3.6 ng/mL) (n=1284) | Quartile 4 (>3.6 ng/mL) (n=1284) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 56 (50–63) | 62 (54–69) | 65 (56–72) | 67 (57–75) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 273 (21.3) | 361 (28.1) | 429 (33.4) | 474 (36.9) | <0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 82 (73–93) | 81 (72–90) | 80 (70–89) | 78 (68–90) | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.8 (25.3–30.8) | 27.8 (25.3–30.9) | 27.5 (24.8–30.4) | 27.2 (24.7–30.5) | 0.0005 |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Habitual smoker | 503 (39.2) | 500 (38.9) | 448 (34.9) | 440 (34.3) | 0.0104 |

| Hypertension | 787 (61.3) | 846 (65.9) | 884 (68.8) | 870 (67.8) | 0.0003 |

| Dyslipidemia | 569 (44.3) | 558 (43.5) | 551 (42.9) | 495 (38.6) | 0.0148 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 204 (15.9) | 255 (19.9) | 318 (24.8) | 364 (28.3) | <0.0001 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Angina pectoris | 623 (48.6) | 603 (47.0) | 618 (48.1) | 546 (42.5) | 0.0080 |

| Myocardial infarction | 250 (19.5) | 263 (20.5) | 259 (20.2) | 231 (18.0) | 0.3893 |

| Congestive heart failure | 45 (3.5) | 63 (4.9) | 81 (6.3) | 107 (8.3) | <0.0001 |

| PCI | 190 (14.8) | 179 (13.9) | 129 (10.0) | 136 (10.6) | 0.0002 |

| CABG | 51 (4.0) | 68 (5.3) | 71 (5.5) | 66 (5.1) | 0.2731 |

| TIA | 15 (1.2) | 29 (2.3) | 41 (3.2) | 28 (2.2) | 0.0066 |

| Nonhemorrhagic stroke | 34 (2.7) | 35 (2.7) | 57 (4.4) | 49 (3.8) | 0.0313 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 69 (5.4) | 84 (6.5) | 101 (7.9) | 92 (7.2) | 0.0776 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22 (1.7) | 31 (2.4) | 48 (3.7) | 78 (6.1) | <0.0001 |

| ST‐segment–elevation MI | 517 (40.3) | 571 (44.5) | 598 (46.6) | 666 (51.9) | <0.0001 |

| GRACE risk score | 124.0 (109–139) | 133.0 (117–149) | 137.0 (120–154) | 143.0 (126–162) | <0.0001 |

| In‐hospital medication | |||||

| Aspirin | 1263 (98.4) | 1266 (98.6) | 1259 (98.1) | 1264 (98.4) | 0.7270 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 661 (51.5) | 699 (54.4) | 691 (53.8) | 756 (58.9) | 0.0021 |

| LMWH | 714 (55.7) | 688 (53.6) | 702 (54.7) | 666 (51.9) | 0.2539 |

| Fondaparinux | 16 (1.2) | 24 (1.9) | 21 (1.6) | 12 (0.9) | 0.1946 |

| Bivalirudin | 21 (1.6) | 23 (1.8) | 16 (1.2) | 16 (1.2) | 0.5656 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 325 (25.3) | 329 (25.6) | 343 (26.7) | 368 (28.7) | 0.2135 |

| β Blockers | 1129 (88.0) | 1118 (87.1) | 1112 (86.6) | 1112 (86.6) | 0.6884 |

| ACE inhibition and/or ARB | 1103 (86.0) | 1092 (85.0) | 1131 (88.1) | 1136 (88.5) | 0.0265 |

| Cholesterol lowering (statin) | 1210 (94.3) | 1193 (92.9) | 1199 (93.4) | 1209 (94.2) | 0.4181 |

| Biomarkers | |||||

| Hs‐TnT, ng/L | 119.0 (30.2–353.0) | 158.0 (40.2–478.0) | 135.0 (33.2–505.0) | 274.5 (60.7–963.0) | <0.0001 |

| NT‐proBNP, pmol/L | 260 (102–593) | 402 (136–932) | 458 (143–1269) | 728 (200–2215) | <0.0001 |

| Cystatin, mg/L | 0.77 (0.65–0.90) | 0.81 (0.65–0.97) | 0.84 (0.69–1.05) | 0.87 (0.69–1.11) | <0.0001 |

| GDF‐15 | 1214 (960.8–1601) | 1447 (1126–1918) | 1638 (1220–2263) | 2026 (1465–2996) | <0.0001 |

| Hs‐CRP, mg/L | 2.6 (1.3–6.0) | 3.2 (1.4–6.9) | 3.9 (1.6–10.0) | 5.1 (2.1–16.0) | <0.0001 |

Data are given as median (quartile 1–quartile 3) or number (percentage). ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; GDF‐15, growth differentiation factor‐15; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; hs‐TnT, high‐sensitivity troponin T; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and TIA, transient ischemic attack.

P values from the χ2 test (categorical variables) or the Kruskal‐Wallis test (continuous variables).

Table 2.

Strongest Predictors of Osteoprotegerin Levels at Baseline and 1 Month

| Background Characteristic | Baseline | 1 Month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P Value | N | P Value | |||

| Ticagrelor | 1509 | 0.999 (0.978–1.021) | 0.9536 | |||

| Age, 10‐y increase | 4406 | 1.096 (1.081–1.111) | <0.0001 | 3035 | 1.102 (1.087–1.116) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 1319 | 1.088 (1.059–1.117) | <0.0001 | 894 | 1.072 (1.045–1.100) | <0.0001 |

| STE‐ACS | 2052 | 1.104 (1.075–1.134) | <0.0001 | 1471 | 0.972 (0.948–0.996) | 0.0236 |

| Hs‐TnT, 10% increase | 4406 | 1.002 (1.001–1.002) | <0.0001 | 3035 | 1.000 (0.998–1.002) | 0.9237 |

| GDF‐15, 10% increase | 4406 | 1.023 (1.020–1.026) | <0.0001 | 3035 | 1.013 (1.010–1.016) | <0.0001 |

| Cystatin‐C, 10% increase | 4406 | 0.991 (0.987–0.995) | <0.0001 | 3035 | 1.003 (0.999–1.008) | 0.1612 |

| Hs‐CRP, 10% increase | 4406 | 1.004 (1.003–1.005) | <0.0001 | 3035 | 1.003 (1.002–1.004) | <0.0001 |

| WBC count, 10% increase | 4406 | 1.011 (1.007–1.015) | <0.0001 | 3035 | 1.007 (1.002–1.011) | 0.0022 |

GDF‐15 indicates growth differentiation factor‐15; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; hs‐TnT, high‐sensitivity troponin T; STE‐ACS, ST‐segment–elevation acute coronary syndrome; and WBC, white blood cell.

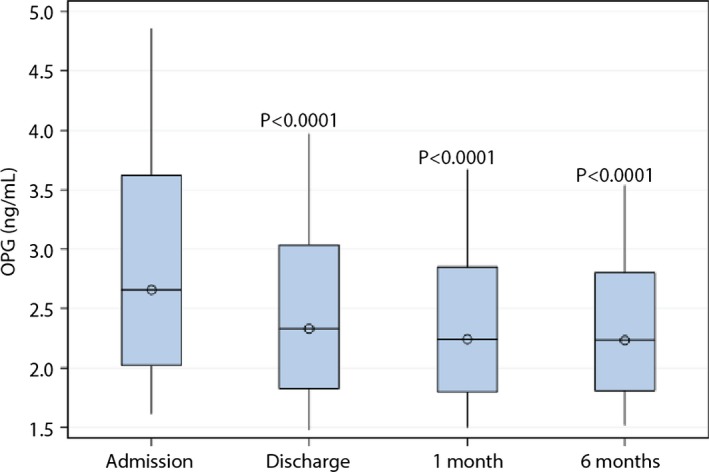

Osteoprotegerin Concentrations During Follow‐Up

In patients with a baseline osteoprotegerin concentration and at least 1 follow‐up sample (N=4679), the median (IQR) concentration was 2.65 (2.02–3.62) ng/mL at baseline. Figure 1 shows osteoprotegerin levels during 6 months of follow‐up. No blood samples were obtained beyond 6 months of follow‐up. Osteoprotegerin decreased significantly at hospital discharge (median [IQR], 2.33 [1.83–3.03] ng/mL; P<0.0001 versus baseline; n=4563) and further at 1 month (median [IQR], 2.24 [1.80–2.85] ng/mL; P<0.0001 versus baseline; n=4237), with a similar level at 6 months (median [IQR], 2.23 [1.81–2.80] ng/mL; P<0.0001 versus baseline; n=3084). No effects of randomized treatment were seen on osteoprotegerin levels at any time point (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Box plots of osteoprotegerin levels on hospital admission and during follow‐up.

Table 3.

Effect of Randomized Treatment on Mean Osteoprotegerin Levels at Discharge and at 1 and 6 Months After Randomization

| Visit | Treatment | na | Mean (SD) | Geometric Meanb | Ratio of Geometric Means (95% CI) | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge | Ticagrelor | 2263 | 2.62 (1.24) | 2.39 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.5958 |

| Clopidogrel | 2300 | 2.56 (1.15) | 2.38 | |||

| Month 1 | Ticagrelor | 2103 | 2.46 (0.98) | 2.28 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.2507 |

| Clopidogrel | 2134 | 2.43 (0.91) | 2.30 | |||

| Month 6 | Ticagrelor | 1513 | 2.46 (0.94) | 2.30 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.1730 |

| Clopidogrel | 1571 | 2.39 (0.91) | 2.26 |

CI indicates confidence interval.

n includes patients with osteoprotegerin samples available at both baseline and the respective visit.

The geometric means are calculated using the antilogarithms of the model‐adjusted means of the logarithm‐transformed data.

P values from an ANCOVA model with the natural logarithm of osteoprotegerin as the outcome variable and logarithm baseline osteoprotegerin and randomized treatment (ticagrelor or clopidogrel) as independent variables.

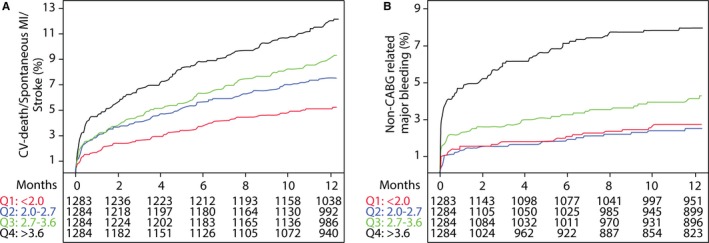

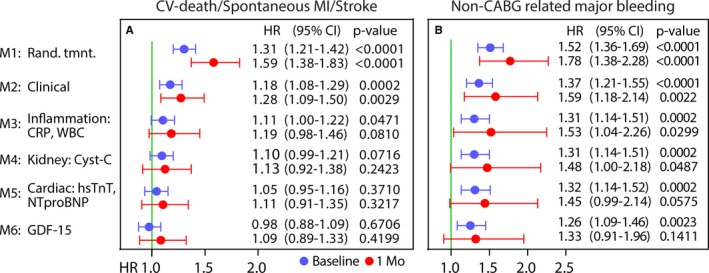

Osteoprotegerin and Cardiovascular Outcomes

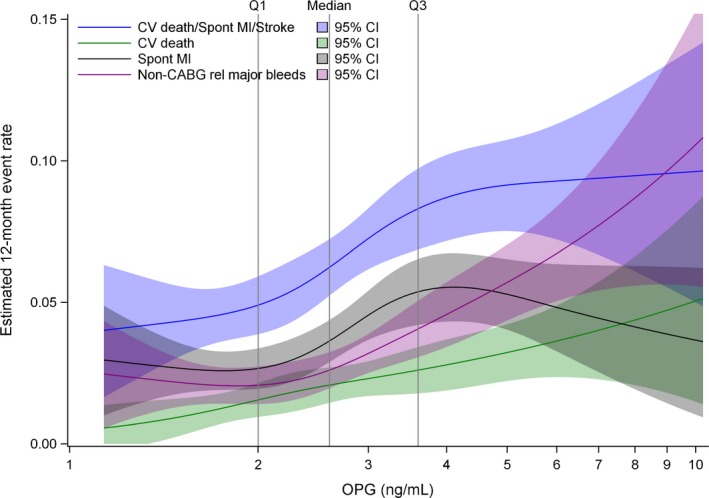

During a predefined follow‐up of 1 year (median, 9 months), the primary end point was observed in 434 patients (8.5%; 193 cardiovascular fatalities, 241 spontaneous MIs, and 62 stroke events). Restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a relatively linear association between high osteoprotegerin levels at baseline and incidence of the primary end point (Figure 2). Kaplan‐Meier analysis (Figure 3A) revealed increasing event rates for the composite end point by quartiles of baseline osteoprotegerin: 5.2%, 7.5%, 9.2%, and 11.9% for quartiles 1 to 4, respectively. As shown in Figure 4A, the unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), per 50% increase in baseline osteoprotegerin concentration, was 1.31 (1.21–1.42). The association remained significant after adjustment for clinical characteristics and biomarkers of inflammation (ie, hs‐CRP and WBC count). However, after full multivariable adjustment, including the cardiac biomarkers and GDF‐15, the HR (95% CI) was 0.98 (0.88–1.09). The HR for cardiovascular death alone was strongly attenuated and not significant after the addition of hs‐CRP and WBC count. Admission osteoprotegerin levels were not associated with risk of stroke, whereas the association with spontaneous MI was not significant after adjustment for clinical characteristics (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Restricted cubic splines for osteoprotegerin in all patients at baseline on the investigated outcomes. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; and MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 3.

Kaplan‐Meier estimated event rates of the primary outcome (composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous myocardial infarction [MI], and stroke; A) and non–coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)‐related major bleeding (B) by quartiles of osteoprotegerin. OPG indicates osteoprotegerin.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) per 50% increase in osteoprotegerin concentration on the primary composite end point (A) and the secondary end point of non–coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) major bleeding (B) during up to 1 year of follow‐up. HRs are presented per 50% increase in biomarker level and are presented after incremental addition of covariates, as detailed left of A and in Statistical Analysis. Point estimates in blue indicate baseline levels, whereas red indicates 1‐month samples. CRP indicates C‐reactive protein; CV, cardiovascular; GDF‐15, growth differentiation factor‐15; hs‐TnT, high‐sensitivity troponin T; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; and WBC, white blood cell.

Table 4.

Associations Between Continuous (HRs per 50% Increase in Osteoprotegerin) or Quartiles of Osteoprotegerin at Baseline (n=5135) and 1 Month (n=4233) and Outcome

| Model | Time | Cardiovascular Death | MI | Stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| 1 | Baseline | 1.47 (1.31–1.64) | <0.0001 | 1.19 (1.07–1.33) | 0.0019 | 1.21 (0.98–1.50) | 0.0773 |

| 1 Mo | 1.87 (1.48–2.35) | <0.0001 | 1.50 (1.25–1.78) | <0.0001 | 1.76 (1.23–2.51) | 0.0019 | |

| 2 | Baseline | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) | 0.0007 | 1.11 (0.98–1.25) | 0.1054 | 1.10 (0.86–1.39) | 0.4460 |

| 1 Mo | 1.30 (0.99–1.70) | 0.0603 | 1.22 (1.00–1.50) | 0.0517 | 1.55 (1.02–2.34) | 0.0384 | |

| 3 | Baseline | 1.05 (0.92–1.22) | 0.4604 | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | 0.2037 | 1.09 (0.83–1.43) | 0.5330 |

| 1 Mo | 1.05 (0.74–1.50) | 0.7886 | 1.20 (0.94–1.53) | 0.1399 | 1.25 (0.74–2.12) | 0.4047 | |

| 4 | Baseline | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 0.6005 | 1.09 (0.95–1.25) | 0.2382 | 1.08 (0.82–1.41) | 0.5947 |

| 1 Mo | 0.90 (0.63–1.27) | 0.5414 | 1.16 (0.91–1.49) | 0.2255 | 1.22 (0.72–2.08) | 0.4567 | |

| 5 | Baseline | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) | 0.7054 | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 0.5700 | 1.09 (0.83–1.43) | 0.5484 |

| 1 Mo | 0.88 (0.63–1.24) | 0.4753 | 1.14 (0.90–1.46) | 0.2835 | 1.22 (0.72–2.08) | 0.4567 | |

| 6 | Baseline | 0.90 (0.78–1.05) | 0.1853 | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) | 0.9088 | 1.16 (0.68–1.98) | 0.5785 |

| 1 Mo | 0.89 (0.64–1.25) | 0.5092 | 1.14 (0.89–1.46) | 0.2995 | 1.49 (0.96–2.29) | 0.0722 | |

CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; and MI, myocardial infarction. Models are described in the Statistical Analysis section in the Methods.

Osteoprotegerin and Major Bleeding

During follow‐up, 200 patients had at least 1 non–CABG‐related major bleeding event. Cubic spline analysis indicated an increase in risk of non–CABG‐related major bleeding from the third quartile (>2.7 ng/mL) of osteoprotegerin at admission (Figure 2). As shown in the Kaplan‐Meier graph (Figure 3B), a particularly high risk of bleeding was found among patients in the top quartile group of osteoprotegerin (>3.6 ng/mL), with an HR (95% CI) of 3.19 (2.12–4.79) versus the lowest quartile. When analyzed as a continuous variable (Figure 4B), there was a 1.52‐fold (95% CI, 1.36–1.69) higher risk of bleeding per 50% increase in baseline osteoprotegerin, which also remained significant after full multivariable adjustment: HR, 1.26 (95% CI, 1.09–1.46). When added to the full multivariable model, osteoprotegerin contributed to discrimination about non–CABG‐related major bleeding (C‐index, 0.70 versus 0.71; P=0.0024 from the likelihood ratio test).

There was also a significant association between osteoprotegerin and non–procedure‐related major bleeding in the fully adjusted model (n=99; HR, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.02–1.50]; P=0.0325). There were no interactions between osteoprotegerin levels and outcomes by randomized treatment or by other tested subgroups, including type of ACS (STE or non‐STE ACS), diabetes mellitus, age, or sex.

Osteoprotegerin Concentrations and Outcomes at 1 Month

Osteoprotegerin levels at 1 month were associated with the occurrence of the primary composite end point after 1 month (n=240), with an HR (95% CI) of 1.59 (1.38–1.83). After adjusting for inflammatory markers, the association between osteoprotegerin at 1 month and the composite end point was not significant: HR (95% CI), 1.19 (0.98–1.66) (Figure 4A). The number of non–CABG‐related major bleeding events after 1 month was low (n=75). Nonetheless, the randomized treatment‐adjusted and fully adjusted HRs (95% CIs) were 1.78 (1.38–2.28) and 1.33 (0.91–1.96), respectively, per 50% increase in osteoprotegerin at 1 month (n=47) (Figure 4B). The number of nonprocedural major bleeding events after 1 month was 58. This limited further statistical analyses.

Discussion

In patients with ACS treated with dual antiplatelet treatment, the osteoprotegerin concentration was independently associated with increased risk of bleeding after adjustment for clinical risk factors and multiple biomarkers prognostic for both cardiovascular events and bleeding. In contrast, although there were independent associations between the osteoprotegerin level on admission and after 1 month and the primary composite cardiovascular end point of cardiovascular death, spontaneous MI, or stroke after adjustment for clinical characteristics and biomarkers of inflammation, these were not sustained after complete adjustment for biomarkers of cardiac function and GDF‐15.

This study, for the first time in patients with ACS, showed that increasing levels of osteoprotegerin were associated with bleeding complications during antiplatelet treatment. The magnitude of the association between osteoprotegerin at admission and bleeding was only marginally affected by the addition of any biomarker and significantly improved the performance of the multivariable model, indicating that the role of osteoprotegerin on bleeding outcomes may be exerted via pathways not reflected by other biomarkers. The final addition of novel biomarker GDF‐15 was crucial because this marker has a proven strong association with bleeding outcomes.8 A low circulating level of the endothelial activation marker vWF is a risk factor for bleeding.25 Osteoprotegerin binds vWF with high affinity, and this complex is present in vivo and may influence bleeding risk.2, 3 In addition, osteoprotegerin may bind vWF reductase, thrombospondin‐1, and in late stages of thrombus formation, this interaction may promote proteolysis of vWF multimers and prevent platelet aggregation.2 This may be beneficial in limiting further plaque progression; however, it could also promote bleeding. Finally, osteoprotegerin is a modulator of vascular calcification and is correlated with coronary calcium scores in the general populations26 and in patients with coronary artery disease.27 Because the degree of coronary calcification is a risk factor for non–CABG‐related major bleeding in ACS,28 it is conceivable that the association between osteoprotegerin and bleeding risk in our study could reflect effects of calcified arteries on bleeding. Such interactions between osteoprotegerin, hemostasis, and calcification warrant further exploration. The serial analyses of osteoprotegerin revealed a decrease in median levels that stabilized at the 1‐month follow‐up. The effect of osteoprotegerin on bleeding and the univariate association with ischemic end points and mortality all exhibited numerically greater point estimates at 1 month. However, the number of events, especially bleeding events, rapidly decreases after the first month of the follow‐up, and this is reflected by the large CIs at 1 month. Thus, although the association with bleeding was not significant in the fully adjusted model at 1 month, our data support that osteoprotegerin may be a novel and stable marker for major bleeding in the setting of ACS and antithrombotic therapy. However, we are unable to draw any conclusions on a possible causative role of osteoprotegerin on ischemic events or bleeding in patients with ACS receiving antithrombotic therapy. Furthermore, it would also be of interest in forthcoming studies to evaluate if osteoprotegerin could be a bleeding biomarker in patients not taking dual antiplatelet therapy or aspirin monotherapy.

Several biomarkers, on admission for ACS, provide clinically important information on risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, including NT‐proBNP (myocardial dysfunction),9, 10 cardiac troponins (myocardial necrosis),29 and cystatin C (kidney function).7, 11 Circulating osteoprotegerin has been reported to be associated with cardiovascular outcomes, including mortality, MI, and incident heart failure, in several ACS cohorts.16, 17, 18, 19 However, although most of these studies include natriuretic peptides,16, 17, 19 troponins,16, 17, 18 and CRP16, 17, 18 in their adjustment strategy, none include GDF‐15, which increases in response to myocardial stress associated with inflammation and tissue damage30 and is becoming a recognized biomarker in ACS.9, 10, 14 In this large study population, the association between high osteoprotegerin levels at admission and risk of the primary end point or cardiovascular death was markedly attenuated and no longer significant after addition of NT‐proBNP, hs‐TnT, and GDF‐15 to the model that included clinical variables and inflammatory biomarkers. This finding suggested that osteoprotegerin in the short‐term phase could reflect a local or systemic inflammatory response to myocardial necrosis, but could not independently predict prognosis. Osteoprotegerin is strongly expressed within the failing myocardium,5 correlates with infarct size after ACS,31 and was strongly associated with cardiac troponin levels in the short‐term phase in our study. Thus, a strong influence of the short‐term phase reaction could attenuate the association with adverse ischemic events, as is seen for CRP.32 At 1 month, hs‐CRP and, in particular, GDF‐15 were among the strongest predictors of osteoprotegerin; they are more closely related to adverse cardiovascular outcomes in our cohort and could, therefore, partly explain the lack of association with outcomes, compared with other studies that lack GDF‐15 measurements. Differences compared with our previous report in 897 patients with ACS, in whom an association between high osteoprotegerin levels at admission and all‐cause mortality was observed, could also be attributable to the markedly longer follow‐up time (89 months) and, thus, a larger proportion and incidence of fatalities.17 Nonetheless, similar to the present study, the relationship between osteoprotegerin and MI was not significant in adjusted analysis.17 Also, in a study by Roysland et al, who evaluated osteoprotegerin in 4463 patients with non‐STE ACS with a similar follow‐up as our study,16 the association with MI was not present in adjusted analysis, although an association with cardiovascular death persisted in adjusted analysis.

Limitations

The current study provides insights to the role of osteoprotegerin in a population with ACS, but it has some limitations. The PLATO trial comprises a broad population with ACS. However, patients requiring dialysis or with recent significant bleeding were not eligible. Furthermore, because mortality was lower in the group randomized to ticagrelor, a survival bias with ticagrelor may have been present. This is important because ticagrelor is known to have bleeding as an adverse effect. Also, the number of bleeding events was not sufficient for subgroup analysis, evaluating the association between osteoprotegerin levels and different types of bleeding. Finally, although we evaluated interactions between osteoprotegerin levels and outcomes by several subgroups (eg, diabetes mellitus status and type of ACS), increased osteoprotegerin levels have been observed in a wide range of diseases and comorbidities,23, 33 also associated with adverse outcome (eg, aortic stenosis33). Because we were unable to account for these diseases and comorbidities, we cannot exclude that they would influence our results. However, our cohort is a representative population with ACS (ie, no inclusion/exclusion criteria to expect any particular selection).

Conclusion

In patients with ACS treated with dual antiplatelet therapy, we observed an independent association between osteoprotegerin concentrations and the risk of major bleeding both at baseline and after 1 month. Osteoprotegerin levels were also associated with ischemic cardiovascular outcomes, even when adjusting for clinical characteristics and biomarkers of inflammation and kidney function (but not for cardiac biomarkers and GDF‐15). High osteoprotegerin levels may be useful in increasing awareness of increased bleeding risk in patients with ACS receiving antithrombotic therapy.

Sources of Funding

The PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial was funded by AstraZeneca. Support for the analyses, interpretation of results, and preparation of the manuscript was provided through funds to the Uppsala Clinical Research Center as part of the Clinical Study Agreement, and provided by a grant from the Swedish Strategic Research Foundation. Roche Diagnostics (Rotkreuz, Switzerland) supported the research by providing the growth differentiation factor‐15 assay free of charge. The authors are entirely responsible for the design and conduct of this study: all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the article, and its final contents.

Disclosures

Åkerblom received an institutional research grant and speaker's fee from AstraZeneca and an institutional research grant from Roche Diagnostics. Ghukasyan and Bertilsson received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca. Becker is a scientific advisory board member for Janssen, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and AstraZeneca and is a member of the safety review committee for Portola. Himmelmann is an employee of AstraZeneca. James received an institutional research grant, honoraria, and a consultant/advisory board fee from AstraZeneca; an institutional research grant and consultant/advisory board fee from Medtronic; an institutional research grant and honoraria from The Medicines Company; and consultant/advisory board fees from Janssen and Bayer. Siegbahn received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline. Storey received institutional research grants, consultancy fees, and honoraria from AstraZeneca; institutional research grants and consultancy fees from PlaqueTec; and consultancy fees from Aspen, Avacta, Bayer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Novartis, The Medicines Company, and ThermoFisher Scientific. Kontny received consultancy fees/honoraria for lectures, advisory board membership, and a fee for research work outside the submitted from AstraZeneca; and advisory board membership and consultancy fees from Merck & Co. Wallentin received institutional research grants, consultancy fees, lecture fees, and travel support from Bristol‐Myers Squibb/Pfizer, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Boehringer Ingelheim; received institutional research grants from Merck & Co and Roche Diagnostics; received consultancy fees from Abbott; and holds 2 patents involving growth differentiation factor‐15. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. PLATO Study Members.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Emma Sandberg and Susanna Thörnqvist (Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala, Sweden).

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007009 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007009.)29330256

References

- 1. Boyce BF, Xing L. Biology of RANK, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(suppl 1):S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zannettino AC, Holding CA, Diamond P, Atkins GJ, Kostakis P, Farrugia A, Gamble J, To LB, Findlay DM, Haynes DR. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is localized to the Weibel‐Palade bodies of human vascular endothelial cells and is physically associated with von Willebrand factor. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:714–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chollet ME, Brouland JP, Bal dit Sollier C, Bauduer F, Drouet L, Bellucci S. Evidence of a colocalisation of osteoprotegerin (OPG) with von Willebrand factor (VWF) in platelets and megakaryocytes alpha granules:studies from normal and grey platelets. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:805–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kees M, Wiesbauer F, Gisslinger B, Wagner R, Shehata M, Gisslinger H. Elevated plasma osteoprotegerin levels are associated with venous thrombosis and bleeding in patients with polycythemia vera. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ueland T, Yndestad A, Oie E, Florholmen G, Halvorsen B, Froland SS, Simonsen S, Christensen G, Gullestad L, Aukrust P. Dysregulated osteoprotegerin/RANK ligand/RANK axis in clinical and experimental heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:2461–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sandberg WJ, Yndestad A, Oie E, Smith C, Ueland T, Ovchinnikova O, Robertson AK, Muller F, Semb AG, Scholz H, Andreassen AK, Gullestad L, Damas JK, Froland SS, Hansson GK, Halvorsen B, Aukrust P. Enhanced T‐cell expression of RANK ligand in acute coronary syndrome: possible role in plaque destabilization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Akerblom A, Wallentin L, Siegbahn A, Becker RC, Budaj A, Buck K, Giannitsis E, Horrow J, Husted S, Katus HA, Steg PG, Storey RF, Asenblad N, James SK. Cystatin C and estimated glomerular filtration rate as predictors for adverse outcome in patients with ST‐elevation and non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes study. Clin Chem. 2012;58:190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hagstrom E, James SK, Bertilsson M, Becker RC, Himmelmann A, Husted S, Katus HA, Steg PG, Storey RF, Siegbahn A, Wallentin L; PLATO Investigators . Growth differentiation factor‐15 level predicts major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the PLATO study. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1325–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wallentin L, Lindholm D, Siegbahn A, Wernroth L, Becker RC, Cannon CP, Cornel JH, Himmelmann A, Giannitsis E, Harrington RA, Held C, Husted S, Katus HA, Mahaffey KW, Steg PG, Storey RF, James SK; PLATO Study Group . Biomarkers in relation to the effects of ticagrelor in comparison with clopidogrel in non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome patients managed with or without in‐hospital revascularization: a substudy from the Prospective Randomized Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation. 2014;129:293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Velders MA, Wallentin L, Becker RC, van Boven AJ, Himmelmann A, Husted S, Katus HA, Lindholm D, Morais J, Siegbahn A, Storey RF, Wernroth L, James SK; PLATO Investigators . Biomarkers for risk stratification of patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes trial. Am Heart J. 2015;169:879–889.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Windhausen F, Hirsch A, Fischer J, van der Zee PM, Sanders GT, van Straalen JP, Cornel JH, Tijssen JG, Verheugt FW, de Winter RJ; Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable Coronary Syndromes (ICTUS) Investigators . Cystatin C for enhancement of risk stratification in non‐ST elevation acute coronary syndrome patients with an increased troponin T. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1118–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mueller C. Biomarkers and acute coronary syndromes: an update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aspromonte N, Di Fusco SA, Latini R, Cruz DN, Masson S, Tubaro M, Palazzuoli A. Natriuretic peptides in acute chest pain and acute coronary syndrome: from pathophysiology to clinical and prognostic applications. Coron Artery Dis. 2013;24:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wollert KC, Kempf T, Lagerqvist B, Lindahl B, Olofsson S, Allhoff T, Peter T, Siegbahn A, Venge P, Drexler H, Wallentin L. Growth differentiation factor 15 for risk stratification and selection of an invasive treatment strategy in non ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:1540–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferraro S, Marano G, Biganzoli EM, Boracchi P, Bongo AS. Prognostic value of cystatin C in acute coronary syndromes: enhancer of atherosclerosis and promising therapeutic target. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:1397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roysland R, Bonaca MP, Omland T, Sabatine M, Murphy SA, Scirica BM, Bjerre M, Flyvbjerg A, Braunwald E, Morrow DA. Osteoprotegerin and cardiovascular mortality in patients with non‐ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2012;98:786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Omland T, Ueland T, Jansson AM, Persson A, Karlsson T, Smith C, Herlitz J, Aukrust P, Hartford M, Caidahl K. Circulating osteoprotegerin levels and long‐term prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pedersen S, Mogelvang R, Bjerre M, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Galatius S, Sorensen TB, Iversen A, Hvelplund A, Jensen JS. Osteoprotegerin predicts long‐term outcome in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiology. 2012;123:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ueland T, Jemtland R, Godang K, Kjekshus J, Hognestad A, Omland T, Squire IB, Gullestad L, Bollerslev J, Dickstein K, Aukrust P. Prognostic value of osteoprotegerin in heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1970–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. James S, Akerblom A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Husted S, Katus H, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington R, Becker R, Wallentin L. Comparison of ticagrelor, the first reversible oral P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J. 2009;157:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Freij A, Thorsen M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BR, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Gabriel Steg P, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasche P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ueland T, Bollerslev J, Godang K, Muller F, Froland SS, Aukrust P. Increased serum osteoprotegerin in disorders characterized by persistent immune activation or glucocorticoid excess: possible role in bone homeostasis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:685–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Model‐checking techniques based on cumulative residuals. Biometrics. 2002;58:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lazzari MA, Sanchez‐Luceros A, Woods AI, Alberto MF, Meschengieser SS. Von Willebrand factor (VWF) as a risk factor for bleeding and thrombosis. Hematology. 2012;17(suppl 1):S150–S152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abedin M, Omland T, Ueland T, Khera A, Aukrust P, Murphy SA, Jain T, Gruntmanis U, McGuire DK, de Lemos JA. Relation of osteoprotegerin to coronary calcium and aortic plaque (from the Dallas Heart Study). Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tousoulis D, Siasos G, Maniatis K, Oikonomou E, Vlasis K, Papavassiliou AG, Stefanadis C. Novel biomarkers assessing the calcium deposition in coronary artery disease. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:901–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Genereux P, Madhavan MV, Mintz GS, Maehara A, Kirtane AJ, Palmerini T, Tarigopula M, McAndrew T, Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Brener SJ, Stone GW. Relation between coronary calcium and major bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndromes (from the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy and Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trials). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:930–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hamm CW, Ravkilde J, Gerhardt W, Jorgensen P, Peheim E, Ljungdahl L, Goldmann B, Katus HA. The prognostic value of serum troponin T in unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kempf T, Eden M, Strelau J, Naguib M, Willenbockel C, Tongers J, Heineke J, Kotlarz D, Xu J, Molkentin JD, Niessen HW, Drexler H, Wollert KC. The transforming growth factor‐beta superfamily member growth‐differentiation factor‐15 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2006;98:351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andersen GO, Knudsen EC, Aukrust P, Yndestad A, Oie E, Muller C, Seljeflot I, Ueland T. Elevated serum osteoprotegerin levels measured early after acute ST‐elevation myocardial infarction predict final infarct size. Heart. 2011;97:460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zebrack JS, Anderson JL, Maycock CA, Horne BD, Bair TL, Muhlestein JB; Intermountain Heart Collaborative (IHC) Study Group . Usefulness of high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein in predicting long‐term risk of death or acute myocardial infarction in patients with unstable or stable angina pectoris or acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ueland T, Aukrust P, Dahl CP, Husebye T, Solberg OG, Tonnessen T, Aakhus S, Gullestad L. Osteoprotegerin levels predict mortality in patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis. J Intern Med. 2011;270:452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. PLATO Study Members.