While a novel regimen for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis has the potential to dramatically improve outcomes, it is imperative to couple recommendations for any novel antimicrobial regimen with corresponding guidance on drug susceptibility testing. We propose a specific, scientifically principled path forward.

Keywords: tuberculosis, drug resistance, microbial, microbial sensitivity tests

Abstract

A novel, shorter-course regimen for treating multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis was recently recommended by the World Health Organization. However, the most appropriate use of drug susceptibility testing (DST) to support this regimen is less clear. Implementing countries must therefore often choose between using a standardized regimen despite high levels of underlying drug resistance or require more stringent DST prior to treatment initiation. The former carries a high likelihood of exposing patients to de facto monotherapy with a critical drug class (fluoroquinolones), whereas the latter could exclude large groups of patients from their most effective treatment option. We discuss the implications of this dilemma and argue for an approach that will integrate DST into the delivery of any novel antimicrobial regimen, without excessively stringent requirements. Such guidance could make the novel MDR tuberculosis regimen available to most patients while reducing the risk of generating additional drug resistance.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Furin and Cox on pages 1212–3.)

In May 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended a novel regimen to treat multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis, shortening the treatment duration from 20 months or more to 9–11 months and cutting treatment costs dramatically [1]. This recommendation was based on preliminary evidence that suggests that up to 90% of patients with MDR tuberculosis could be successfully treated or cured [2–5] and is now being considered for national scale-up in countries from South Africa to India. This landmark recommendation heralds an era in which people with MDR tuberculosis may be cured in less than 1 year, for the first time in history [6]. Remarkably, this recommendation was made at least 2 years before publication of the first randomized trial of this regimen [7, 8], partially reflecting the abysmal standard of care. The current MDR tuberculosis regimen was never tested in a randomized fashion and cures only half of patients placed on treatment [9, 10]. However, as recently discussed [11–14], the implementation of this regimen poses a unique challenge to both the scientific community and country-level officials. Specifically, the capacity for drug susceptibility testing (DST) is exceedingly limited, and despite high levels of background resistance, many of the drugs in the new regimen do not have reliable DST methods established. As such, using this new regimen may result in more patients receiving small numbers of effective drugs, thereby spawning additional resistance. This situation raises a broader question: how should we weigh the potential future harm of irreversible drug resistance against improved treatment for large numbers of patients today—and can general guidance be developed that helps to optimize this balance?

THE NOVEL MULTIDRUG-RESISTANT TUBERCULOSIS REGIMEN: A CLOSER LOOK

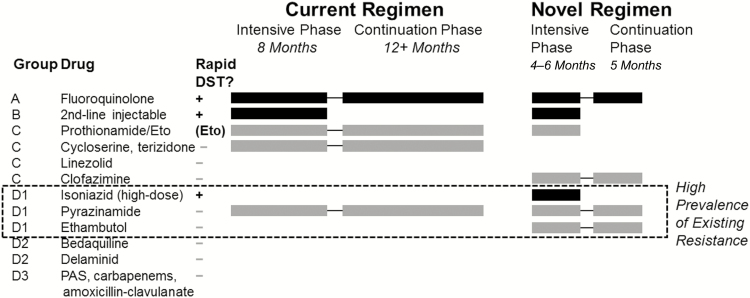

The newly recommended treatment regimen for MDR tuberculosis consists of 7 drugs, of which 3 (isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide [PZA]) are also used for first-line therapy, 2 (a fluoroquinolone and a second-line injectable) represent the most potent second-line drug classes, 1 (prothionamide or ethionamide) is a component of many current second-line regimens, and 1 (clofazimine) is an anti-leprosy agent that has more recently been rediscovered for treatment of tuberculosis (Figure 1). Of these, only 4 agents (fluoroquinolone, clofazimine, PZA, and ethambutol) are continued during the final 5 months of therapy (“continuation phase”). Concomitant with the recommendation to implement this regimen, the WHO also recommended a molecular assay for second-line DST; this is an assay that assesses resistance specifically to fluoroquinolones and second-line injectables [15]. If this is the only second-line DST performed before starting therapy for MDR tuberculosis, the intensive phase would include only 2 drugs with documented susceptibility and the continuation phase would include only 1. This raises the possibility that patients could be exposed for 5 months to a single effective drug, the fluoroquinolone. This drug represents a critical drug class to which Mycobacterium tuberculosis becomes universally resistant in mice after 8 weeks of monotherapy [16], to which 15% of clinical isolates were resistant after patients received multiple single-drug prescriptions [17], and which forms the backbone not only of most MDR tuberculosis regimens but also of many novel first-line regimens under evaluation [18].

Figure 1.

Makeup of typical regimens for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The current regimen consists of at least 5 presumed-effective agents during the 8-month intensive phase (thus often requiring more drugs than depicted here), with removal of the second-line injectable agent during the continuation phase. The novel regimen consists of 1 drug each from groups A and B and 2 from group C during a 4- to 6-month intensive phase. If 4 core drugs cannot be used, drugs from groups D2 (preferred) or D3 should be selected. During the continuation phase (months 5–9) of the novel regimen, the fluoroquinolone (group A) is given only alongside 2 first-line agents and clofazimine. Black bars denote drugs for which rapid, high-quality drug susceptibility testing is available; the dashed box denotes first-line agents to which high levels of resistance are expected in multidrug-resistant-tuberculosis. Although an assay for ethionamide resistance is not formally available, resistance can be inferred on the basis of inhA mutations (detected on available genotypic assays for isoniazid resistance). Abbreviations: DST, drug susceptibility testing; Eto, ethionamide; PAS, P-aminosalicylic acid.

What is the probability that patients with MDR tuberculosis would be exposed to de facto fluoroquinolone monotherapy under this regimen? Unfortunately, this risk is substantial. A recent population-based survey of drug-resistance levels in patients with MDR tuberculosis across 5 countries found mutations in the pncA gene (associated with resistance to PZA) in 36%–81% of all rifampin-resistant (ie, likely MDR) strains [19]. Ethambutol resistance is also widespread and difficult to interpret since many isolates have clinically meaningful resistance levels near the critical concentration [20]. While resistance to clofazimine is presumably rare, the ability of this highly lipophilic drug to protect against resistance to other agents remains uncertain [21]. Finally, the sensitivity of the newly recommended second-line DST assay is far from perfect, especially when done directly on paucibacillary specimens [22] such that even susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and second-line injectables cannot be ensured.

DRUG SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING FOR SECOND-LINE ANTI-TUBERCULOSIS AGENTS

Ideally, susceptibility to additional drugs would be confirmed before use of this regimen, but DST for MDR tuberculosis (Table 1) has major limitations that are unlikely to be overcome in the foreseeable future. While phenotypic DST, which relies on culturing the organism in the presence of each drug, can be performed for each of these agents, such testing requires laborious techniques, weeks of time (for M. tuberculosis to grow), higher risks of contamination, and stringent biosafety protections. Furthermore, uncertainty exists about the appropriate critical concentration (and the clinical relevance of resistance at different concentrations) for each drug [23]. As such, if the goal of the shorter-course regimen were to facilitate treatment access for a broader number of patients with MDR tuberculosis, a concomitant requirement for phenotypic DST prior to starting therapy would be counterproductive.

Table 1.

Resistance Patterns and Drug Susceptibility Testing for Typical Agents in the Novel Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Regimen.

| Drug Class (World Health Organization Group) | Intensive Phase? | Continuation Phase? | Typical Prevalence of Resistance (in Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis) | Rapid Molecular DST? | Molecular DST Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolones (A) | Yes | Yes | 0%–10% (moxifloxacin, 2 μg/mLa) | Yes | LPA sensitivity 84% in culture isolates [37] |

| Second-line injectables (B) | Yes | No | 0–10% | Yes | LPA sensitivity ≥95% (kanamycin, direct) [37] |

| Prothionamide/Ethionamide (C) | Yes | No | 5%–20% | (Eto)b | Many mutations confer resistance |

| Clofazimine (C) | Yes | Yes | <5% (presumed) | No | Molecular basis of resistance uncertain |

| Isoniazid (D, high-dose) | Yes | No | 100% (low-dose), 50%–80% (high-level katG mutation) | Yes | LPA sensitivity 91% [38] |

| Pyrazinamide (D) | Yes | Yes | 35%–80% (pncA mutation) | No | Sequencing pncA may have 75%–85% sensitivity [39] |

| Ethambutol (D) | Yes | Yes | 30%–70% | No | Uncertain critical concentration for DST |

Abbreviations: DST, drug susceptibility testing; Eto, ethionamide; LPA, line probe assay.

aResistance to other agents (eg, ofloxacin) or to moxifloxacin at a lower concentration (eg, 0·5 μg/mL) is commonly measured clinically and may be higher than 10% in some settings, especially in Eastern Europe.

bResistance to ethionamide can be inferred from inhA mutations on standard assays for isoniazid resistance.

Unlike phenotypic DST, genotypic DST, which relies on identification and amplification of genetic mutations associated with drug resistance, can be performed within hours using relatively simple laboratory techniques on commercially available platforms and with lower risks of contamination or infectious exposure [24]. As such, genotypic DST, when available, is much more easily performed at scale. Unfortunately, however, genotypic DST for most anti-tuberculosis agents (other than isoniazid, rifampin, fluoroquinolones, and second-line injectables) is challenging. In the case of PZA, the potential genetic mutations associated with resistance number in the hundreds. Though most of these are confined to the 561 base-pair pncA gene and its promoter, many mutations in this gene are not consistently associated with phenotypic resistance, and certain deletions that do confer resistance are not consistently detected [25]. While key specific mutations in the embB gene (encoding resistance to ethambutol) are known, up to 30% of phenotypically resistant strains have no mutations in this gene, and embB mutations can be found in 35% or more of strains without high-level ethambutol resistance [26, 27]. For both of these agents, phenotypic DST itself represents an imperfect gold standard, as it is uncertain which critical concentrations in vitro correspond to clinically relevant resistance in vivo [28]. In the case of clofazimine, even the mechanisms of resistance, much less the corresponding mutations, remain poorly characterized [21]. For clofazimine and most novel agents (eg, bedaquiline, delaminid), there are currently no rapid genotypic DST assays in the diagnostic pipeline.

In summary, phenotypic DST is logistically and scientifically challenging to perform at scale, whereas genotypic DST for drugs in the continuation phase of the novel regimen must address obstacles that are not easily overcome. Furthermore, the majority of patients with MDR tuberculosis may harbor strains that are resistant to ethambutol and PZA, and clofazimine generally does not enter the same compartments with the same penetration as fluoroquinolones [29]. Thus, if the novel short-course MDR regimen is implemented at scale, supported only by the recommended genotypic DST assay (which itself may not be immediately available in many settings), it is likely that a substantial number of patients will be exposed to de facto fluoroquinolone monotherapy, particularly during the continuation phase.

WILL FLUOROQUINOLONES BE LOST?

The clinical effectiveness of single agents against tuberculosis has been well studied. In 1947, the British Medical Research Council undertook arguably the first large-scale, randomized clinical trial of streptomycin as a stand-alone anti-tuberculosis drug [30]. While 51% of patients showed a positive clinical response to streptomycin, M. tuberculosis could be cultured from the sputum of 85% of patients after completing treatment, and most isolates had evidence of streptomycin resistance. Supplemental agents for tuberculosis treatment, including isoniazid and p-aminosalicylic acid, were added only a few years later [31], but major damage was arguably already done. Though streptomycin has not been a major component of first-line tuberculosis therapy for more than 30 years, the prevalence of streptomycin resistance in M. tuberculosis remains 30% or higher in many areas [32]. Using an antimicrobial agent as monotherapy for tuberculosis for even a few years can thus permanently impair that drug’s population-level effectiveness.

Importantly, the situation for fluoroquinolones in the recommended novel regimen is much less dire than for streptomycin. The 7-drug intensive phase, which may be extended to 6 months in patients with prolonged culture positivity, will reduce the number of organisms among which resistance could be selected during the continuation phase; ancillary drugs are likely to have some benefit even when resistance-conferring mutations are present; other newly approved drugs can be added if resistance is suspected; and agents in the novel regimen have sterilizing activity that streptomycin lacks. In the first published observational study of a similar 9-month fluoroquinolone- and clofazimine-based regimen [5], only 11 of 515 patients (2.1%) had persistent or recurrent tuberculosis after 24 months of follow-up. For all of these reasons, it is unlikely that the story of streptomycin will repeat itself entirely with fluoroquinolones. Nevertheless, given the exceedingly poor outcomes seen in patients with MDR tuberculosis whose strains are also resistant to fluoroquinolones [9], we must make every effort to protect this critical class of drugs.

Of particular interest is resistance to PZA, which is the only bactericidal agent other than the fluoroquinolone in the continuation phase of the novel regimen. PZA is critical to the achievement of relapse-free cure of drug-susceptible tuberculosis in 6 months [33] and also features as a component of most experimental shorter-course first-line regimens [31]. PZA demonstrated synergy with fluoroquinolones in mouse studies of tuberculosis drug regimens [34] and, as discussed above, DST for PZA is particularly challenging. In understanding whether using the novel MDR tuberculosis regimen without ability to verify PZA susceptibility could cause emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance, it is therefore critical to understand how the regimen will fare in patients who have MDR tuberculosis with additional resistance to PZA.

Data to inform this important question are scant. In the initial study of a shorter-course MDR tuberculosis regimen [5], DST for PZA was performed in fewer than half of all patients, and PZA resistance was detected in 41% of those tested. The unadjusted odds ratio for unfavorable outcomes, comparing patients with PZA resistance vs without PZA resistance, was 1.7 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.83–3.6). In a stepwise backward elimination model, the odds ratio for unfavorable outcome associated with PZA resistance was 9.2 (95% CI, 1.3–187). Thus, given current data, it is possible that PZA resistance has no clinical importance in patients being treated with the novel regimen – but it is also possible that PZA resistance increases the odds of an unfavorable outcome by a factor of 10.

Importantly, M. tuberculosis can develop resistance to key agents such as fluoroquinolones within weeks, but the timelines on which we can react to emerging resistance span many years. By the time meaningful changes in MDR tuberculosis treatment could be implemented at the policy level, irreversible increments in fluoroquinolone resistance could occur, endangering the effectiveness not just of MDR tuberculosis therapy but of treatment-shortening first-line regimens in development as well. However, if preliminary data on treatment success of the novel MDR tuberculosis regimen are confirmed, withholding this regimen from patients with MDR tuberculosis could mean the loss of tens of thousands of lives every year.

IMPLEMENTERS’ DST DILEMMA

Against this backdrop, implementing countries must decide how to implement DST in conjunction with the new MDR tuberculosis regimen. Exclusion criteria for this regimen in the current WHO guidance include “confirmed resistance or suspected ineffectiveness to a medicine in the shorter MDR-tuberculosis regimen (except isoniazid resistance)” [1]. In most low-income countries that lack large-scale capacity to perform second-line DST, this translates into a choice of expanding laboratory capacity, implementing the regimen without DST (similar to what is often currently done for the standard regimen), or not implementing the regimen at all. On one hand, very good individual-level outcomes have been achieved in existing observational studies without stringent DST [2–5]. On the other hand, evidence already exists that standardized use of the longer, conventional regimen (without second-line DST) is fueling additional second-line drug resistance at the population level [35].

In other settings (eg, South Africa and Brazil), where genotypic DST for fluoroquinolones and second-line injectables is more accessible, full phenotypic DST remains programmatically unavailable. In these countries, if full phenotypic DST were scaled up, half or more of all patients with MDR tuberculosis could be considered ineligible on the basis of resistance to PZA and ethambutol alone. However, if such DST were not performed, the new regimen could presumably be delivered to all patients with MDR tuberculosis without genotypic evidence of fluoroquinolone or second-line injectable resistance. Indeed, WHO guidance is clear that DST for PZA and ethambutol should not impede scale-up of the new regimen [36].

In summary, medium- and high-burden countries are now in the uncomfortable position of either scaling up a novel antimicrobial regimen without the DST knowledge necessary to prevent the likely emergence of resistance or not implementing the regimen at all. Requiring confirmed susceptibility to all agents in a regimen will exclude the vast majority of patients from any treatment because of the logistical and time delays inherent in performing phenotypic DST and the high levels of background resistance to many agents (eg, PZA and ethambutol). More stringent DST requirements will also engender pressure from society and patients to make the regimen more widely available, as patients today stand to benefit greatly from this new regimen. However, less stringent requirements could lead to a self-generated epidemic of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis that could take decades to reverse.

AN URGENT NEED FOR DATA

At this critical juncture, it is essential that the scientific community rapidly weigh in. Policymakers throughout the world require urgent evidence-based insight on the potential trade-offs of treating more people with a life-threatening condition vs protecting key antimicrobial agents for generations to come. Additional empirical data are also essential. We will never know whether to treat people who have MDR tuberculosis plus additional drug resistance (especially resistance to PZA and ethambutol) with this novel regimen if we do not collect high-quality data on the long-term outcomes of such patients. These data should include subgroup analyses of patients with documented PZA or other drug resistance in ongoing randomized trials of shorter-course fluoroquinolone-based regimens for MDR tuberculosis (eg, stage 1 of the STREAM trial, n = 400 patients [7]); pragmatic studies of outcomes in such patients in countries likely to implement the novel MDR tuberculosis regimen at scale (eg, South Africa); and detailed evaluations (eg, serial cultures for M. tuberculosis detection and full DST, with long-term follow-up) in a smaller number of patients with PZA-resistant and PZA-susceptible MDR tuberculosis being treated with the new regimen, in order to detect acquired fluoroquinolone (and other) resistance early and correlate such resistance with clinical outcomes.

The ethical implications of such studies (in which individuals with confirmed additional drug resistance are nonetheless treated with the new MDR tuberculosis regimen) must also be rapidly addressed. We argue that, in the context of close monitoring and capacity to switch regimens accordingly, the societal benefit of understanding treatment outcomes in these patients outweighs any individual-level harm of using this regimen. Indeed, individuals with additional resistance comprise half or more of all participants in prior studies of the novel short-course regimen (in which resistance to these agents was not universally verified).

ADDRESSING THE POLICY GAP

While we await these data, scientists also have a moral obligation to weigh in on appropriate policy recommendations to implementing countries. Our perspective is that setting a precedent of either very limited scale-up or of unbridled implementation of a novel drug regimen could be dangerous and that having data is always superior to operating without an evidence base. We also believe that any policy to treat individuals with drug-resistant disease must include equally weighted recommendations regarding diagnosis of drug resistance. Keeping these principles in mind, we posit the following 2 recommendations for DST to accompany the novel MDR tuberculosis regimen for consideration by the scientific and policy communities:

DST (genotypic or phenotypic) for fluoroquinolones and second-line injectables should be required for all patients at the time of initiating the novel regimen. Although the regimen may be initiated while awaiting DST results, no patient should be continued on the novel regimen for more than 2 months without documented susceptibility to both of these agents.

If monthly cultures cannot be performed as recommended, all patients starting the novel regimen should at least have mycobacterial cultures performed after 2–4 months of (7-drug) therapy, including second-line DST on any positive culture. Before starting the continuation phase, patients must have either documented culture conversion or documented susceptibility to fluoroquinolones plus at least 1 other agent in the regimen (ie, PZA, ethambutol, or another agent that might be carried forward into the continuation phase).

It is important to note that these recommendations are consistent with current WHO guidance (preferring the performance of second-line DST and advocating for monthly cultures) [36]. However, they set a precedent of including a requirement for DST among the highest-level recommendations for any novel treatment regimen, rather than mentioning DST as a conditional suggestion that will often not be followed in practice. We believe that these recommendations would still enable a sufficiently large number of patients with MDR tuberculosis to be treated. In most settings with the capacity to provide second-line therapy, systems can be established to send sputum specimens to a centralized lab for culture and DST. These recommendations are also consistent with general principles of maximizing access to the most potent antimicrobial agents available while also ensuring treatment with multiple effective agents. Finally, adoption of these recommendations would provide strong motivation to develop validated molecular DST assays for PZA and other second-line agents and to collect appropriate data on patient outcomes with additional drug resistance in the initial years following implementation of this new regimen.

CONCLUSION

As we enter a new era of shorter-course treatment for MDR tuberculosis, it is important to set a precedent of not withholding life-saving treatment from patients who desperately need it, while also protecting critical antimicrobial agents for future generations. Achieving this balance requires thoughtful and engaged discussion among the scientific and policy communities. As such, recommendations to treat drug-resistant pathogens must be accompanied by clear recommendations about how to test for drug susceptibility. We have offered one potential solution that would ensure susceptibility to at least 2 antimicrobial agents at all points in the novel treatment regimen, in hopes that this will initiate a broader debate and ultimately result in updated guidance regarding the performance of DST to support this novel regimen.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (work order 10, Modeling Impact for Novel TB Drug Regimens). G. T. acknowledges funding from the Wellcome Trust, a South African Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship, the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership as part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union, and the Royal Society.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis: 2016 update Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Deun A, Maug AK, Salim MA et al. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182:684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kuaban C, Noeske J, Rieder HL, Aït-Khaled N, Abena Foe JL, Trébucq A. High effectiveness of a 12-month regimen for MDR-TB patients in Cameroon. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19:517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piubello A, Harouna SH, Souleymane MB et al. High cure rate with standardised short-course multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in Niger: no relapses. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18:1188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aung KJ, Van Deun A, Declercq E et al. Successful ‘9-month Bangladesh regimen’ for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among over 500 consecutive patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18:1180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2015 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nunn AJ, Rusen ID, Van Deun A et al. Evaluation of a standardized treatment regimen of anti-tuberculosis drugs for patients with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (STREAM): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014; 15:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moodley R, Godec TR; STREAM Trial Team Short-course treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: the STREAM trials. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahuja SD, Ashkin D, Avendano M et al. ; Collaborative Group for Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data in MDR-TB. Multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis treatment regimens and patient outcomes: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 9,153 patients. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zumla A, Abubakar I, Raviglione M et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis—current dilemmas, unanswered questions, challenges, and priority needs. J Infect Dis 2012; 205Suppl 2:S228–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sotgiu G, Tiberi S, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Zumla A, Migliori GB. WHO recommendations on shorter treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet 2016; 387:2486–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varaine F, Guglielmetti L, Huerga H et al. Eligibility for the shorter multidrug-resistant tuberculosis regimen: ambiguities in the World Health Organization recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194:1028–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berry C, Achar J, du Cros P. WHO recommendations for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet 2016; 388:2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sotgiu G, Tiberi S, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Zumla A, Migliori GB. WHO recommendations for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis—authors’ reply. Lancet 2016; 388:2234–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. The use of molecular line-probe assays for the detection of resistance to second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs: policy guidance Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ginsburg AS, Sun R, Calamita H, Scott CP, Bishai WR, Grosset JH. Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis during continuously dosed moxifloxacin monotherapy in a mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:3977–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Long R, Chong H, Hoeppner V et al. Empirical treatment of community-acquired pneumonia and the development of fluoroquinolone-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:1354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wallis RS, Maeurer M, Mwaba P et al. Tuberculosis—advances in development of new drugs, treatment regimens, host-directed therapies, and biomarkers. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:e34–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zignol M, Dean AS, Alikhanova N et al. Population-based resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to pyrazinamide and fluoroquinolones: results from a multicountry surveillance project. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:1185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wright A, Zignol M.. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world: fourth global report: the World Health Organization/International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease global project on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance surveillance, 2002–2007. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Palomino JC, Martin A. Drug Resistance Mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibiotics 2014; 3:317–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tagliani E, Cabibbe AM, Miotto P et al. Diagnostic performance of the new version (v2.0) of GenoType MTBDRsl assay for detection of resistance to fluoroquinolones and second-line injectable drugs: a multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:2961–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim SJ. Drug-susceptibility testing in tuberculosis: methods and reliability of results. Eur Respir J 2005; 25:564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalokhe AS, Shafiq M, Lee JC et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis drug susceptibility and molecular diagnostic testing. Am J Med Sci 2013; 345:143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang Y, Shi W, Zhang W, Mitchison D. Mechanisms of pyrazinamide action and resistance. Microbiol Spectr 2014;2:MGM2-0023-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Deun A, Martin A, Palomino JC. Diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis: reliability and rapidity of detection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010; 14:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng S, Cui Z, Li Y, Hu Z. Diagnostic accuracy of a molecular drug susceptibility testing method for the antituberculosis drug ethambutol: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:2913–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miotto P, Cabibbe AM, Feuerriegel S et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pyrazinamide resistance determinants: a multicenter study. MBio 2014; 5:e01819–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mafukidze A, Harausz E, Furin J. An update on repurposed medications for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2016; 18:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Medical Research Council. A Medical Research Council investigation. Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Br Med J 1948; 2:769–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zumla A, Nahid P, Cole ST. Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013; 12:388–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pablos-Méndez A, Raviglione MC, Laszlo A et al. Global surveillance for antituberculosis-drug resistance, 1994–1997. World Health Organization-International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Working Group on Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:1641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. British Thoracic Association. A controlled trial of six months chemotherapy in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982; 126:460–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ahmad Z, Tyagi S, Minkowski A, Peloquin CA, Grosset JH, Nuermberger EL. Contribution of moxifloxacin or levofloxacin in second-line regimens with or without continuation of pyrazinamide in murine tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Müller B, Chihota VN, Pillay M et al. Programmatically selected multidrug-resistant strains drive the emergence of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. PLoS One 2013; 8:e70919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization. Frequently asked questions about the implementation of the new WHO recommendation on the use of the shorter MDR-TB regimen under programmatic conditions Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/drug-resistant-tb/treatment/FAQshorter_MDR_regimen.pdf. Accessed 10 September 2016.

- 37. Theron G, Peter J, Richardson M et al. The diagnostic accuracy of the GenoType(®) MTBDRsl assay for the detection of resistance to second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 10:CD010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nathavitharana RR, Hillemann D, Schumacher SG et al. Multicenter noninferiority evaluation of hain genotype MTBDRplus version 2 and nipro NTM+MDRTB line probe assays for detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:1624–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maningi NE, Daum LT, Rodriguez JD et al. Improved detection by next-generation sequencing of pyrazinamide resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:3779–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]