Evidence for safety and efficacy of antibacterial prophylaxis in pediatric leukemia is limited. In this study, levofloxacin prophylaxis during induction therapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia reduced other antibiotic exposure and prevented febrile neutropenia, systemic infection, and Clostridium difficile infection.

Keywords: prophylaxis, leukemia, child, levofloxacin, Clostridium difficile

Abstract

Background

Infection is the most important cause of treatment-related morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Although routine in adults with leukemia, antibacterial prophylaxis is controversial in pediatrics because of insufficient evidence for its efficacy or antibiotic choice and concerns about promoting antibiotic resistance and Clostridium difficile infection.

Methods

This was a single-center, observational cohort study of patients with newly diagnosed ALL, comparing prospectively collected infection-related outcomes in patients who received no prophylaxis, levofloxacin prophylaxis, or other prophylaxis during induction therapy on the total XVI study. A propensity score–weighted logistic regression model was used to adjust for confounders.

Results

Of 344 included patients, 173 received no prophylaxis, 69 received levofloxacin prophylaxis, and 102 received other prophylaxis regimens. Patients receiving prophylaxis had longer duration of neutropenia. Prophylaxis reduced the odds of febrile neutropenia, likely bacterial infection, and bloodstream infection by ≥70%. Levofloxacin prophylaxis alone reduced these infections, but it also reduced cephalosporin, aminoglycoside, and vancomycin exposure and reduced the odds of C. difficile infection by >95%. No increase in breakthrough infections with antibiotic-resistant organisms was seen, but this cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

This is the largest study to date of antibacterial prophylaxis during induction therapy for pediatric ALL and the first to include a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone. Prophylaxis prevented febrile neutropenia and systemic infection. Levofloxacin prophylaxis also minimized the use of treatment antibiotics and drastically reduced C. difficile infection. Although long-term antibiotic-resistance monitoring is needed, these data support using targeted prophylaxis with levofloxacin in children undergoing induction chemotherapy for ALL.

Clinical Trials Registration

Infections remain the most frequent cause of serious treatment-related morbidity and mortality in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); currently, up to 4% of children with ALL die of infection [1–4]. Even nonfatal infections can result in permanent end-organ damage, contribute to chemotherapy delay or modification, and increase antibiotic exposure [5]. Most serious infections occur during the relatively short induction phase of chemotherapy [2].

Primary antibacterial prophylaxis during chemotherapy-related neutropenia in adults reduces clinically documented infection, microbiologically documented infection, and infection-related mortality [6]. The US National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends antibacterial prophylaxis with levofloxacin, a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone, for adult patients with acute leukemia. In addition, findings of animal studies suggesting that colonization with Clostridium difficile might be reduced by replacing β-lactam antibiotics with fluoroquinolones [7] are intriguing because hospital-acquired C. difficile infection is associated with a 6.7-fold increase in the odds of mortality in hospitalized children [8]. However, no clinical studies have shown that fluoroquinolone prophylaxis can prevent C. difficile infection in high-risk patients.

In the pediatric ALL population, primary antibacterial prophylaxis is controversial, because data supporting its efficacy and safety are sparse. There are 2 published studies of antibacterial prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones for pediatric ALL. An unadjusted retrospective analysis, from Saudi Arabia, reported reduced bloodstream infection (BSI) and other infections with ciprofloxacin prophylaxis during delayed intensification [9]. However, a randomized controlled trial of ciprofloxacin prophylaxis during induction therapy in Indonesia found a marked increase in the risk of fever, BSI, and death [10]. No published studies to our knowledge conducted in the pediatric population have evaluated the use of broad-spectrum fluoroquinolones (which may have greater efficacy than narrow-spectrum agents such as ciprofloxacin), compared fluoroquinolones with other prophylaxis regimens, or assessed the impact of antibacterial prophylaxis on C. difficile infection. The current study aimed to identify the effects of antibacterial prophylaxis during induction therapy for pediatric ALL on antibiotic exposure, infection, and febrile neutropenia, and on C. difficile infection.

METHODS

This was an observational cohort study of patients receiving induction therapy for newly diagnosed ALL. Infection-related adverse event data were collected prospectively by the study team and evaluated by cross-referencing with the electronic medical record and institutional microbiology and pharmacy databases. Data describing prophylaxis prescribing and antibiotic exposure were collected retrospectively. The study was approved by the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Review Board (XPD04-070).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible for inclusion were all patients enrolled in the total XVI study for newly diagnosed ALL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00549848) at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital from the opening of the trial (29 October 2007) who completed induction therapy before 6 January 2016. Similarly to a previous study, total XV [11], induction therapy was administered over 42 days and comprised 4 weeks of prednisone, 4 doses of weekly vincristine, 2 doses of weekly daunorubicin, and 1 or 2 doses of PEG-asparaginase, followed by 2 weeks of cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, and thioguanine, plus intrathecal chemotherapy according to risk category (Supplementary Table S1). The induction phase could be modified or prolonged in response to infection or other complications. Participants with clinically or microbiologically documented infection before induction therapy initiation or who had fever before induction therapy requiring prolonged antibiotic therapy (>4 days) were excluded from this analysis to avoid misclassification of antibacterial treatment as prophylaxis. Similarly, patients who developed febrile neutropenia or suspected infection during the first 7 days of induction or after <2 days of neutropenia were excluded because there was insufficient opportunity to initiate primary prophylaxis.

Definition of Primary Prophylaxis

Primary prophylaxis was defined as the administration of systemic antibacterial agents during induction therapy, before the first episode of suspected or proven infection or febrile neutropenia, with the intent to prevent infection. Appropriate perioperative or Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis and empiric short courses of antibiotic given for fever at presentation or for clinical events other than infection or febrile neutropenia, such as vomiting, headache, or vertigo, were not considered prophylaxis. From 2007 until July 2014, antibacterial prophylaxis was provided at the discretion of the treating clinician. It typically consisted of cefepime, ciprofloxacin, or vancomycin plus cefepime or ciprofloxacin and was initiated after the first documented neutropenia after chemotherapy. From August 2014, institutional guidelines recommended levofloxacin prophylaxis during all episodes of neutropenia expected to last ≥7 days.

Management of Febrile Neutropenia and Suspected Infection

The recommended febrile neutropenia treatment was cefepime (or ceftazidime plus vancomycin if cefepime was unavailable), with addition of vancomycin or an aminoglycoside for specified indications [12, 13] and substitution of meropenem for cefepime in patients who had recently received cefepime or had suspected intra-abdominal or Bacillus cereus infection [13]. These guidelines did not change during the study period.

Definitions Related to Infection

The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 [14], were used to capture all infection-related adverse events in the study database, and standard definitions were used to further categorize episodes (Table 1). Antibiotic exposure was quantified as “antibiotic days,” “specific antibiotic days,” and “cumulative antibiotic exposure.” Antibiotic days were calculated for each patient as the simple proportion of induction days on which ≥1 systemic antibacterial antibiotic was administered (excluding Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis), and specific antibiotic days were calculated as the proportion of induction days on which a specific antibiotic was administered (cefepime and ceftazidime were combined). Cumulative antibiotic exposure was calculated as the sum of all specific antibiotic days divided by the number of induction days, accounting for the potential additive effect of coadministered antibiotics.

Table 1.

Definitions Related to Infections

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| Neutropenia | Absolute neutrophil count ≤500/μL |

| Profound neutropenia | Absolute neutrophil count ≤100/μL |

| Febrile neutropenia | Core body temperature ≥38.3°C or ≥38.0°C for ≥1 h in context of neutropenia [15, 16] |

| Microbiologically documented infection | Diagnosed bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infection, with supportive microbiological evidence, such as a positive culture, antigen or PCR test results, or characteristic histopathological findings [15] |

| Clinically documented infection | Infection diagnosed by the treating clinician for which a specific microbial cause could not be demonstrated [15] |

| Likely bacterial infection | Any infection with a microbiologically documented bacterial cause or that was clinically documented in categories typically attributed to bacterial infection, including pneumonia, skin and soft-tissue infection, osteomyelitis or myositis, enterocolitis, otitis media or externa, sinusitis, epididymo-orchitis, CVC pocket or tunnel infection, pharyngitis, perianal abscess or cellulitis, peritonitis, lymphadenitis, or culture-negative sepsis |

| Bloodstream infection | Any infection caused by a recognized pathogen that was isolated from ≥1 blood culture in the context of a compatible clinical illness; common commensal bacteria were included if identified from multiple culture sets, or if a single blood culture set was collected before start of antibiotic therapy and the result deemed clinically significant by the treating clinician [17, 18] |

| Severe sepsis | Infection in conjunction with severe dysfunction of cardiovascular or respiratory systems or ≥2 other organ systems [19]; fever or elevated WBC count not required |

| Urgent intervention | Infection requiring admission to the intensive care unit, fluid resuscitation, or supplemental oxygen or associated with clinician diagnosis of septic shock |

| Clostridium difficile infection | Identification of C. difficile toxin in stool by enzyme immunoassay (from 2007 to April 2010) or toxin gene PCR (from April 2010 onward) in the presence of diarrhea |

| Enterocolitis | Syndrome of abdominal pain in conjunction with radiologically documented bowel-wall thickening or microbiologically documented C. difficile infection |

Abbreviations: CVC, central venous catheter; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WBC, white blood cell count.

Statistical Methods

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions, and Kruskal-Wallis or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare medians. Associations between primary antibacterial prophylaxis and clinical outcomes were assessed using multiple logistic regression, and Firth’s penalized likelihood approach was used to address the problem of complete separation [20]. Propensity to receive prophylaxis was estimated with a multinomial logistic regression model including age, sex, race, Down syndrome, and leukemia type as predictors. Then, a logistic regression model was used to model prophylaxis groups and duration of profound neutropenia as predictors, with inverse probability weighting based on the propensity score. Kaplan-Meier estimates of disease-free survival were used to graph the time to first event for infection events in prophylaxis groups and were compared using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute), and differences were considered significant at P < .05 (2 tailed). No power calculation was performed.

RESULTS

Of 505 patients assessed for eligibility, 161 were excluded because of the onset of suspected infection before induction therapy (n = 64), within the first 7 days of induction (n = 41), or after <2 days of neutropenia (n = 19), or because of fever at presentation requiring prolonged treatment (n = 37). Of the remaining 344 patients, 173 received no primary prophylaxis, 69 received levofloxacin prophylaxis, and 102 received other prophylaxis (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). Other prophylaxis regimens comprised cefepime, ciprofloxacin, or vancomycin plus cefepime or ciprofloxacin (Supplementary Table S2). The median durations of neutropenia and profound neutropenia were longer in patients receiving prophylaxis (Table 2), so duration of profound neutropenia was included with propensity score in multivariate analyses. Analyses related to C. difficile infection also included duration of meropenem exposure, because this drug was targeted by antimicrobial stewardship interventions.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Patients With or Without Prophylaxis

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%)a | P Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Prophylaxis (n = 173) | Levofloxacin Prophylaxis (n = 69) | Other Antibiotic Prophylaxis (n = 102) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 5.8 (3 –11.9) | 6.8 (3.9–11.1) | 7 (3.6 –11.9) | .67 |

| Age group | .75 | |||

| ≥10 y | 50 (29) | 18 (26) | 32 (31) | |

| <10 y | 123 (71) | 51 (74) | 70 (69) | |

| Sex | .59 | |||

| Male | 103 (60) | 43 (62) | 56 (55) | |

| Female | 70 (40) | 26 (38) | 46 (45) | |

| Race | .86 | |||

| White | 134 (77) | 56 (81) | 80 (78) | |

| Others | 3 (23) | 13 (19) | 22 (22) | |

| Down syndrome | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | >.99 |

| ALL type | .57 | |||

| T | 29 (17) | 15 (22) | 21 (21) | |

| B | 144 (83) | 54 (78) | 81 (79) | |

| ALL risk category | .14 | |||

| Low | 89 (51) | 37 (54) | 51 (50) | |

| Standard | 81 (47) | 28 (41) | 43 (42) | |

| High | 3 (2) | 4 (6) | 8 (8) | |

| Duration of neutropenia, median (IQR), d | 17 (11–24) | 18 (12–23) | 20 (17–25) | .002 |

| Duration of profound neutropenia, median (range), d | 6 (2–13) | 7 (4–12) | 11 (5–16) | .001 |

Abbreviations. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; IQR, interquartile range.

aData represent No. (%) of patients except where otherwise specified.

bFisher exact test was used for categorical and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

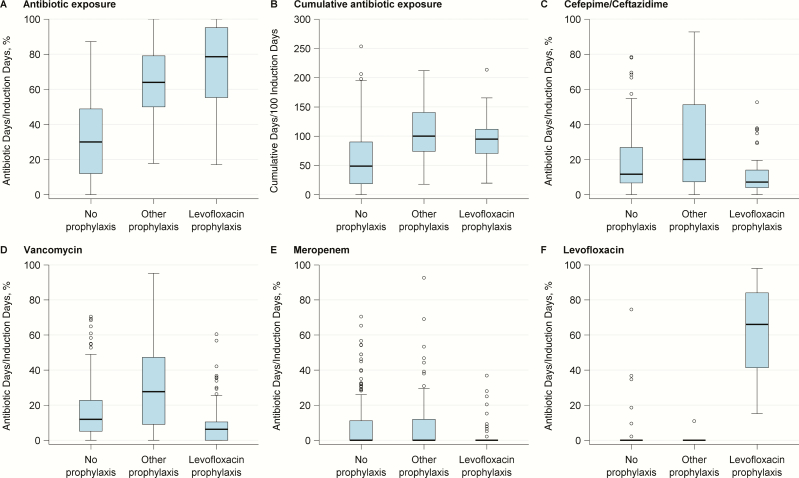

Total antibiotic days and cumulative antibiotic exposure were significantly increased in patients who received prophylaxis (P < .001) (Figure 1). The pattern of antibiotic use in patients receiving levofloxacin differed from that in patients receiving no prophylaxis; levofloxacin exposure increased, but there was a concomitant reduction in exposure to cefepime/ceftazidime, vancomycin, meropenem (P < .001 for all comparisons), and aminoglycosides (P = .002) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antibiotic exposure during induction for each antibiotic prophylaxis group. Data are shown in a box plot; each box plot illustrates the upper and lower quartile (box), median (line inside box), adjacent values (whiskers), and outliers (open circles). Antibiotic exposure and cumulative antibiotic exposure were significantly greater in patients receiving levofloxacin or other prophylaxis than in those receiving no prophylaxis (P < .001 for all comparisons). However, patients receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis had less exposure to cefepime/ceftazidime, vancomycin, meropenem, or aminoglycosides (data not shown) when compared with those receiving no prophylaxis (P < .001, P < .001, P < .001, and P = .002, respectively) or other prophylaxis (P < . 001, P < .001, P < .001, and P = .04, respectively).

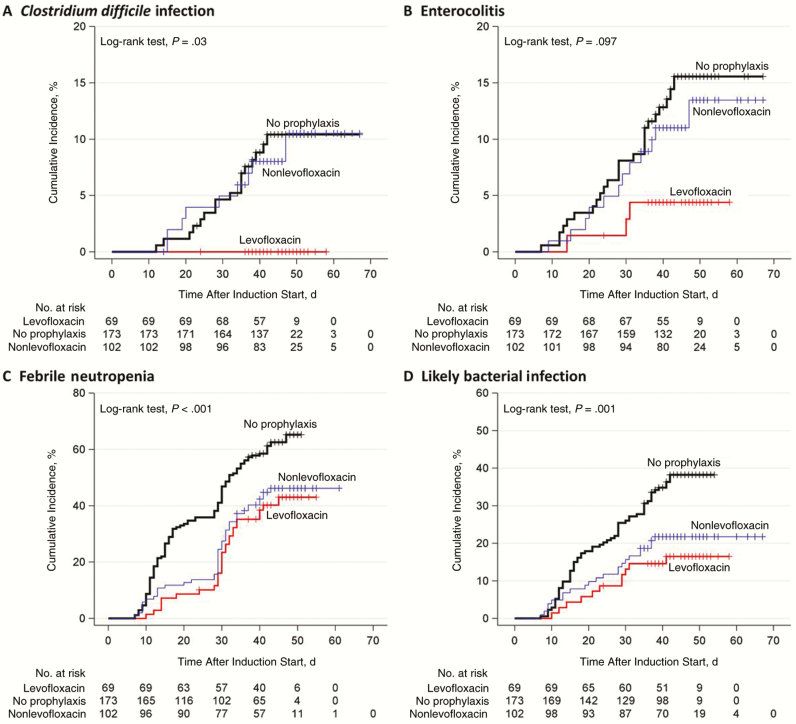

Table 3 shows the incidence of infection-related adverse events in this population. After adjustment for other covariates, patients receiving any antibacterial prophylaxis were significantly less likely than those receiving no prophylaxis to have febrile neutropenia, clinically documented infection, microbiologically documented infection, enterocolitis, C. difficile infection, likely bacterial infection, or BSI (Table 4) [12]. Reductions in C. difficile infection and enterocolitis occurred only in patients receiving fluoroquinolone prophylaxis; patients receiving cefepime-based prophylaxis had a higher risk of both (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3). Multiple logistic regression analysis (Supplementary Table S4) and Kaplan-Meier analysis showed similar results (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted Incidence of Infection-Related Adverse Events by Prophylaxis Group

| Outcome | Patients, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Prophylaxis (n = 173) | Any Prophylaxis (n = 171) | Prophylaxis Regimen | ||

| Levofloxacin (n = 69) | Other Antibiotic (n = 102) | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 106 (61.3) | 74 (43.3) | 28 (40.6) | 46 (45.1) |

| Febrile neutropenia without CDI or MDI | 60 (34.7) | 49 (28.7) | 19 (27.5) | 30 (29.4) |

| Any documented infectiona | 97 (56.1) | 71 (41.5) | 27 (39.1) | 44 (43.1) |

| CDI | 52 (30.1) | 37 (21.6) | 13 (18.8) | 24 (23.5) |

| MDI | 69 (39.9) | 43 (25.1) | 18 (26.1) | 25 (24.5) |

| BSI | 19 (11) | 9 (5.3) | 4 (5.8) | 5 (4.9) |

| Clostridium difficile infection | 17 (9.8) | 9 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 9 (8.8) |

| Any enterocolitis | 25 (14.5) | 15 (8.8) | 3 (4.3) | 12 (11.8) |

| Likely bacterial infection | 64 (37) | 33 (19.3) | 11 (15.9) | 22 (21.6) |

Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; CDI, clinically documented infection; MDI, microbiologically documented infection.

a“Any documented infection” included CDI or MDI, with or without neutropenia.

Table 4.

Propensity Score–weighted Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Effectiveness of Primary Prophylaxis

| Outcome | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted OR (95%CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Febrile neutropenia | 0.48 (.31–.74) | <.001b | 0.23 (.14–.40) | <.001b |

| Febrile neutropenia with CDI | 0.44 (.22–.89) | .02b | 0.30 (.14–.65) | .002b |

| Febrile neutropenia with MDI | 0.40 (.23–.70) | .001b | 0.25 (.14–.48) | <.001b |

| CDI | 0.64 (.39–1.05) | .08 | 0.54 (.32–.90) | .02b |

| MDI | 0.51 (.32–.80) | .004b | 0.40 (.24–.65) | <.001b |

| BSI | 0.45 (.20–1.03) | .06 | 0.30 (.13–.73) | .008b |

| Clostridium difficile infectionc | 0.51 (.22–1.18) | .11 | 0.38 (.16–.93) | .04b |

| Likely bacterial infection | 0.41 (.25–.66) | <.001b | 0.26 (.15–.45) | <.001b |

| Any enterocolitis | 0.57 (.29–1.12) | .10 | 0.44 (.21–.91) | .03b |

Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; CDI, clinically documented infection; CI, confidence interval; MDI, microbiologically documented infection; OR, odds ratio.

aThe propensity score of prophylaxis groups was estimated using a multinomial logistic regression model with age, sex, race, Down syndrome, and leukemia type as predictors; a logistic regression model was then used to model prophylaxis groups and exposure to profound neutropenia during induction as predictors of clinical outcomes, with inverse probability weighting using the propensity score.

bSignificant difference (prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis; P < .05).

cAlso adjusted for exposure to meropenem.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of time to infectious complications during induction for each antibiotic prophylaxis group. Patients receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis during induction therapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia had a lower cumulative incidence of C. difficile infection (A) than those receiving no prophylaxis (P = .008) or other prophylaxis regimens (P = .01) and a lower cumulative incidence of enterocolitis (B) than those receiving no prophylaxis (P = .03). Patients receiving any prophylaxis had a lower cumulative incidence of febrile neutropenia (C) (P < .001) and likely bacterial infection (D) (P < .001), but there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of febrile neutropenia or likely bacterial infection between patients receiving levofloxacin and those receiving other prophylaxis regimens (P = .52 and P = .36, respectively).

Levofloxacin prophylaxis alone was associated with a similar, statistically significant reduction in febrile neutropenia, microbiologically documented infection, and likely bacterial infection. (Table 5) There was also significantly less enterocolitis and C. difficile infection (Table 5). Multiple logistic regression analysis (Supplementary Table S4) and Kaplan-Meier analysis showed similar results (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S4).

Table 5.

Propensity Score–Weighted Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Effectiveness of Levofloxacin Prophylaxis

| Outcome | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted OR (95%CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levofloxacin vs no prophylaxis | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 0.43 (.24–.76) | .004a | 0.28 (.15–.52) | <.001b |

| Febrile neutropenia with CDI | 0.33 (.11–.99) | .048b | 0.25 (.09–.69) | .007b |

| Febrile neutropenia with MDI | 0.44 (.21–.93) | .03b | 0.34 (.17–.71) | .004b |

| CDI | 0.54 (.27–1.07) | .08 | 0.48 (.26–.91) | .02b |

| MDI | 0.53 (.29–.99) | .045b | 0.49 (.28–.88) | .02b |

| BSI | 0.50 (.16–1.52) | .22 | 0.42 (.15–1.16) | .09 |

| Clostridium difficile infectionc | 0.06 (<.01 to .48) | .003b | 0.03 (<.01 to .24) | <.001b |

| Likely bacterial infection | 0.32 (.16–.66) | .002b | 0.24 (.12–.48) | <.001b |

| Any enterocolitis | 0.27 (.08–.92) | .04b | 0.23 (.08–.67) | .008b |

| Levofloxacin vs other prophylaxis | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 0.83 (.45–1.54) | .56 | 1.17 (.64–2.14) | .60 |

| Febrile neutropenia with CDI | 0.64 (.19–2.15) | .47 | 0.74 (.25–2.19) | .59 |

| Febrile neutropenia with MDI | 1.16 (.48–2.82) | .74 | 1.68 (.74–3.84) | .21 |

| CDI | 0.75 (.35–1.61) | .47 | 0.85 (.44–1.65) | .63 |

| MDI | 1.09 (.54–2.19) | .82 | 1.41 (.76–2.63) | .27 |

| BSI | 1.19 (.31–4.61) | .80 | 1.85 (.54–6.35) | .33 |

| C. difficile infectionc | 0.07 (<.01 to .57) | .008b | 0.04 (<.01 to .36) | <.001b |

| Likely bacterial infection | 0.69 (.31–1.53) | .36 | 0.85 (.41–1.74) | .65 |

| Any enterocolitis | 0.34 (.09–1.26) | .11 | 0.38 (.12–1.14) | .08 |

Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; CDI, clinically documented infection; CI, confidence interval; MDI, microbiologically documented infection; OR, odds ratio.

aThe propensity score of prophylaxis groups was estimated using a multinomial logistic regression model with age, sex, race, Down syndrome, and leukemia type as predictors; then a logistic regression model was used to model prophylaxis groups and exposure to profound neutropenia during induction as predictors of clinical outcomes, with inverse probability weighting using the propensity score.

bSignificant difference (P < .05).

cAlso adjusted for exposure to meropenem.

Compared with patients receiving other prophylaxis regimens, patients receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis had a similar risk of febrile neutropenia, clinically documented infection, microbiologically documented infection, likely bacterial infection, and BSI (Table 5). However, levofloxacin prophylaxis was associated with a significantly lower rate of C. difficile infection (adjusted odds ratio, 0.04; 95%confidence interval, <.01 to .36; P < .001) (Table 5). There was some heterogeneity among alternative regimens: Pooled ciprofloxacin-based regimens, predominantly ciprofloxacin plus vancomycin, seemed to be superior for some outcomes, but no individual regimen was significantly superior to levofloxacin (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3). Multiple logistic regression analysis (Supplementary Table S4) and Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S4) again showed similar results.

There were 28 episodes of bacterial BSI in 28 patients during the study period (Supplementary Table S5). Although BSI was less common in patients receiving prophylaxis, the causative organisms were similar (Supplementary Table S5), and the proportions of BSI episodes complicated by severe sepsis or requirement for urgent intervention did not differ between patients receiving prophylaxis and those receiving none (2 of 9 [22.2%] vs 4 of 19 [21.1%], respectively; P > .99). One patient receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis developed bacteremia caused by an extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli strain that was resistant to levofloxacin and cefepime.

DISCUSSION

In this largest study to date, primary antibacterial prophylaxis during induction therapy for ALL was associated with markedly reduced rates of febrile neutropenia, clinical or microbiologically documented infection, likely bacterial infection, and BSI. Although prophylaxis increased overall antibiotic exposure, patients receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis had less exposure to cefepime/ceftazidime, vancomycin, and aminoglycosides. Unexpectedly, prophylaxis with levofloxacin drastically reduced the risk of C. difficile infection and all-cause enterocolitis.

The observed reduction in infection and febrile neutropenia extends data obtained from adult populations. A meta-analysis of antibacterial prophylaxis in predominantly adult patients showed that prophylaxis reduced febrile episodes, documented infection, infection-related mortality, and all-cause mortality [6]. Few studies of fluoroquinolone prophylaxis in children with leukemia have been published; most showed a reduction in infection-related adverse events [9, 21–24], but some showed a paradoxical increase in these complications [10, 25]. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis can also reduce bacterial infection [26] but was routine in all groups in this study.

The current study provides new information by comparing prophylaxis with levofloxacin, a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone, to alternative prophylaxis regimens and by excluding patients who had no opportunity to receive prophylaxis, carefully controlling for potential confounders and examining C. difficile infection. Our study has several strengths related to the institutional setting and study design. All patients were treated according to a single protocol at a single institution and were provided with high-quality supportive care [2, 27, 28]. We used prespecified standard definitions of febrile neutropenia, clinically or microbiologically documented infection (which includes nonbacterial infections), and BSI [15]. We added the category of likely bacterial infection, comprising infections typically attributed to bacteria.

Patients with early infection or febrile neutropenia were excluded from analysis because they might falsely raise the apparent rate of infection in the no-prophylaxis group. Similarly, excluding patients who had an infection before receiving chemotherapy or who received prolonged treatment for fever at presentation ensured that only potentially preventable outcomes were analyzed. Not all patients with fever at presentation were excluded, because fever occurs in about 59% of patients and is rarely related to infection [29]. Detailed chart review ensured appropriate classification of prophylaxis regimens. Although observational studies of this type can be subject to selection bias, we aimed to ameliorate such bias by applying a propensity score–weighted logistic regression model to account for differences between groups.

The observed reduction in enterocolitis and C. difficile infection associated with levofloxacin prophylaxis is important because these conditions can cause serious illness, malnutrition, chemotherapy delay, or poor absorption of medications for cancer treatment, all of which can reduce the chance of cure [8, 30–33]. Furthermore, 2 studies found that C. difficile infection in hospitalized children markedly increased the risk of all-cause mortality [8, 34]. Patients receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis were protected from this infection, despite an incongruous increase in their total antibiotic exposure [30, 32]. A recent study in children with ALL found that exposure to antipseudomonal cephalosporin and β-lactam antibiotics, especially cefepime, was the most important contributor to the risk of C. difficile infection, but this study did not assess the effects of quinolone exposure [30].

In an animal model, fluoroquinolone antibiotics did not impair resistance to colonization with C. difficile, whereas β-lactam antibiotics did [7]. Therefore, using fluoroquinolone prophylaxis to reduce exposure to other antibiotics might prevent C. difficile infection, but this is the first study to show such a benefit. Previous studies of quinolone prophylaxis in adults showed no such effect on C. difficile infection [6], and some studies have even identified fluoroquinolone exposure as a risk factor for C. difficile infection [35]. The difference in the current study may be related to the marked reduction in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy or to predominance of quinolone-susceptible C. difficile [2, 35].

Other potentially confounding variables that affect the risk of C. difficile infection in children with leukemia include shorter hospital stay and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration [36], but there was no change in discharge guidelines during the study period, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was not used in this protocol. Importantly, the institutional rate of C. difficile infection did not change during the study period (Supplementary Figure S5). The effect of prophylaxis during induction on C. difficile infection in postinduction chemotherapy cannot be determined from this study.

The study has some limitations. Grouping alternative prophylaxis regimens provides a robust comparison group but can mask differences between heterogeneous regimens (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3). The study was not powered to detect a difference in outcomes between different fluoroquinolones, and the reduction in C. difficile infection was seen in both levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin-based prophylaxis regimens (Supplementary Table S3). Until 2014, antimicrobial prophylaxis was provided at the discretion of the treating physician, so the potential for confounding is an important issue, especially in the context of a single-center study, which can amplify the effects of confounders. Clinicians may have preferentially prescribed prophylaxis to patients at higher risk of infection, but this confounding by indication would be expected to mask, rather than inflate, the benefits of prophylaxis.

Other than neutropenia duration, risk factors for infection did not differ significantly between groups (Table 2); known variables were addressed by a propensity score–weighted multivariate logistic regression analysis (Tables 4 and 5). Another potential confounder is the time period, because routine levofloxacin was introduced in 2014 and the other groups were treated in 2008–2014. There is no evidence that this explains the differences between groups, because there were no trends in infection rates in study patients who received no prophylaxis before 2014 (Supplementary Figure S6) and no significant decrease in institutional rates of hospital-acquired infection or C. difficile infection during the entire study period (Supplementary Figure S5).

Antimicrobial stewardship interventions introduced during the study period included prospective audit with feedback for meropenem and linezolid use; however, no intervention aimed at reducing the use of vancomycin, cefepime/ceftazidime, or aminoglycosides. Meropenem exposure was included as a covariate in the analysis of C. difficile infections to reduce the risk of confounding by these stewardship interventions. In 2015, a 2-month nationwide shortage of cefepime necessitated a temporary modification of institutional guidelines to include ceftazidime plus vancomycin as first-line therapy for febrile neutropenia. Accordingly, ceftazidime and cefepime exposure were merged in the final analysis to avoid a spurious reduction in cefepime exposure during the shortage. Despite these efforts to address and ameliorate the effects of identified variables, confounding of the study by unidentified variables remains possible.

The prolonged neutropenia in patients receiving prophylaxis might be related to the indication for prophylaxis and was, therefore, included in the multivariate analysis. However, a lower neutrophil nadir was seen in an Indonesian study of children receiving ciprofloxacin prophylaxis, raising the possibility of neutropenia as an adverse effect of fluoroquinolones [10]. A related consideration is that infection-related mortality during leukemia therapy is more common in low-income countries and malnourished patients, so our findings may not be generalizable to those settings [10].

The implementation of antibacterial prophylaxis has been limited by concerns regarding possible adverse consequences, especially the development of antibiotic resistance [37]. Although antibiotic-resistant infections did not significantly increase in this study, the sample size and time period were inadequate to measure the medium- or long-term risk. Studies of antibacterial resistance after levofloxacin prophylaxis have yielded mixed results. A meta-analysis found no significant increase in quinolone-resistant infection (relative risk, 1.2; 95%confidence interval, .8–1.7), but the follow-up period in these studies was insufficient to address the question of long-term resistance [6]. Other groups have reported increased resistance, including cross-resistance, after extended use of quinolones [38, 39], although this did not necessarily negate the benefit of prophylaxis [38]. In the current study, exposure to antipseudomonal β-lactam antibiotics, aminoglycosides, and vancomycin was reduced. This suggests that fluoroquinolone prophylaxis might shift antibiotic use away from agents less crucial for treating infection, thereby balancing the overall increase in exposure. Large-scale long-term investigations are needed to assess this prospect [39].

Ours is the first study to examine the effects of primary antibacterial prophylaxis with levofloxacin on serious infections and antibiotic exposure in children undergoing induction therapy for ALL. Although all prophylaxis regimens, including levofloxacin, reduced the risk of febrile neutropenia and systemic infection, levofloxacin prophylaxis also shifted antibiotic use away from agents typically used to treat infection and dramatically reduced the risk of enterocolitis and C. difficile infection. There was no documented increase in breakthrough infections with resistant organisms, but this remains possible. These findings support the targeted use of levofloxacin prophylaxis in children and adolescents with ALL who are undergoing induction therapy, with close long-term monitoring of antibiotic resistance patterns.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Keith A. Laycock, PhD, ELS, Elaine Tuomanen, MD, Jose Ferrolino MD, and Marnie Dorsey for support in the preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA21765, CA36401-26S1, and GM92666) and by ALSAC.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Christensen MS, Heyman M, Mottonen M et al. Treatment-related death in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in the Nordic countries: 1992–2001. Br J Haematol 2005; 131:50–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inaba H, Pei D, Wolf J et al. Infection-related complications during treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Oncol 2017; 28:386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Connor D, Bate J, Wade R et al. Infection-related mortality in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an analysis of infectious deaths on UKALL2003. Blood 2014; 124:1056–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slats AM, Egeler RM, van der Does-van den Berg A et al. Causes of death–other than progressive leukemia–in childhood acute lymphoblastic (ALL) and myeloid leukemia (AML): the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group experience. Leukemia 2005; 19:537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fiser RT, West NK, Bush AJ, Sillos EM, Schmidt JE, Tamburro RF. Outcome of severe sepsis in pediatric oncology patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005; 6:531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gafter-Gvili A, Fraser A, Paul M et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial infections in afebrile neutropenic patients following chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 1:CD004386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR et al. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature 2015; 517:205–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sammons JS, Localio R, Xiao R, Coffin SE, Zaoutis T. Clostridium difficile infection is associated with increased risk of death and prolonged hospitalization in children. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yousef AA, Fryer CJ, Chedid FD, Abbas AA, Felimban SK, Khattab TM. A pilot study of prophylactic ciprofloxacin during delayed intensification in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004; 43:637–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Widjajanto PH, Sumadiono S, Cloos J, Purwanto I, Sutaryo S, Veerman AJ. Randomized double blind trial of ciprofloxacin prophylaxis during induction treatment in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the WK-ALL protocol in Indonesia. J Blood Med 2013; 4:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2730–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e56-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lehrnbecher T, Phillips R, Alexander S et al. ; International Pediatric Fever and Neutropenia Guideline Panel Guideline for the management of fever and neutropenia in children with cancer and/or undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:4427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events v3.0 (CTCAE) NCI, NIH, DHHS. August 9, 2006.

- 15. Haeusler GM, Phillips RS, Lehrnbecher T, Thursky KA, Sung L, Ammann RA. Core outcomes and definitions for pediatric fever and neutropenia research: a consensus statement from an international panel. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62:483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santolaya ME, Alvarez AM, Becker A et al. Prospective, multicenter evaluation of risk factors associated with invasive bacterial infection in children with cancer, neutropenia, and fever. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:3415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line-associated bloodstream infection) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/4PSC_CLABScurrent.pdf. Accessed 26 April 2017.

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHSN organism list (all organisms, top organisms, common commensals, MBI organisms, and UTI bacteria) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/XLS/master-organism-Com-Commensals-Lists.xlsx. Accessed 26 April 2017.

- 19. Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A; International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005; 6:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2002; 21:2409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cruciani M, Concia E, Navarra A et al. Prophylactic co-trimoxazole versus norfloxacin in neutropenic children–perspective randomized study. Infection 1989; 17:65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laoprasopwattana K, Khwanna T, Suwankeeree P, Sujjanunt T, Tunyapanit W, Chelae S. Ciprofloxacin reduces occurrence of fever in children with acute leukemia who develop neutropenia during chemotherapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:e94–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sulis ML, Blonquist TM, Athale UH et al. Effectiveness of antibacterial prophylaxis during induction chemotherapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015; 126: 249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yeh TC, Liu HC, Hou JY et al. Severe infections in children with acute leukemia undergoing intensive chemotherapy can successfully be prevented by ciprofloxacin, voriconazole, or micafungin prophylaxis. Cancer 2014; 120:1255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Felsenstein S, Orgel E, Rushing T, Fu C, Hoffman JA. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes of quinolone prophylaxis in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34:e78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rungoe C, Malchau EL, Larsen LN, Schroeder H. Infections during induction therapy for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. the role of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX-TMP) prophylaxis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010; 55:304–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCullers JA, Williams BF, Wu S et al. Healthcare-associated infections at a children’s cancer hospital, 1983–2008. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pui CH, Evans WE. A 50-year journey to cure childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol 2013; 50:185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khurana M, Lee B, Feusner JH. Fever at diagnosis of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: are antibiotics really necessary? J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2015; 37:498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fisher BT, Sammons JS, Li Y et al. Variation in risk of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection across β-lactam antibiotics in children with new-onset acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014; 3:329–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sandora TJ, Fung M, Flaherty K et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:580–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tai E, Richardson LC, Townsend J, Howard E, Mcdonald LC. Clostridium difficile infection among children with cancer. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:610–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Blank P, Zaoutis T, Fisher B, Troxel A, Kim J, Aplenc R. Trends in Clostridium difficile infection and risk factors for hospital acquisition of Clostridium difficile among children with cancer. J Pediatr 2013; 163:699–705 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dingle KE, Didelot X, Quan TP et al. ; Modernising Medical Microbiology Informatics Group Effects of control interventions on Clostridium difficile infection in England: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:411–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sung L, Aplenc R, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, Lehrnbecher T, Gamis AS. Effectiveness of supportive care measures to reduce infections in pediatric AML: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood 2013; 121:3573–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haeusler GM, Slavin MA. Fluoroquinolone prophylaxis: worth the cost? Leuk Lymphoma 2013; 54:677–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kern WV, Klose K, Jellen-Ritter AS et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance of Escherichia coli at a cancer center: epidemiologic evolution and effects of discontinuing prophylactic fluoroquinolone use in neutropenic patients with leukemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005; 24:111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Macesic N, Morrissey CO, Cheng AC, Spencer A, Peleg AY. Changing microbial epidemiology in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: increasing resistance over a 9-year period. Transpl Infect Dis 2014; 16:887–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.