Abstract

The hen is an attractive animal model for in vivo testing of agents that thwart ovarian carcinogenesis because ovarian cancer in the domestic hen features clinical and molecular alterations that are similar to ovarian cancer in humans, including a high incidence of p53 mutations. The objective of the study was to test the potential ovarian cancer chemopreventive effect of the p53 stabilizing compound CP-31398 on hens that spontaneously present the ovarian cancer phenotype. Beginning at 79 wk of age, 576 egg-laying hens (Gallus domesticus) were randomized to diets containing different amounts of CP-31398 for 94 wk, 5 d, comprising a control group (C) (n = 144), which was fed a diet containing 0 ppm (mg/kg) of CP-31398; a low-dose treatment (LDT) group (n = 144), which was fed a diet containing 100 ppm of CP-31398; a moderate-dose treatment (MDT) group (n = 144) which was fed a diet containing 200 ppm of CP-31398; and a high-dose treatment (HDT) group (n = 144), which was fed a diet containing 300 ppm of CP-31398. Hens were killed at 174 wk of age to determine the incidence of ovarian and oviductal adenocarcinomas. Whereas the incidence of localized and metastatic ovarian cancers in the MDT and HDT groups was significantly lower (up to 77%) compared to levels in the C and LDT groups (P < 0.05), the incidence of oviductal cancer was unaffected by CP-31398. CP-31398 appears to be an effective tool for chemoprevention against ovarian malignancies, but does not appear to affect oviductal malignancies.

Keywords: avian, CP-31398, oviduct, ovarian, cancer

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of female cancer mortality and the most lethal of all gynecological cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 44% (Jemal et al., 2007; American Cancer Society, 2013). Epidemiologic evidence has linked the number of lifetime ovulatory cycles to ovarian cancer risk (Jemal et al., 2007; American Cancer Society, 2013). The pathogenesis of ovarian cancer has been attributed to ovulation-induced damage of the ovarian epithelium, leading to the incessant ovulation hypothesis (Fathalla, 1971), which suggests that exposure to estradiol and gonadotropins, combined with repeated insult to the ovarian surface epithelium at each ovulation may cause DNA damage, dysplasia, and the development of ovarian cancer. Factors associated with decreased ovulation such as oral contraceptives, increased parity, and lactation have been linked to decreased ovarian cancer risk (Hunn and Rodriguez, 2012). Although human ovarian cancer is presumed to arise from the ovarian surface epithelium (Auersperg et al., 2001), recent studies suggest that the fallopian tubes may represent the site of origin of cancer cells that ultimately implant in the surface epithelium of the ovary (Kurman and Shih, 2010).

The domestic hen (Gallus domesticus) has been described as a preclinical model suitable to study epithelial ovarian carcinoma development, including potential prevention modalities in humans (Lu et al., 2009). The prevalence of spontaneous ovarian adenocarcinoma in the aged hen exceeds that in all other species, presumably due to its high lifetime number of ovulations (Fredrickson, 1987). Similar to humans, decreased egg production (ovulation), due to either caloric restriction or oral contraceptives has been associated with decreased ovarian cancer in the hen, supporting the incessant ovulation hypothesis (Carver et al., 2011; Treviño et al., 2012). Additionally, progestins confer a cancer preventive effect unrelated to ovulation (Rodriguez et al., 2013). Significantly, p53 mutations in ovarian cancer of hens are quite common and appear to be associated with the number of lifetime ovulations, similar to human ovarian cancers (Hakim et al., 2009).

The synthetic styrylquinazoline CP-31398 may aid in the restoration of the DNA-binding activity of p53 in mutant cells (Demma et al., 2004). CP-31398 is an ideal candidate for an avian chemopreventive study because of its ability to restore the wild-type phenotype of cells where p53 has been damaged and mutated over time. In a rodent study, CP-31398 was found to reduce the incidence of intestinal tumor development through a proposed stabilization of p53 function (Rao et al., 2008). The objective of the chemopreventive trial was to evaluate the effect of CP-31398 on the incidence of spontaneously occurring epithelial ovarian and oviductal carcinomas of the hen employing egg production, feed consumption, and body weight as surrogate biomarkers of ovarian epithelium damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Husbandry

Eight-hundred-seventy-six sexually mature single comb white leghorn Hy-Line W-36 strain commercial layer hens were chosen for the chemopreventive trial. The birds were initially in commercial production, then at approximately 68 wk of age they were transferred to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture Piedmont Research Station in Salisbury, NC, for the duration of the study. To acclimate the flock to new housing conditions, the hens were maintained for approximately 11 wk before the initiation of the chemopreventive treatment. The birds were fed a corn-soy based maintenance diet prepared at the North Carolina State University Feed Mill (Supplementary Table S1). Water and feed were supplied ad libitum throughout the life of the flock.

The temperature of the house was maintained at 23°C ± 6°C, with the relative humidity controlled at 70% ± 5%. The ventilation rate varied between 0.35 ft3 per min per bird and 6.25 ft3 per min per bird, increasing along with increased house temperatures. The light:dark cycle was 14 h light:10 h dark, using 20 lux lighting for the light cycle. The birds were housed with one hen per single wire cage, measuring 24″ x 20″ x 23.5″, at 480 in2. For identification purposes, the wings of every hen were banded with tags specifying the replicate number, cage number, and bird number for that particular hen. Each replicate consists of 4 birds within the same treatment group that are housed in succession and share feed. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of North Carolina State University approved all animal procedures.

Chemoprevention Study

The 876 hens participating in the study were approximately 79 wk at the start of the chemopreventive trial. To determine a baseline incidence of ovarian and oviductal cancers, 300 birds from the flock were killed by cervical dislocation, and examined for the presence of tumors. The remaining 576 hens were randomized into a control and 3 treatment groups of 144 birds each. Treatment groups were administered the layer hen maintenance diet containing CP-31398 (>99% purity; Indofine Chemical Company, Inc. Hillsborough, NJ), protected from light and stored desiccated at 2 to 6°C. The control group (C) received feed containing zero ppm (mg/kg) CP-31398, the low- dose treatment group (LDT) received feed containing 100 ppm CP-31398, the medium-dose treatment group (MDT) received feed containing 200 ppm CP-31398, and the high-dose treatment group (HDT) received feed containing 400 ppm CP-31398. Experimental diets were prepared by mixing concentrated CP-31398 premixes with the standard soy-corn maintenance diet using an industrial ribbon mixer to ensure uniform dispersion of the drug. CP-31398 intake per hen was determined based on the daily feed consumption of the hens prior to the initiation of the chemopreventive trial, which was approximately 100 g feed/hen/day. The daily intake of CP-31398 was targeted at zero mg/d for the C group, 10 mg/d for the LDT treatment group (100 mg/kg*0.10 kg), 20 mg/d for the MDT group (200 mg/kg*0.10), and 40 mg/d for the HDT group (400 mg/kg*0.10 kg). The hens were fed these treatment diets for 94 wk, 4 d until the termination of the study. By study wk 12, hens in the HDT group (400 ppm CP-31398) experienced liver toxicity based on hepatic necrosis found at necropsy. Subsequently, hens receiving 400 ppm of CP-313198 were removed from treatment for 30 d, and were then reintroduced at 300 ppm CP-31398 in the 16th wk of the trial. The estimated daily intake of CP-31398 was recalculated at 30 mg/d (300 mg/kg*0.10 kg). The change in dosage protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of North Carolina State University. During the remaining 80 wk of the chemopreventive study, no CP-31398-induced liver toxicity was evident.

The egg production, feed consumption, and body weight of all birds in the flock were closely monitored. Technicians observed the flock at least twice daily, surveilling bird health status and recording the number of eggs produced within each replicate per diem. The average egg production per bird for each 4-week period by treatment group was calculated using the following formula:

|

Individual body weights of all hens were documented at the initiation and termination of the study, but for the duration of the trial, one of the 4 birds from each replicate was randomly chosen and weighed once every 8 weeks. The weight of feed provided to the replicates was recorded to calculate the feed intake of the hens. The total average feed consumption per bird was calculated once every 4 wk using the following formula:

|

Sample Collection

Mortalities in the flock found during routine observation were immediately removed from the cage and stored in a refrigerator maintained between 4 and 6°C until an exploratory necropsy could be performed to determine the cause of death. Moribund and non-ambulatory hens showing signs of clinical symptoms or injury were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and also were stored for necropsy. Mortalities and euthanized hens were necropsied weekly to determine the cause of death, all tumors and perceived adenocarcinomas were removed, and excised tissue was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours. The samples were then moved to 70% ethanol and stored at approximately 4°C until a histological analysis could be completed.

At the end of the 95-week chemoprevention trial, the remaining 401 birds of approximately 174 wk of age were euthanized by cervical dislocation and tumor incidence was recorded to determine the flock's final health status. The representative tissue samples collected during the necropsy were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, transferred to 70% ethanol, and stored at approximately 4°C for histological analysis. In addition to adenocarcinoma collection at the final necropsy, the liver and heart were excised from 20 cancer-free birds out of each treatment group, and 18 cancer-free birds from the control group. The 78 liver and heart samples collected were weighed to assess any possible toxic effects of CP-31398.

Tumor Classification

The gross classification system used to assess tumors was based on a previous study on the staging of primary malignant ovarian tumors in hens (Barua et al., 2009). Classes 5 to 7 were added to the original classification system of classes 1 to 4 to more precisely determine the full range of gynecological cancers (Harris et al., 2014) (Table 1). Gastrointestinal cancer mortalities and all other fatalities are considered separately from those with reproductive involvement.

Table 1.

Gross pathology classifications of avian tumors.

| Cancer status | Classification |

|---|---|

| Ovarian cancer only | Class 1 |

| Ovarian and oviductal cancer | Class 2 |

| Ovarian and oviductal metastasized to GI tract | Class 3 |

| Ovarian and oviductal metastasized to distant organs | Class 4 |

| Oviductal cancer only | Class 5 |

| Oviductal cancer metastasized, no ovarian involvement | Class 6 |

| Ovarian cancer metastasized, no oviductal involvement | Class 7 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer only, no reproductive involvement | GI only |

| No reproductive or GI cancer (includes liver toxicity) | Normal/other |

Histological Analysis

Tissues that had been fixed in 10% neutral formalin buffer for 24 h were moved to 70% ethanol and stored in cassettes at 4°C. The samples were dehydrated in ethanol, cleared with xylene, embedded in paraffin wax, and were submitted for histopathological analysis by a board certified veterinary pathologist. Embedded tissues were sectioned and mounted on glass microscope slides for observation. The slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and were assessed based on the classification system listed in Table 2 (Harris et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Histopathology classifications of avian epithelial tumors.

| Albuminous adenocarcinoma classification | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Characteristics |

| Grade 1 | Well-differentiated–mitosis rare to absent, defined pattern, most common classification |

| Grade 2 | Intermediate differentiation–mitosis rare to occasional, tubular pattern present but not distinct |

| Grade 3 | Poorly differentiated–mitosis common, cells highly anaplastic, least common classification |

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical program JMP9 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Data pertaining to egg production, feed consumption, and body weights of the hens were all evaluated using the one-way analysis of variance statistical model, and means were compared using the Tukey-Kramer Honestly Significant Difference test. Analyses of mortality and cancer incidence with respect to treatment group and tumor classification data were performed using a chi-squared test, followed by a 2-proportion z-test for all sample comparisons. Differences were considered significant at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Egg Production

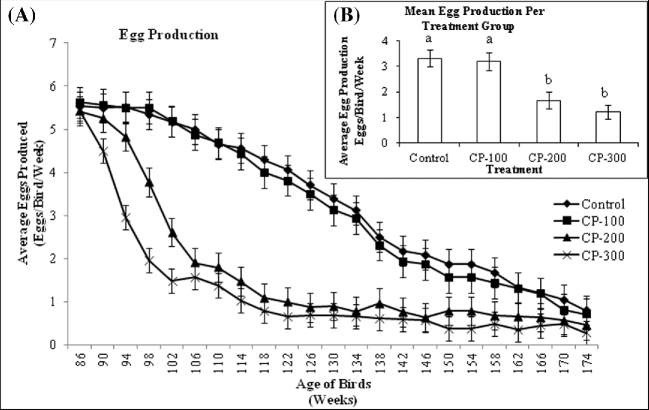

Egg production in the hen is a measure of the number of ovulations and thus may provide an estimate of the damage sustained by the ovarian surface epithelium over time. Weekly egg production was the same across all treatment groups before the start of the study, and steadily declined over the course of the trial (Figure 1). By 94 wk of age, the HDT group had significantly lower egg production than controls (P < 0.05). Hens ingesting 200 ppm CP-31398 (MDT group) also experienced an observable decrease in egg production by 94 wk of age (P < 0.05). Egg production in the HDT and MDT groups became similar by 106 weeks. During the following 56 wk, egg production in the C and LDT groups was higher than the MDT and HDT groups (P < 0.05). At 162 wk, the weekly egg production of all treatment groups became the same for the remaining 12 wk of the trial.

Figure 1.

A: Mean weekly egg production per bird for all treatment groups from 86 to 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 144; CP-100, n = 144; CP-200, n = 144; CP-300, n = 144. B: Mean weekly egg production per bird for each treatment group from 86 to 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 144; CP-100, n = 144; CP-200, n = 144; CP-300, n = 144. Means with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

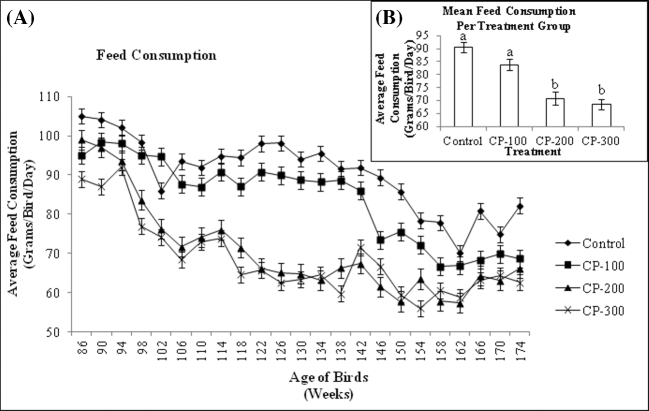

Feed Consumption and Body Weight

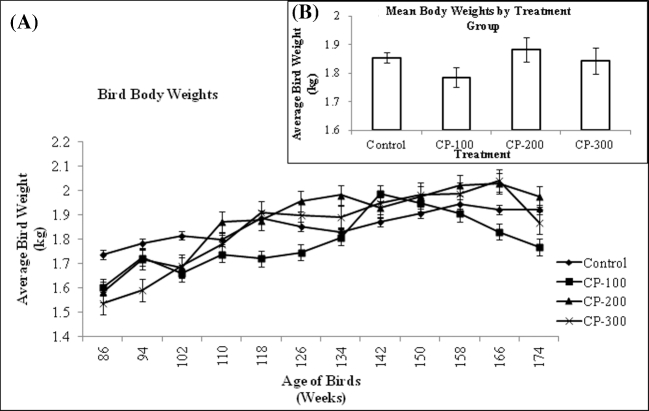

As egg production declined, there was also an expected decline in feed intake (Figure 2). The feed intake of hens fed 200 to 300 ppm CP-31398 (MDT and HDT groups) was similar (P > 0.05) throughout the trial. Birds fed zero or 100 ppm CP-31398 (C and LDT groups) also showed a similar feed intake (P > 0.05), and maintained an overall higher feed intake than the higher dosage groups until wk 166 when only birds in the C group had a significantly higher feed intake than the other groups until the termination of the study. The composite feed consumption data in Figure 2B shows that birds in the C and LDT treatment groups had significantly higher feed intake than those in the MDT and HDT groups. The expected daily feed intake was 100 g/bird/d, but the actual average daily feed consumption was approximately 90 g/bird/d for C birds, 84 g/bird/d for LDT birds, 71 g/bird/d for MDT birds, and 69 g/bird/d for HDT birds. Using the observed daily feed intake and average body weight for each treatment group, the calculated average daily CP-31398 intake per bird was zero mg/kg/d for C birds ([zero mg/kg CP * 0.090 kg feed/d]/1.85 kg body weight), 4.70 mg/kg/d for LDT birds ([100 mg/kg CP * 0.084 kg feed/d]/1.79 kg body weight), 7.54 mg/kg/d for MDT birds ([200 mg/kg CP * 0.071 kg feed/d]/1.88 kg body weight), and 11.23 mg/kg/d for HDT birds ([300 mg/kg CP * 0.069 kg feed/d]/1.84 kg body weight). Body weight of hens increased in each treatment group over the course of the trial, despite decreased feed intake, including hens fed 300 ppm CP-31398. In addition, there was no relationship between treatment and body weight, nor was there any significant difference between treatment groups in body weight over the course of the study, indicating no adverse effects by CP-31398 (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 2.

A: Mean daily feed consumption (g) per bird for each treatment group from 86 to 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 144; CP-100, n = 144; CP-200, n = 144; CP-300, n = 144. B: Mean daily feed consumption (g) per bird for each treatment group from 86 to 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 144; CP-100, n = 144; CP-200, n = 144; CP-300, n = 144. Means with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

A: Mean body weights (kg) per bird for each treatment group from 86 to 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 144; CP-100, n = 144; CP-200, n = 144; CP-300, n = 144. B: Mean body weights (kg) per bird from 86 to 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 144; CP-100, n = 144; CP-200, n = 144; CP-300, n = 144. Values are not statistically different (P > 0.10).

Tumor Incidence

The 300 birds examined during the baseline necropsy preceding the initiation of the chemopreventive trial were classified by the system listed in Table 1 (Barua et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2014). One hen was found with oviductal cancer only (class 5), and 2 were classified as having metastasized reproductive and gastrointestinal cancers (class 4). The gross pathology of all 175 birds necropsied before 174 wk of age is shown in Table 3. Fifty-five birds were necropsied in the control group, 42 in the LDT group, 37 in the MDT group, and 41 in the HDT group. There is a significantly lower incidence of oviductal (class 5) and oviductal metastasized cancer (class 6) in birds receiving 300 ppm CP-31398, compared to the control birds receiving zero ppm. The number of birds in the normal/other category for the HDT group is elevated, in part, because of the initial liver toxicity and hemorrhage in those birds. Table 4 contains the results based on gross pathology at the mass necropsy of the remaining 401 birds at 174 wk of age. Eighty-nine birds were necropsied in the control group, 102 in the LDT group, 107 in the MDT group, and 103 in the HDT group. Birds treated with 200 ppm and 300 ppm CP-31398 showed a significantly lower level of ovarian cancer (class 1), ovarian and oviductal cancers metastasized (classes 3 and 4), ovarian cancer metastasized without oviductal involvement (class 7), and gastrointestinal cancers.

Table 3.

Cumulative mortality by classification prior to final necropsy (at 174 wk old).

| Pre-necropsy sample data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Low dose | Moderate dose | High dose | |

| Cancer | (0 ppm CP-31398) | (100 ppm CP-31398) | (200 ppm CP-31398) | (300 ppm CP-31398) |

| Ovarian only (class 1) | 4% | 7% | 3% | 0% |

| Ovarian and oviductal (class 2) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Ovarian and oviductal metastasized (class 3 and 4) | 16% | 17% | 11% | 5% |

| Oviductal only (class 5) | 9%a | 5%a,b | 5%a,b | 0%b |

| Oviductal metastasized, no ovarian (class 6) | 15%a | 7%a,b | 3%b | 2%b |

| Ovarian metastasized, no oviductal (class 7) | 2% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| GI only, no reproductive involvement | 9% | 5% | 8% | 2% |

| Normal/other | 45%a | 55%a,b | 70%b | 90%c |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

a–cConfirmed by a board certified veterinary histopathologist. Values in a row with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Tumor incidence of flock by treatment group at final necropsy (174 wk old).

| Necropsy sample data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Low dose | Moderate dose | High dose | |

| Cancer | (0 ppm CP-31398) | (100 ppm CP-31398) | (200 ppm CP-31398) | (300 ppm CP-31398) |

| Ovarian only (class 1) | 1%a,c | 5%a | 0%b,c | 1%a,c |

| Ovarian and oviductal (class 2) | 3% | 2% | 2% | 0% |

| Ovarian and oviductal metastasized (class 3 & 4) | 20%a | 19%a | 3%b | 3%b |

| Oviductal only (class 5) | 7% | 7% | 5% | 8% |

| Oviductal metastasized, no Ovarian (class 6) | 7% | 4% | 3% | 3% |

| Ovarian metastasized, no oviductal (class 7) | 6%a,b | 11%a | 1%b | 1%b |

| GI only, no reproductive involvement | 8%a,b | 9%b,c | 1%d | 2%a,d |

| Normal/other | 48%a | 44%a | 86%b | 83%b |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

a–dConfirmed by a board certified veterinary histopathologist. Values in a row with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

A composite of the overall gross pathology of all 576 birds in the trial is shown in Table 5. 44.4% of control group birds had ovarian or oviductal cancers, versus 13.19% of those in the high dose group with reproductive cancer. 2% of birds fed zero ppm CP, 6% of the 100 ppm hens, 1% of the 200 ppm hens, and 1% of the 300 ppm hens were classified as having ovarian cancers, indicating a significantly lower incidence of ovarian malignancies in birds receiving higher levels of the chemopreventive compound. There were also significantly fewer gastrointestinal cancers in birds receiving high doses of CP-31398 compared with the control and low dose groups. All tumor classifications were confirmed by the histopathological analysis, as shown in Supplemental Table S2.

Table 5.

Cumulative tumor incidence for flock by treatment group. Values represent the percentage of birds in each category.

| Total study sample data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Low dose | Moderate dose | High dose | |

| Cancer | (0 ppm CP-31398) | (100 ppm CP-31398) | (200 ppm CP-31398) | (300 ppm CP-31398) |

| Ovarian only (class 1) | 2%a,b | 6%a | 1%c | 1%b,c |

| Ovarian and oviductal (class 2) | 2% | 1% | 1% | 0% |

| Ovarian and oviductal metastasized (class 3 & 4) | 19%a | 18%a | 5%b | 3%b |

| Oviductal only (class 5) | 8% | 6% | 5% | 6% |

| Oviductal metastasized, no ovarian (class 6) | 10%a | 5%a,b | 3%a,b | 3%b |

| Ovarian metastasized, no oviductal (class 7) | 4%a,b | 9%a | 1%b | 1%b |

| GI only, no reproductive involvement | 8%a | 8%a | 3%a,b | 2%b |

| Normal/other | 47%a | 47%a | 82%b | 85%b |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

a–cConfirmed by a board certified veterinary histopathologist Values in a row with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

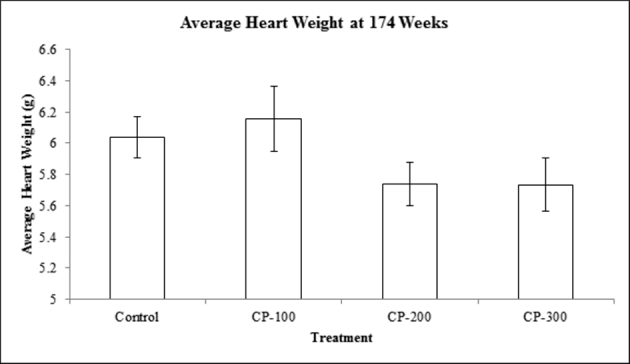

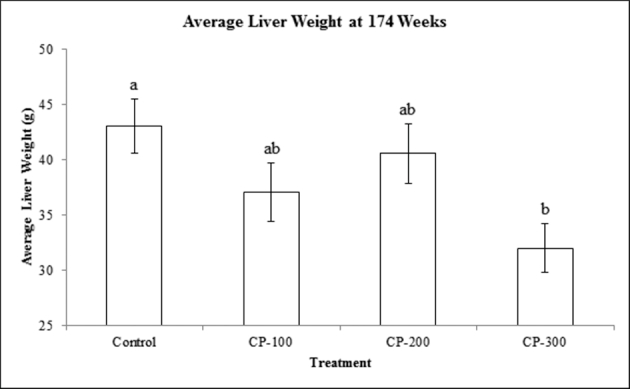

Heart and Liver Weights

The bird heart weights were the same, revealing that there is no significant effect of CP-31398 treatment on heart weight (P > 0.1) (Figure 4). In contrast, average liver weights (Figure 5) for the control group were significantly greater than those of birds in the 300 ppm CP-31398 treatment group (P < 0.05). The liver weights of birds in the 100 and 200 ppm dosage groups were not statistically different from any other treatment group (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Mean heart weights (g) per bird at 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 18; CP-100, n = 20; CP-200, n = 20; CP-300, n = 20. Values are not statistically different (P > 0.10).

Figure 5.

Mean liver weights (g) per bird at 174 wk of age. Values are means ± SEM: Control, n = 18; CP-100, n = 20; CP-200, n = 20; CP-300, n = 20. Means with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The domestic hen is the only animal model that, after 2 yr of age, presents a high incidence of spontaneous ovarian cancer and is an ideal model for human ovarian cancer because it is an excellent approximation of a premenopausal woman (Zhuge et al., 2009; Fathalla, 2013). After 2 yr of nearly continuous, almost daily ovulation, the hen has undergone a comparable number of ovulations to a woman approaching menopause (Giles et al., 2006). At these late reproductive stages, both the woman and the hen are at a greater risk of developing ovarian malignancies.

Ovarian epithelial carcinomas are thought to arise from mutations in the TP53 gene, which encodes the p53 tumor suppressor protein. p53 functions to prevent the development of cancers by regulating the cell cycle and preventing gene mutations. CP-31398 is a p53 rescue compound that has the potential to be used to prevent ovarian cancer by stabilizing p53 expression and function (Foster et al., 1999). Therefore, CP-31398 was expected to provide a protective effect when fed to laying hens. In the current study, 44.4% of control hens developed ovarian or oviductal cancer compared to 13.19% of those in the high dose group (Table 5). Likewise, 2% of birds fed zero ppm CP, 6% of the 100 ppm hens, 1% of the 200 ppm hens, and 1% of the 300 ppm hens were classified as having ovarian cancer limited to the ovary, suggesting a protective effect for those birds receiving higher levels of the chemopreventive compound.

Egg production, body weight, and feed consumption also were affected by CP-31398 intake (Figures 1–3). Ovulation rates normally decrease as the hen ages; however, CP-31398 treatment at the 200 ppm and 300 ppm led to an accelerated decline of egg production. The MDT and HDT groups experienced a significant decrease in weekly egg production by the third month of the chemopreventive trial. The control and LDT groups also had lower production over the trial, but at a much slower rate than the higher dose treatment groups. Previous studies have speculated that the number of ovulations that a hen experiences over a lifetime may be associated with the risk of ovarian cancer (Fathalla, 1971). A sexually mature commercial laying hen produces an average of 6 eggs per week. At the beginning of the chemopreventive trial, the birds were 79 wk old and completed approximately 500 ovulations. Over the duration of the 95-week trial, the control and low dose treatment groups underwent approximately 320 ovulations, totaling to at least 820 ovulations over 4 years. In contrast, the MDT and HDT groups had only approximately 120 additional ovulations, yielding 620 in total. The incessant ovulation hypothesis suggests that in the hen a substantial number of ovulations may cause enough damage to the ovarian surface epithelia to induce ovarian cancer. If incessant ovulation causes the ovarian neoplasms, the data suggests that the amount of damage necessary to induce mutations within the ovarian surface epithelium occurs after approximately 620 ovulations.

While incessant ovulation is a seemingly plausible hypothesis, it is not entirely supported by the current data. It is possible that the decreased egg production within the moderate and high dose treatment groups was not responsible for the lower incidence of ovarian cancer in those groups, but rather that CP-31398 had a protective effect on the ovary, repairing ovulation-induced mitotic damage to the ovarian surface epithelium. The incessant ovulation hypothesis suggests that the reduced number of ovulations in the moderate and high dose treatment groups lowers the risk of ovarian neoplasm development, due to less ovarian surface epithelium damage. If repeated damage to ovarian tissue at ovulation events were to cause ovarian malignancies, the stress to the ovarian surface epithelium over the course of the 1.5 years and 500 ovulations prior to the initiation of the study should have caused a sufficient amount of damage to trigger the development of any mutations and adenocarcinomas. Despite continued ovulations throughout the study, some hens in all treatment groups never developed ovarian adenocarcinomas. The preservation of the ovarian surface epithelium through as many as 620 to 820 ovulations does not support the incessant ovulation hypothesis, and suggests an underlying protective effect by CP-31398.

As ovulations and egg production decreased in the higher dosage treatment groups, there was a decreased metabolic requirement, and therefore a lower consumption of feed. Although most of the birds had lower feed intake, there were no consistently significant effects on body weight. Maintenance of body weight despite reduced feed intake indicates that the hens did not have complete ovarian regression and simply halted ovulation. At 126 wk of age, 11 mo into the 23-month trial, the moderate and high dose treatment groups had 30% lower feed intake than the control and low dose treatment groups. By 174 wk, all groups treated with CP-31398 maintained the same daily feed consumption, 25% lower than control birds. Although decreased feed consumption would affect the amount of CP-31398 being ingested, the differences in CP-31398 intake were not biologically significant and were accompanied by a reduction in tumor incidence among the birds treated with 200 and 300 ppm CP-31398. Individual dosing, rather than ad libitum feeding within a small group, as done in a rat and dog study performed by Johnson et al. (2011), could control for differences in drug intake. While individual dosing is not practical in the current study, it could be considered in future studies focusing on the clinical applications of CP-31398 for human ovarian cancer prevention.

Along with an initial decrease in egg production, some hepatotoxicity in the birds first treated with 400 ppm CP-31398 (HDT) was observed based upon observed liver hemorrhage found at necropsy. The maximum tolerated dose of a drug is defined as being the highest dose that causes no external signs of toxicity, reduced animal lifespan, mortality, and no more than 10% loss of body weight after chronic administration (Rao et al., 2008). In the rat and dog toxicity study previously described, the animals were given daily oral gavages of CP-31398 for 28 d to investigate the short-term effects of CP-31398 exposure (Johnson et al., 2011). Rats were administered zero, 40, 80, or 160 mg/kg/d of the drug, and dogs were given zero, 10, 20, or 40 mg/kg/day. In those studies, both rats and dogs in the highest dosage treatment groups (160 mg/kg/d, and 40 mg/kg/d, respectively) experienced physiological stress, emesis, weight loss, severe hepatic coagulation necrosis, or even death. Because animals receiving 100 ppm and 200 ppm of CP-31398 did not show the same hepatotoxicity and clinical evidence of stress as the high dosage groups, they were considered to be within the maximum tolerated dosage. It was suggested that sub-chronic CP-31398 hepatotoxicity is reversible in rats and dogs, but in the present study, the significantly lower liver weights of hens in the high dose treatment group suggests that there may have been some residual hepatic damage as a consequence of treatment with 400 ppm CP-31398 early in the study (Johnson et al., 2011). It is also possible that the liver damage resulted from long-term treatment with 300 ppm CP-31398. Unlike the liver, the heart was not significantly affected by CP-31398, indicating no signs of cardiac pathology. Due to varying reports of maximum tolerated dose between species, a proper dose-response toxicity study would need to be performed, separately, to accurately determine the maximum tolerated dose in the hen.

The overriding objective of the chemopreventive trial was to evaluate the influence of CP-31398 supplementation on the incidence of epithelial ovarian carcinoma in the commercial laying hen. Not only do the control and low dose treatment groups have higher incidences of reproductive malignancies, but they also contain a greater percentage of birds with high-grade adenocarcinomas, compared to the moderate and high dose treatment groups.

Oviductal malignancies are an aggressive cancer that may quickly implant on adjacent organs, often making it difficult to determine the origin of the primary adenocarcinoma (Fredrickson, 1987). Classifying the tumors using histopathology alone does not differentiate between ovarian and oviductal cell origins. Ovalbumin, a protein produced by the oviduct, has previously been considered a possible marker for distinguishing between oviductal and ovarian adenocarcinomas (Haritani et al., 1984). In the present study, ovalbumin was found in all ovarian adenocarcinoma samples, regardless of any oviductal involvement, dismissing the ovalbumin protein as a determinate of adenocarcinoma origin. The presence of ovalbumin could be due to dedifferentiation of ovarian tumor cells to mullerian duct-like epithelia, which is a pattern seen in human ovarian tumors (Haritani et al., 1984).

There are three epithelial cancer classifications that are derived from the mullerian duct epithelia in the woman, including fallopian tube-like (serous tumors), endometrium-like (endometrioid), and endocervical-like (mucinous) adenocarcinomas. Over 80% of all human epithelial ovarian neoplasms are considered to be serous adenocarcinomas (Auersperg et al., 2001), heightening the controversy over the origins of ovarian cancer. The gross pathology of mortalities in the present study reveals a difference in the effect of CP-31398 on the ovary vs. the oviduct. The significantly lower incidence of reproductive cancer mortalities in the MDT and HDT groups compared to the C and LDT groups demonstrates a protective effect by CP-31398. Treated birds had a significantly lower rate of ovarian related adenocarcinomas, but no difference was found with oviductal cancers alone. A substantial and significantly lower incidence of classes 3 and 4 ovarian and oviductal metastasized cancers, as well as in class 7 ovarian metastasized cancer (with no oviductal involvement) was found among the moderate and high dose treatment groups. Taken together, the results suggest that CP-31398 demonstrates a protective effect on the ovary, but not on the oviduct.

If CP-31398 specifically targets the ovary, it is a potential pharmacological treatment for the prevention of ovarian cancer through the stabilization of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. The hen serves as an excellent model of the spontaneous development of epithelial ovarian carcinoma as it applies to human ovarian cancer research. This trial demonstrates that the p53 rescue compound CP-31398 can be used as a means of ovarian protection in the adult hen, and may eventually be an applicable cancer prevention treatment for women. More extensive research on the chemopreventive effects of CP-31398 will be necessary to allow for the eventual transition of the compound into clinical use.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at PSCIEN online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Ashwell, Shelly Nolin, Rebecca Wysocky, and Vickie Hedgpeth for technical assistance with tissue sampling. We would also like to thank Jason Osborne for assistance with statistical analysis. Finally, we thank Patrick Marshall, Joshua Fisher, and the technicians at Piedmont Research Station for outstanding animal care and assistance with data collection. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Support provided under contract number 1-NO1-CN43302 from the National Cancer Institute to P. E. Mozdziak, K. Anderson, and J. N. Petitte.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 1: Ingredients and composition of maintenance feed

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 2: Histopathological analysis of samples collected at final necropsy by treatment group

Supplementary data are available at PSCIEN online.

REFERENCES

- American Cancer Society 2013. Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. Atlanta Am. Cancer Soc. [Google Scholar]

- Auersperg N., Wong A. S., Choi K. C., Kang S. K., Leung P. C.. 2001. Ovarian surface epithelium: Biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr. Rev. 22:255–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua A., Bitterman P., Abramowicz J. S., Dirks A. L., Bahr J. M., Hales D. B., Bradaric M. J., Edassery S. L., Rotmensch J., Luborsky J. L.. 2009. Histopathology of ovarian tumors in laying hens: A preclinical model of human ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 19:531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver D. K., Barnes H. J., Anderson K. E., Petitte J. N., Whitaker R., Berchuck A., Rodriguez G. C.. 2011. Reduction of ovarian and oviductal cancers in calorie-restricted laying chickens. Cancer Prev. Res. 4:562–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demma M. J., Wong S., Maxwell E., Dasmahapatra B.. 2004. CP-31398 restores DNA-binding activity to mutant p53 in vitro but does not affect p53 homologs p63 and p73. J. Biol. Chem. 279:45887–45896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathalla M. F. 1971. Incessant ovulation–A factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet. 2:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathalla M. F. 2013. Incessant ovulation and ovarian cancer - A hypothesis re-visited. Facts, views Vis. ObGyn. 5:292–297Available athttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24753957 (accessed 30 August 2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster B. A., Coffey H. A., Morin M. J., Rastinejad F.. 1999. Pharmacological rescue of mutant p53 conformation and function. Science. 286:2507–2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson T. N. 1987. Ovarian tumors of the hen. Environ. Health Perspect. 73:35–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles J. R., Olson L. M., Johnson P. A.. 2006. Characterization of ovarian surface epithelial cells from the hen: A unique model for ovarian cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 231:1718–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim A. A., Barry C. P., Barnes H. J., Anderson K. E., Petitte J., Whitaker R., Lancaster J. M., Wenham R. M., Carver D. K., Turbov J., Berchuck A., Kopelovich L., Rodriguez G. C.. 2009. Ovarian adenocarcinomas in the laying hen and women share similar alterations in p53, ras, and HER-2/neu. Cancer Prev. Res. 2:114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haritani M., Kajigaya H., Akashi T., Kamemura M., Tanahara N., Umeda M., Sugiyama M., Isoda M., Kato C.. 1984. A study on the origin of adenocarcinoma in fowls using immunohistological technique. Avian Dis. 28:1130–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris E. A., Fletcher O. J., Anderson K. E., Petitte J. N., Kopelovich L., Mozdziak P. E.. 2014. Epithelial cell tumors of the hen reproductive tract. Avian Dis. 58:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunn J., Rodriguez G. C.. 2012. Ovarian cancer: Etiology, risk factors, and epidemiology. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 55:3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., Murray T., Xu J., Thun M. J.. 2007. Cancer statistics. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 57:43–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W. D., Muzzio M., Detrisac C. J., Kapetanovic I. M., Kopelovich L., McCormick D. L.. 2011. Subchronic oral toxicity and metabolite profiling of the p53 stabilizing agent, CP-31398, in rats and dogs. Toxicology. 289:141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman R. J., Shih I.-M.. 2010. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: A proposed unifying theory. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 34:433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K. H., Yates M. S., Mok S. C.. 2009. The monkey, the hen, and the mouse: Models to advance ovarian cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Prev. Res. 2:773–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. V, Swamy M. V, Patlolla J. M. R., Kopelovich L.. 2008. Suppression of familial adenomatous polyposis by CP-31398, a TP53 modulator, in APCmin/+ mice. Cancer Res. 68:7670–7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez G. C., Barnes H. J., Anderson K. E., Whitaker R. S., Berchuck A., Petitte J. N., Lancaster J. M., Wenham R. M., Turbov J. M., Day R., Maxwell G. L., Carver D. K.. 2013. Evidence of a chemopreventive effect of progestin unrelated to ovulation on reproductive tract cancers in the egg-laying hen. Cancer Prev. Res. 6:1283–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treviño L. S., Buckles E. L., Johnson P. A.. 2012. Oral contraceptives decrease the prevalence of ovarian cancer in the hen. Cancer Prev. Res. 5:343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuge Y., Lagman J. A. J., Ansenberger K., Mahon C. J., Daikoku T., Dey S. K., Bahr J. M., Hales D. B.. 2009. CYP1B1 expression in ovarian cancer in the laying hen Gallusdomesticus. Gynecol. Oncol. 112:171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data are available at PSCIEN online.