Abstract

During the last decades, a large amount of newly described microduplications and microdeletions associated with intellectual disability (ID) and related neuropsychiatric diseases have been discovered. However, due to natural limitations, a significant part of them has not been the focus of multidisciplinary approaches.

Here, we address previously undescribed chromosome 4q21.2q21.3 microduplication for gene prioritization, evaluation of cognitive abilities and estimation of genomic mechanisms for brain dysfunction by molecular cytogenetic (cytogenomic) and gene expression (meta-) analyses as well as for neuropsychological assessment. We showed that duplication at 4q21.2q21.3 is associated with moderate ID, cognitive deficits, developmental delay, language impairment, memory and attention problems, facial dysmorphisms, congenital heart defect and dentinogenesis imperfecta. Gene-expression meta-analysis prioritized the following genes: ENOPH1, AFF1, DSPP, SPARCL1, and SPP1. Furthermore, genotype/phenotype correlations allowed the attribution of each gene gain to each phenotypic feature.

Neuropsychological testing showed visual-perceptual and fine motor skill deficits, reduced attention span, deficits of the nominative function and problems in processing both visual and aural information. Finally, emerging approaches including molecular cytogenetic, bioinformatic (genome/epigenome meta-analysis) and neuropsychological methods are concluded to be required for comprehensive neurological, genetic and neuropsychological descriptions of new genomic rearrangements/diseases associated with ID.

Keywords: Genomic variations, Brain dysfunction, Copy number variations, Intellectual disability, Microduplication, Neuropsychology, Gene prioritization

1. INTRODUCTION

Chromosomal microdeletions and microduplications (genomic rearrangements) are commonly associated with intellectual disability (ID) and related disorders. During the last decade, brain disorders caused by genomic rearrangements have been a major focus of genome research. Nonetheless, numerous rare genomic rearrangements remain undescribed and require, thereby, thorough multidisciplinary evaluations to succeed in providing adequate health care and development of compensatory strategies [1-4]. The latter requires applications of neuropsychological and psychological methods in addition to clinical data, molecular cytogenetic and genome/epigenome analyses [5, 6]. However, multidisciplinary approaches using genomic and (neuro)psychological techniques are occasionally used for these purposes hindering the generation of an integrated view of molecular, cellular, physiological and psychological contributions to genomic disorders.

Here, a duplication of chromosome 4 at 4q21.2q21.3 is described. In the available literature, similar duplications have not been previously reported. Using molecular cytogenetic (high-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization or CGH) and an in silico genomic/epigenomic approach (gene expression meta-analysis) [7-10] along with neuropsychological and psychological techniques, we were able to perform a comprehensive evaluation of the index case, which has provided prioritization of candidate genes for each phenotypic feature and identification of probable molecular pathways associated with brain dysfunction (ID).

In a case with ID and congenital malformations, we applied CGH followed by a bioinformatic (in silico) molecular cytogenetic analysis [8]. Psychological and neuropsychological evaluation was completed using a modified A.R. Luria method, CARS (Childhood Autism Rating Scale), Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) and Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices.

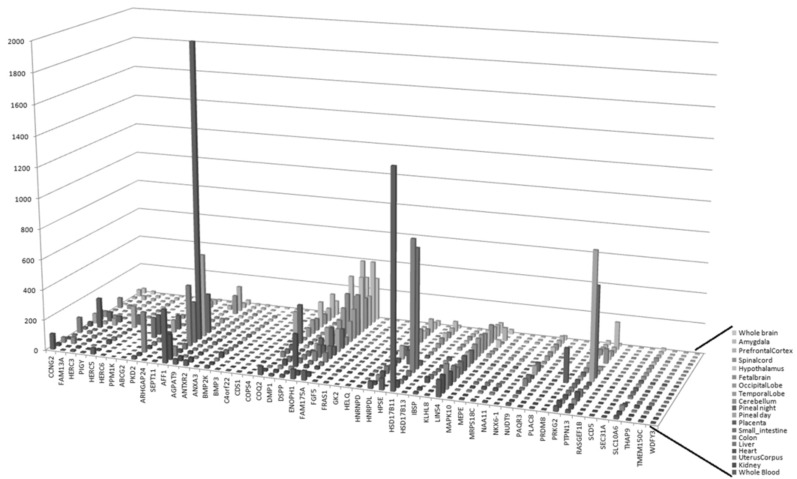

The proposita, an 8-year-old girl, was the first child of non-consanguineous healthy parents with unremarkable family history. Parental age of conception was 24 for both parents. The pregnancy became complicated by pyelonephritis during the first month. Mother suffered from bradycardia during the pregnancy. There was a healthy male sibling. The girl was born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. Birth weight was 2.6 kg (3rd centile); birth length was 48 cm (10-25th centile). She was diagnosed with adrenogenital syndrome, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and hypoxia. At the time of examination, she presented with intellectual disability, developmental delay, cognitive deficits, speech difficulties, memory and attention problems. Her medical history was notable for a congenital heart defect (ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect) and poor sucking reflex. Electroencephalographic examination demonstrated changes in the occipital lobe of the left hemisphere. MRI did not show significant changes. Additionally, she displayed ocular hypertelorism, epicanthus, brachycephaly with frontal bossing, short philtrum and dentinogenesis imperfecta. Cytogenetic analysis revealed 46,XХ,15cenh+ karyotype. Molecular cytogenetic evaluation revealed a duplication of chromosome 4 at 4q21.2-q21.3. The size of the duplication was approximately 9.5 Mb. Gene expression meta-analysis of the duplicated locus of chromosome 4 using genomic and epigenetic databases (for more details about gene prioritization using gene expression profiles see [8, 11, 12]) was applied. The genomic locus contains 125 genes, 53 of which are listed in OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Men), i.e. associated with known monogenic diseases and/or molecular functions. Expression of SPARCL1 was significantly higher in brain areas (mostly prefrontal cortex). The protein encoded by this gene regulates cell division and synaptogenesis [13]. According to gene-expression meta-analysis (Fig. 1, Table 1), additional genes were prioritized: ENOPH1 (hypothalamus, amygdala, parietal lobes of the brain and fetal brain), AFF1 (prefrontal cortex), DSPP (heart), SPP1 (amygdala, prefrontal cortex, spinal cord, hypothalamus, placenta and temporal lobe, dentine). ENOPH1 is involved in the metabolism of methionine and cysteine, AFF1 regulates the development of the central nervous system [14], DSPP encodes two principal proteins of the dentin extracellular matrix of the tooth [15], SPP1 is involved in bone remodeling [16]. Bioinformatic analysis, therefore, have suggested the ID in this duplication as resulted from duplications of SPARCL1 and AFF1 genes. Additional phenotypic features are likely to be associated with increasing the copy number of remaining prioritized genes.

Fig. (1).

Gene-expression meta-analysis for the prioritization of duplicated genes.

Table 1.

Priotirization of candidate genes according to fenotipic features.

| Genes | Function | The Highest Expression Rate Seen in | Suggested Phenotypic Features Caused by a Gene in the Index Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPARCL1 | Involved in the regulation of cell division and synaptogenesis. | Prefrontal cortex. | Intellectual disability. |

| AFF1 | Involved in the development of the central nervous system. | Prefrontal cortex. | Intellectual disability. |

| ENOPH1 | Involved in the metabolism of methionine and cysteine. | Hypothalamus, amygdala, parietal lobes of the brain and fetal brain. | Sex organs abnormalities. |

| DSPP | Encodes two principal proteins of the dentin extracellular matrix of the tooth. | Heart. | Dentinogenesis imperfecta (gene is assosiated with dentinogenesis imperfecta type I). |

| SPP1 | Involved in bone remodeling; expressed in dentine. | Amygdala, prefrontal cortex, spinal cord, hypothalamus, placenta and temporal lobe. | Dentinogenesis imperfecta. |

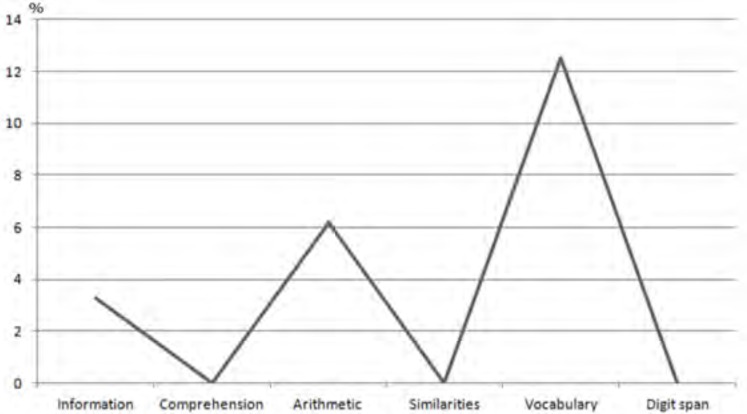

Patient’s intellectual abilities and behavior were assessed using psychological and neuropsychological techniques. Neuropsychological testing (a modified A.R. Luria method) was applied for studying fine motor skills and visual perception. We also utilized CARS (Childhood Autism Rating Scale) to exclude autism and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) [17] and Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices [18] to investigate cognitive abilities. Quantitative evaluation of intellectual abilities, performed via Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices, allowed us to assess the patient’s IQ. The score appeared to be 44 which, according to ICD-10, corresponds to moderate mental retardation. Qualitative analysis of verbal subtests of Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children showed an impairment of auditory-verbal memory, poor vocabulary and troubles in behavior modeling in social situations (Fig. 2). Neuropsychological tests revealed an impaired kinesthetic basis of movement, visuospatial deficits and impaired nominative functions. Difficulties in visual perception and information processing deficits (visual and the auditory type) were also detected using neuropsychological testing. CARS [19] allowed us to conclude the absence of autistic features in the patient. The girl’s parents were informed about the results of the research (Table 2) and given recommendations for consulting a psychologist, occupational therapist and a speech and language pathologist.

Fig. (2).

Wechsler subtests’ results: ordinate values correspond to percent of points scored for correct tests’ responses, which are calculated out of the total possible points for a certain subset.

Table 2.

Psychological methods, results and interpretation.

| Test | Results | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices | The total score is equal to 16, which corresponds to the 25 percentile for the patient’s age group. | The percentage of correct answers is 44% while rates for the 1st and the 2nd grade students is 65% - 100% correct answers. According to ICD-10, 44 points correspond to moderate mental retardation. |

| CARS | The total score is 23,5 points. | It is concluded that the girl does not have autism. |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children | We applied just the verbal subtests. Total score: 15 |

The patient exhibited memory difficulties, reduced vocabulary, troubles in concentration and voluntary attention. Problems in verbal abstract reasoning and simulating (imitating) social behavior were also noted. |

| Neuropsychological tests (a modified Luria method) | We used a set of tests targeted at the examination of visual function, motor function, spatial cognition, receptive speech and expressive speech. | Impaired kinesthetic basis of movement (motor functions), troubles in visual recognition (the girl was unable to name seen objects) and expressive speech, deficits in visual perception, information processing difficulties (visual and the auditory type) were detected. |

According to the available literature, only one case of submicroscopic duplication at similar loci of chromosome 4 was reported. This case represented a de novo microduplication of about 778 Kb in the chromosome region 4q21.22-q21.23, involving 11 genes lacking direct correspondence to the index case in terms of phenotypic outcome and molecular mechanisms [20]. Nevertheless, a deletion encompassing different genomic loci located at chromosome 4q21 resulted in molecular and clinical definitions of the 4q21 microdeletion syndrome [21-26]. Furthermore, a report on microtriplication at 4q21.21-q21.22 unremarkable in the light of present study due to significant phenotypic and molecular differences, has been recently published [27]. Original research presenting the first molecular definition of the 4q21 microdeletion syndrome described 9 children with this syndrome with various microdeletions encompassing different regions of the long arm of chromosome 4: 4q21.1q21.22, 4q21.1q21.23, 4q13.3q21.21, 4q21.21q22.3, 4q21.21q21.22, 4q13.3q21.23, 4q21.21q21.23 [21]. Several patients were found to display common phenotype (Table 3). They presented with frontal bossing, broad forehead, hypertelorism, short philtrum, developmental delay or severe mental retardation, severely delayed speech, neonatal hypotonia and measurement abnormalities. Comparing these results with the present case, it is worth noting that the index patient matches most criteria selected by authors to describe their patients. It is obvious that the data on microdeletions improperly estimates clinical outcomes of microduplications. However, there were no articles found in available literature describing microduplications of exactly the same chromosome 4 regions. Finally, an analysis of phenotypic behaviors in a case of 4q21 microdeletion has shown the applicability of functional assessments in assessing and treating behaviors in known genetic/cytogenomic conditions [24] similar to our results.

Table 3.

Clinical features of patients with microdeletions (according to analyses of selected cases) and microduplication encompassing 4q21 region.

| -- | Present Case | Case 1 [ 21 ] | Case 2 [ 21 ] | Case 4 [ 21 ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 8 | 8 | 13 | 23 |

| Deletion/duplication | Dup 4q21.2q21.3 | Del 4q21.21q22.3 | Del 4q21.21q21.23 | Del 4q21.21q21.23 |

| Size (Mb) | 9±1.5 | 15.1 | 6.3 | 4.5 |

| Facial features | ||||

| a) frontal bossing, broad forehead | + | + | + | + |

| b) hypertelorism | + | - | + | + |

| c) short philtrum | + | + | - | + |

| d) low-set ears | - | + | + | NA |

| Measurement abnormalities | ||||

| a) birth weight | 3rd centile | 25th centile | 50th to 75th centile | <10 centile |

| b) birth length | 10th to 25th centile | 10th to 25th centile | 10th to 25th centile | NA** |

| Developmental delay/mental retardation | ||||

| a) Severely delayed speech | + | + | + | + |

| b) Neonatal hypotonia | - | + | + | + |

**NA – not assessable.

CONCLUSION

In a series of our previous analytical articles dedicated to molecular cytogenomics and its diagnostic applications [3, 28-31], it is shown that high-resolution molecular cytogenetic techniques do require a number of additional approaches and “add-ons” (i.e. somatic genetic and bioinformatics or neuropsychological methods), which are able to increase the diagnostic yield and provide an opportunity for therapeutic interventions [8, 10, 30]. This idea has been lately supported in cytogenomic analyses of somatic mosaicism and genomic instability leading to brain disorders including ID [31-33]. Furthermore, several studies have shown successful therapeutic interventions based on molecular cytogenetomic analysis complemented with advanced in silico molecular cytogenetic (bioinformatics) technologies and, in parts, with clinical and psychological analyses for proper genotype-phenotype correlations [10, 30, 34]. Accordingly, multidisciplinary approaches provide specialists with all available information for adequate evaluation and compensatory strategies. To this end, one can conclude current molecular cytogenetic/cytogenomic, bioinformatic and psychological methods to be highly required for the essential assessment of mental disorders caused by genomic pathology.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our article is dedicated to Ilya V Soloviev. Bioinformatic and molecular cytogenetic studies at Mental Health Research Center are supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project #14-15-00411); neuropsychological and related studies at Moscow State University of Psychology and Education are supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project #14-35-00060).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaffer L.G., Bejjani B.A., Torchia B., Kirkpatrick S., Coppinger J., Ballif B.C. The identification of microdeletion syndromes and other chromosome abnormalities: Cytogenetic methods of the past, new technologies for the future. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 2007;145C(4):335–345. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavotinek A.M. Novel microdeletion syndromes detected by chromosome microarrays. Hum. Genet. 2008;124(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Yurov Y.B. Molecular cytogenetics and cytogenomics of brain diseases. Curr. Genomics. 2008;9(7):452–465. doi: 10.2174/138920208786241216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson C.T., Marques-Bonet T., Sharp A.J., Mefford H.C. The genetics of microdeletion and microduplication syndromes: An update. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2014;15:215–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153408. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalev S.A., Hall J.G. Behavioral pattern profile: A tool for the description of behavior to be used in the genetics clinic. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;128A(4):389–395. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martens M.A., Wilson S.J., Reutens D.C. Research review: Williams syndrome: A critical review of the cognitive, behavioral, and neuroanatomical phenotype. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008;49(6):576–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Kurinnaia O.S., Zelenova M.A., Silvanovich A.P., Yurov Y.B. Molecular karyotyping by array CGH in a Russian cohort of children with intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy and congenital anomalies. Mol. Cytogenet. 2012;5(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-5-46. https://molecularcytogenetics.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.1186/1755-8166-5-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Yurov Y.B. In silico molecular cytogenetics: A bioinformatic approach to prioritization of candidate genes and copy number variations for basic and clinical genome research. Mol. Cytogenet. 2014;7(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13039-014-0098-z. https://molecularcytogenetics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13039-014-0098-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Korostelev S.A., Zelenova M.A., Yurov Y.B. Long contiguous stretches of homozygosity spanning shortly the imprinted loci are associated with intellectual disability, autism and/or epilepsy. Mol. Cytogenet. 2015;8:77. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0182-z. https://molecularcytogenetics.biomedcentral.com/articles/ 10.1186/s13039-015-0182-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Voinova V.Y., Yurov Y.B. 3p22.1p21.31 microdeletion identifies CCK as Asperger syndrome candidate gene and shows the way for therapeutic strategies in chromosome imbalances. Mol. Cytogenet. 2015;8:82. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0185-9. https://molecularcytogenetics.biomedcentral.com/articles/ 10.1186/s13039-015-0185-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Wieringen W.N., Unger K., Leday G.G., Krijgsman O., de Menezes R.X., Ylstra B., van de Wiel M.A. Matching of array CGH and gene expression microarray features for the purpose of integrative genomic analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-80. https://bmcbioinformatics.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.1186/1471-2105-13-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vorsanova S.G., Iurov I.I., Kurinnaia O.S., Voinova V.I., Iurov I.B. Genomic abnormalities in children with mental retardation and autism: The use of comparative genomic hybridization in situ (HRCGH) and molecular karyotyping with DNA-microchips (array CGH). Zh. Nevrol. Psikhiatr. Im. S. S. Korsakova. 2013;113(8):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H., Widegren E., Wang D.W., Sun X.F. SPARCL1: A potential molecule associated with tumor diagnosis, progression and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2011;32(6):1225–1231. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hein M.Y., Hubner N.C., Poser I., Cox J., Nagaraj N., Toyoda Y., Gak I.A., Weisswange I., Mansfeld J., Buchholz F., Hyman A.A., Mann M. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell. 2015;163(3):712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maciejewska I., Chomik E. Hereditary dentine diseases resulting from mutations in DSPP gene. J. Dent. 2012;40:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.04.004. europepmc.org/abstract/med/22521702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Tanani M.K. Role of osteopontin in cellular signaling and metastatic phenotype. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:4276–4284. doi: 10.2741/3004. www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler D. Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raven J. Uses and abuses of Intelligence. Studies advancing Spearman and Raven’s quest for non-arbitrary metrics. Unionville, New York, USA: Royal Fireworks Press; 2008. The Raven progressive matrices tests: Their theoretical basis and measurement model. pp. 17–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schopler E., Reichler R.J., Renner B.R. The childhood autism rating scale (CARS). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottaviani V., Bartocci A., Pantaleo M., Giglio S., Cecconi M., Verrotti A., Merla G., Stangoni G., Prontera P. Myoclonic astatic epilepsy in a patient with a de novo 4q21.22q21.23 microduplication. Genet. Couns. 2015;26:327–332. europepmc.org/abstract/med/26625664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnet C., Andrieux J., Béri-Dexheimer M., Leheup B., Boute O., Manouvrier S., Delobel B., Copin H., Receveur A., Mathieu M., Thiriez G., Le Caignec C., David A., de Blois M.C., Malan V., Philippe A., Cormier-Daire V., Colleaux L., Flori E., Dollfus H., Pelletier V., Thauvin-Robinet C., Masurel-Paulet A., Faivre L., Tardieu M., Bahi-Buisson N., Callier P., Mugneret F., Edery P., Jonveaux P., Sanlaville D. Microdeletion at chromosome 4q21 defines a new emerging syndrome with marked growth restriction, mental retardation and absent or severely delayed speech. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.071902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dukes-Rimsky L., Guzauskas G.F., Holden K.R., Griggs R., Ladd S., Montoya M.C., DuPont B.R., Srivastava A.K. Microdeletion at 4q21.3 is associated with intellectual disability, dysmorphic facies, hypotonia, and short stature. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155A(9):2146–2153. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strehle E.M., Yu L., Rosenfeld J.A., Donkervoort S., Zhou Y., Chen T.J., Martinez J.E., Fan Y.S., Barbouth D., Zhu H., Vaglio A., Smith R., Stevens C.A., Curry C.J., Ladda R.L., Fan Z.J., Fox J.E., Martin J.A., Abdel-Hamid H.Z., McCracken E.A., McGillivray B.C., Masser-Frye D., Huang T. Genotype-phenotype analysis of 4q deletion syndrome: Proposal of a critical region. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2012;158A(9):2139–2151. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fee A., Noble N., Valdovinos M.G. Functional analysis of phenotypic behaviors of a 5-year-old male with novel 4q21 microdeletion. J. Peditr. Neuropsychol. 2015;1(1-4):36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komlósi K., Duga B., Hadzsiev K., Czakó M., Kosztolányi G., Fogarasi A., Melegh B. Phenotypic variability in a Hungarian patient with the 4q21 microdeletion syndrome. Mol. Cytogenet. 2015;8:16. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0118-7. https://molecularcytogenetics.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.../s13039-015-0118-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X., Chen X., Wu B., Soler I.M., Chen S., Shen Y. Further defining the critical genes for the 4q21 microdeletion disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2017;173(1):120–125. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lebedev I.N., Nazarenko L.P., Skryabin N.A., Babushkina N.P., Kashevarova A.A. A de novo microtriplication at 4q21.21-q21.22 in a patient with a vascular malignant hemangioma, elongated sigmoid colon, developmental delay, and absence of speech. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2016;170(8):2089–2096. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Yurov Y.B. Chromosomal variation in mammalian neuronal cells: Known facts and attractive hypotheses. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2006;249:143–191. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)49003-3. europepmc.org/abstract/med/16697283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vorsanova S.G., Yurov Y.B., Soloviev I.V., Iourov I.Y. Molecular cytogenetic diagnosis and somatic genome variations. Curr. Genomics. 2010;11(6):440–446. doi: 10.2174/138920210793176010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Yurov Y.B. Single cell genomics of the brain: Focus on neuronal diversity and neuropsychiatric diseases. Curr. Genomics. 2012;13(6):477–488. doi: 10.2174/138920212802510439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Yurov Y.B. Somatic cell genomics of brain disorders: A new opportunity to clarify genetic-environmental interactions. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2013;139:181–188. doi: 10.1159/000347053. https://www.karger.com/Article/ PDF/347053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yurov Y.B., Vorsanova S.G., Iourov I.Y., Demidova I.A., Beresheva A.K., Kravetz V.S., Monakhov V.V., Kolotii A.D., Voinova-Ulas V.Y., Gorbachevskaya N.L. Unexplained autism is frequently associated with low-level mosaic aneuploidy. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44(8):521–525. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.049312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iourov I.Y., Vorsanova S.G., Liehr T., Kolotii A.D., Yurov Y.B. Increased chromosome instability dramatically disrupts neural genome integrity and mediates cerebellar degeneration in the ataxia-telangiectasia brain. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18(14):2656–2669. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abunimer A.N., Salazar J., Noursi D.P., Abu-Asab M.S. A systems biology interpretation of array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) data through phylogenetics. OMICS. 2016;20(3):169–179. doi: 10.1089/omi.2015.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]