Summary

We observed an independent association between isoniazid resistance and death following the first 60 days of therapy for 324 patients with culture-confirmed tuberculous meningitis in New York City, with 10 years of follow-up.

Keywords: tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis, drug resistance, multidrug resistance, treatment outcome

Abstract

Background.

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most devastating clinical presentation of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; delayed initiation of effective antituberculosis therapy is associated with poor treatment outcomes. Our objective was to determine the relationship between drug resistance and 10-year mortality among patients with TBM.

Methods.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 324 patients with culture-confirmed TBM, susceptibility results reported for isoniazid and rifampin, and initiation of at least 2 antituberculosis drugs, reported to the tuberculosis registry in New York City between 1 January 1992 and 31 December 2001. Date of death was ascertained by matching the tuberculosis registry with death certificate data for 1992–2012 from the New York Office of Vital Statistics. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was ascertained by medical records review, matching with the New York City HIV Surveillance registry, and review of cause of death.

Results.

Among 257 TBM patients without rifampin-resistant isolates, isoniazid resistance was associated with mortality after the first 60 days of treatment when controlling for age and HIV infection (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.94 [95% confidence interval, 1.08–3.94]). Death occurred before completion of antituberculosis therapy in 63 of 67 TBM patients (94%) with rifampin-resistant disease.

Conclusions.

Among patients with culture-confirmed TBM, we observed rapid early mortality in patients with rifampin-resistant isolates, and an independent association between isoniazid-resistant isolates and death after 60 days of therapy. These findings support the continued evaluation of rapid diagnostic techniques and the empiric addition of second-line drugs for patients with clinically suspected drug-resistant TBM.

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most devastating presentation of disease with Mycobacterium tuberculosis [1], and has emerged as a leading cause of bacterial meningitis in many areas due to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic [2]. Diagnostic delays are common, and the resulting delay in the initiation of effective antituberculosis therapy leads to inferior treatment outcomes [3]. Historically, guidelines for the treatment of TBM are based on pulmonary tuberculosis clinical trials [4], but recent trials have explored alternate regimens for TBM. An intensified treatment regimen for TBM that included fluoroquinolones and increased intravenous rifampin dosing was shown to improve clinical outcomes among Indonesian TBM patients [5], and rifampin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were increased several-fold with intravenous therapy over standard therapy. However, a larger randomized trial of increased oral rifampin therapy, combined with a fluoroquinolone, among TBM patients in Vietnam failed to demonstrate a benefit [6].

The management of drug-resistant TBM is challenging, given the time required to obtain drug susceptibilities, the paucity of data on the effectiveness of second-line antituberculosis drugs for the treatment of meningitis, and limited data regarding the utility of rapid molecular diagnostic techniques for the detection of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis in samples of CSF [7]. Isoniazid resistance is the most common form of drug-resistant tuberculosis worldwide, and studies from the United States [8] and Vietnam [9] have demonstrated an increased risk of death among TBM patients with isoniazid-resistant disease. The role of isoniazid in successful therapy of TBM may be due to its bactericidal activity and penetration into the central nervous system (CNS) [10]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) TBM, defined as infection with M. tuberculosis strains resistant to both isoniazid and rifampin, has a mortality rate approaching 100% [9, 11, 12].

Neurologic injury is the hallmark of TBM pathogenesis [13], and many survivors suffer from residual motor and cognitive impairments [14–17]. The long-term consequences of neurologic disability following TBM remain poorly understood. Survivors of TBM with severe cognitive or motor disabilities may remain at higher risk of death from other causes [18], and consequently the assessment of mortality during antituberculosis therapy may fail to capture the total mortality burden of TBM. To date, no longitudinal studies have examined the relationship between initial drug resistance patterns and the long-term mortality of TBM patients beyond the completion of therapy. We sought to determine the relationship between the initial drug resistance patterns and long-term mortality among TBM patients in New York City, a setting with intensive case-finding resources, regular performance of drug susceptibility testing, and access to second-line antituberculosis drugs.

METHODS

Setting and Population

We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients with TBM reported to the New York City tuberculosis registry between 1 January 1992 and 31 December 2001. The registry included information collected from patient interviews and medical record reviews using standard data collection instruments. Patients with TBM were identified by the presence of a positive culture of CSF or CNS tissue (brain or meninges) for M. tuberculosis, which was consistent with the clinical research definition of a confirmed case of TBM [19]. The study population was limited to TBM patients whose isolates had known drug susceptibility results for isoniazid and rifampin, in order to examine the relationship of resistance to these drugs with long-term mortality.

Data Collection

All patients with tuberculosis were actively followed by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) from the time of reporting until completion of therapy, transfer out of New York City, loss to follow-up prior to treatment completion, or death. We reviewed inpatient medical records, where available, with additional TBM-specific information abstracted by trained Bureau of Tuberculosis Control staff. The presence of HIV infection was ascertained by review of medical records, and additionally from a match with the New York City HIV Surveillance Registry.

The drug resistance pattern was defined by the earliest drug susceptibility testing results from a CNS site (either CSF or tissue culture). In cases where drug susceptibility testing results from the CNS site were unavailable, drug susceptibility results from cultures coincident with the diagnosis of TBM were substituted (eg, drug susceptibility testing of a sputum culture closest to the time the positive CSF culture was obtained). Susceptibility testing was performed by the BACTEC radiometric method (Becton Dickinson and Co, Sparks, New York) for isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and streptomycin for most isolates [20], and with standard proportion method with Middlebrook 7H10 media for both first- and second-line drugs for all isolates [21]. Most of these tests were conducted at 2 reference laboratories, the New York City DOHMH and the New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center, Albany.

Date of death was ascertained by matching the TBM patient demographic data found in the tuberculosis registry with death certificate data for 1992–2012 from the New York City Office of Vital Statistics (OVS), which maintains data collected from death certificates issued in New York City. A probabilistic match was performed between the tuberculosis registry and the OVS death records. We also reviewed the cause of death to identify additional TBM patients with HIV coinfection who had not been captured by either medical records review or the New York City HIV Surveillance Registry matching. In these instances, we reasoned that HIV coinfection was likely present at the time of TBM diagnosis, given the causal relationship between HIV and development of CNS infection with M. tuberculosis [22].

Statistical Analysis

We categorized drug resistance patterns as susceptible to both isoniazid and rifampin, resistant to isoniazid but not resistant to rifampin, resistant to rifampin but not resistant to isoniazid, and MDR. This classification scheme did not rule out resistance to other antituberculosis drugs (eg, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, or streptomycin).

Follow-up time was calculated from the date of the first positive CNS culture, which we defined as the date of TBM diagnosis, until either the date of death or censoring. We began follow-up time at the date of TBM diagnosis rather than the date of treatment initiation to prevent the introduction of immortal time bias among TBM patients who initiated antituberculosis therapy before the TBM diagnosis was established. Immortal time refers to the period of time when, by design, death cannot occur in the study population [23]. In this study, a TBM patient death can only occur after the diagnosis with TBM. Temporal trends were examined with the nonparametric extension of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Right censoring was performed after 10 years of follow-up time for all patients not known to have died by that time.

We constructed Kaplan-Meier survival curves to examine time to death or censoring, and then stratified according to initial drug resistance patterns and HIV status. As the receipt of antiretroviral drugs was not captured in this study, we further stratified HIV status according to year of diagnosis of TBM (before or after 1 January 1997), corresponding to the availability of protease inhibitors for the treatment of HIV infection [24, 25]. Comparison of survival curves was performed with the log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to determine the independent association of initial drug resistance patterns with long-term survival. The models were adjusted for potential confounding factors, including age, race, sex, HIV infection, country of origin, homelessness (ever), concomitant pulmonary disease, and prior tuberculosis treatment. Variables remained in the multivariate model if the inclusion led to >15% change in the hazard ratio (HR) for the drug resistance pattern of interest [26]. HIV infection and age were included regardless of effect, based on clinical reasoning. The proportional hazard assumption was examined via interaction between the covariate of interest and follow-up time, and by examination of scaled Schoenfeld residuals [27].

To compare the long-term survival of TBM patients who complete treatment with that of a demographically comparable population without TBM, we estimated a standardized mortality ratio (SMR), as described by Finkelstein et al [28]. Actuarial tables in the National Vital Statistics Report provide rates of death in the population according to age, race, and sex. The SMR is determined from the ratio of the observed deaths in the study group to the number of expected deaths in a demographically matched population, with the P value calculated by the 1-sample log-rank test.

Categorical data were compared using Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact 2-tailed test, where appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13 software (StataCorp 2013, College Station, Texas), and figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California). A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York City DOHMH.

RESULTS

Between 1 January 1992 and 31 December 2001, there were 18339 patients with culture-confirmed tuberculosis reported in New York City, and 376 (2.1%) unique patients had culture-confirmed TBM. Drug susceptibility test results for isoniazid and rifampin were available for 360 (95.7%) patients. Among these 360 patients, 36 (10.0%) died before initiating antituberculosis therapy, a median of 7 days (interquartile range [IQR], 2–12 days) following the collection of the specimen with the first positive CNS culture. None of the specimens were collected postmortem. All of the remaining 324 TBM patients initiated treatment with ≥2 antituberculosis drugs, comprising the study population (Supplementary Figure 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1, stratified by drug resistance patterns. Patients with MDR TBM were more likely to be US born, HIV infected, and to have pulmonary tuberculosis. The proportion of TBM patients infected with HIV decreased during the study period (P < .001), as shown in Figure 1. Among 204 TBM patients (63.0%) who were identified as infected with HIV, the diagnosis was established by medical records review for 185 patients (90.7%). Additional diagnoses of HIV infection were established for 7 patients (3.4%) by matching with the Bureau of HIV AIDS registry, and for 12 patients (5.9%) by review of the OVS death records.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Culture-Confirmed Tuberculous Meningitis in New York City, 1992–2001 (N = 324)

| Characteristic | INH-S, RIF-S (n = 225) |

INH-R, RIF-S (n = 32) |

INH-S, RIF-R (n = 6) |

MDR (n = 61) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | .158 | ||||

| <19 | 13 (5.8) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| 19–45 | 142 (63.1) | 24 (75) | 5 (83) | 50 (82) | |

| 46–65 | 47 (20.9) | 5 (16) | 1 (17) | 10 (16) | |

| ≥66 | 23 (10.2) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Sex | .51 | ||||

| Male | 155 (68.9) | 25 (78) | 5 (83) | 46 (75) | |

| Female | 70 (31.1) | 7 (22) | 1 (17) | 15 (25) | |

| Race | .29 | ||||

| Asian | 20 (8.9) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic | 66 (29.3) | 11 (34) | 1 (17) | 20 (33) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 120 (53.3) | 17 (53) | 5 (83) | 32 (52) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 19 (8.4) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 9 (15) | |

| US born | 145 (64.4) | 22 (69) | 6 (100) | 49 (80) | .038 |

| Homelessness history | 28 (12.4) | 4 (13) | 0 (0) | 8 (13) | .83 |

| HIV infection | 123 (54.7) | 18 (56) | 6 (100) | 57 (93) | <.001 |

| Previous history of TB | 6 (2.7) | 6 (19) | 1 (17) | 4 (7) | .001 |

| Any pulmonary disease | 69 (30.7) | 13 (41) | 3 (50) | 37 (61) | <.001 |

| CSF smear positivea | 14 (7) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 7 (11) | .150 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INH-R, isoniazid resistant; INH-S, isoniazid sensitive; MDR, multidrug resistant; RIF-R, rifampin resistant; RIF-S, rifampin sensitive; TB, tuberculosis.

Result of CSF smear not available in 49 patients.

Figure 1.

Annual number of patients with culture-confirmed tuberculous meningitis in New York City, 1992–2001 (N = 324), according to HIV status and isoniazid susceptibility. Year of diagnosis corresponds to the date that the first positive cerebrospinal fluid culture was collected. *Nonparametric test for trend in the proportion of tuberculous meningitis patients coinfected with HIV. Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INH-R, isoniazid resistant; INH-S, isoniazid sensitive; TBM, tuberculous meningitis.

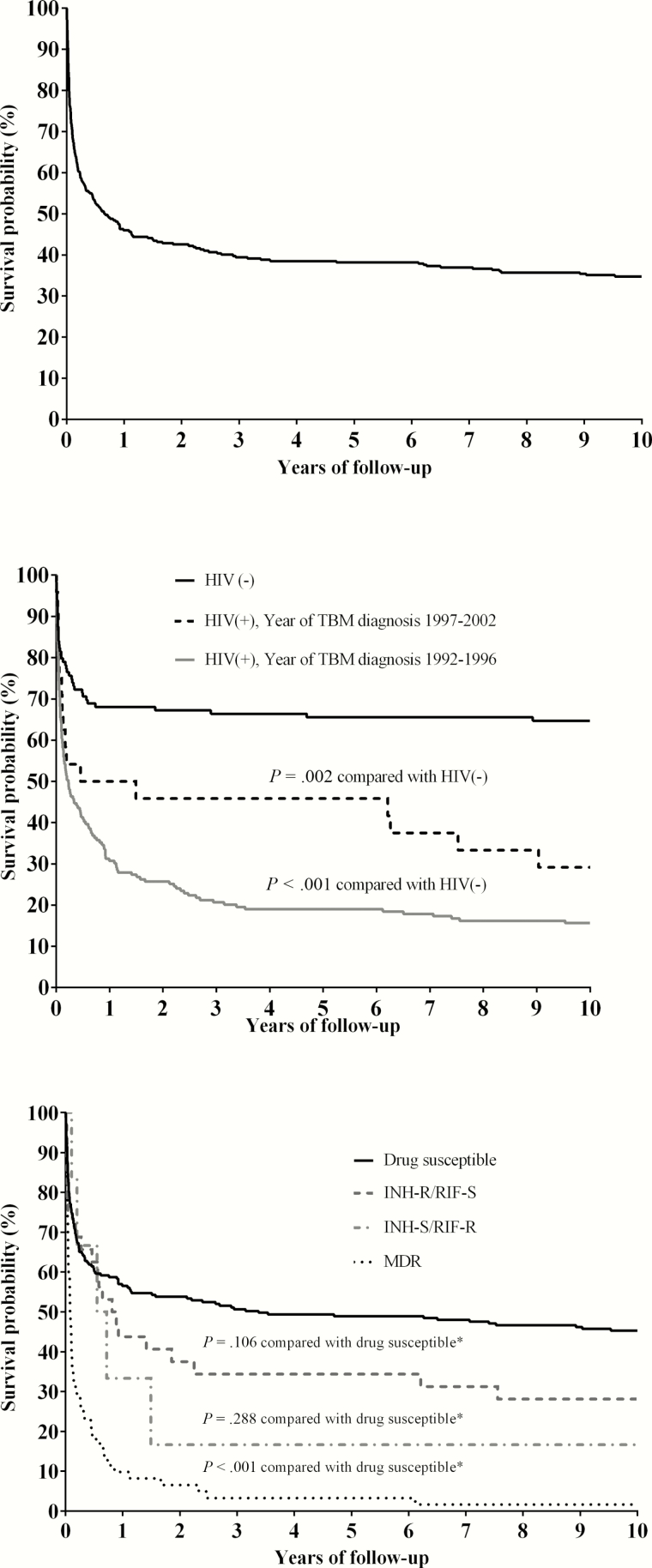

The 324 TBM patients initiating antituberculosis therapy had a median survival of 243 days (Figure 2A). One hundred eighty-three of 324 patients (56.5%) died before completing antituberculosis therapy, after a median survival of 23 days (IQR, 0–150 days). Among 117 TBM patients (36.1%) who completed antituberculosis therapy, the median treatment duration was 335 days (IQR, 308–399 days) from the date of diagnosis of TBM. The remaining 24 patients (7.4%) were lost to follow-up prior to treatment completion, after a median follow-up time of 215 days (IQR, 121–320 days).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with culture-confirmed tuberculous meningitis, susceptibility reported for isoniazid and rifampin, initiating antituberculosis treatment with ≥2 drugs. A, Overall. B, Stratified by HIV status. C, Stratified by drug susceptibility patterns. *Statistical comparison of survival curves with log-rank test. Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INH-R, isoniazid resistant; INH-S, isoniazid sensitive; MDR, multidrug resistant; RIF-R, rifampin resistant; RIF-S, rifampin sensitive; TBM, tuberculous meningitis.

Survival curves according to HIV status are shown in Figure 2B, stratified by year of diagnosis (before or after 1 January 1997). Both groups of HIV-infected patients demonstrated decreased survival compared with patients without a known diagnosis of HIV infection (log rank P < .001 before 1 January 1997; P = .002 after 1 January 1997). The difference in survival for HIV-infected patients diagnosed with TBM before and after the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy did not reach statistical significance (P = .091), possibly reflecting smaller numbers of patients within these groups.

Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by drug susceptibility test results are shown in Figure 2C. There were 225 patients without isoniazid- or rifampin-resistant disease, and 102 (45%) died during follow-up. Among 61 patients with MDR TBM, 58 died (95%, log-rank P < .001 compared with drug-susceptible). Among 32 patients with isoniazid-resistant, rifampin-sensitive disease, 18 died (56%; log-rank P = .106 compared with drug-susceptible). Given that HIV infection was present in 57 of 61 TBM patients (93%) with multidrug resistance, and in 100% (6/6) of TBM patients whose isolates had rifampin resistance but isoniazid susceptibility, we were unable to estimate the association between rifampin resistance and mortality independent of the effect of HIV infection. Among all TBM patients with rifampin-resistant isolates, 63 of 67 patients (94%) died before the completion of therapy after a median of 31 days from collection of positive CSF specimen (IQR, 13–115 days), and 60 of these 63 patients (95%) were infected with HIV.

Among 257 TBM patients whose isolates were susceptible to rifampin, HIV infection was found in similar proportions of TBM patients whose isolates were isoniazid susceptible (54.7%) or resistant (56%). All TBM patients with isoniazid-resistant isolates were initially treated with a regimen that included isoniazid. Among the clinical and demographic factors shown in Table 1, HIV status and age were retained in the Cox regression model based on clinical reasoning.

Examination of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for isoniazid-susceptible (rifampin-susceptible) and isoniazid-resistant (rifampin-susceptible) disease (Figure 2C) suggested a violation of the assumption of proportional hazards over time. This violation was confirmed by the scaled Schoenfeld residuals (P = .007). Based on prior work from Vietnam with similar results [9], as well as the tuberculosis control practices that define the intensive phase as the first 60 days of treatment, we fit separate Cox models for the first 60 days following diagnosis, and from 60 days until the date of death or censoring (Table 2). In each of these models, we observed nonsignificant interaction terms for isoniazid resistance and log-transformed follow-up time (P = .97 during the first 60 days; P = .34 from 60 days until censoring), consistent with the assumption of proportional hazards during each of these time periods. An independent association between isoniazid resistance and mortality was observed after the first 60 days (adjusted HR, 1.94 [95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–3.94]). HIV infection was associated with mortality during each time period, whereas an association between advanced age and mortality was only observed during the first 60 days.

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Mortality Among Patients With Culture-Confirmed, Rifampin-Sensitive Tuberculous Meningitis (n = 257)

| Characteristic | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Death During the First 60 d Following Diagnosis (n = 257) |

Death After the First 60 d Following Diagnosis (n = 181) |

|

| Isoniazid resistance | 0.55 (.22–1.38) | 1.94 (1.08–3.50) |

| HIV coinfection | 2.24 (1.22–4.09) | 4.21 (2.32–7.64) |

| Age group, y | ||

| <19 | 0.47 (.06–3.61) | a |

| 19–45 | Reference | Reference |

| 46–65 | 1.99 (1.14–3.49) | 0.83 (.44–1.55) |

| ≥66 | 2.55 (1.08–6.04) | 1.45 (.54–3.87) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

There were no deaths among patients with tuberculous meninigitis aged <19 y beyond 60 d.

Among 117 patients with drug-susceptible isolates who were reported to complete therapy, we compared the Kaplan-Meier survival curves with age- and sex- matched controls from US census data (Figure 3). Compared with the reference population, we did not observe a difference in the SMR for survivors of TBM not known to be infected with HIV (SMR, 0.72 [95% CI, .35–1.50]). In contrast, among TBM patients infected with HIV, we observed an additional mortality burden in the immediate posttreatment time period, which continued throughout follow-up time (SMR, 13.25 [95% CI, 8.57–20.50]).

Figure 3.

Long-term survival of 117 patients with tuberculous meningitis (TBM) who successfully completed therapy, compared with age- and sex-matched population controls. A, Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–uninfected survivors of TBM (n = 65). B, HIV-infected survivors of TBM (n = 52).

We performed a secondary analysis of 16 individuals <19 years of age at diagnosis (median, 4 years [IQR, 1–9.5 years]). Four of 16 (25%) children with TBM died before completing therapy, with 2 of 4 deaths occurring in children with HIV infection. One child was lost to follow-up before treatment completion. Among 11 children who completed therapy for TBM, there were no deaths during the 10-year follow-up period.

We performed 2 sensitivity analyses. First, we measured follow-up time from the date of antituberculosis treatment initiation, rather than the date that the positive CSF culture was collected. In a Cox model that included HIV infection and age, we observed that isoniazid resistance was associated with death after the first 60 days (adjusted HR, 2.09 [95% CI, 1.23–3.55]). Second, we included patients who died before initiating antituberculosis therapy in the Cox model that adjusted for HIV infection and age, and observed a significant association between isoniazid resistance and death after the first 60 days (adjusted HR, 1.94 [95% CI, 1.08–3.50]).

DISCUSSION

In this study of culture-confirmed TBM diagnosed over a 10-year period in New York City, we found that initial drug resistance and HIV infection were powerful predictors of all-cause mortality over a 10-year follow-up period. Among TBM patients who died before completing antituberculosis therapy, most deaths occurred during the first month of treatment. As previously shown in this setting [29], HIV infection was strongly associated with rifampin resistance, and we were unable to estimate the independent associations of HIV infection and rifampin resistance with mortality.

We found that the association of isoniazid resistance and mortality was time-dependent and became significant after the first 60 days of therapy. Given that second-line drugs are typically initiated once susceptibility results are available, it is surprising that the detrimental effect of isoniazid resistance was not evident during the initial phase of treatment. One explanation for this finding is that rifampin autoinduction of systemic clearance leads to declining rifampin CSF concentrations during the intensive phase of treatment [30], which may then unmask the deleterious effect of isoniazid resistance. Isoniazid may also continue to offer benefit to TBM patients with low-level resistance, and the discontinuation of isoniazid in these patients once isoniazid resistance was reported may have led to clinical deterioration. The benefit of isoniazid among patients with low-level isoniazid resistance is currently being evaluated in a prospective clinical trial of pulmonary tuberculosis (AIDS Clinical Trials Group study 5312). Although acquired rifamycin resistance was not observed among TBM patients with isoniazid resistance in this study, baseline isoniazid resistance was associated with the emergence of rifamycin resistance among HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis in India [31]. The absence of an association between isoniazid resistance and early mortality could also reflect the smaller number of patients in this group.

Our study had several limitations. We did not capture deaths if they occurred outside New York City. Adjunctive corticosteroids improve survival of TBM patients [32]. We had limited information regarding the use of corticosteroids for the study population, which precluded our ability to include this factor in the multivariate analysis. We also did not include the stage of disease at the time of presentation, which is an important predictor of survival [1].

In summary, we observed an independent association between isoniazid resistance and death following the first 60 days of therapy for TBM. Among survivors not known to be infected with HIV, with an isolate susceptible to both isoniazid and rifampin, the long-term survival following completion of TBM treatment was similar to that of population controls. These findings support the evaluation of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for suspected TBM, including the rapid assessment of both rifampin and isoniazid resistance using molecular methods [33, 34], phenotypic drug resistance assays that provide a minimum inhibitory concentration (distinguishing between low-level and high-level isoniazid resistance) [35], and intensified initial treatment regimens for patients with suspected drug-resistant TBM.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Lisa Trieu for assistance in data management.

Financial support. C. V. was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number K23AI102639).

Potential conflicts of interest. Authors certify no potential conflicts of interest. The authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12:999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Veltman JA, Bristow CC, Klausner JD. Meningitis in HIV-positive patients in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van TT, Farrar J. Tuberculous meningitis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014; 68:195–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines. 4th ed Available at:http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44165/1/9789241547833_eng.pdf Accessed 7 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruslami R, Ganiem AR, Dian S, et al. Intensified regimen containing rifampin and moxifloxacin for tuberculous meningitis: an open-label, randomized controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heemskerk AD, Nguyen DB, Nguyen THM, et al. Intensified antituberculosis therapy in adults with tuberculous meningitis. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:124–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boyles TH, Thwaites GE. Appropriate use of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in suspected tuberculous meningitis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19:276–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vinnard C, Winston CA, Wileyto EP, Macgregor RR, Bisson GP. Isoniazid resistance and death in patients with tuberculous meningitis: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2010; 341:c4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tho DQ, Török ME, Yen NT, et al. Influence of antituberculosis drug resistance and Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage on outcome in HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:3074–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donald PR. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of antituberculosis agents in adults and children. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2011; 90:279–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel VB, Padayatchi N, Bhigjee AI, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculous meningitis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vinnard C, Winston CA, Wileyto EP, MacGregor RR, Bisson GP. Multidrug resistant tuberculous meningitis in the United States, 1993–2005. J Infect 2011; 63:240–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rock RB, Olin M, Baker CA, Molitor TW, Peterson PK. Central nervous system tuberculosis: pathogenesis and clinical aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008; 21:243–61; table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson NE, Somaratne J, Mason DF, Holland D, Thomas MG. Neurological and systemic complications of tuberculous meningitis and its treatment at Auckland City Hospital, New Zealand. J Clin Neurosci 2010; 17:1114–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiang SS, Khan FA, Milstein MB, et al. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Torok ME, Bang ND, Chau TTH, et al. Dexamethasone and long-term outcomes of tuberculous meningitis in Vietnamese adults and adolescents. PLoS One 2011; 6:e27821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miftode EG, Dorneanu OS, Leca DA, et al. Tuberculous meningitis in children and adults: a 10-year retrospective comparative analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0133477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lauer E, McCallion P. Mortality of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities from select US state disability service systems and medical claims data. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2015; 28:394–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hawkins JE, Wallace R, Jr, Brown BA. Antibacterial susceptibility tests: mycobacteria. In: Balows A, Hausler WJ, Jr, Herrmann K, Isenberg HD, Shadomy HJ, eds. Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1991:1138–52. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kent PT, Kubica GP. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berenguer J, Moreno S, Laguna F, et al. Tuberculous meningitis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:668–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lévesque LE, Hanley JA, Kezouh A, Suissa S. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ 2010; 340:b5087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. King L, Munsiff SS, Ahuja SD. Achieving international targets for tuberculosis treatment success among HIV-positive patients in New York City. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010; 14:1613–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris TG, Li J, Hanna DB, Munsiff SS. Changing sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients, New York City, 1992–2005. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50:1524–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 129:125–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee ET, Go OT. Survival analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health 1997; 18:105–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Finkelstein DM, Muzikansky A, Schoenfeld DA. Comparing survival of a sample to that of a standard population. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95:1434–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Munsiff SS, Joseph S, Ebrahimzadeh A, Frieden TR. Rifampin-monoresistant tuberculosis in New York City, 1993–1994. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25:1465–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smythe W, Khandelwal A, Merle C, et al. A semimechanistic pharmacokinetic-enzyme turnover model for rifampin autoinduction in adult tuberculosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:2091–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Swaminathan S, Narendran G, Venkatesan P, et al. Efficacy of a 6-month versus 9-month intermittent treatment regimen in HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181:743–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thwaites GE, Nguyen DB, Nguyen HD, et al. Dexamethasone for the treatment of tuberculous meningitis in adolescents and adults. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nhu NT, Heemskerk D, Thu do DA, et al. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:226–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gupta R, Thakur R, Gupta P, et al. Evaluation of genotype MTBDRplus line probe assay for early detection of drug resistance in tuberculous meningitis patients in India. J Glob Infect Dis 2015; 7:5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heysell SK, Pholwat S, Mpagama SG, et al. Sensititre MycoTB plate compared to Bactec MGIT 960 for first- and second-line antituberculosis drug susceptibility testing in Tanzania: a call to operationalize MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:7104–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.