We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of botulism treatment. Published studies generally were low quality, but support timely administration of antitoxin and high quality supportive care to reduce mortality.

Keywords: botulism, antitoxin, systematic review

Abstract

Background

Botulism is a rare, potentially severe illness, often fatal if not appropriately treated. Data on treatment are sparse. We systematically evaluated the literature on botulinum antitoxin and other treatments.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review of published articles in PubMed via Medline, Web of Science, Embase, Ovid, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and included all studies that reported on the clinical course and treatment for foodborne botulism. Articles were reviewed by 2 independent reviewers and independently abstracted for treatment type and toxin exposure. We conducted a meta-analysis on the effect of timing of antitoxin administration, antitoxin type, and toxin exposure type.

Results

We identified 235 articles that met the inclusion criteria, published between 1923 and 2016. Study quality was variable. Few (27%) case series reported sufficient data for inclusion in meta-analysis. Reduced mortality was associated with any antitoxin treatment (odds ratio [OR], 0.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], .09–.30) and antitoxin treatment within 48 hours of illness onset (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, .03–.41). Data did not allow assessment of critical care impact, including ventilator support, on survival. Therapeutic agents other than antitoxin offered no clear benefit. Patient characteristics did not predict poor outcomes. We did not identify an interval beyond which antitoxin was not beneficial.

Conclusions

Published studies on botulism treatment are relatively sparse and of low quality. Timely administration of antitoxin reduces mortality; despite appropriate treatment with antitoxin, some patients suffer respiratory failure. Prompt antitoxin administration and meticulous intensive care are essential for optimal outcome.

Botulism is a rare neuroparalytic illness characterized by bilateral cranial nerve palsies and descending paralysis, which may lead to respiratory failure. Disease can be fatal, particularly without treatment. Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) mediates the effects of disease [1, 2]. Foodborne botulism occurs following ingestion of toxin found in contaminated foods; outbreaks occur periodically, and contamination of a widely consumed food could cause many illnesses. BoNT is the most toxic substance by weight known, and various countries with biologic warfare programs have weaponized it as a biological weapon. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classifies BoNT as a category A biological agent [3, 4].

Seven botulism toxin serotypes, A–G, were described between 1919 and 1970. Most human botulism is caused by serotypes A, B, E, and F, but others have pathogenic potential as well. Paralysis induced by BoNT can last weeks to months. In cases in which the respiratory tract or respiratory muscles are impaired, mechanical ventilation is life-saving. Botulinum antitoxins can neutralize circulating botulinum toxin, preventing toxin binding to the neuromuscular junction, but does not reverse existing paralysis. The mainstays of treatment are supportive care and botulinum antitoxin. These measures have been credited with reducing botulism mortality in the United States from >60% in the early 20th century to <5% at present [5]. Additionally, other targeted treatments have been attempted to ameliorate the effects of botulism, such as cathartics and enemas to clear toxin from the gastrointestinal tract, and guanidine and 3,4-diaminopuridine to stimulate acetylcholine release [6].

Equine-source botulism antitoxins of varying valencies (anti-A, anti-B, anti-AB, etc) and neutralizing capacities have been used over the past century. Currently, the sole botulinum antitoxin product licensed for treatment of noninfant botulism in the United States is equine-source botulism antitoxin heptavalent [7]. A human-source antitoxin, botulism immune globulin intravenous (BIG-IV), is licensed in the United States solely for the treatment for infants with botulism type A or type B.

Botulism is rare, with <100 noninfant cases and approximately 100 infant cases reported annually in the United States [8]. Consequently, peer-reviewed studies on the efficacy of botulinum antitoxin are sparse. In nearly a century, only 1 study, involving a retrospective cohort, examined the effectiveness of equine-origin botulinum antitoxin, finding reduced mortality and other measures of severity associated with early treatment [9]. For infant botulism, 1 randomized controlled trial found that use of BIG-IV was associated with reduced duration of mechanical ventilation and hospitalization without reported adverse events [10–13].

A large botulism outbreak, either naturally occurring or intentionally created, may strain resources, and at present, no evidence-based guidance exists to prioritize antitoxin administration. Data-based treatment recommendations are needed to ensure an effective and efficient public health response. We sought to systematically review all published reports and studies on the treatment of foodborne botulism. The questions that guided our systematic review were (1) what benefit should be expected from botulinum antitoxin? (2) Is there a window of time beyond which administration of antitoxin is no longer beneficial? (3) Do any patient demographic or clinical characteristics predict greater benefit from antitoxin administration?

METHODS

This study was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42015024327). Our systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14].

Search Strategy

With the assistance of an expert research librarian, we queried PubMed via Medline, Web of Science, Embase, Ovid, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) using keywords such as botulism, Clostridium botulinum, botulinum antitoxin, botulism, botulinum, BoNT, antibacterial agents, antitoxins, botulinum antitoxin, respiration artificial, activated charcoal, cholinergic antagonists, drugs investigational, disaster planning, immunoglobulins, cholinergic, guanidine, anticholinergic, ventilation, antitoxin, antisera, antiserum, antibody, antibiotic, charcoal, pharmaceutical, germine, immunoglobulin, intubation, experimental animal, and nonhuman; the search strategy is detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1. Embase, Scopus, Medline, CINAHL contain conference proceedings and dissertations). Additionally we searched National Technical Information Service, Defense Technical Information Center, and Google Scholar for government documents, and manually included article references for additional studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included any article in the English language including case report, series, cohort, controlled trial, and animal study that reported patient-level data on the natural history of foodborne botulism or the effect of a directed treatment such as antitoxin. Botulism was defined by clinical diagnosis, epidemiologically (reported exposure known source with neurologic symptoms of botulism), or based on laboratory assays. Because of different pathophysiology, human cases of iatrogenic, infant, and wound botulism were excluded. Animal cases were excluded if they did not describe both controlled toxin exposure and antitoxin treatment. Case reports and series of <3 cases were abstracted for descriptive analysis, including specific rare treatments and outcomes, and excluded from meta-analysis and formal statistical analyses.

Article Screening and Abstraction

Articles were screened independently by 2 investigators (J. C. O. and P. K. T.) using Covidence (www.covidence.org), an online tool for systematic reviews. Initial screening entailed abstract review, followed by review of all potentially relevant full text articles. Reviewers determined if cases reported a case of foodborne botulism with discussion of both treatment strategies and clinical outcomes; if these criteria were met, the study was included. In both phases, disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus was reached on all articles.

Articles were abstracted using a standardized form developed on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Supplementary Appendix 2). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources [15]. Primary abstraction was completed by 1 of 8 reviewers (E. H., A. G. E. L., R. A., D. D., A. S., O. A., J. M., or E. T.) trained in use of the abstraction tool and definitions by 1 investigator (J. C. O.). All articles were independently abstracted and reviewed by a second reviewer (J. C. O. or P. K. T.). Disagreements were resolved through discussion at weekly meetings.

Data Abstraction

Articles were reviewed for outcomes including mortality, hospital length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and long-term neurologic sequelae. Articles were grouped first by the article type (case series, cohorts and trials, animal studies) and then by the intervention (eg, monovalent, bivalent, heptavalent antitoxin).

Meta-analysis

For meta-analytic purposes, we combined cohort studies, outbreak reports, or case series with N ≥3 to estimate the effect of antitoxin on mortality, ventilation, and hospital length of stay. In studies in which both the toxin type and antitoxin type were reported, only patients who received antitoxin which matched identified toxin exposures were considered “treated.”

For mortality analysis, the odds of death were calculated as a proportion of the total number of treated vs not-treated patients in a given report. Because in smaller studies the binomial distribution may not approximate the normal distribution, we performed a double arcsine Freeman-Tukey transformation to stabilize the variance and restore assumptions of normalcy. We calculated estimated variance by adding a proportionality constant to the observed number of deaths to adjust for zero values; this was equal to the reciprocal of the total number of subjects in the study. Resultant data were combined using the random-effects model prescribed by DerSimonian and Laird [16]. Subgroup analyses were performed by antitoxin type and toxin types. The odds of death for each type was calculated and compared. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2, where 0% indicates low heterogeneity and 100% high heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of a funnel plot using the method prescribed by Egger et al [17]. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) and Review Manager 5 (Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) software.

Duration of hospitalization and ventilation were modeled using mean and standard deviation data from cohorts and case series providing sufficient data to determine patients’ duration of treatment. On meta-analysis, only studies including both treated and untreated patients were analyzed, as interhospital ventilation and extubation practices were too great for indirect comparison.

Early vs late administration of antitoxin, defined by report authors, was analyzed relative to mortality, duration of ventilation, and duration of hospitalization using the methods described above. Subgroups were defined by (1) definitions given in the study for early vs late (Supplementary Appendix 8) or (2) patients who received antitoxin within 24 hours of presenting for medical care vs all others. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed on studies with sufficient patient-level data to exclude those who died when calculating length of stay and duration of hospitalization. This was performed to determine the effect of any survivor bias on these time-dependent variables. Finally, using study evidence ratings, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis excluding the 50% lowest-scoring studies as rated by the evidence-rating tool described below. Results from these sensitivity analyses were compared to the main outcomes to identify confounding by reporting and publication bias.

Meta-regression was performed on all studies by year of publication to determine the role that evolving supportive care techniques have played over time in each of these domains.

Individual Study Evidence Rating

Each publication was assessed by both reviewers for quality of evidence using a tool developed by the authors (Supplementary Appendix 3). This tool evaluates articles for design quality, level of certainty, and completeness of reporting. Study design and evidence were modified from the criteria used by the US Preventive Services Task Force. The risk-of-bias tool was modified from the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Completeness was assessed based on the presence of 15 pieces of information deemed pertinent to a botulism treatment article (Supplementary Appendix 3).

RESULTS

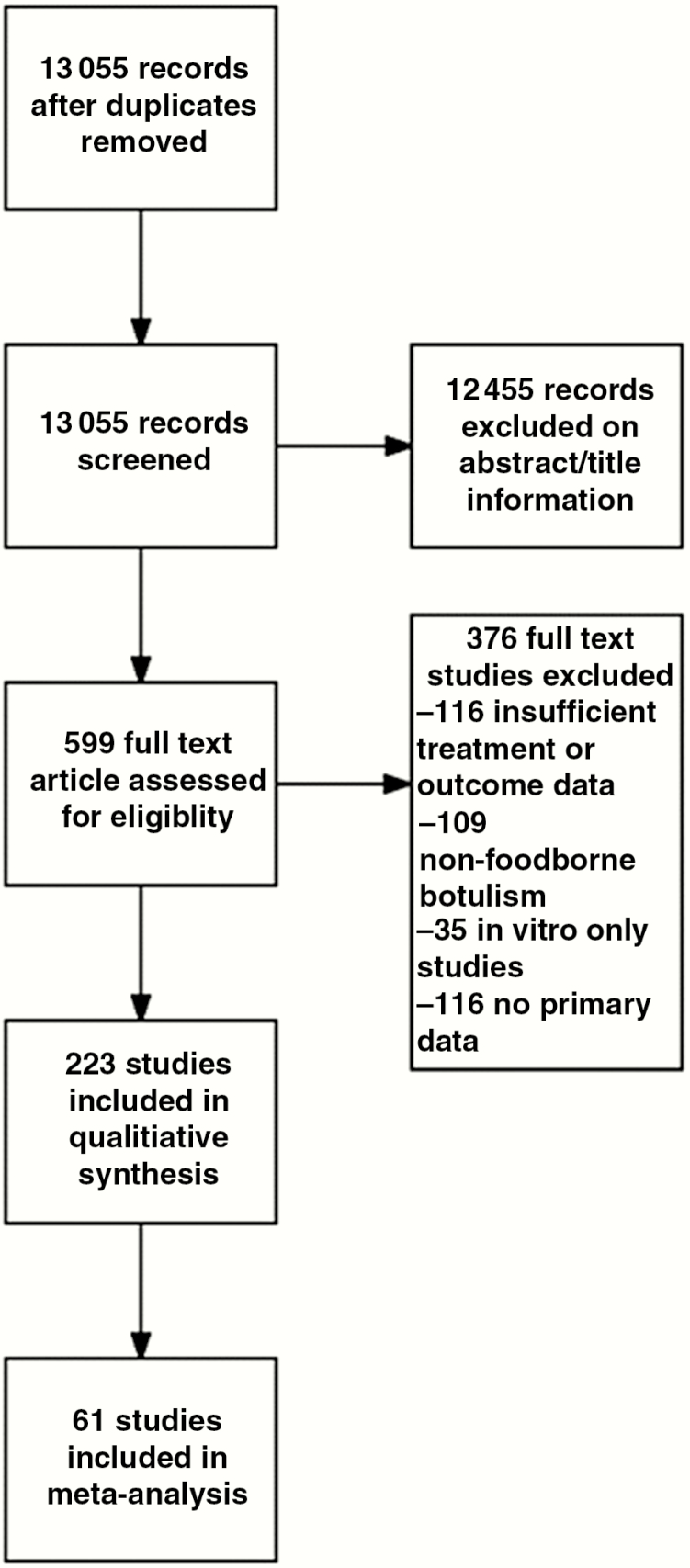

The search strategy yielded 13 055 distinct abstracts for screening. One abstract could not be obtained; 13069 were screened, of which 12455 studies were excluded. Full text evaluation was performed on 599 articles, of which 223 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Characteristics of the comparative studies included are described in Supplementary Appendix 7. Outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Additional details on the method of diagnosis are shown in Supplementary Appendix 8. Individual studies and case reports unsuitable for quantitative analysis are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) selection flow diagram for studies addressing botulism antitoxin therapy outcomes, 1948–2016.

Table 1.

Study Outcomes

| Study | Mortality | Ventilation | Hospitalization | Long term deficits | Adverse effects of antitoxin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolman et al, 1948[56] | 100% | 0% | 0% | N/A | N/A |

| Gray et al, 1948 [57] bNorthern Queensland |

27% | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gray et al, 1948[57] b Northern Territories | 20% | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Johnson and Style, 1949[39] | 25% | 0% | 100% | NR | NR |

| Dolman et al, 1954[58] | 60% mortality | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Dolman et al., 1963[18] | 19.1% overall 28.9% without antitoxin 3.5% with antitoxin |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Eadie et al., 1964[37] | 66% mortality; 50% with antitoxin | 1 patient ventilated for three days before death | Mean 2.3 days hospitalization | NR | 1 patient developed shock and vomiting after antitoxin, but recovered |

| Minter et al, 1964[42] | 0% | 66% required ventilation for a mean of 11 (1.4)days | Mean of 14.7 (3.1) days | None (duration of followup unspecified) | NR |

| Roger, 1964[49] | 60% mortality among those not receiving antitoxin 0% with dose who did |

2 out of 8 required mech ventilation | NR | NR | NR |

| Koenig et al., 1967[41] | 0% mortality | 1 ventilated for 4 days | Mean 9.8 (6.9) days | No residual effects at 6 weeks | NR |

| Armstrong et al, 1968[50] | 33%; the single case given antitoxin died | 1; the case receiving antitoxin was ventilated for 3 days before expiring | Two cases were hospitalized for four days | NR; notably one untreated case was pregnant and gave birth to a healthy child 2 months after recovery | NR |

| Fukuda et al, 1970[38] | 14.3%; two received type E antitoxin, one no antitoxin | NR | NR | NR | 1 receiving bivalent AB had a strong skin reaction |

| Faich et al, 1971[24] | 0% | 100%, ventilated from 3–12 weeks | Hospitalized for 3–15 weeks | NR | NR |

| Dolman et al., 1974[55] | 46% overall | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Cherington et al., 1975[59] | 14% mortality | 6 patients required ventilation (duration unspecified) | NR | Survivors were largely symptom free at 90 days; one patient had constipation | Fever following antitoxin administration (1 patient) Skin rash due to guanidine (1 patient) |

| Horwitz et al, 1975[27] | 66% mortality (1 treated with antitoxin, one untreated) | 2 required mechanical ventilation until death | NR | NR | Serum sickness due to trivalent antitoxin in survivor |

| Koenig et al., 1975[60] | 0% mortality | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Barrett et al., 1977[22] b Chefornak | 0% mortality | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Barrett et al., 1977[27] b New Stuyahok | 66% mortality | 1 patient required MV | NR | NR | NR |

| Puggiari and Cherington, 1978[61] | 0% mortality | 1 required six weeks of respiratory assistance | Hospitalized for 8 weeks weesk and 57 days | Recovery at 3 months | NR |

| Ball et al. 1979[62] | 50% mortality | NR | 47.5 (31.8) days | At 3 months, one had recovered completely and the other had residual weakness attributed to muscle wasting. | NR |

| Boselli et al, 1979[63] | 33%mortality | 1 required 87 days of ventilation, the other 16 months | NR | NR | NR |

| Nightingale et al., 1980[64] | 83% mortality | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Morris Jr. and Hatheway, 1980[65] | 0% mortality | 7/8 required ventilator for mean of 27 days | NR | NR | NR |

| Tacket et al, 1984[9] | 14.3% of patients died in the hospital 42% of these were directly attributable to botulism |

Median 25 days of support | Median 40 days of hospitalization | Not reported | None reported |

| Macdonald et al, 1985[66] | 1 died while still hospitalized six months after exposure | NR | NR | NR | 1/20 had serum sickness |

| Shih et al., 1986[67] | 12.5% of patients died overall 50% in pre-antitoxin era, 7.6% in post antitoxin era |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lecour et al., 1988[68] | 0% | NR | 27 days (range 8–37) | NR | NR |

| Critchley 1989 [69] | 4% mortality | 20.5 (14.5) days | 19.3 (17.7) days | 4% were not discharged within 60 days | None reported |

| Slater 1989[31] | 14% mortality | 3/7 required veintaltor support for a mean (SD) of 11.5 (2.1) days | NR | None reported in survivors | None reported |

| Barrett et al, 1991[21] | 6% attributed mortality | 14 patients were nasotracheally intubated for a mean 8.6 days (range 3–20). Nine tracheostomy 15.5 days (range 7–24). | NR | NR | None reported |

| Hibbs et al, 1996[70] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Angulo et al, 1998[20] | 0 deaths | NR | NR | NR | One hypersensitivity reaction, one case of pruritis |

| Chaudhry et al, 1998[2] | 3 deaths, all in untreated arm | 2 intubated duration unspecified | NR | NR | None reported |

Table 2.

Individual Case Report of Botulism Exposure, Treatment and Outcomes, 1946–2015

| Report | Patient characteristics | Method of confirmation | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miley 1946[71] | 27 year old female who consumed canned beets | Clinical appearance; no laboratory confirmation | Ultraviolet blood irradiation 24 hours after admission | Drastic improvement within 48 hours; complete resolution by hospital discharge on day 13 |

| Kendall 1949[72] | 33 year old female who consumed canned tongue | Clinical appearance; no laboratory confirmation | Supportive care | Eye and facial weakness persisted at 7 week evaluation |

| Bennet et al, 1964[73] | 51 year old female who consumed canned cantaloupe | Mouse bioassay confirmed type A botulism | Supportive care only; 21 days of ventilation | Death in hospital 26 days after admission |

| Cherington and Ryan, 1968[74] | 57 year old female who consumed canned string beans | Clinical appearance | Supportive care, 27 days of ventilation, guanidine | Death 34 days after admission EMG and strength improved following each administration of guanidine transiently |

| Haller et al., [75] | 53 year old male consuming canned tomato juice | Clinical appearance and serum/stool testing (assay unspecified) | Bivalent AB antitoxin, IV procaine penicillin | Discharge 9 days after admission; 10 weeks after exposure, no residual symptoms |

| Cherington and Ryan, 1970[76] | 43 year old female exposed to type A botulism by canned potato salad | Mouse bioassay | Bivalent AB antitoxin, guanidine, 28 days of ventilation | Hospitalized for 42 days, continued to have proximal muscle weakness 6 weeks after discharge |

| Craig et al, 1970[77] | 31 year old male with type E botulism from izushi exposure | Mouse bioassay | Monovalent E antitoxin | Death 109 hours following contaminated meal |

| Oh and Halsey, 1975[78] | 54 year old male exposed to type B botulism from preserved tomatoes | Mouse bioassay | AB antitoxin on day 4 after hospitalization; guanidine for two prolonged courses; intubated x 26 days | Strength improved on guanidine infusion. |

| Rosenthal and Belafsky, 1975[79] | 34 year old male exposed to type B botulism from canned vegetables (beets) | Testing of food jar; assay unspecified | Trivalent ABE antitoxin | Patient discharged 12 days after admission had sluggish pupils on discharge |

| Blake et al., 1977[80] | Two women exposed to type A botulism from canned beef | Mouse bioassay and culture | Surviving patient received trivalent ABE antitoxin; guanidine; penicillin V; edrophonium | One died within 2 hours of hospitalization; the other had a prolonged course but survived to discharge 64 days later with mild generalized weakness |

| Cherington and Schultz, 1977[59] | 40 year old female exposed to canned vegetables | Clinical diagnosis Stool + for toxin (assay unspecified) |

Guanidine Germine-3-acetate Bivalent antitoxin Required intubation |

Improved symptomatically after administration of guanidine Recovered completely |

| Maroon and Bisonnette., 1977[81] | 57 year old male with foodborne type B exposure | Mouse bioassay | Trivalent ABE | Residual weakness was noted at 1.5 year follow up |

| Puggiari and Cherington, 1978[61] | 41 year old female and 18 year old female exposed to canned peppers | Clinical diagnosis | Guanidine | Ocular improvement and non-respiratory muscle improvement after guanidine |

| Riddle, 1985[82] | 23 year old female exposed to type A botulism from canned tomatoes | Stool/serum and food positive for toxin (assay unspecified) | Trivalent ABE Ventilation |

Improvement in respiratory strength after antitoxin administration Discharged 23 days later with residual weakness |

| Colebatch et al. 1989[83] | 49 year old male with type A botulism after eating rice & vegetables | Mouse bioassay | Unspecified polyvalent antitoxin Required intubation |

Residual deficits persisted two years later |

| Martinez-Castrillo et al, 1991[84] | 43 year old female with type B botulism after eating canned beans | Clinical appearance Food/serum positive for toxin B (assay unknown) |

Trivalent ABE | Still had dry eyes/mouth 30 days later Full recovery within 60 days |

| Davis et al., 1992[85] | 31 year old male with type A botulism after eating canned green chilli | Stool/food jar tested positive (assay not reported) | 3,4 DAP Trivalent ABE Ventilation |

Survival and improvement at 90 days; no improvement was noted around time of 3,4 DAP administration |

| Paterson et al., 1992[86] | 33 year old male after eating home preserved asparagus | Clinical appearance | Trivalent ABE, vancomycin and plasmapheresis Required intubation |

All symptoms resolved within 6 weeks |

| Mackle et al, 2001[87] | 62 year old male with type E botulism after eating reheated cold chicken | Mouse bioassay | Supportive care | Recovery over several months |

| Cengiz et al, 2004[88] | 40 year old female with canned green bean exposure | Clinical appearance | Bivalent AB and monovalent E antitoxin | Complete recovery within 3 months |

| Bhutani et al., 2005[89] | 35 year old male with type A botulism from potatoes | Cultures, Toxin assays (assay not reported) | Trivalent antitoxin Intubation |

Complete resolution after 6 ½ months |

| Al Nassar et al., 2012[90] | 28 year old female with botulism from Faseikh | Stool culture | Trivalent ABE antitoxin Intubation |

Complete resolution |

| Vasa et al., 2012[91] | 69 year old male with type A botulism after eating green beans/ tomatoes | Unknown assay | Monovalent A antitoxin | Recovery 5 months after exposure |

| Centers for disease control, 2013[92] | 39 year old male exposed to type B botulism from home fermented tofu | Mouse bioassay | Antitoxin, unspecified Intubated IVIG and edrophonium were also administered for suspected myasthenia gravis |

Discharge from hospital 23 days later |

| Gasparini et al., 2013[93] | 78 year old female with submandibular sialadenitis, exposure unknown | PCR on stool and rectal swab | Trivalent antitoxin ABE Antibiotics |

Complete resolution |

| Kotan et al, 2013[94] | 43 year old female after eating homemade canned beans | Clinical Appearance | Bivalent antitoxin A | Resolution by 6 weeks |

| Pender et al, 2013[95] | 91 year old female with type A foodborne botulism after eating home canned borscht | Mouse bioassay | Unspecified antitoxin and edrophonium Required intubation |

Residual dysphagia persisted beyond hospital discharge |

| Zhang et al., 2013[96] | 33 year old male with type E botulism after eating dried crude beef | Food specimen culture, assay unknown | Gastric lavage, antibiotics, supportive care Required intubation |

No residual symptoms at time of hospital discharge |

| Arora et al, 2014[97] | 35 year old male after eating stale Dahi vada | Clinical diagnosis | Antibiotics, cathartics, hydrocortisone | Survival to discharge |

| Anniablli et al., 2015[98] | 21 year old male with type B botulism from canned turnips | Mouse bioassay | Unspecified antitoxin, metoclopramide Required intubation |

Resolution of symptoms by discharge |

Patient Characteristics

Data tying individual outcomes to age, gender/sex, comorbidities, and severity of illness at time of initial contact with medical care were reported inconsistently. While we cannot exclude that some populations may receive greater benefit from antitoxin treatment, we could not identify such a subpopulation on the basis of the highly limited data set.

Supportive Care

All articles that described survival alluded to the importance of high-quality supportive care, particularly respiratory critical care. However, insufficient detail (eg, modes of mechanical ventilation and nutritional support) in these publications precluded evaluation of specific intensive care components on clinical outcomes.

Relationship Between Type of Toxin and Clinical Outcome

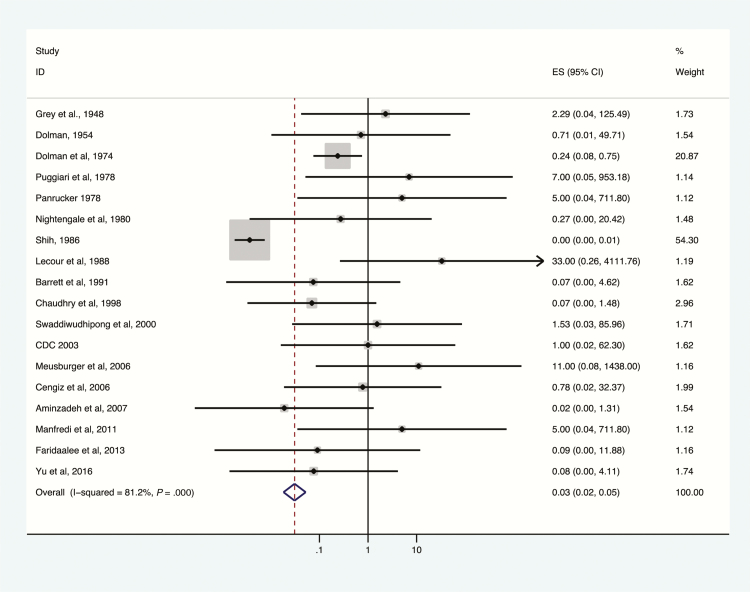

Mortality among patients treated and not treated with antitoxin, by toxin type, is presented in Figures 2–5. Overall, antitoxin reduced mortality (odds ratio [OR], 0.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], .17–.29); a high degree of heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 69.3%). Heterogeneity was largely due to studies not reporting toxin type (Figure 2). Subset analyses by toxin type were significantly less heterogeneous as described below. On meta-regression modeling, study year, design, selection, comparability, and completeness variables were not substantial contributors to heterogeneity (P = 0.86). Egger test identified no evidence of publication bias (P = 0.26).

Figure 2.

Deaths among botulism patients, antitoxin treatment vs no antitoxin treatment, unspecified toxin type, 1948–2016. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) demonstrated by point and lines extending to either side. Effect size (ES) and weighting illustrated by gray squares. Overall effect estimates provided by diamonds, centered on the odds ratio with points extending to the 95% CI.

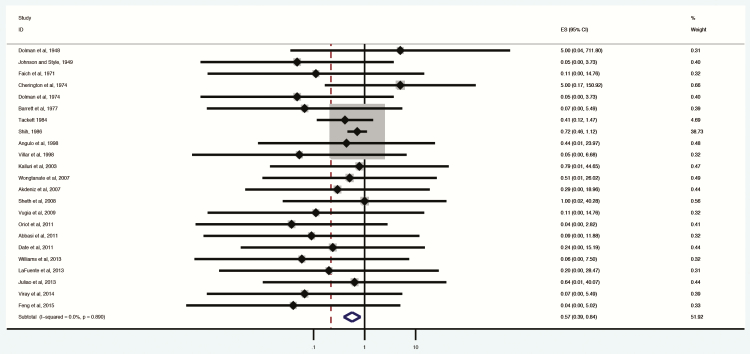

Figure 3.

Deaths among botulism patients, antitoxin treatment vs no antitoxin treatment, toxin type A, 1948–2016. Subset of figures reporting administration of antitoxin containing antitoxin A to confirmed toxin type A exposures. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) demonstrated by point and lines extending to either side. Effect size (ES) and weighting illustrated by gray squares. Overall effect estimates provided by diamonds, centered on the odds ratio with points extending to the 95% CI.

Figure 4.

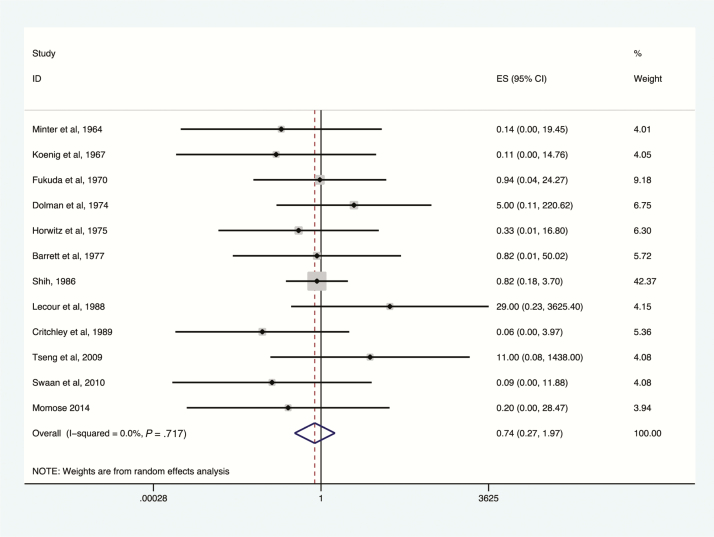

Deaths among botulism patients, antitoxin treatment vs no antitoxin treatment, toxin type B. Subset of figures reporting administration of antitoxin containing antitoxin B to confirmed toxin type B exposures. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) demonstrated by point and lines extending to either side. Effect size (ES) and weighting illustrated by gray squares. Overall effect estimates provided by diamonds, centered on the odds ratio with points extending to the 95% CI.

Figure 5.

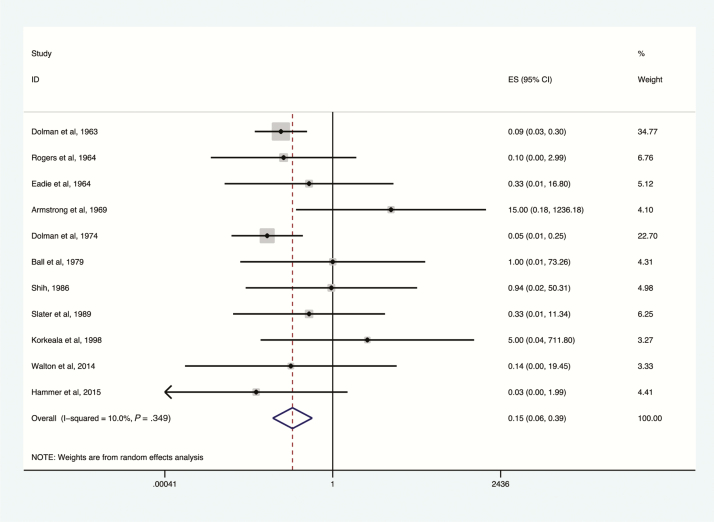

Deaths among botulism patients, antitoxin treatment vs no antitoxin treatment, toxin type E, 1963–2015. Subset of figures reporting administration of antitoxin containing antitoxin E to confirmed toxin type E exposures. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) demonstrated by point and lines extending to either side. Effect size (ES) and weighting illustrated by gray squares. Overall effect estimates provided by diamonds, centered on the odds ratio with points extending to the 95% CI.

The greatest reduction in botulism-related mortality was associated with the use of type E antitoxin (OR, 0.13; 95% CI, .06–.30; I2 = 10%; Figure 5), followed by type A antitoxin (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, .39–.84; I2 = 81.2%; Figure 3); reduction in mortality was not statistically significant for type B antitoxin (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, .27–1.97; Figure 4). Key data on the impact of type E antitoxin come from Dolman and Iida, who examined Canadian mortality rates of botulism type E before (baseline) and after introduction of type E antitoxin therapy [18]. Baseline mortality in this study was derived from secondary data and was thus excluded from the meta-analysis. Dolman and Iida’s baseline was derived from 75 outbreaks with 374 patients in 6 countries; case fatality rate was 30%. In Canada, in 28 outbreaks, 85 of 220 patients were treated with anti-E antitoxin. Among patients not treated with antitoxin, 28.9% died, compared with 3.5% of those treated [18].

Use of Different Antitoxin Formulations

Studies that reported both toxin type and administered antitoxin type were less heterogeneous overall and demonstrated a survival benefit to antitoxin (OR, 0.16; .09–.30; I2 = 0%; Figure 6). Fifteen studies reported use of trivalent antitoxin, 10 bivalent antitoxin, and 2 heptavalent antitoxin.

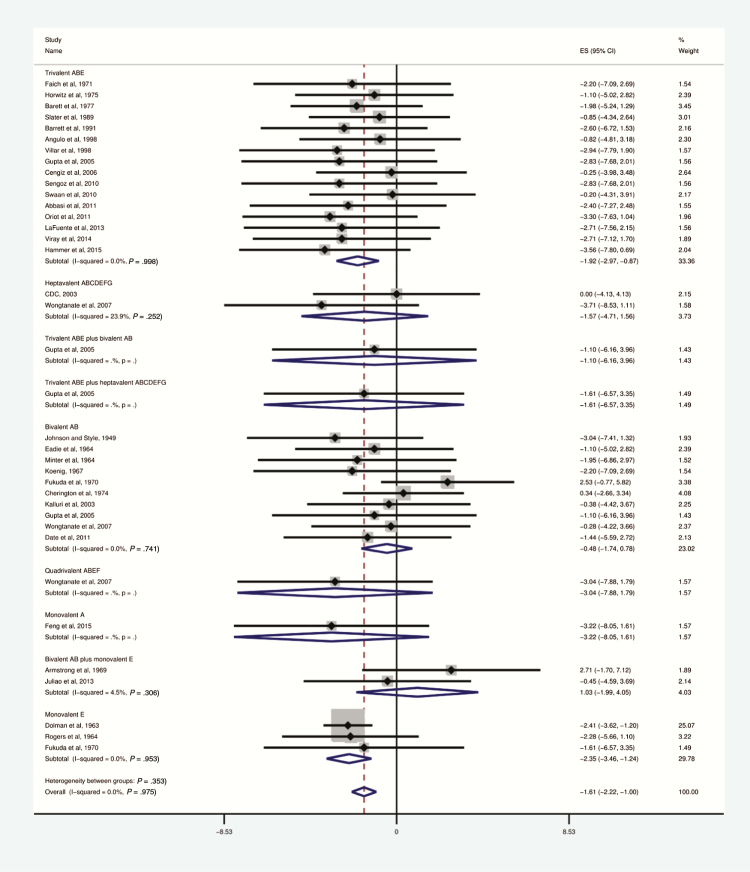

Figure 6.

Survival of botulism-exposed patients by antitoxin valence, 1948–2015.

Only studies reporting specific antitoxin type included. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) demonstrated by point and lines extending to either side. Effect size (ES) and weighting illustrated by gray squares. Subgroup and overall effect estimates provided by diamonds, centered on the odds ratio with points extending to the 95% CI.

Use of anti-ABE trivalent antitoxin was most commonly reported [19–34]. Trivalent antitoxin, when administered in cases of botulism types A, B, or E, reduced mortality (OR, 0.13; 95% CI, .04–.38; I2 = 0%). Side effects from this formulation were less commonly reported than all other antitoxins with side effects reported. Anti-ABE antitoxin was generally reported as effective and well tolerated. Case series reported occasional residual neuromuscular deficits persisting up to several months after therapy (Table 2).

Bivalent AB antitoxin was the second most commonly reported formulation [25, 35–43]; its use was not significantly associated with reduction in mortality (OR, 0.37; 95% CI, .10–1.31; I2 = 0%). Information on heptavalent antitoxin includes 2 reports of foodborne botulism outbreaks. One was caused by toxin type A–contaminated canned bamboo in Thailand [43–45] and affected 137 patients, of whom 20 were treated with heptavalent antitoxin, and the others with bivalent AB or quadrivalent ABEF antitoxin. No deaths were reported. The second outbreak, caused by type A toxin, affected 8 prison inmates in Utah [46]. All received heptavalent antitoxin; none died. Low mortality in both outbreaks was attributed to excellent critical and supportive care of the patients [45].

The largest available data source on heptavalent antitoxin was the unpublished Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s expanded-access Investigational New Drug application. Data included mostly foodborne botulism cases and several cases of wound botulism, infant botulism, and other syndromes. Of 249 patients treated under this protocol, 105 were confirmed as having botulism. One child experienced hemodynamic instability after administration, comprising the only serious adverse event seen with heptavalent antitoxin. Allergic reactions, typically rash, were noted in 6 patients, all of whom recovered without sequelae. Seven deaths were observed in confirmed botulism cases treated with heptavalent antitoxin; none were attributed to the antitoxin [47].

A variety of other antitoxin combinations are reported in Figure 6, including quadrivalent ABEF [43], monovalent A [48], monovalent E [18, 49], and a combination of bivalent AB formulation and monovalent E formulation [50, 51]. The small number of deaths from botulism reported in patients treated with these agents precludes a statistical assessment of their impact on clinical outcomes.

Effect of Timing of Antitoxin Administration

Kongsaengdao et al [44] reported on a subset of 18 severely ill patients during a type A outbreak associated with bamboo shoots in Thailand examined in Wongtanate et al [43] and Wintoonpanich et al [45]. In this subset, patients who received antitoxin on day 4 had significantly shorter duration of ventilator dependence compared with those receiving it on day 6 [44].

Sheth et al reported on 6 patients in a botulism type B outbreak associated with bottled carrot juice. Five patients received antitoxin: 3 within 24 hours, 1 on day 13, and 1 on day 45. At the time of publication, 2 patients had been ventilator dependent for >1 year [52]. We treated these patients as having 365 ventilator-days, demonstrating some reduction in ventilator time in those who had early treatment.

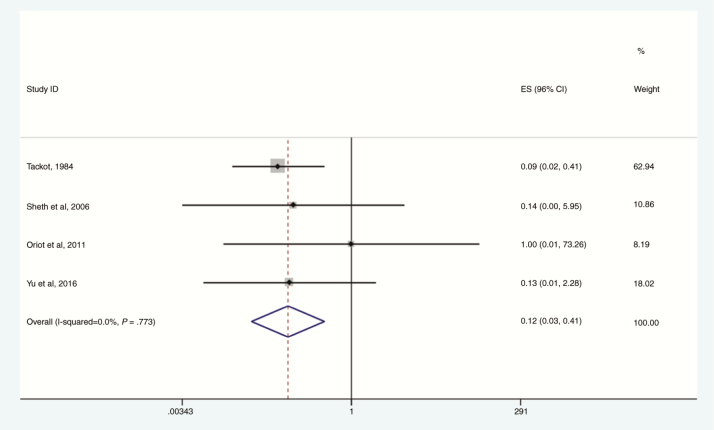

Yu et al also reported a benefit from heptavalent antitoxin given within 48 hours compared with later administration [47]. In patients treated early, the proportion of patients requiring mechanical ventilation was significantly reduced and there were no deaths, compared with 7 deaths among patients treated later. Overall, earlier antitoxin administration reduced mortality, compared with later administration (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, .03–.41; I2 = 0%; Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Survival for botulinum neurotoxin–exposed patients with early vs late exposure to antitoxin, 1984–2016. Four studies which reported “early” vs “late” groups included. Definitions varied between studies; Sheth et al and Tacket et al defined “early” as within administration within 24 hours of presentation and late as all others. Yu et al and Oriot et al reported outcomes for before and after 48 hours postpresentation to care. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

Animal Studies

In general, animal studies showed some benefit to antitoxin treatment (Supplementary Appendices 5 and 9).

Therapeutic Agents Other Than Antitoxin

We identified no improvement with several agents reported in the literature (Supplementary Appendix 6).

Study Quality Assessments

Most studies were rated as level III evidence (case reports and series, opinions of expert authorities) (Supplementary Appendix 4). Outcome assessments were not consistently high quality, with a mean of 5/12 on our scoring rubric. Completeness of reporting was generally good, with an average score of 11/16.

Study design was not a major contributor to interobserver variability (P = .50). Study outcome assessments were similarly not a major contributor (P = .54). Completeness was also not significantly associated on meta-regression (P = .31).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic, comprehensive literature review of botulism treatment, we examined all relevant publications since the early 20th century. Our findings support the routine administration of botulinum antitoxin to botulism patients. Antitoxin treatment reduces mortality, and the available data show that earlier antitoxin administration reduces both mortality and ventilation time, compared with later administration. However, there are reports of benefit even with late antitoxin administration, defined by the authors as anywhere from >24 hours after illness onset to 48 hours after presentation. We found no clear indication of a point in the course of illness at which antitoxin administration was no longer beneficial. Although the nature of the data did not allow for quantitative analysis of the benefits of supportive care, this modality is doubtless essential to survival of patients with severe botulism, as evidenced by decreased mortality since the introduction of ventilator care in the 1960s. Despite some early promising studies for guanidine, we did not identify clear or sustained benefit to any alternative treatment modalities applied to botulism patients.

Qualitative studies and case reports broadly supported treatment with botulinum antitoxin. Several older studies dating to the first half of the 20th century reported dramatic clinical resolution following antitoxin administration with all types (Table 2); the significance of these observations is unclear. It is worth noting that while mortality in patients not treated with antitoxin was high, often these patients did not have access to advanced life support. Therefore, these poor outcomes were likely influenced by the lack of supportive care.

Available data do not suggest any patient characteristics that predict a response to therapy. Because the data do not provide evidence of demographic or clinical indicators for predictors of better outcome, we cannot recommend any specific criteria for prioritizing antitoxin treatment when its availability is limited. Further study is needed to risk-stratify patients and identify patients likeliest to benefit from antitoxin treatment.

Correspondence between toxin types and antitoxin serotype corresponded with clinical outcome. The currently licensed heptavalent antitoxin provides appropriate treatment for botulism caused by serotypes A–G. Data available to us were limited to unpublished prelicensure surveillance. Therefore, treatment outcomes should be monitored and analyzed on an ongoing basis.

Recently, reports of new toxin types have been published, including a novel toxin subsequently shown to be a hybrid type A/F fully neutralized by HBAT [53, 54] and a novel toxin identified and assembled from the published gene sequence of a C. botulinum isolate [55]. These reports illustrate important challenges in the field of botulism. New botulinum toxins of clinical significance may be discovered. The routine analysis and dissemination of clostridial gene sequences can accelerate such discoveries, and likely facilitate assembly of toxins, for purposes hopefully benign but possibly nefarious. Preparedness requires careful laboratory investigation of all suspected botulism cases and ongoing research and development of new countermeasures.

Appropriate supportive care is considered a cornerstone in survival and recovery from botulism [56, 57]. It must be borne in mind that a substantial proportion of botulism patients suffer respiratory compromise, some despite prompt diagnosis and early antitoxin treatment; therefore, survival of some botulism patients, treated or untreated with antitoxin, depends on high-quality intensive care. Longstanding experience shows that deaths from botulism can be averted by providing meticulous intensive care, including ventilator care when required [52]. Antitoxin should be given as soon as possible along with meticulous intensive care. Likewise, mortality in case series and reports was highest in patients remote from hospital or emergency care facilities. Early recognition and best intensive care unit practices are an important part of the comprehensive care of the botulism patient. In a situation of limited antitoxin availability, the availability of critical supportive care will determine survival for patients experiencing respiratory compromise. Critical care is an essential component of emergency preparedness for botulism events, both naturally occurring and intentionally created.

Our study has several limitations. We did not include reports of wound botulism in the review, so our findings may not fully apply to that syndrome. Although we made every effort to separate outbreaks and case reports to avoid analyzing the same individual twice, the way that outbreaks are reported and analyzed, particularly in older literature, makes this nearly impossible. For example, several patients are likely reported in each of 2 case series reported by Dolman [18, 58] likely, but it is impossible to determine which. We attempted to account for this with several sensitivity analyses serially excluding these and other high overlap studies; we did not see a substantial change in our overall results.

Our review includes publications spanning 8 decades. Aside from improvements in antitoxin manufacture, types, and valence, this period encompasses dramatic improvements in supportive care technology and techniques and the rise of critical care as a specialty. The effect of these on outcomes is profound, but we could not methodologically account for it in our results. We must therefore accept that some of the benefit attributed to antitoxin may in fact be due to some of these advances. Thus, we cautiously interpret our results to suggest that appropriate antitoxin therapy in conjunction with high-quality supportive care produce the best outcomes in botulism patients.

A final limitation is our inability to adjust for the effect of disease progression and timing. Although we did observe some benefit from early antitoxin administration as defined by the report authors, several confounders are inherent in this finding. First, early administration may have been a marker for early recognition and initiation of other interventions. Second, early administration in several studies may have reflected early treatment of clinically milder cases that presented after delayed diagnosis of a severely ill outbreak index case. However, a beneficial effect of early antitoxin administration was reported in nearly all studies examining this measure. Overall, this would support a benefit of earlier administration, but we may have overestimated the degree of benefit.

Another significant limitation is our focus on foodborne botulism. This was done primarily because of the different physiology involved in foodborne, infant, and iatrogenic botulism, and allowed us to focus on a less heterogenous population experiencing the most common form of botulism. We do not know how these findings may apply to other forms of botulism.

In conclusion, we found that early administration of antitoxin of serotype-appropriate antitoxin, along with high-quality supportive care, was consistently associated with reduced mortality in botulism patients. No demographic or clinical predictors of the response to antitoxin were identified.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Joanne Taliano, CDC librarian, for her role in developing and executing the systematic review literature search; and Elliott Churchill, for expert editorial advice.

Disclaimer. The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The inclusion of commercial product or entity names is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by NIH or CDC.

Financial support. This work was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant number UL1 TR000135). J. C. O.’s time was supported by the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery at Mayo Clinic.

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “Botulism,” sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Montecucco C, Molgó J. Botulinal neurotoxins: revival of an old killer. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005; 5:274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaudhry R, Dhawan B, Kumar D et al. Outbreak of suspected Clostridium butyricum botulism in India. Emerg Infect Dis 1998; 4:506–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV et al. ; Working Group on Civilian Biodefense Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 2001; 285:1059–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biological and chemical terrorism: strategic plan for preparedness and response. Recommendations of the CDC Strategic Planning Workgroup. MMWR Recomm Rep 2000; 49(RR-4):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dembek ZF, Smith LA, Rusnak JM. Botulism: cause, effects, diagnosis, clinical and laboratory identification, and treatment modalities. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2007; 1:122–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalia J, Swartz KJ. Elucidating the molecular basis of action of a classic drug: guanidine compounds as inhibitors of voltage-gated potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol 2011; 80:1085–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher RW.Approval letter—BAT. 2013. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/ApprovedProducts/LicensedProductsBLAs/FractionatedPlasmaProducts/UCM358262.pdf. Accessed March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sobel J, Tucker N, Sulka A, McLaughlin J, Maslanka S. Foodborne botulism in the United States, 1990–2000. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:1606–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tacket CO, Shandera WX, Mann JM, Hargrett NT, Blake PA. Equine antitoxin use and other factors that predict outcome in type A foodborne botulism. Am J Med 1984; 76:794–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arnon SS, Schechter R, Maslanka SE, Jewell NP, Hatheway CL. Human botulism immune globulin for the treatment of infant botulism. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:462–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson JA, Filloux FM, Van Orman CB et al. Infant botulism in the age of botulism immune globulin. Neurology 2005; 64:2029–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tseng-Ong L, Mitchell WG. Infant botulism: 20 years’ experience at a single institution. J Child Neurol 2007; 22:1333–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Underwood K, Rubin S, Deakers T, Newth C. Infant botulism: a 30-year experience spanning the introduction of botulism immune globulin intravenous in the intensive care unit at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. Pediatrics 2007; 120:e1380–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–9, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dolman CE, Iida H. Type E botulism: its epidemiology, prevention and specific treatment. Can J Public Health 1963; 54:293–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abbasi F, Vahdani P, Behzad HR, Beshart M. Botulism outbreak in northern Iran: five cases in one family. Int J Infect Dis 2011; 15:S51. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Angulo FJ, Getz J, Taylor JP et al. A large outbreak of botulism: the hazardous baked potato. J Infect Dis 1998; 178:172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barrett DH. Endemic food-borne botulism: clinical experience, 1973–1986 at Alaska Native Medical Center. Alaska Med 1991; 33:101–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barrett DH, Eisenberg MS, Bender TR, Burks JM, Hatheway CL, Dowell VR Jr. Type A and type B botulism in the North: first reported cases due to toxin other than type E in Alaskan Inuit. Can Med Assoc J 1977; 117:483–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cengiz M, Yilmaz M, Dosemeci L, Ramazanoglu A. A botulism outbreak from roasted canned mushrooms. Hum Exp Toxicol 2006; 25:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faich GA, Graebner RW, Sato S. Failure of guanidine therapy in botulism A. N Engl J Med 1971; 285:773–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gupta A, Sumner CJ, Castor M, Maslanka S, Sobel J. Adult botulism type F in the United States, 1981–2002. Neurology 2005; 65:1694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hammer TH, Jespersen S, Kanstrup J, Ballegaard VC, Kjerulf A, Gelvan A. Fatal outbreak of botulism in Greenland. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015; 47:190–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Horwitz MA, Marr JS, Merson MH, Dowell VR, Ellis JM. A continuing common-source outbreak of botulism in a family. Lancet 1975; 2:861–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lafuente S, Nolla J, Valdezate S et al. Two simultaneous botulism outbreaks in Barcelona: Clostridium baratii and Clostridium botulinum. Epidemiol Infect 2013; 141:1993–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oriot C, D’Aranda E, Castanier M et al. One collective case of type A foodborne botulism in Corsica. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:752–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sengoz G, Bakar M, Kina Senoglu E et al. Botulismus epidemic caused by home-made canned food and 8 members affected in a family. In: European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slater PE, Addiss DG, Cohen A et al. Foodborne botulism: an international outbreak. Int J Epidemiol 1989; 18:693–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Swaan CM, van Ouwerkerk IM, Roest HJ. Cluster of botulism among Dutch tourists in Turkey, June 2008. Euro Surveill 2010; 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Villar RG, Shapiro RL, Busto S et al. Outbreak of type A botulism and development of a botulism surveillance and antitoxin release system in Argentina. JAMA 1999; 281:1334–8, 1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Viray MA, Wamala J, Fagan R et al. Outbreak of type A foodborne botulism at a boarding school, Uganda, 2008. Epidemiol Infect 2014; 142: 2297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cherington M. Botulism. Ten-year experience. Arch Neurol 1974; 30:432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Date K, Fagan R, Crossland S et al. Three outbreaks of foodborne botulism caused by unsafe home canning of vegetables—Ohio and Washington, 2008 and 2009. J Food Prot 2011; 74: 2090–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eadie GA, Molner JG, Solomon RJ, Aach RD. Type E botulism. Report of an outbreak in Michigan. JAMA 1964; 187:496–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fukuda T, Kitao T, Tanikawa H, Sakaguchi G. An outbreak of type B botulism occurring in Miyazaki Prefecture. Jpn J Med Sci Biol 1970; 23:243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson DE, Styles GW. Botulism in human beings from home and commercially canned foods. Rocky Mt Med J 1949; 46:740–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kalluri P, Crowe C, Reller M et al. An outbreak of foodborne botulism associated with food sold at a salvage store in Texas. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:1490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koenig MG, Drutz DJ, Mushlin AI, Schaffner W, Rogers DE. Type B botulism in man. Am J Med 1967; 42:208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Minter DL, Roscoe RE, Gordon WS. Three cases of botulism. Pa Med J 1964; 67:39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wongtanate M, Sucharitchan N, Tantisiriwit K et al. Signs and symptoms predictive of respiratory failure in patients with foodborne botulism in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 77:386–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kongsaengdao S, Samintarapanya K, Rusmeechan S et al. ; Thai Botulism Study Group An outbreak of botulism in Thailand: clinical manifestations and management of severe respiratory failure. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Witoonpanich R, Vichayanrat E, Tantisiriwit K et al. Survival analysis for respiratory failure in patients with food-borne botulism. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010; 48:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Botulism from drinking prison-made illicit alcohol—Utah 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:782–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu P. Heptavalent botulinum antitoxin (BAT) use in patients treated under CDC’s expanded access IND, 2010–2013. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feng L, Chen X, Liu S, Zhou Z, Yang R. Two-family outbreak of botulism associated with the consumption of smoked ribs in Sichuan Province, China. Int J Infect Dis 2015; 30:74–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rogers DE, Koenig MG, Spickard A. Clinical and laboratory manifestations of type E botulism in man. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1964; 77:135–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Armstrong RW, Stenn F, Dowell VR Jr, Ammerman G, Sommers HM. Type E botulism from home-canned gefilte fish. Report of three cases. JAMA 1969; 210:303–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Juliao PC, Maslanka S, Dykes J et al. National outbreak of type A foodborne botulism associated with a widely distributed commercially canned hot dog chili sauce. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:376–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sheth AN, Wiersma P, Atrubin D et al. International outbreak of severe botulism with prolonged toxemia caused by commercial carrot juice. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barash JR, Arnon SS. A novel strain of Clostridium botulinum that produces type B and type H botulinum toxins. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maslanka SE, Lúquez C, Dykes JK et al. A novel botulinum neurotoxin, previously reported as serotype H, has a hybrid-like structure with regions of similarity to the structures of serotypes A and F and is neutralized with serotype A antitoxin. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:379–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang S, Masuyer G, Zhang J et al. Identification and characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sobel J. Botulism. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shapiro RL, Hatheway C, Swerdlow DL. Botulism in the United States: a clinical and epidemiologic review. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dolman CE. Human botulism in Canada (1919–1973). Can Med Assoc J 1974; 110:191–7 passim. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cherington M, Schultz D. Effect of guanidine, germine, and steroids in a case of botulism. Clin Toxicol 1977; 11:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Koenig H, Gassman HB, Jenzer G. Ocular involvement in benign botulism B. Am J Ophthalmol 1975; 80:I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Puggiari M, Cherington M. Botulism and guanidine. Ten years later. JAMA 1978; 240: 2276–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ball AP, Hopkinson RB, Farrell ID et al. Human botulism caused by Clostridium botulinum type E: the Birmingham outbreak. Q J Med 1979; 48:473–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Boselli L, Jato E, Selenati A, Sottili S, Bozza Marrubini M. Three cases of severe botulism. Vet Hum Toxicol 1979; 21(Suppl):111–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nightingale KW, Ayim EN. Outbreak of botulism in Kenya after ingestion of white ants. Br Med J 1980; 281:1682–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Morris JG Jr, Hatheway CL. Botulism in the United States, 1979. J Infect Dis 1980; 142:302–5. [Google Scholar]

- 66. MacDonald KL, Spengler RF, Hatheway CL, Hargrett NT, Cohen ML. Type A botulism from sauteed onions. Clinical and epidemiologic observations. JAMA 1985; 253:1275–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shih Y, Chao SY. Botulism in China. Rev Infect Dis 1986; 8:984–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lecour H, Ramos H, Almeida B, Barbosa R. Food-borne botulism. A review of 13 outbreaks. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:578–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Critchley EM, Hayes PJ, Isaacs PE. Outbreak of botulism in north west England and Wales, June, 1989. Lancet 1989; 2:849–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hibbs RG, Weber JT, Corwin A et al. Experience with the use of an investigational F(ab’)2 heptavalent botulism immune globulin of equine origin during an outbreak of type E botulism in Egypt. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 23:337–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Miley GP. Recovery from botulism coma following ultraviolet blood irradiation. Rev Gastroenterol 1946; 13:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kendall D. Recovery from botulism. Br Med J 1949; 2:1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bennet NM, Stevenson WJ. A case of human botulism due to home-preserved cantaloupe. Med J Aust 1964; 1:758–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cherington M, Ryan DW. Botulism and guanidine. N Engl J Med 1968; 278:931–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Haller HD, May RT, Roth RL. Botulism—a case report. J Ky Med Assoc 1969; 67:820–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cherington M, Ryan DW. Treatment of botulism with guanidine. Early neurophysiologic studies. N Engl J Med 1970; 282:195–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Craig JM, Iida H, Inoue K. A recent case of botulism in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Med Sci Biol 1970; 23:193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Oh SJ, Halsey JH Jr, Briggs DD Jr. Guanidine in type B botulism. Arch Intern Med 1975; 135:726–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rosenthal NP, Belafsky M. Botulism: a case report. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc 1975; 40:165–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Blake PA, Horwitz MA, Hopkins L et al. Type A botulism from commercially canned beef stew. South Med J 1977; 70:5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Maroon JC. Late effects of botulinum intoxication. JAMA 1977; 238:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Riddle JD. Botulism—a case report. J Okla State Med Assoc 1985; 78:441–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Colebatch JG, Wolff AH, Gilbert RJ et al. Slow recovery from severe foodborne botulism. Lancet 1989; 2:1216–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Martinez-Castrillo JC, Del Real MA, Hernandez Gonzalez A, De Blas G, Alvarez-Cermeno JC. Botulism with sensory symptoms: a second case. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991; 54:844–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Davis LE, Johnson JK, Bicknell JM, Levy H, McEvoy KM. Human type A botulism and treatment with 3,4-diaminopyridine. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1992; 32:379–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Paterson DL, King MA, Boyle RS et al. Severe botulism after eating home-preserved asparagus. Medical J Aust 1992; 157:269–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mackle IJ, Halcomb E, Parr MJ. Severe adult botulism. Anaesth Intensive Care 2001; 29:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cengiz N, Turker H, Kiziltan M. Clinical and electrodiagnostic follow up of a case of food borne botulism. Marmara Med J 2004; 17:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Bhutani M, Ralph E, Sharpe MD. Acute paralysis following “a bad potato”: a case of botulism. Can J Anaesth 2005; 52:433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Al Nassar M, Mokhtar M, Rotimi VO. A case of adult botulism following ingestion of contaminated Egyptian salted fis (“Faseikh”). Kuwait Med J 2012; 44:63–5. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Vasa M, Baudendistel TE, Ohikhuare CE et al. Clinical problem-solving. The eyes have it. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:938–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Botulism associated with home-fermented tofu in two Chinese immigrants—New York City, March–April 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:529–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gasparini S, Ferlazzo E, Tripodi GG, Cianci V, Aguglia U. Botulism-induced unilateral submandibular sialoadenitis: a case report. Neurol Sci 2013; 34:2225–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kotan D, Aygul R, Ceylan M, Yilikoglu Y. Clinically and electrophysiologically diagnosed botulinum intoxication. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr.01.2012.5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pender RA, Escutin RO, Peterson GW. Case report with sequential nerve conduction studies: a very old patient with atypical foodborne botulism type a with pupil sparing treated with botulinum antitoxin. Toxicon 2013; 68:75. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zhang J-C, Xie F, Sun L. Type E botulism associated with crude beef: a case report. Afr J Microbiol Res 2013; 7:3566–8. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Arora A, Sharma CM, Kumawat B, Khandelwal D. Rare presentation of botulism with generalized fasciculations. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2014; 4:56–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Anniballi F, Chironna E, Astegiano S et al. Foodborne botulism associated with home-preserved turnip tops in Italy. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2015; 51:60–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.