Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

The authors' center recently changed their pretransfusion testing protocol from “conventional” type and screen (TS) with anti-human globulin (AHG) crossmatch (Policy A) to TS with immediate-spin (IS) crossmatch (Policy B). Red blood cell (RBC) units were issued after compatible IS crossmatch as and when required instead of AHG crossmatch. This study was conducted to compare the effects of change of policy from A to B over 1-year period on crossmatch-to-transfusion (C/T) ratio, RBC issue turnaround time (TAT), outdating of RBC, man-hours consumption, and monetary savings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This was a comparative, prospective study conducted by the Department of Transfusion Medicine of a tertiary hospital-based blood bank in Northern India. The Policy B was implemented in the department from January 2014. Relevant retrospective data for comparison of the previous 1 year, when Policy A was practiced, were derived from hospital information system.

RESULTS:

23909 and 24724 RBC units transfused to patients admitted to the hospital during respective 1-year period of practice for Policy A and B. There was significant reduction in C/T ratio (1.94 vs. 1.01) and RBC issue TAT (79 vs. 65 min) with Policy B. Expiry due to outdating reduced (37 vs. zero) along with man-hours (16% reduction) and monetary (33% reduction) savings.

CONCLUSION:

Use of 'TS with IS crossmatch' policy provides multiple advantages to all the stakeholders; blood banker, clinician, patient, and the hospital management.

Keywords: Blood transfusion practice, crossmatch-to-transfusion ratio, turnaround time, type and crossmatch, type and screen

Introduction

Most blood banks in India follow type and crossmatch (TXM) policy, wherein they perform an anti-human globulin (AHG) crossmatch and reserve stipulated number of red blood cell (RBC) units for a specific patient usually for 48–72 h.[1] These units are then issued as and when actual need arises, for example, surgical blood loss, postoperative blood loss, and symptomatic anemia. This reservation of the blood unit for a particular patient prohibits the blood bank to issue that unit to another patient in need. Reservation also results in additional inventory management as all the RBC units reserved have to be labeled and segregated. Blood units not issued to patients during the stipulated time period are “unreserved” and taken back into the main inventory. Thus, risk of blood unit expiration as a result of outdating also increases due to inadvertent repeated reservation and unreservation. Further, large number of unnecessary crossmatch tests performed also means unnecessary workforce and reagent wastage. Thus, TXM policy with AHG crossmatch and reservation results in increased burden on blood resource and finances. Several blood banks continue to perform AHG crossmatch despite introducing type and screen (TS) as a part of their pretransfusion testing protocol.

In comparison, TS policy with immediate-spin (IS) crossmatch provides similar immunohematological safety[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] with possibility of better crossmatch-to-transfusion (C/T) ratio and decreased turnaround time (TAT) for the issue of blood units. Since there is no reservation of RBC units in the TS policy and RBCs are cross-matched and issued as and when required by the patient, outdating of RBC units decreases. This results in better workforce utilization and greater monetary savings. Studies conducted by Alavi-Moghaddam et al.,[12] Chow,[13] Alexander and Henry,[7] and Kuriyan et al.[14] have concluded that the implementation of TS policy has been proven to be efficient and beneficial to the transfusion practice in their respective hospitals.

The authors' center recently changed their pretransfusion testing protocol from “conventional” TS with AHG crossmatch (Policy A) to TS with immediate-spin (IS) crossmatch (Policy B). Authors demonstrated that Policy B has safety comparable to Policy A.[15] Policy B was implemented after this publication[15] and was being followed for the last 1 year. These “1-year” data were compared with the retrospective “1-year Policy A” data with respect to C/T ratio, TAT, savings in blood resource, finances, and workforce to quantify the efficiency and advantages.

Materials and Methods

Study design and settings

This was prospective, longitudinal study conducted in the Department of Transfusion Medicine of a tertiary care hospital in North India. The data was collected prospectively for 1 year (January–December 2014) after the implementation of the TS policy with IS (Policy B). This prospective data was compared with retrospective data collected for the TS policy with AHG crossmatch (Policy A) during the previous year (January–December 2013).

Ethical clearance

The ethics committee of the institution approved the study.

Parameters of comparison

-

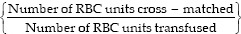

C/T:

-

TAT:

{Time of issue − time of requisition}

Steps in Policy A included blood group of the patient and donor, AHG crossmatch, labeling and reservation of compatible RBC unit(s), and finally issue of the unit at the time of requirement. Steps in Policy B included blood group of the patient and donor, followed by IS crossmatch at the time of issue of RBC unit.

-

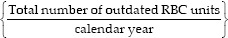

RBC outdating

This was calculated as number of RBC units discarded due to outdating of their shelf life during each study period.

-

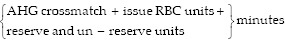

Man-hours utilization

Policy A man–hours=

Policy B man–hours=

{IS crossmatch + issue RBC units} minutes

These time durations in minutes were recorded by conducting “time motion” studies over a period of 1 week three times over and the mean was calculated. Total man-hours consumed were calculated by multiplying this mean time per process with total number of RBC units issued in each study period.

-

Financial calculation: Financial calculation was done for each study period as follows:

{Cost of consumables and reagents per crossmatch × total crossmatches}.

Results

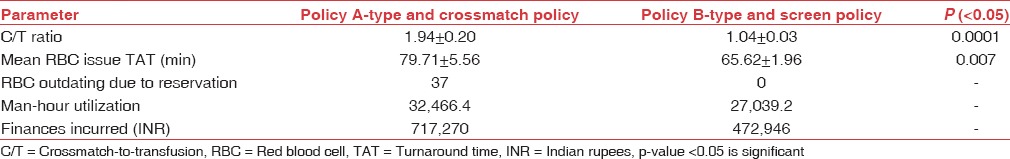

23909 and 24724 RBC units were issued and transfused to patients admitted to the hospital during respective 1-year period of practice for Policy A and B. Table 1 compares and contrasts the two policies with regard to parameters of comparison.

Table 1.

Comparison between Policy A and Policy B

Discussion

TS policy with IS crossmatch (Policy B) is as safe as TS policy with conventional AHG crossmatch (Policy A), and this has been proven multiple times by various authors.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Present authors have also published on safety of TS policy with IS crossmatch.[15] The authors would wish to discuss other advantages of this policy with respect to decreased C/T ratio, decreased issue TAT, decreased outdating of RBC units, man-hours consumption, and monetary savings. It is also important to understand that several of these benefits accrue differently for stakeholders; blood banker, clinician, patient, and the hospital management.

Reduced crossmatch-to-transfusion ratio

C/T ratio reduced from 1.94 to 1.04 in the present study. Similar results were reported by Chow[13] where C/T ratio reduced from 2.9 to 1.3 and Alavi-Moghaddam et al.,[12] who demonstrated reduction in C/T ratio from 1.41 to 1.13 after the implementation of TS protocol. While in earlier Policy A, several units were cross-matched and reserved for the patient for possible use; Policy B did not require any reservation. Since the crossmatch was performed just before transfusion, the number of unnecessary cross-matches came down dramatically. It was only in very few cases, e.g., cancellation of surgery or fever, that the crossmatch units were not transfused in Policy B.

Reduced red blood cell issue turnaround time

The mean TAT to issue RBC unit with Policy B was 65.62 min as compared to 79.71 min with earlier Policy A. This was statistically significant reduction in TAT. Other studies by Alavi-Moghaddam et al.[12] and Chow[13] also demonstrated significantly reduced TAT after implementation of TS protocol. The reduction in TAT is obvious across various studies; however, it does not match since workers defined TAT differently. This reduction in TAT for the issue of blood was especially useful for patients (and their physicians) in case of urgent blood requirement. This also diminished the “over-ordering” by the physicians for “just-in-case” scenarios.

Reduced outdating of red blood cell units

After implementation of Policy B, no RBC unit expired due to outdating during the study period. In comparison, 37 RBC units expired due to outdating during the Policy A study period. This meant a reduction of 0.14%. Chow[13] also reported a significant reduction of expiry of RBC units from 2.5% to 0.9% after implementation of TS policy in his hospital. Kuriyan et al.[14] also reported only 0.2% outdating of RBCs in their facility with TS policy over 3 years. Repeated “reservation-unreservation” during Policy A meant that some RBC units expired in transition.

Man-hours saved

The mean number of man-hours consumed during Policy B to process and issue RBC units was much less than what was consumed during the Policy A period. This reduction is explained by several reasons; (i) decreased number of RBC cross-matched, (ii) reduced time required for IS crossmatch (abbreviated) as compared to AHG crossmatch (complete), and (iii) obviating the need of daily “reservation-unreservation” of RBC units. The man-hours saved meant one technician being spared for 8-h shift and he/she could be utilized for other more useful blood bank tasks.

Monetary savings

In our settings, Policy B proved to be more economical than Policy A by 33%. Kuriyan et al.[14] also concluded that use of IS crossmatch instead of AHG crossmatch resulted in up to 30% savings in their study. Use of less costly column agglutination cards for IS crossmatch and lesser reagent (low ionic strength solution) usage coupled with lesser number of crossmatch performed was the main reason for monetary savings for the blood bank. Each unnecessary crossmatch that was not done also saved money for the hospital (and patients). Alexander and Henry[7] calculated that for every unnecessary AHG crossmatch not performed, the patient saved US $36. In the present study, we calculated that each unnecessary crossmatch not performed saved INR 28 to the patient.

Conclusion

Use of TS policy with IS crossmatch provides multiple advantages at times to one/few and at times to all the stakeholders; blood banker, clinician, patient, and the hospital management.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Walker RH, editor. Technical Manual. 11th ed. Bethesda, MD: American Association of Blood Banks; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberman HA, Barnes BA, Friedman BA. The risk of abbreviating the major crossmatch in urgent or massive transfusion. Transfusion. 1978;18:137–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1978.18278160574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer EA, Shulman IA. The sensitivity and specificity of the immediate-spin crossmatch. Transfusion. 1989;29:99–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1989.29289146847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heddle NM, O'Hoski P, Singer J, McBride JA, Ali MA, Kelton JG. A prospective study to determine the safety of omitting the antiglobulin crossmatch from pretransfusion testing. Br J Haematol. 1992;81:579–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb02995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinkerton PH, Coovadia AS, Goldstein J. Frequency of delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions following antibody screening and immediate-spin crossmatching. Transfusion. 1992;32:814–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32993110751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman IA, Odono V. The risk of overt acute hemolytic transfusion reaction following the use of an immediate-spin crossmatch. Transfusion. 1994;34:87–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34194098619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander D, Henry JB. Immediate-spin crossmatch in routine use: A growing trend in compatibility testing for red cell transfusion therapy. Vox Sang. 1996;70:48–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1996.tb01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee E, Redman M, Burgess G, Win N. Do patients with autoantibodies or clinically insignificant alloantibodies require an indirect antiglobulin test crossmatch? Transfusion. 2007;47:1290–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pathak S, Chandrashekhar M, Wankhede GR. Type and screen policy in the blood bank: Is AHG cross-match still required? A study at a multispecialty corporate hospital in India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:153–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.83242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhary R, Agarwal N. Safety of type and screen method compared to conventional antiglobulin crossmatch procedures for compatibility testing in Indian setting. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:157–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.83243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal A. Type and screen policy: Is there any compromise on blood safety? Transfus Apher Sci. 2014;50:271–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alavi-Moghaddam M, Bardeh M, Alimohammadi H, Emami H, Hosseini-Zijoud SM. Blood transfusion practice before and after implementation of type and screen protocol in emergency department of a university affiliated hospital in Iran. Emerg Med Int 2014. 2014:316463. doi: 10.1155/2014/316463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow EY. The impact of the type and screen test policy on hospital transfusion practice. Hong Kong Med J. 1999;5:275–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuriyan M, Fox E. Pretransfusion testing without serologic crossmatch: Approaches to ensure patient safety. Vox Sang. 2000;78:113–8. doi: 10.1159/000031160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari AK, Aggarwal G, Dara RC, Arora D, Gupta GK, Raina V. First Indian study to establish safety of immediate-spin crossmatch for red blood cell transfusion in antibody screen-negative recipients. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2017;11:40–4. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.200774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]