Abstract

Background:

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative saprophytic soil bacterium that causes melioidosis, a potentially fatal disease endemic in wet tropical areas. The currently available biochemical identification systems can misidentify some strains of B. pseudomallei. The aim of the present study was to identify the biochemical features of B. pseudomallei, which can affect its correct identification by Vitek 2 system.

Materials and Methods:

The biochemical patterns of 40 B. pseudomallei strains were obtained using Vitek 2 GN cards. The average contribution of biochemical tests in overall dissimilarities between correctly and incorrectly identified strains was assessed using nonmetric multidimensional scaling.

Results:

It was found (R statistic of 0.836, P = 0.001) that a combination of negative N-acetyl galactosaminidase, β-N-acetyl glucosaminidase, phosphatase, and positive D-cellobiase (dCEL), tyrosine arylamidase (TyrA), and L-proline arylamidase (ProA) tests leads to low discrimination of B. pseudomallei, whereas a set of positive dCEL and negative N-acetyl galactosaminidase, TyrA, and ProA determines the wrong identification of B. pseudomallei as Burkholderia cepacia complex.

Conclusion:

The further expansion of the Vitek 2 identification keys is needed for correct identification of atypical or regionally distributed biochemical profiles of B. pseudomallei.

Keywords: Biochemical identification, Burkholderia cepacia, Burkholderia pseudomallei, nonmetric multidimensional scaling, Vitek 2

INTRODUCTION

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a Gram-negative saprophytic soil β-proteobacterium that causes melioidosis, a severe disease of humans and animals. Melioidosis is endemic in a number of areas of Southeast Asia, Northern Australia, the Pacific, Central and South America, and the Caribbean.[1] According to recent estimates, the global burden of melioidosis is about 165,000 human cases per year, and an infection is probably endemic in at least 79 countries.[2]

Melioidosis is acquired more often through contact with contaminated soil and water by percutaneous inoculation. The human cases are often spatially and temporally clustered, following the severe weather events such as heavy rains and flooding.[3] Clinical manifestation of melioidosis varies widely from asymptomatic disease to rapidly progressive pneumonia and sepsis. The symptoms often are very similar to other both infectious and non-infectious diseases-tuberculosis, mycosis, sarcoidosis, cancer, which makes the differential clinical diagnosis of melioidosis quite a challenge.[4,5] Treatment of melioidosis is hampered by an intrinsic resistance of B. pseudomallei to various antimicrobials.[3,6]

The correct laboratory diagnosis of melioidosis is essential for a favorable outcome but can be difficult. B. pseudomallei is usually poorly isolated from clinical specimens and may not be correctly identified when isolated.[5,7] Routinely used serological tests generally are not sufficiently specific or sensitive. Although laboratory diagnosis of melioidosis has advanced using of more sensitive and rapid tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), DNA sequencing, and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry,[8] the correct identification of B. pseudomallei isolates through conventional bacteriologic scheme is very important, especially in clinical microbiology laboratories in nonendemic areas where clinical suspicion is insufficient.

Due to duration and complexity of routine bacteriological identification of B. pseudomallei,[5,6] the suitability of various commercial biochemical tests has been studied for a long time. As has been noted repeatedly, the currently available biochemical systems can misidentify some strains of B. pseudomallei as Chromobacterium violaceum or Burkholderia cepacia complex.[7,9,10,11,12] A particular problem is associated with misidentification of B. pseudomallei as B. cepacia by Vitek 2 analyzer (bioMérieux) widely used in clinical microbiology laboratories.[12,13]

The aim of this study was to identify the biochemical features, which can cause an incorrect identification of B. pseudomallei by Vitek 2 system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, culture condition, and identification on Vitek 2 platform

Forty strains of B. pseudomallei studied in this work are listed in Table 1. All strains were confirmed by specific PCR, DNA sequencing, and conventional bacteriologic method. The strains were subcultured on LB agar (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, India) for 24 hours at 37°C before testing on Vitek 2. The GN cards (bioMérieux) were used for analysis according to the manufacturer's instructions.

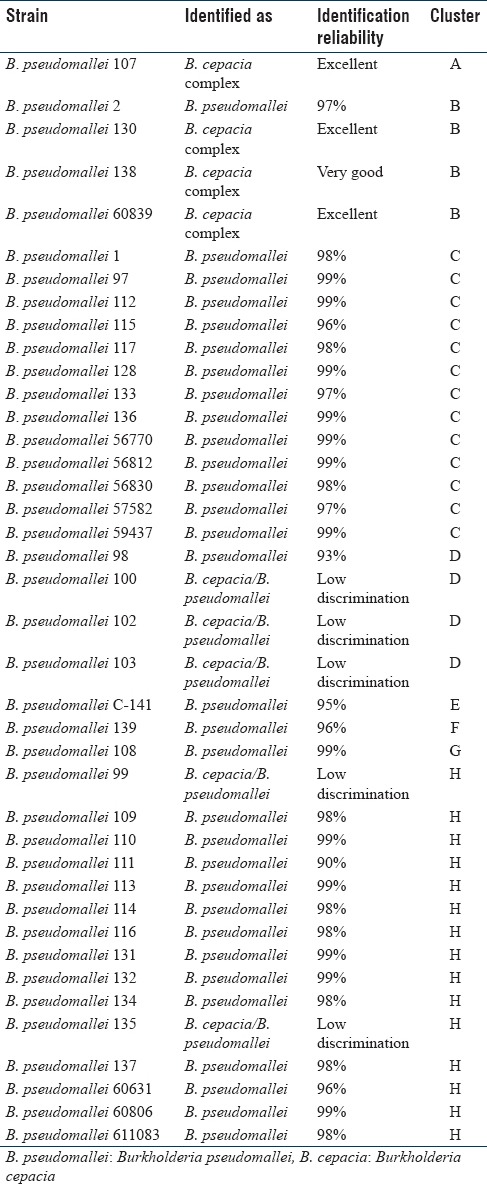

Table 1.

Identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei strains by Vitek 2 and nonmetric multidimensional scaling clustering of biochemical profiles

Comparative analysis of biochemical profiles

The comparative analysis of binary biochemical profiles (0-lack of the feature, 1-positive) was carried using PRIMER package version 7.0.10 (Primer-E Ltd., Plymouth Marine Laboratory, United Kingdom). The clustering of the strains was performed using nonmetric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) on Euclidean distances similarity matrix of biochemical profiles. The reliability of biochemical patterns difference between properly and incorrectly identified strains was assessed using nonparametric analysis of similarity (ANOSIM). The ANOSIM percentage was used to evaluate an average contribution of each biochemical test in overall dissimilarity between clusters.

RESULTS

Biochemical identification

The most of studied B. pseudomallei strains (77.5% of the total) were identified correctly with the reliability of 90%–99% [Table 1]. Five strains (12.5%) were identified at low discrimination as B. cepacia complex/B. pseudomallei with the recommendation to use additional differentiating tests. Four strains (10%) were identified as B. cepacia complex with the conclusion “very good identification” (1 strain) and “excellent identification” (3 strains).

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis

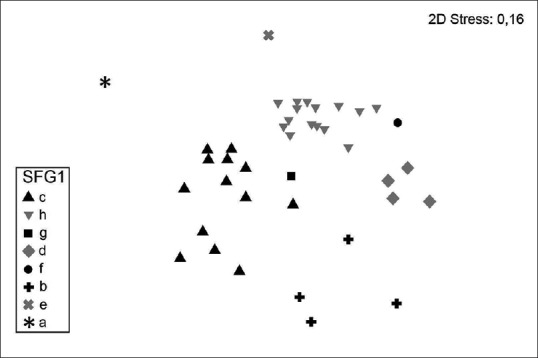

The nMDS allowed to group the strains of B. pseudomallei into 8 clusters [Figure 1]. The clusters A, F, E, and G included one strain each. Three strains identified incorrectly as B. cepacia and one correctly identified strain (“excellent identification”) were included in cluster B. Thirteen strains with high probability of identification (97%–99%) were combined in cluster C. The cluster H proved to be the most extensive, which included 11 strains with “excellent identification,” 2 strains with “good identification,” and 2 strains at low discrimination. The cluster D includes 4 strains, of which 3 are at low discrimination and 1-with a high probability of identification (93%) [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling ordination on the euclidean distance similarity matrix of the Vitek 2 biochemical profile of 40 Burkholderia pseudomallei strains identified as Burkholderia pseudomallei and misidentified as Burkholderia cepacia, or strains at low discrimination

The contribution of individual biochemical tests in misidentification of Burkholderia pseudomallei

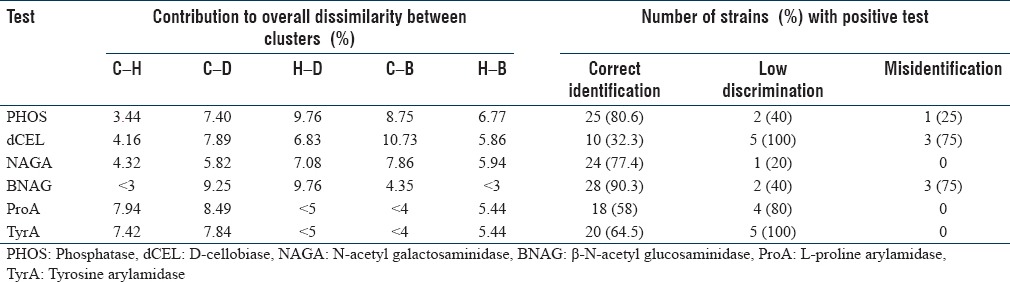

The ANOSIM showed statistically significant differences in biochemical patterns of correctly and incorrectly identified strains (R statistic of 0.836, P = 0.001). The results estimate the average contribution of biochemical tests in overall dissimilarity between biochemical profile clusters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The average contribution of selected biochemical tests in overall dissimilarity between clusters of the strains

It seems clear that the reliability of identification decreased in case of absence of phosphatase (PHOS), β-N-acetyl glucosaminidase (BNAG), N-acetyl galactosaminidase (NAGA) and the presence of D-cellobiase (dCEL), L-proline arylamidase (ProA), and tyrosine arylamidase (TyrA) activities. Thus, in strains identified at low discrimination, the dCEL and TyrA tests were positive in 100% of cases, and ProA in 80% of cases. At the same time, the NAGA (80% of cases), BNAG, and PHOS (60% of cases) tests were negative [Table 2].

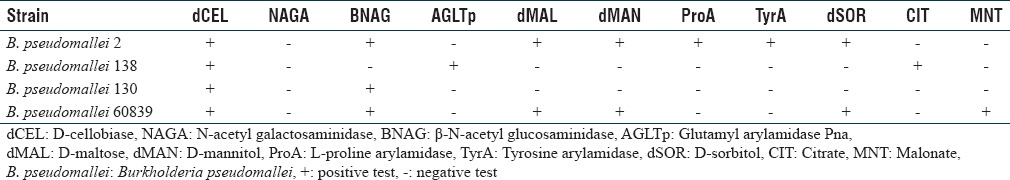

The comparison of biochemical profiles included in cluster B (B. pseudomallei 2 identified with the reliability of 97%, and B. pseudomallei 130, 138, and 60839 misidentified as B. cepacia) showed positive dCEL and negative PHOS in all cases. The BNAG test was negative in only one (B. pseudomallei 138) of the three wrongly identified strains [Table 3]. The glutamyl arylamidase Pna, D-maltose, D-mannitol (dMAN), D-sorbitol (dSOR), citrate, and malonate utilization tests also varied, but any consistent patterns affecting identification have not been revealed in these cases. The key tests in this cluster were ProA and TyrA, which were positive in correctly identified strain, similar to 58% and 64.5% of all correctly identified strains, respectively, whereas all misidentified strains were negative for these biochemical features [Table 2].

Table 3.

The biochemical tests varied in strains constituting cluster B

DISCUSSION

The troubles on the correct identification of B. pseudomallei by various biochemical systems have been described repeatedly. According to different data, the reliability of API 20NE (bioMérieux) manual system for identification of B. pseudomallei varied significantly,[7,9,10,14] that, combined with a long operating time, not allows to consider this system as the best option for B. pseudomallei identification.

A part of various automated systems does not include a representative set of biochemical profiles for B. pseudomallei,[15] whereas others give mainly low discrimination for B. pseudomallei or misidentification as B. cepacia.[9]

Widely used Vitek 2 system gives the most stable identification results, especially with the use of colorimetric-based GN cards.[16] Nevertheless, the identification accuracy still varies considerably for B. pseudomallei strains of different geographical origin.[11] An important task is to establish exactly what biochemical tests due to its variability lead to misidentification or low discrimination of B. pseudomallei.

As revealed by Lowe et al., the uncertain results of several biochemical tests (D-cellobiose, D-glucose, dMAN, dSOR, gamma-glutamyltransferase, L-lysine arylamidase, and phosphatase) would result in a reduction of Vitek 2 discriminating ability for B. pseudomallei.[10] More recently, Podin et al. noted that in particular, two enzymatic tests, BNAG and NAGA, were distinct between correctly and misidentified B. pseudomallei isolates.[11]

The results of the present study showed that a set of negative NAGA, BNAG, PHOS and positive dCEL, TyrA, ProA tests lead to low discrimination of B. pseudomallei, and the presence of dCEL activity combined with negative tests for NAGA, TyrA, and ProA would result in misidentification of B. pseudomallei as B. cepacia complex.

CONCLUSION

The obtained results demonstrate the effect of the variability of several biochemical features on the accuracy of B. pseudomallei identification. The data mentioned above demonstrate the need of further expansion of the Vitek 2 identification keys for atypical or regionally distributed biochemical profiles of B. pseudomallei. Also important, that clinicians and diagnostic laboratories stuff should be aware on the possibility of misidentification of B. pseudomallei as B. cepacia using automated biochemical identification systems.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Currie BJ, Kaestli M. Epidemiology: A global picture of melioidosis. Nature. 2016;529:290–1. doi: 10.1038/529290a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limmathurotsakul D, Golding N, Dance DA, Messina JP, Pigott DM, Moyes CL, et al. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:15008. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng AC, Currie BJ. Melioidosis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:383–416. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.383-416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limmathurotsakul D, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis: A clinical overview. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:125–39. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilad J, Schwartz D, Amsalem Y. Clinical features and laboratory diagnosis of infection with the potential bioterrorism agents Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei. Int J Biomed Sci. 2007;3:144–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1035–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inglis TJ, Chiang D, Lee GS, Chor-Kiang L. Potential misidentification of Burkholderia pseudomallei by API 20NE. Pathology. 1998;30:62–4. doi: 10.1080/00313029800169685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau SK, Sridhar S, Ho CC, Chow WN, Lee KC, Lam CW, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of melioidosis: Past, present and future. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015;240:742–51. doi: 10.1177/1535370215583801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiratisin P, Santanirand P, Chantratita N, Kaewdaeng S. Accuracy of commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei versus Burkholderia cepacia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe P, Engler C, Norton R. Comparison of automated and nonautomated systems for identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4625–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4625-4627.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Podin Y, Kaestli M, McMahon N, Hennessy J, Ngian HU, Wong JS, et al. Reliability of automated biochemical identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei is regionally dependent. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3076–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01290-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissert C, Dollenmaier G, Rafeiner P, Riehm J, Schultze D. Burkholderia pseudomallei misidentified by automated system. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1799–801. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.081719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zong Z, Wang X, Deng Y, Zhou T. Misidentification of Burkholderia pseudomallei as Burkholderia cepacia by the VITEK 2 system. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1483–4. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.041525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deepak RN, Crawley B, Phang E. Burkholderia pseudomallei identification: A comparison between the API 20NE and VITEK2GN systems. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(Suppl 1):S42–4. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(08)70012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh TH, Yong Ng LS, Foon Ho JL, Sng LH, Wang GC, Tzer Pin Lin RV, et al. Automated identification systems and Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1809. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1809.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe P, Haswell H, Lewis K. Use of various common isolation media to evaluate the new VITEK 2 colorimetric GN card for identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:854–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.854-856.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]