Abstract

BACKGROUND

Successful cryopreservation of oocytes and embryos is essential not only to maximize the safety and efficacy of ovarian stimulation cycles in an IVF treatment, but also to enable fertility preservation. Two cryopreservation methods are routinely used: slow-freezing or vitrification. Slow-freezing allows for freezing to occur at a sufficiently slow rate to permit adequate cellular dehydration while minimizing intracellular ice formation. Vitrification allows the solidification of the cell(s) and of the extracellular milieu into a glass-like state without the formation of ice.

OBJECTIVE AND RATIONALE

The objective of our study was to provide a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes following slow-freezing/thawing versus vitrification/warming of oocytes and embryos and to inform the development of World Health Organization guidance on the most effective cryopreservation method.

SEARCH METHODS

A Medline search was performed from 1966 to 1 August 2016 using the following search terms: (Oocyte(s) [tiab] OR (Pronuclear[tiab] OR Embryo[tiab] OR Blastocyst[tiab]) AND (vitrification[tiab] OR freezing[tiab] OR freeze[tiab]) AND (pregnancy[tiab] OR birth[tiab] OR clinical[tiab]). Queries were limited to those involving humans. RCTs and cohort studies that were published in full-length were considered eligible. Each reference was reviewed for relevance and only primary evidence and relevant articles from the bibliographies of included articles were considered. References were included if they reported cryosurvival rate, clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), live-birth rate (LBR) or delivery rate for slow-frozen or vitrified human oocytes or embryos. A meta-analysis was performed using a random effects model to calculate relative risk ratios (RR) and 95% CI.

OUTCOMES

One RCT study comparing slow-freezing versus vitrification of oocytes was included. Vitrification was associated with increased ongoing CPR per cycle (RR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.05–7.51; P = 0.039; 48 and 30 cycles, respectively, per transfer (RR = 1.81, 95% CI 0.71–4.67; P = 0.214; 47 and 19 transfers) and per warmed/thawed oocyte (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.02–1.28; P = 0.018; 260 and 238 oocytes). One RCT comparing vitrification versus fresh oocytes was analysed. In vitrification and fresh cycles, respectively, no evidence for a difference in ongoing CPR per randomized woman (RR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.87–1.21; P = 0.744, 300 women in each group), per cycle (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.86–1.18; P = 0.934; 267 versus 259 cycles) and per oocyte utilized (RR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.82–1.26; P = 0.873; 3286 versus 3185 oocytes) was reported. Findings were consistent with relevant cohort studies.

Of the seven RCTs on embryo cryopreservation identified, three met the inclusion criteria (638 warming/thawing cycles at cleavage and blastocyst stage), none of which involved pronuclear-stage embryos. A higher CPR per cycle was noted with embryo vitrification compared with slow-freezing, though this was of borderline statistical significance (RR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.00–3.59; P = 0.051; three RCTs; I2 = 71.9%). LBR per cycle was reported by one RCT performed with cleavage-stage embryos and was higher for vitrification (RR = 2.28; 95% CI: 1.17–4.44; P = 0.016; 216 cycles; one RCT). A secondary analysis was performed focusing on embryo cryosurvival rate. Pooled data from seven RCTs (3615 embryos) revealed a significant improvement in embryo cryosurvival following vitrification as compared with slow-freezing (RR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.30–1.93; P < 0.001; I2 = 93%).

WIDER IMPLICATIONS

Data from available RCTs suggest that vitrification/warming is superior to slow-freezing/thawing with regard to clinical outcomes (low quality of the evidence) and cryosurvival rates (moderate quality of the evidence) for oocytes, cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts. The results were confirmed by cohort studies. The improvements obtained with the introduction of vitrification have several important clinical implications in ART. Based on this evidence, in particular regarding cryosurvival rates, laboratories that continue to use slow-freezing should consider transitioning to the use of vitrification for cryopreservation.

Keywords: cryopreservation, vitrification, slow freezing, oocyte, embryo, blastocyst, World Health Organization

Introduction

Cryopreservation of gametes and embryos is an essential aspect of ART. Its widespread application has allowed increased safety and efficacy of IVF treatments. The proportion of cryopreserved embryo transfer cycles compared with fresh cycles is growing in Europe. Overall it has been estimated that cryopreserved cycles contributed to 32% of the transfers in 2011 compared to 28% in 2010. In some countries, such as Switzerland, Finland, Netherlands, Sweden and Iceland, the proportion of cryopreserved embryo transfers is higher than 50% (Kupka et al., 2016). The observed differences among European countries are mainly due to policies requiring lower transfer order which, in turn, have led to more supernumerary embryos available for cryopreservation (Coetsier and Dhont, 1998). The recent systematic application of cryopreservation for new indications such as cycle segmentation (i.e. planned freeze all) (Devroey et al., 2011), oocyte banking (Cobo et al., 2011a,2012) and pre-implantation genetic testing at the blastocyst stage (Schoolcraft et al., 2011) likely will contribute, in our opinion, to a further increase in the proportion of cryopreserved cycles in the near future.

Embryo cryopreservation has, however, generated ethical, moral and legal issues. Some countries have enacted specific laws that restrict (e.g. Germany, Switzerland, Austria) or even forbid (Italy with Law 40 in 2004) embryo cryopreservation. As an alternative and in accordance with the legal prohibition of embryo cryopreservation, oocyte cryopreservation had been introduced into routine practice in Italy (La Sala et al., 2006; Borini et al., 2006a,b, 2007; Levi Setti, 2006; De Santis et al., 2007; Ubaldi et al., 2010). Not until 2009 did the Italian Constitutional Court (151/2009) declare the constitutionality of embryo cryopreservation. Nevertheless, some couples are concerned about the disposition of cryopreserved embryos (Nachtigall et al., 2010) and therefore prefer to limit the number of oocytes inseminated, with cryopreservation of the remainder (Heng, 2007). Oocyte cryopreservation also has emerged as an important method for female fertility preservation for both medical and non-medical indications (reviewed in De Vos et al., 2014 and Stoop et al., 2014).

Since the first pregnancy and delivery with cryopreserved embryos (Trounson and Mohr, 1983; Zeilmaker et al., 1984), various protocols have been introduced that differ from each other regarding the type and concentration of cryoprotectants, equilibration timing, cooling rates and cryopreservation devices used. Two principal approaches for cryopreservation have been adopted: slow-freezing and vitrification (reviewed by Edgar and Gook, 2012).

Slow-freezing allows for cryopreservation to occur at a sufficiently slow rate to permit adequate cellular dehydration while minimizing intracellular ice formation. The first successful protocol applied in 1972 for mammalian embryo cryopreservation required a cooling rate of ~1°C/min to −70°C (Whittingham et al., 1972). Embryo cooling performed this way is referred to as equilibrium freezing (Mazur, 1990). Subsequently, slow-rate cooling was only applied to around −30°C (Willadsen, 1977). With this approach, intracellular water content was converted into small intracellular ice crystals or into a glass. To avoid extensive crystallization, a very rapid warming was required.

Although the first pregnancies with human cleavage-stage embryos were obtained with the use of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) as the cryoprotectant (Trounson and Mohr, 1983 and Zeilmaker et al., 1984) this approach was rapidly replaced.

For nearly 20 years the protocol combining 1.5 M propylene glycol (PROH) plus 0.1 M sucrose, as the permeable and non-permeable cryoprotectants, respectively, has been the most widely used (Lassalle et al., 1985; Testart et al., 1986). The freezing curve adopted requires the use of a programmable freezing machine designed to provide accurate and consistent cooling parameters. Briefly, the sample is exposed to a relatively rapid cooling rate of 2°C/min to around −7°C followed by a manual seeding to induce ice crystal formation in the solution. Then, a consistent slow cooling rate of 0.3–1.0°C/min is applied before the freezing device is plunged into liquid nitrogen after having reached temperatures around −40 to −70°C using the approach of Trounson and Mohr (1983) or Lassale et al., (1985), respectively. Modifications to the concentration of sucrose and the use of other cryoprotectants such as glycerol have been investigated for cryopreservation of oocytes, biopsied embryos and blastocysts (Cohen et al., 1985; Fabbri et al., 2001; Jericho et al., 2003; Veeck et al., 2004). Detailed analysis of biological principles and development of various slow-freezing procedures have been described previously (Leibo and Songstaken, 2002).

In contrast to slow-freezing, vitrification is a cryopreservation method that allows solidification of the cell(s) and the extracellular milieu into a glass-like state without the formation of ice. The most widely used vitrification method for mammalian embryos requires the use of high initial concentrations of cryoprotectants, low volumes and ultra-rapid cooling-warming rates. This approach was first introduced in human embryology for cleavage-stage embryos (Mukaida et al., 1998) and then for oocytes (Kuleshova et al., 1999) and pronuclear-stage embryos (Jelinkova et al., 2002; Selman and El-Danasouri, 2002). In the last 15 years several vitrification protocols have been described, which differ from one another in the type of cryoprotectants (Ethylene glycol [EG] and/or DMSO and/or PROH and sucrose and/or Ficoll and/or Trehalose), equilibration and dilution parameters, the carrier tools and the cooling, storage and warming methods (reviewed in Vajta and Nagy, 2006). To date the most commonly used protocol for both oocyte and embryo vitrification involves the combination of 15% DMSO, 15% EG and 0.5 M sucrose in a minimum volume (≤1 µl) (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b). Other fundamental aspects of the technique are related to the cooling and storing method. At present most embryos and oocytes are vitrified by exposing the sample to direct contact with liquid nitrogen (open system) to increase the cooling/warming rates and thus the efficiency of the procedure (Vajta et al., 2015). The ability to survive vitrification is in fact strictly dependent on the degree of cellular dehydration and on the rate of warming, rather than on the type and concentration of cryoprotectants used (Jin and Mazur, 2015). High cryosurvival rates of mouse oocytes and embryos have been recently obtained with the use of only non-permeating cryoprotectant and a relatively slow cooling rate, but combined with an ultra-rapid warming (Jin and Mazur, 2015). This study also demonstrates that the osmotic withdrawal of a very large proportion of intracellular water prior to cooling, and not the permeation of cryoprotectant in the cell, is the key for a successful vitrification (Jin and Mazur, 2015).

To avoid potential contamination during open system vitrification, sterile liquid nitrogen can be used (Vajta et al., 1998; Parmegiani et al., 2009). Alternatively, specific devices have been designed to avoid direct contact of the samples with the nitrogen either during vitrification (closed system) and/or during storage (Vajta et al., 1998; Kuleshova and Shaw 2000; Isachenko et al., 2006; Vanderzwalmen et al., 2009; Abdelhafez et al., 2011; Parmegiani, 2011). Of note, not all closed systems available on the market are completely free of any possible sources of contamination (Vajta et al., 2015). On the other hand, a lower degree of cooling/warming rate is generally associated with the use of these systems. To date, neither open nor closed systems have resulted in disease transmission during vitrification. However, to ensure biosafety during cryopreservation, the use of sterile approaches is recommended (Argyle et al., 2016), providing that adequate cooling and, particularly, warming rates are still guaranteed.

The objective of the present study was to compare slow-freezing/thawing versus vitrification/warming for cryopreservation of oocytes, embryos and blastocysts. RCTs and relevant observational cohort studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

This study was performed to support a prioritized clinical question and to provide a review of the evidence for debate and discussion during the consultation for the development of the World Health Organization (WHO) global guidelines: ‘Addressing evidence-based guidance on infertility diagnosis, management and treatment.’

Methods

Oocyte cryopreservation: study eligibility criteria

RCTs and well-designed cohort or case-control studies were included that compared outcomes following slow-freeze versus vitrification of mature i.e. metaphase II (MII) oocytes from women undergoing ART. Given the paucity of studies making direct comparisons between the two cryopreservation methods, studies comparing slow-freeze or vitrification to fresh oocytes (control group) were also included. Only trials reported in peer-reviewed full publications involving MII oocyte cryopreservation were included; abstracts were excluded. Data from these studies were used to assess the following outcomes: Clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), live-birth rate (LBR) and oocyte cryosurvival rate when reported.

Oocyte cryopreservation: study search methods

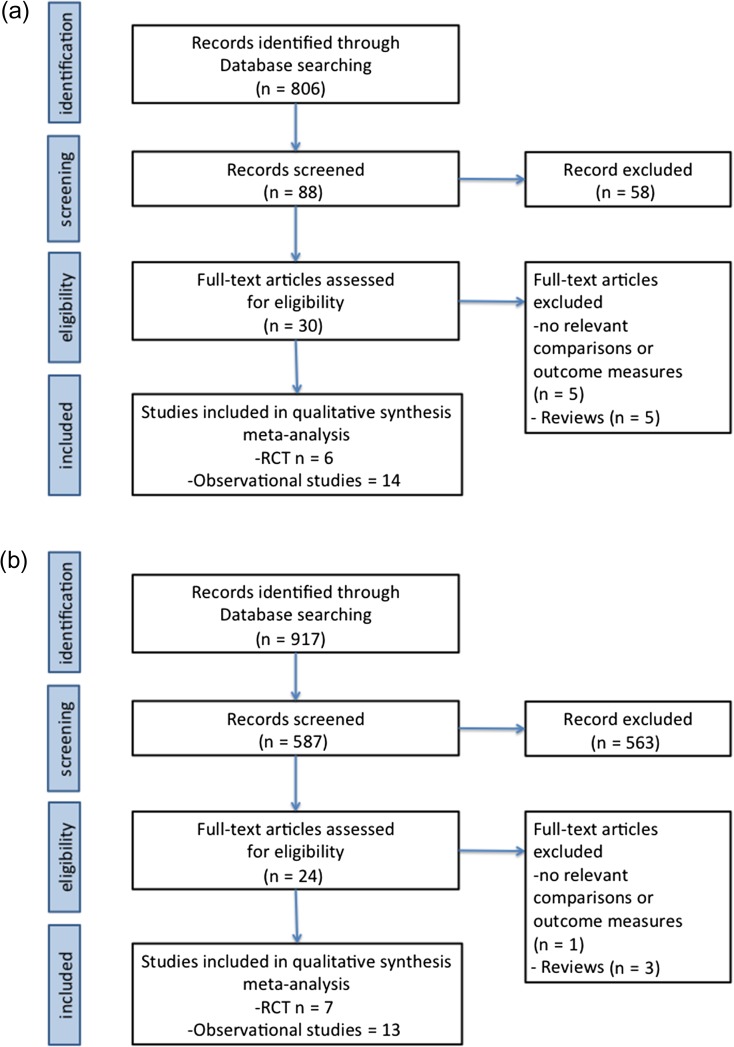

The searches for relevant studies were last performed and completed on 1 August 2016 by two review authors (AL, RM) using the following search terms: (oocyte(s) [tiab]) AND (vitrification[tiab] OR freezing[tiab] OR freeze[tiab]) AND (embryo quality[tiab] OR survival[tiab] OR pregnancy[tiab] OR birth[tiab]). The search was limited to human studies. Articles were also identified via snowball sampling by hand-searching references from systematic reviews. The search returned 806 records, of which 88 were screened manually for relevance. The information about potentially eligible studies was reported in a table describing the characteristics of the studies for assessing the reliability of the results. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were obtained and examined independently by the two different authors; disagreements as to study eligibility were resolved by discussion (all authors). A total of 20 references were included (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Flow charts for a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing slow-freezing versus vitrification of oocytes, embryos and blastocysts in ART. (a) search for relevant studies for oocytes slow-freezing and vitrification (b) search for relevant studies for pronuclear, cleavage-stage embryo and blastocyst slow-freezing and vitrification.

Oocyte cryopreservation: study descriptions

Slow-frozen versus vitrified oocytes: clinical outcomes and cryosurvival

One RCT was identified that randomized women to have an embryo transfer from MII oocytes that were either slow-frozen or vitrified (Smith et al., 2010). Characteristics of this study are described in Table I. A total of 230 patients with more than nine MII oocytes retrieved were allocated by random number generator to either slow-freezing or vitrification. This results in 30 cases of oocyte thawing and 48 cases of warming (average ages at oocyte retrieval: 32 ± 1 and 31 ± 1 years (mean + SD), respectively). LBRs were not reported. Ongoing CPRs were reported but not defined by minimum gestational age.

Table I.

Characteristics of the included RCTs comparing reproductive outcomes of slow-freezing versus vitrification.

| Authors (year) | Location | Study design | Cryopreservation protocols | Study group | N° | Control group | N° | Outcomes | Risk of bias | Journal: Impact factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balaban et al. (2008) | Turkey | Randomization of embryos | Vitrification 16%PrOH + 16% EG + 0.65 M sucrose + 10 mg/ml Ficoll- open system | Cleavage stage vitrification | 234 embryos | Cleavage stage slow-freezing | 232 embryos | cryosurvival rate, blastocyct formation | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, blinding | Human Reproduction: 4.621 |

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH–0.1 M Sucrose | ||||||||||

| Cao et al. (2009) | China | Randomization of sibling oocytes | Vitrification 15% EG + 15% PROH + 0.5 M sucrose – open system | Oocyte vitrificaiton | 292 oocytes | Oocyte slow-freezing | 123 oocytes | cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, blinding | Seminars in Reproductive Medicine: 2.113 |

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH + 0.3 M sucrose | ||||||||||

| Cobo et al. (2010) | Spain | Randomization of patients | Vitrification 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5 M sucrose – open system | Oocyte vitrification | 295 cycles | Oocyte fresh | 289 cycles | CPR, cryosurvival rate | No serious risk of bias | Human Reproduction: 4.621 |

| Debrock et al. (2015) | Belgium | Randomization of patients | Vitrification 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5 M sucrose – closed system | Cleavage stage vitrification | 121 cycles | Cleavage stage slow-freezing | 85 cycles | CPR, LBR, cryosurvival rate | No serious risk of bias | Human Reproduction: 4.621 |

| 200 embryos | ||||||||||

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH − 0.1 M Sucrose | 217 embryos | |||||||||

| Fasano et al. (2014) | Belgium | Randomization of embryos | Vitrification 20% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5 M sucrose – closed system | Cleavage stage vitrification | 516 cycles | Cleavage stage slow-freezing | 260 cycles | CPR, LBR, cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, and blinding | Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics: 1.772 |

| 660 embryos | 395 embryos | |||||||||

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH − 0.1 M Sucrose | ||||||||||

| Huang et al. (2005) | Taiwan | Randomization of embryos | Vitrification 20% EG + 20% DMSO and 0.5 M sucrose – open system | Blastocyst vitrification | 81 embryos | Blastocyst slow-freezing | 72 embryos | cryosurvial rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, blinding | Human Reproduction: 4.621 |

| Slow-freezing: 5% glycerol + 9% glycerol 0.2 M sucrose | ||||||||||

| Kim et al. (2000) | USA | Randomization of embryos | Vitrification 5.5 M EG + 1 M sucrose | Blastocyst vitrification | 42 cycles | Blastocyst slow-freezing | 216 cycles | CPR, cryosurvival rate | Unclear risk of bias related to random sequence generation, allocation of concealment acceptable, and blinding | Fertility and Sterility: 4.426 |

| Slow freezing: 5% glycerol and 9% glycerol + 0.2 M sucrose | 141 embryos | 790 embryos | ||||||||

| Paffoni et al. (2008) | Italy | Randomization of sibling oocytes | Vitrification 15% DMSO, 15% EG, and 0.5 M sucrose – closed system | Oocyte vitrification | 90 oocytes | Oocyte slow-freezing | 90 oocytes | Cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, blinding | Reproductive Sciences: 2.429 |

| Slow freezing: 1.5 mol/L PROH and 0.3 mol/L sucrose | ||||||||||

| Parmegiani et al. (2011) | Italy | Randomization of sibling oocytes | Vitrification 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5 M sucrose – open system | Oocyte vitrification | 168 oocytes | Oocyte Fresh | 120 oocytes | Cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, and blinding | RBM online:2.796 |

| Rama Raju et al. (2005) | India | Randomization of embryos | Vitrification 40% EG + 0.6 M sucrose – open system | Cleavage stage vitrification | 84 cycles | Cleavage stage slow-freezing | 80 cycles | CPR, cryosurvival rate | Unclear risk of bias related to random sequence generation, allocation of concealment acceptable, and blinding | RBM online:2.796 |

| 127 embryos | ||||||||||

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH- 0.1 M Sucrose | 120 embryos | |||||||||

| Rienzi et al. (2010) | Italy | Randomization of sibling oocytes | Vitrification 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5 M sucrose – open system | Oocyte vitrification | 124 oocytes | Oocyte Fresh | 120 oocytes | Cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, and blinding | Human Reproduction: 4.621 |

| Smith et al. (2010) | USA | Randomization of patients | Vitrification 15% EG + 15% DMSO + 0.5 M sucrose – closed system | Oocyte vitrification | 48 cycles | Oocyte Fresh | 30 cycles | CPR, cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias: related to randomization method, lack of allocation concealment, lack of blinding | Fertility and Sterility: 4.621 |

| 349 oocytes | 238 oocytes | |||||||||

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH- 0.3 M Sucrose | ||||||||||

| Zheng et al. (2005) | China | Randomization of embryos | Vitrification 30% EG + 0.5 M sucrose – open system | Cleavage stage vitrification | 49 embryos | Cleavage stage slow-freezing | 52 embryos | cryosurvival rate | Serious risk of bias due to randomization method, concealment of allocation, and blinding | Human Reproduction: 4.621 |

| Slow-freezing: 1.5 M PROH- 0.1 M sucrose/0.2 M sucrose |

PrOH, 1,2-propanediol; EG, Ethylene Glycol; DMSO, Dimethyl sulfoxide; CPR, Clinical Pregnancy rate; LBR, Live-birth rate.

Two cohort studies were identified that compared CPRs from slow-frozen versus vitrified autologous oocytes (Fadini et al., 2009; Levi Setti et al., 2014). Oocyte cryopreservation was performed in these studies in an unselected population of infertile patients due to law restrictions (Law 40, 2004, Italy).

A secondary analysis was performed focusing on oocyte cryosurvival rate. One RCT (Smith et al., 2010), two RCTs where sibling oocytes were randomized, rather than patients, (Paffoni et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2009) and three cohort studies (Fadini et al., 2009; Grifo and Noyes, 2010; Levi Setti et al., 2016) were included.

Slow-frozen versus fresh oocytes: clinical outcomes

No RCTs were identified comparing outcomes following transfer of embryos from oocytes that were either slow-frozen or fresh. Five cohort studies were identified comparing outcomes following transfer of embryos derived from fresh or slow-frozen/thawed oocytes (Chamayou et al., 2006; Levi Setti et al., 2006; Borini et al., 2007; Borini et al., 2010; Virant-Klun et al., 2011).

Vitrified versus fresh oocytes: clinical outcomes

One RCT was identified that randomized 600 donor recipients to transfer of embryos either from fresh or vitrified/warmed oocytes (Cobo et al., 2010). Characteristics of this study are described in Table I. Ongoing clinical pregnancy at 10–11 weeks of gestation was reported; however, live-birth data were not reported.

Thirteen other studies were identified: five randomized sibling oocytes, rather than patients, to vitrification versus fresh treatments (Cobo et al., 2008; Rienzi et al., 2010; Parmegiani et al., 2011; Siano et al., 2013; Forman et al., 2012), and eight cohort studies (Antinori et al., 2007; Nagy et al., 2009; Almodin et al., 2010; Ubaldi et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Trokoudes et al., 2011; Sole et al., 2013; Doyle et al., 2016). Three sibling oocyte RCTs (Cobo et al., 2008; Siano et al., 2013; Forman et al., 2012) and two cohort studies (Nagy et al., 2009 and Doyle et al., 2016) were excluded from analysis due to study design (Forman et al., 2012) or data reporting issues (Cobo et al., 2008; Nagy et al., 2009; Siano et al., 2013; Doyle et al., 2016).

The remaining eight studies were grouped together for comparison of clinical outcomes following transfer of embryos arising from oocytes that were exclusively either vitrified or fresh. Five meta-analyses (Oktay et al., 2006; Cobo et al., 2011b; Cil et al., 2013; Glujovsky et al., 2014; Potdar et al., 2014) focusing on oocyte cryopreservation were reviewed.

Embryo cryopreservation: study eligibility criteria

RCTs and observational cohort studies were included that compared slow-freeze to vitrification of pronuclear embryos, cleavage-stage embryos or blastocysts from women undergoing ART. Only trials reported in peer-reviewed full publications were included; abstracts were excluded. The following outcomes were assessed: CPR, LBR and embryo cryosurvival rate, when reported.

Embryo cryopreservation: study search methods

The searches for relevant studies were last performed and completed on August first 2016 using the following search terms: (Pronuclear[tiab] OR Embryo[tiab] OR Blastocyst[tiab]) AND (vitrification[tiab] OR freezing[tiab] OR freeze[tiab]) AND (pregnancy[tiab] OR birth[tiab] OR clinical[tiab]). The search was limited to human studies. Articles were also identified by hand searching references from systematic reviews. The search returned 917 records, of which 587 were screened manually for relevance. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were obtained and examined independently by two different authors (RM, DK); disagreements as to study eligibility were resolved by discussion (all Authors). A total of 20 studies were included for this analysis, comparing outcomes following transfer of vitrified versus slow-frozen embryos (Fig. 1b).

Embryo cryopreservation: study descriptions

Vitrified versus slow-frozen embryos: clinical outcomes

Only one well-designed RCT comparing clinical outcomes following vitrification versus slow-freezing between randomized women rather than embryos was identified (Debrock et al., 2015). Two RCTs (Rama Raju et al., 2005 and Kim et al., 2000) comparing clinical outcomes between randomized embryos were also included. Characteristics of these studies are described in Table I. One additional RCT (Bernal et al., 2008) was excluded because clinical outcomes were incomplete. Moreover, a meta-analysis (AbdelHafez et al., 2010) focusing on clinical outcomes was reviewed. None of the included studies compared cryopreservation techniques at the pronuclear-stage. Two of the included RCTs were performed at the cleavage-stage (Rama Raju et al., 2005; Debrock et al., 2015) and one at blastocyst stage (Kim et al., 2000). The primary outcome measures chosen were CPR and LBRs.

Eleven observational studies reporting clinical pregnancy per cycle and/or per transfer of embryos at different stages of development were pooled and analyzed (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Stehilk et al., 2005; Liebermann and Tucker, 2006; Rezazadeh Valojerdi et al., 2009; Wilding et al., 2010; Sifer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Van Landuyt et al., 2013 and Liu et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Kaartinen et al., 2016). An additional two studies described by the authors as RCT's were not truly randomized studies and were therefore included in the analysis with observational studies (Li et al., 2007 and Summers et al., 2016).

LBR per cycle and/or per transfer was reported in six studies (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Wilding et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Van Landuyt et al., 2013; Kaartinen et al., 2016).

Slow-frozen versus vitrified embryos: survival

A secondary analysis was performed focusing on embryo cryosurvival rate. Seven RCTs (Kim et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2005; Rama Raju et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2005; Balaban et al., 2008; Fasano et al., 2014; Debrock et al.,2015) were included. Characteristics of these studies are described in Table I. Moreover, 12 observational studies (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Stehilk et al., 2005; Liebermann and Tucker, 2006; Li et al., 2007; Rezazadeh Valojerdi et al., 2009; Wilding et al., 2010; Sifer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Van Landuyt et al., 2013 and Liu et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Summers et al., 2016) and two meta-analyses comparing results obtained with vitrification/warming and slow-freezing/thawing (Loutradi et al., 2008; Kolibianakis et al., 2009) were identified.

Assessing the quality of each study

According to the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development (WHO, 2012) the quality of each study was assessed. In particular, each RCT was evaluated for the following factors: how randomization was performed, whether there was concealment of allocation, whether participants and personnel were blinded to the intervention and outcome, whether there was complete data reporting, whether an intention to treat analysis was performed and whether any other potential sources of bias existed (WHO, 2012). The overall risk of bias was classified as serious, not serious, or unclear and is presented in Table I for each randomized trial included. The risk of bias is considered serious for all observational studies given the high risk for selection bias and confounding inherent in these study designs.

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

Meta-analyses of studies were undertaken to estimate the pooled relative risk ratios (RR) of outcomes including CPR per cycle, CPR per transfer and cryosurvival of thawed/warmed oocytes or embryos. Statistical analyses and construction of forest and funnel plots were performed with Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA). RR and 95% CIs were calculated for each outcome. A random effects model was used for the meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed with the use of the I2 test. Publication bias was assessed by constructing funnel plots.

Assessment of the quality of the literature as a whole

According to the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development (WHO, 2012) used to guide methodology in this systematic review, the quality of the literature for each analysis was classified as high, moderate, low or very low. A grade of high indicates that further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate indicates that further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; low indicates that further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; very low indicates that any estimate of effect is very uncertain (WHO, 2012).

Factors used to determine the classification for any analysis took into account the following factors: study design, consistency of the results across the available studies, precision of the results (width of the CI), the directness or generalizability of the results across populations, and the likelihood of publications bias.

Results

Oocyte slow-freezing versus vitrification: clinical outcomes and oocyte cryosurvival

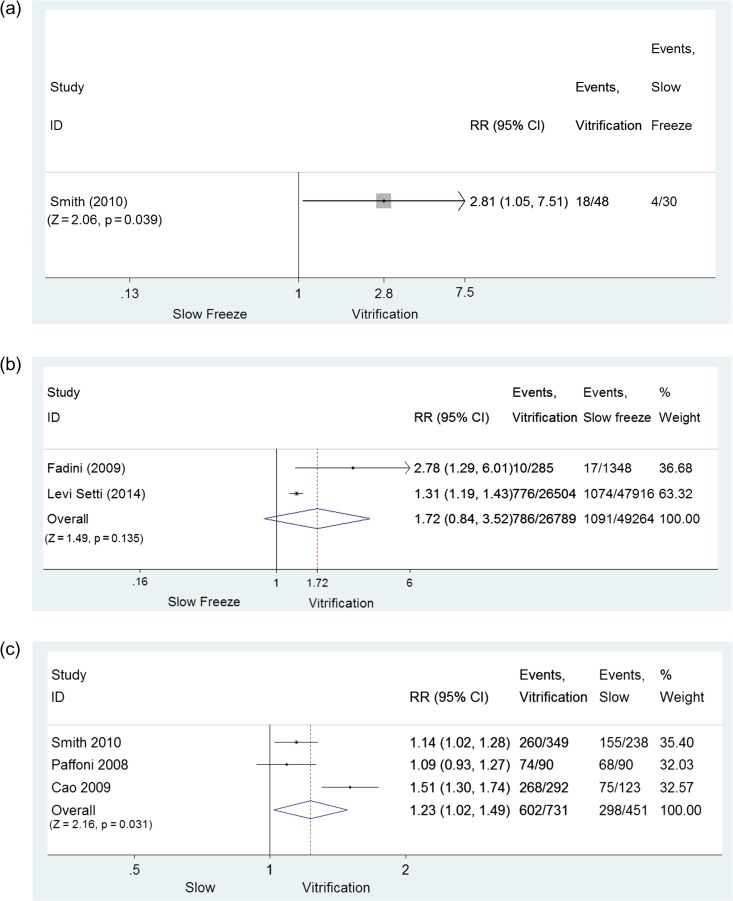

A single RCT (Smith et al., 2010) revealed evidence of a difference in favor of vitrification regarding ongoing pregnancy rate per cycle (RR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.05–7.51; P = 0.039; 48 and 30 cycles, vitrification versus slow-freezing, respectively; low quality evidence) (Fig. 2a) and per warmed/thawed oocyte (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.02–1.28; P = 0.018; 260 and 238 oocytes, vitrification versus slow-freezing, respectively; low quality evidence). Limited evidence demonstrated that clinical outcomes following vitrification versus slow-freezing were similar when ongoing pregnancy rate was expressed per embryo transfer (RR = 1.81, 95% CI: 0.71–4.67; P = 0.214; 47 and 19 transfers, vitrification versus slow-freezing, respectively; low quality evidence).

Figure 2.

Comparison of slow-freezing versus vitrification: oocytes. (a) Comparison based on CPR/cycle for oocytes: RCT; (b) Comparison based on CPR/cycle for oocytes: cohort studies; (c) Comparison based on oocyte cryosurvival rate: RCTs. CPR, clinical pregnancy rate.

In two cohort studies (Fadini et al., 2009; Levi Setti et al., 2014) the evidence also favored vitrification for CPR per cycle (RR = 1.72, 95% CI: 0.74–3.95; P = 0.212; 5460 and 9212 cycles, vitrification versus slow-freezing, respectively; I2 = 81.5%, very low quality evidence) (Fig. 2b), per transfer (RR = 1.55, 95% CI: 0.82–2.92; P = 0.180, two studies; I2 = 70.0%, very low quality evidence) and per warmed/thawed oocyte (RR = 1.72, 95% CI: 0.84–3.52; P = 0.135; 26789 and 49264 oocytes, vitrification versus slow-freezing, respectively; very low quality evidence). However, the differences were not statistically significant. Of note the CPR per cycle was relatively low in the unselected population of patients undergoing autologous oocyte cryopreservation due to law restrictions for both approaches, 11.8% and 14.4% for slow freezing and vitrification, respectively.

The superiority of vitrification over slow-freezing was also observed when cryosurvival rates of MII oocytes were compared. In three RCTs (Paffoni et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2010) MII cryosurvival rate was 82.3% (602/731) following vitrification/warming and 66.1% (298/451) following slow-freezing/thawing (RR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.02–1.49; P = 0.031; three studies; 1182 oocytes thawed; I2 = 82.9%, low quality evidence) (Fig. 2c). In the three cohort studies, cryosurvival rate after vitrification was also significantly higher than after slow-freezing (RR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.11–1.36, P < 0.001; three studies; 99 679 oocytes thawed; I2 = 91.6%, very low quality evidence) (Fadini et al., 2009; Levi-Setti et al., 2016; Grifo and Noyes, 2010).

Oocyte slow-freezing versus fresh oocytes: clinical outcomes

Analyses of the cohort studies (Chamayou et al., 2006; Borini et al., 2010; Virant-Klun et al., 2011) in which sibling oocytes were not randomized to be slow-frozen or used fresh revealed lower LBRs per cycle with slow-freezing (RR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.39–0.60; P < 0.0001; three studies; 990 and 2271 cycles; I2 = 0.0%, very low quality evidence) (Supplementary Fig. S1a), lower LBRs per transfer (RR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.44–0.68; P < 0.0001; three studies; 799 and 2046 cycles; I2 = 0.0%, very low quality evidence), and lower LBRs per utilized oocyte (RR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.21–0.32; P < 0.0001; three studies; 5513 and 6670 cycles; I2 = 0.0%, very low quality evidence) when slow-freeze was compared to fresh oocytes.

The CPR per cycle (RR = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.31–0.58; P < 0.0001; five studies, 1809 and 3323 cycles, slow-freezing versus fresh, respectively; I2 = 64.5%, very low quality evidence) (Supplementary Fig. S1b), the CPR per transfer (RR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.29–0.65, five studies; P < 0.0001; 1534 and 2989 transfers; I2 = 78.5%, very low quality evidence) and the CPR per utilized oocytes (RR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.25–0.35, four studies; 6600 and 9115 oocytes, slow-freezing versus, fresh, respectively; P < 0.0001; I2 = 4.8%, very low quality evidence) were all in favor of fresh oocytes as compared to slow-frozen oocytes (Chamayou et al., 2006; Levi Setti et al., 2006; Borini et al., 2007,2010; Virant-Klun et al., 2011). Each utilized slow-frozen oocyte had a 2.27% (150/6600) likelihood of resulting in a pregnancy in the population of women studied.

Oocyte vitrification versus fresh oocytes: clinical outcomes

Analysis of a single RCT (Cobo et al., 2010) revealed no evidence for a difference in ongoing CPR between the two groups when results were expressed per woman randomized (RR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.87–1.21; P = 0.744, 300 women in each group; moderate quality evidence), per cycle (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.86–1.18; P = 0.934; 267 versus 259 cycles vitrification versus fresh, respectively; moderate quality evidence) or per utilized oocyte (RR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.82–1.26; P = 0.873; 3286 versus 3185 oocytes, vitrification versus fresh, respectively; moderate quality evidence).

The combined analysis of the cohort studies and the RCTs in which sibling oocytes were randomized to be vitrified or used fresh (Sole et al., 2013; Parmegiani et al., 2011; Trokoudes et al., 2011) revealed no evidence of a difference between cycles using exclusively vitrified versus fresh oocytes for LBR per cycle (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.61–1.76, P = 0.892; three studies; 171 and 171 cycles, vitrification versus fresh, respectively; I2 = 52.3%; very low quality evidence) (Supplementary Fig. S2), LBR per oocyte utilized (RR = 2.35, 95% CI: 0.29–19.3, P = 0.427; two studies; 378 and 367 oocytes, vitrification versus fresh, respectively; I2 = 58.5%; very low quality evidence) (Parmegiani et al., 2011; Trokoudes et al., 2011), or LBR per transfer (RR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.64–1.88, P = 0.730; three studies; 166 and 170 transfers, vitrification versus fresh, respectively, I2 = 54.6%; very low quality evidence). The two groups were also similar for CPR per cycle (RR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.81–1.10; P = 0.457; eight studies; 526 and 892 cycles, vitrification versus fresh, respectively; I2 = 22.9%, very low quality evidence) (Sole et al., 2013; Antinori et al., 2007; Almodin et al., 2010; Rienzi et al., 2010; Ubaldi et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Parmegiani et al., 2011; Trokoudes et al., 2011); CPR per transfer (RR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.81–1.16; P = 0.714; seven studies, 477 and 754 transfers, vitrification versus fresh, respectively; I2 = 38.1%, very low quality evidence) (Sole et al., 2013; Antinori et al., 2007; Almodin et al., 2010; Ubaldi et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Parmegiani et al., 2011; Trokoudes et al., 2011); and CPR per oocyte utilized (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.57–2.69; P = 0.654; six studies; 1759 and 3832 oocytes, vitrification versus fresh, respectively; I2 = 89.5%, very low quality evidence) (Antinori et al., 2007; Almodin et al., 2010; Ubaldi et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Parmegiani et al., 2011; Trokoudes et al., 2011). Each utilized vitrified oocyte had an 8.36% (147/1759) likelihood of resulting in a pregnancy in the population of women studied.

Embryo slow-freezing versus vitrification

Slow-freezing versus vitrification: CPR

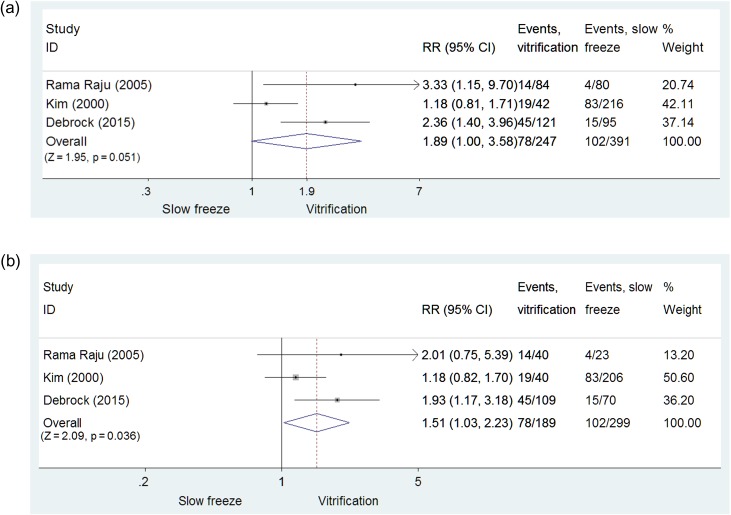

Given the limited number of RCTs available, results obtained in three RCTs with slow-freezing/thawing versus vitrification/warming for cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts (Kim et al., 2000; Rama Raju et al., 2005; Debrock et al., 2015) were pooled. Overall, 638 warming/thawing cycles (vitrification: n= 247; slow-freezing: n = 391) were included. Data from pronuclear-stage warming cycles were not available. A higher CPR per cycle was obtained with embryo vitrification compared with slow-freezing though this was of borderline statistical significance (RR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.00–3.58; P = 0.051, 638 cycles, three RCTs; I2 = 71.9%, low quality evidence, Fig. 3a). However, a significant difference in favor of vitrification was observed when CPR per embryo transfer was calculated (RR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.03–2.23; P = 0.036; 488 embryo transfers; three RCTs; I2 = 35%, low quality evidence, Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Comparison of slow-freezing versus vitrification: embryos. (a) Comparison of slow-freezing versus vitrification on CPR/cycle for cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts: RCTs; (b) Comparison of slow-freezing versus vitrification on CPR/embryo transfer for cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts: RCTs.

When pooling data from cohort studies (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Stehlik et al., 2005; Liebermann and Tucker, 2006; Li et al., 2007; Rezazadeh Valojerdi et al., 2009; Wilding et al., 2010; Sifer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Van Landuyt et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Kaartinen et al., 2016), there was a significantly higher CPR per cycle (Supplementary Fig. S3a), but not per transfer, with vitrification compared with slow-freezing (RR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.05–1.55; P = 0.015; eight observational studies; 8391 cycles; I2 = 76.5%, very low quality evidence and RR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.98–1.16; P = 0.16; 12 observational studies; 22 885 embryo transfers; I2 = 64.7%; very low quality evidence, respectively).

When restricting the analysis of observational studies to those including only cleavage-stage embryos (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Li et al., 2007; Rezazadeh Valojerdi et al., 2009; Wilding et al., 2010; Sifer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Van Landuyt et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Kaartinen et al., 2016), there was no statistically significant difference in CPR per cycle or CPR per transfer with vitrification compared with slow-freezing (RR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.00–1.55; P = 0.62; six observational studies; 7789 cycles; I2 = 78.8%, very low quality evidence and RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.95–1.16; P = 0.33; 10 observational studies; 17 448 embryo transfers; I2 = 67%; very low quality evidence, respectively).

When restricting the analysis of observational studies to those including only blastocyst stage embryos (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Stehlik et al., 2005; Liebermann and Tucker, 2006), there was no statistically significant difference in CPR per cycle or CPR per transfer with vitrification compared with slow-freezing (RR = 1.51, 95% CI: 0.69–3.29; P = 0.31; two observational studies; 602 cycles; I2 = 78.8%, very low quality evidence and RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.89–1.50; P = 0.27; three observational studies; 5437 embryo transfers; I2 = 61.8%; very low quality evidence, respectively).

Slow-freezing versus vitrification LBR

The LBR per cycle and per transfer was reported in only one RCT performed with embryos at the cleavage-stage (Debrock et al., 2015), with higher rates observed for vitrification (RR = 2.28; 95% CI: 1.17–4.44; P = 0.016; 216 cycles; low quality evidence and RR = 1.862 95% CI: 0.97–3.58; P = 0.062; 179 embryo transfers; low quality evidence, respectively).

Only three observational trials reported LBR per cycle (Wilding et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Van Landuyt et al., 2013) (Supplementary Fig. S3b) and six reported LBR per transfer (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Wilding et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Van Landuyt et al., 2013; Kaartinen et al., 2016). No differences were observed between vitrification and slow-freezing (RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.67–1.65; P = 0.831; 1621 cycles; I2 = 74.8%; very low quality evidence and RR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.91–1.18; P = 0.62; 14 996 embryo transfers; I2 = 45.8%; very low quality evidence, respectively).

When restricting the analysis of observational studies to those including only cleavage-stage embryos (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Li et al., 2007; Rezazadeh Valojerdi et al., 2009; Wilding et al., 2010; Sifer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Van Landuyt et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Kaartinen et al., 2016), there was no significant difference in LBR per cycle or LBR per transfer with vitrification compared with slow-freezing (RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.67–1.65; P = 0.83; three observational studies; 1621 cycles; I2 = 74.8%, very low quality evidence and RR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.87–1.20; P = 0.77; five observational studies; 10 153 embryo transfers; I2 = 52.7%; very low quality evidence, respectively).

When restricting the analysis of observational studies to those including only blastocyst stage embryos (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Stehlik et al., 2005; Liebermann and Tucker, 2006), there was no significant difference in LBR per cycle with vitrification compared with slow-freezing (RR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.87–1.40; P = 0.42; 1 observational study; 4843 cycles; very low quality evidence).

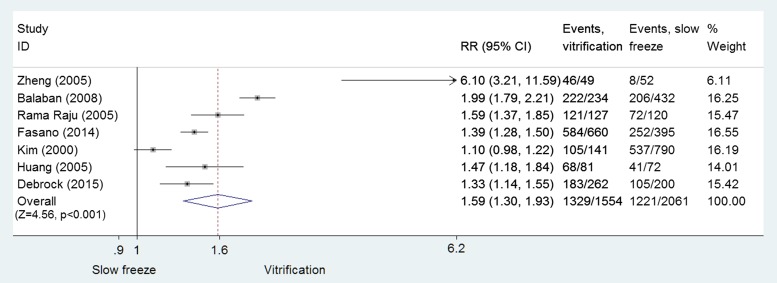

Slow-freezing versus vitrification: embryo cryosurvival

Data were pooled from the seven RCTs (Kim et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2005; Rama Raju et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2005; Balaban et al., 2008; Fasano et al., 2014; Debrock et al., 2015) involving 3615 cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts (slow-freezing: n = 2061; vitrification: n= 1554). The analysis revealed that vitrification was associated with a significant improvement in embryo cryosurvival (RR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.30–1.93; P < 0.001; I2 = 93%; moderate quality evidence) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of slow-freezing versus vitrification on cryosurvival rate for cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts: RCTs.

When restricted to cryosurvival of only cleavage-stage embryos, vitrification was superior to slow-freezing (RR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.39–2.18; 2531 embryos; P < 0.001; I2 = 92.2%; moderate quality evidence) (Rama Raju et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2005; Balaban et al., 2008; Fasano et al., 2014; Debrock et al., 2015). Post-warming cryosurvival rates of vitrified blastocysts were also higher than those observed with slow-freezing, but did not reach statistical significance (RR = 1.25: 95% CI: 0.93–1.67; P = 0.13; two RCTs; 1084 blastocysts; I2 = 82.2%, moderate quality evidence).

Twelve cohort studies (Kuwayama et al., 2005a,b; Stehlik et al., 2005; Liebermann and Tucker, 2006; Li et al., 2007; Rezazadeh Valojerdi et al., 2009; Wilding et al., 2010; Sifer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Van Landuyt et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Summers et al., 2016) with 64 982 cryopreserved pronuclear stage, cleavage-stage embryos or blastocysts were identified. The pooled data showed that vitrification was associated with a significant improvement in embryo cryosurvival (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07–1.18; P < 0.001; I2 = 98.6% very low quality evidence) (Supplementary Fig. S4). When stratified by embryo stage, the cryosurvival rates favored vitrification for both cleavage-stage embryos (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.07–1.22; P < 0.001; 10 cohort studies; 49 200 embryos; I2 = 99%; very low quality evidence) and blastocysts (RR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.02–1.15; P = 0.005; three cohort studies; I2 = 70.0%, very low quality evidence).

Discussion

The principal findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis support vitrification as being superior to slow-freezing for cryopreservation of both human oocytes and embryos in clinical ART. While the quality of the evidence for clinical outcomes comparing the two cryopreservation methods was mostly low and based on clinical pregnancy, rather than live-birth, that for post-thaw cryosurvival of oocytes and embryos was moderate.

The introduction of vitrification over the last decade and its extensive application has improved human oocyte and embryo cryosurvival rates and clinical outcomes after replacement of embryos cryopreserved at different stages of development. As shown in this study, recent evidence has revealed that this technique has closed the gap between fresh and cryopreserved oocytes in good-prognosis patients. However, although vitrification has allowed a substantial improvement in oocyte cryosurvival, when applied in an unselected population of patients (e.g. as a result of law) the clinical outcomes remained generally low (Fig. 2b). For embryo and blastocyst cryosurvival, available data suggest an improvement with the use of vitrification compared to slow-freezing, albeit over a wide range (30–93%). Accordingly, a typical laboratory could improve from ~60% embryo cryosurvival rate using slow-freezing to 78–100% embryo cryosurvival rate using vitrification. A beneficial treatment effect was also identified in RCTs for CPRs and LBRs per embryo and/or blastocyst warming cycle and per transfer.

Due to the improved cryosurvival outcomes with vitrification (Evans et al., 2014; Argyle et al., 2016) many laboratories worldwide have completely replaced slow-freezing with vitrification. It is therefore unlikely that additional prospective comparisons with current protocols will be performed.

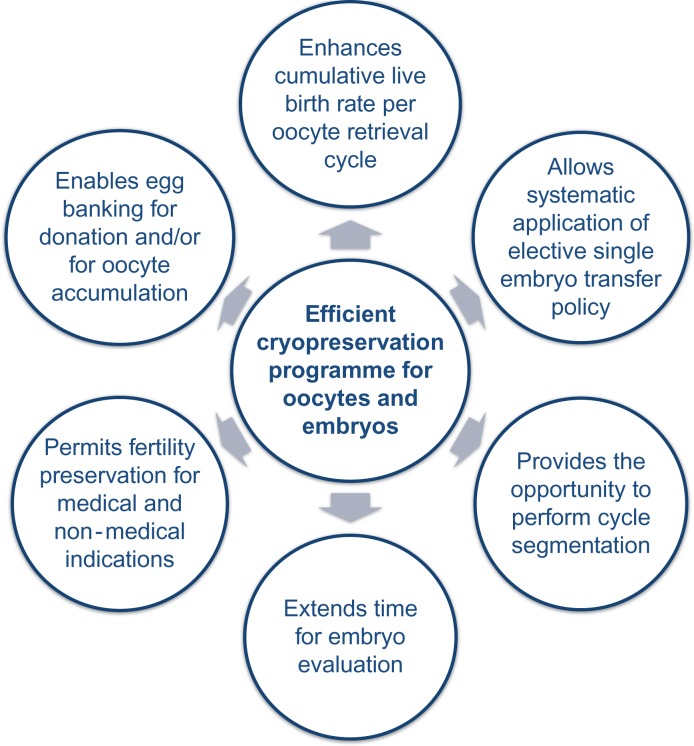

The optimized oocyte/embryo/blastocyst cryosurvival rates and clinical outcomes achieved with the use of vitrification have important clinical implications, which together allow a personalized approach in the care of different patient populations (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Clinical implications related to optimization of cryopreservation in IVF.

Contribution of cryopreservation to the cumulative LBR

Cryopreserved embryo transfers contribute substantially to the total success rate of an IVF cycle. Cumulative live birthrate (CLB) is defined as the likelihood of having an offspring after the utilization of all retrieved oocytes and associated embryos, thereby involving the transfer of fresh as well as all cryopreserved embryos. CLB is acknowledged as the most appropriate outcome measure in IVF to be used by practitioners and health administrators (Tiitinen et al., 2001). It has been estimated that in Europe in 2011 cryopreservation contributed to the overall LBR by 4% (LBR increasing from 19.7% with only fresh cycles to 24.0% including cryo-cycles) (Kupka et al., 2016). In countries where cryopreservation is systematically applied, the contribution is even more apparent: Finland +13.4%, Switzerland +10.2% and Australia and New Zealand +13.5% (Macaldowie et al., 2012; Kupka et al., 2016). These data reflect improvements obtained in embryo culture, cryopreservation technologies and/or the adoption of a more conservative embryo transfer policy (i.e. when fewer embryos are transferred in fresh cycles, more are available for cryopreservation).

Embryo transfer policy and cryopreservation

Considerable differences exist in embryo transfer policies across the world. Where not legally restricted, the number of embryos transferred simultaneously depends upon clinical decision-making, reimbursement strategies and other financial considerations and competency in cryopreservation technologies. Despite a general trend towards transferring fewer embryos (Clua et al., 2012), the mean percentage of single embryo transfers was only 27% in Europe in 2011 (Kupka et al., 2016) and 17% in the USA (CDC, 2011). On the other hand, in Australia and New Zealand, single embryo transfer is performed in more than 75% of cycles (Macaldowie et al., 2012). The incidence of multiple pregnancies, an unavoidable outcome of IVF when more than one embryo is transferred, is strongly correlated to the embryo transfer policy and varies from 19.8% in USA (CDC, 2011) and 19.2% in Europe (Kupka et al., 2016) to 6.5% in Australia and New Zealand (Macaldowie et al., 2012).

The main reasons for transferring more than one embryo are associated with the relative low efficiency of IVF, the poor prediction for embryo implantation potential and concerns regarding the quality of cryopreservation programmes. Other motivations are also related to the emotional and financial burden of ART treatment and lack of strong guidelines or regulatory bodies concerning embryo transfer policy (ESHRE Campus report 2001). In this context, it is clear that improvements in embryology technologies, including embryo assessment and cryopreservation protocols, are essential for promoting single embryo transfer policies with an aim to reduce the maternal and neonatal risks associated with multiple gestations. Of note, elective single embryo transfer policy combined with enhanced embryo selection and vitrification is also a realistic option in poor-prognosis patients of advanced maternal age (Ubaldi et al., 2015).

IVF cycle segmentation

A new strategy, called ‘cycle segmentation’, has recently been proposed that comprises a planned ‘freeze all’ of all oocytes and/or embryos. In this setting ovarian stimulation is optimized, including final oocyte maturation triggering with GnRH agonist in an antagonist cycle, all oocytes and/or embryos are cryopreserved (segment A) and later transferred to a receptive endometrium in a subsequent cycle (segment B) (Devroey et al., 2011). This approach has been tested with cryopreserved oocytes, pronuclear-stage and/or cleaved embryos in patients at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) (Griesinger et al., 2007,2011; Herrero et al., 2011). With this strategy, the risk of OHSS can be almost eliminated (Fatemi et al., 2010; Youssef et al., 2014).

Furthermore, transfer of exclusively cryopreserved single blastocysts in a population-based cohort study was found to decrease the risk of ectopic pregnancy (Li et al., 2015) and increase IVF success rates with no increase in adverse perinatal outcomes (Li et al., 2014). Improvements of clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates with the use of cryopreserved compared to fresh embryos have been reported in a recent meta-analysis (Roque et al., 2013). Additionally, similar efficacy was found in an RCT comparing outcomes following fresh transfer to that following freeze-all at either the blastocyst or the pronuclear-stage (Shapiro et al., 2015). Although cryopreservation cannot guarantee the survival of all embryos, these results clearly underscore the utility of cryopreservation in increasing the safety of IVF treatments, especially among high-responder patients, without affecting the cumulative pregnancy rate.

Cryopreservation and enhanced embryo evaluation

Embryo evaluation continues to be performed primarily by morphological assessment and/or morphokinetic analysis at different stages of development. However, static and dynamic morphological evaluations have limited clinical value (Guerif et al., 2007; Racowsky et al., 2009; Kaser and Racowsky 2014). Significant improvements in implantation rates in different patient populations have been obtained by the introduction of chromosomal aneuploidy testing at the blastocyst stage (Dahdouh et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015). This strategy combines different procedures including blastocyst culture, biopsy and cryopreservation. The improvements in cryosurvival rates achieved with vitrification of biopsied blastocysts (Escriba et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009) have provided an important contribution to the widespread implementation of this technology. Future challenges in embryology will deal with further enhancement of embryo evaluation beyond aneuploidy testing and to identify the patient populations best served by such testing. Several studies are currently ongoing that investigate correlations among ‘-omic’ profiling, metabolism, spent culture media analysis and embryo quality (reviewed in Gardner et al., 2015). These studies offer promise in the coming years to increase the predictive power for implantation. The availability of reliable vitrification protocols for cryopreservation allows an extension of time available for embryo evaluation by such indirect measures, thereby affording a potential for implementation of new validated approaches for embryo selection.

New possibilities related to oocyte cryopreservation

Oocyte cryopreservation is a relatively new technology in ART but has already important indications. One of the most common applications of oocyte cryopreservation is for oocyte donation programmes. The introduction of oocyte banks offers different advantages including reduced waiting time, no need for patient synchronization, improved safety to prevent disease transmission and the possibility to increase donor pools. The increased availability of vitrified donor eggs has, in turn, allowed the widespread application of oocyte donation and the implementation of new forms of collaboration between centres (even when located in different countries). For example, an egg bank may provide donor evaluation and screening, ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval and cryopreservation, and then release these cryopreserved donor oocytes for recipient use at associated IVF clinics (Nagy et al., 2015). Consequently, oocyte vitrification has provided important benefits for patients requiring donation, especially in those countries where there is a lack of donors.

Oocyte cryopreservation can be used as a new strategy to accumulate oocytes in poor-responder patients (Cobo et al., 2012). It is also a back-up procedure, which can be performed in case of failure to obtain a semen sample on the day of oocyte retrieval.

The developments in oocyte cryopreservation after the introduction of vitrification have also increased incentives to offer fertility preservation for patients receiving gonadotoxic therapies for cancer or other medical diseases (ASRM 2013; De Vos et al., 2014). The possibility of preserving oocytes is of considerable importance in this context. Oocyte cryopreservation, instead of the use of male-partner/donor sperm to create embryos, allows the possibility of reproductive autonomy in women without partners at the time when their fertility preservation is desired (Rienzi and Ubaldi, 2015). Finally, oocyte vitrification can also be used for elective fertility preservation for women who are conscious of the decline in oocyte quality and quantity with advancing maternal age but who are not ready to become pregnant (Stoop 2011).

Of note, when oocyte cryopreservation is imposed by law restrictions and applied to an unselected population of infertile patients the clinical outcomes are compromised.

Standardization of protocols and automation

Unlike slow-freezing, vitrification does not require a programmable freezing machine to provide specific cooling parameters. The technique is exclusively manual and is thus operator dependent. Furthermore, different commercial kits for vitrification are available and differ with respect to the solutions and devices utilized. Vitrification effectiveness may thus be highly variable and dependent on the protocols and experience of a laboratory. The heterogeneity of methods applied can create challenges with transportation of vitrified samples between laboratories using different cryoprotectant mixtures and/or vitrification devices. A rigorous process of standardization is therefore advocated. Comparative studies should be undertaken to establish best practices that would then be adopted universally (as occurred for slow-freezing 30 years ago). Indeed, attempts to promote standardization, consistency and efficiency are already underway with the introduction of automation (Roy et al., 2014). However, this approach requires considerable financial investment and its implementation is thus still limited.

Obstetric and perinatal outcomes

Although cryopreservation of oocytes and embryos is now a well-established procedure, long-term follow-up studies of children are still sparse. Data from systematic reviews and individual cohort studies are mostly reassuring, suggesting that pregnancies obtained from a cryopreserved oocyte and/or embryo transfer are not associated with increased perinatal risks compared with those resulting from fresh embryo transfer (Wang et al., 2005; Chian et al., 2009; Noyes et al., 2009; Wennerholm et al., 2009; Cobo et al., 2010; Pelkonen et al., 2010; Pinborg et al., 2010; Maheshwari et al., 2012; Levi-Setti et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Cobo et al., 2014; Belva et al., 2016; De Munch et al., 2016; Levi-Setti et al., 2016). Obstetric and perinatal complications (e.g. antepartum haemorrhage, preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birthweight and perinatal mortality) are even lower when frozen or vitrified embryos are replaced, likely as a consequence of the natural uterine environment that may better support early placentation and embryogenesis (Wennerholm et al., 2009; Maheshwari et al., 2012; Belva et al., 2016). Moreover, further reassuring evidence comes from studies evaluating the safety of oocyte vitrification in oocyte donation programmes (Chian et al., 2009; Noyes et al., 2009; Cobo et al., 2010; Cobo et al., 2014; De Munch et al., 2016) and in fertility preservation patients (Martinez et al., 2014).

Conclusions

Cryopreservation is an essential component in the treatment of patients undergoing ART and should be optimized in every IVF laboratory, as it allows for increased cumulative LBRs and offers the possibility to reduce multiple gestations and OHSS risk. According to the available evidence appraised in this systematic review and meta-analysis, vitrification is the best strategy for cryopreservation of all developmental stages from mature oocyte to embryos at the blastocyst stage. As this technique significantly increases oocyte and embryo cryosurvival rates when compared to slow-freezing, it has led to an improvement in clinical outcomes in cryopreserved cycles and also has made fertility preservation and donor oocyte banks a viable option for patients. Furthermore, it allows for reliable segmentation of the IVF cycle by temporally disconnecting the stimulation process from embryo transfer; consequently, this affords additional time for new invasive and non-invasive methods of embryo selection. Finally, if standardized and/or automated, the consistency and efficiency of the technique would likely be assured across all laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Ms Jessica Goldstein, RN, with the systematic search of the literature pertaining to oocyte cryopreservation and Mary D. Sammel, ScD, with data analysis.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at http://humupd.oxfordjournals.org/.

Authors’ roles

Conception and design (LR, CR, SV, CG); search strategy (RM, AL, DJK); data extraction, analysis (CG) and interpretation (all authors); drafting the manuscript (LR); critical revision of the manuscript (all authors).

Funding

This study was funded by the World Health Organization (WHO) to support the gathering of evidence in the context of the WHO Global Consultation for the development of global guidance: Addressing evidence-based guidance on infertility diagnosis, management and treatment.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- AbdelHafez FF, Desai N, Abou-Setta AM, Falcone T, Goldfarb J. et al. Slow-freezing, vitrification and ultra-rapid freezing of human embryos: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2010;20:209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhafez F, Xu J, Goldberg J, Desai N. Vitrification in open and closed carriers at different cell stages: assessment of embryo survival, development, dna integrity and stability during vapor phase storage for transport. BMC Biotechnol 2011;11:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almodin CG, Minguetti-Camara VC, Paixao CL, Pereira PC. Embryo development and gestation using fresh and vitrified oocytes. Hum Reprod 2010;25:1192–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori M, Licata E, Dani G, Cerusico F, Versaci C, Antinori S. Cryotop vitrification of human oocytes results in high survival rate and healthy deliveries. Reprod Biomed Online 2007;14:72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyle CE, Harper JC, Davies MC. Oocyte cryopreservation: where are we now. Hum Reprod Update 2016;22:440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban B, Urman B, Ata B, Isiklar A, Larman MG, Hamilton R, Gardner DK. A randomized controlled study of human Day 3 embryo cryopreservation by slow-freezing or vitrification: vitrification is associated with higher survival, metabolism and blastocyst formation. Hum Reprod 2008;23:1976–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belva F, Bonduelle M, Roelants M, Verheyen G, Van Landuyt L. Neonatal health including congenital malformation risk of 1072 children born after vitrified embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 2016;31:1610–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal D, Colturato LF, Leef DM, Kort HI, Nagy ZP. Evaluation of blastocyst recuperation, implantation and pregnancy rates after vitrification/warming or slow freezing/ thawing cycles. Fertil Steril 2008;90:277–278. [Google Scholar]

- Borini A, Lagalla C, Bonu MA, Bianchi V, Flamigni C, Coticchio G. Cumulative pregnancy rates resulting from the use of fresh and frozen oocytes: 7 years’ experience. Reprod Biomed Online 2006. a;12:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borini A, Sciajno R, Bianchi V, Sereni E, Flamigni C, Coticchio G. Cinical outcome of oocyte cryopreservation after slow-cooling with a protocol utilizing a high sucrose concentration. Hum Reprod 2006. b;21:512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borini A, Bianchi V, Bonu MA, Sciajno R, Sereni E, Cattoli M, Mazzone S, Trevisi MR, Iadarola I, Distratis V et al. Evidence-based clinical outcome of oocyte slow-cooling. Reprod Biomed Online 2007;15:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borini A, Levi Setti PE, Anserini P, De Luca R, De Santis L, Porcu E, La Sala GB, Ferraretti A, Bartolotti T, Coticchio G et al. Multicenter observational study on slow-cooling oocyte cryopreservation: clinical outcome. Fertil Steril 2010;94:1662–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YX, Xing Q, Li L, Cong L, Zhang ZG, Wei ZL, Zhou P. Comparison of survival and embryonic development in human oocytes cryopreserved by slow-freezing and vitrification. Fertil Steril 2009;92:1306–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC , Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Health. Assisted Reproductive Technology. National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/ART/ART2011.

- Chamayou S, Alecci C, Ragolia C, Storaci G, Maglia E, Russo E, Guglielmino A. Comparison of in-vitro outcomes from cryopreserved oocytes and sibling fresh oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online 2006;12:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chian RC, Huang JY, Gilber L, Son WY, Holzer H, Cui SJ, Buckett WM, Tulandi T, Tan SL. Obstetric outcomes following vitrification of in vitro and in vivo matured oocytes. Fertil Steril 2009;91:2391–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cil AP, Bang H, Oktay K. Age-specific probability of live birth with oocyte cryopreservation: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2013;100:492–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clua E, Tur R, Coroleu B, Boada M, Rodríguez I, Barri PN, Veiga A. Elective single-embryo transfer in oocyte donation programmes: should it be the rule. Reprod Biomed Online 2012;25:642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo A, Kuwayama M, Pérez S, Ruiz A, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Comparison of concomitant outcome achieved with fresh and cryopreserved donor oocytes vitrified by the Cryotop method. Fertil Steril 2008;89:1657–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo A, Meseguer M, Remohi J, Pellicer A. Use of cryo-banked oocytes in an ovum donation programme: a prospective, randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Hum Reprod 2010;25:2239–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo A, Remohí J, Chang CC, Nagy ZP. Oocyte cryopreservation for donor egg banking. Reprod Biomed Online 2011. a;23:341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo A, Diaz C. Clinical application of oocyte vitrification: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril 2011. b;96:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo A, Garrido N, Crespo J, José R, Pellicer A. Accumulation of oocytes: a new strategy for managing low-responder patients. Reprod Biomed Online 2012;24:424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo A, Serra V, Garrido N, Olmo L, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Obstetric and perinatal outcome of babies born from vitrified oocytes. Fertil Steril 2014;102:1006–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Simons RF, Edwards RG, Fehilly CB, Fishel SB. Pregnancies following the frozen storage of expanding human blastocysts. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf 1985;2:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetsier T, Dhont M. Avoiding multiple pregnancies in in-vitro fertilization: who's afraid of single embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 1998;13:2663–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrock S, Peeraer K, Fernandez Gallardo E, De Neubourg D, Spiessens C, D'Hooghe TM. Vitrification of cleavage stage day 3 embryos results in higher live birth rates than conventional slow-freezing: a RCT. Hum Reprod 2015;30:1820–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Munck N, Santos-Ribeiro S, Stoop D, Van de Velde H, Verheyen G. Open versus closed oocyte vitrification in an oocyte donation program: a prospective randomized sibling oocyte study. Hum Reprod 2016;31:337–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis L, Cino I, Rabellotti E, Papaleo E, Calzi F, Fusi FM, Brigante C, Ferrari A. Oocyte cryopreservation: clinical outcome of slow-cooling protocols differing in sucrose concentration. Reprod Biomed Online 2007;14:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos M, Smitz J, Woodruff TK. Fertility preservation in women with cancer. Lancet 2014;384:1302–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroey P, Polyzos NP, Blockeel C. An OHSS-Free Clinic by segmentation of IVF treatment. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2593–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JO, Richter KS, Lim J, Stillman RJ, Graham JR, Tucker MJ. Successful elective and medically indicated oocyte vitrification and warming for autologous in vitro fertilization, with predicted birth probabilities for fertility preservation according to number of cryopreserved oocytes and age at retrieval. Fertil Steril 2016;105:459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar DH, Gook DA. A critical appraisal of cryopreservation (slow cooling versus vitrification) of human oocytes and embryos. Hum Reprod Update 2012;18:536–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribá MJ, Zulategui JF, Galán A, Mercader A, Remohí J. de los Santos MJ. Vitrification of preimplantation genetically diagnosed human blastocysts and its contribution to the cumulative ongoing pregnancy rate per cycle by using a closed device. Fertil Steril 2008;89:840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethics Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine Fertility preservation and reproduction in patients facing gonadotoxic therapies: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2013;100:1224–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Hannan NJ, Edgell TA, Vollenhoven BJ, Lutjen PJ, Osianlis T, Salamonsen LA, Rombauts L. Fresh versus frozen embryo transfer: backing clinical decisions with scientific and clinical evidence. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:808–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri R, Porcu E, Marsella T, Rocchetta G, Venturoli S, Flamigni C. Human oocyte cryopreservation: new perspectives regarding oocyte survival. Hum Reprod 2001;16:411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini R, Brambillasca F, Renzini MM, Merola M, Comi R, De Ponti E, Dal Canto MB. Human oocyte cryopreservation: comparison between slow and ultrarapid methods. Reprod Biomed Online 2009;19:171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano G, Fontenelle N, Vannin AS, Biramane J, Devreker F, Englert Y, Delbaere A. A randomized controlled trial comparing two vitrification methods versus slow-freezing for cryopreservation of human cleavage stage embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet 2014;31:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahdouh EM, Balayla J, García-Velasco JA. Impact of blastocyst biopsy and comprehensive chromosome screening technology on preimplantation genetic screening: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Reprod Biomed Online 2015;30:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESHRE Campus Course Report Prevention of twin pregnancies after IVF/ICSI by single embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 2001;4:790–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi HM, Kyrou D, Bourgain C, Van den Abbeel E, Griesinger G, Devroey P. Cryopreserved-thawed human embryo transfer: spontaneous natural cycle is superior to human chorionic gonadotropin-induced natural cycle. Fertil Steril 2010;94:2054–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EJ, Li X, Ferry KM, Scott K, Treff NR, Scott RT Jr. Oocyte vitrification does not increase the risk of embryonic aneuploidy or diminish the implantation potential of blastocysts created after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a novel, paired randomized controlled trial using DNA fingerprinting. Fertil Steril 2012;3:644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Meseguer M, Rubio C, Treff NR. Diagnosis of human preimplantation embryo viability. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:727–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García JI, Noriega-Portella L, Noriega-Hoces L. Efficacy of oocyte vitrification combined with blastocyst stage transfer in an egg donation program. Hum Reprod 2011;26:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glujovsky D, Riestra B, Sueldo C, Fiszbajn G, Repping S, Nodar F, Papier S, Ciapponi A. Vitrification versus slow-freezing for women undergoing oocyte cryopreservation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesinger G, von Otte S, Schroer A, Ludwig AK, Diedrich K, Al-Hasani S, Schultze-Mosgau A. Elective cryopreservation of all pronuclear oocytes after GnRH agonist triggering of final oocyte maturation in patients at risk of developing OHSS: a prospective, observational proof-of-concept study. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1348–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesinger G, Schultz L, Bauer T et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome prevention by gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist triggering of final oocyte maturation in a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol in combination with a ‘freeze-all’ strategy: a prospective multicentric study. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2029–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifo JA, Noyes N. Delivery rate using cryopreserved oocytes is comparable to conventional in vitro fertilization using fresh oocytes: potential fertility preservation for female cancer patients. Fertil Steril 2010;93:391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerif F, Le Gouge A, Giraudeau B, Poindron J, Bidault R, Gasnier O, Royere D. Limited value of morphological assessment at days 1 and 2 to predict blastocyst development potential: a prospective study based on 4042 embryos. Hum Reprod 2007;2:1973–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng BC. Oocyte cryopreservation as alternative to embryo cryopreservation - some pertinent ethical concerns. Reprod Biomed Online 2007;14:402–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero L, Pareja S, Losada C, Cobo AC, Pellicer A, Garcia-Velasco JA. Avoiding the use of human chorionic gonadotropin combined with oocyte vitrification and GnRH agonist triggering versus coasting: a new strategy to avoid ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2011;95:1137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Lee TH, Chen SU et al. Successful pregnancy following blastocyst cryopreservation using super-cooling ultra-rapid vitrification. Hum Reprod 2005;20:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isachenko V, Montag M, Isachenko E, Dessole S, Nawroth F, van der Ven H. Aseptic vitrification of human germinal vesicle oocytes using dimethyl sulfoxide as a cryoprotectant. Fertil Steril 2006;85:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinkova L, Selman HA, Arav A, Strehler E, Reeka N, Sterzik K. Twin pregnancy after vitrification of 2-pronuclei human embryos. Fertil Steril 2002;77:412–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jericho H, Wilton L, Gook DA, Edgar DH. A modified cryopreservation method increases the survival of human biopsied cleavage stage embryos. Hum Reprod 2003;18:568–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Mazur P. High survival of mouse oocytes/embryos after vitrification without permeating cryoprotectants followed by ultra-rapid warming with an IR laser pulse. Sci Rep 2015;5:927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser DJ, Racowsky C. Clinical outcomes following selection of human preimplantation embryos with time-lapse monitoring: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen N, Kananen K, Huhtala H, Keränen S, Tinkanen H. The freezing method of cleavage stage embryos has no impact on the weight of the newborns. J Assist Reprod Genet 2016;33:393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee S, Lee J et al. Study on the vitrification of human blastocysts. II: Effect of vitrification on the implantation and the pregnancy of human blastocysts. Korean J Fertil Steril 2000;27:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kolibianakis EM, Venetis CA, Tarlatzis BC. Cryopreservation of human embryos by vitrification or slow-freezing: which one is better. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2009;21:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshova L, Gianaroli L, Magli C, Ferraretti A, Trounson A. Birth following vitrification of a small number of human oocytes: case report. Hum Reprod 1999;14:3077–3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshova LL, Shaw JM. A strategy for rapid cooling of mouse embryos within a double straw to eliminate the risk of contamination during storage in liquid nitrogen. Hum Reprod 2000;15:2604–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupka MS, D'Hooghe T, Ferraretti AP, de Mouzon J, Erb K, Castilla JA, Calhaz-Jorge C, De Geyter CH, Goossens V. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2011: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2016;31:233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama M, Vajta G, Kato O, Leibo SP. Highly efficient vitrification method for cryopreservation of human oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online 2005. a;11:300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama M, Vajta G, Ieda S et al. Comparison of open and closed methods for vitrification of human embryos and the elimination of potential contamination. Reprod Biomed Online 2005. b;11:608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Sala GB, Nicoli A, Villani MT, Pescarini M, Gallinelli A, Blickstein I. Outcome of 518 salvage oocyte-cryopreservation cycles performed as a routine procedure in an in vitro fertilization program. Fertil Steril 2006;86:1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle B, Testart J, Renard JP. Human embryo features that influence the success of cryopreservation with the use of 1,2 propanediol. Fertil Steril 1985;44:645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Illingworth P, Wilton L, Chambers GM. The clinical effectiveness of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidy in all 24 chromosomes (PGD-A): systematic review. Hum Reprod 2015;30:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibo SP, Songsasen N. Cryopreservation of gametes and embryos of non-domestic species. Theriogenology 2002;57:303–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi Setti PE, Albani E, Novara PV, Cesana A, Morreale G. Cryopreservation of supernumerary oocytes in IVF/ICSI cycles. Hum Reprod 2006;21:370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi Setti PE, Albani E, Morenghi E, Morreale G, Delle Piane L, Scaravelli G, Patrizio P. Comparative analysis of fetal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancies from fresh and cryopreserved/thawed oocytes in the same group of patients. Fertil Steril 2013;100:396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi Setti PE, Porcu E, Patrizio P, Vigiliano V, de Luca R, d'Aloja P, Spoletini R, Scaravelli G. Human oocyte cryopreservation with slow-freezing versus vitrification. Results from the National Italian Registry Data, 2007-2011. Fertil Steril 2014;102:90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Setti PE, Borini A, Patrizio P, Bolli S, Vigiliano V, De Luca R, Scaravelli G. ART results with frozen oocytes: data from the Italian ART registry (2005-2013). J Assist Reprod Genet 2016;33:123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]