Abstract

This article communicates our study to elucidate the molecular determinants of weak Mg2+ interaction with the ribonuclease H (RNH) domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in solution. Since the interaction is weak (a ligand-dissociation constant > 1 mM), non-specific Mg2+ interaction with the protein or interaction of the protein with other solutes that are present in the buffer solution can confound the observed Mg2+-titration data. To investigate these indirect effects, we monitored changes in the chemical shifts of backbone amides of RNH by recording NMR 1H-15N single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra upon titration of Mg2+ into an RNH solution. We performed the titration in three different conditions: (1) in the absence of NaCl, (2) in the presence of 50 mM NaCl, and (3) at a constant 160 mM Cl− concentration. Careful analysis of these three sets of titration data, along with molecular dynamics simulation data of RNH with Na+ and Cl− ions, demonstrates two characteristic phenomena distinct from the specific Mg2+ interaction with the active site: (a) weak interaction of Mg2+, as a salt, with the substrate-handle region of the protein, (b) overall apparent lower Mg2+-affinity in the absence of NaCl compared to that in the presence of 50 mM NaCl. A possible explanation may be that the titrated MgCl2 is consumed as a salt and interacts with RNH in the absence of NaCl. In addition, our data suggest that Na+ increases the kinetic rate of the specific Mg2+ interaction at the active site of RNH. Taken together, our study provides biophysical insight into the mechanism of weak metal interaction on a protein.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Weak, transient molecular interactions are critically important in many biological processes, where they regulate low frequency events in cellular signaling as well as enzyme dynamics. For example, carbohydrates often weakly interact with proteins 1–3, the binding affinities of metals to protein, some of which are very weak, vary in individual systems 4–6, and weak ion interactions with a protein’s surface provide protein stability 7–9. Precise analysis of protein-protein interactions, as well as protein-ligand interactions, is crucial for understanding such physiologically relevant mechanisms and is also important in drug discovery 10–14.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is an extremely sensitive method to gain insight into structural, dynamical, and chemical changes of individual sites in macromolecules and is often used to characterize ligand-protein interactions by monitoring either protein or ligand signals 15–24. In particular, ligand-titration experiments in which protein signals are monitored, mostly by recording 1H-15N single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra or 1H-13C multi-quantum coherence (HMQC) spectra, are useful to identify both the affinity of ligands and their binding sites on proteins 15. When a ligand-protein interaction is weak, migration of protein chemical shifts as a function of ligand concentration is detected in the NMR spectra and exhibits a fast exchange régime. Analysis is typically straightforward using established approaches 15, 25–28.

However, when the ligand-protein interaction is extremely weak, with a ligand-dissociation constant > 1 mM, the analysis of ligand titration data is not straightforward because confounding effects, such as non-specific interaction of the ligand or interaction from other solutes in the solution, may complicate the analysis. Indeed, it is well known that solute composition influences NMR relaxation data recorded for proteins in aqueous solution 29–31. Although a method to investigate weak Mg2+ interactions, using a chelator diphosphate, has been described 32, this method does not provide information for the ligand binding site. Moreover, the method cannot be used with nucleotide binding proteins that may interact with the diphosphate. Thus, we propose a protocol that involves inspection of the entire dataset obtained from NMR fast-exchange titration to identify effects other than those from specific ligand-protein interactions. In addition, we also propose that data be acquired at different salt concentrations to allow better interpretation of the data.

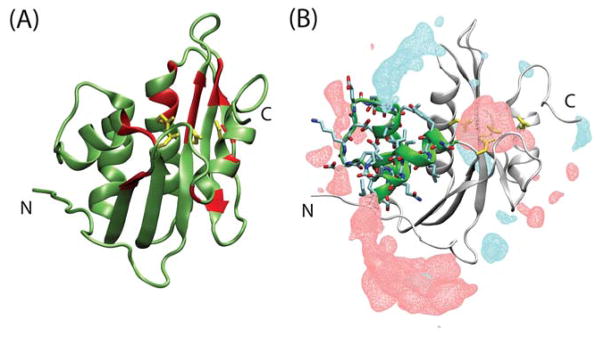

Here, we revisit the Mg2+ interaction with the ribonuclease H (RNH) domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) (Figure 1A), which was studied by us and other groups previously 33–37. The RNH domain is located at the C-terminus of RT and degrades the viral RNA from the RNA/DNA hybrid that forms during reverse transcription, an essential step in replication of the retrovirus 38, 39. RNH requires Mg2+ ion(s) for its activity and forms the metal binding site with four acidic groups, D443, E478, D498, and D549 (Figure 1A) 40–45. A two-metal interaction model is generally accepted in the respect of structure of RT, since in RT, binding affinity of a second divalent ion is increased in the quaternary complex, with a substrate, in physiological conditions 46–50. In contrast, in the absence of substrate in solution, only one Mg2+ ion is weakly coordinated at the RNH active site in RT, at KD, ~ 0.1 mM 36. Further, while Mg2+ ion interaction with the isolated RNH domain in solution is qualitatively explained with a single Mg2+-binding model (KD, ~ 10 mM), the previous titration data itself is better expressed with a two-Mg2+ interaction model (KD, ~ 3 mM and 35 mM) 34, 35. As a next step of the studies, we endeavored to answer a biophysical question about whether Mg2+ ions non-specifically interact with RNH in solution and how such non-specific interaction affects titration data.

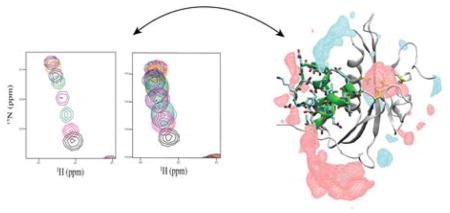

Figure 1.

Ribbon representations of the structure of the RNH domain and the metal binding site (yellow side chains), (A) alone and (B) with isosurface overlay showing ion densities of Na+ (red) and Cl− (blue) calculated using MD trajectories. In (A), red highlights 20 selected residues, for which chemical shift changes at all the Mg2+ concentrations were detected without signal overlap and those at 80 mM Mg2+ were one-standard deviation larger than the average values among all the residues (described in the Results). In (B), residues at the RNH substrate-handle region (residues 503 to 527, 42) are highlighted as green ribbons with stick representation of the side chains. The isosurfaces are at an isovalue of 1.7 × 10−4 (Å−3), corresponding to a salt concentration of approximately 282 mM (described in the Results). In panel B, there is a region of increased Na+ density near the substrate handle region. Note the bottom region includes Cl− density surrounded by Na+ density. The structure was drawn using PDB 3K2P.

To investigate the molecular determinants of Mg2+ interaction with the isolated RNH domain, we monitored changes in the chemical shifts of RNH backbone amides by recording NMR 1H-15N single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra upon Mg2+ titration in three different conditions: (1) in the absence of NaCl, (2) in the presence of 50 mM NaCl, and (3) at a constant 160 mM Cl− concentration, the latter achieved by a two-fold reduction in Na+ concentration when Mg2+ was titrated. Our study demonstrated two effects of Mg2+, in addition to its interaction with the active site: (a) weak interaction of Mg2+, as a salt, with the substrate-handle region that is located adjacent to the active-site residues, and (b) an influence of NaCl on the effective Mg2+ concentration. We think that the latter observation may be due to the consumption of Mg2+ as a salt by the substrate-handle region and perhaps by other regions in a non-specific manner. Consistent with our NMR observations, MD simulation data indicate weak localization of cations on the substrate handle region and the active site. Our study elucidates non-specific interactions of Mg2+ ions and provides biophysical insight into the determinants of weak metal-protein interactions.

Experimental and Theoretical Methods

Protein Preparation

The wild type RNH used for this experiment is the same construct used previously and was expressed and purified as reported 51. In brief, cDNA encoding residues 427–560 of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase was expressed by inserting it into pE-SUMO vector (LifeSensors, Malvern, PA) with a six histidine tag (His6-) at the N-terminus of the SUMO-fusion construct. The protein was expressed in E. Coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells using IPTG for induction. Soluble RNH was extracted from the cell lysate and purified using HisTrap HP columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and gel filtration on a Superdex75 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After removal of the N-terminal His6-SUMO fusion by digestion with ULP1 enzyme, the RNH was separated from His-tagged proteins using a HisTrap column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Purified RNH was stored at −80 °C with a buffer containing 25 mM Sodium Phosphate, 100 mM NaCl and 0.02% NaN3, at pH 7.0. The buffers for NMR experiments were exchanged as described below.

NMR samples

A total of 27 NMR samples were prepared to conduct three different Mg2+ titration experiments: (I) MgCl2 titration in a 20 mM bisTris buffer (pH 7.2) in the absence of additional NaCl, referred to as MgCl2(0NaCl), (II) MgCl2 titration in a 20 mM bisTris buffer in the presence of 50 mM NaCl, MgCl2(50NaCl), (III) Mg2+ titration in a 20 mM bisTris buffer at constant Cl− concentration (160 mM), referred as MgCl2(const. Cl−). In each titration experiment, nine samples were made to vary Mg2+ concentrations at 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 70, and 80 mM. We prepared these samples in the following way.

First, RNH protein, ca. 3 mL at 180 μM, sufficient for the entire titration experiment, was dialyzed in a 20 mM bisTris buffer at pH 7.2 and diluted with D2O to reach 7.5% D2O concentration. Second, stock solutions of 240 mM MgCl2 (99.9% trace metals, Sigma-Aldrich), 5 M NaCl, and 480 mM NaCl (99.5 % Bioxtra, Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared using the same bisTris buffer as that used for protein. Last, each NMR sample for a 3 mm NMR tube, total volume of 150 μL, was prepared by mixing 100 μL of the protein solution with 50 μL of bisTris buffer containing NaCl and/or MgCl2, as described below. A 5 M NaCl stock solution was used to prepare (II) MgCl2(50NaCl) titration samples, while a 480 mM NaCl stock solution was used to prepare (III) MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration samples. A 240 mM MgCl2 stock solution was used in all three titrations. In (III), constant Cl− was achieved by decreasing the amount of NaCl when increasing MgCl2, maintaining the Cl− concentration at 160 mM. The final protein concentration for each NMR sample was 114 μM, containing 5% D2O. Details are described in Tables S1–S3.

NMR experiments and titration data analysis

The magnesium titrations into RNH were monitored by recording 1H-15N HSQC data at 20°C on a Bruker Avance 900 MHz spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA, USA). NMR spectra were processed and analyzed using NMRPipe 21 and CcpNmr 52. Note, three samples among the total 27 MgCl2 titration samples do not contain Mg2+ and have different NaCl concentrations. NMR spectra acquired for these Mg2+-free samples make a set of NaCl titration data: 0, 50 mM, and 160 mM NaCl concentration.

Chemical shift perturbation, Δδi, for each step i of the titration series was calculated as normalized chemical shift differences of 1H and 15N.

| (1) |

where γN and γH are gyromagnetic ratios of nitrogen and proton, respectively. Since relative changes are analyzed, the spectra were referenced through internal deuterium lock 53.

| (2) |

Uncertainty, , of Δδiobs was estimated using Eq. (2) for each titration point. Chemical shift errors for proton and nitrogen, and , were estimated from the peak position uncertainty at Nmrpipe. Using a 1:1 interaction model with a KD of a ligand, Δδi is calculated in Eq. (3).

| (3) |

Here, [L]i and [P]total stand for total ligand at titration point i, and protein concentration is uniform throughout the titration. The two unknown parameters, namely KD and the magnitude of chemical shift change at saturation, Δδ∞ = Δδbound – Δδfree, were optimized by minimizing the difference between the experimentally measured Δδobs and the Δδcal for each titration curve, as described previously 33. In this step, uniform shift uncertainty, by taking the average of δiuncert for each titration curve, was used.

Calculation of ion density from an MD simulation trajectory

Previously, a 200 ns MD simulation of the isolated RNH was performed 51. In this simulation, each structure was surrounded with TIP3 water in a rhombic dodecahedral box, allowing a 12 Å margin on all sides of the protein with a total of 21 Na+ and 18 Cl− ions, equivalent to ca. 100 mM salt concentration at neutral pH. The simulation did not include any Mg2+ ions. Based on the MD trajectories, we calculated the density of Na+ and Cl− ions in the following manner. Previously recorded frames, every 1 ps, were first aligned by backbone RMSD against the saved minimized starting structure. Then, the ions in each frame were re-centered, placing each ion at the periodic image closest to the protein. The number density (i.e. concentration, not charge density) was calculated using the volmap command in VMD 54, on a grid of 0.5 Å resolution. Each ion was represented by a normalized Gaussian distribution with a width equal to its van der Waals radius, and the resulting scalar fields were averaged over all of the frames in the trajectory. The resulting scalar field was portrayed as an isosurface using VMD software.

Results and discussion

Overview of Mg2+ titration to RNH by monitoring 1H-15N HSQC spectra

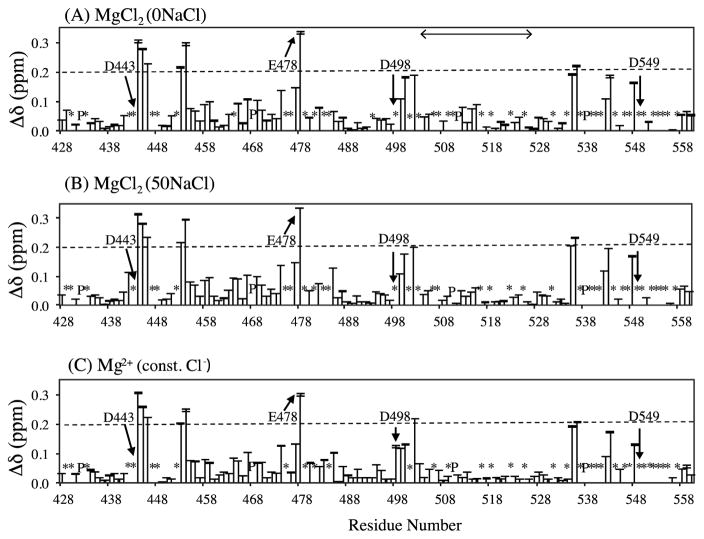

We titrated MgCl2 in three different conditions: MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), and MgCl2(const. Cl−). In all three Mg2+ titration experiments, the recorded spectra change as a function of Mg2+ concentration. Δδ values were calculated for 87 detectable backbone amide 1H-15N cross peaks using Eq. (1). The average uncertainty of Δδ, calculated using the propagation of error formula for 1H and 15N chemical shifts, was 0.00094 ± 0.00090 ppm in MgCl2(0NaCl), 0.00042 ± 0.00050 ppm in MgCl2(0NaCl), and 0.00092 ± 0.00097 ppm in MgCl2(0NaCl). Although pipetting error and sample instability may be larger than these noise uncertainties, such additional error was estimated to be at a level similar to the noise error obtained by examining the fluctuation of the smallest Δδ changes of the data (Figure S1). As expected, overall profiles of the chemical shift perturbations, obtained by comparing the Δδ values at 80 mM MgCl2, were very similar to one another among the three titration datasets (Figure 2). Several residues, particularly those close to the active site of RNH (i.e. residues D443, E478, D498, D549), exhibited large Δδ, over 0.2 ppm (approximately two-standard deviation above the average shift change) at 80 mM Mg2+ concentration. Significant changes in Δδ, over one-standard deviation above the average shift change, were observed in the regions surrounding the active site (Figure 1A). Similar chemical shift changes at and around the active site residues upon Mg2+ interaction were reported previously 33–35.

Figure 2.

Chemical shift perturbation, Δδ (ppm), at 80 mM Mg2+ concentration detected in (a) MgCl2(0NaCl), (b) MgCl2(50NaCl), and (c) Mg2+(const. Cl−) titration experiments. Error bars represent the uncertainty of Δδ. Asterisks (*) indicate unassigned or overlapped backbone NH amides, and P indicates prolines. Active site residues (D443, E478, D498, and D549) of RNH are labeled and indicated by arrows. Approximately two-standard deviations above the average shift change (~0.2 ppm) is shown by dashed line. A horizontal arrow in the top panel indicates the location of the substrate handle-region (residues 503–527).

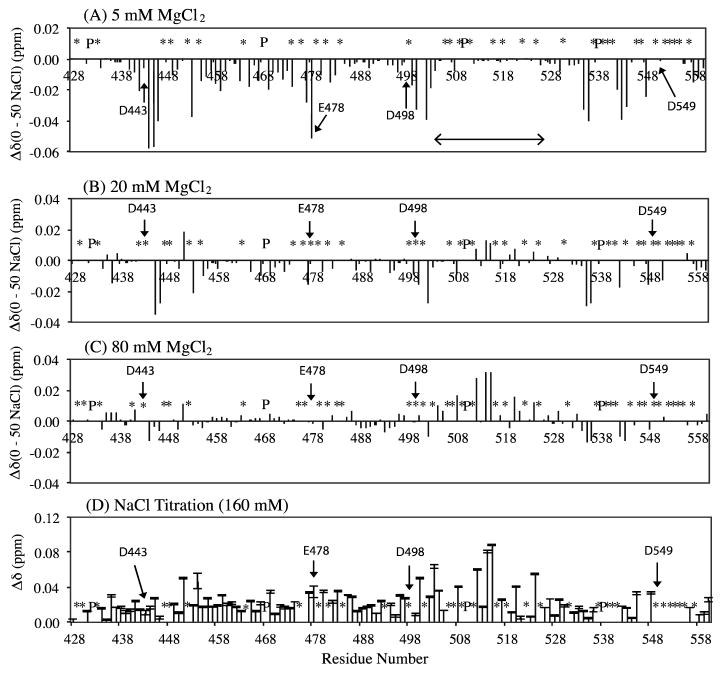

Even though the relative Δδ profiles, as a function of amino-acid residue number, for all three titrations are similar to one another (Figure 2), there were slight differences in Δδ values among the three data sets. In particular, two notable differences were observed upon comparison of Δδ magnitudes between MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl) (Figure 3A–3C). First, at a low, ~5 mM, MgCl2 concentration, Δδ values in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration were, in general, smaller than those in the MgCl2(50NaCl) titration, except for those of residues in the RNH substrate-handle region (residues 503 to 527), 42 (Figure 3A). Second, at high, 80 mM, MgCl2 concentration, Δδ values of the residues in the substrate-handle region were greater in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration than the MgCl2(50NaCl) titration (Figure 3C). We further analyzed these observations as described below.

Figure 3.

Differences in chemical shifts between MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl), labeled as Δδ(0 – 50 NaCl), at 5 mM (A), 20 mM (B), and 80 mM (C) MgCl2, and (D) chemical shift perturbation, Δδ(ppm), at 160 mM NaCl concentration detected using the 0 MgCl concentration points of MgCl2(0NaCl) and Mg2+(const. Cl−). A horizontal arrow in the top panel indicates the location of the substrate handle-region (residues 503–527). Asterisks (*) indicate unassigned or overlapped backbone NH amides, and P indicates prolines.

Salt interaction at the substrate handle region

Since the Mg2+ titration experiments were recorded at different NaCl concentrations, the combined first data points of each series (that is, at 0 mM MgCl2) generate a NaCl titration series at 0, 50 mM and 160 mM. Using these data, the effect of NaCl on RNH was qualitatively characterized by comparing the three spectra. As expected, the average chemical shift change for each residue upon 160 mM NaCl titration was small, less than 0.02 ppm (Figure 3D). Such a small NaCl effect, although 20 times larger than the chemical shift uncertainty, may be ignored in practical applications. However, in the substrate-handle region, the observed NaCl effect was significant, Δδ > 0.05 ppm, at comparable points in the Mg2+ titration series (Figure 3D). Interestingly, the pattern of Δδ at 160 mM NaCl, Figure 3D, is very similar to Δδ(0NaCl)-Δδ(50NaCl) at 80 mM MgCl2 concentration (Figure 3C). Thus, this comparison of the chemical shift changes indicates that the difference in the Δδ changes observed between MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl) in the substrate-handle region is mainly due to a NaCl effect.

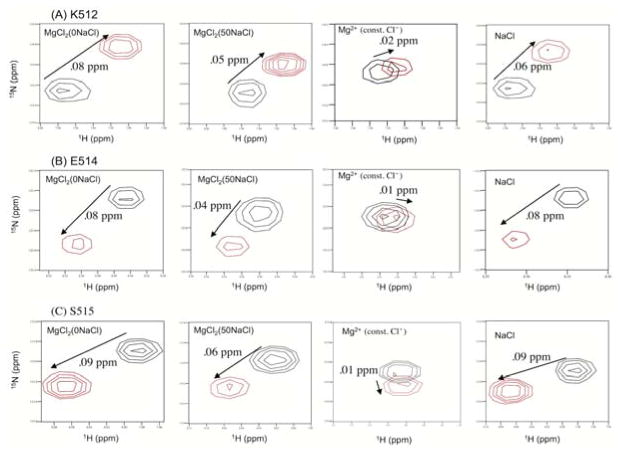

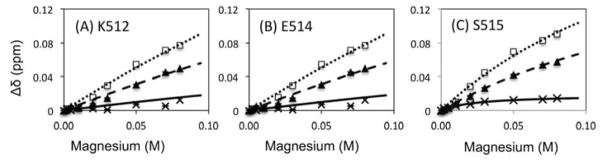

The salt effect observed in the substrate-handle region was further confirmed by comparing the chemical shift trajectories of MgCl2(0NaCl) with those of MgCl2(const. Cl−) in more detail (Figure 2). For residues K512, E514, and S515, located in the substrate-handle region, the directions of chemical shift changes upon MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl) titration differ from those of the MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration but are similar to those of the NaCl titration (Figure 4). These residues also exhibit larger chemical shift changes in the MgCl2(0NaCl) compared to the MgCl2(50NaCl) (Figure 4). Consistent with these observations, titration curves, i.e., plots of Δδ value as a function of MgCl2 concentration, were far from saturation even at 80 mM MgCl2 for the residues in the substrate-handle region (Figure 5, dash and dot lines). In contrast, build-up of the titration curves of the MgCl2(const. Cl−) are much weaker than those of MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl) (Figure 5, solid lines).

Figure 4.

Changes in chemical shifts in 1H-15N HSQC spectra upon Mg2+ titration and NaCl titration for RNH residues at the substrate-handle region, (A) K512, (B) E514, and (C) S515. Four panels are shown for each residue: from left to right, MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), Mg2+(const. Cl−), and NaCl. Spectra at 0 (black) and 80 mM (red) MgCl2 concentrations were compared in the MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), Mg2+(const. Cl−) titration data. Spectra at 0 (black) and 160 mM (red) NaCl concentrations were compared in the NaCl titration data.

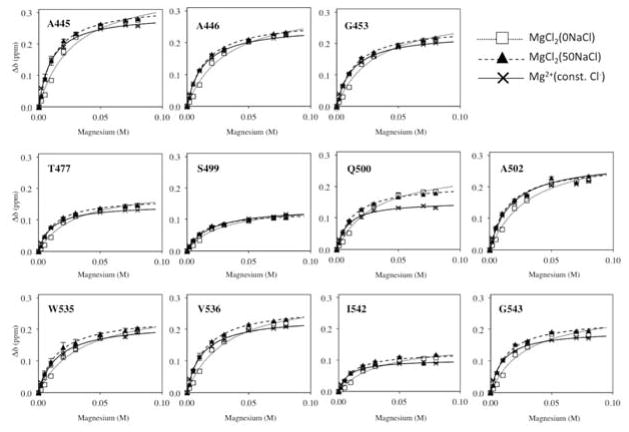

Figure 5.

Plots of Δδ as a function of Mg2+ concentration for residues (A) K512, (B) E514, and (C) S515 at the substrate-handle region of RNH. Experimental data points for MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), and Mg2+(const. Cl−) are represented by open square, closed triangle and cross symbols, respectively. Fit curves calculated assuming 1:1 interaction are shown by dotted, dashed, and solid lines for MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), and Mg2+(const. Cl−), respectively.

The substrate-handle region is known to be mobile in the isolated RNH domain 55, 56, and this region interfaces with the p51 domain in the p66 subunit in RT 57, 58. The region also contains five negatively charged and two positively charged residues. Unlike E. Coli RNH 59, there are no Trp residues in this region. Indeed, in our calculation of ion density using MD simulation trajectory, the charge distribution exhibits physically expected behavior, showing that Na+ is slightly localized at the substrate handle region (Figure 1B). For reference, this isovalue corresponds to a local salt concentration of 282 mM. The localization of solutes on a protein surface is a generally known phenomenon 7–9. Considering these structural characteristics of the substrate-handle region of HIV-1 RNH along with the solvent charge distribution calculated from the MD simulation trajectory, it is not surprising that this region experiences significant salt effect as observed in the NaCl titration data.

Weak salt effect to the entire protein

In contrast to the specific salt effect observed in the substrate-handle region, the remainder of residues in the protein exhibited an apparent weak Mg2+ interaction profile in MgCl2(0NaCl), compared to the MgCl2(50NaCl) condition (Figure 3A and 3B). This is not a one-point titration anomaly because the entire titration curve for each residue shows lower affinity binding in the MgCl2(0NaCl) condition, compared to the MgCl2(50NaCl) condition even for residues that exhibited Δδ values greater than two standard deviation above the average and did not overlap with other peaks throughout the titration: A445, A446, G453, T477, S499, Q500, A502, W535, V536, I542, G543 (Figure 6). This observation is not likely due to systematic error of the titrated amount of MgCl2 for three reasons. As described in the Experimental and Theoretical Methods, we used the same stock solution to prepare samples in parallel for the MgCl2(0NaCl) and the MgCl2(50NaCl) titrations but saw consistent lower affinity curves (Figure S2). Second, the Δδ values in the substrate-handle region show the opposite tendency and, thus, are not likely due to systematic depletion of the titration curves (Figure 3C). Last, we repeated the Mg2+ titration experiments, using a few NMR samples, and reproduced the low-affinity Mg2+ titration effect in the MgCl2(0NaCl) condition compared to the MgCl2(50NaCl) condition (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Plots of Δδ as a function of Mg2+ concentration for residues that exhibited Δδ values greater than two standard deviations above the average. The symbols used for the titration data points are the same as those in Figure 5.

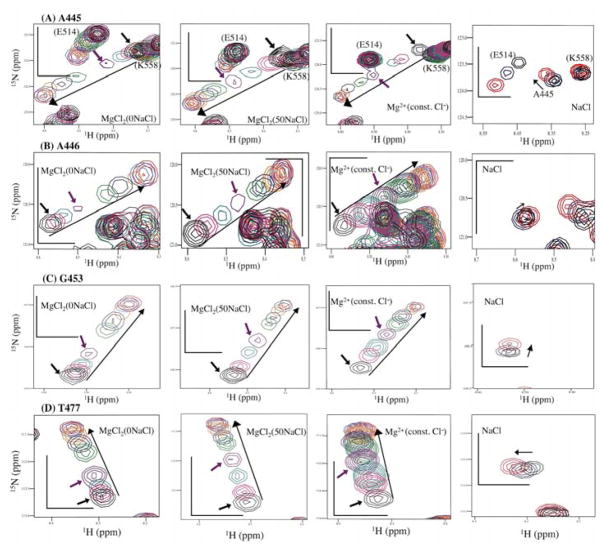

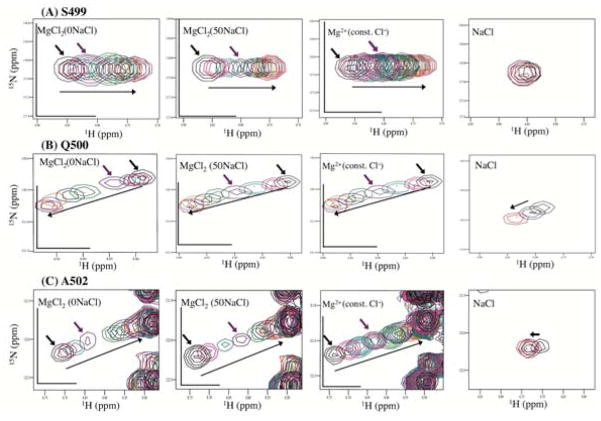

To further verify this apparent low-affinity MgCl2 response in the absence of NaCl, we inspected the individual trajectories of the NMR signals in the MgCl2(0NaCl) and the MgCl2(50NaCl) titration data sets, especially, for residues that exhibited significant Δδs and that did not overlap with other peaks throughout the titration (see Figure 6); among these, A445, A446, G453, and T477 are located in the RNH β-sheet region, S499, Q500, and A502 are close to the substrate-handle region, and V536, I542, and G543 are at the C-terminal α-helix (Figure 7, 8, 9, respectively). W535 was not included in the trajectory inspection because side chain motion, in addition to the Mg2+ interaction, may affect the trajectory (due to ring-current shift). At low Mg2+ concentration, as indicated by red and black arrows, the apparent low-affinity titration response in the MgCl2(0NaCl) condition, compared to MgCl2(50NaCl) and MgCl2(const. Cl−) conditions, was evident for most of the residues. However, in contrast to the observed salt effect for residues in the substrate-handle region (Figure 4), the orientations of the trajectories for each residue in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration were not necessarily the same as those in the NaCl titration (Figure 7, right). Therefore, the apparent low-affinity Mg2+ build-up for these residues (Figure 6) was not due to a weak salt effect but instead caused by a specific Mg2+ interaction. The apparent low-affinity build-up was not due to the pH shift caused by the different salt concentrations either (discussed in the section of the Mg2+ dissociation constant). Since the apparent low-affinity build-up is significant, particularly at low Mg2+ concentration, some of the titrated MgCl2 may interact with sites other than the active site, such as the substrate-handle region, and, thus, decrease the free Mg2+ concentration: as a result, the apparent build-up curve in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration might become weaker, compared to the calculated molar concentration of MgCl2 in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration.

Figure 7.

Changes in chemical shifts in 1H-15N HSQC spectra upon Mg2+ titration and NaCl titration for RNH residues in the β-sheet region, (A) A445, (B) A446, (C) G453, and (D) T477. Four panels are shown for each residue: from left to right, MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), Mg2+(const. Cl−), and NaCl. Overlay of 1H-15N HSQC signals were made for MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), and Mg2+(const. Cl−) titrations at 0 mM (black), 2 mM (pink), 5 mM (teal), 10 mM (purple), 20 mM (green), 30 mM (navy), 50 mM (orange), 70 mM (skyblue), and 80 mM (red) Mg2+ concentrations. Overlays of 1H-15N HSQC signals were made for NaCl titration at 0 (black), 50 mM (blue), and 160 mM (red). Arrows show the direction of chemical shift perturbation. Scales on each plot (black bars) represent 1 ppm for 15N and 0.1 ppm for 1H dimension.

Figure 8.

Changes in chemical shifts in 1H-15N HSQC spectra upon Mg2+ titration and NaCl titration for RNH residues close to the substrate-handle region, (A) S499, (B) Q500, and (C) A502. The same color coordination as in Figure 7 was used.

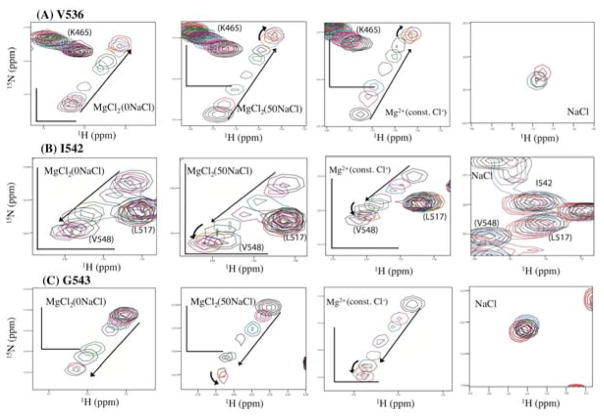

Figure 9.

Changes in chemical shifts in 1H-15N HSQC spectra upon Mg2+ titration and NaCl titration for RNH residues (A) V536, (B) I542, and (C) G543, in the last α-helix in RNH. The same color coordination as in Figure 7 was used. Trajectories of chemical shifts above 50 mM Mg2+ concentrations in the MgCl2(50NaCl) and the MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration spectra are outlined with curved arrows

Salt effects on the exchange rate of the Mg2+ interaction

When the on-rate of a ligand is within the molecular diffusion limit 60 (typically, 108 – 1010 s−1/M) and KD is ~1 mM, the off-rate is 105 – 108 s−1, which is most likely much faster than the difference in the chemical shifts between the free and the ligand-bound form, Δδ∞, at 900 MHz resonance frequency. In such a condition (i.e., in the fast exchange régime), NMR signals are typically sharp throughout the titration without exchange signal-broadening. However, even though Mg2+ is a very weak binder to RNH, the titration spectra in both MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl) titration experiments exhibited severe signal broadenings, observed as low signal intensity, at the mid-range, 20 – 60 mM, titration data points (Figure 7 and 8), indicating that the off-rate is not sufficiently large and is compatible to Δδ∞ 26. In contrast, the MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration did not produce such broadening for most residues (Figure 7 and 8). Titration data obtained in the MgCl2(const. Cl−) condition, containing 160 mM Cl−, also showed a saturation pattern and reached a plateau at > 50 mM Mg2+ concentration (Figure 6). These data suggest that an abundance of cations, not limited to Mg2+, affect the exchange rate of the Mg2+ interaction at the active site of RNH. In the ion density calculations, the highest Na+ density was observed at the active site (a primary metal binding) region (Figure 1B). Although the Na+ effect does not shift KD (described below), it may affect the on/off rate of the Mg2+ interaction.

Possible effects of conformational change on the second Mg2+ interaction

Residues V536, I542, and G543 are located in the last α-helix in RNH (helix E), and are known to undergo internal motion 55, 56, 61. The helix contains one of the active site residues, D549, and was previously suggested to be stabilized upon Mg2+ interaction 61. Consistent with previous observations, in all three titrations, MgCl2(0NaCl), MgCl2(50NaCl), and MgCl2(const. Cl−), these residues showed broadening of signals and were difficult to track (Figure 9) compared to other residues shown above (Figure 7 and 8). These residues, located in the last α-helix, exhibited significant non-linear chemical shift changes above 50 mM Mg2+ concentration in the MgCl2(50NaCl) and the MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration spectra (Figure 9, curved arrows), and, in a less pronounced manner, in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration spectra. Directions of the changes of chemical shifts at high Mg2+ concentration (> 50 mM) were quite different from those at low Mg2+ concentration (< 50 mM), suggesting that the second event happens only at high Mg2+ concentration. This observation is consistent with previous NMR titration data 35. Although titration profiles for the active-site residues should be analyzed to clarify whether the observed rate event is due to binding of the second Mg2+, sufficient data was not obtained due to severe signal broadening for the active-site residues. Only two of the active-site residues, E478 and D498, exhibited partial titration profiles (Figure S3).

T477 and Q500 also exhibited significant Δδ upon Mg2+ titration, but with non-linear, i.e., curved, migration patterns in the spectra (Figure 7 and 8). The non-linear migration pattern of Δδ for T477, especially 1H shift above 50 mM Mg2+ concentration, is towards low-field in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration but towards high-field in the MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration. Such a difference in the titration patterns suggests that NaCl concentration or ionic strength affects the Mg2+ titration profile of T477. Our previous simulation studies suggested that T477 forms a transient hydrogen bond network with T472 or T473 to support the core of the protein 51. T477 is also adjacent to one of the active-site residues, E478, which coordinates metal ions. Based on these data and the previous result, the Mg2+ titration profile of T477 may reflect both changes in the hydrogen bond network as well as the effect of Mg2+ coordination at the active site. The non-linear, slight curved, migration pattern of Δδ was observed for Q500 in all the Mg2+ titration experiments. Since Q500 shows significant NaCl dependence of chemical shifts, the direction of which is similar to those of Mg2+ titration data, Q500 may sense both Mg2+ interactions at the active site and salt effects in the substrate handle region. Both T477 and Q500 are located close to the active site residues, E478 and D498, respectively. Through these inspections, it is apparent that even residues that exhibit significant Δδ upon Mg2+ titration are influenced by factors other than the direct Mg2+ interaction at the active site.

Mg2+ dissociation constant obtained by NMR

We selected 20 residues that satisfy the following criteria to evaluate KD: (A) those for which chemical shift changes at 80 mM Mg2+ were one-standard deviation larger than the average value among all the residues and (B) all data points in each titration curve that were detected without signal overlap (Figure 1A). KDs were calculated for these selected residues using a fit as described in the Experimental and Theoretical Methods (Table 1). The average KD for the residues in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration, 29.8 ± 5.0 mM, was significantly greater than those for the MgCl2(50NaCl) and MgCl2(const. Cl−) titrations (10–15 mM). Although practical error caused by pipetting error and sample instability were not taken into account, this larger KD in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration is consistent with the observed apparent low-affinity build-up of the Mg2+-bound form in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration compared to the others (Figure 6). In both MgCl2(0NaCl) and MgCl2(50NaCl) titrations, samples were prepared using the same 20 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.2. The 50 mM NaCl increases the pH by 0.04–0.05 unit (confirmed theoretically and experimentally), which would increase the KD of a divalent metal ion and is opposite to the observed larger KDs obtained for the MgCl2(0NaCl) condition compared to the MgCl2(50NaCl). Thus, the apparent low-affinity build up in the MgCl2(0NaCl) titration is not due to a pH shift caused by the lack of NaCl. Indeed, the KDs obtained in our MgCl2(50NaCl) and MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration experiments, 10 – 15 mM (Figure S4), are similar to the values reported previously 34, 35. The slightly larger KDs in our data, compared to others, are reasonably explained by a difference in the experimental pH: our experiments were performed at pH 7.2 whereas the experiments by the London and Maegley groups were carried out at pH 6.8 and pH 6.5, respectively 34, 35.

Table 1.

Average Mg2+ dissociation constants determined in three titration experiments.a

| Titration experiments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MgCl2(0NaCl) | MgCl2(50NaCl) | Mg2+(const. Cl−) | |

| KD (mM) | 29.8 ± 5.0 | 13.6 ± 2.5 | 12.3 ± 4.5 |

KD values were determined for 20 residues which satisfy two conditions: chemical shift changes at 80 mM Mg2+ were (A) above one-standard deviation of the average Δδ and (B) detected without signal overlap in the three datasets.

The observed KDs are higher than those obtained for the RNH domain in the full-length RT (KD, ~ 0.1 mM 36). There are two possible reasons for it. (I) The RNH structure is more rigid when it is incorporated as a part of the RT heterodimer 57, 58, 61, and, therefore, Mg2+ interaction with the full-length RT may be much stronger than the isolated RNH. (II) salt effects are not sufficiently separated from the effects of a specific Mg2+ interaction with RNH, resulting in a larger KD with the isolated RNH compared to full-length RT. In either case, this domain-level study is biologically significant since the RNH domain is exposed to the solvent in a RT precursor form 62. Our findings of various non-specific Mg2+ interaction effects precluded us from analyzing the titration data using a two-metal binding model.

Conclusions

Our aim in this study was to investigate molecular determinants of weak Mg2+ interaction with the protein. We successfully elucidated multiple factors that affect Mg2+ interaction to RNH, by comparing three different Mg2+ titration data sets. Careful analysis of these three sets of titration data, along with molecular dynamics simulation data of RNH with Na+ and Cl− ions, demonstrated two characteristic phenomena distinct from the specific Mg2+ interaction with the active site: (a) weak interaction of Mg2+, as a salt, with the substrate-handle region of the protein, (b) overall apparent lower affinity in the Mg2+ titration in the absence of NaCl compared to those in the presence of 50 mM NaCl. Taken together, these observations may suggest that the titrated MgCl2 is consumed as a salt and interacts with RNH not only specifically at the active site, but also in an unspecific fashion which modulates the RNH response. Therefore, in providing an overall landscape of a weak ligand interaction with a protein, the approach presented here may be widely applicable to usefully refine characterization of other complex ligand binding patterns, for instance in the context of drug discovery efforts and cell signaling studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM R01 105401 and AI R01 100890).

We thank Teresa Brosenitsch for critical reading of the manuscript and Michael Delk for NMR support. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM R01 105401 and AI R01 100890).

ABBREVIATIONS

- RNH

ribonuclease H

- HSQC

single-quantum coherence

- MgCl2(0NaCl)

MgCl2 titration in a 20 mM bisTris buffer (pH 7.2) in the absence of additional NaCl

- MgCl2(50NaCl)

MgCl2 titration in a 20 mM bisTris buffer (pH 7.2) in the presence of 50 mM NaCl

- MgCl2(const. Cl−)

Mg2+ titration in a 20 mM bisTris buffer at constant Cl− concentration

Footnotes

Supporting Information. A file that contains the following data is available free of charge: Table S1–S3, description of sample preparation; Figure S1, Comparison of Δδ values at 2, 5, 10, 20, and 50 mM Mg2+ versus those at 80 mM Mg2+ concentration; Figure S2, Plots of Δδ at the entire Mg2+ concentration range vs. the low Mg2+ concentration range; Figure S3, Comparison of HSQC spectral changes upon Mg2+ titration for the RNH residues at active site; Figure S4, KD determined from the MgCl2(50NaCl) and MgCl2(const. Cl−) titration data.

References

- 1.Weis WI, Drickamer K. Structural basis of lectin-carbohydrate recognition. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lis H, Sharon N. Lectins: Carbohydrate-specific proteins that mediate cellular recognition. Chem Rev. 1998;98:637–674. doi: 10.1021/cr940413g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang PH, Wang SK, Wong CH. Quantitative analysis of carbohydrate-protein interactions using glycan microarrays: Determination of surface and solution dissociation constants. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11177–11184. doi: 10.1021/ja072931h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudev T, Lim C. Metal binding affinity and selectivity in metalloproteins: insights from computational studies. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:97–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwaller B. Cytosolic Ca2+ buffers. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a004051. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao Z, Wedd AG. The challenges of determining metal-protein affinities. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:768–789. doi: 10.1039/b906690j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arakawa T, Timasheff SN. Mechanism of Protein Salting in and Salting out by Divalent-Cation Salts - Balance between Hydration and Salt Binding. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5912–5923. doi: 10.1021/bi00320a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timasheff SN. Protein-solvent preferential interactions, protein hydration, and the modulation of biochemical reactions by solvent components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9721–9726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122225399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roosen-Runge F, Heck BS, Zhang F, Kohlbacher O, Schreiber F. Interplay of pH and binding of multivalent metal ions: charge inversion and reentrant condensation in protein solutions. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:5777–5787. doi: 10.1021/jp401874t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohlson S, Jungar C, Strandh M, Mandenius CF. Continuous weak-affinity immunosensing. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fielding L. NMR methods for the determination of protein-ligand dissociation constants. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 2007;51:219–242. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins JR, Diboun I, Dessailly BH, Lees JG, Orengo C. Transient protein-protein interactions: structural, functional, and network properties. Structure. 2010;18:1233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acuner Ozbabacan SE, Engin HB, Gursoy A, Keskin O. Transient protein-protein interactions. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2011;24:635–48. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzr025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinogradova O, Qin J. NMR as a unique tool in assessment and complex determination of weak protein-protein interactions. Top Curr Chem. 2012;326:35–45. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson MP. Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 2013;73:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fielding L. NMR methods for the determination of protein-ligand dissociation constants. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:39–53. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shortridge MD, Hage DS, Harbison GS, Powers R. Estimating protein-ligand binding affinity using high-throughput screening by NMR. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:948–58. doi: 10.1021/cc800122m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cala O, Guilliere F, Krimm I. NMR-based analysis of protein-ligand interactions. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406:943–956. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-6931-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellecchia M. Solution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Techniques for Probing Intermolecular Interactions. Chem Biol. 2005;12:961–971. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishima R. Protein-Inhibitor Interaction Studies Using NMR. Appl NMR Spectrosc. 2015;1:143–181. doi: 10.2174/9781608059621115010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldflam M, Tarrago T, Gairi M, Giralt E. NMR studies of protein-ligand interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;831:233–259. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-480-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DB Viral Rna-Dependent DNA Polymerase - Rna-Dependent DNA Polymerase in Virions of Rna Tumour Viruses. Nature. 1970;226:1209–1211. doi: 10.1038/2261209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Temin HM, Mizutani S. Viral Rna-Dependent DNA Polymerase - Rna-Dependent DNA Polymerase in Virions of Rous Sarcoma Virus. Nature. 1970;226:1211–1213. doi: 10.1038/2261211a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markin CJ, Spyracopoulos L. Increased precision for analysis of protein–ligand dissociation constants determined from chemical shift titrations. J Biomol NMR. 2012;53:125–138. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9630-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markin CJ, Spyracopoulos L. Accuracy and precision of protein–ligand interaction kinetics determined from chemical shift titrations. J Biomol NMR. 2012;54:355–376. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9678-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovrigin EL. NMR line shapes and multi-state binding equilibria. J Biomol NMR. 2012;53:257–270. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConnell HM. Reaction Rates by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J Chem Phys. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long D, Yang D. Buffer interference with protein dynamics: a case study on human liver fatty acid binding protein. Biophys J. 2009;96:1482–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortega R, Perez JAL, Nicklasson PJ, Sira-Ramirez H. Passivity-based Control of Euler-Lagrange Systems: Mechanical, Electrical and Electromechanical Applications. Springer; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong M, Khirich G, Loria JP. What’s in your buffer? Solute altered millisecond motions detected by solution NMR. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6548–6558. doi: 10.1021/bi400973e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozlyuk N, Sengupta S, Luptak A, Martin RW. In situ NMR measurement of macromolecule-bound metal ion concentrations. J Biomol NMR. 2016;64:269–273. doi: 10.1007/s10858-016-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christen MT, Menon L, Myshakina NS, Ahn J, Parniak MA, Ishima R. Structural Basis of the Allosteric Inhibitor Interaction on the HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase RNase H Domain. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;80:706–716. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pari K, Mueller GA, DeRose EF, Kirby TW, London RE. Solution structure of the RNase H domain of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in the presence of magnesium. Biochemistry. 2003;42:639–650. doi: 10.1021/bi0204894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan J, Wu H, Tom T, Brodsky O, Maegley K. Targeting divalent metal ions at the active site of the HIV-1 RNase H domain: NMR studies on the interactions of divalent metal ions with RNase H and its inhibitors. Am J Anal Chem. 2011;2:639. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowan JA, Ohyama T, Howard K, Rausch JW, Cowan SM, Le Grice SF. Metal-ion stoichiometry of the HIV-1 RT ribonuclease H domain: evidence for two mutually exclusive sites leads to new mechanistic insights on metal-mediated hydrolysis in nucleic acid biochemistry. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2000;5:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s007750050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldschmidt V, Didierjean J, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Isel C, Marquet R. Mg2+ dependency of HIV-1 reverse transcription, inhibition by nucleoside analogues and resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:42–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arts EJ, Le Grice SFJ. Interaction of Retroviral Reverse Transcriptase with Template–Primer Duplexes during Replication. In: Kivie M, editor. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. Vol. 58. Academic Press; 1997. pp. 339–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotte M, Fackler S, Hermann T, Perola E, Cellai L, Gross HJ, Le Grice SF, Heumann H. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-associated RNase H cleaves RNA/RNA in arrested complexes: implications for the mechanism by which RNase H discriminates between RNA/RNA and RNA/DNA. EMBO J. 1995;14:833–841. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schultz SJ, Champoux JJ. RNase H activity: Structure, specificity, and function in reverse transcription. Virus Res. 2008;134:86–103. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang W, Lee JY, Nowotny M. Making and Breaking Nucleic Acids: Two-Mg2+-Ion Catalysis and Substrate Specificity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies JF, Hostomska Z, Hostomsky Z, Matthews D. Crystal structure of the ribonuclease H domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1991;252:88–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1707186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schatz O, Cromme FV, Gruninger-Leitch F, Le Grice SF. Point mutations in conserved amino acid residues within the C-terminal domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase specifically repress RNase H function. FEBS Lett. 1989;257:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizrahi V, Brooksbank RL, Nkabinde NC. Mutagenesis of the conserved aspartic acid 443, glutamic acid 478, asparagine 494, and aspartic acid 498 residues in the ribonuclease H domain of p66/p51 human immunodeficiency virus type I reverse transcriptase. Expression and biochemical analysis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19245–19249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tadokoro T, Kanaya S. Ribonuclease H: molecular diversities, substrate binding domains, and catalytic mechanism of the prokaryotic enzymes. FEBS J. 2009;276:1482–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steitz TA, Steitz JA. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klumpp K, Hang JQ, Rajendran S, Yang Y, Derosier A, Wong Kai In P, Overton H, Parkes KE, Cammack N, Martin JA. Two-metal ion mechanism of RNA cleavage by HIV RNase H and mechanism-based design of selective HIV RNase H inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6852–6859. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W. Crystal Structures of RNase H Bound to an RNA/DNA Hybrid: Substrate Specificity and Metal-Dependent Catalysis. Cell. 2005;121:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowotny M, Yang W. Stepwise analyses of metal ions in RNase H catalysis from substrate destabilization to product release. EMBO J. 2006;25:1924–1933. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beilhartz GL, Gotte M. HIV-1 Ribonuclease H: Structure, Catalytic Mechanism and Inhibitors. Viruses. 2010;2:900–926. doi: 10.3390/v2040900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slack RL, Spiriti J, Ahn J, Parniak MA, Zuckerman DM, Ishima R. Structural integrity of the ribonuclease H domain in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Proteins. 2015;83:1526–1538. doi: 10.1002/prot.24843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris RK, Becker ED, Cabral de Menezes SM, Granger P, Hoffman RE, Zilm KW. Further conventions for NMR shielding and chemical shifts (IUPAC Recommendations 2008) Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2008:80. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–8. 27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueller GA, Pari K, DeRose EF, Kirby TW, London RE. Backbone Dynamics of the RNase H Domain of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9332–9342. doi: 10.1021/bi049555n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powers R, Clore GM, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Gronenborn A. Analysis of the backbone dynamics of the ribonuclease H domain of the human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase using nitrogen-15 relaxation measurements. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9150–9157. doi: 10.1021/bi00153a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobo-Molina A, Ding J, Nanni RG, Clark AD, Lu X, Tantillo C, Williams RL, Kamer G, Ferris AL, Clark P. Crystal structure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase complexed with double-stranded DNA at 3.0 A resolution shows bent DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6320–6324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kohlstaedt L, Wang J, Friedman J, Rice P, Steitz T. Crystal structure at 3.5 A resolution of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an inhibitor. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katayanagi K, Miyagawa M, Matsushima M, Ishikawa M, Kanaya S, Ikehara M, Matsuzaki T, Morikawa K. Three-dimensional structure of ribonuclease H from E. coli. Nature. 1990;347:306–309. doi: 10.1038/347306a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stroppolo ME, Falconi M, Caccuri AM, Desideri A. Superefficient enzymes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1451–1460. doi: 10.1007/PL00000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng X, Mueller GA, DeRose EF, London RE. Metal and ligand binding to the HIV-RNase H active site are remotely monitored by Ile556. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40:10543–10553. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharaf NG, Poliner E, Slack RL, Christen MT, Byeon IJ, Parniak MA, Gronenborn AM, Ishima R. The p66 immature precursor of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Proteins. 2014;82:2343–2352. doi: 10.1002/prot.24594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.