Abstract

Background

The Gail model has been widely used and validated with conflicting results. The current study aims to evaluate the performance of different versions of the Gail model by means of systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis (TSA).

Methods

Three systematic review and meta-analyses were conducted. Pooled expected-to-observed (E/O) ratio and pooled area under the curve (AUC) were calculated using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model. Pooled sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds ratio were evaluated by bivariate mixed-effects model. TSA was also conducted to determine whether the evidence was sufficient and conclusive.

Results

Gail model 1 accurately predicted breast cancer risk in American women (pooled E/O = 1.03; 95% CI 0.76–1.40). The pooled E/O ratios of Caucasian-American Gail model 2 in American, European and Asian women were 0.98 (95% CI 0.91–1.06), 1.07 (95% CI 0.66–1.74) and 2.29 (95% CI 1.95–2.68), respectively. Additionally, Asian-American Gail model 2 overestimated the risk for Asian women about two times (pooled E/O = 1.82; 95% CI 1.31–2.51). TSA showed that evidence in Asian women was sufficient; nonetheless, the results in American and European women need further verification.

The pooled AUCs for Gail model 1 in American and European women and Asian females were 0.55 (95% CI 0.53–0.56) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.63–0.88), respectively, and the pooled AUCs of Caucasian-American Gail model 2 for American, Asian and European females were 0.61 (95% CI 0.59–0.63), 0.55 (95% CI 0.52–0.58) and 0.58 (95% CI 0.55–0.62), respectively.

The pooled sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds ratio of Gail model 1 were 0.63 (95% CI 0.27–0.89), 0.91 (95% CI 0.87–0.94) and 17.38 (95% CI 2.66–113.70), respectively, and the corresponding indexes of Gail model 2 were 0.35 (95% CI 0.17–0.59), 0.86 (95% CI 0.76–0.92) and 3.38 (95% CI 1.40–8.17), respectively.

Conclusions

The Gail model was more accurate in predicting the incidence of breast cancer in American and European females, while far less useful for individual-level risk prediction. Moreover, the Gail model may overestimate the risk in Asian women and the results were further validated by TSA, which is an addition to the three previous systematic review and meta-analyses.

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42016047215.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13058-018-0947-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Gail model, Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Trial sequential analysis

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women with high morbidity and mortality rates [1]. Risk assessment tools estimating the individual’s absolute risk for developing breast cancer and identifying the women at high level of risk are crucial for decision-making about prevention and screening.

The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BCRAT) [2], also known as the Gail model, was the most widely used appraisal tool for predicting the absolute risk of developing breast cancer. Individuals with 5-year risk exceeding 1.67% were considered high risk [3]. In 1992, the tool was modified to specifically predict invasive breast cancer, and this updated model, referred to as Gail model 2 (Caucasian-American Gail model) [4], has been used for determining the eligibility of subjects for chemoprevention of invasive breast cancer [5, 6]. In addition, this modified Gail model was also updated subsequently to predict the risk for other ethnic populations, such as African-American [7] and Asian-American [8] females.

A number of studies have been conducted to validate the Gail model in American [9–27], European [28–37], Asian [38–50] and Oceanian [51, 52] women. However, these studies showed variability in their calibration (expected-to-observed (E/O) ratio) and discrimination (Concordance-statistic (C-statistic) or area under the curve (AUC)). Although three systematic review and meta-analyses validated the Gail model previously [53–55], 19 studies [13, 14, 17–20, 22–24, 32–36, 38, 40, 41, 51, 52] with inconsistent results have been published subsequently or were not included in the previous meta-analyses. However, the evaluation studies launched in China [39, 42–50] have not been incorporated before and the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model has not been fully evaluated.

There is increasing awareness that a meta-analysis also needs sufficient sample size to get a stable conclusion. Trial sequential analysis (TSA) was introduced to calculate the required information size (RIS) for meta-analysis and to decide whether the evidence was sufficient and conclusive [56, 57].

Here, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the performance of different versions of the Gail model from three different dimensions (calibration, discrimination and diagnostic accuracy). In addition, the meta-analysis for calibration of the Gail model was also challenged by TSA.

Methods

Study registration

The current systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to MOOSE guidelines [58] and has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42016047215).

Literature search strategy

Two investigators conducted a literature search in the PubMed, Embase, WANFANG [59], VIP [60] and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) [61] databases for all articles concerning the performance of the Gail model in females.

We used “mammary OR breast cancer OR carcinoma OR tumor OR neoplasm” AND “calibration OR validate OR validation OR screen OR screening OR expected-to-observed ratio OR E/O ratio” AND “Gail model OR breast cancer risk assessment tool OR BCRAT” as medical subject headings (MeSH) in searching for studies evaluating the calibration of the Gail model.

The terms “mammary OR breast cancer OR carcinoma OR tumor OR neoplasm” AND “discrimination OR validate OR validation OR screen OR screening OR sensitivity OR specificity OR area under the curve OR AUC OR C-statistic” AND “Gail model OR breast cancer risk assessment tool OR BCRAT” were used for retrieving publications assessing the discrimination and diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model.

Publications in English and Chinese language between 1 January 1989 (when the Gail model was developed [3]) and 31 July 2016 were included. Listed references were also manually checked for relevant papers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis included the following: studies validating the performance of the original (Gail model 1) or modified (Gail model 2) Gail model in women [3, 4]; calibration of the Gail model was prospectively estimated focusing on cohort studies that provided the E/O ratio and its 95% confidence interval (CI) or offered sufficient data for calculating the expected and observed number of breast cancer; discrimination of the Gail model was estimated focusing on the studies providing the C-statistic or AUC and its 95% CI for the Gail model; the diagnostic meta-analysis included publications that provided sufficient data for calculating the true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN) and true negative (TN) values of the Gail model, respectively; the threshold of the Gail model was limited to ≥ 1.67%; the sample size should be higher than 100 and the mean follow-up period for the cohort studies should be longer than 1 year; and when multiple publications included the same population, studies with larger sample size or longer follow-up period were incorporated and studies with independent validations in subsequent articles were included.

Literature selection for the systematic review and meta-analysis

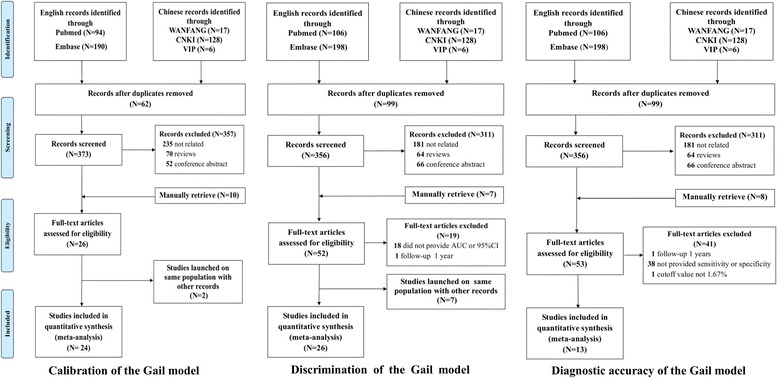

For the calibration of the Gail model, 435 studies were found in the electronic databases and 10 were manually retrieved. After careful examination, 419 publications were excluded: 62 were duplicated records, 235 were not related, 70 were reviews and 52 were conference abstracts. In addition, two studies were excluded [27, 62] as they focused on the same population but with smaller sample size than other studies [17, 31]. In the end, 24 studies with 29 datasets were included.

After excluding the duplicated records, 356 studies were retrieved for estimating the discrimination of the Gail model. Of these, 311 were excluded in the preliminary screening and 19 were further eliminated by full-text reading. Moreover, seven studies [31, 62–67] were also excluded as they focused on the same population but with a shorter study period or smaller sample size than other included studies [17, 27, 51]. In total, 26 studies incorporating 29 datasets were included in this meta-analysis.

For the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model, 455 publications were retrieved at the beginning. After preliminary screening and the full-text reading, 13 studies were finally included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection in the meta-analyses for estimating the calibration, discrimination and diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model. AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, CNKI China National Knowledge Infrastructure

Studies included in the aforementioned three meta-analyses overlapped to some extent, as some of them provided both the E/O ratio and AUC or the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model [11, 15, 17, 18, 20, 30–33, 35, 39, 41, 44, 45].

Data abstraction

Two investigators independently extracted data. Relevant information included the first author, publication year, geographic region, versions of the Gail model (Gail model 1 or Gail model 2 for Caucasian-American, Asian-American and African-American women), risk prediction period, study design, study population, sample size, mean age of participants as well as the risk for breast cancer, study period, follow-up period, E/O ratio with 95% CI, C-statistic or AUC with 95% CI and number of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN) and true negative (TN) values. The quality of the included studies was assessed by Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [68] and the studies incorporated in the diagnostic meta-analysis were assessed by Quality Assessment Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) [69]. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and where needed the corresponding author was contacted.

Statistical analyses

Calibration assessed how closely the number of subjects predicted to develop breast cancer matched the observed number of breast cancer cases diagnosed during a specific period. This was calculated by E/O ratio and the 95% CI of the E/O ratio was computed as: E/O ratio × exp.(± 1.96 × 1/√(O)) [11]. A well-fitting calibration should be close to 1.0. The discrimination value was assessed by C-statistic, which measures the Gail model’s ability to discriminate the women who will and will not develop breast cancer; moreover, it was considered identical to the AUC in the current study [54]. A C-statistic/AUC of 0.5 was considered as no discrimination, whereas 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination.

The pooled E/O ratio and C-statistic/AUC of the Gail model were calculated using DerSimonian and Laird’s random-effects model [70]. The I2 value was employed to evaluate the heterogeneity among the studies, and subgroup analyses were carried out to identify the source of the heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the influence of each study on the combined effects by sequentially omitting each dataset [71]. Cumulative meta-analyses were launched to investigate the trend of the pooled E/O ratio and C-statistic/AUC ranked by the publication year and sample size [72]. Visualized asymmetry of the funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were assessed to detect publication bias. Pooled effects were also adjusted by the Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method [73–75].

The pooled estimations of sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were calculated using a bivariate mixed-effects model. The DOR is the ratio of risk odds in breast cancer cases relative to that in controls [76]. Publication bias was detected by Deeks’ funnel plot, using 1/root (effective sample size) vs log DOR. P < 0.05 for the slope coefficient indicates significant asymmetry [77].

In the current study, TSA was conducted to determine whether the sample size incorporated in the meta-analysis was sufficient for evaluating the calibration of the Gail model. The included cohort studies are identified as trials for calculating the difference in breast cancer incidence between the expected and observed groups, and accordingly the total sample size is doubled. For the TSA, when the Z-curve crosses the conventional boundary, a significant difference is considered to exist between the expected group and the observed group for breast cancer incidence. Moreover, if the Z-curve passes through the trial sequential monitoring boundary or required information size (RIS) boundary, the evidence is considered sufficient and conclusive. Otherwise, the evidence is adjudged inconclusive and more studies were required to further verify the results [56, 57]. Furthermore, in order to evaluate the effect of the Chinese studies on the performance of the Gail model, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by eliminating the studies retrieved from the WANFANG, VIP and CNKI databases.

Pooled E/O ratio and AUC were synthesized using Comprehensive Meta Analysis version 2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR were conducted with Stata statistical software version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The trial sequential analyses program (version 0.9 beta) was used for the TSA [78] (Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011).

Results

Calibration of the Gail model

Twenty-four studies incorporating 29 records were included to evaluate the calibration of the Gail model [9–20, 28–35, 38, 39, 41, 52] (Table 1). The pooled E/O ratio was 1.16 (95% CI 1.05–1.30) with a high level of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 98.8%; p < 0.01) (Fig. 2a). Sensitivity analysis showed that the combined E/O ratio and 95% CI were not significantly altered before and after the omission of each dataset (see Additional file 1A). Cumulative analysis showed that by continually increasing the publication year and the sample size, the 95% CI became narrower and the pooled E/O ratio was closer to 1.0, which indicates that the precision of the pooled E/O ratio was gradually improved (see Additional file 1B, C). Publication bias was detected by funnel plot (regression coefficient = 5.38; p = 0.027) (see Additional file 2A). According to the trim-and-fill method, the adjusted pooled E/O ratio was 1.25 (95% CI 1.11–1.40) after trimming (see Additional file 2B).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies for estimating the calibration of the Gail model

| Reference | Author | Publication year | Geographic background | Gail model version | 5/10-year risk | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Study population | Risk for breast cancera | Time period | Follow-up period | E/O (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Bondy | 1994 | America | 1 | 5 | 1981 | 30–75 | American Cancer Society 1987 Texas Breast Screening Project (with family history of breast cancer) | High risk | 1987–1992 | 5.0 | 1.31 (0.96–1.79) |

| [10] | Spiegelman | 1994 | America | 1 | 5 | 115,172 | 29–61 | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | General population | 1976–1981 | 6.0 | 1.33 (1.28–1.39) |

| [12] | Costantino-1 | 1999 | America | 1 | 5 | 5969 | > 35 | Placebo group of Breast cancer prevention trial (BCPT) | General population | 1992–1998 | 4.03 (0.1–5.83) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) |

| [12] | Costantino-2 | 1999 | America | 2 | 5 | 5969 | > 35 | Placebo group of Breast cancer prevention trial (BCPT) | General population | 1992–1998 | 4.03 (0.1–5.83) | 1.03 (0.88–1.21) |

| [11] | Rockhill | 2001 | America | 2 | 5 | 82,109 | 45–71 | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | General population | 1992–1997 | 5.0 | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) |

| [30] | Amir | 2003 | United Kingdom | 2 | 10 | 3150 | 44 (21–73) | Women attending the Family History Screening Programme in University Hospital of South Manchester | Not defined | 1987–2001 | 5.27 (0.1–15) | 0.69 (0.54–0.90) |

| [13] | Bernatsky | 2004 | America | 1 | 5 | 871 | 41 ± 13 | Systemic lupus erythematosus clinic cohorts at Canada, Northwestern and UK center | High risk | 1984–2000 | 9.1 | 0.48 (0.29–0.80) |

| [14] | Olson | 2004 | America | 1 | 5 | 674 | 31–90 | Women with possible bilateral oophorectomy identified from the Mayo Clinic Surgical Index | Low risk | 1994–2004 | NA | 1.37 (0.92–2.04) |

| [28] | Boyle | 2004 | Italy | 2 | 5 | 5383 | NA | Women participated in RCT of tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention in Italy | General population | 1992–2001 | 5.0 | 1.16 (0.89–1.49) |

| [29] | Decarli | 2006 | Italy | 2 | 5 | 10,031 | 35–64 | Florence—European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort (EPIC) | General population | 1993–2002 | 9.0 | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) |

| [31] | Chlebowski | 2007 | America | 2 | 5 | 147,916 | 63 (50–79) | Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) | General population | 1993–2005 | 5.0 | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

| [15] | Tice | 2008 | America | 2 | 5 | 629,229 | 40–74 | National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) | General population | since 1994 | 5.3 | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) |

| [16] | Schonfeld-1 | 2010 | America | 2 | 5 | 181,979 | 62.8 | National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons (NIH-AARP) | General population | 1995–2003 | 7.5 | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) |

| [16] | Schonfeld-2 | 2010 | America | 2 | 5 | 64,868 | 62.3 | Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) | General population | 1993–2006 | 8.6 | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) |

| [17] | Tarabishy | 2011 | America | 2 | 5 | 4726 | 18–85 | Mayo Benign Breast Disease (BBD) | High risk | 1991–1996 | 5.0 | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) |

| [38] | Chay-1 | 2012 | Singapore | 3 | 5 | 28,104 | 50–64 | Singapore Breast Cancer Screening Project (SBCSP) | General population | 1997–2007 | 5.0 | 2.51 (2.14–2.96) |

| [38] | Chay-2 | 2012 | Singapore | 3 | 10 | 28,104 | 50–64 | Singapore Breast Cancer Screening Project (SBCSP) | General population | 1997–2007 | 10.0 | 1.85 (1.68–2.04) |

| [52] | Maclnnis | 2012 | Australia | NA | NA | 2000 | NA | Female relatives of the breast cancer cases in Australia | High risk | NA | 10.0 | 0.89 (0.73–1.09) |

| [32] | Pastor-Barriuso | 2013 | Spain | 2 | 5 | 54,649 | 45–68 | Population-based Navarre Breast Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) | General population | 1996–2005 | 7.7 | 1.46 (1.36–1.56) |

| [33] | Buron | 2013 | Spain | 2 | 5 | 2200 | 49–64 | Participants with a positive screening mammogram in “Parc de Salut Mar” breast cancer screening program | High risk | 2003–2010 | 6.0 | 0.58 (0.54–0.63) |

| [41] | Min-1 | 2014 | Korea | 2 | 5 | 40,229 | > 10 | Women routinely screened in Women’s Healthcare Center of Cheil General Hospital | Not defined | 1999–2004 | 5.0 | 2.46 (2.10–2.87) |

| [41] | Min-2 | 2014 | Korea | 3 | 5 | 40,229 | > 10 | Women routinely screened in Women’s Healthcare Center of Cheil General Hospital | Not defined | 1999–2004 | 5.0 | 1.29 (1.11–1.51) |

| [18] | Powell | 2014 | America | 2 | 5 | 12,843 | NA | Marin Women’s Study with high rate of breast cancer, null parity and delayed childbirth | High risk | 2003–2007 | 5.0 | 0.81 (0.71–0.93) |

| [19] | McCarthy | 2015 | America | 2 | 5 | 464 | 48.7 ± 13.2 | Women referred for biopsy with abnormal (Breast Imaging Reporting And Data System, BI-RADS 4) mammograms at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania | High risk | 2003–2012 | 5.0 | 3.78 (2.78–5.13) |

| [34] | Dartois | 2015 | France | 2 | 5 | 13,174 | 42–72 | Women in French E3N prospective cohort to investigate the cancer risk factors | General population | 1993–1998 | 5.0 | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) |

| [39] | Hu | 2015 | China | 2 | 5 | 42,908 | 35–69 | Women participated in the breast cancer screening in Zhejiang eastern coastal areas of China | General population | 2008–2014 | 5.0 | 2.09 (1.73–2.52) |

| [20] | Schonberg-1 | 2015 | America | 2 | 5 | 71,293 | 70 ± 7.0 | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | High risk | 2004–2009 | 5.0 | 1.20 (1.13–1.26) |

| [20] | Schonberg-2 | 2015 | America | 2 | 5 | 79,611 | 71 ± 6.8 | Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), extensive study | High risk | 2005–2010 | 5.0 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) |

| [35] | Brentnall | 2015 | United Kingdom | 2 | 10 | 50,628 | 47–73 | 15 screening areas in Greater Manchester, UK | General population | 2009–2014 | 3.2 | 2.67 (2.46–2.90) |

Note: Gail model type 1, original Gail model; Gail model type 2, modified Gail model for Caucasian-American; Gail model type 3, modified Gail model for Asian-American

NA not available, E/O expected-to-observed ratio, CI confidence interval, RCT randomized controlled trial

aCohort studies enrolled women with high risk for breast cancer (with higher average age (> 70 years), dense mammary image, postmenopausal state, breast cancer relatives or high rate of delayed childbirth) were defined as “High risk”; cohort studies that did not accurately depict the characteristics of the participants were defined as “Not defined”. Participants with protective factors for breast cancer were considered low risk

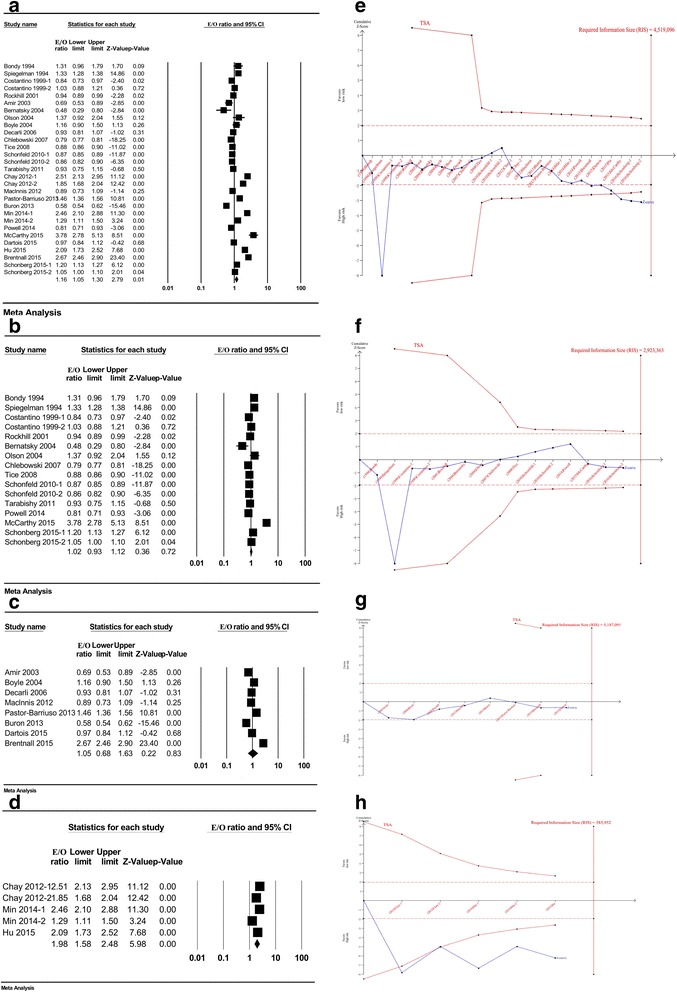

Fig. 2.

Calibration of the Gail model in total and stratified by geographic region with the trial sequential analysis. Forest plot of the pooled E/O ratio for the Gail model in total (a) and studies from America (b), Europe (c) and Asia (d), respectively. Trial sequential analysis (TSA) for pooled E/O ratio in total (e) and studies from America (f), Europe (g) and Asia (g), respectively. E/O expected-to-observed ratio, CI confidence interval

Subgroup analysis suggested the geographic region (see Additional file 3) could partly explain the heterogeneities between these studies (p < 0.01). The Gail model exhibited a tendency to overpredict breast cancer risk for Asian women (pooled E/O = 1.98; 95% CI 1.58–2.48) compared to American (pooled E/O = 1.02; 95% CI 0.93–1.12) and European (pooled E/O = 1.05; 95% CI 0.68–1.63) women (Fig. 2b–d). Publication bias did not exist in each of these subgroups (see Additional file 4).

In addition, results showed that Gail model 1 accurately predicted breast cancer risk in American women (pooled E/O = 1.03; 95% CI 0.76–1.40). However, Gail model 2 overpredicted the risk for breast cancer (pooled E/O = 1.20; 95% CI 1.07–1.35) (see Additional file 3). When further stratified by different versions of Gail model 2, the pooled E/O ratios of Caucasian-American Gail model 2 in American [11, 12, 15–20, 31], European [28–30, 32–35] and Asian [39, 41] women were 0.98 (95% CI 0.91–1.06), 1.07 (95% CI 0.66–1.74) and 2.29 (95% CI 1.95–2.68), respectively. The pooled E/O ratio for Asian women was significantly higher than that in American and European females (p < 0.001). Moreover, only two studies clearly stated that they used the Asian-American Gail model [38, 41], and the results indicated that it overestimated the risk for Asian women about two times (pooled E/O = 1.82; 95% CI 1.31–2.51) (see Additional file 5).

When excluding studies conducted in Asian women [38, 39, 41], results showed that the Gail model precisely predicted the risk for developing breast cancer (pooled E/O = 1.04; 95% CI 0.93–1.16) (see Additional file 6A). Sensitivity analysis by singly eliminating each study showed no significant fluctuation, which indicated the stability of the results (see Additional file 6B). Cumulative analysis showed that the pooled E/O ratio became progressively closer to 1.0 according to accumulation of the publication year and sample size (see Additional file 6C, D). When stratified by different versions of the Gail model, the combined E/O ratios of Gail model 1 and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 were reported to be 1.03 (95% CI 0.76–1.40) and 1.05 (95% CI 0.93–1.17), respectively, with no significant difference (p = 0.93) (see Additional file 7). Stratified analysis showed that the studies with high reporting quality were prone to have a precise estimate of breast cancer risk (pooled E/O = 0.88; 95% CI 0.71–1.10 vs pooled E/O = 1.13; 95% CI 1.00–1.29; p = 0.06). However, no difference was found when stratified by the geographic region and other factors (see Additional file 8).

Trial sequential analysis

In the TSA, the cumulative Z-curve passed through both the conventional and the trial sequential monitoring boundary, which suggested the evidence was sufficient to verify the overprediction of the Gail model (Fig. 2e). When stratified by geographic region, the cumulative Z-curve did not cross the conventional and RIS boundary in American (Fig. 2f) and European (Fig. 2g) studies, demonstrating the accurate prediction of the Gail model. However, the evidence was insufficient to draw a firm conclusion and more related studies were required to confirm the results. With respect to Asian women, the Z-score crossed both the conventional and TSA-adjusted boundary, which showed the overestimation of breast cancer risk in Asian females and the evidence was sufficient and conclusive (Fig. 2h).

Discrimination of the Gail model

Twenty-six articles with 29 datasets describing the C-statistic/AUC of the Gail model were combined to evaluate its pooled discrimination [11, 15, 18–24, 27, 29–32, 34–36, 39–46, 51] (Table 2). The pooled AUC was 0.60 (95% CI 0.58–0.62) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 97.0%; p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a). Sensitivity analysis suggested that the results were stable, and cumulative analysis indicated that the 95% CI became narrower and the pooled AUC progressively rose toward 0.60 with the accumulation of data ranked by publication year and sample size (see Additional file 9A–C).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies for estimating the discrimination of the Gail model

| Reference | Author | Publication year | Geographic background | Study design | Gail model version | 5/10-year risk | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Study population | Risk for breast cancera | Time period | Follow-up period | C-statistic/AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | Rockhill | 2001 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 82,109 | 45–71 | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | General population | 1992–1997 | 5.0 | 0.58 (0.56–0.60) |

| [30] | Amir | 2003 | United Kingdom | Cohort | 2 | 10 | 3150 | 21–73 | Women attending the Family History Screening Programme in University Hospital of South Manchester | Not defined | 1987–2001 | 5.0 | 0.74 (0.67–0.80) |

| [21] | Tice | 2005 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 81,777 | 55.9 | Community-based registry San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR) | General population | 1993–2002 | 5.1 (0.1–15) | 0.67 (0.65–0.68) |

| [29] | Decarli | 2006 | Italy | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 10,031 | 35–64 | Florence—European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition cohort (EPIC) | General population | 1993–2002 | 9.0 | 0.59 (0.55–0.63) |

| [36] | Crispo | 2008 | Italy | Case–control | 1 | 5 | 1765 | 53.7 | National Cancer Institute of Naples (southern Italy) | NA | 1997–2000 | NA | 0.55 (0.53–0.58) |

| [15] | Tice | 2008 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 251,789 | 40–74 | National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) | General population | since 1994 | 5.3 | 0.61 (0.60–0.62) |

| [42] | Pan | 2009 | China | Cross-sectional | 1 | 5 | 2133 | > 35 | Breast cancer risk assessment, evaluation and health education program, in Beijing and Guangzhou community | NA | 2006–2007 | NA | 0.64 (0.61–0.67) |

| [43] | Liu | 2010 | China | Cross-sectional | 2 | 5 | 246 | 49.82 | High-risk breast cancer screening model and chemical intervention study at the community level | NA | 2007–2009 | NA | 0.56 (0.49–0.64) |

| [44] | Wang | 2010 | China | Case–control | 1 | 5 | 228 | 32–75 | Shenzhou Hospital of Shenyang Medical College-based breast cancer cases and control | NA | 1998–2007 | NA | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) |

| [17] | Tarabishy | 2011 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 4726 | 18–85 | Mayo Benign Breast Disease (BBD) | High risk | 1982–1991 | 16.2 | 0.64 (0.62–0.66) |

| [22] | Vacek | 2011 | America | Cohort | 1 | 5 | 19,779 | > 70 | Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System (VBCSS) | High risk | 2001–2009 | 7.1 | 0.54 (0.52–0.56) |

| [27] | Banegas | 2012 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 128,976 | 63.51 | Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) | General population | 1993–2005 | 5.0 | 0.58 (0.57–0.59) |

| [23] | Quante | 2012 | America | Cohort | 2 | 10 | 1857 | 44 | Women with high risk for breast or ovarian cancer in New York site of the Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR) | High risk | 1995–2011 | 8.1 | 0.63 (0.58–0.69) |

| [32] | Pastor-Barriuso | 2013 | Spain | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 54,649 | 45–68 | Population-based Navarre Breast Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) | General population | 1996–2005 | 7.7 | 0.54 (0.52–0.57) |

| [51] | Dite | 2013 | Australia | Case–control | 2 | 5 | 1425 | 45.4 | Cases and controls from the Australian Breast Cancer Family Registry (ABCFR) | NA | 1992–1998 | NA | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) |

| [40] | Anothaisintawee | 2013 | Thailand | Cross-sectional | NA | NA | 15,718 | NA | Ramathibodi Hospital and two tertiary hospitals | NA | 2011–2013 | NA | 0.41 (0.36–0.46) |

| [24] | Ronser | 2013 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 11,419 | 54.0 ± 3.3 | Postmenopausal women in California Teachers Study (CTS) | High risk | 1995–2009 | 5.0 | 0.55 (0.53–0.56) |

| [41] | Min-1 | 2014 | Korea | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 40,229 | > 10 | Breast cancer screening patients routinely screened in Women’s Healthcare Center of Cheil General Hospital | Not defined | 1999–2004 | 5 | 0.55 (0.50–0.59) |

| [41] | Min-2 | 2014 | Korea | Cohort | 3 | 5 | 40,229 | > 10 | Breast cancer screening patients routinely screened in Women’s Healthcare Center of Cheil General Hospital | Not defined | 1999–2004 | 5 | 0.54 (0.50–0.59) |

| [18] | Powell | 2014 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 12,843 | NA | Marin Women’s Study with high rate of breast cancer, null parity and delayed childbirth | High risk | 2003–2007 | 7.7 | 0.62 (0.59–0.66) |

| [45] | Duan | 2014 | China | Case–control | 2 | 5 | 400 | 35–74 | Breast cancer cases and controls in the First Affiliate Hospital of KunMing Medical University | NA | 2007–2011 | NA | 0.54 (0.49–0.60) |

| [19] | McCarthy | 2015 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 464 | 48.7 ± 13 | Women referred for biopsy with abnormal (Breast Imaging Reporting And Data System, BI-RADS 4) mammograms at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania | High risk | 2003–2012 | 5.0 | 0.71 (0.65–0.78) |

| [34] | Dartois-1 | 2015 | France | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 5843 | 42–72 | Premenopausal Women in French E3N (E´ tude E´ pide´miologique aupre`s des femmes de laMutuelle Ge´ne´rale de l’E´ ducation Nationale (MGEN)) prospective cohort to investigate the cancer risk factors | General population | 1993–1998 | 5.0 | 0.61 (0.55–0.68) |

| [34] | Dartois-2 | 2015 | France | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 7331 | 42–72 | Postmenopausal Women in French E3N (E´ tude E´ pide´miologique aupre`s des femmes de laMutuelle Ge´ne´rale de l’E´ ducation Nationale (MGEN)) prospective cohort to investigate the cancer risk factors | High risk | 1993–1998 | 14.0 | 0.55 (0.50–0.60) |

| [39] | Hu | 2015 | China | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 42,908 | 35–69 | Women participated in the breast cancer screening in Zhejiang eastern coastal areas of China | General population | 2008–2014 | 5.0 | 0.59 (0.47–0.70) |

| [35] | Brentnall | 2015 | United Kingdom | Cohort | 2 | 10 | 50,628 | 47–73 | 15 screening areas in Greater Manchester, UK | General population | 2009–2014 | 3.2 | 0.54 (0.52–0.56) |

| [20] | Schonberg-1 | 2015 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 71,293 | 70.0 ± 7.0 | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | High risk | 2004–2009 | 5.0 | 0.57 (0.55–0.58) |

| [20] | Schonberg-2 | 2015 | America | Cohort | 2 | 5 | 79,611 | 71.0 ± 6.8 | Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), extensive study | High risk | 2005–2010 | 5.0 | 0.58 (0.56–0.59) |

| [46] | Rong | 2016 | China | Case–control | 1 | 5 | 816 | 48.9 | Breast cancer cases and controls in the Shenzhen Maternal and Child Health Care hospital | NA | 2011–2013 | NA | 0.69 (0.68–0.71) |

Note: Gail model type 1, original Gail model; Gail model type 2, modified Gail model for Caucasian-American; Gail model type 3, modified Gail model for Asian-American

AUC area under the area under the curve, CI confidence interval, NA not available

aCohort studies enrolled women with high risk for breast cancer (with higher average age (> 70 years), abnormal breast density, postmenopausal state, breast cancer relatives or high rate of delayed childbirth) were defined as “High risk”; cohort studies that did not accurately depict the characteristics of the participants were defined as “Not defined”. Case–control studies and cross-sectional studies were defined as not available

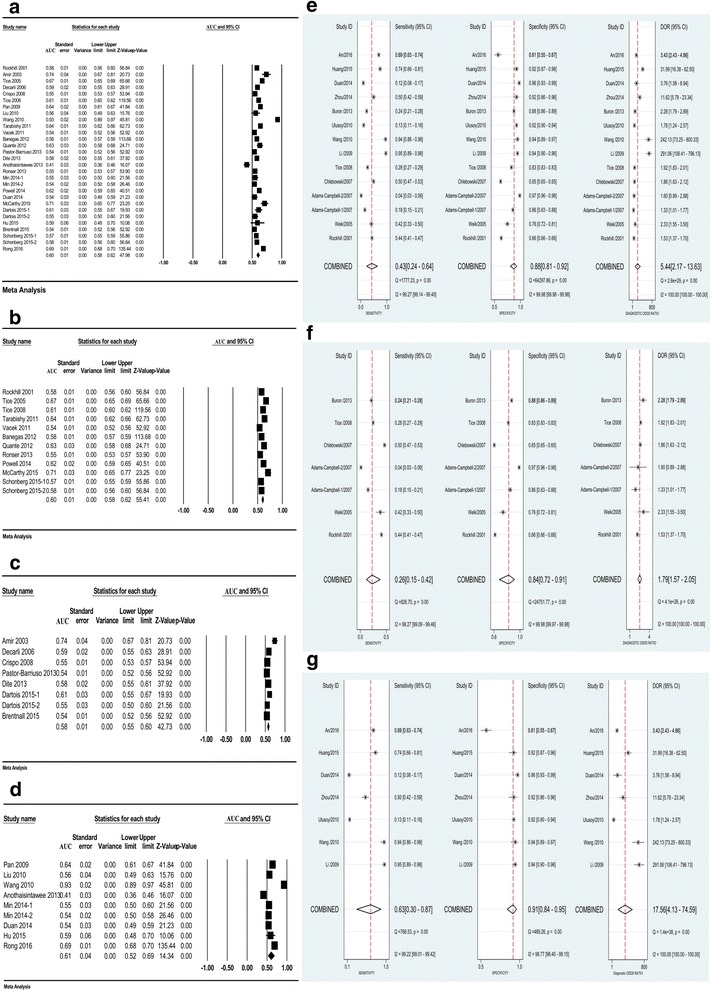

Fig. 3.

Pooled discrimination and diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model in total or stratified by geographic region. Pooled AUC/C-statistic of the Gail model in total (a) and studies from America (b), Europe (c) and Asia (d), respectively. Pooled sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) of the Gail model in total (e) and studies from America and Europe (f) and Asia (g), respectively. AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval

When stratified by geographic region, the pooled AUCs in American, European and Asian women were 0.60 (95% CI 0.58–0.62), 0.58 (95% CI 0.55–0.60) and 0.61 (95% CI 0.52–0.69), respectively, with no significant heterogeneities (p = 0.30) (Fig. 3b–d and see Additional file 10). Subgroup analysis also showed that the pooled AUC in studies with sample size ≥ 10,000 was lower (0.57 vs 0.64; p = 0.01). However, the combined AUC was not markedly changed when stratified by other factors (see Additional file 10). The funnel plot indicated no publication bias (Egger’s regression coefficient = −1.25; p = 0.54) (see Additional file 11A). According to the trim-and-fill method, eight studies had to be trimmed and the adjusted pooled AUC was 0.63 (95% CI 0.60–0.65) after trimming (see Additional file 11B). In addition, when stratified by geographic region, the funnel plot found significant publication bias across the studies in Europe (Egger’s regression coefficient = 4.45; p = 0.01) (see Additional file 12). After trimming, the adjusted AUC in European women was 0.59 (95% CI 0.56–0.62).

Results also showed the pooled AUC for Gail model 1 was 0.70 (95% CI 0.57–0.77), and when stratified by the geographic region the pooled AUCs for Gail model 1 in American and European women [22, 36] and Asian females [42, 44, 46] were 0.55 (95% CI 0.53–0.56) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.63–0.88), respectively (see Additional files 10 and 13). Additionally, the pooled AUC for Gail model 2 was 0.59 (95% CI 0.57–0.61), and when stratified by the geographic region and different versions of Gail model 2 the pooled AUCs for Caucasian-American Gail model 2 in American [15, 17–21, 23, 24, 27], Asian [39, 41, 43, 45] and European [29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 51] females were 0.61 (95% CI 0.59–0.63), 0.55 (95% CI 0.52–0.58) and 0.58 (95% CI 0.55–0.62), respectively (see Additional file 13). However, only one study clearly stated that they used Asian-American Gail model 2, and the AUC was reported to be 0.54 (95% CI 0.50–0.59) [41].

Diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model

Thirteen studies [11, 15, 25, 26, 31, 33, 37, 44, 45, 47–50] with 783,601 participants were included in this diagnostic meta-analysis (Table 3). The combined sensitivity, specificity and pooled DOR were 0.43 (95% CI 0.24–0.64), 0.88 (95% CI 0.81–0.92), and 5.44 (95% CI 2.17–13.63), respectively (Fig. 3e). Deeks’ funnel plot suggested that publication bias existed among the studies (p = 0.026) (see Additional file 14A).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies for estimating the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model

| Ref | Author | Publication year | Geographic background | Study design | Gail model version | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Study population | Time period | TP | FP | FN | TN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | Rockhill | 2001 | America | Cohort | 2 | 82,109 | 45–71 | Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | 1992–1997 | 596 | 27,457 | 758 | 53,298 |

| [25] | Weik | 2005 | America | Cross-sectional | 2 | 543 | 20–80 | Women who underwent a stereotactic or ultrasound-guided breast biopsy examination | 2001–2003 | 58 | 95 | 81 | 309 |

| [26] | Adams-Campbell-1 | 2007 | America | Nested case–control | 1 | 1450 | 21–69 | Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS) | 1995–2003 | 130 | 102 | 595 | 623 |

| [26] | Adams-Campbell-2 | 2007 | America | Nested case–control | 3 | 1450 | 21–69 | Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS) | 1995–2003 | 30 | 19 | 695 | 706 |

| [31] | Chlebowski | 2007 | America | Cohort | 2 | 64,568 | 63 | Predicted ER-positive breast cancer in Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study | 1993–2005 | 462 | 22,276 | 461 | 41,369 |

| [15] | Tice | 2008 | America | Cohort | 2 | 629,229 | 40–74 | National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) | Since1994 | 2442 | 103,852 | 6342 | 516,593 |

| [47] | Li | 2009 | China | Case–control | 2 | 420 | 40–75 | Bao’an Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Shenzhen | 2003–2008 | 98 | 20 | 5 | 297 |

| [44] | Wang | 2010 | China | Case–control | 1 | 228 | 56 | Breast cancer and controls in Shenzhou Hospital of Shenyang Medical College | 1998–2007 | 65 | 10 | 4 | 149 |

| [37] | Ulusoy | 2010 | Turkey | Case–control | 2 | 1290 | 49.49 | Breast cancer and controls in Ankara University School of Medicine | 2002–2008 | 87 | 51 | 563 | 589 |

| [33] | Buron | 2013 | Spain | Cohort | 2 | 2200 | 49–64 | Participants with a positive screening mammogram in “Parc de Salut Mar” breast cancer screening program | 1996–2010 | 24 | 449 | 28 | 1161 |

| [48] | Zhou | 2014 | China | Case–control | 1 | 280 | 48.62 | Breast cancer and controls in Huangpu District in Shanghai of China | 2010 | 72 | 11 | 71 | 126 |

| [45] | Duan | 2014 | China | Case–control | 2 | 400 | 52.58 | Breast cancer and controls in the First Affiliated Hospital of KunMing Medical University | 2007–2011 | 24 | 7 | 176 | 193 |

| [49] | Huang | 2015 | China | Case–control | 1 | 317 | 54.1 | Breast cancer and controls in Guangxi Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital | 2012–2014 | 116 | 13 | 41 | 147 |

| [50] | An | 2016 | China | Case–control | 2 | 567 | > 40 | Breast cancer and controls in China Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University | 2011–2015 | 207 | 105 | 93 | 162 |

Note: Gail model type 1, original Gail model; Gail model type 2, modified Gail model for Caucasian-American; Gail model type 3, modified Gail model for African-American

TP true positive, FP false positive, FN false negative, TN true negative, ER estrogen receptor

When stratified by geographic region, the pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR in American and European women were 0.26 (95% CI 0.15–0.42), 0.84 (95% CI 0.72–0.91) and 1.79 (95% CI 1.57–2.05), respectively (Fig. 3f) and Deeks’ funnel plot showed no publication bias (p = 0.50) (see Additional file 14B). With respect to Asian women, the pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR were 0.63 (95% CI 0.30–0.87), 0.91 (95% CI 0.84–0.95) and 17.56 (95% CI 4.13–74.59), respectively (Fig. 3g). However, publication bias persisted (p = 0.019) (see Additional file 14C).

When further stratified by different versions of the Gail model, the pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR of Gail model 1 were 0.63 (95% CI 0.27–0.89), 0.91 (95% CI 0.87–0.94) and 17.38 (95% CI 2.66–113.70), respectively, and the corresponding indexes of Gail model 2 were 0.35 (95% CI 0.17–0.59), 0.86 (95% CI 0.76–0.92) and 3.38 (95% CI 1.40–8.17), respectively (see Additional file 15). When subgrouped by different versions of Gail model 2, the pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR of the Caucasian-American Gail model for American and European women [11, 15, 25, 31, 33] were 0.36 (95% CI 0.27–0.45), 0.77 (95% CI 0.67–0.84) and 1.81 (95% CI 1.66–1.96), respectively, and for Asian females were 0.49 (95% CI 0.11–0.88), 0.90 (95% CI 0.76–0.96) and 8.80 (95% CI 1.19–64.81), respectively [37, 45, 47, 50] (see Additional file 16). However, only one study stated that they used the African-American Gail model and the sensitivity and specificity were reported to be 0.04 (95% CI 0.03–0.05) and 0.97 (95% CI 0.96–0.98), respectively [26]. Subgroup analysis also indicated that the pooled sensitivity with sample size < 1000 was higher than that in studies with ≥ 1000 samples, and the pooled specificity in studies with case–control design, sample size < 1000 and study quality < 8 points was higher than each of their counterparts (see Additional file 17).

Performance of the Gail model after excluding studies published in Chinese

When excluding studies retrieved in the WANFANG, VIP and CNKI databases, no effect was found on the calibration of Gail model 1. The E/O ratios of the Caucasian-American Gail model and the Asian-American Gail model for Asian women were reported as 2.46 (95% CI 2.10–2.88) and 1.82 (95% CI 1.68–2.04), respectively (see Additional file 18A).

The pooled AUC for Gail model 1 was 0.55 (95% CI 0.53–0.56). After excluding studies published in Chinese, only one study validated discrimination of Asian-American Gail model 2 and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 for Asian females and the AUCs were shown as 0.54 (95% CI 0.50–0.58) and 0.55 (95% CI 0.50–0.60), respectively [41] (see Additional file 18B).

For the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model, after excluding studies conducted in China, the pooled sensitivity, specificity and the DOR of the Gail model were 0.24 (95% CI 0.14–0.38), 0.85 (95% CI 0.75–0.92) and 1.79 (95% CI 1.58–2.03), respectively. When stratified by different versions of the Gail model, the sensitivity, specificity and the DOR of the Caucasian-American Gail model were 0.25 (95% CI 0.14–0.41), 0.85 (95% CI 0.72–0.93) and 1.89 (95% CI 1.68–2.13), respectively. Only one study remained to evaluate the performance of Gail model 1, and the sensitivity and specificity were reported as 0.15 (95% CI 0.18–0.21) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.83–0.88), respectively [26] (see Additional file 19).

Discussion

The current study comprehensively evaluated the calibration, discrimination and diagnostic accuracy of different versions of the Gail model. Gail model 1 and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 accurately predicted breast cancer risk for American and European women. However, the Caucasian-American and Asian-American Gail models overpredicted the risk for developing breast cancer about two times in Asian females. TSA showed that evidence in Asian women was sufficient; nonetheless, the results in American and European women need further verification. Moreover, the discrimination and the diagnostic accuracy of any versions of the Gail model were not satisfactory overall or stratified by geographic region.

The current study showed that both the Caucasian-American and the Asian-American Gail models overpredicted the risk for developing breast cancer in Asian women. To explain the results, firstly, the Gail model was constructed based on American white females, but the incidence of breast cancer in Asia (29.1/100,000) was much lower than that in American women (69.9/100,000) [1]. Accordingly, during a specific period, Asian women might not present with so many breast cancer incident cases as expected, leading to a higher E/O ratio. Secondly, the distributions of factors included in the Gail model were different between Asian and American women. Morabia and Costanza [79] conducted an international comparison on reproductive factors in 1998 and found age at first live birth in Asian women was older than that in American females, which may present a higher risk prediction in Asia according to the Gail model [3, 12]. Another potential explanation was the lack of regular breast cancer screening in Asian women. In America, conventional mammography examination would be conducted for women aged 45–74 years every 1 or 2 years [80, 81] and the Gail model was constructed based on women with annual screening [3, 12]. However, routine screening was seldom conducted in Asian women [82]; many of the breast cancer patients could not be detected and resulted in a lower number of observed breast cancer than actually existed, resulting in a higher E/O ratio.

Gail model 1 was designed for white women who were being screened annually [3]. The current version of Gail model 2 used Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) breast cancer rates for Asian-American women and the relative and attributable risks were derived from Asian-American females [8]. The Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool program specifically warns against the use of the Gail model in Asian women, where breast cancer rates are lower than those in Asian-American women [1]. Accordingly, the risk prediction of the Gail model should be explained with caution when applying it to Asian women and it is necessary to modify the Gail model based on the special risk factors and incidence of breast cancer in Asia, to improve its performance.

For the discrimination of the Gail model, results showed that the pooled AUC was moderately acceptable, while substantial heterogeneities exist between studies. Sample size could partly explain the phenomenon, and two studies with extreme value markedly affected the results. Anothaisintawee et al. [40] reported that the AUC of the Gail model was 0.41 with sample size > 1000, while the study conducted by Wang et al. [44] showed the AUC was 0.93 with < 1000 participants. Subgroup analysis showed no heterogeneities in sample size (≥ 1000 and < 1000) when these two datasets were excluded (0.62 vs 0.58; p = 0.07).

Previous meta-analyses also showed similar results that the Gail model had a satisfactory calibration and moderately acceptable discrimination [53–55]. Besides, the current study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model and the results showed that the sensitivity of the Gail model was poor and the results were even worse when focusing on the studies in American and European women. Accordingly, many of the breast cancer cases were misdiagnosed and this may partly explain the modest discrimination of the Gail model to some extent. Other risk factors for breast cancer such as mammographic density [83] and genetic factors [84] should be added to the Gail model in the future to provide a more accurate prediction of breast cancer. Nonetheless, few studies were combined to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model; more related studies are required to further confirm the results in the future.

Diagnostic meta-analysis also showed that the pooled specificity was higher in Asian women than that in American and European women, and studies with a case–control design, sample size < 1000 and study quality < 8 points presented a higher specificity than each of their counterparts. All studies in Asia were conducted using the hospital-based case–control design and the healthy controls were prone to have fewer risk factors than the cases. For example, biopsy is required for breast cancer cases, but is rarely used in healthy women in Asia; this may lead to lower prediction of risk in controls according to the Gail model and may increase the true negative rate and the specificity value. Moreover, most of the case–control studies were conducted with smaller sample sizes and lower study quality, and thus the difference in these subgroups may be partly explained by the distorted distribution of the case–control studies.

Additionally, Deeks’ funnel plot showed publication bias exists in Chinese studies, some studies with small sample size and lower DOR may not be published, and the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model may be overestimated to some extent. Sensitivity analysis showed that when excluding studies conducted in Chinese, the pooled specificity of the Gail model was not significantly altered but the pooled sensitivity and DOR were markedly decreased.

Limitations

The current study detected substantial heterogeneities across the studies for the three statistics that we summarized; these heterogeneities can be partially explained, but could not be markedly diminished by different geographic regions and various versions of the Gail model. Secondly, although many studies tried to evaluate the performance of different versions of the Gail model, they could not be included in this meta-analysis as they did not provide necessary indexes of the E/O ratio or the AUC with 95% CIs [85, 86]. This limits the power of this meta-analysis to evaluate the performance of different versions of the Gail model. Thirdly, most of the included studies did not clarify which version of Gail model 2 was utilized in their studies. In the current meta-analysis, the American and European studies who cited Constantino et al.’s paper [12] and the Asian studies which were published before the Asian-American Gail model was developed [8] were all deemed to be Caucasian-American Gail model 2. This may lead to misclassification to some extent and may partly affect the precision of the results. Finally, in order to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the Gail model in China, the WANFANG, VIP and CNKI databases were searched, which may partly overestimate the diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model, although it has no significant effect on the Gail model’s calibration and discrimination.

Conclusions

Although the original Gail model 1 and the Caucasian-American Gail model had a well-fitting calibration in American and European women, the Caucasian-American and Asian-American Gail models may overestimate the risk in Asian females about two times. Moreover, the discrimination and diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model were not satisfactory overall or stratified by geographic region and different versions of the Gail model. Accordingly, the Gail model was appropriate for predicting the incidence of breast cancer in American and European women, but not suitable for use in Asian women. Furthermore, this model cannot tell a woman whether she will or will not develop breast cancer precisely. Even so, it is still very valuable for women to have a well-calibrated risk assessment and select different prevention strategies that are suitable for their risk level.

Additional files

Shows sensitivity analysis (A), cumulative meta-analysis ranked by publication year (B) and sample size (C) of the calibration of the Gail model. (PDF 1593 kb)

Shows funnel plot of calibration of the Gail model (shows) and funnel plot adjusted by trim-and-fill method (B). (PDF 255 kb)

Shows subgroup analysis of calibration of the Gail model. (PDF 103 kb)

Shows funnel plot of calibration of the Gail model when stratified by geographic region in America (A), Europe (B) and Asia (C). (PDF 305 kb)

Shows forest plot of calibration of the Asian-American version of Gail model 2 in Asian females and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 in American, Asian and European women. (PDF 663 kb)

Shows forest plot (A), sensitivity analysis (B) and cumulative analysis ranked by publication year (C) and sample size (D) of calibration of the Gail model after excluding studies conducted in Asian women. (PDF 1202 kb)

Shows pooled E/O ratio for Gail model 1 and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 after excluding studies conducted in Asian women. (PDF 582 kb)

Shows subgroup analysis of calibration of the Gail model after excluding studies conducted in Asian women. (PDF 106 kb)

Shows sensitivity analysis (A), cumulative meta-analysis ranked by publication year (B) and sample size (C) of discrimination of the Gail model. (PDF 1321 kb)

Shows subgroup analysis of discrimination of the Gail model. (PDF 104 kb)

Shows funnel plot of discrimination of the Gail model (A) and funnel plot adjusted by trim-and-fill method (B). (PDF 226 kb)

Shows funnel plot of discrimination of the Gail model when stratified by geographic region in America (A), Europe and others (B) and Asia (C). (PDF 278 kb)

Shows pooled AUC for Caucasian-American Gail model 2 in American, Asian and European women and Gail model 1 in American and European women and Asian females. (PDF 686 kb)

Shows Deeks’ funnel plot of diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis (A) and funnel plot of stratified analysis in America and Europe (B) and Asia (C). (PDF 294 kb)

Shows pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR of Gail model 1 (A) and Gail model 2 (B). (PDF 994 kb)

Shows pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR of the Caucasian-American Gail model in American and European women (A) and Asian females (B). (PDF 828 kb)

Shows subgroup analysis of diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model. (PDF 376 kb)

Shows calibration (A) and discrimination (B) of different versions of the Gail model after excluding studies published in Chinese. (PDF 531 kb)

Shows pooled sensitivity, specificity and DOR of Gail model 1 and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 after excluding studies published in Chinese. (PDF 888 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Hong Zheng, Xiangchun Li, Qiang Zhang, Ping Cui, Hao Chen, Huijun Yang, and Qinghua Wang who provided suggestions for editing this manuscript and they thank Juatina Ucheojor Onwuka for the language polishing work.

Funding

This work was funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (2017 M621091), The Doctor Start-up Grant of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (B1612), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81473039 and 81502476), Chinese National Key Scientific and Technological Project (Grants 2014BAI09B09), The Science & Technology Development Fund of Tianjin Education Commission for Higher Education (No. 20140141), and in part by the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University in China (IRT_14R40) and Tianjin Municipal Key Health Research Program grant 15KG143.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study included in this published article and its additional files can be found online (http://pan.baidu.com/s/1jIkWTwU).

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BCRAT

Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool

- CI

Confidence interval

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- C-statistic

Concordance statistic

- DOR

Diagnostic odds ratio

- E/O

Expected-to-observed ratio

- FN

False negative

- FP

False positive

- MeSH

Medical subject headings

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- QUADAS

Quality Assessment Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

- RIS

Required information size

- SEER

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results

- TN

True negative

- TP

True positive

- TSA

Trial sequential analysis

Authors’ contributions

XW designed the study, conducted the literature search, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. YH conducted the literature search and revised the manuscript. LL and HD extracted the data, conducted the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. FS and KC supervised the study procedure and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The tables and figures in the paper are original for this article and the authors have permission to use them.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13058-018-0947-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xin Wang, Email: wangxinmarine@126.com.

Yubei Huang, Email: yubei_huang@163.com.

Lian Li, Email: lianl_tjmuch@naver.com.

Hongji Dai, Email: daihongji@126.com.

Fengju Song, Email: songfengju@163.com.

Kexin Chen, Email: chenkexin@tjmuch.com.

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/summary_table_pop_sel.aspx. Accessed 31 Jun 2017.

- 2.Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool. National Cancer Institute. 2011. https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/. Accessed 13 Aug 2017.

- 3.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson SJ, Ahnn S, Duff K. NSABP Breast Cancer Prevention Trial risk assessment program, version 2. NSABP Biostatistical Center Technical Report. 1992.

- 5.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–2741. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gail MHCJ, Pee D, Bondy M, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in African American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1782–1792. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuno RK, Costantino JP, Ziegler RG, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in Asian and Pacific Islander American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:951–961. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bondy ML, Lustbader ED, Halabi S, et al. Validation of a breast cancer risk assessment model in women with a positive family history. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:620–625. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.8.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Hunter D, Hertzmark E. Validation of the Gail et al. model for predicting individual breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:600–607. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.8.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockhill B, Spiegelman D, Byrne C, et al. Validation of the Gail et al. model of breast cancer risk prediction and implications for chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:358–366. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantino JP, Gail MH, Pee D, et al. Validation studies for models projecting the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1541–1548. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.18.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernatsky S, Clarke A, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. Hormonal exposures and breast cancer in a sample of women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology. 2004;43:1178–1181. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson JE, Sellers TA, Iturria SJ, Hartmann LC. Bilateral oophorectomy and breast cancer risk reduction among women with a family history. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, et al. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:337–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schonfeld SJ, Pee D, Greenlee RT, et al. Effect of changing breast cancer incidence rates on the calibration of the Gail model. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2411–2417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarabishy Y, Hartmann LC, Frost MH, et al. Performance of the Gail model in individual women with benign breast disease. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. 2011;29(Suppl 15):1525. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell M, Jamshidian F, Cheyne K, Nititham J, Prebil LA, Ereman R. Assessing breast cancer risk models in Marin County, a population with high rates of delayed childbirth. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy AM, Keller B, Kontos D, et al. The use of the Gail model, body mass index and SNPs to predict breast cancer among women with abnormal (BI-RADS 4) mammograms. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:1. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schonberg MA, Li VW, Eliassen AH, et al. Performance of the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool among women age 75 years and older. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(3). 10.1093/jnci/djv348. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Performance+of+the+Breast+Cancer+Risk+Assessment+Tool+among+women+age+75+years+and+older. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Ziv E, Kerlikowske K. Mammographic breast density and the Gail model for breast cancer risk prediction in a screening population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94:115–122. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-5152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vacek PM, Skelly JM, Geller BM. Breast cancer risk assessment in women aged 70 and older. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quante AS, Whittemore AS, Shriver T, et al. Breast cancer risk assessment across the risk continuum: genetic and nongenetic risk factors contributing to differential model performance. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R144. doi: 10.1186/bcr3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, et al. Validation of Rosner-Colditz breast cancer incidence model using an independent data set, the California Teachers Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:187–202. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2719-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weik JL, Lum SS, Esquivel PA, et al. The Gail model predicts breast cancer in women with suspicious radiographic lesions. Am J Surg. 2005;190:526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams-Campbell LL, Makambi KH, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Diagnostic accuracy of the Gail model in the Black Women's Health Study. Breast J. 2007;13:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banegas MP, Gail MH, LaCroix A, et al. Evaluating breast cancer risk projections for Hispanic women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1900-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyle P, Mezzetti M, La Vecchia C, et al. Contribution of three components to individual cancer risk predicting breast cancer risk in Italy. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:183–191. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000130014.83901.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decarli A, Calza S, Masala G, Specchia C, Palli D, Gail MH. Gail model for prediction of absolute risk of invasive breast cancer: independent evaluation in the Florence-European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1686–1693. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amir E, Evans DG, Shenton A, et al. Evaluation of breast cancer risk assessment packages in the family history evaluation and screening programme. J Med Genet. 2003;40:807–814. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.11.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Lane DS, et al. Predicting risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women by hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastor-Barriuso R, Ascunce N, Ederra M, et al. Recalibration of the Gail model for predicting invasive breast cancer risk in Spanish women: a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2428-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buron A, Vernet M, Roman M, et al. Can the Gail model increase the predictive value of a positive mammogram in a European population screening setting? Results from a Spanish cohort. Breast. 2013;22:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dartois L, Gauthier E, Heitzmann J, et al. A comparison between different prediction models for invasive breast cancer occurrence in the French E3N cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:415–426. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brentnall AR, Harkness EF, Astley SM, et al. Mammographic density adds accuracy to both the Tyrer-Cuzick and Gail breast cancer risk models in a prospective UK screening cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:147. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0653-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crispo A, D'Aiuto G, De Marco M, et al. Gail model risk factors: impact of adding an extended family history for breast cancer. Breast J. 2008;14:221–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulusoy C, Kepenekci I, Kose K, Aydintug S, Cam R. Applicability of the Gail model for breast cancer risk assessment in Turkish female population and evaluation of breastfeeding as a risk factor. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:419–424. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chay WY, Ong WS, Tan PH, et al. Validation of the Gail model for predicting individual breast cancer risk in a prospective nationwide study of 28,104 Singapore women. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R19. doi: 10.1186/bcr3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu JY. Research on the applicability of Gail model in the assessment of breast cancer risk in Zhejiang eastern coastal women. Zhejiang University Medical College; 2015. http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201502&filename=1015614713.nh&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldRa1Fhb09jSnZpZ0poVENnSEttRElqTVFNQXBUczBDVT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4ggI8Fm4gTkoUKaID8j8gFw!!&v=MjU4ODFYMUx1eFlTN0RoMVQzcVRyV00xRnJDVVJMS2ZaT1ptRnl2a1VyM09WRjI2RzdXNUd0Yk5ySkViUElSOGU=.

- 40.Anothaisintawee T, Thakkinstian A, Wiratkapun C, et al. Developing and validating risk prediction model for screening breast cancer in Thai women. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(Suppl 1):96–97. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Min JW, Chang MC, Lee HK, et al. Validation of risk assessment models for predicting the incidence of breast cancer in Korean women. J Breast Cancer. 2014;17:226–235. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2014.17.3.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan XP, Jin X, Ding H, et al. Preliminary study on risk evaluation model of breast cancer in Beijing and Guangdong. Matern Child Health Care of China. 2009;11:1469–1471. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu LY. A pilot study on risk factors and risk assessment score screening model for high-risk population of breast cancer. Shandong University; 2010. http://g.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y1793588.

- 44.Wang Y, Xu L, Shen CJ, et al. Clinical application of Gail model in the assessment of breast cancer risk. Int J Pathol Clin Med. 2010;6:473–475. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duan XK, Luo ZY, Chen L, et al. The application of the Gail breast cancer prediction model in Chinese women. Matern Child Health Care of China. 2014;28:4667–4669. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rong L, Li H, Wang EL. To establish the breast cancer risk prediction model for women in Shenzhen in China. Matern Child Health Care of China. 2016;3:470–473. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li JM, Wang W, Li SY. Elementary study on application of Gail model breast cancer risk assessment tool. China Modern Med. 2009;14:40–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou JJ, Wang YJ, Gao SN, et al. Application of Gail model for assessment on breast cancer risk. Shanghai J Prev Med. 2014;5:236–239. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang JH. Application of the Gail prediction model for breast cancer in the community. Chin Foreign Med Res. 2015;35:151–152. [Google Scholar]

- 50.An LY, Zhang KZ, Zhang YL, et al. To explore the application of the Gail and Cuzick-Tyrer breast cancer prediction model. Matern Child Health Care of China. 2016;5:945–946. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dite GS, Mahmoodi M, Bickerstaffe A, et al. Using SNP genotypes to improve the discrimination of a simple breast cancer risk prediction model. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:887–896. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2610-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacInnis R, Dite G, Bickerstaffe A, et al. Validation study of risk prediction models for female relatives of Australian women with breast cancer. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2012;10(Suppl 2). https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L70928745.

- 53.Anothaisintawee T, Teerawattananon Y, Wiratkapun C, et al. Risk prediction models of breast cancer: a systematic review of model performances. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1853-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meads C, Ahmed I, Riley RD. A systematic review of breast cancer incidence risk prediction models with meta-analysis of their performance. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:365–377. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1818-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson HD, Pappas M, Zakher B, et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:255–266. doi: 10.7326/M13-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Estimating required information size by quantifying diversity in random-effects model meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.WANFANG database. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/. Accessed 31 Jul 2016.

- 60.VIP database. http://www.cqvip.com/. Accessed 31 Jul 2016.

- 61.China National Knowledge Infrastructure database. http://www.cnki.net/. Accessed 31 Jul 2016.

- 62.Pankratz VS, Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, et al. Assessment of the accuracy of the Gail model in women with atypical hyperplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5374–5379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McKian KP, Reynolds CA, Visscher DW, et al. Novel breast tissue feature strongly associated with risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5893–5898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mealiffe ME, Stokowski RP, Rhees BK, et al. Assessment of clinical validity of a breast cancer risk model combining genetic and clinical information. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1618–1627. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dite GS, MacInnis RJ, Bickerstaffe A, et al. Breast cancer risk prediction using clinical models and 77 independent risk-associated SNPs for women aged under 50 years: Australian Breast Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:359–365. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pankratz VS, Degnim AC, Frank RD, et al. Model for individualized prediction of breast cancer risk after a benign breast biopsy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:923–929. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Allman R, Dite GS, Hopper JL, et al. SNPs and breast cancer risk prediction for African American and Hispanic women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154:583–589. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3641-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thakkinstian A, McElduff P, D’Este C, et al. A method for meta-analysis of molecular association studies. Stat Med. 2005;24:1291–1306. doi: 10.1002/sim.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mullen B, Muellerleile P, Bryant B. Cumulative meta-analysis: a consideration of indicators of sufficiency and stability. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;27:1450–1462. doi: 10.1177/01461672012711006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Begg CB. Publication bias: a problem in interpreting medical data. JR Statist Soc A. 1988;151:419–463. doi: 10.2307/2982993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:882–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Brok J, et al. User manual for trial sequential analysis (TSA) Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research; 2011. pp. 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morabia A, Costanza MC. International variability in ages at menarche, first live birth, and menopause. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:1195–1205. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279–296. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314:1599–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang Y, Dai H, Song F, et al. Preliminary effectiveness of breast cancer screening among 1.22 million Chinese females and different cancer patterns between urban and rural women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39459. doi: 10.1038/srep39459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Antoniou AC, Wang X, Fredericksen ZS, et al. A locus on 19p13 modifies risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers and is associated with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer in the general population. Nat Genet. 2010;42:885–892. doi: 10.1038/ng.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Abu-Rustum NR, Herbolsheimer H. Breast cancer risk assessment in indigent women at a public hospital. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:287–290. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bondy ML, Newman LA. Breast cancer risk assessment models: applicability to African-American women. Cancer. 2003;97:230–235. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Shows sensitivity analysis (A), cumulative meta-analysis ranked by publication year (B) and sample size (C) of the calibration of the Gail model. (PDF 1593 kb)

Shows funnel plot of calibration of the Gail model (shows) and funnel plot adjusted by trim-and-fill method (B). (PDF 255 kb)

Shows subgroup analysis of calibration of the Gail model. (PDF 103 kb)

Shows funnel plot of calibration of the Gail model when stratified by geographic region in America (A), Europe (B) and Asia (C). (PDF 305 kb)

Shows forest plot of calibration of the Asian-American version of Gail model 2 in Asian females and Caucasian-American Gail model 2 in American, Asian and European women. (PDF 663 kb)